Edge of Europe - A Belgian Interactive AAR

- Thread starter ThunderHawk3

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

((It's actually disgusting how much nepotism has infested itself into Belgian politics :laugh )

)

Modern Batavia

While the Pro-communist BDM took over in Batavia(the capital city in the Free State of Java) in 1967, their reign was anything but stable. The De Zoet's had plagued the Fascist-state, which led in the example of Abel William's entirely succesful, and fruitful dictatorship, which provided Java with civilization previously unseen in the Asian-Pacific. Modernizing the armed forces, and improving the standard of life slowly through the constant trinkle of wealth, it was no doubt that without his rebellion, Java would still be reeling from backwardness and tribal fighting as much as Africa is experiencing even in the modern age. While the communist believed and tried to sell to the world that their regime controlled the island, it was anything but. Their reign would last for three years, controlling the entire island, until French support began to wane as their colonial ambitions were faced with a de-imperalization, and the political struggles of Belgium and the fact that the closest port was thousands of miles off from anywhere near Batavia made them a little factor in a two-decade long war.

It started when soviet ambitions on the island furthered increased to try and kill off the rich, politically powerful dutch land owners, who for all intent and purposes still controlled the majority of all the trade and manpower of the island. They refused to leave their homes, and the communist regime's beaucratic process could do little to stop them behind their fortresses along the coast. When the soviet began trying to influence Batavia to take more extreme measures, encouraging active terrorism in exchange for wealth and power, so that they may lean more towards the sickle and the hammer.. The USA took a dangerous, covert operation to curb any such deal. It started with American smuggling of arms to Dutch-loyalist, then the propaganda programs started, the first light of the giant fire known as the Cold War. The United States would not have the communist control the most densely populated island in the world, as such they supported the Neo-Nazi movement known as the Dutch Guardsmen. The DG began an long drawn-out guerrilla war, plaguing populated centers, and even attacking Batavia herself on several occasions. Where their true power remained in however was in the forest of Java, where they build tunnels and bunkers, surprising any communist forces with secret-attacks.

These attacks were devastating to communist moral, however, their ideology did not allow them to falter especially with such heavy soviet backing. The conflict would rage throughout the island for a fourth of a century, various sides gaining the upperhand before quickly losing it again. Finally, when the USSR started liberalizing, they realized that the arms race they fought so hardly for could not continue. Liberal reforms and political collapse on the horizon, the USSR quickly pulled out most of its resources from the island, leaving it too become an mine-field for american capitalism to prevail. Fascist freedom-fighters and counter-revolutionaries quickly stormed the capital, the communist held strong however, and days of fighting led to the extermination of many government officials and the defacing and blacklisting of all records of Mayumi de Zoet and the De Zoet family. Tapestries of Abel Williams, and his personal insignia flew from the capital building for the first time in the last twenty years.

While communist forces still exist, even today in the island, much of the native population have simply accepted their fate as a conditioning of the fascist state into an isolationist policy of keeping only moderated media and information through. the Dutch have become more lenient on their xenophobia, however, native are still second-class citizens however and are treated as such, the prime change however is the addition of a psuedo-capitalism. With Americans supporting the prime restoration of the fascist government, the fascist respected american industrialist buying private property in the island, an act seldom ever seen before. They trade solely with America, allowing the american markets take first picks of all the bounties of the raw-materials that come from such a populated island, before selling it off at ludicrous rates. The Javan economy mostly reflected that of Mussolini's Italy, which viewed capitalism as an tool to use, rather then the enemy as they did in the past. They respected private property and private initiatives, although the state reserves the right to act whenever they see fit.

The fascist regime was forced to rescind their name, calling themselves reactionary 'nationalist'. The regime is a militarist junta, ruled by the generals who praise staying out of international politics and guarding their borders to the nail. They punish any and all communist activity, and it does not look as if much hope for the island to once again return to fully - democratic status, the communist movement dwindling as the youth are taught the strict principles of the 'nationalist'.

Last edited:

((For the record, the BDM weren't communists per se; just left-wing nationalists that favored the Soviets over the US. With Belgium having a somewhat strong anti-American streak and loathing anything resembling Abel Williams and the French also having a rocky relationship with the US and wanting to stick it to fascism, them backing them with at least material seems reasonable.

Other than that, looks good, even if the result makes me sad ))

))

Other than that, looks good, even if the result makes me sad

((For the record, the BDM weren't communists per se; just left-wing nationalists that favored the Soviets over the US. With Belgium having a somewhat strong anti-American streak and loathing anything resembling Abel Williams and the French also having a rocky relationship with the US and wanting to stick it to fascism, them backing them with at least material seems reasonable.

Other than that, looks good, even if the result makes me sad))

((Perhaps in the beginning, but after a while, the support teetered out. Added to that Belgian pacificst gaining ground, plus with their distance, I found it implausible they would have a large effect or even care enough to keep supporting them. Also, their communist to me and their communist to the soviets/USA!

And thank you, I didn't want to be a butt-head and shit on everything you made just because you posted it before my glorious post... Although, it added an interesting twist, even if it eventually failed. I liked it, thanks! hehe))

The Legacy of Dorijan Alain-Maaike van Cambille, the Vanished Belgian Bolshevik

During the Second World War, it has been chronicled by many Belgian historians that a small minority of Belgians, rather than falling along the Axis-Allies line, supported the Comintern. Along with resurrecting the Red Legion and the Walloon National Militia, many of these Communist-sympathizers fell in with a new group, founded by the seemingly ageless Dorijan Alain-Maaike Van Cambille. Returning from his post as a founding member of the Soviet KGB, Van Cambille organized a small but extremely violent resistance movement in Brussels during the war.

Van Cambille, however, died in 1942, choking to death on his cigar.

At the end of the Second World War, rather than disarming as most of the militias had, Van Cambille's cadets went to Spain as an armed, Soviet-backed military cadre. There, under the leadership of Van Cambille's adoptive son Marco Van Cambille, they carved out a territory in Basque Country. The Cambillez cadets- as they were called in Spain- were one of the more successful Socialist groups, defeating Franco's Falangists several times. At the same time, they sent numerous agents abroad to Africa, particularly to Congo-Brazzaville, attempting to overturn, by intrigue, the right-wing government in place there.

Van Cambille's cadets in Basque Country, plotting an attack.

Marco Van Cambille is pictured shirtless, on the left.

During the 1957 NATO intervention to end the civil war in Spain, Van Cambille's cadets conducted a vicious guerrilla campaign, finally ending pipe-bomb attacks in 1960. The Cambillez group then turned to politics, becoming a core element in Spain's left-wing coalition.

Van Cambille's Legacy, therefore, lives on in the modern-day Spain's Cambillez Party, the leading social-democratic political organization that has traded elections with the Conservatives in Spain since NATO intervention in 1957.

Van Cambille, although born a Walloon who pretended he was a Fleming, would end up being remembered fondly in Spain.

-

Ah, civilization.

You're such a bizarre little idea.

Why do we not all eat each other?

I do not know.

Jack.

:mellow:

Epilogues: The Others

Biographies of Notable Individuals

Biographies of Notable Individuals

Chodźko, Belloc

(1894-1975). Belgian writer, satirist, journalist, screenwriter, dramatist and political activist. Full name: Aldous Léonard Belloc Chodźko de Gesves. He is known for his early career as a writer of clever, witty satire and astute social and political commentary. Before the Second World War he moved to the USA, where he wrote numerous plays and screenplays, often in the style of the Theatre of the Absurd. He became an American citizen in 1960, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature 1962 and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1971. Notable literary works include Glory and Nothingness (1928), Stateless (1941) and The End of War (1957).

Saint-Cloud, Paul

(1879-1953). Belgian diplomat, liberal politician and solicitor. Served as Minister of Commerce (1913-1916), after which he moved to Sicily. He remained in Italy, practising as a solicitor, until his death in 1953.

Extracted from

Neon Living: The Life and Ideas of Belloc Chodźko

by Eric Westhoff

Neon Living: The Life and Ideas of Belloc Chodźko

by Eric Westhoff

Timeline

For part one of Chodźko's biography, covering the period between 1894-1939, click here.

[...]Arriving in New York City in late August 1939, Chodźko was largely unknown in the United States, having previously published only in the United Kingdom when writing in English (most of his novels had, by the start of the Second World War, been translated – either by a third party or by Chodźko himself.) He managed to secure a position first with The New York Times as a literary critic, writing under the name 'Léonard' (a pseudonym he had previously used when writing as a student) though stayed only until the spring of 1940, when he took a job with The New Yorker as an in-house satirist and correspondent on European affairs. Despite his previous desire to leave satire behind as a genre, he regarded the challenge of adapting to a new political climate as incentive enough to persist with the post. There was also a practical side to the decision, with Chodźko needing a means of income while he worked on establishing a literary presence in his new country.

His first publication in the U.S., and also his first work to be published primarily in the English language, was Summer in New York (1940), in which Chodźko detailed his journey from Europe to America against a backdrop of war and instability. While strictly a travel piece, Summer in New York is traditionally Chodźkoesque in that it places less of an emphasis on its subject (New York City) and more on the context, ideas and characters behind it – namely, portraying New York as a haven of peace against the mess across the Atlantic. The book sold respectably, and was also praised by critics, the vast majority of whom were unused to Chodźko's innovative style of travel writing.

Chodźko's first real success writing in the English language, however, came with the publication of Stateless in 1941. Inspired by the flight of the Belgian government to London following the Nazi invasion and subsequent occupation of the nation, the novel – his first for a decade – describes a world where all governments are stateless and move from polity to polity under the aegis of a supranational body in order to ward off stagnation. Selling out its original 5,000 copy within a month, Stateless, more than any of his later works, earned Chodźko his reputation (both commercial and critical) in United States.

Despite this success, he was not personally satisfied with the novel, feeling it too similar to his earlier work in terms of its themes and foci. He therefore committed himself to his work in order to try and discover a new muse other than the political stagnation he had left behind in Europe. The following year, in 1942, Chodźko would premier his first play in New York. The play, entitled Escaping Peace, follows a the story of a European émigré to the United States, and is largely autobiographical in nature. Escaping Peace also deals with deeper ideas than simple autobiography, however, discussing the apparent paradox faced by those leaving personal peace and stability at home for personal turmoil abroad – the paradox arising from the fact that 'home' may be wracked by turmoil and instability, whereas 'abroad' exists in peace.

The play ran for a fortnight in its original run, and was later reprised for a second run in 1943. It was also a critical success for Chodźko, with theatre critics praised both the acting and the writing, heralding the innovative and witty dialogue. Escaping Peace also marked Chodźko's first forays into dealing with existentialism and the human condition – having examined people's paradoxical nature of ruinous self-preservation – which would eventually lead him to be associated with such diverse and contemporaneous figures as Samuel Beckett and Albert Camus, though his first dramatic offering rests more in the tradition of the well made play than the Theatre of the Absurd.

Also during 1942, Chodźko published a short story via The New Yorker (also entitled The New Yorker) and a collection of verse – Words of War, a collection of witty, critical and pacific poetry composed during his time in America. The Predicament, another short story (and Chodźko's final published piece of short prose,) was published in 1944, though for the most part Chodźko remained quiet until the end of the war, having left New York to travel the United States in spring 1943. He returned to New York in 1944 to begin writing his next novel, A European in America, both an account of his travels and a critical look at the state of 'modern' American culture compared with the more established Continental tradition. The book was released in 1945, selling moderately well and generally achieving praise from critics.

Chodźko released his seventh novel, The Thinker, in 1946. It was his first since his breakthrough English language novel, Stateless, in 1941, and so was the subject of a considerable amount of anticipation and critical interest. When it arrived, however, the novel confounded readers. Serving less as a traditional novel and more as an extended monologue, The Thinker follows its central (and only real) character through one event – namely, his experience of an existential crisis after returning from war – and occurs over a timeframe of only a few hours. While many critics were appreciative of the thoughtfulness of the novel and praised Chodźko's daring, The Thinker was not a commercial success and was largely ignored by a book buying public who had come to expect more accessible work from the author. Nevertheless, The Thinker underwent a reappraisal when Chodźko's avant-garde streak became more widely accepted, and is now seen as one of his most seminal works – especially in relation to its position within the American modernist and post-modernist tradition.

Chodźko would return to the public's attention in 1947, when he premiered his second play on Broadway. Harmatia develops largely upon the styles first found in The Thinker focusing on a single subject as he endeavours to make sense of one incident – in this case, the titular 'harmatia', a fatal error of judgement by an unseen character affecting those few on stage in varied and profound ways. As the play develops over its two acts, the sparse cast take it in turns to ruminate on how their lives will change after the unseen lapse in judgement. Not one ever reaches a definite conclusion. Critics, now more used to Chodźko's apparent u-turn from popular humorist to avant-garde dramatist, were more receptive, though many remained sceptical of his decision to conduct such a change and a noticeable proportion of reviews for Harmatia were tolerant, if not praising. (One critic writing for The Boston Globe noted that: "Mr. Chodźko has run the full gamut of emotions in terms of what he has elicited from audiences over his career so far. Having gone from joy and excitement, we are now at impatience and boredom. I say he should quit before we reach indifference.")

1948's America As A Muse (a poetry collection) saw a return to the mainstream and a turn in fortunes for Chodźko, who had been hit financially by his recent forays into the avant-garde. The collection proved to critics and doubters that Chodźko was still able to command a sizeable audience, and had not taken leave of his formidable wit and aptitude for social commentary. Published during his ninth year in the United States, much of the verse within the collection takes as its subject the foibles of post-war society in the country. Praised as articulate and timely, it was generally well-received. America as a Muse was followed in 1950 by Chodźko's eighth novel, Life Postbellum, which centred around similar themes as his contemporary verse and highlights the paradoxical volatility that existed during what was ostensibly a peaceful time. Interestingly, the novel also brought Chodźko to the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee, who worried that his pacific and egalitarian leanings were a front for Communist sympathies, supposedly leading the FBI to compile an 800-page dossier on him. (Ultimately, he was deemed not to be a threat to the U.S.)

He made his return to the theatre in 1951, debuting Anagnorisis on Broadway in the summer. The play acts as a sequel to 1947's Harmatia, essentially picking up where it left off with the cast seeking to reach a conclusion as to how they will avoid the inevitable impacts of the 'harmatia'. Wittier and more accessible than its predecessor, Anagnorisis was more warmly received by both audiences and critics alike, with one reviewer in The New York Times noting after the play's opening night that: "now used to Mr. Chodźko's experimentation, the audience was patently more appreciative of his latest effort than his last outing on Broadway." A critic writing for Harper's Bazaar commented that "[Chodźko] has seemingly done the impossible in creating a play where the audience are left waiting for any action for the duration, and yet for the duration are glued to their seats." With its comedic dialogue and ability to merge both accessibility and the avant-garde, Anagnorisis has since been hailed as a masterpiece of modern drama and a seminal work within the Theatre of the Absurd. The play's debut also prompted a critical reevaluation of its predecessor, with Harmatia now also seen as a seminal work within the genre, if much less polished than its sequel.

Following the success of Anagnorisis, Chodźko moved to Paris briefly in the autumn of 1951. While there, he met Samuel Beckett, whose own En Attendant Godot was debuted in 1952. The two became good friends and exchanged ideas about future projects (though a mooted play cowritten by the pair was scrapped after the first drafts and survives only in fragments via Chodźko's notebooks.) Chodźko also took the opportunity to translate some of his more recent plays into French (notably Harmatia and Anagnorisis, which were also performed as one five-hour-long unabridged piece for the more tolerant Parisian audience.)

Chodźko returned to New York in 1953, publishing his ninth novel, Concessions to the Absurd almost immediately following his arrival. The novel is highly experimental, and by far the most avant-garde of his work outside of his late period output. It is also one of Chodźko's more post-modern works, making several clear references to the idea that the novel – as the title suggests – is merely a concession to the Absurd. He also took the opportunity in 1953 to apply for U.S. citizenship, though his application was repeatedly deferred as he refused to state that he would fight and die for the country due to his pacifist beliefs. The following year, he debuted what is generally as his most accessible play, Late to the Party, a satirical comedy about a writer who always finds himself late to the various movements he attempts to join.

Chodźko would spend the next two years in relative obscurity, focusing on writing and publishing little. He moved between Paris and New York in 1955, before returning to the U.S. to begin work on a series of experimental films, the first of which would be published as Experiment I in 1956, with another – Experiment II in 1957. They were never released in cinemas, however, and serve only as evidence of Chodźko's first forays into the world of filmmaking.

By contrast to this period, 1957 would prove a busy year for Chodźko. He published first Absurdity and Age, his final poetry collection, examining age and its place in society. (Chodźko, who was 63 at the time of its publication, was always somewhat resentful of his date of birth, feeling that being born in the 19th century prevented him from fully embracing the modern age.) The collection was well received, though largely overshadowed by his tenth novel, published in July: The End of War.

Chodźko in 1941.

The End of War is seen as a landmark piece in Chodźko's career as a writer. It is both his most profound book and his most successful; a book that would go on to define an era, and whose impact is felt still today. At its heart, The End of War is an optimistic book, one which gave hope to those who felt that the recent escalation of tension in Europe would lead to a Third World War (in this regard, it can be said that its timing was key to its impact) by hypothesising a scenario in which, as the title suggests, there is no war. The book, Chodźko tells the story of a man who, after suffering an existential crisis, renounces his place in society to focus on trying to inspire meaning in the lives of others – starting, he decides, by launching a crusade against that which does more to drain the world of meaning than anything else: war.

The book was a phenomenal success and, for the first time, introduced Chodźko to an entire global audience. It earned him widespread praise and plaudits, including from the Nobel Institute, which first put Chodźko on the shortlist for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957 (ultimately losing out to fellow Absurdist, Albert Camus.) Chodźko chose not to rest on his laurels, however, and debuted his fifth (and penultimate) play the next year. Walter's Ruminations marked Chodźko's return to the avant-garde following a relatively mainstream period, itself a two hour long near-monologue in which the eponymous Walter offers his (often often far-fetched) views on vaguely mentioned current affairs, punctuated occasionally by a passer by offering their own views. Intended as a subtle satire to highlight the abundance of would-be commentators in the modern media, the play was generally well reviewed, though was not as great a commercial success as many had expected, now being seen as a forgotten gem in Chodźko's repertoire. (A critically acclaimed film version from 1995 would later bring the play to the attention of a new audience and appreciative.)

Chodźko would not publish any work again until the 1960s, returning two years after Walter's Ruminations with his first proper film – an adaptation of his 1930 book Senseless in Java. The film was a commercial success, with many critics noting that the originality and filmic qualities of the book translated very well into film. The film was nominated for three Academy Awards (Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Art Direction (Colour) and Best Picture,) winning the first two. In stark contrast to this commercial success, Chodźko also published his eleventh novel in 1960 – Agents and Media, arguably his most post-modern and challenging piece of work, consisting of 273 pages of dialogue in which two characters discuss the role of characters in a novel as media by which an author can express his views. It was not a commercial success, though received praise from more tolerant critics.

The following year, Chodźko debuted what would be his final play, The Director, a post-modern comedy about a director's attempts to stage a play – in this case, the play itself. Critics were highly praising of the original premise, as well as Chodźko's witty script, and it performed well – eventually winning a status as his most accessible experiment with the post-modern. This success was followed in 1962 by Chodźko's twelfth novel, Looking For Work. Both of these releases, however, were overshadowed by the announcement that Chodźko had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature that year, following four years of being short listed since 1957.

Chodźko returned with another film in 1963, The Island, an adaptation of two of his early novels, Of Their Remedies (1924) and The Second Man (1926). Released in both the U.S. and Belgium, the film introduced his early work to a new audience and was followed by a period of renewed interest in his French-language work. The film was also nominated for two Academy Awards (Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Art Direction (Colour),) though won neither.

After his success in film, Chodźko returned to Belgium in 1964 for the first time since leaving 25 years earlier in 1939, before moving again to Paris. In Belgium, he was presented with the Belgian Film Critics Association's Grand Prix, which he had won for The Island the previous year. He returned to the U.S. in 1966, when he published his thirteenth (and penultimate) novel, Portrait of an Auteur, a semi-autobiographical look at a writer who branches out into film. Also in 1966, Chodźko finally was granted U.S. citizenship after thirteen years of having his application deferred. 1967 saw the release of his penultimate film, an adaptation of his 1928 novel Glory and Nothingness, which secured him a second Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

After a gap of 23 years, Chodźko surprised many by releasing a travel book in 1968. Simply entitled Travelling, the book offers his insights into and reflections on nearly 40 years worth of travels, as well as the changes to have occurred during that time. This was followed by a similarly themed film in 1969, Two Coats – Chodźko's final (and only wholly original) film – which documented a journey he had undertaken across the United States in the summer of that year, also examining many of the counter-culture elements active in the country at the time. It won Chodźko his penultimate Academy Award, that of Best Documentary.

Chodźko released his fourteenth and final novel in 1971, A Writer's Second Life. The book is split into two halves – the first and second parts of the writer's life (though the second comes first in the book) – and is told entirely from the point of view of those with whom the writer interacts, never dealing directly with his actions. It was reasonably successful. More prominently in 1971, however, Chodźko was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in honour of his prolonged and profound contribution to American literature.

A Writer's Second Life would ultimately prove to be Chodźko's final release. His output slowed down in the 1970s, with most of his projects after 1971 never leaving the draft stage. He died on the 29th of June 1975 at the age of 81, having never married. In his will, he stipulated that his ashes should be split between Brussels, Paris and New York. There are memorials to him in each city. In 1994, on the centenary of his birth, a literary festival was organised in his honour in Brussels, at which then-president Nicolas van der Wyngaert gave a speech hailing him as one of the most important writers of the modern age. In a poll conducted by Le Soir in 2003, he was named as Belgium's greatest ever writer.

Chodźko just before his death.

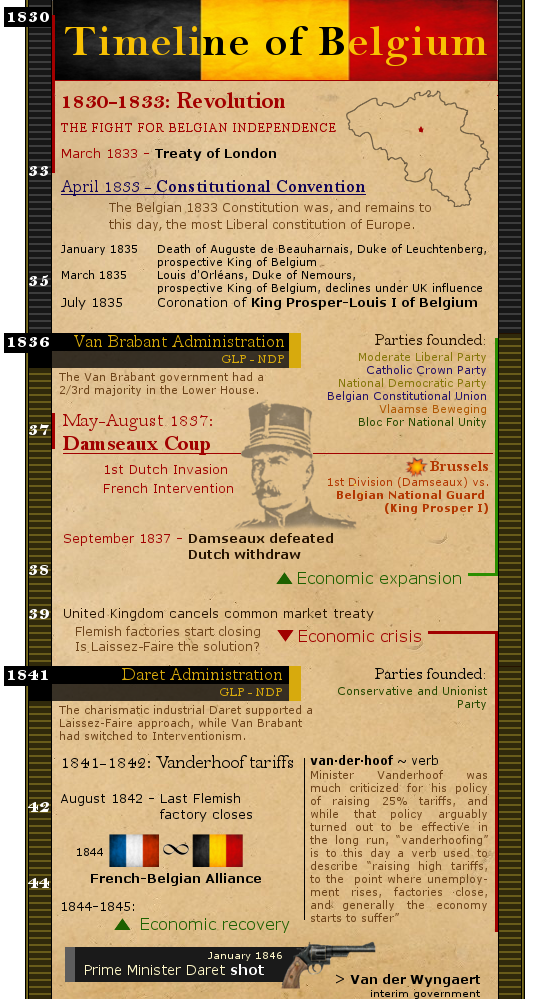

So... I stumbled onto some long, long overdue timeline I made when this was still up and running. I don't think I ever ended up posting it (if memory serves), so maybe some of you will enjoy this anyway

((Woah, that's cool! Did you ever finish it?))

((I'm afraid not. It took far too much effort and time to make