So Far From God (Mexico 1836-'76)

- Thread starter ComradeOm

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Lecture Three: Hail to the Chief (1833-1836)

"God has given Us the Papacy; now let Us enjoy it" Leo X

The Mexican Wars of Independence did not see many pitched battles or great military manoeuvres and compared to the Napoleonic Wars, or later 19th C conflicts, it was almost an embarrassingly local affair. Despite this the cost of decades of strife was enormous - up to half a million (a twelfth of Mexico's population at the time) are likely to have perished and a once quietly prosperous economy was left in ruins. For all this bloodshed there was remarkably little progress to show for and post-independence Mexico remained a largely poor agrarian society with great social inequalities and a chronically unstable political establishment. The dominance of the Spanish-born peninsulares was quickly replaced by that of the criollos but there was little to no change in the lives of the peasant population. Significantly the Wars of Independence did not see the emergence of a national movement or any brand of ideologically driven politics; rather the primary loyalties within Mexican society remained to either the local village/province (the patria chica, lit: little homeland) or caudillo (military or political chief), and politics was dominated by personalities and patronage. If some form of an ideological divide did exist in this unstable environment then it was between the conservatives (centralists) and liberals (federalists) but these were very loose collections of like-minded figures more united by Masonic rites and common patronage than real political platforms. Nonetheless it was the federalist clique that dominated the early years of the Mexican Republic and it was a radically liberal Congress that offered Santa Anna the Presidency in 1833 as a reward for marching on and toppling the government of Anastasio Bustamante (1780-1853)

Vice-President Valentín Gómez Farías was de facto ruler of the country during Santa Anna's first term

On establishing himself in Mexico city however the ever mercurial Santa Anna soon found that the daily routine of governing was considerably less entertaining than the pursuit of power itself. As a landowner and soldier Don Antonio had little time for the formalities and frustrations of managing Congress or hammering out backroom political deals, and within a month he had retired to his impressive estates in Veracruz pleading ill health. In doing so he gladly abandoned the tedium of presidential duties to his Vice-President Valentín Gómez Farías (1781-1858)*, an able administrator in the vein of 19th C liberals. Farías was a very different colour of politician than Santa Anna however and he lost little time in initiating a political programme designed to challenge the authority of conservative groups through a series of strident anti-clerical and anti-militarist laws. The initial modest reforms of the Farías administration were accepted, with much grumbling, but moves to completely abolish the traditional privileges (fueros) of the Church and military enraged these powerful institutions and other vested interests. Once again powerful forces began to mobilise against the presidency and, in seeking a champion of their own to overthrow the government, the conservatives begged Santa Anna to return to power and discipline 'his' Congress. Amazingly he agreed - rapidly discarding his liberal credentials, he toppled his own former Vice-President, forcibly dismissed Congress, and came to head a new conservative regime. In April 1834 Santa Anna, the former darling of the liberals who had once raised a revolt in favour of federalism, was returned as president with the backing of the Church, Army, and other conservative organs. Even his staunchest apologists cannot claim that consistency was one of Don Antonio's defining traits

If the new(-ish) President did not bring much added stability to Mexican politics then he seemed to almost compensate by the outrageous colour of his new premiership as he began to firmly establish himself in the capital. The open conservativeness of this regime, with Congress rendered firmly subservient to the executive office, was matched only by its brazen corruption. Mexico's history, pre- and post-independence, had never produced particularly honest administrations but Santa Anna took this to new extremes. Within a year of assuming the Presidency he had become a millionaire and his personal estates around Veracruz continued to swell - to the measure of some 483,000 acres by 1845 - as he systematically channelled vast sums of currency out of the state coffers. If Santa Anna was eager to reap the monetary rewards of office then he was equally keen on using the position to massage his ego and vanity. Not happy with being addressed as "His Excellency", as tradition dictated, the President insisted that the title of "His Most Serene Highness" be used. In a similarly grandiose vein his presence everywhere in the capital was announced by a twenty-one gun salute and accompanied by a personal guard of twelve hundred (the "Lancers of Supreme Power"). Needless to say portraits and busts of the President proliferated throughout the capital and his name was attached to any major construction project during those heady years of excess. Despite his distaste for the routine of governance, and thanks to a natural abundance of charisma and cunning, Santa Anna quickly came to occupy a central position in the tangled web of Mexican politics as both journalist and politician vied to become part of his clique… and thus avail of the extravagant financial and political gifts that he bestowed on friends

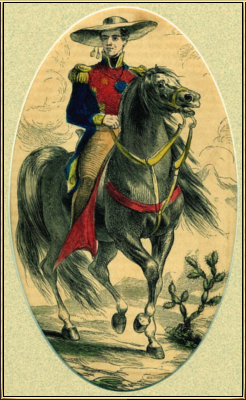

A portrait of the young president enjoying life

All of the above ceremony, pomp, and corruption were of course a huge drain on the Mexican government's finances. The country certainly possessed a sound, if underdeveloped, economic base but the President's constant demands, in addition to continued instability in the countryside, ensured that the government staggered from one financial crisis to another during the 1830s and beyond. The economy never collapsed to the degree that a reliance of foreign loans became necessary but any surplus funds were promptly stolen, to put it bluntly, by Santa Anna and his cronies. The national treasury in effect became the President's personal lifestyle fund with scant resources allocated to anything save the military**. While the government was officially just breaking even, Santa Anna's repeated tenures in office saw vast funds diverted to his personal accounts and estates. This flagrant corruption quickly spread from the top and by 1840 the Mexican state apparatus (relatively honest during colonial times) was thoroughly rotten with almost all positions of power occupied by venal kleptocrats. In turn this fuelled the rise of local caudillos and contributed to increased instability throughout the country

Amid all the vanity projects, grandiose gestures, and rampant womanising, however, there was some real political reform during these early years. Santa Anna had ultimately been persuaded to return to the presidency, and oppose the federalists that he had once supported, by the plea for stability. Increasingly styling himself as a neutral arbitrator, and ever scornful of factional politics, the public image of Don Antonio was that of a devoted servant to Mexico who sought the best for the nation regardless of ideology or personal conflict. Notably he had not disagreed with the actual substance of the Farías reforms but made clear that he felt the radical Congress was moving too fast and recklessly in enacting them. Similarly, he was not afraid to tear down the very constitution that he had once risked his career for now that its weaknesses had become apparent. In late 1835 Santa Anna turned his attention to the very structure of the Republic as he sought to replace the Constitution of 1924 with one of his own creation. This document had been a major early victory for the federalist movement and was closely modelled on that of the United States, a nation that most liberal Mexican politicians were effuse in their praise for, in that it dictated that the country was to be governed as a federal republic with considerable power vested in the provinces with a correspondingly weak central government. Conservative politicians certainly had good reason to object to this arrangement and a revision of the constitution was one of their primary political aims following the establishment of the Mexican Republic. In Santa Anna they had found a decisive agent of change and in late 1835 the President engineered the passing of the Siete Leyes (Seven Laws) that would form the basis of the new Constitution of 1836. The essence of these constitutional changes was a shifting of much power from the provinces to central government in Mexico City, although the country would remain in essence a federal state. While this was a sound political move†, it was naturally unpopular with the provincial governments who found their independence suddenly curtailed. There was a flurry of pronunciamientos issued against the central government as militias in many Mexican states took up arms to protect their privileges. True to his character and background Santa Anna relinquished the presidency in early 1836 in favour of a military command as he set out to quash the armed revolts that had sprung up in opposition to the new constitution. By far the most serious of these incidents was located in the errant province of Texas where simmering tensions had erupted into a fully fledged war of independence in late 1835. The Texan Revolution, as it is often romantically portrayed, presented Santa Anna with his most formidable challenge to date and the outcome would have far-reaching consequences for both his career and Mexico

-----

* One of the more eccentric (of many!) practices of Santa Anna was his tendency to abandon the Presidency to an aide or ally when he tired of the duties of state or was forced to take to the field of battle. Valentín Farías was the first of these but other presidents such as Miguel Barragán (1789-1836) and José Justo Corro (1794-1864) were closely aligned with Santa Anna. Even when temporarily out of office, a regular occurrence, his influence on Mexican politics was immense

** Education was largely unaffected due to the presence of privately funded Church schools and missions. Higher education was reserved for the few thousand members of the clergy and nobility but there was nonetheless a general increase in literacy during the period. In addition, and perhaps surprisingly, Santa Anna himself proved to be a generous patron of educational institutions during his various premierships and the attempts of Farías to secularise the education system were actually furthered during later santanista regimes

† In hindsight the federal Constitution of 1824 can be seen as a misguided, if well-intentioned, effort and completely unsuited to the turmoil of post-independence Mexico. Historians have generally singled out the Constitution of 1836 as one of the more important contributions of Santa Anna to the evolution of the Mexican state. However, if the increased centralisation is generally praised then the clauses that served to buttress the conservative lobby (landowners, officers, and the clergy) and limit democratic participation (such as raising the wealth limit on voting) are somewhat less admired today

So this brings us to the end of the pre-game introduction. Not a huge degree is going to change (format-wise) for the rest of the AAR but I'll at least be able to reference the gameplay events. Of course a Mexico game starts off with a bang and revolt in Texas...

Apologies to those who were expecting a tutorial on trailers this week. I have one written up but wasn't able to find time to format it and get it ready for posting. If I'm on the internet during the week then I'll to stick it up, otherwise it will have to wait til next weekend

The above opening frame are notes from the Te Deum, a religious hymn/chant/song. In a tradition that goes back to Cortez, Mexican victors would retire to the cathedral on taking/entering Mexico City to be received by this hymn

Phew, those comments below took longer than I expected. Generally if I write a paragraph or two in response its because I've been thinking about that particular point, in my own self-critical manner, beforehand. Feel free to take up any point and elaborate or discuss if you wish

robou: Probably the best description of Santa Anna that I've read is 'Always clever, never wise'. That about sums the man up and its one reason why its very hard to get a handle on his personality. For example, in the above update I can't see any reason why Santa Anna renounced the presidency (although technically he remained in office) other than sheer boredom!

J. Passepartout: One of the first things that struck me when doing the research for this AAR was that biographies on Santa Anna (Fowler's work excepted) tend to be part of the US or Mexican traditions - which portray him as an inept tyrant or a treasonous tyrant respectively. There are very few neutral works out there... a shame seeing as the man was obviously very talented. I mean, he'd have to be given the number of times he recovered from his own blunders

Eams: The big problem with going into detail, and this is something that I'm actively worrying about, is that it would easily triple the length of this AAR. If you cast your eyes to the AAR Introduction you'll see that I'm keeping track of the rulers of post-Independence Mexico and we already have nine regimes after two updates! I can't see a way to delve into the motives of the characters, aside from Santa Anna (an incredibly complex character), without either update length doubling and the progress of the AAR coming to a halt. What I'm currently trying to do is let the actions of the characters speak for themselves and only rarely, most notably in the case of Santa Anna, make their motivations explicit

As I say, this troubles me because I recognise that this attention to detail and subtle motivations is what makes great political AARs, like Dr Gonzo's effort, work. Now that we're entering the game timeframe I expect the pace to slow down slightly so let me know in a few updates time if this is still a major issue

Ladislav: Cheers. I'm very particular about the presentation of my AARs and I think its hugely important to get right. Unfortunately Mexico doesn't offer as many striking graphics as the Papal States did but I'm managing. I did a tutorial on how to apply Vicky borders to graphics here

English Patriot: Santa Anna just isn't somebody that we hear about over on this side of the Atlantic. I'd imagine that our US posters would know him as an early boogeyman of the USA but it wasn't until Director's AAR that the name meant anything to me. Well, not quite, I did vaguely remember him as the dictator who had a funeral for his own leg (we'll get to that...)

Capibara: You know, this is the forth AAR in which I asked people to correct historical errors and I think this is the first person to mention one. Thanks

GregoryTheBruce: Cheers. If I can give you two pieces of advise on writing an AAR (and I'm really not qualified to ). One, don't go overboard on the introductions. This is somewhat of an unusual case but usually I'd restrict myself to, at most, a single background update dealing with the recent past. Some writers tend to go too far and sketch out centuries of history but really most readers are just waiting for the actual alt-history to start

). One, don't go overboard on the introductions. This is somewhat of an unusual case but usually I'd restrict myself to, at most, a single background update dealing with the recent past. Some writers tend to go too far and sketch out centuries of history but really most readers are just waiting for the actual alt-history to start

Secondly, panning is important in an AAR but I've yet to sit down and plan one out from the start with custom events et al. Usually I'll pick a nation I enjoy playing, put in a few hours game time, and see how the story evolves from that. Others might do it differently but for your first AAR I wouldn't get too caught up in creating a unique setup

As for footnotes, the only way that I can see to hyperlink them would be to create a new footnote post after the main update body. Its not worth it though - originally I was going to include links at the bottom of each post taking the reader to the previous/next update but messing around with links and formatting is more trouble than its worth

Irenicus: Oh I always play to my best in AARs. Granted, ever since my first effort I tend to pause at some point and proceed to tear everything down but, as yet, I've no plans for custom events or major collapses. This may well change as I complete the game but I obviously don't want to give anything away so soon

Of course its not significantly important in this AAR as 90% of the content in updates is entirely of my own creation. Even when Mexico is doing well in game I'll be filling in the 'boring' years of peace with domestic turmoil

Then again if I was continually losing it wouldn't be all that different from history

stnylan: Fingers crossed that I can, unlike Les Journals, sustain the interest. And Santa Anna really had a knack for either recovering from defeat or generally capitalising on events. Uncanny really, the man just never gave up

Cinéad IV: You may be in for a fall then. With Sins everything just went right. Others AARs were... not so smooth

asd21593: Thanks. Be warned though, I have no immediate plans for a commie Mexico!

Apologies to those who were expecting a tutorial on trailers this week. I have one written up but wasn't able to find time to format it and get it ready for posting. If I'm on the internet during the week then I'll to stick it up, otherwise it will have to wait til next weekend

The above opening frame are notes from the Te Deum, a religious hymn/chant/song. In a tradition that goes back to Cortez, Mexican victors would retire to the cathedral on taking/entering Mexico City to be received by this hymn

Phew, those comments below took longer than I expected. Generally if I write a paragraph or two in response its because I've been thinking about that particular point, in my own self-critical manner, beforehand. Feel free to take up any point and elaborate or discuss if you wish

-----

robou: Probably the best description of Santa Anna that I've read is 'Always clever, never wise'. That about sums the man up and its one reason why its very hard to get a handle on his personality. For example, in the above update I can't see any reason why Santa Anna renounced the presidency (although technically he remained in office) other than sheer boredom!

J. Passepartout: One of the first things that struck me when doing the research for this AAR was that biographies on Santa Anna (Fowler's work excepted) tend to be part of the US or Mexican traditions - which portray him as an inept tyrant or a treasonous tyrant respectively. There are very few neutral works out there... a shame seeing as the man was obviously very talented. I mean, he'd have to be given the number of times he recovered from his own blunders

Eams: The big problem with going into detail, and this is something that I'm actively worrying about, is that it would easily triple the length of this AAR. If you cast your eyes to the AAR Introduction you'll see that I'm keeping track of the rulers of post-Independence Mexico and we already have nine regimes after two updates! I can't see a way to delve into the motives of the characters, aside from Santa Anna (an incredibly complex character), without either update length doubling and the progress of the AAR coming to a halt. What I'm currently trying to do is let the actions of the characters speak for themselves and only rarely, most notably in the case of Santa Anna, make their motivations explicit

As I say, this troubles me because I recognise that this attention to detail and subtle motivations is what makes great political AARs, like Dr Gonzo's effort, work. Now that we're entering the game timeframe I expect the pace to slow down slightly so let me know in a few updates time if this is still a major issue

Ladislav: Cheers. I'm very particular about the presentation of my AARs and I think its hugely important to get right. Unfortunately Mexico doesn't offer as many striking graphics as the Papal States did but I'm managing. I did a tutorial on how to apply Vicky borders to graphics here

English Patriot: Santa Anna just isn't somebody that we hear about over on this side of the Atlantic. I'd imagine that our US posters would know him as an early boogeyman of the USA but it wasn't until Director's AAR that the name meant anything to me. Well, not quite, I did vaguely remember him as the dictator who had a funeral for his own leg (we'll get to that...)

Capibara: You know, this is the forth AAR in which I asked people to correct historical errors and I think this is the first person to mention one. Thanks

GregoryTheBruce: Cheers. If I can give you two pieces of advise on writing an AAR (and I'm really not qualified to

Secondly, panning is important in an AAR but I've yet to sit down and plan one out from the start with custom events et al. Usually I'll pick a nation I enjoy playing, put in a few hours game time, and see how the story evolves from that. Others might do it differently but for your first AAR I wouldn't get too caught up in creating a unique setup

As for footnotes, the only way that I can see to hyperlink them would be to create a new footnote post after the main update body. Its not worth it though - originally I was going to include links at the bottom of each post taking the reader to the previous/next update but messing around with links and formatting is more trouble than its worth

Irenicus: Oh I always play to my best in AARs. Granted, ever since my first effort I tend to pause at some point and proceed to tear everything down but, as yet, I've no plans for custom events or major collapses. This may well change as I complete the game but I obviously don't want to give anything away so soon

Of course its not significantly important in this AAR as 90% of the content in updates is entirely of my own creation. Even when Mexico is doing well in game I'll be filling in the 'boring' years of peace with domestic turmoil

Then again if I was continually losing it wouldn't be all that different from history

stnylan: Fingers crossed that I can, unlike Les Journals, sustain the interest. And Santa Anna really had a knack for either recovering from defeat or generally capitalising on events. Uncanny really, the man just never gave up

Cinéad IV: You may be in for a fall then. With Sins everything just went right. Others AARs were... not so smooth

asd21593: Thanks. Be warned though, I have no immediate plans for a commie Mexico!

ComradeOm said:asd21593: Thanks. Be warned though, I have no immediate plans for a commie Mexico!

No!!!!

Great update by the way

A most excellent introduction if i may say so. And now let us see if Santa Anna can make a better show of Mexico than in real life... no San Jacinto's here i hope!

Now we get into the part that is more of the character portrayed in my high school history classes.  Interesting.

Interesting.

Are there any that you would recommend? I take it from your phrasing that Fowler is good. I have not read any books specifically about the man, gathering everything from books on related subjects or from classes.

that biographies on Santa Anna (Fowler's work excepted) tend to be part of the US or Mexican traditions

Are there any that you would recommend? I take it from your phrasing that Fowler is good. I have not read any books specifically about the man, gathering everything from books on related subjects or from classes.

So now Santa Anna marches to the north and the difficult challenges awaiting him there, he leaves behind a messy situation that could turn on him in an instant.

I think it is fair to say that Santa Anna lives somewhat on the edge.

I think it is fair to say that Santa Anna lives somewhat on the edge.

Been away a while, I didn't realise you'd returned Om, just caught, great stuff. Thank you for the praise but considering your quality to date, I doubt you'll fail to hit the bar once more.

On to Texas!

On to Texas!

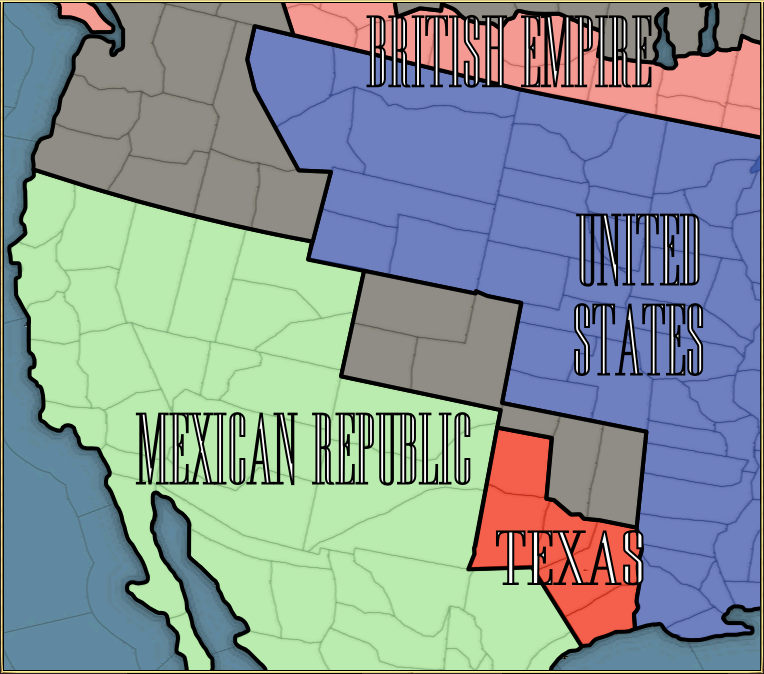

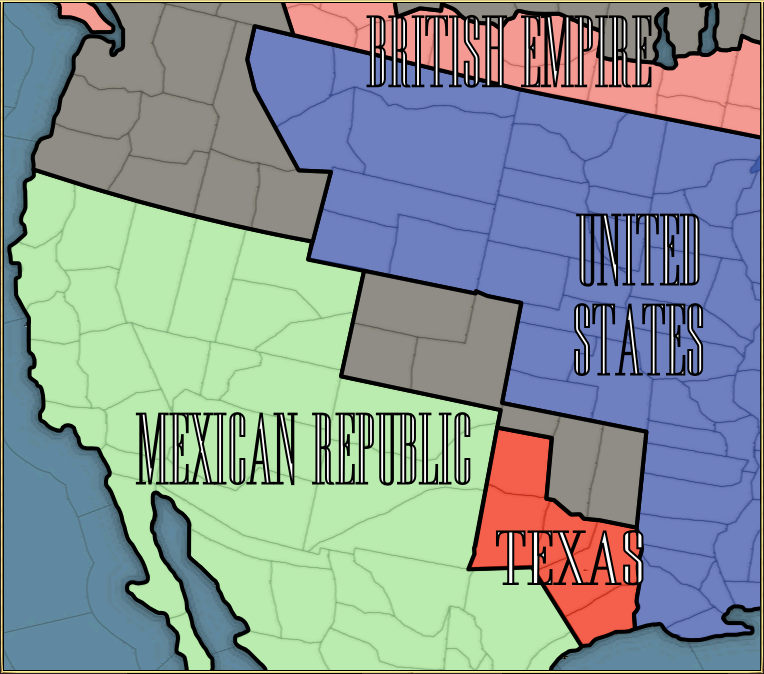

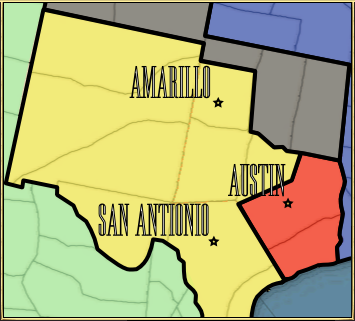

North America in 1836

-----

-----

Thanks for the feedback all. Update and responses will follow some time tomorrow. For now see above for the strategic situation in 1836. I think I'll do one of these large maps every so often as they don't really fit into narrative proper

I'd forgotten how clean the map looks without VIP  . Btw, i have started using Inkscape (which i believe you used for that map) and it is great, thanks for telling us about that! Ironiclly, the map i annotated was a map of Mexico

. Btw, i have started using Inkscape (which i believe you used for that map) and it is great, thanks for telling us about that! Ironiclly, the map i annotated was a map of Mexico

Lecture Four: Fire and Death (1836-'37)

"[Mexican soldiers] intend to compel you into obedience to the new form of government; to compel you to give up your arms; to compel you to have your country garrisoned; to compel you to liberate your slaves"

