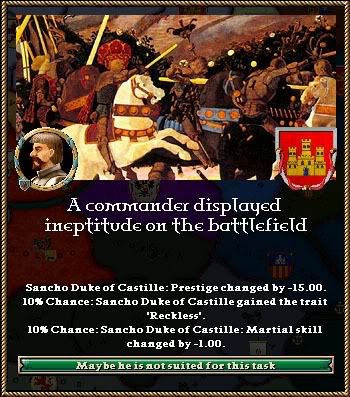

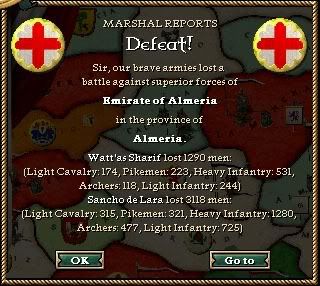

Ouch >_<

Also, an interesting fact I gleaned from a book I recently bought: Apparently one of Ferdinand Magellan's backers was from Haro. The book had this to say about the place:

Just happened to chance across it, and thought you might be interested

Also, an interesting fact I gleaned from a book I recently bought: Apparently one of Ferdinand Magellan's backers was from Haro. The book had this to say about the place:

"Haro (the city) flourished as a center of winemaking, and it also sheltered a community of Jewish goldsmiths and bankers until a civil war broke out in the fourteenth century and drove the Jews from their homes."

--Laurence Bergreen, Over the Edge of the World, New York: Harper Perennial, 2003.

Just happened to chance across it, and thought you might be interested