Falls The Shadow: A German AAR

- Thread starter Pelican Sam

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

| Author's Note: After a hiatus I've returned to the project. I tried to intall Black ICE and it corrupted my game folder, or in some other way made the game fail to load. I had hoped to fix it without having to redownload the game on Steam, but alas, it was not meant to be. Though I still can't get Black ICE to run properly, the saved game seems to be fine so I figured I'd might as well continue with this. | |

Last edited:

|

| Author’s Note: I either lost all of my data for what happened during this phase of the conflict, or never bothered to keep track of anything, so I’ve had to wing it as best as I can using my faulty memory and final troop positions to fill in the gaps. I apologize for any confusion or inconsistencies between this installment and previous ones. Oberleutnant zur See Wolfhart Vogt dropped waist-deep into Danzig Bay at 0642 hours on September 10. The 24-year-old waded to shore and quickly made his way across the gravelly beach, towards the cover of a low concrete seawall, stumbling as he ran. In front of him he could see plumes of black smoke rising from within the city towards the overcast sky where the nine 28cm guns of the battlecruiser Sharnhorst had bombarded the city’s coastal defences, and where for days the Luftwaffe had bombed the city from on high. By the time Vogt and No. 3 platoon had landed in the city of Danzig the garrison responsible for defending his section of beach had mostly abandoned their positions. All that remained were a handful of troops, no more than a platoon in size, facing down a company of German marines. “When I looked back after making it to the wall I saw that not one of my men had fallen,” Vogt would later recount. “One by one they all slammed into the wall around me, taking cover from the bursts of machine gun fire that kicked up stones around us. None of us could believe our good fortunes. Not a single one of us had been so much as wounded—to say nothing of dying! What happened on that beach was a miracle.” 1. Company would later learn from its prisoners that the reason for such a lackluster defence had been the shelling. Terrified, the majority of the Polish garrison had fled back into the city abandoning their relatively exposed positions on the beach. Those who remained were mostly conscripts who had become separated from their parent units in the shelling and didn’t know what to do. Although they offered sporadic machine gun fire from what few support guns they still had, by the time the first German Marines had made it to the cover of the low seawall, the Polish conscripts still guarding the beach had already begun throwing down their arms in surrender. Without any leadership to guide the Polish troops, the battle for control of the Marine-Sturm-Regiment’s landing site was over within twenty minutes. Vogt’s company had secured its primary objectives largely without firing a shot. “To achieve flawless victory there is no substitute to hard work and training,” Vogt wrote of his company’s victory that day. “But fighting the Polish army comes close [as a substitute].” Though the victory had come easily for the German marines, it did not come freely for the Regiment. Four marines were killed in the landing, and another 17 wounded. But this number was still much lower than military planners had expected. Facing a proper Polish defence, estimates for initial casualties had been as high as 200 dead before the German marines had even been able to make their way off the beaches; that only four had died and under 20 had been wounded gave a great sense of pride to the regiment’s commander, Oberst Eckart Kolb, who was keeping a close eye on the regiment’s first foray into combat. |

German soldiers moving through Danzig. |

| Keeping close tabs on the operation as well was Chief of the Kriegsmarine, Großadmiral Erich Raeder. Marine-Sturm-Regiment 172 was an experimental regiment that had been commissioned and trained under Raeder’s directive, and its success or failure at Danzig would determine as much the fate of the battle as that of his career in politics. If the regiment failed it would no doubt give Göring (who had been at odds with Raeder over his appointment of Chief of the Kriegsmarine for the better part of two years) the impetus to have Reader dismissed. Alternatively, if the Marine-Sturm-Regiment proved an effective fighting force, Raeder hoped for permission to expand the force into an entire division, maybe even eventually a corps. To that end the Chief of the Kriegsmarine had insisted on very stringent guidelines for recruiting to the regiment. All volunteers, in addition to being from the Kriegsmarine branch of service, had to be vigorously fit and have advanced training in either weapons or demolitions. Even still, of the recruits who passed the initial selection process, more than 60% of its volunteers failed out during training. It was due to this high failure rate that the regiment was formed as a regiment and not a division as was originally planned. In Reader’s mind, it was better to have the cream of the crop prove the worth of the idea, than to push for a whole division of less capable men. With such rigid guidelines for recruitment and the most strenuous training the Kriegsmarine had to offer, Großadmiral Reader had no doubt that his regiment would be able to secure the beaches and get the job done. Göring, however, was not so confident. With the ear of the Fuhrer, Göring was able to convince Hitler that Raeder’s experiment had been a failure and that the marines would fail to gain a foothold on the beach. Göring instead suggested that a regiment of Fallschirmjäger be attached to a second infantry division that would assist the marines in gaining a foothold. Trusting his close personal friend over concerns raised from the Chief of Staff Ludwig Beck, Hitler ordered a second infantry division—with Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6 in the lead—to also attack by sea alongside 59. Infanterie-Division. Göring hoped that competing directly with the Marine-Sturm-Regiment would highlight the successes of the Fallschirmjäger and display the failures of the Marine-Sturm. When all was finally said and the political maneuvering done, the invasion plan for Danzig called for two divisions of infantry to attack the city by sea, while the four infantry divisions that had surrounded the city would also join in the attack. The two divisions landing by sea would be comprised of six infantry regiments (Infanterie-Regiments 167, 178, and 185 attached to 59. Infanterie-Division, and Infanterie-Regiments 179, 195 and 196 attached to 63. Infanterie-Division) and Marine-Sturm-Regiment 172 and Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6. Marine-Sturm-Regiment 172 would land on the left flank of the city’s ports, securing a landing zone while Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6 would simultaneously land to the right of the ports, securing a landing zone there as well. Both would clear landing sites for the remainder of 59. Infanterie-Division and 63. Infanterie-Division, respectively. Once landing sites had been secured Marine-Sturm-Regiment 172 and Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6 would link up in the port district, cutting off the ports from the rest of the city and linking the landing zones. The six other regiments of infantry, meanwhile, would push into the city and link up with the 8. SS Kavallerie-Division and 1. Infanterie-Division on the north and south flanks, respectively. It was expected that the battered Polish forces in Danzig, already having fought several bloodied conflicts in the war, would surrender quickly once the German troops began squeezing them farther and farther into the city. By 0730 the plan was already going better than expected. The second wave of reinforcements, 5. Company, had assembled on the beach and were on their way to secure the port, a full five hours ahead of schedule. But the good fortunes of the invasion force were exhausted quickly as the Marine-Sturm’s 5. Company became bogged down in a bitter street fight with elements of 22nd Polish Division. By 0900 hours Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6 had also been stalled in its advance towards its objective. The Polish forces had seemingly anticipated the intentions of the Germans and had moved a battalion’s worth of men to defend the port. As more reinforcements flowed onto the beach from the transports in Danzig Bay, 1. Company was released from guarding the beach and ordered south to assist 5. Company in ousting the Polish defenders. 1. Company, however, had little more success against the Polish defenders than 5. Company had. Using the bombed out ruins of warehouses and the rubble that had cut off roads around the ports, the Polish infantry had stalled the attack and made it virtually impossible for 1. Company to link up with Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6. After their initial successes on the beach, Vogt realized many of his men had quickly gained a false sense of superiority in regards to the Polish army. “We thought we were unstoppable. We thought the Polish army was only made up of those types of men who had surrendered on the beach—just boys, really—who would give up as soon as we started shooting back. But they weren’t. The Poles were tough.” |

Dornier Do-17 in action above Poland |

| While a bitter street fight raged on in the city, in the skies above Danzig there was no fight to be found. The Polish air force had yet to venture into the sky since their one-sided defeat on the campaign’s first day. The Polish air force had elected to stay afield of any real danger by basing themselves in the Jaworow province far east of where the Luftwaffe was operating. Though this conserved the Polish air force from further losses, it was disastrous for Polish troops on the ground. The Luftwaffe ruthlessly punished any movement of troops or supplies made by the Polish forces on a tactical or strategic level in western Poland, and in Danzig specifically. Day and night, tactical and dive bomber groups flew sorties over the city, repeatedly hitting known and suspected targets from September 3 onward. It is estimated that more than 300 tonnes of explosives were dropped on Danzig on September 10 alone as a part of the operations to take the city. So destructive were the Luftwaffe’s bombing sorties that, of the nearly 6,500 estimated casualties caused by the Luftwaffe during the invasion of Poland, nearly 2,000 casualties occurred in Danzig. As the morning came on September 11 Marine-Sturm-Regiment 172 and Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6 had yet to link up, though elements of 59. Infanterie-Division and 63. Infanterie-Division had been able to link up with the 8. SS Kavallerie-Division and 1. Infanterie-Division before dawn. A few short hours after the divisions were able to link up, 1. Company finally managed to break through the defensive line that the Polish army had set-up and linked up with Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6. |

59. Infanterie-DIviion and 1. Infanterie-Division linking up on the outskirts of Danzig. |

| Großadmiral Raeder was still onboard the Scharnhorst on September 11. He had barely slept the night before, catching only a few winks in the ship’s bridge when he had closed his eyes for too long. Throughout the night had sat, watching the flickering lights across the bay as mortars and artillery splashed down around the port, illuminating the night. He had listened intently from the bay to the distant echoes of machine gun fire that sputtered out across the water. Exhausted after his long night of waiting for any news of a breakthrough, he was elated to hear, just after dawn, that the Marine-Sturm-Regiment had broken through the stalemate and linked up with Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6. Raeder took a deep sigh and then laughed to himself. “Give them all a medal,” he’d said wearily to his aide and then retired from the command bridge to sleep for a few hours. Oberleutnant zur See Wolfhart Vogt and his No. 3 platoon had also spent the night with little to no sleep, but unlike the Großadmiral they did not have the luxury of sleeping now. Though they had secured a link with the other beach, the battalion of Polish defenders had not stopped resisting as they had been expected to. Stubbornly the Polish army held on to every city block as Vogt and the rest of Marine-Sturm-Regiment 172 began moving deeper into the city. Across the rest of Poland the fighting had died down. Though the Polish army still had its troops in the east, they had remained stationary, unwilling to move against Germany lest the Soviet Union should take advantage of their situation and join the attack. All across western Poland, however, the Polish army had been all but vanquished. The only forces that remained were trapped at Chrzanow, Poznan and Danzig. The government had fled east before the fall of Warszawa and General Syzlling, now-commander of the western Polish forces, had slipped out of Warszawa on the 9th. Under the cover of darkness he had fled eastward to regroup with those Polish forces based along the Soviet-Polish border. By 1400 hours, the Polish troops at Poznan finally surrendered. As another 25,500 Polish soldiers laid down their arms and marched into captivity the Polish government made a radio broadcast urging each soldier “not to lay down your arms, but to fight. Fight to the bitter end, to the very last man”. Though the words might have sounded poetic when first thought up by the government, they came out flat and hollow to most of the Polish troops who knew already that the war was lost. For those soldiers still trapped at Chrzanow or Danzig, they were already waiting for the release of surrender, or death. Despite the attempts of the Polish government to inspire its soldiers continue the war, on September 12 at 1000 hours Lt. General Przedrzyminski-Krukowicz, commander of the Polish garrison of Danzig, sent out a white flag and by 1200 hours had formally surrendered to Generalmajor Bergmann, commander of 8. SS Kavallerie-Division. As the last true bastion of Polish resistance collapsed and the last western Polish city fell to German occupation, the Polish government at last agreed to the unconditional surrender of its forces. Almost exactly one day after its broadcast on the 11th, just after 1400 hours, the Polish government broadcasted a statement of surrender calling for all Polish troops to lay down their arms and surrender to the German army. Just before midnight the last of the Polish troops in Danzig and the Chrzanow pocket surrendered to the German army. After ten days of fighting, the war in Poland was officially over. |

Last edited:

Haha! It lives!!

Long breaks without forewarning from the author is usually a sign of AAR death!

Long breaks without forewarning from the author is usually a sign of AAR death!

haha, thanks guys! I thought I'd lost the game for sure when my game started crashing at start-up, so I didn't see a point in finishing off what I had ready to write. But it seems as though whatever problem I caused by trying to install the mod fixed itself after the game was re-downloaded.

haha, thanks guys! I thought I'd lost the game for sure when my game started crashing at start-up, so I didn't see a point in finishing off what I had ready to write. But it seems as though whatever problem I caused by trying to install the mod fixed itself after the game was re-downloaded.

So many people talk about save corruptions, in all my years of playing Paradox games (going on 9 years now, I've only experienced one "corrupted" save in an old HoI2 Netherlands game of mine).

Well, glad to see everything is fine Sam!

|

| At 0200 hours on October 1, two submarines left their port of harbour at Kiel as a part of Unternehmen Unbekannte Größe (Operation Dark Horse). Quietly they glided towards the shores of Lolland, the nearest island of the Danish chain. At 0225 hours they stopped at a pre-arranged location in neutral water and surfaced. In a flurry of communications to their base at Kiel the two submarines of 1. Unterseebootsflottille relayed that their companion sub, U-192, had been sunk without provocation by a Danish cruiser in neutral waters. Almost immediately the information was relayed to German propagandists. Messages were recorded for radio broadcast condemning the Danish act of war, urging the people and the government to avenge the 12 sailors who had been killed. By midday propaganda films had even been spliced together showing sailors being rescued from the water. |

An image distributed by the Kriegsmarine, showing a U-192 sailor being pulled from the water after the sinking of U-192. |

| In actuality, there had been no attack by Danish cruisers against the 1. Unterseebootsflottille detachment of submarines. In fact, there was not even a U-192 in the German Kriegsmarine at the time. ‘The Guldborgssund Incident’, as it wöould later become known, had been a carefully planned misinformation operation conducted by the German Kriegsmarine that intended to give cause for Germany to invade Denmark. By 1600 hours, in a secret parliamentary meeting, Hitler had signed Directive 99 ordering the German military to begin the invasion of Denmark no later than October 3. Even before the day had ended on October 1, German soldiers were already aboard troop transports at Stettin, steaming towards Danish shores. For Germany, Denmark was a vital objective for several reasons. Firstly, it was the gateway to the Baltic Sea, through which all vessels had to pass. German naval supremacy in the Baltic was entirely determinant upon the numerically superior French and British fleets being denied access to it. If French or British forces were allowed to pass through Denmark to the Baltic, then all German supremacy there would evaporate. The Baltic Sea of course protected northern Germany from being invaded, but also protected the vital German convoy routes with Sweden that supplied Swedish metal to German factories. If Denmark allowed passage to French or British fleets, German convoys in the Baltic would come under threat from marauders, and Germany’s only ports would become blockaded. As a nation that was highly reliant upon imports of metals and rare materials, such a blockade would be crippling to Germany’s ability to fight an offensive war. Secondly, an invasion of Denmark offered a base of operations from which an attack could be launched on Norway, which was considered a prize by the German Kriegsmarine for its ports in the North Sea. Ports which could be used to house U-boat flotillas that would then be able to interdict supplies travelling through the Atlantic from North America to the United Kingdom. Thirdly, the failure to invade Denmark early could potentially cause Denmark to ally itself with the allied western nations of Britain and France, and allow those nations to land troops voluntarily on its shores. In such an instance, German troops from other fronts would need to reinforce the northern border. “And if the last war had been any indication of the coming conflict,”—acknowledged some military planners—“Germany would need every last available man to mount a successful offensive in the west.” And so, before the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia had even been ceded to Germany, Fall Blau (Case Blue), had been proposed at a military conference in Berlin, and unanimously accepted by Hitler and the general staff of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht. Immediately after Germany’s victory over Poland preparations began for Fall Blau. Within hours of the Polish capitulation, troops and supplies began diverting towards the Jutland peninsula and the German port of Stettin, with orders for all troops there to “begin preparing for invasion”. In charge of the invasion would be Werner von Fritsch, of the newly created 11. Armee based in Kiel. For the invasion 11. Armee was to have four corps at its disposal: two panzer corps and two infantry corps, to be transferred from the now defunct Polish theater. The plan called for III. Panzerkorps and IV. Armeekorps to advance from the northern German border and take the Jutland peninsula, while XXIII. Armeekorps and XXII. Panzerkorps would land by air and sea on the Danish islands of Funen and Zealand, taking the city of Odense and the capital of Copenhagen. It was expected that Denmark would fall in under a day, with the Danish forces quickly capitulating to the superior German army. |

The invasion plan for Fall Blau. |

| Early in the morning on October 2, 1939, as his transport steamed towards the Oresund under the cover of a dark moonless night, Schütze Hermann Rantzau knew very little as to why Denmark was being invaded. “We knew the islands were important—why else would they be sending us?—but we knew very little of why they were so important at that moment.” Details that trickled down to the enlisted men were mostly spotty rumours. Some men said that the British had landed in Denmark, and Germany had to save its small neighbour; other men said Denmark had declared war on Germany; and others still said that Denmark had requested German intervention for fear of being invaded by the United Kingdom. At the higher echelons of command each commander had a general idea of what the invasion entailed and why the invasion had to be undertaken, but in the mad dash to relay troops to their starting lines commanders at the divisional level and lower had been given only basic details of the invasion itself. From there, some more imaginative officers had embellished small details as to why Germany was going to war with Denmark. By the time the information made its way down the grapevine to men like Rantzau it was a jumbled mess of contradictions. “All I knew for sure was: Denmark. I didn’t know if they’d be shooting at us, or waving flags at us when we got there, all I knew was ‘Denmark’.” As the transport fleet of 1./I. Truppentransporteflotte glided across the calm waters of the Baltic Sea near the Pomeranian Coast towards Denmark, Schütze Rantzau made the best of his trip lying in his bunk, wishing for sleep that would not come. The other men of 59. Infanterie-Division onboard the Freiheit busied themselves also with sleep, or else each also enjoyed a quiet game of cards or dice in the lower hold of the ship. “I felt very little apprehension. I was at peace in my bunk. I can’t describe the feeling I had then, but it was as though everything was to work out for me. I wasn’t going to be killed. I was going to come through it unharmed. This I knew, but still it was impossible for me to sleep,” Rantzau recalled. The rest of the men, he remembered of the time he was awake, also seemed to be at peace. “We thought ourselves the best soldiers in the world. We had smashed through Poland in a week and change. Whomever we were going to fight in Denmark, be it the Danes or the English, we would win.” One hundred kilometers north of the transport ship Freiheit, on board the German battleship Bismarck, a very similar sense of inevitable success could be found in its crew as they entered the Kattegat channel early on October 2. Launched June 14, 1938 the Bismarck had served for a year and a half as the pride of the German fleet, but had yet to see combat. Despite its untested nature, the crew had the utmost faith in her, and her captain, Kapitän zur See Jan Mohr. Mohr had served with distinction for the better part of thirty years in the German navy. In the interim years between wars he had had the pleasure and privilege of crewing the Deutschland heavy cruiser and commanding the battlecruiser Schleswig-Holstein, before being given command of the battleship Bismarck. Despite his years naval service, Jan Mohr was something of an idle commander, often delegating most, if not all of his tasks, to his subordinates. Though this had raised concerns among some of the more senior commanders at first, the Kapitän zur See’s overwhelming charisma provided enough reassurance to restore the faith of the senior command staff early on in his tenure. As the Bismarck floated through the Kattegat at approximately 0200h on October 2, the radio suddenly sparked to life, confirming the presence of a French fleet approaching the Schlachtflotte Nordsee. For the Schlachtflotte Nordsee this news was unexpected. The naval intelligence service of the Kriegsmarine had been adamant in its assertion that a French and British fleet would be too busy hunting German subs in the North Sea to make a move against the Kriegsmarine. The only expected threat against German landing operations in the Danish channels was to be the Danish fleet, who, it was agreed by the German High Command, were less than capable of repelling a fully supported German landing. |

