Contained herein is a brief treatment of the medieval

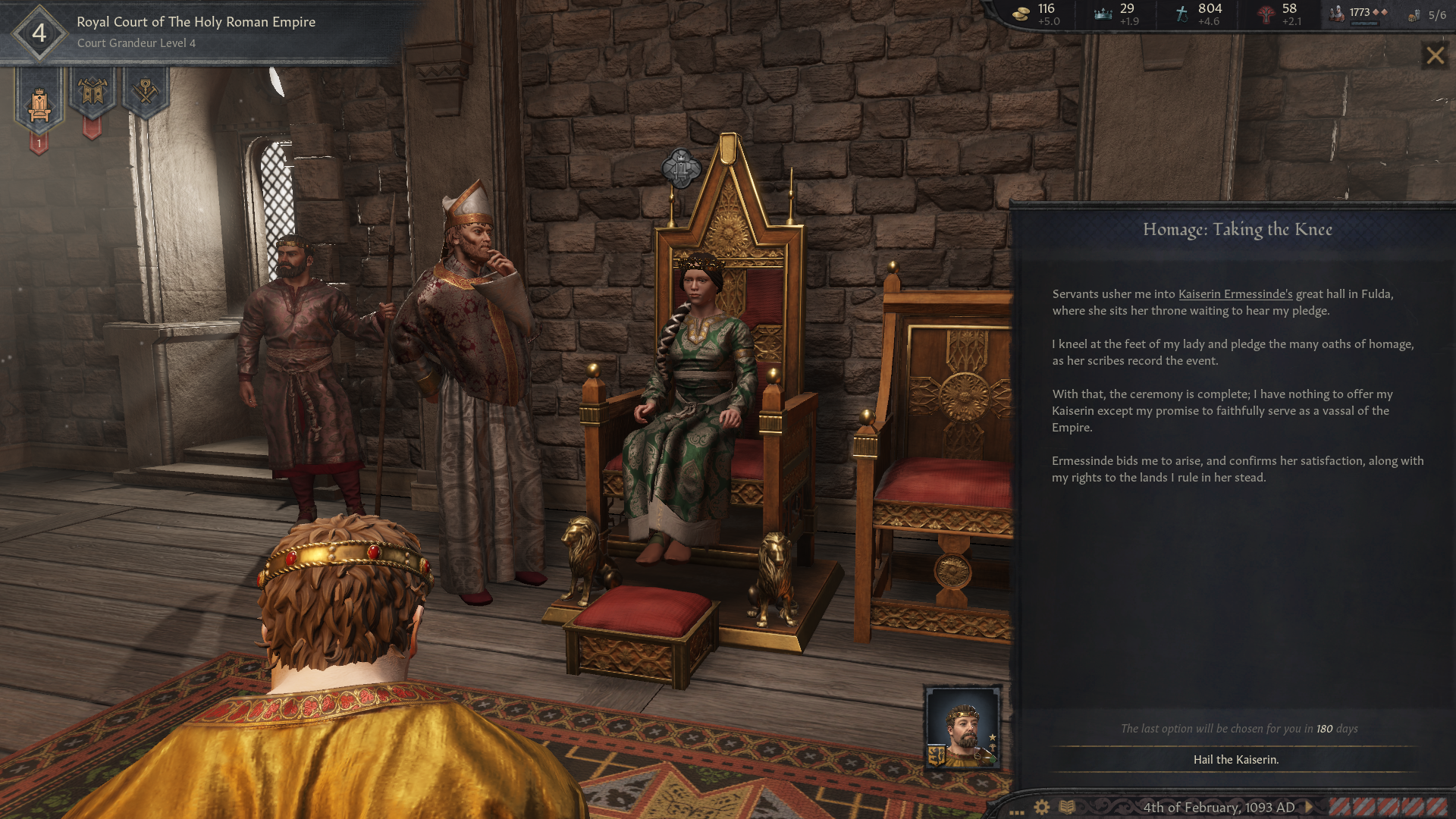

Fürstentum Obersachsen—that is to say in English, the Principality of Upper Saxony: the immediate predecessor to the Electorate of Saxony. Within the Holy Roman Empire, this principality was always something of an outlier, particularly when compared with principalities like Lothringen (the so-called

Mittelreich), Tirol, Baden, Bayern, Kärnten and Tecklenburg. In order to understand why an integral

