Stiff Upper Lip: A Terribly British History

- Thread starter unmerged(62170)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ah, the French and Russians are being annoying again... don't they ever stop causing problems? Especially the French with England.

It appears that the Great Game is heating up. Antagonising the Russians in Asia might have consequences in Europe...

Jape: Aye...

RGB: They'll pay, I assure you

stnylan: Alaska looks tempting!

Judas Maccabeus: No, such is the great marriage of loathing the two great nations of Western Europe share

Ksim3000: Damn straight, never trust a Yank as a far as you can throw 'em (unitended obese jokes in there somewhere o )

o )

ComradeOm: Tread softly and carry a big stick my boy!

RGB: They'll pay, I assure you

stnylan: Alaska looks tempting!

Judas Maccabeus: No, such is the great marriage of loathing the two great nations of Western Europe share

Ksim3000: Damn straight, never trust a Yank as a far as you can throw 'em (unitended obese jokes in there somewhere

ComradeOm: Tread softly and carry a big stick my boy!

Funerals and Ner'do Wells

.jpg)

2.

On January 1st 1837, King William IV, despite his advanced age and poor health stood before an excited Portsmouth crowd to christen the HMS Acheron, living up to his moniker as the ‘Sailor-King’. Alongside the frail monarch and a motley collection of naval officers and civil servants, journalists from around the world were gathered, for the Acheron was no ordinary vessel. It was the first in a new class of steam-powered ‘paddle-frigates’, designed as commerce raiders and fast-attack ships. The top rung of the Admiralty, the Naval Lords, most of them having served in the great decisive battles of Trafalgar and Copenhagen, scoffed at the idea of the Royal Navy stooping to such French tactics as privateering. They also, on an aesthetic level, irked at the thought of the graceful ship-of-line being replaced by dwarven, glorified furnaces, sputtering steam and smoke, and causing chaos on the ‘field’ of battle.

However the progressive ideas of famed war hero Sir Charles Napier, along with his recent experiences in the Portuguese Civil War and close connections with Lord Palmerston, meant such innovations could hardly be ignored. They were further reinforced by the King’s own support, who despite his great dislike of the eccentric Napier, agreed with him on technical terms. The paddle-frigate was an extremely fast and resilient design for the period; although unable to produce the firepower of a Man-o-War, it could easily outmanoeuvre the wooden giants as well as receive far more punishment, due to the iron plating of its hull. And so, on a frosty New Years Day, HMS Acheron chugged out into the English Channel, the first of over several dozen of its kind that would be produced in the next decade to ensure Britannia still ruled the waves.

Steam power was increasing on land as well in the early months of 1837. The young railway companies, such as Great Western were sprawling ever further across the country, in time with growth of the new industrial towns and cities. Even in supposedly rural Ireland, the newly fashioned Ulster Railway Company was inching its way down the eastern coast, from Londonderry to Dublin, via Belfast. Aided by the free trade policies of the Whigs, the Emerald Isle’s former role as a mere breadbasket for the Empire was slowly being overshadowed by its newfound industrial output. Although the growth was concentrated in the Protestant north, with Ulster’s numerous textile and furniture factories employing tens of thousands, Dublin and even Cork produced steel was being exported around the world by the mid-1840’s. Similarly the coal industry in South Wales was beginning to take off, as was Scottish shipbuilding on the Firth of Forth, where many of the world’s new steamers would be built for decades to come. Even in far away South Africa, factories were starting to form in the more urban areas around Cape Town, along with the first railway on the Dark Continent, albeit only a half mile long connecting the coastal port to Cape Town’s small industrial area.

An early locomotive

The relative calm of the year (perhaps punctuated somewhat by the continuing civil war in Spain and an aggressive Persia skirmishing with Afghan warlords) suddenly came to an end on June 20th, when King William IV died of a cardiac arrest. As the nation mourned, HM’s Government dealt with the fallout. Lacking legitimate issue (though 8 bastards!), the crown was to be passed to his young niece, Princess Victoria of Kent aged just 19. Although matters such as regency or rival pretenders were of no importance, there was Hanover to contend with. William IV had issued his second Kingdom a liberal constitution, but he had retained the ancient Salic law, which barred females from the throne (his inaction on the issue was possibly intended to cut Westminster and Royal Family out of direct involvement in the ever complicated field of German politics). As such the Hanoverian throne was passed to William’s reactionary younger brother, Ernest Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland. His abolition of the liberal constitution would be a major step in future political unrest in Germany, but that is a tale for another time…

Although the new youthful Queen was welcome by many both home and abroad, a symbol of the glorious new age that Britain would lead the world into, all was not peaceful in the Empire. In British America, or accurately in the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, unrest was brewing. The oligarchic structure of rule in the colonies, dominated by business magnates and British-born gentry (known as the Family Compact in English-dominated Upper Canada, and the Château Clique amongst the Quebecois of Lower Canada) rankled greatly with the native working-class and intelligentsia. Inspired by the Great Reform Act, and to a lesser extent Catholic Emancipation amongst the Francophone population, a strong reformist movement developed, determined to democratise British America. However the unresponsive nature of the supposedly liberal Whig government eventually led to radical elements taking violent action.

Queen Victoria 1837

Led by Louis-Joseph Papineau, the paramilitary Society of the Brothers of Liberty rose in rebellion in November, quickly seizing much of the Lower Canadian countryside. Local militias were slow to react, leading to the republican William Mackenzie attempting to emulate Papineau’s actions in Upper Canada in December. However the garrison in nearby York (later Toronto) swiftly crushed the Anglo rebellion. Public support for the rebels quickly rose in the United States, the prize of the “14th Colony” inspiring pan-American fervour. However, President Van Buren was hardly keen to the idea of fighting the old Empire. Indeed, an attempt by a large force of American filibusters, volunteers hoping to unite Canada with Washington by force, to cross the border into Lower Canada was swiftly stopped in upstate New York by the US Army. However the rebellions put down by January 1838, and Lord Durham sent to investigate the obviously flawed system ruling over the North American colonies.

.jpg)

2.

On January 1st 1837, King William IV, despite his advanced age and poor health stood before an excited Portsmouth crowd to christen the HMS Acheron, living up to his moniker as the ‘Sailor-King’. Alongside the frail monarch and a motley collection of naval officers and civil servants, journalists from around the world were gathered, for the Acheron was no ordinary vessel. It was the first in a new class of steam-powered ‘paddle-frigates’, designed as commerce raiders and fast-attack ships. The top rung of the Admiralty, the Naval Lords, most of them having served in the great decisive battles of Trafalgar and Copenhagen, scoffed at the idea of the Royal Navy stooping to such French tactics as privateering. They also, on an aesthetic level, irked at the thought of the graceful ship-of-line being replaced by dwarven, glorified furnaces, sputtering steam and smoke, and causing chaos on the ‘field’ of battle.

However the progressive ideas of famed war hero Sir Charles Napier, along with his recent experiences in the Portuguese Civil War and close connections with Lord Palmerston, meant such innovations could hardly be ignored. They were further reinforced by the King’s own support, who despite his great dislike of the eccentric Napier, agreed with him on technical terms. The paddle-frigate was an extremely fast and resilient design for the period; although unable to produce the firepower of a Man-o-War, it could easily outmanoeuvre the wooden giants as well as receive far more punishment, due to the iron plating of its hull. And so, on a frosty New Years Day, HMS Acheron chugged out into the English Channel, the first of over several dozen of its kind that would be produced in the next decade to ensure Britannia still ruled the waves.

Steam power was increasing on land as well in the early months of 1837. The young railway companies, such as Great Western were sprawling ever further across the country, in time with growth of the new industrial towns and cities. Even in supposedly rural Ireland, the newly fashioned Ulster Railway Company was inching its way down the eastern coast, from Londonderry to Dublin, via Belfast. Aided by the free trade policies of the Whigs, the Emerald Isle’s former role as a mere breadbasket for the Empire was slowly being overshadowed by its newfound industrial output. Although the growth was concentrated in the Protestant north, with Ulster’s numerous textile and furniture factories employing tens of thousands, Dublin and even Cork produced steel was being exported around the world by the mid-1840’s. Similarly the coal industry in South Wales was beginning to take off, as was Scottish shipbuilding on the Firth of Forth, where many of the world’s new steamers would be built for decades to come. Even in far away South Africa, factories were starting to form in the more urban areas around Cape Town, along with the first railway on the Dark Continent, albeit only a half mile long connecting the coastal port to Cape Town’s small industrial area.

An early locomotive

The relative calm of the year (perhaps punctuated somewhat by the continuing civil war in Spain and an aggressive Persia skirmishing with Afghan warlords) suddenly came to an end on June 20th, when King William IV died of a cardiac arrest. As the nation mourned, HM’s Government dealt with the fallout. Lacking legitimate issue (though 8 bastards!), the crown was to be passed to his young niece, Princess Victoria of Kent aged just 19. Although matters such as regency or rival pretenders were of no importance, there was Hanover to contend with. William IV had issued his second Kingdom a liberal constitution, but he had retained the ancient Salic law, which barred females from the throne (his inaction on the issue was possibly intended to cut Westminster and Royal Family out of direct involvement in the ever complicated field of German politics). As such the Hanoverian throne was passed to William’s reactionary younger brother, Ernest Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland. His abolition of the liberal constitution would be a major step in future political unrest in Germany, but that is a tale for another time…

Although the new youthful Queen was welcome by many both home and abroad, a symbol of the glorious new age that Britain would lead the world into, all was not peaceful in the Empire. In British America, or accurately in the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, unrest was brewing. The oligarchic structure of rule in the colonies, dominated by business magnates and British-born gentry (known as the Family Compact in English-dominated Upper Canada, and the Château Clique amongst the Quebecois of Lower Canada) rankled greatly with the native working-class and intelligentsia. Inspired by the Great Reform Act, and to a lesser extent Catholic Emancipation amongst the Francophone population, a strong reformist movement developed, determined to democratise British America. However the unresponsive nature of the supposedly liberal Whig government eventually led to radical elements taking violent action.

Queen Victoria 1837

Led by Louis-Joseph Papineau, the paramilitary Society of the Brothers of Liberty rose in rebellion in November, quickly seizing much of the Lower Canadian countryside. Local militias were slow to react, leading to the republican William Mackenzie attempting to emulate Papineau’s actions in Upper Canada in December. However the garrison in nearby York (later Toronto) swiftly crushed the Anglo rebellion. Public support for the rebels quickly rose in the United States, the prize of the “14th Colony” inspiring pan-American fervour. However, President Van Buren was hardly keen to the idea of fighting the old Empire. Indeed, an attempt by a large force of American filibusters, volunteers hoping to unite Canada with Washington by force, to cross the border into Lower Canada was swiftly stopped in upstate New York by the US Army. However the rebellions put down by January 1838, and Lord Durham sent to investigate the obviously flawed system ruling over the North American colonies.

Last edited:

Its trivial of course but I can't help but wonder as to the impact of the spread of industrialisation in Ireland. If the rest of the island did match Ulster in terms of factories then it would no doubt have repercussions for the Rent Wars, rise of organised labour, partition, and, most importantly, the Great Famine. Naturally most of this is completely tangential to your, very well written, story

I always prefer a united empire but good luck whichever way you go

And maybe an update?

And maybe an update?

I like how you have described the era. It is true, times were changing and I am sure that today with people not liking "change" was very much the same back then.

Anyway, keep it up!

Anyway, keep it up!

Jape: Aye it does but not always smoothly...

stnylan: Very apt

ComradeOm: Hardly trivial, Ireland is crucial in the history of the British Empire. Your quite right though, an industrial Eire will alter its history greatly. We shall see how things pan out there.

Jalex: In game terms its useful (Ai Australia is hardly a prize winning ally during the Great War o ) but we'll see, I'm not entirely sure myself.

o ) but we'll see, I'm not entirely sure myself.

Ksim3000: Ah why thank you

stnylan: Very apt

ComradeOm: Hardly trivial, Ireland is crucial in the history of the British Empire. Your quite right though, an industrial Eire will alter its history greatly. We shall see how things pan out there.

