First Vic2 AAR here. I picked the Papal States because a) they start small with opportunity for growth and b) no one else on the front page picked them. I plan on having it be in "history book" form. I didn't want it be a pure gameplay AAR because I'm not very good and a gameplay format would probably just end up being a chronicle of my numerous errors.

My last AAR was in EU3, and there I ran into the problem of becoming bored with the game and then abandoning the AAR. I don't want to do that here, so I actually made sure I finished the game before writing this. I got a few hundred screenshots to crop though, so there'll still be some time between the updates. Plus, this allows for some ominous foreshadowing later on. Hope you enjoy it.

Since the middle ages the Pope, the head of the universal Catholic Church and Vicar of Christ, had not only enjoyed ecclesiastical primacy in the Catholic world, but also directly ruled a collection of city-states in central Italy. In the beginning it was hoped that a state ruled by the Pope would become a veritably Utopia, a heaven on earth. But though Paradise did not appear, a very curious thing did. These were the Papal States, where the temporal power of the Pope held sway. In a world of familial monarchies and republics, the Papal States were a unique entity. Absolute power were held by one man, the Pope. However, the Pope was an elected monarch. And as the Popes all took a vow of celibacy, none had legitimate children to pass their title on to. Also, since it would not do to have the head of Catholicism be seen "cracking skulls", a great deal of authority was delegated to certain Cardinals, such as the Cardinal Secretary of State. The physical dimensions of this domain had not changed greatly for centuries, until the coming of Napoleon temporarily deprived the Pope of his lands and set up a revolutionary Second Roman Republic.

Since the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna, the Papal States had been ruled by a reactionary administration known as the Ristorazionista - "the restorationists". The Ristorazionista's agenda included the full integration of the Church and the state. No one espousing support for revolutionary or liberal views on separation of the spiritual and temporal powers of the Pope could expect any advancement in even local government. North Italians from Romagna were also commonly treated as second-class citizens compared to the South Italians of Lazio, the base of support for the regime.

The French also commanded a great deal of influence in the politics of Rome. Though it had been the French Empire which presumed to remove the temporal power from the Pope those short decades ago, the new post-Napoleonic regime in France was on good terms with the Papacy.

The Ristorazionista and their leader, the Cardinal Secretary of State Luigi Lambruschini, had the complete support of Pope Gregory XVI. Pope Gregory had been elected in 1831. Strongly conservative and traditionalist, he opposed the democratic and modernizing reforms which had become popular elsewhere in Europe since the wars of the French Revolution, seeing them as a front for revolutionary forces which would destroy the almost two thousand year-old Church. He and Cardinal Lambruschini, opposed basic technological innovations such as gas lighting and railways, believing that they would promote commerce and increase the power of the bourgeoisie, leading to demands for liberal reforms which would undermine the monarchical power of the Pope over central Italy. Gregory in fact banned railways in the Papal States, calling them "ways of hell". Though later Popes would relax these prohibitions and even attempt to encourage industrialization, the Papal States would never amount to an industrial power of any degree.

The Pope's small military consisted of a few brigades of Papal Zouaves. The Zouaves were for the most part not residents of central Italy, but international Catholic volunteers. All orders were given in French and they were commanded by a Swiss Colonel until the command was offered to Ludovico Chigi. This arrangement obviously did little to endear the Papal military in the eyes of the citizens of the Papal States, and was frequently cited in republican and Italian nationalist pamphlets which occasionally circulated illegally.

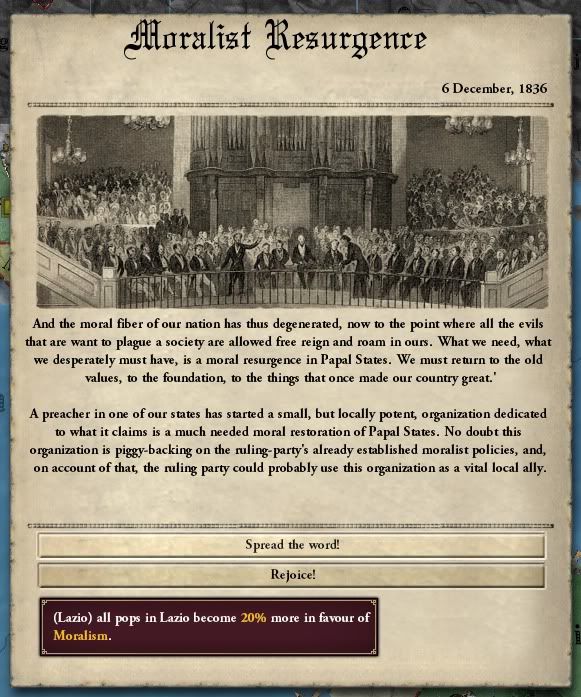

The Ristorazionista further cemented their privileged status in the eyes of Pope Gregory by successfully sparking a moralist resurgence. New religious societies were springing up left and right, it seemed. While the radical tide might have been rising in other states, in the Papal States the people cried for stability, and for things to remain as they had always been. The Revolution had brought war and misery. Who would ever want to encourage that?

These were the Papal States in 1836. Almost diametrically opposed in an ideological sense to their patron, the Orleaniste monarchy of France, the Papal regime many of the people it ruled were reactionary, moralist, and technologically backward.

Pope Gregory and Cardinal Lambruschini did not rest easy. The radical elements in Italy may have been silenced for the time being, but no one was under the illusion that they were not there. A revolution in one of the other states of Italy could lead to a crisis, even war. The Pope had seen it before. During Napoleon's day the revolutionaries had not been content to keep their disease in France, but enthusiastically sought to spread the contagion through war. The Pope began to actively court the other powers of Italy. The Grand Ducies of Modena, Tuscany, Lucca and Parma were firmly in the Austrian sphere of influence, and their Habsburg masters did not take kindly to any kind of outside interference. The two most important independent states of Italy were the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the south and the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in the north. It was the latter to which Pope Gregory focused his attention.

Carlo Alberto, King of Sardinia-Piedmont

Carlo Alberto, the King of Sardinia-Piedmont who had come to his throne around the same as Pope Gregory, was receptive to the idea of an alliance. And so in September of 1836 the King and the Pope announced their everlasting friendship and cooperation to the rest of the world. Pope Gregory could finally rest easy. His sbirri would keep order in the Papal States well enough, and if by chance revolution should overtake one of the other Italian states, he could call on Sardinia-Piedmont to aid him in restoring order.

Some Cardinals did voice displeasure at the arrangement. They were concerned the treaty was far to vague and broad. They did not trust the King. Because Carlo Alberto was not widely regarded as a peace-loving man. His arguments with the Swiss to his north had already produced deadly border skirmishes. Only two weeks before the signing of the treaty five Swiss and two Sardinian border guards had been killed. But though he undoubtedly regarded some Swiss border towns as his, and did not shy away from forceful negotiations, the Pope still approved of him. Carlo Alberto, he was convinced, was no warmonger. "I looked into his eyes and could glimpse his soul", he remarked.

It seemed that the efforts of the Ristorazionista in encouraging mistrust of North Italians and their motives had proven a bit too successful. Cardinal Lambruschini brushed aside these concerns as the ramblings of paranoiacs. "They would sacrifice the peace and stability the States of the Church," he wrote in his diary, "all on the fear the King of Sardinia-Piedmont will attempt to use the Pontifical Zouaves as a force to supplement some mad scheme of conquest."

In October the Pope issued his encyclical "In Amicos Fides", decrying the suspicion being heaped upon his new ally. It seemed like the arguments refused to end even though the treaty itself was signed and done. It took until Christmastime, but eventually things did die down. In Rome, the Pope celebrated the Christmas mass and looked forward to living out his reign in peace and stability.