Land within the Holy Roman Empire tied its fortunes to a coalition of eastern Baltic states beginning in the XV century, thus indelibly reshaping European history thereafter, we must first examine the roots of this Upper Saxon polity.

~~~

Upper Saxony has its roots in the X century Margraviates of Merseburg and particularly Meißen, which had been established by the Emperors of the Ottonian dynasty of the Holy Roman Empire as part of the

Saxon Eastern March. These, in turn, were carved out of the realm of Gero, who inherited it from his father Dietmar—who had been awarded with the newly-conquered Sorbian lands by Heinrich the Fowler. Somewhat roughly, this march covered a broad swathe of the hilly uplands between the right bank of the Elbe and the left bank of the Bober as it ran northward into the Oder.

After the death without issue of Gero, these lands were divided among various high members of the Saxon nobility. One part of the patrimony—the Margraviate of Merseburg—fell into the hands of a clan of Thuringian nobles, belonging to the Ekkeharding stem. The descendants of

Günther and his son

Ekkehard I of Meißen, Ekkehard and his family had been steadfast supporters of the young Emperor Otto III in his power struggle against Heinrich of Bayern, and took over in Otto’s name the defence of the eastern borders of the Empire in the wake of a Slavic uprising headed by the Lutician tribe.

One legend, recounted in the XIII-century Middle Saxon verse epic

Swartvlögel unde Witvlögel [preserved in High German as

Schwarzflügel und Weißflügel] has it that a certain bold, hathel Sorbian warrior named Vratislav was captured by the Saxons during precisely this Lutician Rising. He was forced to become a

jongleur performing for

Markgraf Ekkehard I’s amusement, and was given the epithet of

Dansâri as a result. Later this epithet was passed on as a surname to his Germanised descendants who came to rule Meißen and later the whole of Upper Saxony, who themselves turned it into a locative (Danzig, ‘of Gdańsk’) in order to distance themselves from this servile humiliation of their forebear

[1]. Whether or not this rather fanciful Late Antique legend is true, it does indeed illustrate one tendency of the Saxon ruling caste of the Eastern March: coopting and in some cases assimilating local Slavic warlords, whether by suasion or by force.

Upon the death of Ekkehard II of Meißen, the male line of the Ekkehardings went extinct, and the rule over the Margraviate of Meißen passed into the hands of the Weimar-Orlamünde stem: specifically, into the hands of

Markgraf Otto von Weimar. For a long time, Otto von Weimar had no male issue—his wife, Adela de Louvain, gave him only three daughters to start with: Oda, Kunigunde and Adelheidis. This lack of a son grew troublesome for the

Markgraf, and even as early as 1065,

Markgraf Dedo of the Ostmark had already been manœuvring to step in and attain for himself the Margraviate of Meißen.

He might have done this successfully, too… if Adela hadn’t given birth to a son and heir for her husband, in 1075

[2].

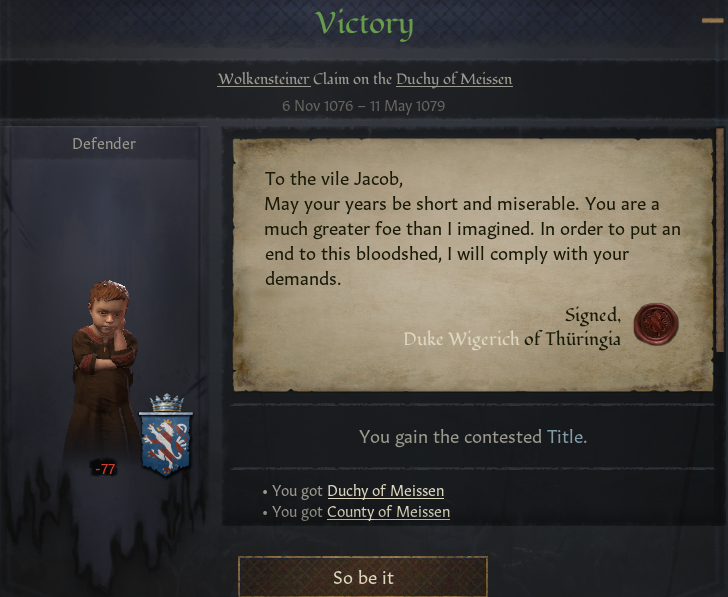

Wigerich von Weimar succeeded to the Margraviate of Meißen with the death of his father Otto, which happened the following year.

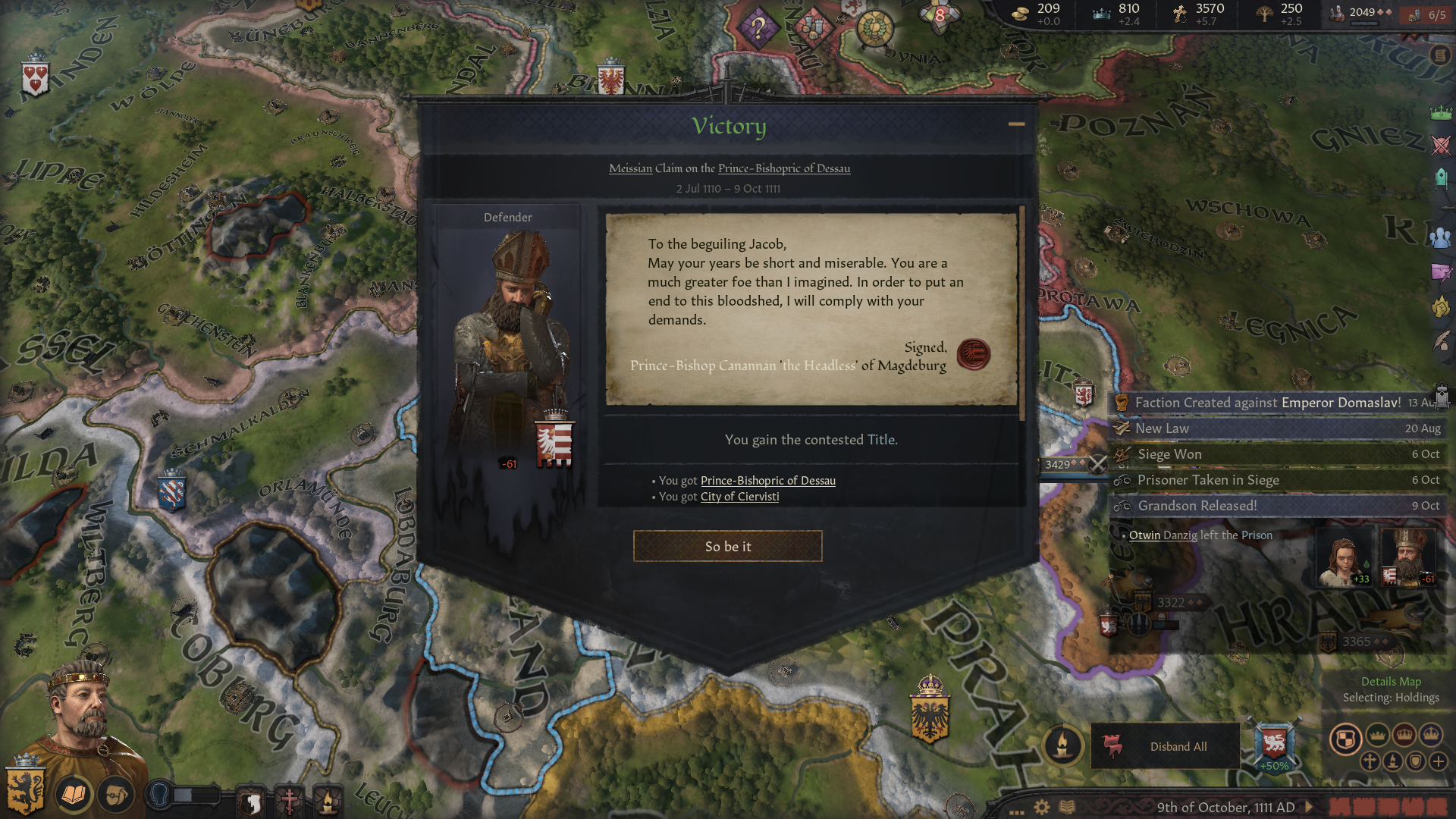

Wigerich’s reign over Meißen was brief. The baron (

Freiherr) of Wolkenstein and steward of Meißen,

Jakob von Danzig, made a successful appeal to the Pope that it was irresponsible to place the responsibility for such a key bastion on the edges of Christendom, in the hands of an infant… and the Holy Father of the Church agreed with him, and gave Jakob blessing to act as regent for the infant Wigerich until he came to majority.

However, as often happens during such regencies, Jakob, the supposed descendant of the fabled Vladislav

Dansâri, split the Weimar-Orlamünde patrimony neatly down the middle. He left Wigerich von Weimar in control of Orlamünde, and took the Margraviate of Meißen for himself. This happened in May of 1079. There was little that either the Pope in Rome, or the reigning Emperor Heinrich IV in Aachen, could do to redress this usurpation. By the time the news of it reached them, it was already a

fait accompli.

~~~

While he was still only a

Freiherr, Jakob von Danzig married

Mislava—a Dregovichian woman of one of the Slavic tribes comprising Turovian Rus’ [White Rus’], who hailed from an area near what is now Pinsk. Note that it was not uncommon for men in the

Ostmark or in Meißen to take Slavic wives. Even though the Saxons were very careful never to relinquish the reins of power in the lands under their sway, it was still common for Sorbs and Saxons to rub shoulders together… and occasionally more intimate parts. The fragmentary documents from this time refer to the usher of the court at Meißen by a Slavic name (‘Matziej’), and in addition there is a complaint from the local bishop (who also had a Slavic name, ‘Mscigniew’) of how common it was for Sorbian boys to fraternise with Saxon girls, leading them into fornication and robbing them of their virginity.

As for Mislava: to illustrate her character and how it was perceived locally, one may quote the German historian

Adam of Bremen, who likewise lived in the Margraviate of Meißen before his ecclesiastical transfer to Hamburg, and who was personally acquainted with both Jakob von Danzig and Mislava:

‘Sclavorum in Misnensi per mulierem eminentur exprimuntur: uxorem Iacobi Gedanensis. Haec matrona propter apstinentiæ et longanimatatem honorata est, sed tamen interdum garrulem ingenium exhibet rudibus vicinam. Bona femina, infaustum est quod Photii errorem sequitur[3].’

We may thus assume that Mislava was a woman devoted to the Byzantine Liturgy, and that she retained her devotion to Christ in the ‘Greek troth’ after she married. To Jakob, therefore, the East-West Schism was not only a great scandal upon the Body of Christ, but also a constant presence in his home life—a subject we shall return to in later chapters.

Another noteworthy thing about Jakob’s marriage to Mislava is how

prolific it was. Jakob von Danzig and Mislava’s marriage was both affectionate and abundant—even by the standards of the time. The two of them had

nineteen children together, whose names are all preserved in the

Schwarzflügel und Weißflügel: Alof, Älberto [Adalbert], Bisina, Christina, Þunar [Donar], Eilika [Helga], Folmar [Folkmar], Gertrud, Hengest, Isidor, Jakob

[4], Katharina, Liudulf, Meginhild [Matilda], Noþþa, Osgeri [Ansgar], Prämislawa

[5], Quonradus [Konrad] and Radigundis [Radegund]

[6]. If this leporine propagation of children were not convincing enough of their intimacy, the fragments of several letters between the two also contain such downright ribaldry as this:

‘

Hit freiþ mik, þet hlast þîna rîpa twêtala grenatappeln te dragan.’ (J to M)

[‘It makes me happy to carry the burden of your ripe pair of pomegranates.’]

‘

Blîþi bin ik, þat þî forþastar ast sprýtt êmêro kraftful und bald fora mik.’ (M to J)

[‘Lucky am I, that your foremost branch always sprouts vigorous and bold for me.’]

‘

Hwanne ik kêriu tehrug’, bin ik te þînan gard willikumo? Ik smako gerno þîna ferska lodika!’ (J to M)

[‘When I return, am I welcome in your garden? I love to taste your fresh wild lettuce!’]

‘

Hit havd giregant þârundar, þat te-lesan. Alsô þu nieht þâgegin hat, þat þê fûht ist: jâ, kum, et!’ (M to J)

[‘Reading that, it rained down there. If you have nothing against it being wet: yes, come, eat!’]

In addition, the fragments of the letters between the two attest touchingly to their shared interest in riddles, as well as to Mislava’s careful motherly attention in smartening up their son Älberto for potential future brides, and keeping Jakob’s estates and vassalage agreements in order. Although Jakob occasionally complained, in rather mild terms, about Mislava’s spendthrift habits, he never saw fit to remove from her any part of her responsibilities in the household. Though she was an East Slav and he a Saxon, their marriage seems to have been blessedly free of any serious conflict.

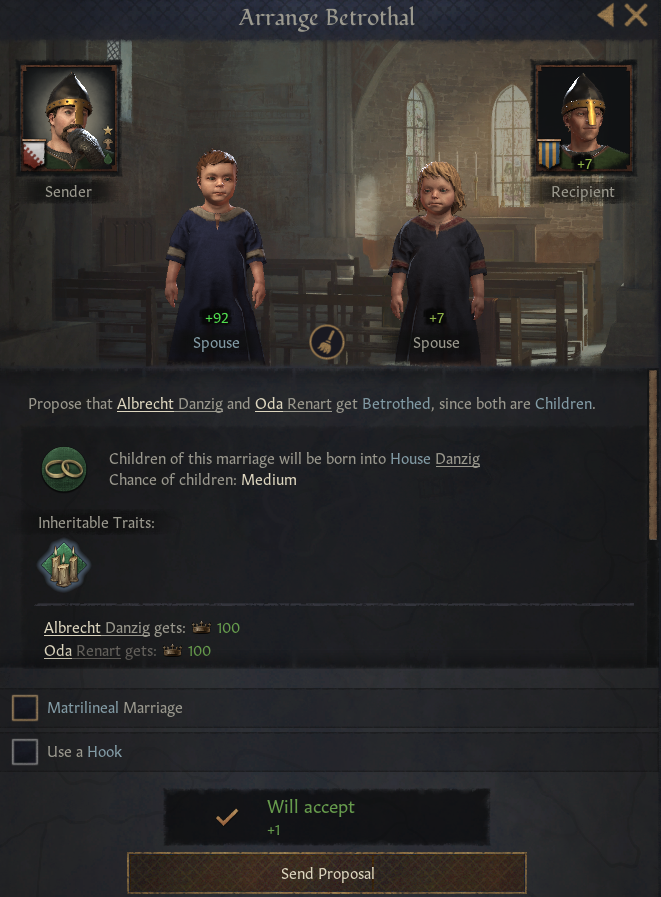

Despite fathering nine sons with Mislava, there was never any doubt in Jakob’s mind that his heir would be Älberto. It was also clear that he could play dynastic politics with the best of Saxon and Franconian nobility. The single most fateful and politically-astute act that Jakob made during his career was

not his swift usurpation of the Margraviate of Meißen from the Weimar line. It was to promise his heir Älberto in marriage to a certain Oda, the daughter of

Graf Otgar von Reynhard. This Oda would quickly come to be known as ‘

die Vixe’, or ‘the Vixen’: cunning, tenacious, hard-nosed, more than a tad unscrupulous. Jakob von Danzig must have recognised in her, even when she was only a child, a woman of keen sense and ruthless ambition who would make a valued and formidable ally… as indeed she proved to be.

Älberto was himself of quite a different temperament. He is described in

Swartvlögel unde Witvlögel as a consummate Christian: ‘

B’wigid fram luva for Christus wâri Älberto: Fora þe armer unde widuwen unde waisan wâri înna hand êmêro opan: Uvildâdarn gegin în hêld hî êmêro þe ôþara wanga hin: Unde þe list dir hôran orrêkian în niht.[7]’

To such a marriage of unlike people was the fortune of Meißen entrusted—and it was indeed, unlike that of Älberto’s parents, a troubled marriage. Without both Älberto’s and Oda’s talents, however, it is unlikely that the Upper Saxon principality would have knit together as soon or as smoothly as it ultimately did.

[1] It is particularly intriguing to note that

Swartvlögel unde Witvlögel was commissioned by

Fürst Ionathe von Danzig, who was given the epithet of ‘

Narrenfürst’ by his enemies. The tracing of the Danziger line to a similarly noble ancestor who was similarly degraded to the status of a court jester by an overbearing lord is more than likely meant to sympathetically reflect the tribulations of the king who commissioned the history.

[2] In another version of history, Otto von Weimar died in 1067, without male issue. The Margraviate of Meißen did indeed fall into the hands of Dedo I and his descendants… the Wettin family.

[3] ‘The Slavs in Meißen are notably represented by a woman, the wife of Jacob of Danzig. This lady was honoured for her self-control and long-suffering, though she exhibited a chatty temperament which sometimes bordered on rudeness. A good woman, it is unfortunate that she follows the error of Photius.’

Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum, addendum 12.1.

[4] Usually referred to by his pet-name of

Kopiki or

Köpke.

[5] The name of this seventeenth daughter has led some scholars to question whether or not Jakob’s wife’s name was actually also

Premyslava, of which the form which survives is perhaps a pet-name.

[6] It is uncertain what led Jakob and Mislava to name all of their children in alphabetical order.

[7] ‘Moved by love of Christ was Älberto. For the poor, the widow and the orphan was his hand always open. To those who did evil against him he turned always the other cheek. And the wiles of loose women touched him not.’