Jalex: In game terms its useful (Ai Australia is hardly a prize winning ally during the Great War

Ksim3000: Ah why thank you

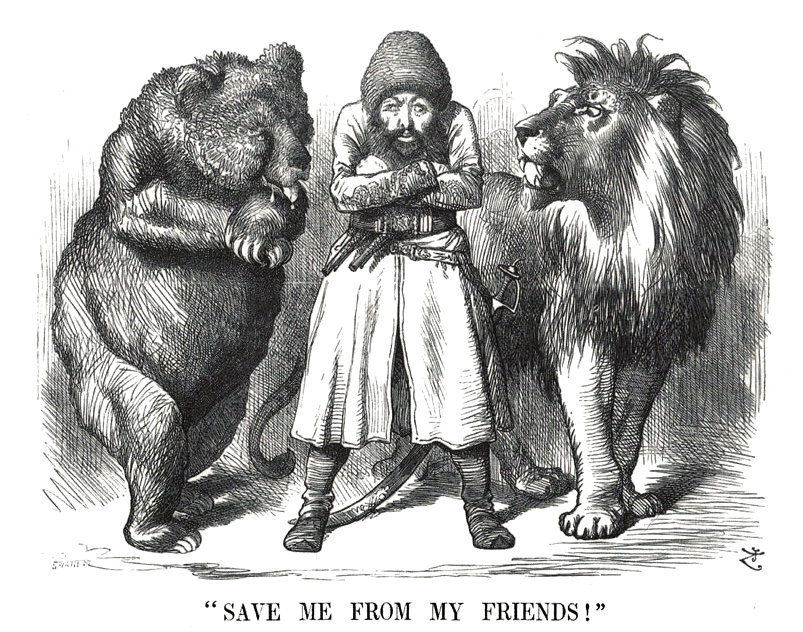

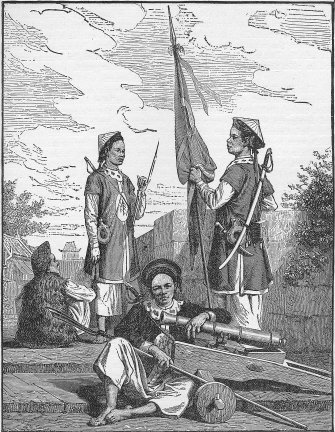

Save Me From My Friends

3.

Once more the situation in the Central Asia was beginning to destabilise in 1838. In the Khanate of Khiva, the northernmost of the nations of ‘Turkestan’, Tsar Nicholas I was pushing for war. He saw the British failures in the region two years prior as their inability and reluctance to project their power. However he was also quite aware that the vast native armies of the British East India Company were far better stationed to act in the area. As such he did not wish to appear overtly jingoistic, indeed he was quite willing to extend Russian influence south peacefully via diplomacy and bribe; but the proud warlords would never allow such a logical evolution. Instead he had intended to provoke the ‘savage Turkmen’, to smother them until they could take no more. To this effect, Khiva had been slowly inundated over the course of many months, with advisors and merchants from St. Petersburg, as well as Tehran. The Khan naturally, if cautiously, welcomed the foreigners who were willing to help modernise and strengthen his nation. However before long, demands began to arrive via the Russian consulate. The Tsar wished for payment for his services to Khiva, for the right to station troops, and even for the feudal right of vassalage. And so in early 1838, Turkic warriors rounded up Russian and Persian subjects, and with great bluster the Khan demanded the Tsar and Shah to retreat from Khiva and drop all demands. Nicholas must have rubbed his hands with glee. Soon over 30,000 Cossacks were marching towards the frontier to rescue the hostages from the clutches of the vile barbarian.

The Foreign and Colonial Offices were alive with activity, and Lord Palmerston barely slept for a week. Khiva was a domino, the first in a chain that could swiftly see the Russians looking into Afghanistan, or even India. If Britain didn’t act now, there would be little they could later save military action. However Lord Melbourne remained adamant that alternative routes be taken, scared of the corrupt organisation of the East India Company as much as Nicholas I. Much to the collective groan of the British camp, he called on another ‘goodwill mission’ in the region, to attempt negotiations with the Khan. Westminster would be attempting to rescue Russian and Persian agents. As swiftly as possible an expedition set out at speed to the depths of Central Asia. Arriving in late February, the party leader, Lt. Colonel Shakespeare, came bearing gifts of gold and spices, under the guise of a visit to encourage Khiva’s abolition of slavery. In the mere space of several hours, Shakespeare left once, having accomplished his mission. The Hostages were soon released, and Tsar Nicholas glumly called off his invasion. For now.

