I suppose I’m mostly thinking about the very class-anxious, bourgeois foibles observational strain of comedy – but thinking about it that’s probably the next generation (Keeping Up Appearances and so on). I think you’re right for this period, that we’ll have a(n even) more pronounced anti-authoritarian tendency, probably smuggled in via a decent amount of surrealism. Not disimilar to what happened in Czechoslovakia after the Spring, for example.

Echoes of A New Tomorrow: Life after Revolution in the Commonwealth of Britain

- Thread starter DensleyBlair

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Threadmarks

View all 114 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Scenes from the Lewis caretaker ministry 1967 election: Press endorsements 1967 Election Results: 21:30 Thursday, May 4 1967 1967 Election Results: 07:00 Friday, May 5 1967 Make This Your Commonwealth: Lewis in coalition In Place of Strife: Lewis in the minority (Part One: A History of 'Common Beat') In Place of Strife: Lewis in the minority (Part Two: Red Autumn I) In Place of Strife: Lewis in the minority (Part Two: Red Autumn II)I’m waiting on “current events” to calm down a bit before putting up a fresh update, just because at the moment I get the sense the forum is pretty understandably occupied elsewhere atm. The next piece I’ve got lined up is a little tv bit about some of the stuff that’s been happening in France. In honesty, it’s mostly a filler to bring things like Algeria a little more up to date before the European Cold War blows its top, but hopefully not uninteresting. All being well I guess I’ll have it out by the end of the weekend?

In the meantime I’ve been taking a more detailed look at the structure for volume 2. It’s shaping up nicely, I think. Hopefully looking forward to some good discussions when we get there.

And I should also say thank you to everyone who voted for this work in the recent ACAs. I appreciate the support incredibly deeply, and it was actually my first outright win in an ACA round since 2015. So big love to you all.

In the meantime I’ve been taking a more detailed look at the structure for volume 2. It’s shaping up nicely, I think. Hopefully looking forward to some good discussions when we get there.

And I should also say thank you to everyone who voted for this work in the recent ACAs. I appreciate the support incredibly deeply, and it was actually my first outright win in an ACA round since 2015. So big love to you all.

The French Connection (Roland Barthes on the CBC, 1965)

THE FRENCH CONNECTION

INTERVIEW WITH ROLAND BARTHES

CBC 2, 1965

In the Commonwealth, as to much of the French public, the writer Roland Barthes is hardly known. Unlike the celebrated polemicist-philosophers of the Left, led by the duelling figures of Sartre and Camus, Barthes is an apolitical figure, who admires the Left from a studied distance. His work is almost uniquely on the language of mythology, and on the ‘science’, as he calls it, of signs and symbols. In the shadow of his titanic compatriots, Barthes – quieter, less readily accessible – has nevertheless created for himself a niche as one of the most compelling analysts of the Fourth Republic. I met with him to discuss Algeria, the Front de Gauche and the completion of the Eurotunnel.

I started by asking M. Barthes if he might give a brief opinion on the state of the Fourth Republic?

It is hard to make sweeping assessments of politics without tending towards grandeur, not to say grandiloquence. What seems likely is that the Republic is experiencing a period of transition. The passing of the former government of the Front Ouvrière in favour of M. Saillant’s Front de Gauche has granted a reprieve to the project of the Fourth Republic[1], which seemed certain to let itself burn upon the altar of the Jacobin principle. Our government is now less wedded to certain ideas of ‘common sense’ that persisted in spite of the Revolution, but the cost has been the expected one: we must now confront the deeply embedded reactionary tendency that survives within some groups of the French population.

Would you elaborate on this?

Suffice to say that any revolution, even one conducted by forces opposed to capitalism, cannot fully account for a complete overthrow of the old culture. Particularly not when the mythology of the Revolution is so integral to the radical French tradition. Thus we are able to reshape relations in our economy without examining other para-economic factor that support this relationship. Our culture remains heavily informed by the ideas of our grandparents’ time, which is to say there is a surviving culture of the petit-bourgeoisie. Even liberated from the yoke of profit, l’homme syndicaliste refuses to give up on a certain perception of himself: he is strong, worldly, dextrous; he satisfies himself with little beyond what is reasonable; he has attained a certain level of civilisation above and beyond men in other countries; he is most assured of himself when his fate is tied to the fate of the Republic. Belief in this type as ‘natural’ precludes any interrogation of what it means to live in France, against capitalism and imperialism and all sorts of other things.

But you have seen this too in Britain, so perhaps I do not need to explain so much.

In your opinion, then, has European syndicalism undergone something of a crisis in the past ten years or so?

Maybe it should not fall to me to make this assessment. I am not well enough informed.

But in broad terms as a man of the Left, you are not satisfied with the direction the Revolution has taken?

I was a very young man when the Revolution occurred, and I had only lately been introduced to modern literature thanks to the likes of Sartre. And so, in my youth, I did become quite attached to the language of the militant Left.

