((A private letter to @naxhi24 ))

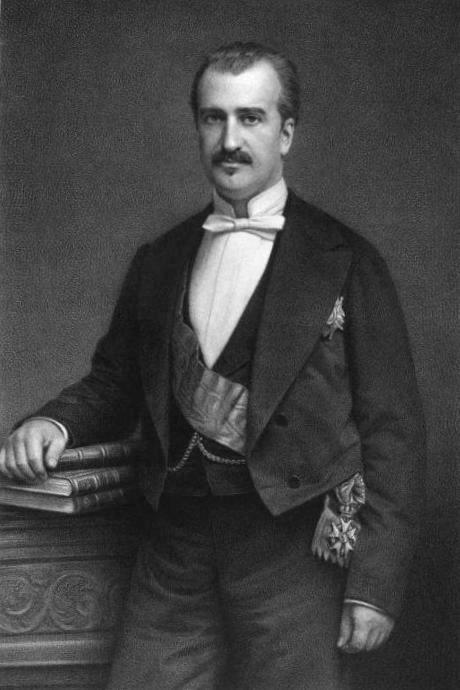

To Baron A Descombes, Chateau Descombes, Doubs

My dear friend, Alexandre,

I trust this letter finds you in rude health and good spirits. I certainly hope that you are enjoying the opportunity to relax with your wife and children, following your prodigious efforts over the last 2 years.

Firstly, I congratulate you on your achievement of the return of a King to France. As you know, I have no great desire to see a Bourbon hold sway over our Nation again, not least one who has been absent from our shores for the vast majority of his life. Nevertheless, although we may sit on opposite sides of the Chamber, I hope our friendship may still meet in the middle, and I feel duty bound to offer you the praise that you so richly deserve for bringing off an achievement which to be perfectly frank, flies in the face of reason, or at least reason as we knew it 22 years ago. Although others of the King's supporters may claim the credit, it has been your sensible steadiness in the face of the crisis which achieved what so many did their level best to frustrate through their arrogance and belligerence.

This brings me to my second point, and my concern as to the possibly bitter fruits of your labours. My friend, I am greatly concerned that the atavism demonstrated by Legitimists may derail the efforts made to advance a modern France. You will well recall the anachronistic attitudes of Charles X and his coterie. Now we are saddled with Charles' grandson, a man who spent barely 10 years of infancy in France, accustomed to the fawning of émigré courtiers in England, and privilege of a life untested in achievement. We see how he has been gifted the throne of the most puissant Country on Earth through no greater effort of getting off a boat. Prizes earnt by little effort are little valued, and I fear that we will face a repeat of the detachment from weighty burden of national responsibility which has plagued France under Bourbon kings past.

To that end, what means are proposed in the Constitution to keep the caprices of the King in check? It is easier to rein in a President who is answerable to an electorate than it is to control a King who is answerable to no one. You and I certainly do not want a repeat of 1830 when the Royal party attacked our banks in a pique of vitriol towards men who earn their livings. The Bourbons think they rule by the will of God, whereas the Constitution should ensure that they rule by the will of the People.

And what means are there to be for parliamentary oversight of the conduct of the executive? I am particularly concerned that we will see the repeat of the days before 1830 where the Royal hand arbitrarily gifted the assets of the State to the sycophants and the venal who flattered and fauned their way to wealth.

I fear that such corruption has already begun to infect the blood of our Government. I noted the arrival of the King on a vessel formerly of our Navy, but was informed that it now belonged to a private concern, the Compagnie des Messageries Maritime. My agents made enquiries and found an obscure proclamation made by the Comte de la Marche, in his capacity as interim President, during thedying days of the Republic. The Comte gift 14 large transport vessels to the Messageries Maritime, for no valuable consideration whatsoever. My agents further discovered that this company is owned by no less a personage as the Prince de Polignac.

I have no problems with the State offering its assets for sale, and the use of those assets in the most commercially efficient manner possible. I for one would gladly had bid for such shipping if it had been offered by public tender. However, the surreptious largesse of 14 ships to a Prince du sang from a President supposed to be in caretaker mode does raise alarms as to the cupidity which we might expect unless there are the proper checks and balances contained in the Constitution to stamp out corruption.

In the expectation that the new regime will recognize and reward your untiring efforts, I would ask that, as a friend devoted to fiscal and moral rectitude, you investigate this transaction further and take the appropriate judicial and remedial steps to restore public confidence in the accountability of the Government under its new master.

Finally, I and the Grand Sanhedrin have been considering a proposal to promote the French cause amongst our brethren in Algeria. The local Jewish population has been most helpful as guides and suppliers to the French Army in their struggle against the local insurgents. We feel that by providing schools to educate our brethren in our ways, the Jewish people may become servants of France and maybe one day, citizens of our fair Nation. Given your elevation contrary to my position in opposition, I would appreciate your advocacy and sponsorship of this proposal in the Government which is to come.

Please visit when you return to Paris for the constitutional debates. Betty and I would love to dine with you and your wife, and reminisce over those glorious days of our youth .

I remain, dear Sir, your devoted friend,

Jacques de Rothschild

To Baron A Descombes, Chateau Descombes, Doubs

My dear friend, Alexandre,

I trust this letter finds you in rude health and good spirits. I certainly hope that you are enjoying the opportunity to relax with your wife and children, following your prodigious efforts over the last 2 years.

Firstly, I congratulate you on your achievement of the return of a King to France. As you know, I have no great desire to see a Bourbon hold sway over our Nation again, not least one who has been absent from our shores for the vast majority of his life. Nevertheless, although we may sit on opposite sides of the Chamber, I hope our friendship may still meet in the middle, and I feel duty bound to offer you the praise that you so richly deserve for bringing off an achievement which to be perfectly frank, flies in the face of reason, or at least reason as we knew it 22 years ago. Although others of the King's supporters may claim the credit, it has been your sensible steadiness in the face of the crisis which achieved what so many did their level best to frustrate through their arrogance and belligerence.

This brings me to my second point, and my concern as to the possibly bitter fruits of your labours. My friend, I am greatly concerned that the atavism demonstrated by Legitimists may derail the efforts made to advance a modern France. You will well recall the anachronistic attitudes of Charles X and his coterie. Now we are saddled with Charles' grandson, a man who spent barely 10 years of infancy in France, accustomed to the fawning of émigré courtiers in England, and privilege of a life untested in achievement. We see how he has been gifted the throne of the most puissant Country on Earth through no greater effort of getting off a boat. Prizes earnt by little effort are little valued, and I fear that we will face a repeat of the detachment from weighty burden of national responsibility which has plagued France under Bourbon kings past.

To that end, what means are proposed in the Constitution to keep the caprices of the King in check? It is easier to rein in a President who is answerable to an electorate than it is to control a King who is answerable to no one. You and I certainly do not want a repeat of 1830 when the Royal party attacked our banks in a pique of vitriol towards men who earn their livings. The Bourbons think they rule by the will of God, whereas the Constitution should ensure that they rule by the will of the People.

And what means are there to be for parliamentary oversight of the conduct of the executive? I am particularly concerned that we will see the repeat of the days before 1830 where the Royal hand arbitrarily gifted the assets of the State to the sycophants and the venal who flattered and fauned their way to wealth.

I fear that such corruption has already begun to infect the blood of our Government. I noted the arrival of the King on a vessel formerly of our Navy, but was informed that it now belonged to a private concern, the Compagnie des Messageries Maritime. My agents made enquiries and found an obscure proclamation made by the Comte de la Marche, in his capacity as interim President, during thedying days of the Republic. The Comte gift 14 large transport vessels to the Messageries Maritime, for no valuable consideration whatsoever. My agents further discovered that this company is owned by no less a personage as the Prince de Polignac.

I have no problems with the State offering its assets for sale, and the use of those assets in the most commercially efficient manner possible. I for one would gladly had bid for such shipping if it had been offered by public tender. However, the surreptious largesse of 14 ships to a Prince du sang from a President supposed to be in caretaker mode does raise alarms as to the cupidity which we might expect unless there are the proper checks and balances contained in the Constitution to stamp out corruption.

In the expectation that the new regime will recognize and reward your untiring efforts, I would ask that, as a friend devoted to fiscal and moral rectitude, you investigate this transaction further and take the appropriate judicial and remedial steps to restore public confidence in the accountability of the Government under its new master.

Finally, I and the Grand Sanhedrin have been considering a proposal to promote the French cause amongst our brethren in Algeria. The local Jewish population has been most helpful as guides and suppliers to the French Army in their struggle against the local insurgents. We feel that by providing schools to educate our brethren in our ways, the Jewish people may become servants of France and maybe one day, citizens of our fair Nation. Given your elevation contrary to my position in opposition, I would appreciate your advocacy and sponsorship of this proposal in the Government which is to come.

Please visit when you return to Paris for the constitutional debates. Betty and I would love to dine with you and your wife, and reminisce over those glorious days of our youth .

I remain, dear Sir, your devoted friend,

Jacques de Rothschild