RM Williamson

If the outbreak of armed revolts that accompanied the passing of the centralist Constitution of 1836 was predictable then it was equally of little surprise when Texas became the first Mexican province to formally announce independence and secede from the confederacy. A generation of high migration from the United States (the borders had first been opened by the Spanish Crown in 1821) had created an independent-minded community and culture that shared very little in common with Mexico City, its nominal government. In little over a decade there were over thirty thousand new Mexican citizens of Anglo-Saxon Protestant character (some 78% of the Texan population by 1835) and a corresponding rise in racial tension in the region*. Early Texan complaints had largely focused on increasing their representation within the Republic but tempers had been escalating steadily throughout the years and by the time Santa Anna introduced the centralist Constitution of 1836 there was little mood for compromise. It had previously been possible for Texan legislators at Austin to effectively ignore many laws from Mexico City, including those on slavery, but the new constitution threatened to end this quasi-independence. Rejecting the prospect of becoming increasingly subsumed into the Mexican state, and a 'foreign' culture, many Texans came to believe that only open revolt and formal independence would suffice to safeguard their way of life. Skirmishing between settler militias and the National Army steadily intensified throughout 1835 but it was the passing of the Siete Leyes that sparked the decisive break. In early 1836 those Mexican army detachments still stationed in the province were driven out by a determined settler campaign and the Lone Star Republic was formally declared on 2 March 1836. A provisional government, under David G. Burnet (1788-1870), was quickly established, its first task being defending itself against the inevitable response from Santa Anna**

The territory claimed by the new Republic of Texas was very different from that of the former Mexican state. On independence the Texan militias extended their borders not to the Nueces River, the traditional boundary of the province, but as far south as the Rio Bravo (known in the US as the Rio Grande). This was a vast increase in area, with the potential for future expansion to the north east to encompass New Mexico, into lands in which Texans had only sparsely settled previously. These grandiose claims were given added weight not just by Texan military successes in late 1835 and early 1836 but by the rapt attention of the United States of America. Indirect US influence was felt heavily by all parties with many influential figures within the States staunch supporters of Texan independence. As the bitterness of slave politics slowly crept into US political discourse many Southern Democrats became convinced that westward expansion, dependant on Texan admittance into the Union, was the only way to safeguard the future of slavery, and thus their way of life, in the face of abolitionist sentiment. Other more idealistic commentators, such as journalist John O'Sullivan (1813-1895), saw parallels with the original American Revolution and advocated US expansion as part of some divine and admirable Manifest Destiny. To the latter the independence of Texas and its peaceful admission into the Union would be the vindication of the ideals upon which the USA itself had been founded. Both positions were heavily underpinned by a base racism, and Manifest Destiny obviously seems extremely quaint today, but they did resonate with large sections of the US public. Filibustering expeditions by private armies into Mexican territory remained unsanctioned by Washington DC but they drew the attention of the US press and ensured that the plight of Texas would have ramifications far beyond that of a mere local revolt†

Map of the Texas Campaign illustrating the Mexican province of Texas (red), Texan territorial claims on Mexico (yellow) and major battles fought by

It is to Santa Anna's credit that he recognised the seriousness of the Texan revolt and suppressing it immediately became his top priority on renouncing the presidency in favour for a military commission in early 1836, placing José Justo Corro at the helm of the nation. With typical panache he decided to commit all to 'pacifying' Texas in the expectation that a strong showing in the north would strengthen his position further south. Given the fragmented nature of the National Army, with generals owing their positions to local power politics or patronage, it was necessary to barter with the various army commanders in order to ensure the order to march north was actually obeyed. While the palms of semi-independent generals were liberally greased Santa Anna himself set about the task of assembling his own army in Mexico City. In the last days of 1835 he began to move north with over six thousand men and some typically modest sentiments:

"I, as chief executive of the government, zealous in the fulfilment of my duties to my country, declared that I would maintain its territorial integrity whatever the cost. This would make it necessary to initiate a tedious campaign under capable leadership immediately… Stimulated by courageous feelings I took command of the campaign myself, preferring the uncertainties of war to the easy and much coveted life of the palace"

As it was the campaign in Texas was anything but tedious and Santa Anna almost immediately encountered infamy. After some light skirmishing around Revilla, his Ejercito de Operaciones (Army of Operations) crossed the Rio Bravo on 12 February 1836 and approached San Antonio de Béxar where a group of Texans, under William Barrett Travis, had fortified themselves in an old Franciscan monastery known as the Alamo. After a short but furious siege the rebels capitulated and the survivors faced with a short and grim future. Santa Anna was a veteran of the brutal guerrilla wars of Mexican Independence and his military education had not covered showing mercy to defeated foes – the mere five Texans that survived the siege were promptly executed. When a much larger Texan army was defeated by General José Urrea, at the small town of La Bahía (Goliad) two weeks later, the commander's instructions were again unmistakably clear. In total 365 prisoners of war were executed by Urrea's men after Santa Anna explicitly classified them as pirates and ordered their deaths. Such callous behaviour was almost rewarded in kind when a Texan army under Sam Houston came agonisingly close to routing the Mexican invasion force at the Battle of San Jacinto. Having failed to post sentries for the night, or take any other precautionary measure, Santa Anna's army was surprised on the morning of 21 April by a small but determined Texan assault. Disaster was only averted when reinforcements from the south made a timely arrival to bolster the beleaguered and chaos-ridden Mexican formations. Somehow their lines held and the rebels were forced to withdraw in disarray after a few hours of fighting. This was to be the last major engagement of the Texan Revolution as Santa Anna capitalised on his victory by retaking the strategic initiative and hounding the surviving rebel units without mercy. Three weeks later the provincial capital of Austin was seized by Mexican soldiers and the small settlement razed

The pivotal battle of San Jacinto as the Texan assault on Santa Anna's camp is repelled

Over the next several months the remaining Texan forces were systemically scattered or destroyed as Mexican armies moved to assert control of the errant province. The revolt effectively ended with the brief Battle of Amarillo in which the last armed bastion of the Lone Star Republic was overwhelmed by the Ejercito de Operaciones in early December 1836. A number of prominent Texan figures (including Sam Houston) escaped into the United States following this defeat but Santa Anna felt comfortable enough to offer an amnesty to the remaining rebel soldiers on the condition that they promptly surrender their arms. Such offers were common during the Mexican Wars of Independence and it may be that the general was already eager to return south to snuff out the many other rebellions against his rule. There was no formal peace treaty with Texas, its independence having never been recognised by Mexico City, but the resulting peace was nonetheless harsh. The Texan Republic was once again to be folded into Mexico while all dreams of independence or autonomy were naturally abandoned. In addition Santa Anna decided to maintain a large garrison along the border. This would both secure the region from further revolt, or US interference, and conveniently remove many of his generals from their southern powerbases. The estates of major rebels were also confiscated and plots of land were offered to soldiers who had participated in the campaign. Such measures proved unpopular with the Texans, who were also expected to shoulder the costs of these new border armies, but there was little recourse for the defeated. For the Mexican soldiers victory brought little but the prospect of renewed fighting as Santa Anna turned his attention back to Central Mexico

-----

* The potential for sedition in Texas had long been recognised by successive presidents during the early Republic and Santa Anna himself had heavily encouraged Mexican migration to the region to counterbalance the influence of US settlers. Previous presidents had increased the presence of the national military along the border and the anti-slavery bill of President Vicente Guerrero (1829) was clearly aimed at the Texans, who were the only major slave-owners within the Mexican Republic. See 'Williams, D., (1997), Bricks Without Straw: A Comprehensive History of African Americans in Texas' for a study of slavery in the province

** It should not be forgotten that a number of Spanish-speaking Mexicans also supported the independence of Texas. The federalist position was represented in Austin by Lorenzo de Zavala (1788-1836) who argued that through its 'tyranny' Mexico City had forfeited all claims to rightful governance. See, 'Davis, W.C., (2004), Lone Star Rising: The Revolutionary Birth of the Texas Republic'

† Probably the best known of these filibusters was the James Long expedition of 1819. A small army of roughly 300 US soldiers of fortune, led by Doctor Long, crossed into Spanish Mexico and occupied the border town of Nacogdoches before declaring an independent Texan Republic. The expedition was driven off but Long returned to Mexico in 1821 at the head of a much smaller party. This time he was arrested and shot while in captivity. Long, and other expeditions, are dealt with in 'Warren, H.G., (1972), The Sword was Their Passport: A History of American Filibustering'

First of all I have to confess that there are two historical inaccuracies in the above piece (that I'm aware of!). In the first case Texas was not actually a formal state in the Mexican Republic but its often referred to as one and its not the sort of minor detail I want to spend time distinguishing between. More importantly, Austin was not the capital of Texas in 1836 (indeed the tiny settlement was called 'Waterloo' at the time) but in circumstances such as this I tend to accept Victoria's version to avoid confusion amongst the redaers

Anyways, we've finally hit the actual game timeframe. Unfortunately it was only a few decades later that I realised that this would make a good AAR so I have no notes to fall back on. I do intend however to keep up a quick running commentary on in-game events here in the commentary. Of course there's not much to say - unlike VIP, vanilla Vicky treats Mexico as a standard unitary state with no domestic upheaval. Its a real problem with the game engine and the reason why much of this AAR is effectively fiction. Similarly, the country is poor but still showing a profit and, as a result of both this and tranquillity at home, the Texas Revolution is very easy to put down. Even the AI manages it 99% of the time. Still, that's Vicky for you

Yet again, sorry about the lack of trailer tutorial. Its the same excuse as last time - I have the thing drawn up but I'm struggling to find the hour or two needed to polish it up for posting. You'll see it this time next week at the latest

asd21593: Glad you like the map. To be honest one of the things that I've always loved about making AARs (far more so than the actual writing) is spending time on the graphics. Maps like this are particularly fun to create and I do like the end result

robou: Well as you can see above, San Jacinto forms the POD for this AAR. There will be others but this is the primary 'What If' moment

I'm actually sorry that I didn't play this game with VIP... I get the feeling that the mod really shakes up North America. As for Inkscape, and I can't remember if you saw this before or not, but I posted a map tutorial for the program here

J. Passepartout: Well I don't want to come across as too soft of the man (although most of the mentioned excesses actually date from his later reigns) so its useful to remind everyone that Santa Anna did have his flaws

I did enjoy Fowler's work but then I'm coming from a country where is man, and the myths that surround him, are almost completely unheard of. It is most certainly a revisionist work (and I get the feeling that it might be slightly too sympathetic towards its subject) but Fowler seems to approach Santa Anna from an entirely new angle and it is very balanced. I'd definitely recommend it if you have an interest in the man... or you could just read this AAR

Capibara: Well this wouldn't be much of an AAR, and I wouldn't be much of a player, if I fell at the first hurdle

Which reminds me about the above update - in the game I took the standard peace treaty (humiliation and every province except Austin) but that obviously doesn't fit in with the narrative. So in the AAR you can consider Texas to be both crushed and entirely reintegrated into the Mexican nation

stnylan: That is what is so entertaining about Santa Anna - he was not one for moderation or considering the odds. Almost every move he made was a political or military gamble... living on the edge indeed

And you're perfectly correct to note that Texas was not the only source of instability in Mexico...

Dr. Gonzo: Meh, don't be so modest. As far as I'm concerned your 'Terribly British History' has set the standard for political AARs. Speaking of which... let's have another update from you. Two in the space of a fortnight would be novel indeed

CCA: Well the end of this AAR isn't written yet but I am finishing long before the historical revolution of 1910. I won't rule anything out but don't get your hopes up

Anyways, we've finally hit the actual game timeframe. Unfortunately it was only a few decades later that I realised that this would make a good AAR so I have no notes to fall back on. I do intend however to keep up a quick running commentary on in-game events here in the commentary. Of course there's not much to say - unlike VIP, vanilla Vicky treats Mexico as a standard unitary state with no domestic upheaval. Its a real problem with the game engine and the reason why much of this AAR is effectively fiction. Similarly, the country is poor but still showing a profit and, as a result of both this and tranquillity at home, the Texas Revolution is very easy to put down. Even the AI manages it 99% of the time. Still, that's Vicky for you

Yet again, sorry about the lack of trailer tutorial. Its the same excuse as last time - I have the thing drawn up but I'm struggling to find the hour or two needed to polish it up for posting. You'll see it this time next week at the latest

-----

asd21593: Glad you like the map. To be honest one of the things that I've always loved about making AARs (far more so than the actual writing) is spending time on the graphics. Maps like this are particularly fun to create and I do like the end result

robou: Well as you can see above, San Jacinto forms the POD for this AAR. There will be others but this is the primary 'What If' moment

I'm actually sorry that I didn't play this game with VIP... I get the feeling that the mod really shakes up North America. As for Inkscape, and I can't remember if you saw this before or not, but I posted a map tutorial for the program here

J. Passepartout: Well I don't want to come across as too soft of the man (although most of the mentioned excesses actually date from his later reigns) so its useful to remind everyone that Santa Anna did have his flaws

I did enjoy Fowler's work but then I'm coming from a country where is man, and the myths that surround him, are almost completely unheard of. It is most certainly a revisionist work (and I get the feeling that it might be slightly too sympathetic towards its subject) but Fowler seems to approach Santa Anna from an entirely new angle and it is very balanced. I'd definitely recommend it if you have an interest in the man... or you could just read this AAR

Capibara: Well this wouldn't be much of an AAR, and I wouldn't be much of a player, if I fell at the first hurdle

Which reminds me about the above update - in the game I took the standard peace treaty (humiliation and every province except Austin) but that obviously doesn't fit in with the narrative. So in the AAR you can consider Texas to be both crushed and entirely reintegrated into the Mexican nation

stnylan: That is what is so entertaining about Santa Anna - he was not one for moderation or considering the odds. Almost every move he made was a political or military gamble... living on the edge indeed

And you're perfectly correct to note that Texas was not the only source of instability in Mexico...

Dr. Gonzo: Meh, don't be so modest. As far as I'm concerned your 'Terribly British History' has set the standard for political AARs. Speaking of which... let's have another update from you. Two in the space of a fortnight would be novel indeed

CCA: Well the end of this AAR isn't written yet but I am finishing long before the historical revolution of 1910. I won't rule anything out but don't get your hopes up

So he's managed to deal with Texas for now - though I would not be surprised if Texas were to cause trouble in the future.

Let us hope Santa Anna is good enough to learn from his mistakes at San Jacinto, even if he did walk out of the battle a victor. That tutorial was the place i found Inkscape

Here's to Santa Ana

I look forward to seeing how the crushing and integration of Texas will by taken in the US.

While VIP is more historically accurate, you'll have a bit more freedom of action playing Vanilla. When war eventually breaks out with the Big Blue Blob, don't claim those areas where the US has trade posts. Simply capture them, and use them as future bargaining chips when you eventually have good relations. Use any money you get from such deals to fortify your borders well, because the Americans will be back.

I look forward to seeing how the crushing and integration of Texas will by taken in the US.

While VIP is more historically accurate, you'll have a bit more freedom of action playing Vanilla. When war eventually breaks out with the Big Blue Blob, don't claim those areas where the US has trade posts. Simply capture them, and use them as future bargaining chips when you eventually have good relations. Use any money you get from such deals to fortify your borders well, because the Americans will be back.

Good to see the Texans defeated, it's now time for Santa Anna to strengthen his position in Mexico City