Not Fade Away

A Breton AAR for Magna Mundi Gold 2

A Breton AAR for Magna Mundi Gold 2

Chapter I -- 1453: Out of the Muck

Chapter II – 1459: The Artist Unearthed

Chapter III -- 1460: Going Dutch

Chapter IV – 1473: Night Ride Through Zeeland

Chapter V – 1482: Francois to Francois

Chapter VI – 1487: Up the Loire

Chapter VII – 1492: Passing the Mantle

Chapter VIII – 1500: Lady in Waiting

Chapter IX – 1500: Empire Ascendant

(Interlude: the world Circa 1504)

Chapter X – 1504: Authority and Affirmation

Chapter XI – 1510: Rebellions

Chapter XII – 1512: Help from Holland

Chapter XIII – 1514: Enter Jean

Chapter XIV – 1516: Truths from Abroad

Chapter XV – 1516: In the Hall of Kings

Chapter XVI – 1520: Will and Estates

Chapter XVII – 1521: Strike the Nail

Chapter XVIII – 1523: Eyes on the Horizon

Chapter XIX – 1525: The Edict of Nantes

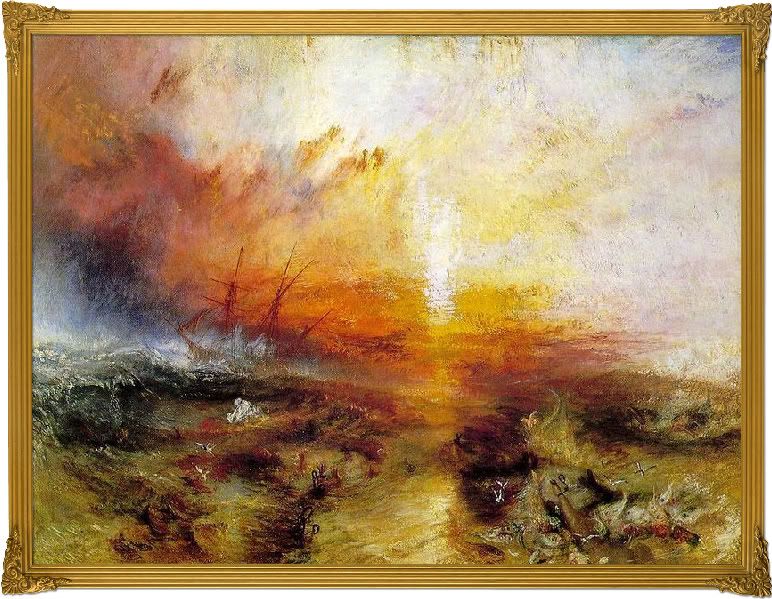

Chapter XX – 1527: Upon this Dock

Chapter XXI – 1529: Lessons Learned

Chapter XXII – 1531: Writing of Rights

Chapter II – 1459: The Artist Unearthed

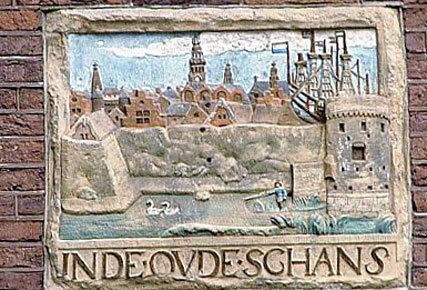

Chapter III -- 1460: Going Dutch

Chapter IV – 1473: Night Ride Through Zeeland

Chapter V – 1482: Francois to Francois

Chapter VI – 1487: Up the Loire

Chapter VII – 1492: Passing the Mantle

Chapter VIII – 1500: Lady in Waiting

Chapter IX – 1500: Empire Ascendant

(Interlude: the world Circa 1504)

Chapter X – 1504: Authority and Affirmation

Chapter XI – 1510: Rebellions

Chapter XII – 1512: Help from Holland

Chapter XIII – 1514: Enter Jean

Chapter XIV – 1516: Truths from Abroad

Chapter XV – 1516: In the Hall of Kings

Chapter XVI – 1520: Will and Estates

Chapter XVII – 1521: Strike the Nail

Chapter XVIII – 1523: Eyes on the Horizon

Chapter XIX – 1525: The Edict of Nantes

Chapter XX – 1527: Upon this Dock

Chapter XXI – 1529: Lessons Learned

Chapter XXII – 1531: Writing of Rights

Introduction:

Welcome to my first AAR! I can say it’s been a thrill to write and some painstaking work has gone into it. It’s not really a ‘gameplay blog’… mostly in character, but I’ve tried to keep the dialogue as naturalistic as possible.

I think I should give a bit of background for the reader on two things: one, the nature of the Magna Mundi mod (which many of you do know) and two, that little blip of purplish country which is so often absorbed into France by 1500…

Magna Mundi Gold 2 is the extraordinary mod that, in my view, tries to leave the game with a genuine ‘sandbox’ feel, but at the same time, takes away many of the lurid, ahistoric options that vanilla EU3 gives the powergamer. The pace of change in this game is much more in line with real history; the HRE is not gobbled up piecemeal, but a viable entity, etc. etc. There are far more changes than I can sufficiently cover, but suffice it to say, I will not play ‘vanilla EU3’ again until In Nomine comes out, and likely even then I will stick to MM. Check It Out! I’ve tried to highlight some of the nifty things MM ‘does right’ at times in the Gameplay Notes. Nevertheless, if you want to read an AAR where a tiny country bends the whole bloody world to her will, this is not the AAR for you.

As for Brittany: In this era, the Breton people are NOT FRENCH. Their language was closer to Irish than French, their traditions were wholly different as well. The country’s English name was Brittany, the French name Bretagne, the Breton name, Breizh. (Any time you see a word in the AAR with odd Zs, Ks and Hs, you can bet it’s ‘real’ Breton.) The Dukes of Brittany had a colorful role in history leading up to 1450; there were often close ties with the Scots royals and England as well, but the Bretons were also NOT the Normans, who conquered England, and who by 1453 were pretty well-assimilated into “French” culture.

The westerly Breton provinces, Finistere and Morbihan, are the most “non-French”… however, the Breton dukes also controlled Armor, which had many French influences, and Rennes, the nation’s ‘second city.’ Furthermore, the Vendee, to the south, at the mouth of the mighty Loire, is actually culturally more “Cosmopolitaine” French than Breton, and it’s also home to the Dukes; Nantes is not only the seat of power but the richest city as well.

France was certainly well on her way to ‘great power’ status in 1453, but Bretagne had real ambitions of remaining an independent power. The French aggressively pursued an annexation-by-marriage policy; In reality, the French invaded with Swiss mercenaries by 1517 or so to annul Anne II’s marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor, and force her to marry into the French crown. The independent-minded country was no more.

Last edited: