Exile in the East

- Thread starter Alfredian

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

re: Byzantium, I've never actually seen it disappear in CK, but it can shrink to very little & some very odd people become the Emperor, so all in all your Empire is doing as expected.

No odd Emperors thus far (although plenty of useless ones). Wait for the Part 12 for Emperor oddness.

Hurrah! Edgar makes an appearance! Well done on getting a Principality for yourself. A Saxon Tsar of Bulgaria - that'd be quite something to behold...

Well, I couldn't just let Edgar's line die out.

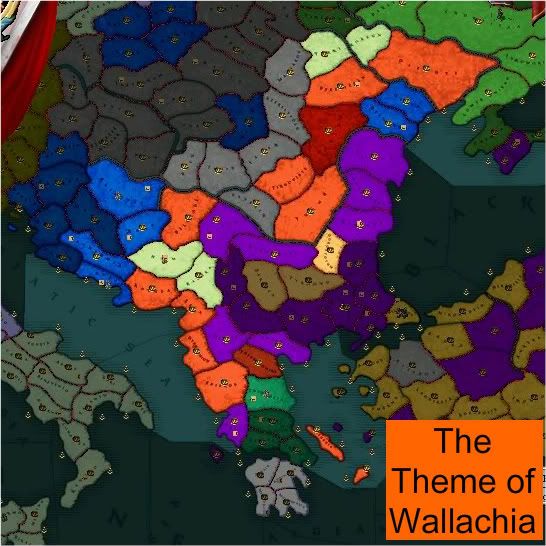

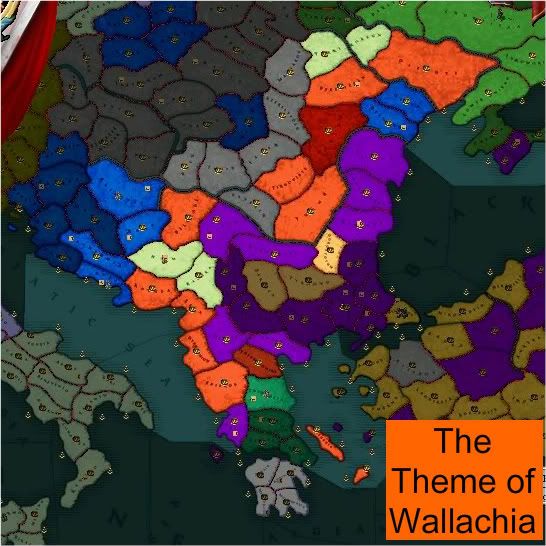

Wallachia might not be the most glamourous Princely title, but a crown (?diadem?) is a crown. Good for showing off to the neighbours (and vassalising people).

LeCare, SplendidTuesday, and mayorqw - Thank you all for reading and commenting

Just read through all of this and I really like it. I really like the love for detail mixed with an accurate description of society at the time

Saxon England and Rome/Byzantium are both areas that interest me, so it has been fun trying to mix them together.

A very interesting idea; an Saxon as a Prince of the Empire? I like it. Will be following.

Cerdic seems just barely cunning enough to thrive within the Empire; I do like his impromptu conquest of Wallachia.

I think "just barely cunning enough" is about right. He is a bit direct for Byzantine sensibilities, but then by contrast westerners often found the Greeks slippery to deal with.

Very very good so far! Awaiting for Moar updates!

February has been a very busy month and has flown by (work, my baby's christening, work, everyone catching colds from pre-school, work......). Next update coming up in a few minutes.

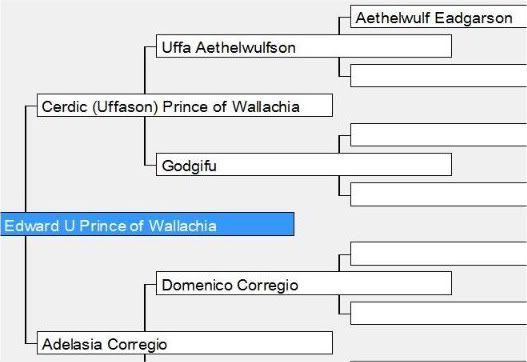

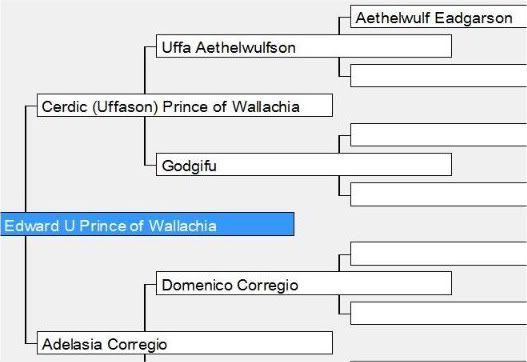

Part 11 – A favour for Domenico, a feud with Vukan (1083 to 1087)

Occasionally we are all forced to do things to please our in-laws. In most cases this involves staying in some drafty hall, nodding politely while hearing how other family members have accrued more prestige and gold than you. In Cerdic’s case it involved declaring war on the Republic of Ragusa. This small merchant republic had been increasing its share of Adriatic trade and this had not been pleasing to the merchants of Venice, including Cerdic’s father-in-law Domenico.

In 1083 Cerdic brought the men of Epirus and the new Danubian Earldoms and besieged the city by land, while Domenico’s Venetians blockaded it by sea. The siege was successful, and largely uneventful but for one incident in the last week of the siege. Cerdic had been inspecting the siegeworks and had shed his chainmail because of the heat. Possibly Cerdic strayed too near the walls, or possibly the crossbowman fired the truest shot of his life, for a bolt cut Cerdic down, severely wounding him in the shoulder. While he eventually recovered most of the use of his arm, ill health was to dog him for the rest of his days, leaving him a grimmer, harder man. The new earldom of Ragusa served as poor recompense.

While some of the life had gone out of Cerdic, everyone could see the future in the form of his eldest son Edward. Despite his English name, Edward was truly one as the new breed of Cerdic’s Varangians. He spoke Greek as his first language, yet was fluent in the languages of his parents as well (English and Italian). He also had the polished manners and education that was expected in a Greek nobleman, being literate in Greek, Latin and (at his mother’s insistence) vulgar Italian. Like many second generation immigrants he spent his time swapping between different worlds (e.g. from the Varangian drinking hall to the Greek dining room), and became adept at managing the transformation. It was because of this ability that (in 1084) Cerdic raised Edward to become Earl of the most important part of the Theme – Epirus. Edward had been born and raised there and managed to govern the locals with far less trouble that Cerdic. Edward’s Greek credentials were further strengthened when he married Aikaterina Parapondylos, daughter of the Isaakios, Prince of Crete.

In 1085 Cerdic began plotting against Emperor Constantine XI. This was potentially a very dangerous move, yet Cerdic handled it with a political deftness that enabled him to simultaneously discredit the Emperor and secede from the Empire. The nature of this secession has been fiercely debated over the years. Some say that Cerdic was fully independent, others that his domains were still part of the Empire, but withheld their taxes. The facts that we know for sure are that in 1085, Cerdic began issuing his own coinage and stopped paying tax to Constantinople, but the Empire’s law still applied in his realm (as attested by various charters issued by Cerdic during the period).

If Cerdic showed shrewdness in his handling of the secession, he showed none in his relations with his new neighbour Vukan Vojislavljevic (the Count of Zeta and vassal of the Serbian Prince of Rashka). The two of them detested each other on sight, trading insults first in person and then by letter. By the middle of 1085 the border between Cerdic’s new Earldom of Ragusa and Vukan’s County of Zeta was a wasteland, stripped bare by raid and counter-raid. Cerdic’s reaction was to escalate the conflict and formally declared war. This was to be tough and evenly matched contest between Cerdic Prince of Wallachia and the combined forces of the Prince of Rashka and Count of Zeta.

The war started badly, as the Earldom of Turnu erupted into rebellion again, delaying Cerdic’s departure with the Danubian levies. This left Earl Edward to lead the Epirot and Ragusan levies alone. These performed creditably, driving off the Count of Zeta and besieging his strongholds. To build on this success, Cerdic led the Danubian levies directly against the lands of the Prince of Rashka. It was a strange battle that saw the Count of Zeta fleeing from Earl Edward, straight into the army of Prince Cerdic. It should have been a straightforward victory, and would have been had Cerdic not insisted on trying to personally cut a path through Count Vukan’s bodyguard to take the head of his adversary. Instead, it was Cerdic who was cut down (with a blow to the thigh) and bled to death on the field even as his huscarls went berserk and slaughtered the last of the Serbs.

How would the Theme of Wallachia react to the death of the man who created it? Would the soldiers follow the 17 year old Earl Edward Uffason, or chose a more experienced man to take the princely diadem? Edward responded confidently, like a young man who had been raised to rule his peers. He already held the loyalty of the levies from Epirus and Ragusa, and called the Danubian levies back to his standard while he completed the siege of Zeta. The shame-faced Danubians had allowed their lord Cerdic to be killed amongst them and fought hard throughout the rest of the campaign to erase the stigma of their failure. Edward was to use them as a cutting edge for his army, beating the Prince of Rashka and forcing a peace that also made him Earl of Zeta.

Two other events of note occurred after Edward became Prince. Firstly, he honoured his father’s pledge and awarded Eadgar (the Atheling) the Earldom of Ragusa. This meant the only Catholic province in the Theme was now ruled by a Catholic Earl. It also removed from court a man who believed his right to rule was greater than Edward’s. The Atheling clan were not to lose these ideas easily.

The second event was a liaison between Edward and a Serbian commoner during the Zeta campaign (1086). This resulted in the birth of Saebert Fitz-Uffason (Don’t ask me why we use a Norman style word to denote illegitimate bloodlines, we just do. Perhaps it started as a joke about the William the Bastard himself). Saebert should have been nothing but a mild embarrassment to the family, but instead was to imperil the legitimate succession (and the stability of the realm) for decades to come.

Occasionally we are all forced to do things to please our in-laws. In most cases this involves staying in some drafty hall, nodding politely while hearing how other family members have accrued more prestige and gold than you. In Cerdic’s case it involved declaring war on the Republic of Ragusa. This small merchant republic had been increasing its share of Adriatic trade and this had not been pleasing to the merchants of Venice, including Cerdic’s father-in-law Domenico.

In 1083 Cerdic brought the men of Epirus and the new Danubian Earldoms and besieged the city by land, while Domenico’s Venetians blockaded it by sea. The siege was successful, and largely uneventful but for one incident in the last week of the siege. Cerdic had been inspecting the siegeworks and had shed his chainmail because of the heat. Possibly Cerdic strayed too near the walls, or possibly the crossbowman fired the truest shot of his life, for a bolt cut Cerdic down, severely wounding him in the shoulder. While he eventually recovered most of the use of his arm, ill health was to dog him for the rest of his days, leaving him a grimmer, harder man. The new earldom of Ragusa served as poor recompense.

While some of the life had gone out of Cerdic, everyone could see the future in the form of his eldest son Edward. Despite his English name, Edward was truly one as the new breed of Cerdic’s Varangians. He spoke Greek as his first language, yet was fluent in the languages of his parents as well (English and Italian). He also had the polished manners and education that was expected in a Greek nobleman, being literate in Greek, Latin and (at his mother’s insistence) vulgar Italian. Like many second generation immigrants he spent his time swapping between different worlds (e.g. from the Varangian drinking hall to the Greek dining room), and became adept at managing the transformation. It was because of this ability that (in 1084) Cerdic raised Edward to become Earl of the most important part of the Theme – Epirus. Edward had been born and raised there and managed to govern the locals with far less trouble that Cerdic. Edward’s Greek credentials were further strengthened when he married Aikaterina Parapondylos, daughter of the Isaakios, Prince of Crete.

In 1085 Cerdic began plotting against Emperor Constantine XI. This was potentially a very dangerous move, yet Cerdic handled it with a political deftness that enabled him to simultaneously discredit the Emperor and secede from the Empire. The nature of this secession has been fiercely debated over the years. Some say that Cerdic was fully independent, others that his domains were still part of the Empire, but withheld their taxes. The facts that we know for sure are that in 1085, Cerdic began issuing his own coinage and stopped paying tax to Constantinople, but the Empire’s law still applied in his realm (as attested by various charters issued by Cerdic during the period).

If Cerdic showed shrewdness in his handling of the secession, he showed none in his relations with his new neighbour Vukan Vojislavljevic (the Count of Zeta and vassal of the Serbian Prince of Rashka). The two of them detested each other on sight, trading insults first in person and then by letter. By the middle of 1085 the border between Cerdic’s new Earldom of Ragusa and Vukan’s County of Zeta was a wasteland, stripped bare by raid and counter-raid. Cerdic’s reaction was to escalate the conflict and formally declared war. This was to be tough and evenly matched contest between Cerdic Prince of Wallachia and the combined forces of the Prince of Rashka and Count of Zeta.

The war started badly, as the Earldom of Turnu erupted into rebellion again, delaying Cerdic’s departure with the Danubian levies. This left Earl Edward to lead the Epirot and Ragusan levies alone. These performed creditably, driving off the Count of Zeta and besieging his strongholds. To build on this success, Cerdic led the Danubian levies directly against the lands of the Prince of Rashka. It was a strange battle that saw the Count of Zeta fleeing from Earl Edward, straight into the army of Prince Cerdic. It should have been a straightforward victory, and would have been had Cerdic not insisted on trying to personally cut a path through Count Vukan’s bodyguard to take the head of his adversary. Instead, it was Cerdic who was cut down (with a blow to the thigh) and bled to death on the field even as his huscarls went berserk and slaughtered the last of the Serbs.

How would the Theme of Wallachia react to the death of the man who created it? Would the soldiers follow the 17 year old Earl Edward Uffason, or chose a more experienced man to take the princely diadem? Edward responded confidently, like a young man who had been raised to rule his peers. He already held the loyalty of the levies from Epirus and Ragusa, and called the Danubian levies back to his standard while he completed the siege of Zeta. The shame-faced Danubians had allowed their lord Cerdic to be killed amongst them and fought hard throughout the rest of the campaign to erase the stigma of their failure. Edward was to use them as a cutting edge for his army, beating the Prince of Rashka and forcing a peace that also made him Earl of Zeta.

Two other events of note occurred after Edward became Prince. Firstly, he honoured his father’s pledge and awarded Eadgar (the Atheling) the Earldom of Ragusa. This meant the only Catholic province in the Theme was now ruled by a Catholic Earl. It also removed from court a man who believed his right to rule was greater than Edward’s. The Atheling clan were not to lose these ideas easily.

The second event was a liaison between Edward and a Serbian commoner during the Zeta campaign (1086). This resulted in the birth of Saebert Fitz-Uffason (Don’t ask me why we use a Norman style word to denote illegitimate bloodlines, we just do. Perhaps it started as a joke about the William the Bastard himself). Saebert should have been nothing but a mild embarrassment to the family, but instead was to imperil the legitimate succession (and the stability of the realm) for decades to come.

I'll make no comments about the injuries to your marshalls ... nice update and a hint at tumoult to come for your readers, at least, to look forward to.

Your power grows...

Did you award the earldom of Ragusa to Eadgar just for the sake of RP? Or was there another reason?

Did you award the earldom of Ragusa to Eadgar just for the sake of RP? Or was there another reason?

No strange emperors, although plenty of useless ones

Sounds like everything's proceeding as OTL then!

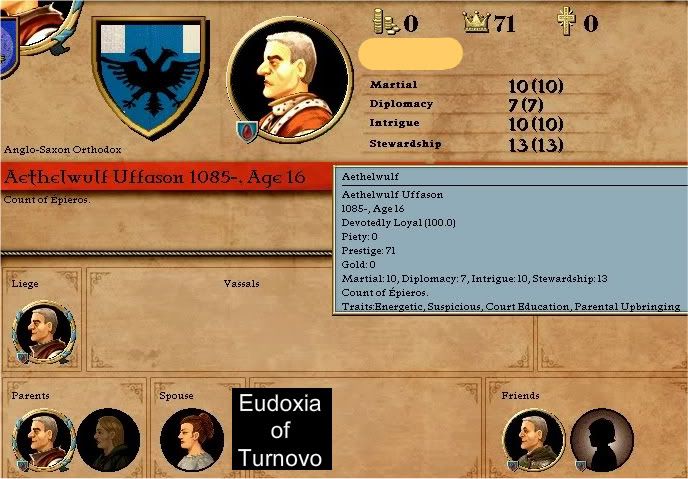

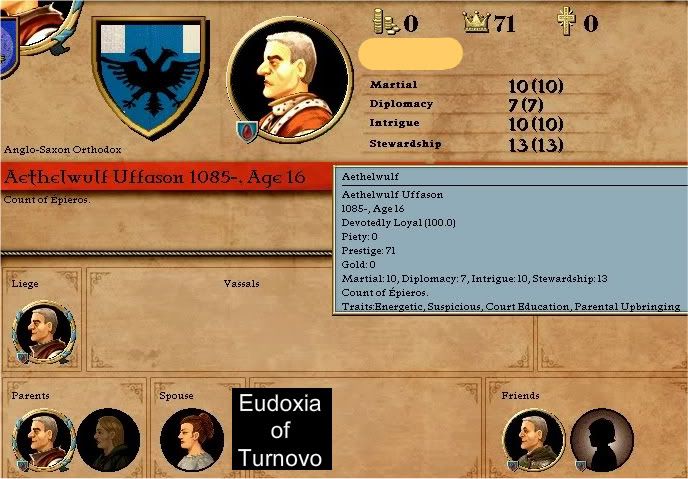

Cedric at least seemed to get the hang of Byzantine back-stabbing and betrayal by the end of his life - good for him. Edward seems promising (can we see his sheet?), despite setting himself up for a fratricidal struggle and a contest with the Aethelings. I'm looking forward to watching both from a safe distance

I'll make no comments about the injuries to your marshalls ... nice update and a hint at tumoult to come for your readers, at least, to look forward to.

It is a perilous occupation being a marshal. This worries me as I have been volunteered to be a fire-marshal at work.

Your power grows...

Did you award the earldom of Ragusa to Eadgar just for the sake of RP? Or was there another reason?

Just role-play really. However the realm is getting too big to manage without vassals, so it was useful.

Sounds like everything's proceeding as OTL then!

Cerdic at least seemed to get the hang of Byzantine back-stabbing and betrayal by the end of his life - good for him. Edward seems promising (can we see his sheet?), despite setting himself up for a fratricidal struggle and a contest with the Aethelings. I'm looking forward to watching both from a safe distance

I realised I was missing lots of the screenshots I needed from this period. I have gone back to the save file for one of Edward, but have struggled to get everything else I wanted.

Part 12 – The last Doukid Emperor, or Three Peaces (1088 to 1093)

Just as there are very few truly decisive battles, there are very few years that mark the end of an era of history. 1066 was such a year for the English. However, in the broader history of Christendom the Norman conquest was a peripheral event compared to outcome of the three great treaties of 1088.

Within the Theme of Wallachia 1088 started with an event that is not even a footnote in the broader spread of history. Prince Edward’s wife Aikaterina was due to give birth to their third child (the first two being Aethelwulf and Ulf). She was in sound health and had experienced no complications from her previous pregnancies. This time the labour was long and difficult. Aikaterina bled and bled, and Edward lost both her and his unborn child.

For a man with a noble and romantic heart, it seemed surprising that Edward remarried within the year. His new bride was Kyratsa Kourtikes, sister of Konstantinos, Prince of Achaia. This was a match he arranged with his head, not his heart, yet Kyratsa re-energised the court, sweeping away the sombreness that Aikaterina’s death had caused. He had made a better choice than he knew.

1088 also saw change at the Imperial court in Constantinople. Constantine XI died and was succeeded by his younger brother Andronikos. This was not good news for Edward, as Andronikos had previously been Count of Dyrrachion, which bordered Epirus. They had not been good neighbours, and (following a tirade of insults from Andronikos aimed at “foreign barbarians”) had sworn each other dead. This behaviour was a reflection of Andronikos’ unstable personality, angry and reckless one moment, and shy and sorrowful the next. Coupled with his rather modest talents as a ruler we can see that the blood of the Doukids was getting weaker with each ruler.

By 1088 the war against the Seljuks had been raging for 19 years and had bled the Empire white. While the Doukid Emperors had won battles against the Turks, these had not led to any strategic advantage. The Seljuks had just scattered, regrouped and returned to the fray. The Empire’s Anatolian heartland had been lost, and the Turks’ livestock grazed across the wasted ruins of what had once been fertile estates. Now the Seljuks had crossed to Europe and were outside the walls of Constantinople itself. Perhaps it was wisdom (rather than cowardice) that led Emperor Andronikos to seek a negotiated peace with the Seljuk Sultan.

Peace with honour would have been gratefully accepted by the Greek nobles as they awaited the negotiations. After all the Empire had seen off barbarians before. Surely the Sultan could be persuaded to leave Anatolia for a suitably large amount of gold. Finding the gold would be painful, but as this pain would be largely borne by the peasants and merchants it did not worry the nobility unduly.

The negotiations took place in the space between the great walls of Constantinople and the massed ranks of the Turkish host. Other than the Emperor and the Sultan only a handful of attendants were present. Emperor Andronikos offered his treasure, and a regular tribute once the Turks had left the Empire. The Sultan received this offer with a wry smile and replied that:

“Only one of us is in a position to dictate the terms of a peace settlement. I will keep what I have won in Anatolia, and you will give me Constantinople that I might have somewhere to rest when travelling this part of my domains. I will let you keep your crown, and will give you a night and a day to prepare your departure. Those are the terms of the agreement.”

Emperor Andronikos agreed and fled with his household to the island of Lesbos. He had just set about plotting how to hold together the European remnants of the Empire when the envoys of Nasr Ibn Marwan, the Emir of Edessa. The Emir’s forces had been far less successful than those of the Seljuks, but were far more powerful than anything Andronikos could call up to oppose them. They were also only a week’s sailing behind the emissaries. This time Andronikos could not even offer tribute, as the Turks had already taken everything from him. His will was broken and he collapsed to the floor as the shell of a man.

It was this remnant of an inferior emperor who met Emir Nasr of Edessa a week later. In exchange for a pension and a country estate Andronikos renounced the throne and named the Emir his successor. Nasr Ibn Marwan had become the first Muslim Emperor, heir to Augustus and Constantine. Nasr’s Empire was now split between his old stronghold of Syria and the remaining Imperial possessions in Europe. Had the Second Rome fallen completely, or was it being reborn?

Emperor Nasr certainly worked hard to consolidate his rule, touring his new European possessions and forcing the Christian princes of the Empire to acknowledge his supremacy. The one theme he did not visit was Wallachia. As you will recall, Prince Edward had refused to acknowledge the Doukid emperors since 1085, and did not plan to bow before a Muslim ruler.

In fact Edward was prepared to go further than simply not acknowledging Nasr as Emperor. In 1091 Edward declared war on Emperor Nasr. This might have seemed a futile attempt, as the resources available to the Emperor were far greater than those available to Edward. However, we must consider that Nasr was liked by very few in the core territories of the Empire, drawing most of his support from his old Syrian heartlands. I expect that Edward hoped the Greeks would rise against the infidel and flock to his banner. We should also consider Edward’s character. If he had been born a Frank they would have ranked him as the epitome of chivalric virtue. He was brave, romantic, and pious (reasonably so anyway). An all or nothing attempt to defeat a superior force of infidels and save the Empire and the Orthodox Church. This was what he had been born for.

Edward’s led a successful campaign, targeting counties held by the Emperor or his closest supporters. He marched first into the Empire’s Serbian territories, and then turned south for Thessalonike. Meanwhile, Earl Eadgar Atheling commanded a separate force that occupied Dyrrachion (on the Adriatic coast). However, none of the expected support for the Orthodox population materialised, and Edward soon found his forces being ground down in a series of punishing battles around Thessalonike. Edward won his battles, but was losing the war as more enemy contingents arrived from Syria.

Once more we see a face to face discussion between a Muslim victor and a weaker Christian ruler. This time the scene is set outside the walls of Thessalonike in the summer of 1092. Edward forced to swallow his pride and make a peace offer to Emperor Nasr. However, his bargaining position was stronger than Emperor Andronikos’ had been on Lesbos. Edward still had an unbeaten army in the field, and (although he did not know this) Nasr was very worried that the Greek rebellions might commence if the war were not ended very quickly.

Edward offered to pay homage to the Emperor and renounce (on behalf of both himself and his heirs) his claim to the Imperial throne. This was a huge sacrifice, and one that greatly diminished his prestige in the eyes of the outside world. However, Edward had devised a more subtle plan to resist the Emperor and proceeded to put it into effect as soon as the peace was signed. What did Edward gain from the peace? Well, he retained all of the land and vassals he had at the start of the war and kept the most important of his gains during the war. These were the new earldoms of Belgrade, Dyrrachion, and Thessalonike (where so much blood had been spilt resisting the Emperor). These gain left him significantly stronger and wealthier than when he had declared war.

By this point the direction of Nasr’s Roman Empire was becoming clear. While no organised repression of the Orthodox Church (and its steadfast believers) would occur, every preference would be given to Muslims in general and converts in particular. This gentle pressure produced a rash of conversions to Islam amongst the higher ranks of the Greek nobility. By the end of 1093 only three on the 13 nobles of princely rank within Nasr’s domain were Christian. Only the princes of the Aegean (who was soon to convert), Athens and Wallachia retained their faith, and Edward was by far the most powerful of these. Even more insidious was the conversion of the senior clergy. This saw all of the temporal bishoprics of the Empire (including the Archbishopric of Dyrrachion) being held by Greek Muslims.

The Empire had had its heart cut out as Constantinople had fallen to the Turks, and an Arab Muslim sat on the throne as supposed protector of the Church. Edward’s plan was simple, but subtle. He would build up an empire within the Empire. Thessalonike would be transformed into the centre of Greek cultural and religious activity. A capital for the Greeks under Muslim rule. While Thessalonike helped keep the flame of culture burning, Edward would work to expand his temporal power. This would be done under the guise of loyally serving the Emperor, and importantly would not break Edwards oath of fealty to the Emperor. Edward would work to make himself the foremost Greek Prince and would bide his time.

Greece would be like a bulb in winter. Hiding under the dark earth and waiting for Spring.

Just as there are very few truly decisive battles, there are very few years that mark the end of an era of history. 1066 was such a year for the English. However, in the broader history of Christendom the Norman conquest was a peripheral event compared to outcome of the three great treaties of 1088.

Within the Theme of Wallachia 1088 started with an event that is not even a footnote in the broader spread of history. Prince Edward’s wife Aikaterina was due to give birth to their third child (the first two being Aethelwulf and Ulf). She was in sound health and had experienced no complications from her previous pregnancies. This time the labour was long and difficult. Aikaterina bled and bled, and Edward lost both her and his unborn child.

For a man with a noble and romantic heart, it seemed surprising that Edward remarried within the year. His new bride was Kyratsa Kourtikes, sister of Konstantinos, Prince of Achaia. This was a match he arranged with his head, not his heart, yet Kyratsa re-energised the court, sweeping away the sombreness that Aikaterina’s death had caused. He had made a better choice than he knew.

1088 also saw change at the Imperial court in Constantinople. Constantine XI died and was succeeded by his younger brother Andronikos. This was not good news for Edward, as Andronikos had previously been Count of Dyrrachion, which bordered Epirus. They had not been good neighbours, and (following a tirade of insults from Andronikos aimed at “foreign barbarians”) had sworn each other dead. This behaviour was a reflection of Andronikos’ unstable personality, angry and reckless one moment, and shy and sorrowful the next. Coupled with his rather modest talents as a ruler we can see that the blood of the Doukids was getting weaker with each ruler.

By 1088 the war against the Seljuks had been raging for 19 years and had bled the Empire white. While the Doukid Emperors had won battles against the Turks, these had not led to any strategic advantage. The Seljuks had just scattered, regrouped and returned to the fray. The Empire’s Anatolian heartland had been lost, and the Turks’ livestock grazed across the wasted ruins of what had once been fertile estates. Now the Seljuks had crossed to Europe and were outside the walls of Constantinople itself. Perhaps it was wisdom (rather than cowardice) that led Emperor Andronikos to seek a negotiated peace with the Seljuk Sultan.

Peace with honour would have been gratefully accepted by the Greek nobles as they awaited the negotiations. After all the Empire had seen off barbarians before. Surely the Sultan could be persuaded to leave Anatolia for a suitably large amount of gold. Finding the gold would be painful, but as this pain would be largely borne by the peasants and merchants it did not worry the nobility unduly.

The negotiations took place in the space between the great walls of Constantinople and the massed ranks of the Turkish host. Other than the Emperor and the Sultan only a handful of attendants were present. Emperor Andronikos offered his treasure, and a regular tribute once the Turks had left the Empire. The Sultan received this offer with a wry smile and replied that:

“Only one of us is in a position to dictate the terms of a peace settlement. I will keep what I have won in Anatolia, and you will give me Constantinople that I might have somewhere to rest when travelling this part of my domains. I will let you keep your crown, and will give you a night and a day to prepare your departure. Those are the terms of the agreement.”

Emperor Andronikos agreed and fled with his household to the island of Lesbos. He had just set about plotting how to hold together the European remnants of the Empire when the envoys of Nasr Ibn Marwan, the Emir of Edessa. The Emir’s forces had been far less successful than those of the Seljuks, but were far more powerful than anything Andronikos could call up to oppose them. They were also only a week’s sailing behind the emissaries. This time Andronikos could not even offer tribute, as the Turks had already taken everything from him. His will was broken and he collapsed to the floor as the shell of a man.

It was this remnant of an inferior emperor who met Emir Nasr of Edessa a week later. In exchange for a pension and a country estate Andronikos renounced the throne and named the Emir his successor. Nasr Ibn Marwan had become the first Muslim Emperor, heir to Augustus and Constantine. Nasr’s Empire was now split between his old stronghold of Syria and the remaining Imperial possessions in Europe. Had the Second Rome fallen completely, or was it being reborn?

Emperor Nasr certainly worked hard to consolidate his rule, touring his new European possessions and forcing the Christian princes of the Empire to acknowledge his supremacy. The one theme he did not visit was Wallachia. As you will recall, Prince Edward had refused to acknowledge the Doukid emperors since 1085, and did not plan to bow before a Muslim ruler.

In fact Edward was prepared to go further than simply not acknowledging Nasr as Emperor. In 1091 Edward declared war on Emperor Nasr. This might have seemed a futile attempt, as the resources available to the Emperor were far greater than those available to Edward. However, we must consider that Nasr was liked by very few in the core territories of the Empire, drawing most of his support from his old Syrian heartlands. I expect that Edward hoped the Greeks would rise against the infidel and flock to his banner. We should also consider Edward’s character. If he had been born a Frank they would have ranked him as the epitome of chivalric virtue. He was brave, romantic, and pious (reasonably so anyway). An all or nothing attempt to defeat a superior force of infidels and save the Empire and the Orthodox Church. This was what he had been born for.

Edward’s led a successful campaign, targeting counties held by the Emperor or his closest supporters. He marched first into the Empire’s Serbian territories, and then turned south for Thessalonike. Meanwhile, Earl Eadgar Atheling commanded a separate force that occupied Dyrrachion (on the Adriatic coast). However, none of the expected support for the Orthodox population materialised, and Edward soon found his forces being ground down in a series of punishing battles around Thessalonike. Edward won his battles, but was losing the war as more enemy contingents arrived from Syria.

Once more we see a face to face discussion between a Muslim victor and a weaker Christian ruler. This time the scene is set outside the walls of Thessalonike in the summer of 1092. Edward forced to swallow his pride and make a peace offer to Emperor Nasr. However, his bargaining position was stronger than Emperor Andronikos’ had been on Lesbos. Edward still had an unbeaten army in the field, and (although he did not know this) Nasr was very worried that the Greek rebellions might commence if the war were not ended very quickly.

Edward offered to pay homage to the Emperor and renounce (on behalf of both himself and his heirs) his claim to the Imperial throne. This was a huge sacrifice, and one that greatly diminished his prestige in the eyes of the outside world. However, Edward had devised a more subtle plan to resist the Emperor and proceeded to put it into effect as soon as the peace was signed. What did Edward gain from the peace? Well, he retained all of the land and vassals he had at the start of the war and kept the most important of his gains during the war. These were the new earldoms of Belgrade, Dyrrachion, and Thessalonike (where so much blood had been spilt resisting the Emperor). These gain left him significantly stronger and wealthier than when he had declared war.

By this point the direction of Nasr’s Roman Empire was becoming clear. While no organised repression of the Orthodox Church (and its steadfast believers) would occur, every preference would be given to Muslims in general and converts in particular. This gentle pressure produced a rash of conversions to Islam amongst the higher ranks of the Greek nobility. By the end of 1093 only three on the 13 nobles of princely rank within Nasr’s domain were Christian. Only the princes of the Aegean (who was soon to convert), Athens and Wallachia retained their faith, and Edward was by far the most powerful of these. Even more insidious was the conversion of the senior clergy. This saw all of the temporal bishoprics of the Empire (including the Archbishopric of Dyrrachion) being held by Greek Muslims.

The Empire had had its heart cut out as Constantinople had fallen to the Turks, and an Arab Muslim sat on the throne as supposed protector of the Church. Edward’s plan was simple, but subtle. He would build up an empire within the Empire. Thessalonike would be transformed into the centre of Greek cultural and religious activity. A capital for the Greeks under Muslim rule. While Thessalonike helped keep the flame of culture burning, Edward would work to expand his temporal power. This would be done under the guise of loyally serving the Emperor, and importantly would not break Edwards oath of fealty to the Emperor. Edward would work to make himself the foremost Greek Prince and would bide his time.

Greece would be like a bulb in winter. Hiding under the dark earth and waiting for Spring.

well that was dramatic ... featuring a spectacularly incompetent Byzantine & Turks now ruling the City of Men (some 400 years early).

as to the rival -- well he's related and you've already indicated that the bastard half brother is to be a problem so I'll plump for Saebert?

as to the rival -- well he's related and you've already indicated that the bastard half brother is to be a problem so I'll plump for Saebert?

well that was dramatic ... featuring a spectacularly incompetent Byzantine & Turks now ruling the City of Men (some 400 years early)

Spectacularly incompetant is right. I had chosen to start Cerdic off with an Earldom on the Adriatic as I didn't want to do a crusading AAR. Within 20 years my Byzantine comfort blanket has fallen apart and (between the Turks and the Emperor Nasr) the whole Empire is in Muslim hands. I hadn't seen a Muslim Byzantine Emperor before in CK, so it was a bit of a shock. Lots of interesting possibilities though.

Muslim Rûm was rather unexpected... But looks very promising! Let's hope Edward succeeds in his goals!

Oh. It was so unusual I thought you had edited the save file. Maybe the Emir had gotten a "claim your neighbor's title" event, giving him a claim on the Imperial throne.

Oh. It was so unusual I thought you had edited the save file. Maybe the Emir had gotten a "claim your neighbor's title" event, giving him a claim on the Imperial throne.

That sounds plausible. I think Nasr's Emirate of Edessa bordered the Empire before the Turks swallowed Anatolia.

So much drama! Byzantions never fallen to Musilms in my games so early, usually it goes in late 1100s. Good luck with your plan, you already look incredibly powerful after your clash with the new Emperor

Hi all. This is a quick reminder that there is still time to vote in the AARland Choice Awards. Even if you normally prefer reading to commentating it is a good chance to show others what you are currently enjoying and to find some quality AARs that you might not have come across otherwise.

I am aimed (not entirely hopefully) to break last quarter's total of no votes for this AAR.

Part 13 coming up in a minute. (please say if you think there are too many screenshots this time).

I am aimed (not entirely hopefully) to break last quarter's total of no votes for this AAR.

Part 13 coming up in a minute. (please say if you think there are too many screenshots this time).

Last edited:

Part 13 – Life under the Muslim yoke (1094 to 1101)

Prince Edward lost no time in moving his capital to Thessalonike. Once there he began expanding the infrastructure of the city, renovating or building libraries and churches. At the insistence of his eldest son (Aethelwulf) he also built a new chamber for the city council to meet in. This was far bigger than required for the city’s councillors and some went so far as to say that it looked more suitable as the meeting place for the Imperial Senate than Thessalonike’s burghers.

The move to Thessalonike obviously agreed with Edward as it was only there that he really opened his heart to his second wife Kyratsa. They had been married for four years and had two children, but somehow it was only in Thessalonike that he saw how she had held his family together and brought him back to the world after the death of his first wife (Eudoxia). As the Prince feels, so does the court, and this period saw a flourishing of Greek love poems, as artists vied to Edward’s patronage. We will not even discuss the purported boost to fertility and potency that this atmosphere wrought.

While Edward was reforming the Greek south, he began to divest himself of his responsibilities in the Petcheneg provinces along the Danube. The first step of this was granting his illegitimate half-brother Swithelm the Earldom of Tirgoviste in 1094 (which included the former capital) and arranging for him to marry Zsannett, the daughter of the King of Hungary. Swithelm found himself transformed from an Uffason family embarrassment, to a member of the high nobility with a royal wife. Half-brothers do not always treat each other so kindly. The marriage of Swithelm and Zsannett is illustrative of the process by which the Uffasons sought to secure Christian allies and to legitimise their newfound princely status. This same policy saw Edward’s younger (legitimate) brother Oshere married to the daughter of Boris Duke of Croatia, and then made Earl of Turnu (also in the Danubian part of the Theme).

The Danube did not stay quiet for long however, as in 1095 Emperor Nasr declared war on the remaining Petcheneg Chieftains. Like a loyal vassal, Edward declared war at once. There were essentially two conflicts going on, as the Petchenegs sought to defend their lands, and the forces loyal to the Emperor and those loyal to Prince Edward sought to beat each other to the spoils of conquest. The war was bitterly fought, with victory going to the survivors of numerous small battles, not one decisive event. The cost to the Uffasons was great. They lost a great many men, including the Prince’s Marshal (captured, tortured, killed), and his (illegitimate) half-brother Oswald (killed in battle). They were however the overwhelming victors in this three way struggle, gaining the earldoms of Pereschen and Oleshye. The latter was to become increasingly important, as (again on Aethelwulf’s advice) Edward opened it up to settlement by Greek refugees fleeing Turkish controlled Anatolia.

This trickle of refugees was to become a flood, when in 1098 the Seljuks converted Constantinople to Islam. Almost by default, Edward had achieved his aim of making Thessalonike the centre of Orthodox Greek culture. If Greek farmers and soldiers went to take land-grants in Oleshye, the craftsmen and high nobility came to Thessalonike.

Also amongst those arriving in Thessalonike (1099) was Eustratios Doukas, son of Andronikos Doukas, the last Christian Emperor. Eustratios’ presence was useful in that it showed that Edward could harbour anyone he wished at court. Even someone who was a claimant to the Imperial throne. Eustratios’ arrival did present something of a challenge though. His father and Edward had been rivals, and by claiming the throne Eustratios also effectively claimed overlordship over Edward. Edward dealt with this in a similar way to how he had dealt with another potential overlord (Eadgar Atheling), which was with a marriage and a vow. In this case Eustratios was married to Edward’s younger sister (Aethelhild) and swore to become Edward’s client and serve as his marshal. It was understood that an earldom would follow in time. The use of the word client (rather than vassal) is interesting in this context. It is believed to be another of Aethelwulf’s innovations, drawing on Republican Roman practice (rather than Tribal Anglo-Scandinavian) to bind the Uffason’s new Greek subjects to them. It was far more palatable for these Greeks (who after all called themselves Romans) to follow civilised (if archaic) Roman practices, than current barbarian ones.

In 1100 the Theme of Wallachia was once more at war. This time Edward targeted the Greek apostate who ruled as Emir of the Aegean Islands. This war was very much a private enterprise, without Imperial sanction. However, what objection could the Emperor raise. Yes the Emir was a Muslim like him, but these islands had been part of the Empire since ancient times so a loyal Prince could consider it his duty to reclaim them. The war itself was noteworthy only because it was the first time the Uffason’s had taken to sea to fight a campaign. In this they were greatly helped by an influx of Greeks with naval experience from Constantinople. Edward added the earldom’s of Naxos and Euboia to the Theme, but could not take the Emir’s final possession (Lesbos), as the Emir chose to do homage to the Seljuk Sultan instead. While Edward had what might later be called a crusading spirit, conflict with the unstoppable Turks was no part of his plan.

1101 was a fortunate year for Prince Edward in a number of ways. Firstly he saw his eldest son (and heir) Aethelwulf come of age. Having an adult heir provided a measure of much needed stability, and reduced the chance of a war for the throne should Edward die. He wasted no time in marrying Aethelwulf to Eudoxia Kabakes, the sister of the neighbouring Prince of Turnovo (and daughter of the previous Prince) and making Aethelwulf Earl of Epirus. By giving Aethelwulf this particular earldom (which he had himself held), Edward was making it clear that his eldest son was also his heir. This may sound obvious, but in this part of the world primogeniture only really arrived with the Uffasons, replacing all sorts of more flexible (and often fatal) arrangements.

If harmony reigned between father and son in Thessalonike, it certainly did not do so at the Imperial court. Emperor Nasr I (who had seized the Imperial throne for Islam) had died in 1096, and was succeeded by his son Emperor Muhammad I. By 1101 Emperor Muhammad had so alienated his son and heir that young Caesar Muammar raised the standard of revolt against his father. It was a one sided contest and the result was never in doubt. The surprise came after Muhammad had seized Muammar’s last stronghold in Cyprus and had his son put to death in front of his assembled nobles and ministers. Muhammad may have thought that this would encourage the others, but it merely made him seem a tyrant, unworthy of an honourable man’s service.

Edward was regarded as an honourable man and decided to serve the tyrant no more. So in the Autumn of 1101 he withdrew from the Empire and began issuing his own coinage. Emperor Muhammad did not lift a finger to stop him.

Prince Edward lost no time in moving his capital to Thessalonike. Once there he began expanding the infrastructure of the city, renovating or building libraries and churches. At the insistence of his eldest son (Aethelwulf) he also built a new chamber for the city council to meet in. This was far bigger than required for the city’s councillors and some went so far as to say that it looked more suitable as the meeting place for the Imperial Senate than Thessalonike’s burghers.

The move to Thessalonike obviously agreed with Edward as it was only there that he really opened his heart to his second wife Kyratsa. They had been married for four years and had two children, but somehow it was only in Thessalonike that he saw how she had held his family together and brought him back to the world after the death of his first wife (Eudoxia). As the Prince feels, so does the court, and this period saw a flourishing of Greek love poems, as artists vied to Edward’s patronage. We will not even discuss the purported boost to fertility and potency that this atmosphere wrought.

While Edward was reforming the Greek south, he began to divest himself of his responsibilities in the Petcheneg provinces along the Danube. The first step of this was granting his illegitimate half-brother Swithelm the Earldom of Tirgoviste in 1094 (which included the former capital) and arranging for him to marry Zsannett, the daughter of the King of Hungary. Swithelm found himself transformed from an Uffason family embarrassment, to a member of the high nobility with a royal wife. Half-brothers do not always treat each other so kindly. The marriage of Swithelm and Zsannett is illustrative of the process by which the Uffasons sought to secure Christian allies and to legitimise their newfound princely status. This same policy saw Edward’s younger (legitimate) brother Oshere married to the daughter of Boris Duke of Croatia, and then made Earl of Turnu (also in the Danubian part of the Theme).

The Danube did not stay quiet for long however, as in 1095 Emperor Nasr declared war on the remaining Petcheneg Chieftains. Like a loyal vassal, Edward declared war at once. There were essentially two conflicts going on, as the Petchenegs sought to defend their lands, and the forces loyal to the Emperor and those loyal to Prince Edward sought to beat each other to the spoils of conquest. The war was bitterly fought, with victory going to the survivors of numerous small battles, not one decisive event. The cost to the Uffasons was great. They lost a great many men, including the Prince’s Marshal (captured, tortured, killed), and his (illegitimate) half-brother Oswald (killed in battle). They were however the overwhelming victors in this three way struggle, gaining the earldoms of Pereschen and Oleshye. The latter was to become increasingly important, as (again on Aethelwulf’s advice) Edward opened it up to settlement by Greek refugees fleeing Turkish controlled Anatolia.

This trickle of refugees was to become a flood, when in 1098 the Seljuks converted Constantinople to Islam. Almost by default, Edward had achieved his aim of making Thessalonike the centre of Orthodox Greek culture. If Greek farmers and soldiers went to take land-grants in Oleshye, the craftsmen and high nobility came to Thessalonike.

Also amongst those arriving in Thessalonike (1099) was Eustratios Doukas, son of Andronikos Doukas, the last Christian Emperor. Eustratios’ presence was useful in that it showed that Edward could harbour anyone he wished at court. Even someone who was a claimant to the Imperial throne. Eustratios’ arrival did present something of a challenge though. His father and Edward had been rivals, and by claiming the throne Eustratios also effectively claimed overlordship over Edward. Edward dealt with this in a similar way to how he had dealt with another potential overlord (Eadgar Atheling), which was with a marriage and a vow. In this case Eustratios was married to Edward’s younger sister (Aethelhild) and swore to become Edward’s client and serve as his marshal. It was understood that an earldom would follow in time. The use of the word client (rather than vassal) is interesting in this context. It is believed to be another of Aethelwulf’s innovations, drawing on Republican Roman practice (rather than Tribal Anglo-Scandinavian) to bind the Uffason’s new Greek subjects to them. It was far more palatable for these Greeks (who after all called themselves Romans) to follow civilised (if archaic) Roman practices, than current barbarian ones.

In 1100 the Theme of Wallachia was once more at war. This time Edward targeted the Greek apostate who ruled as Emir of the Aegean Islands. This war was very much a private enterprise, without Imperial sanction. However, what objection could the Emperor raise. Yes the Emir was a Muslim like him, but these islands had been part of the Empire since ancient times so a loyal Prince could consider it his duty to reclaim them. The war itself was noteworthy only because it was the first time the Uffason’s had taken to sea to fight a campaign. In this they were greatly helped by an influx of Greeks with naval experience from Constantinople. Edward added the earldom’s of Naxos and Euboia to the Theme, but could not take the Emir’s final possession (Lesbos), as the Emir chose to do homage to the Seljuk Sultan instead. While Edward had what might later be called a crusading spirit, conflict with the unstoppable Turks was no part of his plan.

1101 was a fortunate year for Prince Edward in a number of ways. Firstly he saw his eldest son (and heir) Aethelwulf come of age. Having an adult heir provided a measure of much needed stability, and reduced the chance of a war for the throne should Edward die. He wasted no time in marrying Aethelwulf to Eudoxia Kabakes, the sister of the neighbouring Prince of Turnovo (and daughter of the previous Prince) and making Aethelwulf Earl of Epirus. By giving Aethelwulf this particular earldom (which he had himself held), Edward was making it clear that his eldest son was also his heir. This may sound obvious, but in this part of the world primogeniture only really arrived with the Uffasons, replacing all sorts of more flexible (and often fatal) arrangements.

If harmony reigned between father and son in Thessalonike, it certainly did not do so at the Imperial court. Emperor Nasr I (who had seized the Imperial throne for Islam) had died in 1096, and was succeeded by his son Emperor Muhammad I. By 1101 Emperor Muhammad had so alienated his son and heir that young Caesar Muammar raised the standard of revolt against his father. It was a one sided contest and the result was never in doubt. The surprise came after Muhammad had seized Muammar’s last stronghold in Cyprus and had his son put to death in front of his assembled nobles and ministers. Muhammad may have thought that this would encourage the others, but it merely made him seem a tyrant, unworthy of an honourable man’s service.

Edward was regarded as an honourable man and decided to serve the tyrant no more. So in the Autumn of 1101 he withdrew from the Empire and began issuing his own coinage. Emperor Muhammad did not lift a finger to stop him.

its all going so well ... too well one muses? Really impressed with the death rate amongst your generals ... the mark of any well balanced CK kingdom.

its all going so well ... too well one muses? Really impressed with the death rate amongst your generals ... the mark of any well balanced CK kingdom.

They do their best. After all, how will people sing heroic songs about you if you die at home of gout.

So it begins!

Glad to see this back too!

RL quite busy (when is it not), so writing time is scarce.

This next update was going to be very short, but seems to have grown by itself.

Part 14 – What to do with freedom? (1102 to 1108)

After seven years yearning to be free of the rule of the Muslim Emperor’s, Prince Edward was now faced with a dilemma.

His realm was vulnerable because of its disparate nature. He held lands along the north bank of the Danube, a strip of land along the Adriatic, and a scattering of possessions in the Aegean. None of these were in a good position to help each other in time of war, especially the much feared war with the Empire, when Emperor Muhammad eventually decides to reassert control over the Theme. Indeed, the Imperial vassals that had provided the Uffasons with access to new lands to conquer now split the Theme into fragments.

Clearly then this was to be a period of consolidation, as Edward sought to strengthen the Theme within and without. The first sign of this strengthening was the permanent appointment of an Orthodox Bishop at court for the first time. Before this the Uffasons were not deemed important enough to warrant such special attention. Now with Constantinople in Turkish hands, the Patriarch was being less snobbish. Bishop Alexios was not a great theologian, but was able at least to add his dramatic flair to the chivalric culture that was evolving under Edward’s patronage. From now on the Uffasons’ armies would go to war with icons and great relics alongside their warbanner. Swords would be blessed and champions prayed for in the new churches of Thessalonike.

This was not a chivalrous culture as might be recognised by an Occitan Frank, but the concept is not so very far away. It combined the love of champions and epic song-poems from the homelands (England, Scandinavia, Baltic Shore, etc) of the Uffason’s Varangian nobles with the more refined courtly life of the Greek nobleman. Here we are already seeing the consequences of so much intermarriage between the Varangian incomers and the local Greek nobility. Many young Varangians at this point were half or three-quarter Greek by blood and had grown up surrounded by Greek servants and retainers. For these young Varangians it was necessary to invent an ideal of Anglo-Scandinavian warrior-nobility and then try to live it in practice. It is almost as if one can imagine the lowland Scots finally clearing out the Highlanders, and then dressing up in some sort of tartan costume for weddings, etc. Nevertheless, all cultures must start somewhere, and just as the Norman land-pirates in England were developing a new identity, the Uffason’s Varangian followers were becoming Helleno-Varangians.

In 1102 Edward also strengthened the realm by making his second son Ulf the Earl of Zeta (on the Adriatic). He then took a step which many at court found extremely distasteful, marrying Ulf to Mautild de Hautville, the sister of the Norman King Randulf of Sicily and daughter of King Roger (Borsa) who had conquered that land from the Moors. Was this a betrayal, or a piece of sensible diplomacy? Earl Aethelwulf of Epirus (Edward’s heir) thought the latter, and increasingly his views were heard at court:

“Why should I keep an enemy at my back, when I can have a brother-in-law there instead? Because his great-grandfather’s cousin may have fought my great-grandfather? Ridiculous. My Father [Prince Edward] has spoken, and if you do not like my new brother-in-law you can take your chances with the Turks or Arabs instead. They are the alternative. Now come and have a drink or bugger off and sulk elsewhere.”

Within the Empire all of the remaining princes had now converted to Islam by 1102. The bad news for the Orthodox world did not stop there, as the Seljuks sallied into the Caucasus and crushed the Kingdom of Georgia. The hurt of this was felt particularly strongly at court, as Earl Aethelwulf’s second wife Iya Bagratuni was a cousin of the King of Georgia. The Uffasons’ court saw an influx of Georgian nobles after this. They were welcomed by both Prince Edward (who was happy to help fellow Christians fleeing persecution) and Earl Aethelwulf (who knew that men with nothing of their own and no chance of going home can make loyal servants).

These servants had their first chance to prove themselves in 1103, when Georgios Palaiologos the Emir (since his apostasy) of Epirus seceded from the Empire. Georgios and Edward were longstanding rivals, just as their fathers had been. Without the Imperial shield to protect Emir Georgios, Edward declared war at once. He led the forces against the Emir’s mainland holdings himself, while Earl Aethelwulf led the seabourne attack on the Emir’s vassals in Corfu. The fighting was brief and ended well for Prince Edward (who gained the earldom of Arta, and vassalised Corfu), but less well for Emir Georgios (whose head ended up on a pike). Edward’s good humour at overturning this old rival meant that he allowed Georgios’ eight year old (Orthodox) grandson to remain as vassal Count of Corfu. Edward was now able to claim the title Prince of Epirus, and began referring to the whole realm as the Theme of Epirus, not the Theme of Wallachia.

In 1106 the Uffason’s took to sea again as Edward completed unfinished business with the Emir of the Aegean Islands. In 1100, they had been at war and the Emir had held onto the island of Lesbos by swearing fealty to the Seljuks. Now he had rebelled and was fair game. Edward set sail from Thessalonike with a large force, stormed the citadel at Lesbos, and set his bastard son Saebert up as Earl of Lesbos. As you will recall Saebert came from a liaison between Prince Edward and a Serbian commoner during the war of 1086 against the Count of Zeta. Young Saebert became a particular favourite of Prince Edward, so it was no surprise when he was granted an earldom. By this point we can see the three most important me in the realm for their generation – Earl Aethelwulf of Epirus (the heir to the throne), Earl Ulf of Zeta (the next in line), and Earl Saebert of Lesbos (a bastard, but favoured by his father, the Prince).

Two more good pieces of news reached the court this year. Firstly, the Seljuk Turks declared war on the Empire. If the enemy of your enemy is your friend, what happens when your two great enemies fight each other? Bad luck for them, and surely only good fortune for you. The second piece of news was that Norman rule in England had collapsed. After cursing William the Bastard and all his land-pirates for forty years they had finally fallen into fighting each other, and none of them were strong enough to rebuild the state. Rejoicing in this may seem bitter, but exile and the destruction of your whole class will do that to people, and these memories linger through the generations.

Prince Edward could be well-pleased when he surveyed the world in 1108. It was almost Michaelmas and he was calling his nobles together to feast and rejoice. Michaelmas was not really an Orthodox festival, but rather a tradition brought from the Uffasons’ Catholic origins and preserved as a special point in their year. On Michaelmas eve he retired to bed early telling his chamberlain that he felt unwell. Edward had enjoyed good health throughout his life, but had spent a lot of it on campaign and had been wounded many times. He also told the chamberlain that Bishop Alexios should make “the announcement” in the morning. On Michaelmas morning the chamberlain found Edward cold and dead in his bedchamber.

Bishop Alexios called a special mass for the court and made two announcements. Firstly he formally announced that Prince Edward was dead. Secondly, he brought forth a scroll bearing the seal of Prince Edward and the Patriarch himself. It declared Earl Saebert to be legitimate in the eyes of the Church and the Prince, leapfrogging Earl Ulf of Zeta to become second in line to the throne. Earl Aethelwulf had not been officially displaced as heir, but would he be able to take and hold the throne?

After seven years yearning to be free of the rule of the Muslim Emperor’s, Prince Edward was now faced with a dilemma.

His realm was vulnerable because of its disparate nature. He held lands along the north bank of the Danube, a strip of land along the Adriatic, and a scattering of possessions in the Aegean. None of these were in a good position to help each other in time of war, especially the much feared war with the Empire, when Emperor Muhammad eventually decides to reassert control over the Theme. Indeed, the Imperial vassals that had provided the Uffasons with access to new lands to conquer now split the Theme into fragments.

Clearly then this was to be a period of consolidation, as Edward sought to strengthen the Theme within and without. The first sign of this strengthening was the permanent appointment of an Orthodox Bishop at court for the first time. Before this the Uffasons were not deemed important enough to warrant such special attention. Now with Constantinople in Turkish hands, the Patriarch was being less snobbish. Bishop Alexios was not a great theologian, but was able at least to add his dramatic flair to the chivalric culture that was evolving under Edward’s patronage. From now on the Uffasons’ armies would go to war with icons and great relics alongside their warbanner. Swords would be blessed and champions prayed for in the new churches of Thessalonike.

This was not a chivalrous culture as might be recognised by an Occitan Frank, but the concept is not so very far away. It combined the love of champions and epic song-poems from the homelands (England, Scandinavia, Baltic Shore, etc) of the Uffason’s Varangian nobles with the more refined courtly life of the Greek nobleman. Here we are already seeing the consequences of so much intermarriage between the Varangian incomers and the local Greek nobility. Many young Varangians at this point were half or three-quarter Greek by blood and had grown up surrounded by Greek servants and retainers. For these young Varangians it was necessary to invent an ideal of Anglo-Scandinavian warrior-nobility and then try to live it in practice. It is almost as if one can imagine the lowland Scots finally clearing out the Highlanders, and then dressing up in some sort of tartan costume for weddings, etc. Nevertheless, all cultures must start somewhere, and just as the Norman land-pirates in England were developing a new identity, the Uffason’s Varangian followers were becoming Helleno-Varangians.

In 1102 Edward also strengthened the realm by making his second son Ulf the Earl of Zeta (on the Adriatic). He then took a step which many at court found extremely distasteful, marrying Ulf to Mautild de Hautville, the sister of the Norman King Randulf of Sicily and daughter of King Roger (Borsa) who had conquered that land from the Moors. Was this a betrayal, or a piece of sensible diplomacy? Earl Aethelwulf of Epirus (Edward’s heir) thought the latter, and increasingly his views were heard at court:

“Why should I keep an enemy at my back, when I can have a brother-in-law there instead? Because his great-grandfather’s cousin may have fought my great-grandfather? Ridiculous. My Father [Prince Edward] has spoken, and if you do not like my new brother-in-law you can take your chances with the Turks or Arabs instead. They are the alternative. Now come and have a drink or bugger off and sulk elsewhere.”

Within the Empire all of the remaining princes had now converted to Islam by 1102. The bad news for the Orthodox world did not stop there, as the Seljuks sallied into the Caucasus and crushed the Kingdom of Georgia. The hurt of this was felt particularly strongly at court, as Earl Aethelwulf’s second wife Iya Bagratuni was a cousin of the King of Georgia. The Uffasons’ court saw an influx of Georgian nobles after this. They were welcomed by both Prince Edward (who was happy to help fellow Christians fleeing persecution) and Earl Aethelwulf (who knew that men with nothing of their own and no chance of going home can make loyal servants).

These servants had their first chance to prove themselves in 1103, when Georgios Palaiologos the Emir (since his apostasy) of Epirus seceded from the Empire. Georgios and Edward were longstanding rivals, just as their fathers had been. Without the Imperial shield to protect Emir Georgios, Edward declared war at once. He led the forces against the Emir’s mainland holdings himself, while Earl Aethelwulf led the seabourne attack on the Emir’s vassals in Corfu. The fighting was brief and ended well for Prince Edward (who gained the earldom of Arta, and vassalised Corfu), but less well for Emir Georgios (whose head ended up on a pike). Edward’s good humour at overturning this old rival meant that he allowed Georgios’ eight year old (Orthodox) grandson to remain as vassal Count of Corfu. Edward was now able to claim the title Prince of Epirus, and began referring to the whole realm as the Theme of Epirus, not the Theme of Wallachia.

In 1106 the Uffason’s took to sea again as Edward completed unfinished business with the Emir of the Aegean Islands. In 1100, they had been at war and the Emir had held onto the island of Lesbos by swearing fealty to the Seljuks. Now he had rebelled and was fair game. Edward set sail from Thessalonike with a large force, stormed the citadel at Lesbos, and set his bastard son Saebert up as Earl of Lesbos. As you will recall Saebert came from a liaison between Prince Edward and a Serbian commoner during the war of 1086 against the Count of Zeta. Young Saebert became a particular favourite of Prince Edward, so it was no surprise when he was granted an earldom. By this point we can see the three most important me in the realm for their generation – Earl Aethelwulf of Epirus (the heir to the throne), Earl Ulf of Zeta (the next in line), and Earl Saebert of Lesbos (a bastard, but favoured by his father, the Prince).

Two more good pieces of news reached the court this year. Firstly, the Seljuk Turks declared war on the Empire. If the enemy of your enemy is your friend, what happens when your two great enemies fight each other? Bad luck for them, and surely only good fortune for you. The second piece of news was that Norman rule in England had collapsed. After cursing William the Bastard and all his land-pirates for forty years they had finally fallen into fighting each other, and none of them were strong enough to rebuild the state. Rejoicing in this may seem bitter, but exile and the destruction of your whole class will do that to people, and these memories linger through the generations.

Prince Edward could be well-pleased when he surveyed the world in 1108. It was almost Michaelmas and he was calling his nobles together to feast and rejoice. Michaelmas was not really an Orthodox festival, but rather a tradition brought from the Uffasons’ Catholic origins and preserved as a special point in their year. On Michaelmas eve he retired to bed early telling his chamberlain that he felt unwell. Edward had enjoyed good health throughout his life, but had spent a lot of it on campaign and had been wounded many times. He also told the chamberlain that Bishop Alexios should make “the announcement” in the morning. On Michaelmas morning the chamberlain found Edward cold and dead in his bedchamber.

Bishop Alexios called a special mass for the court and made two announcements. Firstly he formally announced that Prince Edward was dead. Secondly, he brought forth a scroll bearing the seal of Prince Edward and the Patriarch himself. It declared Earl Saebert to be legitimate in the eyes of the Church and the Prince, leapfrogging Earl Ulf of Zeta to become second in line to the throne. Earl Aethelwulf had not been officially displaced as heir, but would he be able to take and hold the throne?