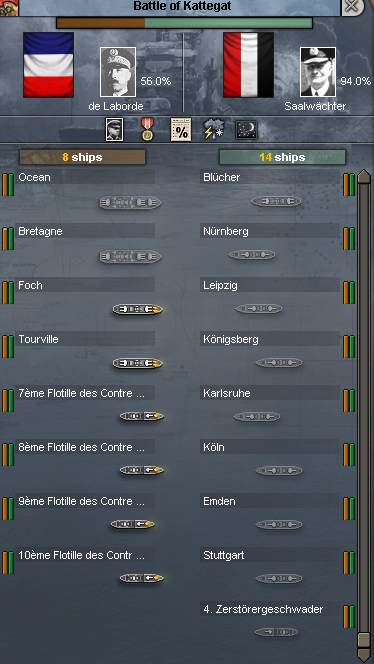

The First Battle of the Kattegat, between the 3rd French Fleet and Schlachtflotte Nordsee. Not seen: KMS Bismarck, Deutschland, Graf Spee. |

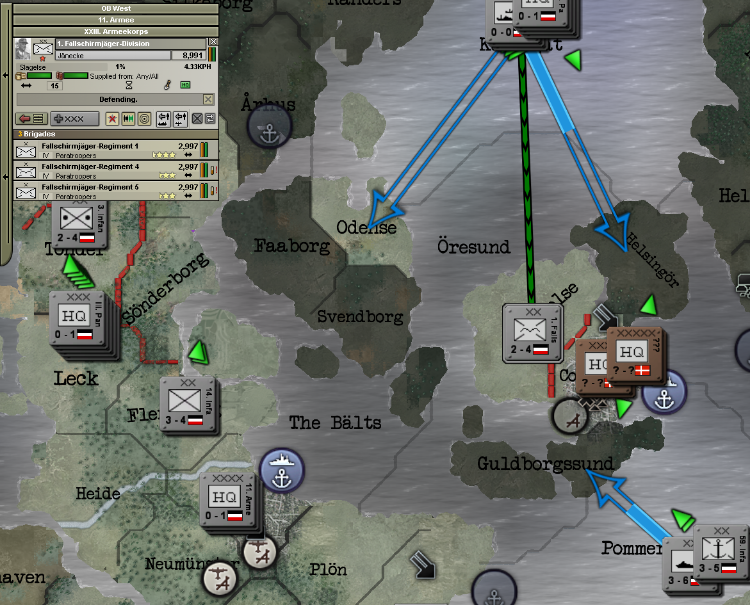

| For the crew of the Bismarck news of a likely battle was met with fervor. Cheers and hollering rang up from below the decks as the Bismarck positioned itself into formation alongside the rest of Schlachtflotte Nordsee. Meeting the German battle fleet was the 3rd French Fleet under Rear Admiral de Laborde, consisting of the Bretagne-class battleship Bretagne, the Courbet-class battleship Ocean, the Duquesne-class heavy cruisers Foch and Tourville, and four Guépard-class destroyer flotillas. The German battle fleet meanwhile was composed of the Bismarck-class battleship Bismarck; the Hipper-class heavy cruisers Deutschland, Graf Spee, and Blücher; the Nürnberg-class light cruisers Nürnberg and Stuttgart; the K-class light cruisers Leipzig, Königsberg, Karlsruhe, and Köln; the Emden-class light cruiser Emden; and one flotilla of Z1-class destroyers. Outnumbering the French fleet, the battle lasted for little more than three hours as both sides fired shells at one another from a great distance. Neither fleet seemed willing to close on the other, with both suspecting the other of having reinforcements nearby. At 0500 hours the French fleet withdrew to the north to Skagerrack, with neither side having landed a single blow on the other. For those onboard the Bismarck the whole endeavour seemed an anti-climactic way to start the war. South of Schlachtflotte Nordsee, near the Pomeranian Coast, the KMS Freiheit transport ship was steaming towards the shores of Zealand. As the Schlachtflotte Ostsee neared its embarkation point to make its landing at Copenhagen, the Danish fleet’s two heavy cruisers, the Niels Iuet-class HDMS Niels Juel and HDMS Peder Skram appeared suddenly on the horizon. Without warning they fired upon the German armada that was heading for them. In a heroic action the two vessels held their position for four hours, firing salvo after salvo at the German armada of three battlecruisers and seven destroyer flotillas. However by noon the Peder Skram and Niels Juel had both been disabled and were slowly sinking into the Baltic sea. Though the action had done little to stop, or even slow the German navy from its landing, it had achieved one remarkable outcome: the battle had forced the transports off course from Copenhagen towards the Guldborgssund instead. Though the landings at Odense, Helsingör, and Guldborgssund all began at precisely 1200 hours on October 2, as they had been planned, the presence of troops landing in Guldborgssund instead of at the harbours of Copenhagen proved a major strategic setback. Copenhagen had been an objective that the German army had wanted to quickly capture with a three-pronged attack from the sea and from land, driving the Danish defenders into the Guldborgssund where they could be isolated and effectively destroyed. However by landing at Guldborgssund, the German army had now surrounded the Danish capital and given the defenders nowhere to run. 11. Armee commander von Fritsch was furious when he received word of the mistake that had been made. At first he considered ordering the troops back into their transports and to reroute to Copenhagen, but given that several battalions had already put their forward troops on the ground in Guldborgssund he decided the action of embarking troops to reposition for an attack on Copenhagen would only waste more time. As his aides offered a situation report from the data they had collected throughout the day, von Fritsch knew that he would not have the quick victory he had hoped to achieve. Not only had the 59. Infanterie-Division and 8. SS Panzer-Division been delayed in capturing Copenhagen, but 1. Fallschirmjäger-Division had also been delayed in its airborne operations due to poor visibility conditions in Slagelse on October 2. “My plan is ruined, and I along with it,” wrote a melodramatic von Fritsch in his diary for October 2. |

The landings as of October 3, 0300 hours; In the south, the diverted landing at Guldborgssund; in the north the landings at Odense and Helsingor. Note also that 3. Inf.-Div. (mot) has made the first German gains into the Jutland peninsula in the west. |

| On October 3, at 0300 hours some good news came for the Germans as Generalmajor Jänecke and 1. Fallschirmjäger-Division landed in Slagelse, capturing their initial objectives without opposition. As October 3 went on, KMS Bismarck and the rest of the Schlachtflotte Nordsee once more found themselves in combat, this time with the British 42nd Fleet. Sailing from Dover, the fleet had arrived too late to engage the German fleet alongside the French a day earlier, but was now content to rush headlong into an engagement with the German Schlachtflotte Nordsee, despite being outnumbered. Commander Thomson, the British Commander in command of the 42nd Fleet, had the HMS Revenge and HMS Warspite under his command, two pre-Great War battleships, a light cruiser (Caledon-class HMS Despatch), and two flotillas of Battle-class destroyers. Just after 1300 hours the two British battlecruisers opened fire on elements of 5. and 7. Truppentransporterflottille, sinking a single transport of 7. Truppentransporterflottille. Moving into range was the Schlachtflotte Nordsee, which was able to quickly close with the British battleships and their screens. The HMS Despatch took a direct hit from the heavy guns of the Bismarck, disabling the engines on the Despatch and causing it to take on water. The British 49th Flotilla also took heavy fire from the Bismarck and the other heavy cruisers accompanying her. After three hours of tight maneuvering the British ships gave up their attack and retreated back towards the Skagerrack channel, leaving behind the still sinking HMS Despatch and the wreckage of the destroyed 49th Flotilla. The Schlachtflotte Nordsee had gone through the battle without taking damage; however the transports it had been screening had not been so lucky. By the end of the engagement, two ships of 7. Truppentransporterflottille had been destroyed and most of the hands onboard lost. For Jan Mohr, commander of the Bismarck, he counted himself victorious at both the strategic and tactical levels. Though the Schlachtflotte had failed to fully protect its complement of transports, it had repelled two attacks from both British and French navies and taken no damage to its own complement, as well as only minimal losses from those transport ships attached to it. |

Part 6 >> |

ahahahaha.

Taken Copenhagen quickly.

ahahahahahahahahahahaha.

you're funny.

I had a whole chapter in my AAR where I couldn't dislodge a single division from that city, even with ships firing and a good deal of bombers

Taken Copenhagen quickly.

ahahahahahahahahahahaha.

you're funny.

I had a whole chapter in my AAR where I couldn't dislodge a single division from that city, even with ships firing and a good deal of bombers

ahahahaha.

Taken Copenhagen quickly.

ahahahahahahahahahahaha.

you're funny.

I had a whole chapter in my AAR where I couldn't dislodge a single division from that city, even with ships firing and a good deal of bombers

Attacking from all 3 directions should give a large bonus to the attack.

I remember reading your AAR and being surprised at how closely our invasions of Denmark played out on land.ahahahaha.

Taken Copenhagen quickly.

ahahahahahahahahahahaha.

you're funny.

I had a whole chapter in my AAR where I couldn't dislodge a single division from that city, even with ships firing and a good deal of bombers

I've never ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, in 1500 hours of playing, seen Denmark go down in under a week. I'm sure it's possible to take them out more quickly than I do (I'm not a stellar player after all) but it's one of those weird Hearts of Iron 3 things that have never made sense to me. It usually takes me about as long to conquer Denmark as it does to conquer Poland. I think Denmark, with two divisions and two or three VPs, should last about as many days as it has divisions, but that tenacious little northern country refuses to go down.

But 11. Armee doesn't have the same hindsight I do going into this great northern debocle.

I make exceptions for no man!Poor Guderian being used as an infantry division commander

It's true though, my command structure is in shambles. I debated with myself about whether or not to min/max it at the start of the game and decided against it. I've instituted a self-imposed policy of only promoting based on merit, favouritism, and nepotism. I don't know how if it will make the game too much harder for me, but I believe it will add a little flavour to the AAR when generals are being promoted/demoted for previous actions in the field, or for their current relationship to the Fuhrer.

nice update!, but, 4 corps to conquer Denmark? just send 3 divisions and they'll surrender

I like that ideaIt's true though, my command structure is in shambles. I debated with myself about whether or not to min/max it at the start of the game and decided against it. I've instituted a self-imposed policy of only promoting based on merit, favouritism, and nepotism. I don't know how if it will make the game too much harder for me, but I believe it will add a little flavour to the AAR when generals are being promoted/demoted for previous actions in the field, or for their current relationship to the Fuhrer.

And Denmark is so powerful for their size, yeah. IIRC, they didn't really even put up much of a fight.

I make exceptions for no man!

It's true though, my command structure is in shambles. I debated with myself about whether or not to min/max it at the start of the game and decided against it. I've instituted a self-imposed policy of only promoting based on merit, favouritism, and nepotism. I don't know how if it will make the game too much harder for me, but I believe it will add a little flavour to the AAR when generals are being promoted/demoted for previous actions in the field, or for their current relationship to the Fuhrer.

I play a lot like that, I would just remark that both Guderian and Manstein were Lt. Generals at the outbreak of war.

haha, no kidding, eh? I'll have to try three divisions sometime and see how long it takes. Usually I send about six divisions (two corps or so).nice update!, but, 4 corps to conquer Denmark? just send 3 divisions and they'll surrender

Oh, I didn't realize that! I'll definitely get them promoted then as soon as possible, because you're completely right, they shouldn't be commanding just a division (which I believe both of them still are).I play a lot like that, I would just remark that both Guderian and Manstein were Lt. Generals at the outbreak of war.

Recently I've been trying to get back into the swing of writing this AAR, but I just don't have the motivation for it. I believe I shot myself in the foot early by making the updates so long. Furthermore the flow of events is something that doesn't seem to gel well with the community. There are some AARs who have done this type of presentation very well, but I think this AAR isn't one of them. It's too detail-heavy and lacks enough gameplay per chapter to make it readable. Having gone back and tried to read a few of my updates to see what I'd done in past chapters, I couldn't even get through them they were so boring to me. I'm going to regroup and try to come at this AAR-writing thing from another angle and try it again in the future, but for now this has to stop. For everyone who has followed this, I thank you, and apologize for having wasted your time. |

Too bad I loved the style, but i can see where all the extra graphics would be a huge time drain and understand. Look forward to you next attempt.