It had to happen sometimes, but at least the Portuguese have been sent back. Alas that they have enabled a far more insidious invasion.

Huēhuehcāyōmatiliztli Mēxihcah: A Narrative Aztec AAR

- Thread starter CollapsingHrungDisaster

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Portuguese have been seen off this time, but their hitchhiking "friends" may yet bring down Aztec hegemony all on their own. Undoubtedly the next few decades will be a time of travail, and few will live to see the end of it.

Just as Aztec power seems consolidated and unchallenged after throwing the Portuguese back into the sea, their unknown allies strike. The next years won't be easy, even with a diplomatic Tlatoani, especially with the best general's death.

Good that you won the war before disease hit. It'd be far harder if this had gone the other way round.

Good that you won the war before disease hit. It'd be far harder if this had gone the other way round.

You say that... check the timestamps on the last 3 pictures

Chapter 7: The Great Unifier (1548-66)

Tenochtitlan, 1548. It has been nearly ten years since the epidemics came to the lands of the Aztec.

It wasn’t just smallpox. With the influx of European armies, and their settlements up the coast, came a whole host of diseases that the native Americans had never seen before. Into these unprepared immune systems came smallpox, typhus, cholera, measles, dysentery, rubella and countless others. To many among the Aztec, it seemed as though the end of the world had come. Within five years of the first outbreaks, a full third of the population lay dead, and with them the state began to collapse. Crops were left to rot in the fields, several pochtea guilds collapsed, entire cities were abandoned by the few that remained. The canals of Tenochtitlan began to fill with bloated, scarred corpses. The people called it the cocoliztli- the great pestilence.

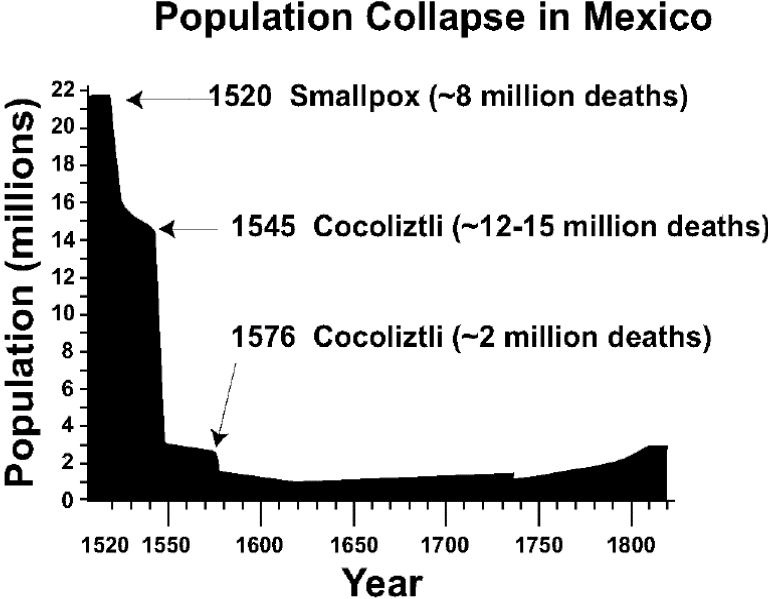

Just to show that I'm not exaggerating, here's what colonisation did to the Aztecs in the real world. The exact nature of the cocoliztli is still debated, as is the extent to which it was fuelled by persecution of the natives by colonists, but the scale of destruction it wrought is frankly insane.

The church in particular was thrown into turmoil: this were no earthquakes, the calendar was not at the end of its cycle, there was a decade to go before the next New Fire ceremony, but how could this not be the end of the world? How much more clearly could the gods show that they had forsaken their people since the coming of the caxtiltecatl? Some said that the pale men must be incarnations of the gods, and that the emperor had been wrong to fight them, whilst others said that the caxtiltecatl had been sent as the gods’ punishment- but none could say why this abandonment had happened now, after so many years of prosperity. Tens of thousands were sacrificed to try and appease Huitzilopochtli, to end the suffering, but it was all for nought… and then the priests started to succumb too. Soon, leadership within the Nahuatl church was completely nonexistent. Even as one epidemic came to an end, another part of the empire would begin to succumb, and the population decline has continued.

But with the nation teetering on the brink of annihilation, one man stayed strong: Ohimalpopoca. The now middle-aged Emperor had been an early victim of the pestilence, but was nursed back to health before the cream of the Aztec medical classes began to die in their droves. He has needed every ounce of his diplomatic nous, calling on every system of the state left functioning to try and keep the realm together. The remaining pochtea guilds have been brought fully under state control, their representatives scurrying across the land to feed the hungry information network. They and the servants of local tlatoani have taken on the distribution of food and water, disposal of the dead, even policing the doctrine of local priests. Those whose preaching is considered too doomsaying and defeatist are summarily “disappeared”, and their bodies thrown into the mass graves. Ohimalpopoca is adamant: he will not let this be the end of his forefathers’ realm.

But he is thinking bigger than mere survival. Even now, more than 5 years on, Ohimalpopoca misses Axayacatl, and remembers his warnings about the foreign invaders. There is no doubt in the emperor’s mind that the cocoliztli is their doing, a cowardly attempt to defeat his nation by men who could not do so honourably. And now, with news of the caxtiltecatl expanding their colonies in the Caribbean into the northern coasts, Ohimalpopoca has a dream. A dream of Mesoamerica united against the pale men, one nation that can put aside the infighting of decades past and throw the newcomers back into the sea. One nation under Aztec rule, from the northern highlands to the distant Maya jungles. This shall be his legacy.

Teotihuacan, 1552. Ohimalpopoca has not been able to stop the population decline of his realm, but the worst ravages of the cocoliztli are by now over. The unification project has also seen some success. The Emperor’s careful statecraft and honeyed words have started to breed a kind of proto-nationalistic, anti-European sense of unity among his lands, and the fear of more cities rebelling like those in the last war has not materialised. There has even been success at building bridges with Mixtec lands, so long a holdout of anti-Aztec sentiment. But in more far-flung regions, things have been more difficult.

The Totonac people to the north and Itza lands to the east have long been friends to the Aztec, and have prospered during their expansion, but they prize their independence ferociously. No matter how hard he tries, Ohimalpopoca has been unable to get them even to consider the prospect of unification, with one Totonac ruler even going so far as to say that “the gold of Totonacapan does not belong in Mexica coffers”. With news coming in of further Portuguese colonisation to north, Ohimalpopoca knows that he cannot wait for diplomacy to work any longer. With a heavy heart, he breaks the century-old alliance, and declares war.

This is the first conflict either nation has fought since the start of the cocoliztli, and neither are in great shape to fight it. Ohimalpopoca knows that the fragile political stability he has wrought, not to mention what’s left of the economy, can scarcely take half a million soldiers spending the next year fighting: so instead, he takes only a small force consisting mostly of the elite cuāuhocēlōtl (eagle and jaguar warriors). It’s not a traditional force either. Ohimalpopoca might hate the Europeans, but he is willing to learn a few tricks from them: horses captured during the invasion have been bred locally, allowing the Aztec to field cavalry divisions for the first time, and further experiments with iron smelting have allowed the Aztecs to develop their first practical cannons.

Some are worried at the prospect of this small, mish-mash force fighting against a numerically superior foe, but Ohimalpopoca’s experiment is a staggering success. The Totonac attempts to gather a traditionally massive Mesoamerican army devolve into chaos as the disorganised tlatoani struggle to feed their men, while the cuāuhocēlōtl take to horses like a duck to water, raiding across vast swathes of country with gay abandon. The only significant battle is fought at Tzicoac, where 90,000 advancing Totonac are routed under a hail of fire from the tlequiquiztli units, before being set upon by infantry and cavalry alike. The outnumbered Aztec win a famous victory, and the rest of the realm falls without much resistance.

Tenochtitlan, 1558. Ohimalpopoca weeps.

Another epidemic has struck the Aztec capital; typhoid, this time. It’s less destructive than previous outbreaks, but in the city’s dense streets it still kills indescriminate thousands. Last night, Ohimalpopoca’s nine year-old daughter, Matlalxoch, lost her fight with the disease, and Ohimalpopoca has joined the throngs of people walking the city streets in public grief. A dozen professional mourners, women wailing like sirens, flank the royal procession as it marches back from the funeral. For the aging emperor, now well into his fifties after witnessing a lifetime of hardship for his people, it is a bitterly personal blow.

As they pass the Huēyi Teōcalli, Ohimalpopoca makes out another scream over the mourners’ wails. He doesn’t need to look to identify its cause: the sharp noise, descending quickly into a quiet gurgle, can only be from another soul sent to the gods from the temple priesthood. His eyes are refilled with tears, and he looks away. Amidst all this death brought upon us by the caxtiltecatl, he thinks to himself, and still it is our blood flowing down the steps of the pyramid.

As the procession marches onwards, the sounds of the temple dies away. But that nugget of an idea remains in Ohimalpopoca’s head, and one week later he issues what will later become known as the Statement of the New Culture, or Huehuetlahtolli Yancuic.

The proclamation is far-reaching. Some of it merely cements and makes permanent several changes in the business of government that have become the norm under Ohimalpopoca: state control over agricultural distribution, the responsibilities and subservience of regional tlatoani to Tenochtitlan, and the formation of a civil service from the government-controlled aspects of the pochtea, legal system, army and other institutions. Some of it is more unexpected, such as the plan to diversify education, with fewer Aztec boys being raised as warriors in an effort to revitalise the still-struggling Aztec economy, and protect against further mayhem should the cocoliztli strike again. It even includes an olive branch to the Mixtec, granting them greater local control as part of Ohimalpopoca's continued diplomatic overtures.

But it also contains new, and unusual, instructions for the church: that the priests will no longer sacrifice the lives any who worship the gods. From now on, only heretics and Europeans may be killed.

Ohimalpopoca’s timing is particularly notable. It is almost exactly a year until the next New Fire festival, marking the end of the 52-year calendar cycle. After all that has transpired since the last one, fear that the world was about to come to a final end is already at a higher pitch than normal: now, it intensifies still further. Some among the macehualtin commit suicide rather than risk the gods’ vengeance, whilst several members of the priesthood are caught conducting sacrifices in secret and summarily executed. Only Ohimalpopoca’s status, as both the gods’ representative on earth and the all-controlling “universal spider” of the Aztec state, is able to maintain order.

The year passes. The New Fire ceremony occurs, with a captured Portuguese colonist from the northern reaches sacrificed beneath the ceremonial fire drill. And, despite the worst omens, the sun continues to rise the next morning. No earthquakes, no plagues: just the gentle warming of Huitzilopochtli. Ohimalpopoca has taken the greatest of spiritual risks, but it has paid off.

Cuilapan, 1563. Five years since the Huehuetlahtolli Yancuic, and the sun is continuing to rise each day. Indeed, it seems that the gods representative on earth has heard the divine call well: the epidemics have begun to peter out, agricultural output is going through a positive resurgence, and the population has begun to stabilise. But more immediately, Ohimalpopoca has won another victory in his greatest ambition: unification.

To assuage the continued ravings of the more militaristic factions within his realm, Ohimalpopoca has renewed his attempts to unite his lands by force rather than diplomacy. An invasion of the Cocomes lands in the Yucutan came first, and was swift and decisive. The Aztec army might be a shadow of its former size at around 25,000 men, but the assumption of more unified state control has allowed for a rapid development in tactics and technology to take place. The Aztec use of cannonfire and cavalry repeatedly shatters the Mayan armies but so does a novel infantry strategy. Under Ohimalpopoca’s son, general Tizoc, men within a unit are encouraged to fight in a close formation, assisting one another in defense and offense with their larger-than-usual chimalli shields and widely-deployed ichcahuipilli armour. The Cocomes hordes are barely able to make a dent in these new units, and their defeat was total. Prophesies of Aztec military doom, it seems, are premature.

That left only the Itza as the last Mesoamerican state not under Aztec control: and today, word comes back from the eastern army. Itza forces have been utterly defeated in the field, and now Ohimalpopoca in the undisputed master of the Americas. Mexica or Zapotec, Totonac or Tarascan, Nahua or Mayan: now, they are all Aztec. And, with colonisation efforts expanding to both the north and south, the Aztec demesne is only growing.

But Ohimalpopoca does not have long to enjoy his newfound stature. Eighteen months after the Itza surrender, Queen Centehua dies suddenly after a short illness. The Emperor is heartbroken, and suddenly it is as if the toll of three decades on the throne have hit him all at once. Eight months later, in January of 1566, his heart gives out.

The realm mourns the loss of its Huey Tlatoani. Ohimalpopoca presided over perhaps the greatest crises and changes in Aztec society since the founding of Tenochtitlan, and somehow emerged with a nation battered, but whole. The great unifier stands ruler of all Mesoamerica, but there is one last great foe for the new emperor Tizoc, to contend with. Along the northern coastline, Portuguese colonists have carved out a little state of their own in the dusty Chichimec drylands. A clash of empires is brewing.

Attachments

Last edited:

He has navigated the Aztec state through its greatest challenge, and made it as strong as he could. These are no mean achievements.

The Aztecs may not be entirely out of the woods yet, but at the very least they seem to have weathered the worst of the storm. There will undoubtedly be a reckoning with the Portuguese invaders coming soon.

It's been a few weeks, what with work and whatnot, but Aztec glory shall continue ever forwards!

(My inconsistent screenshot-taking is back for this one as well, my apologies)

Tenochtitlan, 1568. From the ancient metropolis of his forefathers, Ohimalpopoca’s son, the 31 year-old Tizoc Acamapichtli, reigns supreme. Tizoc is a dynamic figure, an energetic man who throws himself at every aspect of rulership like a dog to a bone. And, a decade after the Huehuetlahtolli Yancuic, the promised “New Culture” appears to be coming to fruition under his leadership. With the ravages of the cocoliztli now past, the population has started to tentatively grow again (though the streets are still littered with empty houses), and this growth is compounded by a wealth of technological innovations gleaned from the caxtiltecatl. After years of exposure, the secrets to mining, gunpowder, ocean shipbuilding, glassware and many more have trickled from the Europeans to the Aztecs, completely transforming the local economy. The Europeans have even changed the Nahuatl language: exposure to paper, and especially the printing press, has drastically increased the importance of written literacy, while scribes and printers have begun to employ a “reduced” form of written Nahuatl using fewer logograms and more syllabic notation (allowing movable type to be better deployed). Out of the chaos of the cocoliztli and European colonisation, the Aztec state has undergone a revolution.