In Turin, Carlo Alberto prepared for war.

My last AAR was in EU3, and there I ran into the problem of becoming bored with the game and then abandoning the AAR. I don't want to do that here, so I actually made sure I finished the game before writing this. I got a few hundred screenshots to crop though, so there'll still be some time between the updates. Plus, this allows for some ominous foreshadowing later on. Hope you enjoy it.

"Only a few prefer liberty - the majority seek nothing more than fair masters."

-Sallust, Histories

God's Empire

Chapter I: Introduction (1836)

-Sallust, Histories

God's Empire

Chapter I: Introduction (1836)

The States of the Church

Since the middle ages the Pope, the head of the universal Catholic Church and Vicar of Christ, had not only enjoyed ecclesiastical primacy in the Catholic world, but also directly ruled a collection of city-states in central Italy. In the beginning it was hoped that a state ruled by the Pope would become a veritably Utopia, a heaven on earth. But though Paradise did not appear, a very curious thing did. These were the Papal States, where the temporal power of the Pope held sway. In a world of familial monarchies and republics, the Papal States were a unique entity. Absolute power were held by one man, the Pope. However, the Pope was an elected monarch. And as the Popes all took a vow of celibacy, none had legitimate children to pass their title on to. Also, since it would not do to have the head of Catholicism be seen "cracking skulls", a great deal of authority was delegated to certain Cardinals, such as the Cardinal Secretary of State. The physical dimensions of this domain had not changed greatly for centuries, until the coming of Napoleon temporarily deprived the Pope of his lands and set up a revolutionary Second Roman Republic.

Since the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna, the Papal States had been ruled by a reactionary administration known as the Ristorazionista - "the restorationists". The Ristorazionista's agenda included the full integration of the Church and the state. No one espousing support for revolutionary or liberal views on separation of the spiritual and temporal powers of the Pope could expect any advancement in even local government. North Italians from Romagna were also commonly treated as second-class citizens compared to the South Italians of Lazio, the base of support for the regime.

The French also commanded a great deal of influence in the politics of Rome. Though it had been the French Empire which presumed to remove the temporal power from the Pope those short decades ago, the new post-Napoleonic regime in France was on good terms with the Papacy.

His Holiness Pope Gregory XVI, 1836

The Ristorazionista and their leader, the Cardinal Secretary of State Luigi Lambruschini, had the complete support of Pope Gregory XVI. Pope Gregory had been elected in 1831. Strongly conservative and traditionalist, he opposed the democratic and modernizing reforms which had become popular elsewhere in Europe since the wars of the French Revolution, seeing them as a front for revolutionary forces which would destroy the almost two thousand year-old Church. He and Cardinal Lambruschini, opposed basic technological innovations such as gas lighting and railways, believing that they would promote commerce and increase the power of the bourgeoisie, leading to demands for liberal reforms which would undermine the monarchical power of the Pope over central Italy. Gregory in fact banned railways in the Papal States, calling them "ways of hell". Though later Popes would relax these prohibitions and even attempt to encourage industrialization, the Papal States would never amount to an industrial power of any degree.

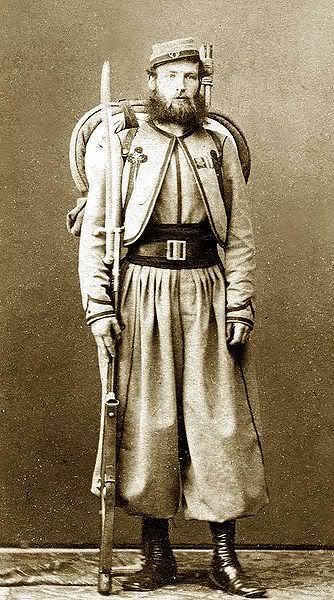

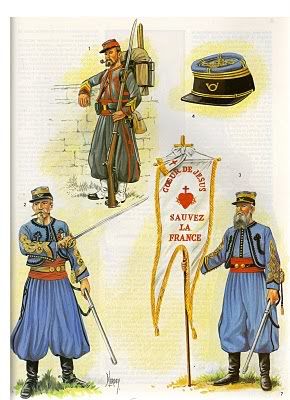

A Papal Zouave, circa 1836

The Pope's small military consisted of a few brigades of Papal Zouaves. The Zouaves were for the most part not residents of central Italy, but international Catholic volunteers. All orders were given in French and they were commanded by a Swiss Colonel until the command was offered to Ludovico Chigi. This arrangement obviously did little to endear the Papal military in the eyes of the citizens of the Papal States, and was frequently cited in republican and Italian nationalist pamphlets which occasionally circulated illegally.

The Ristorazionista further cemented their privileged status in the eyes of Pope Gregory by successfully sparking a moralist resurgence. New religious societies were springing up left and right, it seemed. While the radical tide might have been rising in other states, in the Papal States the people cried for stability, and for things to remain as they had always been. The Revolution had brought war and misery. Who would ever want to encourage that?

These were the Papal States in 1836. Almost diametrically opposed in an ideological sense to their patron, the Orleaniste monarchy of France, the Papal regime many of the people it ruled were reactionary, moralist, and technologically backward.

Pope Gregory and Cardinal Lambruschini did not rest easy. The radical elements in Italy may have been silenced for the time being, but no one was under the illusion that they were not there. A revolution in one of the other states of Italy could lead to a crisis, even war. The Pope had seen it before. During Napoleon's day the revolutionaries had not been content to keep their disease in France, but enthusiastically sought to spread the contagion through war. The Pope began to actively court the other powers of Italy. The Grand Ducies of Modena, Tuscany, Lucca and Parma were firmly in the Austrian sphere of influence, and their Habsburg masters did not take kindly to any kind of outside interference. The two most important independent states of Italy were the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the south and the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in the north. It was the latter to which Pope Gregory focused his attention.

Carlo Alberto, King of Sardinia-Piedmont

Carlo Alberto, the King of Sardinia-Piedmont who had come to his throne around the same as Pope Gregory, was receptive to the idea of an alliance. And so in September of 1836 the King and the Pope announced their everlasting friendship and cooperation to the rest of the world. Pope Gregory could finally rest easy. His sbirri would keep order in the Papal States well enough, and if by chance revolution should overtake one of the other Italian states, he could call on Sardinia-Piedmont to aid him in restoring order.

Some Cardinals did voice displeasure at the arrangement. They were concerned the treaty was far to vague and broad. They did not trust the King. Because Carlo Alberto was not widely regarded as a peace-loving man. His arguments with the Swiss to his north had already produced deadly border skirmishes. Only two weeks before the signing of the treaty five Swiss and two Sardinian border guards had been killed. But though he undoubtedly regarded some Swiss border towns as his, and did not shy away from forceful negotiations, the Pope still approved of him. Carlo Alberto, he was convinced, was no warmonger. "I looked into his eyes and could glimpse his soul", he remarked.

It seemed that the efforts of the Ristorazionista in encouraging mistrust of North Italians and their motives had proven a bit too successful. Cardinal Lambruschini brushed aside these concerns as the ramblings of paranoiacs. "They would sacrifice the peace and stability the States of the Church," he wrote in his diary, "all on the fear the King of Sardinia-Piedmont will attempt to use the Pontifical Zouaves as a force to supplement some mad scheme of conquest."

In October the Pope issued his encyclical "In Amicos Fides", decrying the suspicion being heaped upon his new ally. It seemed like the arguments refused to end even though the treaty itself was signed and done. It took until Christmastime, but eventually things did die down. In Rome, the Pope celebrated the Christmas mass and looked forward to living out his reign in peace and stability.

In Turin, Carlo Alberto prepared for war.