But I was never a militant myself, and I soon became suspicious of the language of Libération. It was far too sure of itself. I admire Sartre greatly, and I regard him as being one of our great writers, but I do not subscribe to the self-confidence of his position. I believe that elements of the Left have fallen into the bourgeois trap of holding themselves to be self-evident, which is to say what we mean when we describe things as ‘natural’. Naturalisation is a dangerous occupation, for it is the silencer of difference. My advice to the Left would be to accept that it is not natural. Not by any means.

Roland Barthes, writer and critic.

Do you see any signs of progress on this front following the defeat of the Front Ouvrière in the elections of 1963?

In the sense that this has allowed us as a collective to overcome our attachment to certain outdated ideas, yes. The argument unitaire is losing ground, which I am hopeful will allow for a more imaginative re-conception of the purpose of the Fourth Republic.

By this you refer to the troubles surrounding the withdrawal from Algeria?

Yes, and other things. The war in Algeria was merely the key that unlocked a bigger argument that needed to be had, about the foundation of the French state, about the reactionary Jacobin tradition that remains wedded to the heart of French radicalism.

What does this Jacobin tradition mean to you?

It means a perpetuation of centralised control; of the natural righteousness of the French radical tradition; of certain Enlightenment-era ideas about knowledge and virtue that refuse to die. It is the dominant means by which the French Left justifies its historical ascendancy.

Which might be taken as a roundabout way of describing the situation in Algeria?

Quite so. The French justification for remaining in Algeria, and indeed in all of its expropriated territories, is indistinguishable from the 19th century justification for going to Africa at all. The Revolution has become a new mission civilisatrice. Holding our own Left tradition to be founded upon incontrovertible doctrines of progressive science, it is as inconceivable to us that the Africans may reject our overtures as it was to the Catholic missionary that he would not be welcomed by the natives. This is why we refer to the events in Algeria as a ‘crisis’ and not a ‘war’, which would be more correct. We admit our lack of virtue once we start assigning things their true names.

The failure to uphold the Republican position in Algeria was a symbolic defeat for the whole project of the the Fourth Republic, which was founded upon an outdated conception of universality. We have been made to understand, at the point of a guerilla’s bayonet, that francité is not applicable equally in all contexts. Thus the central pillar of the French revolutionary tradition has fallen into jeopardy, and the Republic has experienced a death of the ego.

This is all rather pessimistic. Do you envisage a future for an internationalism that does not fall foul of these sorts of reactionary ideas?

Yes, it is quite simple: Europe must abandon her propensity for control, and she must accept that her mythologies – however benevolent she may believe them to be – are not universal.

What do you make of the United States’ critique of what it calls ‘Syndicalist imperialism’?

It would be valid, if it were not hypocritical.

Do you have anything to say about the influx of American culture onto the European mainland?

I am alarmed by it, but not surprised. Even after the affair in the Baltic during the winter, the United States is in no position to drive the anti-capitalist bloc out of Europe by force of arms; it is too far gone in the minority, and now that there has been a general rapprochement between the Syndicalists and the Soviets there is nowhere for the American bloc to turn.

Thus America has been forced towards a naked demonstration of its capitalism through pure cultural symbolism, which it hopes might permeate the European semiology with sufficient dexterity to subvert our rigid conceptions of the violence that capital perpetrates. It is a clever strategy; rock ’n’ roll will win more converts than the OAS.

pairing a bluesy instrumental with dark lyrics about sexual obsession.

Seeing as you mention OAS-Métro, what is your opinion of the suggestions that the United States government has been funding far-right terrorist groups in Algeria and in France?

I believe that these suggestions probably contain more than a little truth, although I personally can prove nothing.

In your view, is the completion of the Eurotunnel a cause for optimism?

Only a man with no soul could fail to be positive about the implications of such a thing. It is quite possible that with the Eurotunnel we are seeing a change in the mythology of engineering. The old equivalence of technological advancement with the demonstration of power has been overcome by a preference for the construction of new connectivities; despite the overall neomania of the project’s genesis, the Tunnel offers a great work that is useful to all, and expresses amity rather than adversity.

What is your attitude towards the Eurosyn more broadly?

Eurosyn gives us a framework within which the French people might reasonably agree amongst themselves on what it means to organise a French state. Casanova has been canny in this regard[2]; taking Kosygin’s visit as an endorsement of the Eurosyn has opened up space for the orthodox Left to overcome its scepticism of the Syndicate, on the basis that the Kremlin is not opposed to it. Thus there is an historic possibility finally to be rid of the Jacobin tendency within French radicalism; the Stalinists condemn themselves as reactionaries, and the modernisers appear all the more vital in comparison.

Finally, do you have anything to say about the situation in Britain?

I will leave Britain to her own trouble-makers.

_____________

1: Louis Saillant, leader of the Front de Gauche electoral coalition and Chairman of the Governing Council of France since 1963. He split from the Force Ouvrière during the Algerian Crisis to form the Union Syndicaliste, an internationalist party opposed to the unitarist Republican tradition.