But Tizoc sees the Europeans as more an opportunity in more ways than one. Rebuffed from the Mexican interior, the Portuguese have begun settlement in the Chichimec lands to the north, and now their colonies rule a four hundred mile-long stretch of coastline. It is from watching these northern settlers, and their struggle for self-sufficiency and wealth acquisition, that Tizoc has been able to make the most technological progress- but watching from afar can only teach so much. Tizoc calls his banners, and 30,000 Aztecs march north.

The war is brief and conclusive. Isolated from their colonial masters, the settlers are barely able to muster a response of their own; and after the first couple of settlements are burned down, the rest are reluctant to follow suit. The colonists reluctantly bend the knee, and Tizoc packs every Portuguese vessel he can find with booty and captives, before sending them south.

Tenochtitlan, 1569. Flush with success after his conquests. Tizoc’s attempts to expand his realm have continued. His latest conquests to the north are now home to Aztec military training camps, in an effort to keep local unrest in check, and he is also attempting to beat the caxtiltecatl at their own game by funding colonization efforts towards the south. His aim is to secure an Aztec foothold down towards Nicaragua and prevent further Portuguese settlement. And so, in 1469, he gives the fateful order to start a colony in Tologalpa, on the Mosquito coast.

Initially, nothing seems remarkable about this instruction, but two events conspire to ensure that it will echo down in history. Firstly, in September of 1470, Tizoc dies suddenly, after a brief illness, and his son Tlacotzi ascends to the throne. Which is a slight problem, since Tlacotzi is just 13 months old.

The second event comes in 1572, when news comes up from Mosquito. They have found gold.

Lots of gold.

Paris, 1574. King Henri stares at a map spread out on the table in front of him. It’s the latest offering from French colonists in Colombia, describing the new lands in which they have settled. The broad sweep of the coast stretches from east to west, with French lands carving deep into the heart of the continent. Already, French territories in the new world cover almost half the land area of France herself… but that isn’t where Henri is looking. Instead, he’s looking up at the eastward part of the map, to where the land twists northwards and details of the coastline begin to be replaced by the cartographer’s imagination. Across this great sweep of land is marked a single word: Aztec.

Henri strokes his beard. With his left hand, he reaches out and taps the ill-defined squiggle of coast off to the south of Aztec lands that the settlers call Miskito, or Mosquito. His head turns, and scans another sheet of paper- a letter from the Portuguese ambassador. From their base in Rio La Plata, the Portuguese have been making their own settlement in Nicaragua via the Pacific coast, and they have heard the news of fresh gold reserves in the region. Now, the news has reached Europe, and the French king is intrigued.

The implication of the ambassador’s letter is not lost on him. King Carlos of Portugal has learned the lessons of his father Alfonso; that you underestimates the Aztec strength of arms at your own peril. These native savages are organised, and will require more than a handful of conquistadors to put down. Moreover, the Mosquito coast is only a few days’ travel from French Colombia by sea, and a few weeks’ by land. King Carlos is making Henri an offer: the gold of Mosquito, in exchange for my colonies back.

It is a good offer.

King Henri raises a hand- a manservant is by his side in an instant. “Fetch me my scribe, I have a letter to dictate. And get someone to send word to de Bethune… I may have a job for him.

Uaymil, 1575. An Aztec trading vessel staggers into port. Her sails are in rags, her hull is covered in shattered spars, and her crew are sporting a lurid selection of injuries. His arm in a sling, he stumbles ashore, and begins his garbled story: his ship, along with two others, attacked by a caravel bearing Portuguese colours. Over the coming days, more stories trickle in of French and Portuguese ships alike hunting along the Caribbean coast. It doesn’t take long for the pochtea to carry news back to Tenochtitlan: the war has begun.

Empress Centehua, Tlacotzi’s mother and regent, reacts as best she can. She immediately places Cuitlahuac Itzcoatl, one of her late husband’s most trusted generals, in complete command of the military response, and he begins by marshalling his forces in Nicaragua. He burns Portuguese settlements in the area, preventing them from establishing an easy beachhead, but in February the news turns sour.

Portuguese colonists to the north, buoyed by news of the mother country coming to their aid, raise their flag in revolt of Aztec rule. Cuitlahuac splits off a detachment of his forty thousand-strong army to quell the unrest before it matures into a fully-fledged rebellion- but then, reports come in of a huge French fleet off the Nicaraguan coast, including multiple troop transports. Before he knows it, thirty thousand Frenchmen are disembarking near the Kukalaya river.

Cuitlahuac cannot risk further reinforcements arriving, and hits the French hard and fast with the forces he can muster. The Battle of Kukalaya is bloody; the French have the numbers and firepower, in the form of 17 artillery pieces, but they are disorganised and in foreign lands. The Aztec lose five thousand men to cannonfire before breaking the French defensive line- the French repeat, but General Aurelien de Bethune is able to command an organised retreat (with his artillery). When further news comes in of a Portuguese landing to the north, Cuitlahuac calls off the chase, and the French are able to march back eastwards to safety. Thankfully, repelling the Portuguese landing proves much easier.

Tologalpa, 1576. de Bethune isn’t gone for long. By October, he is back in Nicaragua, with twenty-five thousand men at his back, and more Portuguese arriving by sea. Cuitlahuac is torn. The numbers are fairly even, and he desperately wants to prevent the caxtiltecatl from gaining a beachhead, but he is wary of trying to fight the Europeans on their own terms. The conundrum is still bothering him when news arrives from the north: Queen Centehua is dead, apparently from bowel cancer. Cuitlahuac isn’t about to give battle with omens like that knocking about. He orders his troops to pull back, effectively ceding Nicaragua to the Europeans.

Nine months later, the situation has only got worse. The rebels to the north have been crushed, but now there are more than fifty thousand caxtiltecatl roaming around Guatemala. Cuitlahuac marches south: with the French sieging the new fort at Q’umarkaj, he plans to strike hard at the Portuguese forces while the two are separated. If he can win a decisive victory, he stands a chance to either drive the invaders back or catch the French army outnumbered at Q’umarkaj. He advances east, and the die is cast.

Cuitlahuac finds the Portuguese forces waiting for him near the old Itza city of Chacujal, their lines drawn up into a defensive position. He begins an artillery bombardment, and at the same time orders his cavalry to begin harassing the Portuguese position, trying to break up their formation. When this fails, he orders his infantry forward, and the two lines clash in a hail of gunpowder smoke. The Aztec have the numbers, and begin to steadily push the Portuguese line back- but then another, unfamiliar bugle horn splits the air amidst the roar of battle. Cuitlahuac’s blood runs cold. The French have arrived.

General de Bethune has timed his gambit to perfection. With the Aztec fully engaged, he orders his men forward, and hails of withering musket fire rake into the exposed flanks of the Aztec line. The French cavalry, meanwhile, run riot through Aztec artillery positions, forcing them to abandon most of their guns and flee. Cuitlahuac knows that the day is lost, and gives the order to sound the retreat; but as the line pulls back, a troop of French infantry charge his position. The line gives way to brutal hand-to-hand fighting; but it has been many moons since this kind of combat was what every Aztec man lived for. Cuitlahuac Itzcoatl holds his position for several minutes, before a French sword takes him through the gut.

Over 13000 Aztecs are killed at the Battle of Chacujal, to just 3000 European, and these are losses that the Aztec can ill-afford to replace. Outnumbered, shattered, and with all their major leaders now dead, it is not long before the Aztec sue for peace.

Terms are remarkably generous- the war has been longer and more costly than King Henri originally expected, and he is warm to the idea of peace (though de Bethune is furious at not being given the opportunity to eviscerate the natives still further). The Aztec are allowed to maintain control over the coastal Portuguese settlements- but they are still forced to give up all of their holdings south of Honduras, and pay the French more than fifteen thousand pounds of silver. For a nation that had so recently thought itself destined for new greatness, it is a bitter pill to swallow. Beyond the reaches of Mesoamerica, there is a whole new world of power and majesty- and now it has come knocking.

(My inconsistent screenshot-taking is back for this one as well, my apologies)

Chapter 8: The Empires Strike Back (1568-78)

Tenochtitlan, 1568. From the ancient metropolis of his forefathers, Ohimalpopoca’s son, the 31 year-old Tizoc Acamapichtli, reigns supreme. Tizoc is a dynamic figure, an energetic man who throws himself at every aspect of rulership like a dog to a bone. And, a decade after the Huehuetlahtolli Yancuic, the promised “New Culture” appears to be coming to fruition under his leadership. With the ravages of the cocoliztli now past, the population has started to tentatively grow again (though the streets are still littered with empty houses), and this growth is compounded by a wealth of technological innovations gleaned from the caxtiltecatl. After years of exposure, the secrets to mining, gunpowder, ocean shipbuilding, glassware and many more have trickled from the Europeans to the Aztecs, completely transforming the local economy. The Europeans have even changed the Nahuatl language: exposure to paper, and especially the printing press, has drastically increased the importance of written literacy, while scribes and printers have begun to employ a “reduced” form of written Nahuatl using fewer logograms and more syllabic notation (allowing movable type to be better deployed). Out of the chaos of the cocoliztli and European colonisation, the Aztec state has undergone a revolution.

But Tizoc sees the Europeans as more an opportunity in more ways than one. Rebuffed from the Mexican interior, the Portuguese have begun settlement in the Chichimec lands to the north, and now their colonies rule a four hundred mile-long stretch of coastline. It is from watching these northern settlers, and their struggle for self-sufficiency and wealth acquisition, that Tizoc has been able to make the most technological progress- but watching from afar can only teach so much. Tizoc calls his banners, and 30,000 Aztecs march north.

The war is brief and conclusive. Isolated from their colonial masters, the settlers are barely able to muster a response of their own; and after the first couple of settlements are burned down, the rest are reluctant to follow suit. The colonists reluctantly bend the knee, and Tizoc packs every Portuguese vessel he can find with booty and captives, before sending them south.

Tenochtitlan, 1569. Flush with success after his conquests. Tizoc’s attempts to expand his realm have continued. His latest conquests to the north are now home to Aztec military training camps, in an effort to keep local unrest in check, and he is also attempting to beat the caxtiltecatl at their own game by funding colonization efforts towards the south. His aim is to secure an Aztec foothold down towards Nicaragua and prevent further Portuguese settlement. And so, in 1469, he gives the fateful order to start a colony in Tologalpa, on the Mosquito coast.

Initially, nothing seems remarkable about this instruction, but two events conspire to ensure that it will echo down in history. Firstly, in September of 1470, Tizoc dies suddenly, after a brief illness, and his son Tlacotzi ascends to the throne. Which is a slight problem, since Tlacotzi is just 13 months old.

The second event comes in 1572, when news comes up from Mosquito. They have found gold.

Lots of gold.

Paris, 1574. King Henri stares at a map spread out on the table in front of him. It’s the latest offering from French colonists in Colombia, describing the new lands in which they have settled. The broad sweep of the coast stretches from east to west, with French lands carving deep into the heart of the continent. Already, French territories in the new world cover almost half the land area of France herself… but that isn’t where Henri is looking. Instead, he’s looking up at the eastward part of the map, to where the land twists northwards and details of the coastline begin to be replaced by the cartographer’s imagination. Across this great sweep of land is marked a single word: Aztec.

Henri strokes his beard. With his left hand, he reaches out and taps the ill-defined squiggle of coast off to the south of Aztec lands that the settlers call Miskito, or Mosquito. His head turns, and scans another sheet of paper- a letter from the Portuguese ambassador. From their base in Rio La Plata, the Portuguese have been making their own settlement in Nicaragua via the Pacific coast, and they have heard the news of fresh gold reserves in the region. Now, the news has reached Europe, and the French king is intrigued.

The implication of the ambassador’s letter is not lost on him. King Carlos of Portugal has learned the lessons of his father Alfonso; that you underestimates the Aztec strength of arms at your own peril. These native savages are organised, and will require more than a handful of conquistadors to put down. Moreover, the Mosquito coast is only a few days’ travel from French Colombia by sea, and a few weeks’ by land. King Carlos is making Henri an offer: the gold of Mosquito, in exchange for my colonies back.

It is a good offer.

King Henri raises a hand- a manservant is by his side in an instant. “Fetch me my scribe, I have a letter to dictate. And get someone to send word to de Bethune… I may have a job for him.

Uaymil, 1575. An Aztec trading vessel staggers into port. Her sails are in rags, her hull is covered in shattered spars, and her crew are sporting a lurid selection of injuries. His arm in a sling, he stumbles ashore, and begins his garbled story: his ship, along with two others, attacked by a caravel bearing Portuguese colours. Over the coming days, more stories trickle in of French and Portuguese ships alike hunting along the Caribbean coast. It doesn’t take long for the pochtea to carry news back to Tenochtitlan: the war has begun.

Empress Centehua, Tlacotzi’s mother and regent, reacts as best she can. She immediately places Cuitlahuac Itzcoatl, one of her late husband’s most trusted generals, in complete command of the military response, and he begins by marshalling his forces in Nicaragua. He burns Portuguese settlements in the area, preventing them from establishing an easy beachhead, but in February the news turns sour.

Portuguese colonists to the north, buoyed by news of the mother country coming to their aid, raise their flag in revolt of Aztec rule. Cuitlahuac splits off a detachment of his forty thousand-strong army to quell the unrest before it matures into a fully-fledged rebellion- but then, reports come in of a huge French fleet off the Nicaraguan coast, including multiple troop transports. Before he knows it, thirty thousand Frenchmen are disembarking near the Kukalaya river.

Cuitlahuac cannot risk further reinforcements arriving, and hits the French hard and fast with the forces he can muster. The Battle of Kukalaya is bloody; the French have the numbers and firepower, in the form of 17 artillery pieces, but they are disorganised and in foreign lands. The Aztec lose five thousand men to cannonfire before breaking the French defensive line- the French repeat, but General Aurelien de Bethune is able to command an organised retreat (with his artillery). When further news comes in of a Portuguese landing to the north, Cuitlahuac calls off the chase, and the French are able to march back eastwards to safety. Thankfully, repelling the Portuguese landing proves much easier.

Tologalpa, 1576. de Bethune isn’t gone for long. By October, he is back in Nicaragua, with twenty-five thousand men at his back, and more Portuguese arriving by sea. Cuitlahuac is torn. The numbers are fairly even, and he desperately wants to prevent the caxtiltecatl from gaining a beachhead, but he is wary of trying to fight the Europeans on their own terms. The conundrum is still bothering him when news arrives from the north: Queen Centehua is dead, apparently from bowel cancer. Cuitlahuac isn’t about to give battle with omens like that knocking about. He orders his troops to pull back, effectively ceding Nicaragua to the Europeans.

Nine months later, the situation has only got worse. The rebels to the north have been crushed, but now there are more than fifty thousand caxtiltecatl roaming around Guatemala. Cuitlahuac marches south: with the French sieging the new fort at Q’umarkaj, he plans to strike hard at the Portuguese forces while the two are separated. If he can win a decisive victory, he stands a chance to either drive the invaders back or catch the French army outnumbered at Q’umarkaj. He advances east, and the die is cast.

Cuitlahuac finds the Portuguese forces waiting for him near the old Itza city of Chacujal, their lines drawn up into a defensive position. He begins an artillery bombardment, and at the same time orders his cavalry to begin harassing the Portuguese position, trying to break up their formation. When this fails, he orders his infantry forward, and the two lines clash in a hail of gunpowder smoke. The Aztec have the numbers, and begin to steadily push the Portuguese line back- but then another, unfamiliar bugle horn splits the air amidst the roar of battle. Cuitlahuac’s blood runs cold. The French have arrived.

General de Bethune has timed his gambit to perfection. With the Aztec fully engaged, he orders his men forward, and hails of withering musket fire rake into the exposed flanks of the Aztec line. The French cavalry, meanwhile, run riot through Aztec artillery positions, forcing them to abandon most of their guns and flee. Cuitlahuac knows that the day is lost, and gives the order to sound the retreat; but as the line pulls back, a troop of French infantry charge his position. The line gives way to brutal hand-to-hand fighting; but it has been many moons since this kind of combat was what every Aztec man lived for. Cuitlahuac Itzcoatl holds his position for several minutes, before a French sword takes him through the gut.

Over 13000 Aztecs are killed at the Battle of Chacujal, to just 3000 European, and these are losses that the Aztec can ill-afford to replace. Outnumbered, shattered, and with all their major leaders now dead, it is not long before the Aztec sue for peace.

Terms are remarkably generous- the war has been longer and more costly than King Henri originally expected, and he is warm to the idea of peace (though de Bethune is furious at not being given the opportunity to eviscerate the natives still further). The Aztec are allowed to maintain control over the coastal Portuguese settlements- but they are still forced to give up all of their holdings south of Honduras, and pay the French more than fifteen thousand pounds of silver. For a nation that had so recently thought itself destined for new greatness, it is a bitter pill to swallow. Beyond the reaches of Mesoamerica, there is a whole new world of power and majesty- and now it has come knocking.

Sometimes you have to know when to fold, but a bitter comfort that is.

And now these darned Europeans will have a taste for it.

And now these darned Europeans will have a taste for it.

It was perhaps expected that eventually the Aztecs would be overmatched by the European invaders, but it doesn't make the taste of defeat any more palatable. Nevertheless, the Aztecs have averted a total collapse at the cost of only a small portion of their periphery -- and they have undoubtedly learned a valuable lesson about the scope of the enemy they now face across the sea.

Still no sign of the Spanish though? Maybe you could try and seek a European alliance or something?

New year, new world, new Aztecs...

Chapter 9: The Voyages of Captain Popopoyotl (1578-84)

Xocoyol Popopoyotl* was six years old when he first saw the sea.

It was a bright day towards the end of the dry season, in the year 1557. Young Xocoyol’s father was travelling on business, and brought his family from their home town of Xculoc, in the Yucatan interior, to the port at Can Pech. As the sun was descending westward, their small party made their way over the final hill. The port lay spread out before them: and what a sight it was. The temple pyramid cast long shadows over the town amid the orange glow of the setting sun. Even at this distance, faint sounds of city bustle echoed up towards them- from the marketplace, homes and the docks. But it was in this harbour that the greatest view appeared. A European-made caravel sat by the shore, its fifty-foot bulk and tall masts towering over the surrounding buildings and fishing canoes like trees over grass. Sailors crawled like ants over its surface, as the ship gently rocked amid the lapping waves. And behind it lay the sea- shining like liquid gold in the evening light, the vessel seeming like a drop of obsidian upon it, the ocean seeming to extend away forever into the distance. Xocoyol had never seen so much water in his life before. It seemed gifted from the gods themselves.

As he grew into a young man Xocoyol joined other nobly-born young men local calmecac school. There he might have stayed, a minor regional noble of no lasting importance- but then he decided to train as a judge, which meant travelling to Tenochtitlan to continue his education. He arrived in 1572, aged 21, but after only a little time he dropped out of his legal education and joined the imperial court. For an unproven young man from such a distant backwater to move in such circles was unusual, and drew many whispers at court, but Xocoyol’s charm won him many friends. His youthful, handsome appearance didn’t do any harm either, and rumours abounded concerning his close friendship with Empress Centehua. Especially given the death of Emperor Tizoc two years previously.

When Centehua also died in 1576, Xocoyol knew that his privileged position at court was living on borrowed time, and shortly afterwards he left court to take up arms against the French invaders. Xocoyol career as a soldier was unremarkable, but he managed to survive the Mosquito war and went back to Tenochtitlan after peace was declared two years later. He returned to a court embroiled in intrigue and infighting, with various factions vying for influence over the young huey tlatoani Tlacotzin. Xocoyol had few friends to call on here- but he had taken the time before he left to cultivate a close friendship with the boy-emperor. It was only a matter of time before jealous rivals began to scheme against him though, so Xocoyol needed to act fast. His plan was characteristically dramatic: he petitioned Tlacotzin for funding to sail across the endless ocean.

This was a… bold proposal. Xocoyol had no naval experience, and the Aztec state had no navy, relying only on canoes and small fishing boats. Their only contact with oceangoing vessels had come from European invaders and occasional Caribbean traders. Beyond that, nobody at court had any real expectation of what he might find; while all agreed that the white men must have come from somewhere, nobody could agree how far away it It was, or what Xocoyol might find. Many wondered allowed what the young fool hoped to achieve even if he did discover something, whilst others skipped the subtlety and laughed in his face. It almost unthinkable that he could put together a crew, much less supply and execute a voyage across the sea.

But Xocoyol had some tricks up his sleeve. His childhood fascination with the sea had never gone away, and he had first had the idea of going to explore it in Centehua’s day. During his soldiering days, suppressing rebels to the north, he had visited the ports of the Aztec-controlled colonial towns, where some shipwrights still worked on repairs to traders’ vessels and knew how they were constructed. He had also met men both white and Aztec who had experience of sailing with traders and smugglers, and who knew the waters of the Caribbean. The ocean was a lot less unknown to him and his people than first it seemed.

Eventually, his charisma won out; he was given enough funds to refit a trio of old smuggler’s vessels, and provide for the journey. Most of the court were glad to see the back of him- but now, captain Popopoyotl had free reign to sail the ocean seas. Bravely, he pointed his ship eastwards, and set out across the Atlantic.

The next three months were among the worst of Popopoyotl’s life. No sooner had he recovered from violent seasickness than their vessels ran into bad weather once past the Bahamas. His flagship, the Miztli (Puma), was wracked by the storms, wind and water screaming through the rigging. Two men were drowned and a crate of supplies lost before the storm passed, and then they spent five days becalmed in horse latitudes. But eventually, in January, the Miztli sighted Lisbon. Captain Popopoyotl had done it.

They did not stay long in Lisbon. Xocoyol feared that some of his men would attempt to flee at the sight of their home country, and only let a few trusted native-born Aztecs go ashore to resupply. But he could not resist taking a look himself, and wandered round the Portuguese capital open-mouthed. The city was small and disorganised compared to the canals of Tenochtitlan, but his breath was still taken away by the towering vaulted ceilings at the Cathedral of Saint Mary, and the mighty cannons atop Belém Tower. And that was only the start of his voyage.

For the next two years, Xocoyol explored everything that western Europe had to offer him. He drank wine in Bordeaux, cider in Munster and whiskey in Speyside. He ate snails in Paris, whale in Norway and shark fin soup in Greenland. Though he rarely stopped for long, he even sailed up the Thames and presented himself at the court of King George for a short time. When he finally returned to America in 1581, many had given him up for lost- but he returned with maps, a hold laden with exotic goods, and a crew pressed from five countries. There were doubts over some of his stories- few could believe tales about sea-beasts the size of pyramids, grey dogs the weight of a man and the wastelands of solid white water inhabited solely by alluring warrior-women, but Xocoyol stuck to all of them.

In 1582, he left on a second voyage, this time journeying north up the east coast of the Americas. The results were less dramatic, but still successful. More stories of frozen wastelands and fantastical beasts abounded, but so too did more familiar tales- of white men who had journeyed west to take land from those who called it home. Xocoyol’s doubters at court began to fall away, and he was showered with favours from the intrigued and delighted Tlacotzin.

But Xocoyol’s wanderlust had been piqued, and could not be withheld for long. In 1583 he set out again southwards, intrigued by stories of more Portuguese settlers at the edge of the world where the land finished. He never returned. While attempting to navigate the storm-tossed waters of the southern ocean, his faithful Miztli capsized, and captain Popopoyotl went down with her. Only one vessel from his party, manned by just sixteen men, ever made it back to Mexico.

Xocoyol’s voyages may seem insignificant in comparison to his European contemporaries, one of whom had sailed around the world before he even arrived in Lisbon. But in Aztec history, there are few figures more important. He was the father of Aztec naval ambitions, encouraging Tlacotzin to invest seriously in shipbuilding infrastructure, and paving the way for future ambitions. But Xocoyol’s crowning achievement was simply to show his countrymen that such journeys were possible, and others would follow in his footsteps. To begin with, it was just a trickle of adventurous traders, but in time that trickle would become a stream, and later a flood. Within two decades of his death, there would be Aztec ambassadors in courts across Europe, and Aztec-build carracks in Can Pech harbour. That shining-eyed young boy had changed the world.

(*yes, that was really the name the game gave me. I know, it’s amazing)

Chapter 9: The Voyages of Captain Popopoyotl (1578-84)

Xocoyol Popopoyotl* was six years old when he first saw the sea.

It was a bright day towards the end of the dry season, in the year 1557. Young Xocoyol’s father was travelling on business, and brought his family from their home town of Xculoc, in the Yucatan interior, to the port at Can Pech. As the sun was descending westward, their small party made their way over the final hill. The port lay spread out before them: and what a sight it was. The temple pyramid cast long shadows over the town amid the orange glow of the setting sun. Even at this distance, faint sounds of city bustle echoed up towards them- from the marketplace, homes and the docks. But it was in this harbour that the greatest view appeared. A European-made caravel sat by the shore, its fifty-foot bulk and tall masts towering over the surrounding buildings and fishing canoes like trees over grass. Sailors crawled like ants over its surface, as the ship gently rocked amid the lapping waves. And behind it lay the sea- shining like liquid gold in the evening light, the vessel seeming like a drop of obsidian upon it, the ocean seeming to extend away forever into the distance. Xocoyol had never seen so much water in his life before. It seemed gifted from the gods themselves.

As he grew into a young man Xocoyol joined other nobly-born young men local calmecac school. There he might have stayed, a minor regional noble of no lasting importance- but then he decided to train as a judge, which meant travelling to Tenochtitlan to continue his education. He arrived in 1572, aged 21, but after only a little time he dropped out of his legal education and joined the imperial court. For an unproven young man from such a distant backwater to move in such circles was unusual, and drew many whispers at court, but Xocoyol’s charm won him many friends. His youthful, handsome appearance didn’t do any harm either, and rumours abounded concerning his close friendship with Empress Centehua. Especially given the death of Emperor Tizoc two years previously.

When Centehua also died in 1576, Xocoyol knew that his privileged position at court was living on borrowed time, and shortly afterwards he left court to take up arms against the French invaders. Xocoyol career as a soldier was unremarkable, but he managed to survive the Mosquito war and went back to Tenochtitlan after peace was declared two years later. He returned to a court embroiled in intrigue and infighting, with various factions vying for influence over the young huey tlatoani Tlacotzin. Xocoyol had few friends to call on here- but he had taken the time before he left to cultivate a close friendship with the boy-emperor. It was only a matter of time before jealous rivals began to scheme against him though, so Xocoyol needed to act fast. His plan was characteristically dramatic: he petitioned Tlacotzin for funding to sail across the endless ocean.

This was a… bold proposal. Xocoyol had no naval experience, and the Aztec state had no navy, relying only on canoes and small fishing boats. Their only contact with oceangoing vessels had come from European invaders and occasional Caribbean traders. Beyond that, nobody at court had any real expectation of what he might find; while all agreed that the white men must have come from somewhere, nobody could agree how far away it It was, or what Xocoyol might find. Many wondered allowed what the young fool hoped to achieve even if he did discover something, whilst others skipped the subtlety and laughed in his face. It almost unthinkable that he could put together a crew, much less supply and execute a voyage across the sea.

But Xocoyol had some tricks up his sleeve. His childhood fascination with the sea had never gone away, and he had first had the idea of going to explore it in Centehua’s day. During his soldiering days, suppressing rebels to the north, he had visited the ports of the Aztec-controlled colonial towns, where some shipwrights still worked on repairs to traders’ vessels and knew how they were constructed. He had also met men both white and Aztec who had experience of sailing with traders and smugglers, and who knew the waters of the Caribbean. The ocean was a lot less unknown to him and his people than first it seemed.

Eventually, his charisma won out; he was given enough funds to refit a trio of old smuggler’s vessels, and provide for the journey. Most of the court were glad to see the back of him- but now, captain Popopoyotl had free reign to sail the ocean seas. Bravely, he pointed his ship eastwards, and set out across the Atlantic.

The next three months were among the worst of Popopoyotl’s life. No sooner had he recovered from violent seasickness than their vessels ran into bad weather once past the Bahamas. His flagship, the Miztli (Puma), was wracked by the storms, wind and water screaming through the rigging. Two men were drowned and a crate of supplies lost before the storm passed, and then they spent five days becalmed in horse latitudes. But eventually, in January, the Miztli sighted Lisbon. Captain Popopoyotl had done it.

They did not stay long in Lisbon. Xocoyol feared that some of his men would attempt to flee at the sight of their home country, and only let a few trusted native-born Aztecs go ashore to resupply. But he could not resist taking a look himself, and wandered round the Portuguese capital open-mouthed. The city was small and disorganised compared to the canals of Tenochtitlan, but his breath was still taken away by the towering vaulted ceilings at the Cathedral of Saint Mary, and the mighty cannons atop Belém Tower. And that was only the start of his voyage.

For the next two years, Xocoyol explored everything that western Europe had to offer him. He drank wine in Bordeaux, cider in Munster and whiskey in Speyside. He ate snails in Paris, whale in Norway and shark fin soup in Greenland. Though he rarely stopped for long, he even sailed up the Thames and presented himself at the court of King George for a short time. When he finally returned to America in 1581, many had given him up for lost- but he returned with maps, a hold laden with exotic goods, and a crew pressed from five countries. There were doubts over some of his stories- few could believe tales about sea-beasts the size of pyramids, grey dogs the weight of a man and the wastelands of solid white water inhabited solely by alluring warrior-women, but Xocoyol stuck to all of them.

In 1582, he left on a second voyage, this time journeying north up the east coast of the Americas. The results were less dramatic, but still successful. More stories of frozen wastelands and fantastical beasts abounded, but so too did more familiar tales- of white men who had journeyed west to take land from those who called it home. Xocoyol’s doubters at court began to fall away, and he was showered with favours from the intrigued and delighted Tlacotzin.

But Xocoyol’s wanderlust had been piqued, and could not be withheld for long. In 1583 he set out again southwards, intrigued by stories of more Portuguese settlers at the edge of the world where the land finished. He never returned. While attempting to navigate the storm-tossed waters of the southern ocean, his faithful Miztli capsized, and captain Popopoyotl went down with her. Only one vessel from his party, manned by just sixteen men, ever made it back to Mexico.

Xocoyol’s voyages may seem insignificant in comparison to his European contemporaries, one of whom had sailed around the world before he even arrived in Lisbon. But in Aztec history, there are few figures more important. He was the father of Aztec naval ambitions, encouraging Tlacotzin to invest seriously in shipbuilding infrastructure, and paving the way for future ambitions. But Xocoyol’s crowning achievement was simply to show his countrymen that such journeys were possible, and others would follow in his footsteps. To begin with, it was just a trickle of adventurous traders, but in time that trickle would become a stream, and later a flood. Within two decades of his death, there would be Aztec ambassadors in courts across Europe, and Aztec-build carracks in Can Pech harbour. That shining-eyed young boy had changed the world.

(*yes, that was really the name the game gave me. I know, it’s amazing)

Last edited:

Still no sign of the Spanish though? Maybe you could try and seek a European alliance or something?

Now that I've done this chapter, can give this one a proper answer

Certainly a tale that will live on in song and story for centuries to come -- the Aztec discovery of the New World!

Chapter 10: By Tooth And Nail (1584-1601)

Tenochtitlan, 1584. The Aztec capital throbs with noise. The hammer of drums throbs through the streets like a racing heartbeat, the people packed into its streets and waterways throbbing with the beat, as if the city itself had come to life. The noise is loudest around the imperial palace, ascending to a deafening roar as Huey Tlatoani Tlacotzin I steps out onto the balcony, in the full regalia of imperial office. Today is his fifteenth birthday, and this event is his doing- a combination birthday party and informal coming-of-age ceremony. The tlatoani is ready to assume his full responsibilities, and he means business.

For Tlacotzin has plans. He was nine at the end of the last war- too young to understand it all, but old enough to see what the invaders wrought on his country. He saw the waves of refugees, heard the wails of countless widows, and the stories… so many stories. Men mown down like animals at Chacujal, the ancient city of Q’umarkaj reduced almost to rubble. But more than that, he remembers the face of the French ambassador, a pale-faced mouse of a man with a straggly black goatee. He remembers his patronising, self-confident smile as the peace treaty was slid across the table towards him, remembers the condescension in those pale blue eyes.

He remembers it even now, as he watches his subjects’ adoration. This, he thinks, this is true America. This land is ours. We will not be humiliated again.

Tlacotzin hates the white men. He will make them pay.

Tologalpa, 1590. Flames stream through the streets. Men, women and children flee for their lives as Aztec soldiers attack mercilessly, muskets cracking and swords flashing. Every so often, a great boom marks another stash of gunpowder going up in flames. Even the small temple, defaced from its Aztec origin and now repurposed as a Catholic church, is gutted, liquid silver flowing down the altar from where a ceremonial cross once stood. From a nearby hill, Tlacotzin watches the sack mirthlessly.

Tologalpa was the first Aztec settlement on the Mosquito coast, but the French have invested heavily in the colony since their takeover. To Tlacotzin, it is an insult to his people’s heritage. But this is no mere raid. Over the last six years, Tlacotzin has worked at a frenetic pace to modernise his kingdom, investing in technology acquisition from European colonials. He has even attempted to cut off the Europeans from further colonial expansion, launching the Chatot Expedition to establish an organised American presence in the lands west of the Florida peninsula.

But this is his biggest goal: reconquest, and expulsion.

The Second Mosquito War is neither quick nor painless. Tlacotzin sends his armies far from home, pushing deep into the Colombian interior to liberate lands recently conquered from the local Muisca tribes. The French send ten thousand of their own troops into core Aztec lands, but they are unable to maintain a foothold and are ultimately crushed at the battle of Iximche. Blood runs down the temple steps in Tenochtitlan once again.

By 1593, the Aztec and Muisca claim dominion over all of West Colombia. Tlacotzin is immediately off to continue his conquests, this time against Portuguese settlers as he strives to remove all traces of European presence from the continent. But trouble is brewing. News of the invasion is making its way across the Atlantic, and King Henri is not about to take the loss of a colony lying down.

Toliman, 1594. In a small town to the far west of Aztec lands, buried somewhere within a quiet, pochtea building, Tlactotzin Acamapichtli draws another piece of paper across the desk towards him. It’s an update from the front, and it seems the campaign against the Portuguese is going well. Far from the support of their colonial masters, the colonists have been little able to manufacture any meaningful response to the Aztec armies, and their territory is falling swiftly. Tlacotzin ponderously surveys the brief missive, nods, pushes it aside, picks up the next letter and begins reading.

A minute later, Tlacotzin’s dozing guards are startled into conciousness by an almighty shout from within the tlatoani’s chamber. Bursting inside, they find a scene of chaos. The emperor’s desk has been flung across the room, along with his chair, leaving a shower of paper in the age. The emperor himself seems unhurt- but then the guards catch glimpse of his eyes. A stare of pure, unadulterated rage bores into them from the tlatoani’s deep brown pools, quailing even these veteran soldiers before it. When he speaks, it is in a voice dripping with venom.

“Call back the armies. The caxtiltecatl have launched ships. de Bethune is coming.”

As he stalks from the ruined office, one of the guards remains frozen in place for a mere moment. He fought in the last war, and the name of de Bethune carries more terror for him than a thousand hungry jaguars.

Honduras, 1594. Tlacotzin has moved quickly. Since that day in Toliman, he and the army have been marching southwards towards Mosquito almost without rest, and not a moment too soon. He has barely been in the area a week before news comes of a French fleet attempting a landing up the coast, in the Caratasca lagoon. Tlacotzin marches to meet them, and five days later he has twenty thousand men formed up on a hill overlooking the landing-sight. His men outnumber the French, and their camp is largely unfortified- so Tlacotzin gives the order to advance.