Over in North America, diplomacy was of a far more civilised affair, though not necessarily any more pleasant. The bankrupt Republic of Texas sought to better relations with Britain and France. In London in June, the Texan representative asked for official recognition of the young state, and a handsome loan to ease reconstruction following the bloody war for independence. Barring the financial implications, the Texans hoped that strong relations with the European Powers would discourage a Mexican revanche. Indeed, their southern neighbour had hardly forgotten the nation of rebellious gringos, particularly as they supported further insurrection in the Yucatan peninsula. However London and Mexico City were relatively close already, and there was strong resistance within the Cabinet and Parliament towards dealing with the Texans. Thomas Rice, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, in particular opposed such a move, fearful of losing influence and trade with Mexico. Radicals in the Commons too argued against even receiving a Texan delegation, on the grounds of their unapologetic stance towards slavery.

Vice-President Lamar of the Republic of Texas

Regardless, Lord Palmerston’s ever-growing influence over Lord Melbourne, and by extension the entire Whig political faction, won through. He saw the poor Anglo nation as a pliable pawn, far more so than Santa Anna’s mercurial Mexico. It was an open secret that despite warm relations between Britain and the United States, it was a long-term Foreign Office goal to deny Washington its ‘Manifest Destiny’. A vast American nation bordering both the Atlantic and Pacific would be an economic and trading powerhouse; a great threat to Westminster’s influence on the continent and further a field. Here Texas and to a lesser extent the rebellious Mexican province of Alta California fitted quite neatly. In Texas the pro-American president, Sam Houston was stepping down and his Vice-President and bitter rival Mirabeau Lamar looked set to win the coming election. A dreadful bigot and jingoist, Lamar led pro-independence supporters and sort to see Texas rival the U.S. Melbourne saw him as someone business could be done with and readily agreed not only to issue loans but secretly bankroll Lamar’s presidential campaign, a miniscule expense in reality but one that quickly endeared him to his new British friends.