2: Laurent Casanova, French Communist leader and one of the most prominent ‘Eurocommunists’ within the PCF. In the wake of Alexei Kosygin’s meeting with Eurosyn Chairman Maurice Fauré at Antibes in April 1964, the Eurocommunists developed a revisionist Communist tendency that emphasised communist organisation within the structures of the European Syndicate. This revisionism was described by Italian Communist premier Luigi Gallo-Longo (1964–66) as an ‘aggiornamento’: a ‘bringing things up to date’. In France, the tendency was opposed within the PCF by the anti-revisionist Thorezistes and the Jacobin Marchaisards, who remained sceptical of the Eurosyn.

- 2

You have perfectly captured all I expect from a French intellectual being given a fawning interview. It was uncanny, I could almost taste the Gauloises smoke and hear the clinking of the wine glasses.

Given the people all suffer from false consciousness and Jacobin obsession (why else would they not be enthusiastic worshippers of the state?) it is only when we lie to the people that we are virtuous?

Possibly one of the most depressing lines I've read in this story thus far.Barthes is an apolitical figure, who admires the Left from a studied distance

The French gotta French.The Revolution has become a new mission civilisatrice

If he said 'stop' I'd agree wholeheartedly. But as he said start there may be a deep philosophical socialist point I'm missing.We admit our lack of virtue once we start assigning things their true names.

Given the people all suffer from false consciousness and Jacobin obsession (why else would they not be enthusiastic worshippers of the state?) it is only when we lie to the people that we are virtuous?

The kind of sentence you can only utter if you know nothing absolutely nothing about engineering or engineers.It is quite possible that with the Eurotunnel we are seeing a change in the mythology of engineering.

- 1

You have perfectly captured all I expect from a French intellectual being given a fawning interview. It was uncanny, I could almost taste the Gauloises smoke and hear the clinking of the wine glasses.

You will recall I mentioned my second year last night over in Butterfly. Aside from the joys of learning the history of European housing since 1840 (good!) I was given a whistle stop introduction through a lot of French theory.

And, I won't lie, I do appreciate a decent amount of it, but my god is it easy to parody.

If he said 'stop' I'd agree wholeheartedly. But as he said start there may be a deep philosophical socialist point I'm missing.

Given the people all suffer from false consciousness and Jacobin obsession (why else would they not be enthusiastic worshippers of the state?) it is only when we lie to the people that we are virtuous?

His point is that the government are using euphemism to hedge what's going on in Algeria, so they're acting in bad faith. So it's not that by lying to the people they are are being virtuous, but that if the state were ever to say what it was doing with a straight face it would have to face up to the immorality of it all.

Not a particularly contentious point, I don't think. Just mixed up in some nice Barthesian pontificating.

The kind of sentence you can only utter if you know nothing absolutely nothing about engineering or engineers.

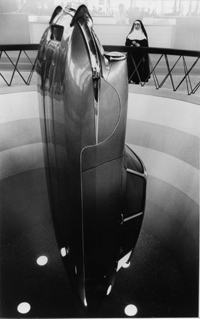

Have you ever read Barthes's ode to the Citroën DS? Lovely bit of engineering-as-rhapsody.

As a semiologist, I am almost certain that he knew virtually no engineers.

- 1

It does appear to be wilfully unclear. There is a sense of cloaking the obvious in jargon and bad phrasing, to increase the distance between the masses and the philosopher-priest dispensing wisdom. Sort of like the jargon used by boards and senior manageers at large companies, which is a comparison I'm sure both groups will find offensive.You will recall I mentioned my second year last night over in Butterfly. Aside from the joys of learning the history of European housing since 1840 (good!) I was given a whistle stop introduction through a lot of French theory.

And, I won't lie, I do appreciate a decent amount of it, but my god is it easy to parody.

Ah I see, that does indeed make sense. I had read it somewhat differently, probably because I had assumed the state was well aware of the immortality of their actions and didn't care. Or thought it was for the 'greater good', which is worse. Either way the use of true names or lies wouldn't matter to them, the euphemisms were for public consumption and there would be no great revelation on their part of the authorities if they stated things honestly.His point is that the government are using euphemism to hedge what's going on in Algeria, so they're acting in bad faith. So it's not that by lying to the people they are are being virtuous, but that if the state were ever to say what it was doing with a straight face it would have to face up to the immorality of it all.

Not a particularly contentious point, I don't think. Just mixed up in some nice Barthesian pontificating.

Certainly I think I agree with Barthes on the general thrust of his point, but perhaps differ on exactly who is deceiving who. But then you get into asking how much the person who believes and uses a government euphemism is fooling themselves, even if they know it is a euphemism. Which is almost certainly over-thinking things.

I had not and have just found a copy to read. He did have a way with words and it was a fun read, but alas (for him) his writing was not as incredible as the accompanying photo;Have you ever read Barthes's ode to the Citroën DS? Lovely bit of engineering-as-rhapsody.

A safe assumption.As a semiologist, I am almost certain that he knew virtually no engineers.

It does appear to be wilfully unclear. There is a sense of cloaking the obvious in jargon and bad phrasing, to increase the distance between the masses and the philosopher-priest dispensing wisdom.

I think this view is entirely understandable in hindsight, but I think generally theory makes more sense when you consider the fact that a lot of what we now hold as common sense comes thanks to the arduous hard work of people torturing out ideas in the 1930s and 40s. So now you read a lot of it and sort of think, Oh just get to the point. But the key thing is that the author may well have been the first person to actually reach the point, so obviously it's going to be harder work for them.

Just look at Judith Butler as an example. Gender Trouble is without doubt one of the most insightful books of the past century, but my god is it hard work – particularly when nowadays a lot of people are happy to accept that the gender binary isn't set in stone, and that sex, gender identity and gender expression are neither intrinsically related as functions, nor biologically defined. A few years later she wrote Bodies That Matter, which is a bit clearer, and then she kept writing a load of stuff which just got more and more clear. And this is as much because, a) she's obviously becoming a better communicator with practice, as it is that, b) the ideas are gaining currency so now it's not so tortuous a job to communicate them.

In this sense it's incredibly creative work, and the language sort of has to reflect that. Which means if you go into it hoping to read it like, say, history, it is maddening. But if you take it as something to work at it can be very rewarding.

Sort of like the jargon used by boards and senior manageers at large companies, which is a comparison I'm sure both groups will find offensive.

Yes, I think it's safe to say you've just offended a lot of company directors and critical theorists in one fell swoop.

Ah I see, that does indeed make sense. I had read it somewhat differently, probably because I had assumed the state was well aware of the immortality of their actions and didn't care. Or thought it was for the 'greater good', which is worse.

If you accept Barthes's assertion that they're all Jacobins, there's probably an element of 'greater good' in play.

Either way the use of true names or lies wouldn't matter to them, the euphemisms were for public consumption and there would be no great revelation on their part of the authorities if they stated things honestly.

It would be refreshing, mind.

Certainly I think I agree with Barthes on the general thrust of his point, but perhaps differ on exactly who is deceiving who. But then you get into asking how much the person who believes and uses a government euphemism is fooling themselves, even if they know it is a euphemism. Which is almost certainly over-thinking things.

Almost certainly, yes. Particularly for what is nominally a Vicky AAR.

I had not and have just found a copy to read. He did have a way with words and it was a fun read, but alas (for him) his writing was not as incredible as the accompanying photo;

Barthes is an excellent writer, so even if you don't really care too much for decoding what he's saying about signs and symbology it's never dull. But you are right, that picture is phenomenal. Where the hell has that nun come from?!

A very enjoyable perspective.

And really, who can blame him?I will leave Britain to her own trouble-makers.

A very enjoyable perspective.

Many thanks.

And really, who can blame him?

I’m glad to see this particular line getting picked up, I have to say. I was quite pleased with it

Some dubiously placed optimism about European disarmament from Bertrand Russell up next. Stay tuned.

Bertrand Russell on the Battle for the Test Ban

“BATTLE FOR THE TEST BAN”

FROM AUTOBIOGRAPHY

BERTRAND RUSSELL

1969

Between the years 1957–61, bookended at one side by the terrible tragedy at Windscale, and on the other by the long-overdue resignation of Oswald Mosley, no small number of us in the Anti-Nuclear movement set our hopes for securing a more peaceable approach to British international relations in the ascendancy of Aneurin Bevan and his allies in the Popular Front. Having memory of the work done by the original Popular Front of Stafford Cripps during the 1930s and ‘40s, it seemed to us not unlikely that our entry into the circles of the policymakers might best come through their successors. In particular, the return of the Independent Socialist Fenner Brockway to the forefront of the political debate, a veteran of the broad campaign for a just policy of international relations, gave a forceful and authoritative voice to the Anti-Nuclear opinion in the People’s Assembly in the aftermath of the Windscale fire. In addition to his work in championing the plight of the oppressed Kenyans suffering under the criminal Kenyatta regime, Brockway remained a steady representative of the movement for peace in its broadest sense, and in him, we had a great ally.

Aneurin Bevan had previously signalled his membership of the Anti-Nuclear movement, or at least his sympathies for our cause, and one on past occasion, before the action in Trafalgar Square over the Easter weekend of 1958, the combined leadership of the DAC-CND[1] had invited him to address the crowd on the subject of Britain’s nuclear deterrent. At that time Bevan was President of the Commonwealth, and thus perhaps considered himself bound by political fortunes not to accept our invitation, but in any event he did not come, and we were left to infer his stance from his opposition to Mosley, and from a long history of public statements given against the necessity of a British nuclear weapons programme.

Thus with Bevan’s accession to the Chairmanship in September 1961, those of us who had spent the last five years and more rallying against the British bomb were given some cause for optimism. So too were we hearted by the appointment of Fenner Brockway to the International Secretariat, which seemed to suggest, given Brockway’s decades of service to the cause of moral diplomacy, that the machismo and posturing that marked Mosley’s latter diplomacy (particularly evident after the dismissal of Philip Noel-Baker in 1954) was yesterday’s policy. No more would the Commonwealth stand for war, we thought; no longer would the politics of brinkmanship be supported; here at long last was the hour for peace!

Bertrand Russell, 1964.

In the first instance, those who favoured moral diplomacy were rewarded for placing their faith in the Bevanite tendency. Brockway was in government to fulfil one charge: to settle as justly as was practicable the relationship between Britain and her sister Commonwealths in the former Empire. He having grown up during the final years of Victoria’s reign, and having suffered as I did at the hands of the State for his strident opposition to the Great War, it was no doubt the crowning achievement to Brockway’s long career to see the effective end of the Empire brought about under his stewardship. Almost immediately, the International Secretariat announced that it would cease in its support of tyrants throughout the former colonies, and in particular a model settlement of the issue of land justice in Kenya was to be drafted at the earliest possible moment between the government and the opposition in Kenya, backed by British guarantee. Britain withdrew from its exploitative economic interests in Africa, and the Kikuyu and Maasai peoples were given back the fertile farmland which had been expropriated by British settlers over generations. (Those British expatriates who did not sympathise with the scheme of restitution, revealing themselves as would-be Rhodeses, quit for the more receptive climate of South Africa–Rhodesia, or else Australia; in all of these places, the settler ascendancy endured.)

The formation of the African Syndicate in June 1963 under Brockway’s guidance, led by the capable Dr. Nkrumah of Ghana, was an auspicious signal with which the promised new era of international good feelings may have begun. Indeed, coming only months after the final exit from power of Jomo Kenyatta in favour of his deputy Tom Mboya, and the completion of the power-sharing agreement with the KLFA under whose terms Dedan Kimathi took up the premiership, it seemed by all appearances as if the superannuated age of European colonialism had reached its sorry end. With great cause for celebration, I looked forward to the conclusion of efforts closer to home to resolve the many problems afflicting the European continent.

Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, President of Ghana, 1945–63.

Inaugural Chairman of the African Syndicate, 1963–68.

Chairman Nkrumah addresses the first congress of the Afrosyn, 1963.

Had one suggested at the start of 1964 that Europe, only eight years earlier wracked by the threat of open warfare for the first time in a generation, was moving towards a definitive era of peaceable relations, few onlookers would have thought this optimism unfounded, even if they may have been forced to admit that it reflected an especially sanguine outlook. Months before, the French Republic had confronted the implications of its shameful involvement in Algeria, and seemed committed to the final abandonment of the various outmoded principles that for so long had guided its opinion towards its Empire. Even the Capitalist bloc gave reasons for optimism; on March 31st 1964, the former Archduke Otto von Habsburg was elected as the first President of the Austrian Republic, free again from German rule after the redressal of the Anschluß of 1938, concluded months before the collapse of the Nazi regime. The following month, Soviet Deputy Premier Aleksei Kosygin travelled to Antibes, where he met with Maurice Faure, then the Chairman of the European Syndicate, in the most encouraging act of Soviet–Syndicalist diplomacy since the dissolution of the Pact Against Fascism in the 1940s, at the height of the Stalinist tyranny. All around, Europe seemed after a brief period of stupefaction to be crawling out from under the shadow of authoritarianism which had plagued the past three decades, and into a new existence lit by harmonious cohabitation.

Yet, outside of public view, a dark undercurrent built up during these years that threatened the viability of this new optimistic project. At the same time as in Britain we celebrated Mosley’s departure in 1961, in Berlin American State Secretary J. William Fulbright met with German Chancellor Klaus Bonhoeffer to discuss ways in which the German–American partnership might be solidified further. Behind this euphemistic language hid the true object of their discussions: the sanctioning of a US military presence in Germany, and in particular the introduction of American nuclear weapons to the European continent.

Secretary Fulbright, a staunch advocate for action on the European front.

Although Fulbright found Chancellor Bonhoeffer to be receptive to his proposals for military co-operation, so dogmatic was the anti-Communism shared by the two men that they were prepared to exploit any excuse for expanding the Cold War into new fronts, Bonhoeffer found resistance within his own cabinet from Foreign Minister Erich Ollenhauer, who was no less convinced of the necessity of the anti-Communist position than his two fellow statesmen, but who remained more wary of the global American imperialist presence. Ollenhauer’s great hope for the defence of the integrity of the Central European bloc, as he saw it, was the establishment of an endogenously European policy for collective defence. He was under no illusions about the extent of the United States’ goal of establishing a Weltpolitik, and foresaw a future in which the German Reich submitted itself to a position of pawnship under American hegemony. For a nation that had struggled with the assertion of its power in Europe for almost a century, giving over its defence programme so willingly to a new master across the Atlantic would not do.