The French are waiting. As Tlacotzin’s drums begin their booming beat, they are answered by another boom. The French have arrayed every cannon they can from the landing fleet to the landward side, and begin firing in earnest. The disciplined French infantry react to the artillery, and quickly form lines of their own- before long, the Aztec forces are advancing into a hailstorm of fire and lead. One cannonball flies less than five metres past Tlacotzin’s right shoulder, decapitating an unfortunate nahuatialli. For a moment, shock flashes across Tlacotzin’s features- but he recovers, and calmly gives the order to charge.

The initial volley robbed the Aztec charge of momentum, and early losses are terrible as the front lines wither under the speed of the French musketfire. But Aztec numbers are telling. A group of cavalrymen cut through a gap in the French perimeter, and the scene inside the encampment rapidly descends into complete mayhem. When a troop of Aztec soldiers manage to board one of the French cannon-ships, the others weigh anchor. It was close, and hugely costly, but it is a victory.

More victories follow as the French (and their Portuguese allies) are forced south out of Aztec territory- and there is even better news when Tlacotzin learns that de Bethune passed away on the voyage westward.

But it’s not all good news. The new French general, Barthelémey de Lunes, swiftly recaptures their holdings in Colombia, before marching eighteen thousand men into Honduras. Showing the same tactical nous as his predecessor, he surprises Tlacotzin’s army at the battle of Warunta River, and news is coming in of rebels and Portuguese invaders to the north.

Tlacotzin rallies his men, calls for reinforcements, and wins another stunning victory at the battle of Sula Valley to eject the French once again- but it is another close-run thing, and exceptionally bloody. Through Tlacotzin’s strength of will alone are the Aztec holding Honduras. Even has he lays siege to San Salvador, he knows that victory hangs in the balance.

Tampico, 1597. While Tlacotzin has been tied up in the south, the northern front has been a conflict of its own. The Chichimec drylands are vast, almost completely unfortified, and populated largely by native tribes and former Portuguese settlers, both of whom chafe under Aztec rule. For the past three years, the Portuguese have been in open revolt, assisted by Portuguese colonial forces, and the outnumbered provicial guardsmen are severely overstretched.

By March, what’s left of the guardsmen have gathered into a small force of around three thousand men, and make a stand against the advancing Portuguese near the port of Tampico. The Aztec take a defensive position, with the sea on one side and lagoons on one another, and it isn’t long before the two tercios collapse into an old-fashioned line fight. Powder-smoke fills the air as the two lines of pikemen scramble to find openings, but then, a strange whooping sound echoes through the roar of battle. Through the smoke there are glimpses of more men, hundreds of them in loose formation, running as if to join the Portuguese line- for a moment, the Aztec infantry start to waver, but then the newcomers raise their muskets, and launch a devastating volley into the backs of the Portuguese. The battle turns almost immediately into a rout.

The newcomers have an unlikely patron. Olintecke Quilatzli is a mestizo- a half-blood, christened Marco de la Llave by his Portuguese father before his mother, a Huastec captive, fled with her son to Aztec lands when he was seven. Like Tlacotzin, he has bred a fierce hatred towards the invaders; and in these parts, his mixed heritage and commanding rhetoric have won him many supporters among native tribesmen, fellow mestizo and even local-born ethnic Portuguese rebelling against the far-off mother country. The victory at Tampico, however, proves his crowning glory. The guardsmen shower him with praise, and the regional governor (sensing an opportunity) promotes him to nahuatialli. When he marches north, and news of his victory spreads, more men flock to his banner- and when he records yet more stunning victories against both invaders and rebels, he is widely lauded as the “saviour of the north”.

Flush with his own success, and with only token forces remaining in the area, Olintecke declares his campaign over. He and his men begin the long march south to support the siege of San Salvador… and in doing so leave the north undefended.

Cuzcatlan, 1599. Olintecke’s forces arrive to a southern front, and initially he continues his run of success. He meets with Tlacotzin and launches another campaign of surprise attacks against harrying Portuguese forces, until the city finally falls in February. It seems that the Aztec are on top of the war, and Olintecke advises Tlacotzin to make peace. But Tlacotzin is defiant. The French are not yet out of the fight, and he has yet to re-establish complete control over French Colombia- so he sticks to his guns, and pushes east in pursuit of a final victory.

But the Colombian campaign of 1600 is a disaster. Tlacotzin and Olintecke take joint command of their forces, but bicker constantly. Tlacotzin doesn’t trust the mestizo, considering him halfway to an invader himself, and their dispute comes to a head in the jungles of Panama. Their divided forces are ambushed by de Lunes, who has somehow gathered a new army of nearly 25,000. The French numbers and technological superiority are telling, and the Aztec suffer a humiliating defeat.

And now, the strain of the war on the Aztec state starts to make itself felt- there simply aren’t the men to replace the mounting losses. All of a sudden, the war switches direction. The French reoccupy the Mosquito goldmines and continue to press west, while fresh Portuguese forces run rampant across the now-undefended north. More forces are landing in Yucatan- some have even reached Tenochtitlan. Tlacotzin begins to rue his earlier rashness in not suing for peace, and Olintecke makes sure he doesn’t forget it. Only Olintecke’s charisma, and the fanatical loyalty of his men towards him, prevents Tlacotzin from having him executed for insubordination.

But, as they march back west, there is at least one thing the two men can agree on. While they still have breath in their bodies, they will not stop fighting.

Oaxaca, 1601. Portuguese general Uriel Coelho leads seven thousand men towards Molte Alban. They have been terrorising Zapotec country virtually unhindered for the last six months, along with other small armies, as part of the continued allied effort to break the Aztec back. So far, the plan shows every sign of succeeding. Portugal have made continued territorial gains, and their armies are even now threatening Tenochtitlan. Surrender cannot be far off.

His army are marching along the Oaxaca valley, and he watches the mist roll off the river in the cool of the early morning. Soon, he thinks, the sun will be up, and he pauses for a moment to breath in the fresh fog. But instead of fresh morning dew, his lungs fill with smoke- hot, burning, choking smoke. He falls to his knees, coughing furiously, and is joined by hundreds of his men. And then, another kind of smoke wafts over them- gunpowder smoke. From the far side of the river, hundreds of men lay down their pots of quicklime and pick up muskets, firing into the disorganised mass of men. Coelho orders his men back into formation, but moments later they are set upon again- this time from the other flank, as thousands upon thousands of Aztec warriors charge into them. No muskets this time- this is old-fashioned Aztec warfare, with swords and mācuahuitl. The battle turns into a massacre. Not a single Portuguese makes it out alive.

The quicklime was, of course, Olintecke’s idea- and now, with the core of the Portuguese army in the region gone, he sets about hunting the rest. More victories follow, and numerous smaller forces begin to scatter. Tlacotzin isn’t idle either- while the bulk of the army are with Olintecke, he summons a small force of mercenaries to retake control of the Portuguese contexts. Slowly, step by step, the pressure on Tenochtitlan begins to ease. By 1601, the colonial forces have given up hope of progressing their gains any further, and finally sue for peace.

The Europeans claim victory in the Third Mosquito War. The Aztec reluctantly relinquish sovereignty over Colombia, and their nation has been thoroughly battered from all sides. But despite this, Tlacotzin has gained far more than he has lost. He has retained control over the north, paid no silver for peace: and despite both their numbers and technological superiority, the Europeans could not take Mosquito from him. The Aztec star is still rising.