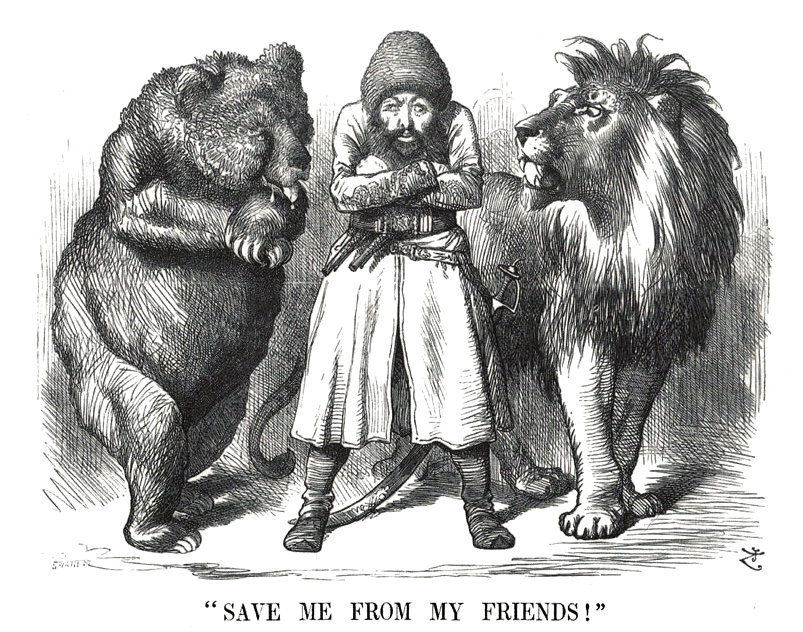

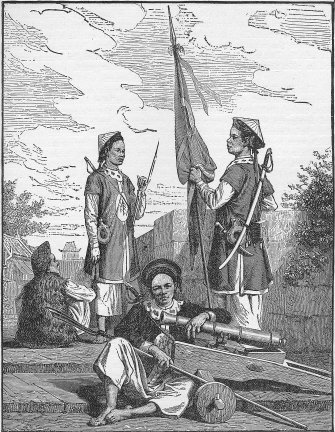

Attentions returned to Asia in 1839 as tensions with the Chinese Empire mounted. In March the crown colony of Ceylon raised three regiments of Ceylonese Hussars in order give Britain an offensive force in the region. Similarly a flotilla consisting of four Men-o-War, six Frigates and the newly commissioned Steam-Frigate HMS Volcano set sail for Singapore. Mounting pressure was being put on the East India Company’s operation in Canton regarding its imports of opium. Despite harsh punishments for addicts and traders of the drug, it soon spread across the Middle Kingdom. In turn, the Chinese authorities in Canton, the main port open to Western imports, began to attack the source, arresting and detaining British subjects. Lord Melbourne refused to crack down on the East India Company’s operation, sighting their “autonomy and independence to act as a commercial corporation, they alone will decide their actions”. However this affected the situation little. Finally on July 8th, Chinese soldiers battled British smugglers outside of Canton. Europeans in the city soon came under attack and word was quickly sent to Ceylon and London. On hearing of the events Melbourne and Parliament unanimously called for a declaration of war.

3.

Once more the situation in the Central Asia was beginning to destabilise in 1838. In the Khanate of Khiva, the northernmost of the nations of ‘Turkestan’, Tsar Nicholas I was pushing for war. He saw the British failures in the region two years prior as their inability and reluctance to project their power. However he was also quite aware that the vast native armies of the British East India Company were far better stationed to act in the area. As such he did not wish to appear overtly jingoistic, indeed he was quite willing to extend Russian influence south peacefully via diplomacy and bribe; but the proud warlords would never allow such a logical evolution. Instead he had intended to provoke the ‘savage Turkmen’, to smother them until they could take no more. To this effect, Khiva had been slowly inundated over the course of many months, with advisors and merchants from St. Petersburg, as well as Tehran. The Khan naturally, if cautiously, welcomed the foreigners who were willing to help modernise and strengthen his nation. However before long, demands began to arrive via the Russian consulate. The Tsar wished for payment for his services to Khiva, for the right to station troops, and even for the feudal right of vassalage. And so in early 1838, Turkic warriors rounded up Russian and Persian subjects, and with great bluster the Khan demanded the Tsar and Shah to retreat from Khiva and drop all demands. Nicholas must have rubbed his hands with glee. Soon over 30,000 Cossacks were marching towards the frontier to rescue the hostages from the clutches of the vile barbarian.

The Foreign and Colonial Offices were alive with activity, and Lord Palmerston barely slept for a week. Khiva was a domino, the first in a chain that could swiftly see the Russians looking into Afghanistan, or even India. If Britain didn’t act now, there would be little they could later save military action. However Lord Melbourne remained adamant that alternative routes be taken, scared of the corrupt organisation of the East India Company as much as Nicholas I. Much to the collective groan of the British camp, he called on another ‘goodwill mission’ in the region, to attempt negotiations with the Khan. Westminster would be attempting to rescue Russian and Persian agents. As swiftly as possible an expedition set out at speed to the depths of Central Asia. Arriving in late February, the party leader, Lt. Colonel Shakespeare, came bearing gifts of gold and spices, under the guise of a visit to encourage Khiva’s abolition of slavery. In the mere space of several hours, Shakespeare left once, having accomplished his mission. The Hostages were soon released, and Tsar Nicholas glumly called off his invasion. For now.

Over in North America, diplomacy was of a far more civilised affair, though not necessarily any more pleasant. The bankrupt Republic of Texas sought to better relations with Britain and France. In London in June, the Texan representative asked for official recognition of the young state, and a handsome loan to ease reconstruction following the bloody war for independence. Barring the financial implications, the Texans hoped that strong relations with the European Powers would discourage a Mexican revanche. Indeed, their southern neighbour had hardly forgotten the nation of rebellious gringos, particularly as they supported further insurrection in the Yucatan peninsula. However London and Mexico City were relatively close already, and there was strong resistance within the Cabinet and Parliament towards dealing with the Texans. Thomas Rice, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, in particular opposed such a move, fearful of losing influence and trade with Mexico. Radicals in the Commons too argued against even receiving a Texan delegation, on the grounds of their unapologetic stance towards slavery.

Vice-President Lamar of the Republic of Texas

Regardless, Lord Palmerston’s ever-growing influence over Lord Melbourne, and by extension the entire Whig political faction, won through. He saw the poor Anglo nation as a pliable pawn, far more so than Santa Anna’s mercurial Mexico. It was an open secret that despite warm relations between Britain and the United States, it was a long-term Foreign Office goal to deny Washington its ‘Manifest Destiny’. A vast American nation bordering both the Atlantic and Pacific would be an economic and trading powerhouse; a great threat to Westminster’s influence on the continent and further a field. Here Texas and to a lesser extent the rebellious Mexican province of Alta California fitted quite neatly. In Texas the pro-American president, Sam Houston was stepping down and his Vice-President and bitter rival Mirabeau Lamar looked set to win the coming election. A dreadful bigot and jingoist, Lamar led pro-independence supporters and sort to see Texas rival the U.S. Melbourne saw him as someone business could be done with and readily agreed not only to issue loans but secretly bankroll Lamar’s presidential campaign, a miniscule expense in reality but one that quickly endeared him to his new British friends.

Attentions returned to Asia in 1839 as tensions with the Chinese Empire mounted. In March the crown colony of Ceylon raised three regiments of Ceylonese Hussars in order give Britain an offensive force in the region. Similarly a flotilla consisting of four Men-o-War, six Frigates and the newly commissioned Steam-Frigate HMS Volcano set sail for Singapore. Mounting pressure was being put on the East India Company’s operation in Canton regarding its imports of opium. Despite harsh punishments for addicts and traders of the drug, it soon spread across the Middle Kingdom. In turn, the Chinese authorities in Canton, the main port open to Western imports, began to attack the source, arresting and detaining British subjects. Lord Melbourne refused to crack down on the East India Company’s operation, sighting their “autonomy and independence to act as a commercial corporation, they alone will decide their actions”. However this affected the situation little. Finally on July 8th, Chinese soldiers battled British smugglers outside of Canton. Europeans in the city soon came under attack and word was quickly sent to Ceylon and London. On hearing of the events Melbourne and Parliament unanimously called for a declaration of war.

Turkmens, Texans, and Opium, what a combination! And I suppose Lt. Colonel Shakespeare was very articulate in his negotiations?

Excellent to see the government is wise to the many threats it faces, particularly that of the US. We'll have none of this "Manifest Destiny" rubbish thank you very much, far better for the US to once again know the benefits of enlightened British rule.

I also like The Great Game getting the attention it deserves, so often overlooked in AARs, as events are woven into the clash of Great Powers. There will have to be much vigilance of those pesky Russians, mark my words.

I also like The Great Game getting the attention it deserves, so often overlooked in AARs, as events are woven into the clash of Great Powers. There will have to be much vigilance of those pesky Russians, mark my words.

It appears that the domino theory (or indeed the Great Game!) never really went out of fashion. However the Foreign Office is clearly earning its keep with so many plates to keep spinning. I hope, for the sake of Palmerston's health, that these do not all come crashing down at once.

Ironically while perusing some sources for info on the Great Game, I discovered that its a virtual non-entity in Russian history. The only time the Tsars even considered invading India was back during the Napoleonic Wars when they were allied to France. Paul I sent an expedition that got no closer than a thousand miles to the Khyber Pass before he just couldn't be arsed and ordered them back! British fears were just that, I guess the Russians had enough on their plate during the 19th century (Balkans, Poland, the Ottomans, Persia, Manchuria etc.) than to seriously consider annexing a sub-continent with more people, languagues and cultures than their own Empire combined. Indeed the British fought three disasterous wars with Afghanistan seemly due to Russia (and the Soviets later on) setting up consulates in Kabul!

That said this is a Terribly British History so it won't alter this story one jot!

That said this is a Terribly British History so it won't alter this story one jot!

That is one reading. The other is, the many and varied machinations of the British were utterly successful at deterring the Russians who, suitably chastened, airbrushed their ambitions from history to try and expunge the shame.

You can rely on a man called Shakespeare to interest me- subscribed  !

!

Love the title by the way!

Love the title by the way!