But even Ollenhauer could not escape the influence of the prevailing opinions in Berlin, and in common with the majority of his comrade Cold Warriors in the Reich he was ever a student of the school of realism in political thought. There was one fact which Ollenhauer could not ignore: that Germany, sandwiched as it was in between rival powers, was furthermore the only one amongst this number not to possess an arsenal of nuclear weapons. This was not for want of ability; historically, the German capacity for both rocketry and nuclear science, the two component subjects of expertise required for the development of a bomb, is considerable. Yet since the dawn of the nuclear age in 1950, and after the arrival of the H-bomb in Europe with the European Syndicate’s acquisition of “Red Lion” in June 1959, Germany has been constrained by political will – not to mention raw geography – in its efforts to develop a testing programme.

Co-operation with the Americans therefore offered Ollenhauer what he most desired: a strong German defence policy, anchored by a nuclear programme that would give parity with the other European powers. As much as it may have ran contrary to his nature, and indeed his pride, gradually Ollenhauer was won over to the side of the Atlanticists. In March 1962, the Foreign Minister succeeded the ageing Chancellor Bonhoeffer at the head of government, and the following month it was he who hosted Secretary Fulbright for a second round of talks in Berlin. Washington would have its German missile programme, and in exchange for the Reich having some measure of autonomy in its management of the weapons – American-made “Thor” intermediate-range ballistic missiles – Berlin was to offer Austria its independence. The reversal of the Anschluß was pegged as the price for which Germany might buy its nuclear deterrent, and Ollenhauer could not refuse.

Erich Ollenhauer, 1962.

Chancellor Ollenhauer, in his eagerness to secure a nuclear future to Germany, was falling behind the times, and there is a sad irony to be found in the fact that Europe slid into its gravest nuclear confrontation following several years of optimism about a non-nuclear future. In the spring of 1962, Indian President S. Tagore made a speculative offer to broker a tripartite conference, between the United States, the Soviet Union and the European Syndicate, on the possibility of a global ban on the testing of nuclear weapons. Mistrust between the Soviets and the Americans killed any hope of President Tagore’s offer becoming a reality, and despite the intervention of the Anti-Nuclear movement on the ground in the Commonwealth, significant pressure could not be generated to force the matter through regardless. We would have to wait for two years until our hopes were reignited, when Deputy Premier Kosygin and Chairman Faure met at Antibes to discuss, amongst other topics, the introduction of a joint Soviet–Syndicalist testing ban.

Behind closed doors, the willingness of the leaders of the Cold War powers to keep up their defence of the nuclear option was fading. Bevan was not naturally inclined towards the nuclear deterrent, and prior to the assumption of Britain’s nuclear capacity by Eurosyn he had spoken in favour of unilateral disarmament. In Moscow, too, neither Khrushchev nor his First Deputy Kosygin were keen on maintaining the Soviet commitment to a vast nuclear programme, viewing it as an unnecessary and considerable expense on national resources. President Kefauver, who had long championed the rights of the consumer as an elected official, had prior to his election expressed concerns over the dangers of nuclear testing, particularly with regard to fears over the possibility of nuclear fallout leaching into the food supply. Had Kefauver not effectively delegated management of White House foreign policy to Mr. Fulbright, and to Vice-President Kennedy and his allies, the Soviets may have found Washington a far more congenial place to do business. In the event, President Kefauver’s death in August 1963 settled the balance in Washington in favour of the most intransigent camp of Cold Warriors. President Kennedy, more than any of his predecessors, took a firmly standoffish approach to US–Soviet diplomacy, and inspired in the Soviets a revival of the paranoid streak which had so troubled relations in the previous decade.

From Washington, Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin relayed a belief that Kennedy was fiercely ideological, and that his advisors were of weak character. Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko shared his ambassador’s low opinion of the new President, believing him to be out of touch and prone to contradiction. Gromyko, a fair-weather advocate of disarmament, held that the tide was turning against the possibility of securing warmer relations with the Americans. His task, as he saw it, was therefore to mitigate the threat posed by an even less co-operative White House. The logical option that remained open to him was détente with the Syndicalists in Western Europe, which would finally accomplish the isolation of Germany and her bloc on the European continent.

American PGM-17 Thor missiles arrive in Germany, 1963.

Over the winter of 1963–64, Soviet intelligence networks began to receive reports of German military manoeuvres. The quality of many of these reports were dubious, but their persistence raised an alarm in the Kremlin, and by February 1964 the Soviets had confirmed the existence of US-built missiles, transport vehicles and fuelling tents in German Pomerania. Two months later, Aleksei Kosygin shared this intelligence with Maurice Faure, who disclosed it in turn to each of the constituent governments of the European Syndicate. On the part of the Commonwealth, new International Secretary Bob Boothby (Fenner Brockway had retired after the election of 1963) adjudged that the American intrusion into Europe was an attempt to leverage a European withdrawal from the Americas; Washington had been looking uneasily to Cuba since the appearance of the revolutionary government in 1958, and similarly looked with distaste to Guyana, where the British maintained a strong interest.

The Europeans were reluctant, following this unprecedented American intervention into their affairs, to stoke further tension on the home front. Further, there was no appetite amongst the British to open up a new front in the Americas; to weaponise – literally – the Caribbean Commonwealths at the time would have flown in the face of the great strides made towards the disestablishment of the imperial network, and an arrangement with Dr. Cheddi Jagan’s new government in Guyana would have anyway represented only a notional threat to the United States. Only in Indochina was there the real possibility of Euro-syndicalist retaliation, and the increase in French support for their embattled former protégé Ho Chi Minh from 1964 onwards was no coincidence.

On the part of the Soviets, Gromyko was in favour of a response in Cuba; Khrushchev and Castro had reached an agreement for the installation of intermediate-range ballistic missiles on the island in February, shortly after the Soviets had confirmed their reports of American weapons in Germany. In April, days before the Antibes conference, the Soviet weapons reached Cuba, transported in secret via an elaborate game of maskirovka, or deception. I do not know whether Kosygin appraised Chairman Faure of the existence of the Cuban missiles during their April meeting, although in a subsequent cable from Khrushchev to the Eurosyn leadership the Soviet leader was open about his intention to confront the United States “with more than words”, possibly hinting at Soviet capabilities in the Americas.

Fidel Castro and Nikita Khrushchev drinking together in Georgia, 1963.

The public, however, knew none of this; the message to come from Antibes was one of optimism, and the promise of a rapprochement at long last between the Soviet Union and the European Syndicate. On the final day of Kosygin’s visit, our optimism was sealed by an historic public declaration: a joint commitment to talks on the implementation of a nuclear testing ban, as a first step towards disarmament in Europe, in lieu of a global agreement.

I wrote to Chairman Bevan immediately in the aftermath of this declaration by Kosygin and Faure, privately and in my capacity within the Anti-Nuclear movement, pressing upon him the importance of not letting the momentum in favour of disarmament relent until a worldwide testing ban could be secured, which included the United States. Some days later, Bevan responded publicly, stating that the British Commonwealth, in concert with her sister republics in Europe, had a moral duty to provide leadership in the movement towards disarmament. Further, he said that henceforth Britain wished only to use its knowledge of the power of the atom for peaceful means; she welcomed the approach by her Soviet friends to commit, together, to put an end to the devastating practice of nuclear testing in Europe, and expressed a hope that the United States would follow into an agreement. From Moscow, Khrushchev stated that the Soviet Union welcomed closer relations with her fraternal Socialist nations, and hoped to prove to the world the moral leadership that socialism offered.

In September, Soviet scientists and diplomats met with their Syndicalist counterparts in Cambridge, at the headquarters of the Nuclear Council of the European Syndicate (CNSE), to discuss the practical matters involved in drafting a comprehensive test ban treaty. I was invited to attend as an advisor to the British delegation. The talks took place at the CNSE building on Free School Lane, next to the Cavendish Laboratory. It amused me, having been dismissed in such scandal during the Great War, that I should return to Cambridge almost five decades later, party to a conference invested with the power to take the single greatest step towards peace I had known in my lifetime[2]. …

Khrushchev's deputy Alexei Kosygin in France, 1964.

On September 24th, the result of the talks were revealed to the world: the Soviet Union and the European Syndicate would commit, jointly, to observe a moratorium on the testing of all nuclear weapons for twelve months, beginning on March 31st 1965, pending the completion of a comprehensive bilateral test ban treaty. Yet our celebrations at having witnessed such a grand move towards disarmament, concluded between two of the premier powers of the Cold War, was tempered by the resurgent anxieties of the age. With the path to peace stretching ahead, Europe for the first time was made aware of the true nature of the threat she faced. Three days after the conclusion of the moratorium commitment in Cambridge, in a public statement Khrushchev declared the agreement a great victory for the future of Socialism. He went further:

The Soviet Government is opposed to recklessness in diplomacy, and it will not allow itself to be drawn in by the inflammatory actions of the United States of America, in concert with their allies in the German Reich. When we are met on our doorstep with the threat of war, the Soviet Union will do everything in its power to preserve peace. The question of war and peace is the most vital question of our age, and we must work tirelessly to remove the danger of unleashing thermonuclear war.[3]

The Soviet leader’s innuendo was made explicit shortly afterwards; a series of careful leaks saw Europe electrified in the autumn of 1964 by news of the American missile presence in Pomerania. Not for nothing had the Soviets retreated to their familiar paranoia over the American relation. The board had been prepared, and the gambit played; the Socialists had made their push for peace, and all eyes fell on Washington as she reacted to her newfound ‘moral isolation’.

_______________

1: DAC-CND, Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War–Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the two largest groups within the British Anti-Nuclear movement considered as one.

2: Russell is alluding to the fact that he was dismissed from his teaching post at Trinity College during the Great War, following his imprisonment as a pacifist.

3: Adapted from a letter from Khrushchev to Russell, 24 October 1961. Taken from Russell’s 1963 account of the Cuban Missile Crisis (and his role in diffusing it) Unarmed Victory.

- 2

Well played Soviets. Nice work

Reverse Cuba does leave things more favourable for Khrushchev – or at least, it's sort of easier to propagandise why they, in fact, are the aggrieved party. But with wily Jack Kennedy in the White House, things are far from set in place. Ho no.

Disappointing lack of teapots from Russell, but one can't have everything.

As always Russell reminds me of Kipling, in as much as you can always sense him mocking the uniforms that guard him while he sleeps. In fairness I'm sure he is mocking the concept not the men, but I've found military types do not make much distinction between the two. And in any event Orwell has it bang on "Those who 'abjure' violence can do so only because others are committing violence on their behalf."

EDIT:

I forgot to mention;

Excellent photo of Dr Nkrumah there, excitedly using his fingers to demonstrate exactly how many votes everyone else will be allowed once he has assumed power. The labels may change, but the actions remains strangely similar.

As always Russell reminds me of Kipling, in as much as you can always sense him mocking the uniforms that guard him while he sleeps. In fairness I'm sure he is mocking the concept not the men, but I've found military types do not make much distinction between the two. And in any event Orwell has it bang on "Those who 'abjure' violence can do so only because others are committing violence on their behalf."

EDIT:

I forgot to mention;

Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, President of Ghana, 1945–63.

Excellent photo of Dr Nkrumah there, excitedly using his fingers to demonstrate exactly how many votes everyone else will be allowed once he has assumed power. The labels may change, but the actions remains strangely similar.

Last edited:

Disappointing lack of teapots from Russell, but one can't have everything.

If you wish to suggest how the teapot might make it into the nuclear debate, we’re not done with Russell yet so there’s still plenty of game left.

As always Russell reminds me of Kipling, in as much as you can always sense him mocking the uniforms that guard him while he sleeps. In fairness I'm sure he is mocking the concept not the men, but I've found military types do not make much distinction between the two.

I think this is a little unfair. He wasn’t against violence as a matter of principle; he was (reluctantly) in favour of WWII and apparently once advocated for “preventative nuclear war” (whatever the hell that is) before the CND days. As I read it, it’s more of a moral opposition to forms of imperialist violence specifically, and then the disproportionate destructive capabilities of nuclear weapons.

But then he may well have also regarded the armed forces with scorn, I can’t say I know either way.

And in any event Orwell has it bang on "Those who 'abjure' violence can do so only because others are committing violence on their behalf."

For all of his flaws, our Eric did have a way with a good point.

Excellent photo of Dr Nkrumah there, excitedly using his fingers to demonstrate exactly how many votes everyone else will be allowed once he has assumed power. The labels may change, but the actions remains strangely similar.

Ho ho ho. Yes, it’s a good picture, isn’t it?

And, you’re right: the labels change but the actions are more or less repeated verbatim. Postcolonial leaders too historically speaking echo the colonisers, everything ends up in some awful singularity of state violence.

Recall that Nkrumah occupies a unique territory within this AAR as one of the few Mosley-era African leaders to have survived into the post-Mosley world, which he did by sort of pre-emptied Mosley’s African policy. As we head into the Sixties, an Nkrumah lead Afrosyn is certainly an intriguing prospect.

God, the first time you read Kipling's work and realise he wasn't joking...

Why he felt the need to write Tommy in eye dialect, one cannot begin to comprehend…

- 1

Actually, this Kipling talk has me thinking a little about the sort of 'left-wing' nationalism Billy Bragg et al try and kickstart every now and then. Maybe I'll give Kipling's legacy in the Commonwealth a look in volume 2. Might be interesting to consider as well what he got up between the war ending and the Revolution.

I think the problem with this "crisis" is quite simple: Germany is a rather more important state than Cuba. It will be interesting to see how that plays out.

As for Mr Russell, an interesting figure though somewhat "head in the clouds". After all, he and his cause has been played by the Soviets just as much as the USA.

As for Mr Russell, an interesting figure though somewhat "head in the clouds". After all, he and his cause has been played by the Soviets just as much as the USA.

I think the problem with this "crisis" is quite simple: Germany is a rather more important state than Cuba. It will be interesting to see how that plays out.

Maybe true, although I suppose nuclear weapons are a great equaliser in that regard. I’m not certain it’s any more natural for one to have them than the other – though no doubt it is hypocritical for the Soviets to be kicking up such a fuss.

As for Mr Russell, an interesting figure though somewhat "head in the clouds". After all, he and his cause has been played by the Soviets just as much as the USA.

Yes, and he is certainly no supporter of the Soviets. I think in this instance the fact that Khrushchev displays at least some willingness to negotiate tilts the balance in his favour slightly from Russell’s point of view. As we will also see a bit later, there is also the question of Russell’s considerable ego to take into account…

Just to note the lack of an update this week, the next piece (more Russell) is ready to go, but for scheduling reasons I’m holding off until @99KingHigh has completed his look at Vietnam and Indochina, which is more or less ready but just needs a few final touches.

In the meantime, if anyone wants to have a discussion about naval architecture, housing standards, British television or whisky vs whiskey or any such like, feel free to talk amongst yourselves.

In the meantime, if anyone wants to have a discussion about naval architecture, housing standards, British television or whisky vs whiskey or any such like, feel free to talk amongst yourselves.

Threadmarks

View all 114 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode