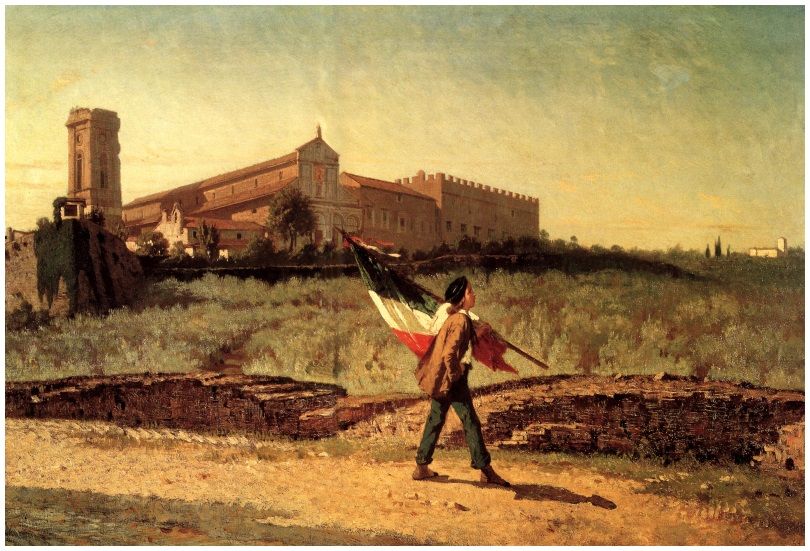

Forza Italia!

"You may have the Universe, give me only Italy."

- Giuseppe Verdi

Risorgimento

I. New Beginnings

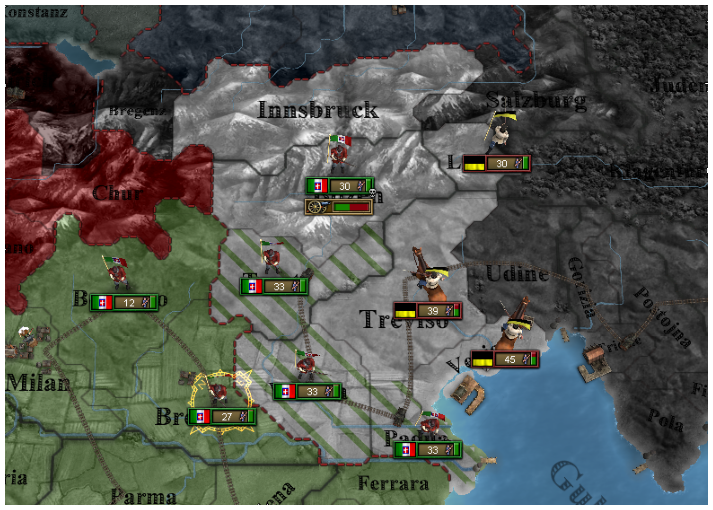

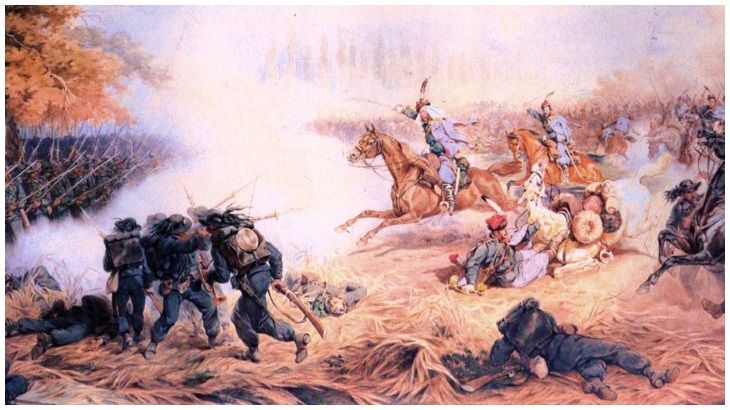

II. Venetian War (1861-1862)

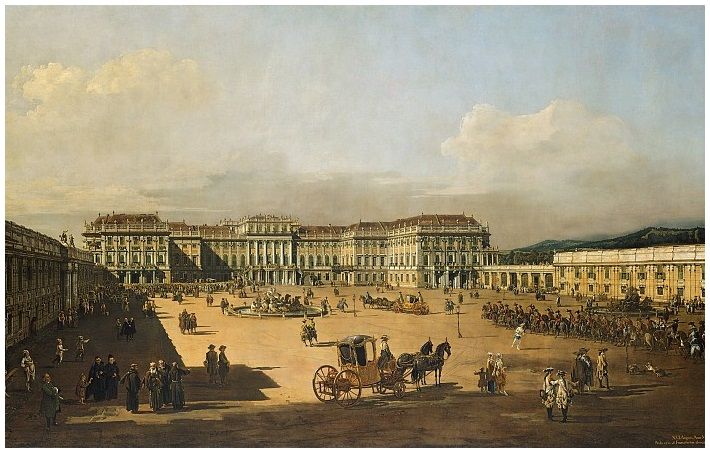

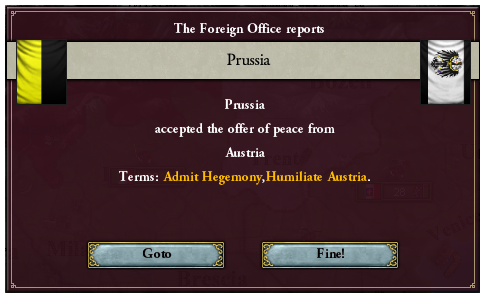

III: Treaty of Schönbrunn

IV: Election of 1863

V: The Ricasoli Ministry

VI: Hungary and Rome

VII: The Triple Alliance

VIII: War of 1872

IX: Taranto

X: Treaty of London

Imperialismo

XI: Boxer Rebellion

XII: Year of the Three Kings

XIII: Tunisian War

XIV: Club Africano

Appendix 1: Italy in 1880

I. New Beginnings

II. Venetian War (1861-1862)

III: Treaty of Schönbrunn

IV: Election of 1863

V: The Ricasoli Ministry

VI: Hungary and Rome

VII: The Triple Alliance

VIII: War of 1872

IX: Taranto

X: Treaty of London

Imperialismo

XI: Boxer Rebellion

XII: Year of the Three Kings

XIII: Tunisian War

XIV: Club Africano

Appendix 1: Italy in 1880

Last edited: