Haha!I probably am obsessing too much on research, which is a side effect of my having next to zero, and I do mean zero, idea of how most technical stuff works. And of my being fully aware of the fact. As a result, many a writing session has turned into a sterile hour of research while my inner writer and my inner nit-picker fight to the death.

The current update I'm working on is a textbook example, as I spent unreasonable time trying to figure out 1) whether I should write 'von Leeb' or 'Leeb' in a dialog involving two German officers (I'm going to use the French rule on that) 2) what altitude would a Henschel 126 fly at for recon mission and 3) whether the observer in said Hs-126 could swivel the camera around or not during the mission.

The somewhat good news is, writer and nitpicker came to a workable arrangement and the first of the two 2C updates should be churned up soon-ish (7 pages written, 3 or 4 more to go)

Crossfires, a French AAR for HoI2 Doomsday

- Thread starter unmerged(61296)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alright! I've done my september chores and I finally have some spare time to WRITE FOR FUN! I've added a couple of pages and hopefully will update tris weekend.

CHAPTER 123 – CASE WHITE

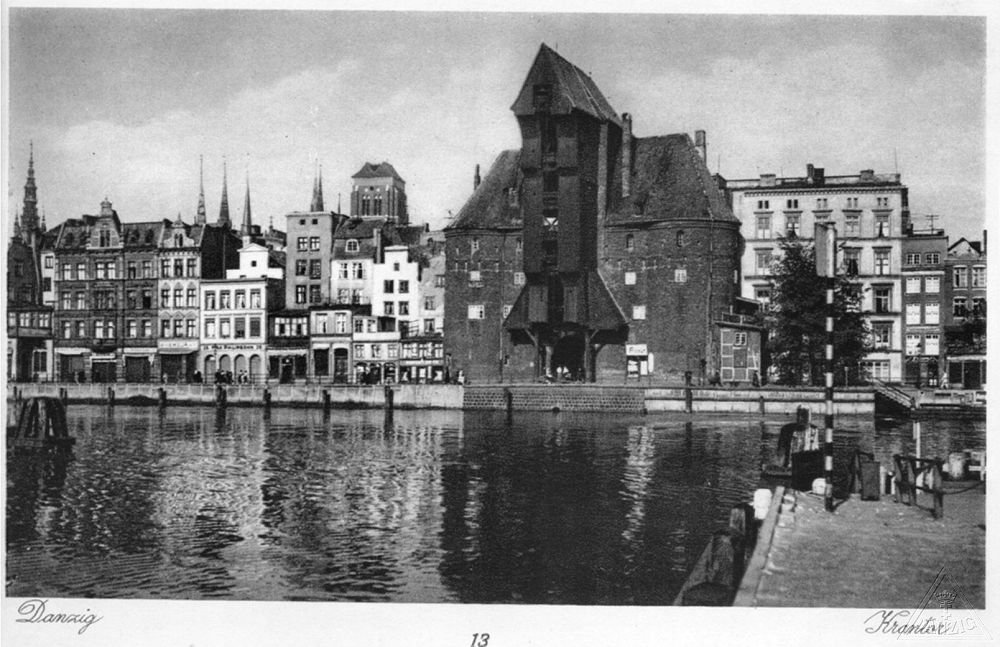

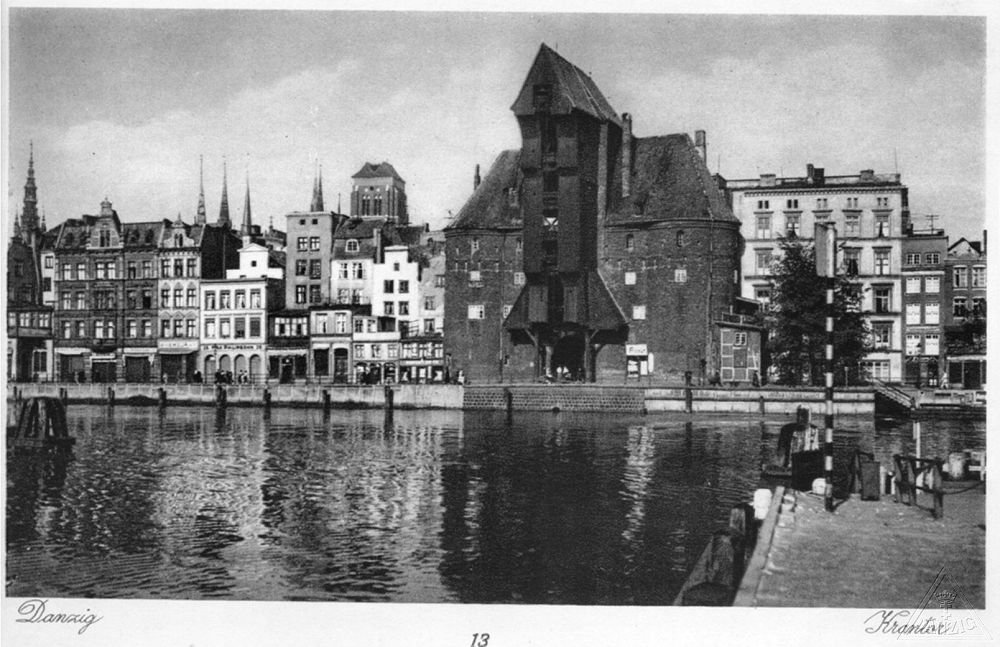

Danzig, September the 1st, 1939

Andreas Stora stirred in his sleep. In his dream, he was visiting a Greek temple with his wife Sylvia. It felt odd, for even in his current state of unconsciousness Stora was vaguely certain Sylvia had only been a fling, and that he had married his childhood friend Juliette instead. As for Greece, he could not remember if he had ever been there. Wasn’t that mission given to that prick Giroud, who claimed he knew Venizelos from before the war? Or was it that bald Swede, who kept chewing on his cigarette holder and boasted on his affairs? Stora could not remember, and next to him Sylvia kept babbling about a massive anvil that stood in the middle of the temple, claiming it was the one Vulcan himself had used to forge the sword of Leonidas. Stora was trying to tell her she had it all wrong, that Vulcan wasn’t a Greek God at all, but Sylvia kept running her mouth and the more she talked the less Stora could remember who the League had sent to Athens in his place. He was starting to feel real uneasy now, as he was certain he was forgetting something very important, that something very grave was happening right now and if he could only find out what it was maybe he could stop the world from going mad. To make things worse, there was a loud noise rising from the depths of the temple now, a loud, irregular pulsation that Sylvia kept saying was the proof Vulcan had started working on another sword on his divine anvil and why couldn’t she remember he had not married her after all and why couldn’t the Greek Gods stop making such a racket and now the Gods were angry and held him onto the anvil and Vulcan swung his hammer at Stora’s head and -

“Goddamnff!” moaned Stora, as he crashed nose first on the floor. The sudden explosion of pain brought tears to his eyes, washing away the blurry visions of the Greek temple. Around him, he could see his familiar bedroom, with its austere bed and cheap desk that made him think of his old boarding school. Wiping his face with his hand, he scooped up sweat and blood – no doubt about it, he had fallen out of his bed. Oddly enough, Stora’s ears seemed to have remained in his dream: he could still hear the irregular rumble, preceded by some kind of wheezing howl. Even more disturbingly, the ground seemed to shake slightly at intervals. Squinting at the small travel clock from the night stand, he noticed it was a quarter to five. Some dream it had been, all right.

Had Stora not been born Swiss, had his parents lived a little more to the west, or to the north, he would have recognized immediately the origin of the ruckus. But Andreas Stora had been born in the peaceful canton of Vaud just thirty-one years before, and had spent most of his younger years in small villages, among placid, hard-working people. The combined hazard of dates and geography had thus spared him the horror of celebrating his twentieth birthday in some God-forsaken muddy trench, his guts liquefying at the terrifying sound of heavy artillery fire incoming. His first reaction was therefore to go to the window, and have a look outside. But before he even reached the window, Stora froze.

Located just above the League of Nations’ Danzig Bureau, Stora’s third-floor room had a perfect view on the harbour. For the past few days, he and his colleagues had taken turn at the small window to admire and take picture of the old German battleship that had arrived on August the 28th, at the invitation of the Senate of the Free City of Danzig. The Schleswig-Holstein had been greeted by a military clique, its shiny copper instruments gleaming in the sun, and a multitude of German-speaking Danzigers that had loudly cheered the mooring operations, throwing bouquets of flowers and displaying, Stora had noticed, quite a few Nazi flags. On the following days, Stora had met small groups of German seamen in neighbouring shops and pubs, and had even, on one occasion, guided three naval officers through the old city’s maze of narrow streets to a restaurant they wanted to try. Back then, the old-looking battleship had looked friendly enough. But not now.

At some point during the night, the Schleswig-Holstein had left its mooring and steamed a little to the north of the harbour, halfway to the Westerplatte peninsula that shielded the Danzig harbour from the rigours of the Baltic. Even at this distance, there was no mistaking the German battleship for any other ship: its silhouette contrasted starkly from the fires that were raging on the Westerplatte. And every few seconds, a sudden light erupted from starboard, outlining the warship so neatly it looked like an artist’s etching. From what Stora could see, the dreadnought’s main guns were firing volley after volley upon the Polish base on the Westerplatte, and whenever the turrets fell silent for reloading, lighter guns raked the fortifications. Erupting just behind the warship, a sudden geyser startled Stora. Not only some of the Polish garrison seemed to have survived the deluge of fire, but they seemed determined to inflict some punishment of their own on the German sailors. For a minute or so, Stora stood at the window, mesmerized, as the lone Polish gun kept firing at the armoured warship.

Another broadside from the Schleswig-Holstein made the window pane tremble, and Stora shook himself into action. There were contingency plans for such situations. The first priority was to gather the League’s Free City personnel, which at the moment was scattered around the city – Stora, as High Commissioner Burckhardt’s personal secretary, was the only one to sleep in the League building. Then, they would have to find a way to get in touch with the League central offices which would give them their marching orders. Grabbing his jacket, Stora stopped at the door and casting a last glance at the window.

A few thousand feet away, Europe was descending into carnage again.

The outside perimeter of the Westerplatte fortress, September the 1st, 1939

As he thrust himself on the ground, Obergefreiter Thomas Baum wished fiery death upon his dumbass officers, their dumbass officers, and the Reichsdumbass in Chief, Adolf fucking Hitler. Upon embarking at Bremerhaven, the two naval infantry companies had been gathered before Field-Marshall von Bock, who would direct the offensive against northern Poland as Army Group A’s commanding officer. ‘You will swiftly chase the Poles from the Westerplatte, von Bock had said. You will out-number them, you will out-gun them, and you will retake in one swift blow what was once ours’. This would be a picnic, the bigwigs had told them, this will be a Blumenkrieg, this will be Prague all over again. As for the Danziger Nazis, whose useless ‘Heimwehr battalion’ was supposed to support the naval infantry assault, they had spewed the same bullshit : one shot and the Polish untermenschen would flee or surrender.

Fuck them, thought Baum. Fuck the lot of them. Half his company laid dead in the street, shredded to pieces by Polish mortars and even artillery. Nobody had told them there would be artillery. And, obviously, nobody had told the Poles they were supposed to roll over and die at the sight of the first Kriegsmarine helmet. As for those stupid Danzigers, well – fuck them too. They had assured the Lieutenant there were no more than seventy Polish soldiers stationed in the Westerplatte – a claim Lieutenant Henningsen could hardly rebuke now, not with half his head shot away by a Polish sniper as he led the first squads across the road bridge. Henningsen had been hit just as the first column of naval infantry approached the Polish base. His body had not even touched the ground, that two Polish Hotchkiss machine-guns had riddled the street with bullets, wreaking havoc in the company’s ranks. Soon a sickening mix of blood, shit and cordite had overcome Baum’s senses.

“Blumenkrieg my shiny Hessian ass” mumbled the Obergefreiter through chattering teeth, as he huddled against a half-demolished wall. His Mauser firmly held in his hands, Baum scanned the dark mass of the Westerplatte. In his mind, mindless rage was trying to get the best of abject fear. He barely noticed the ground shaking, as another broadside from the Shleswig-Holstein pummelled the Polish fortress.

London, The House of Commons, September the 3rd, 1939

Ashen-faced, the Prime Minister slowly rose from the bench and turned slowly to face both sides of Parliament, wondering if he would capture a fleeting sneer or a trace of smugness on the faces of the men assembled there that morning. But there was none – the Chief Whips, apparently, had seen to it that today’s session would be devoid of any jeers or snide remarks. From the haughtiest front-bencher to the humblest janitor, there wasn’t a single man on the House of Commons who did not feel the hour was exceptionally grave. The atmosphere was all the more subdued that earlier in the morning a team of BBC technicians had installed two large, boxy contraptions which would record and broadcast the Prime Minister’s statement and the following debates. The only noises, as Chamberlain rose, were hushed gasps of surprise at his physical appearance: gone was the almost youthful energy ‘Good ol’ Neville’ had shown after Münich, and gone was the absolute confidence the Prime Minister had so often displayed in his four years in power. Something in the elderly statesman seemed to have broken, and whether it was by the cancer that was eating him alive or by the events of the past three days was anyone’s guess.

“I have grave news” began the Prime Minister. “This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin, and his colleague in Bratislava handed the German and Slovakian Governments a final note stating that unless we heard from them by eleven o'clock, that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland a state of war would exist between our nations.”

On many a bench, Members of Parliament paled. In spite of the bleak news of the past few days – Nazi troops had taken Gdynia, and Warsaw had been firebombed by the German air force – some of them had kept alive some glimmer of hope. It was, as Churchill noted, the “Münich syndrome”. Hadn’t everything seemed lost during the Sudeten crisis as well, some of the MPs asked. Hadn’t the British government nonetheless managed to defuse the crisis? The day before, there had been appeals to President Landon emanating from several capitals, urging America to weigh in on the issue. Maybe that would make the Nazis think twice? Maybe the Prime Minister would be able to find diplomatic middle-ground, like he had so unexpectedly done at Münich? Churchill harboured no such illusions. Today’s crisis, he thought, had not happened despite of the Münich agreements, but on the contrary, because of them.

“It is now half past noon. It is my duty to tell this House no such undertaking has been received - and that none will. Consequently, this country is at – at war with both Germany and Slovakia”

As the room grew even quieter, the slight hesitation in Chamberlain’s speech had not gone unnoticed. He had pronounced “war” with tangible distaste, disgust almost, as if the word itself was poisonous. Even for the Prime Minister’s adversaries, there was something cruel that such a man, who in his old age had spent so much energy to save European peace at the risk of losing his reputation, would have to come before Parliament and acknowledged it all had been in vain.

With a heavy heart but a clear conscience, Neville Chamberlain declares war

“You can imagine what a bitter blow it is to me” continued Chamberlain. “My long struggle to win peace has failed, and yet I cannot believe that there is anything more, or anything different, that I could have done and that would have more successful.”

The whips shot warning glances across the rows of benches: now was a time for unity.

“If this had been a simple territorial dispute, then until the very last, it would have been possible to appeal to reason and arrange a peaceful and honourable settlement between Germany and Poland. But evidently Hitler had made up his mind about attacking his neighbour regardless of what happened. He now claims to have made reasonable proposals. He blames the Polish government for rejecting them, and the Western governments to have encouraged Polish intransigence. Nothing could be further from the truth. Such proposals were never shown to the Poles, or to the French, or to us. Hitler broadcast them two days ago, at the same time he ordered the German army, and his Slovakian allies, to cross the Polish border. Let it be said that Hitler’s actions show, beyond any doubt, that there is no chance of expecting this man will ever renounce his practice to use force to gain his will. Let it be said he will only be stopped by force.”

The silence, troubled only by the whirring sound of the BBC recorders, was palpable.

“Yes, our long struggle to win peace has failed, and so begins another long struggle, this time to win war. We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who as I speak is bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack on her people. This government has a clear conscience. Britain has done all that any country could do to maintain and establish peace, and more. Should Britain tolerate a situation where the security of any people or country could feel safe because of a German ruler whose word can not be trusted? No. And now that we have resolved to end this situation, I know that every Briton will play his part, with calmness and courage.”

Across the benches, MPs fidgeted, straightening up and turning around to trade looks with their neighbours.

“At such a moment, the assurance of support that we have received from the Empire, and from many friendly nations around the world are a source of profound encouragement to us. We will not fight alone for this just cause. This government has made plans under which it will be possible to carry on the work of the nation in the days of stress and strain that may be ahead. These plans – which will be discussed here and benefit from your expertise – will allow us to organize production, mobilization, transportation, shipping and civil defence in our troubled times. Now may God bless you all, and may He defend the right. Let us not forget what we shall be fighting against : not against a rival power as we used to in wars of old, but against evil forces of injustice, oppression, and persecution. Against such forces, we must prevail. Against such forces, I know we will.”

Berlin, the Foreign Ministry, September the 3rd, 1939

“This way, your Excellency” said the uniformed aide as Robert Coulondre was ushered into the vestibule. « The Reichsminister will see you right away »

As he entered Ribbentrop’s office, Coulondre was struck, as he always was, by its gigantic proportions. It seemed as large as a whole floor of the French embassy. Was it a German thing, he wondered ? Some deeply-ingrained need within the Teutonic soul ? Or was it simply a Nazi obsession with grandstanding, to the point of mistaking size for grandeur ? Looking at the letter he was holding in his left hand, Coulondre realized that was mystery he would never have enough time to solve.

« Monsieur l’Ambassadeur » said Ribbentrop, bowing slightly as he invited Coulondre to sit down. The lanky Reichsminister’s attitude was a mix of cold formality and eagerness. « Do you bring us good news from Paris ? Can we count on France to help us preserve European peace ? »

« Monsieur le Ministre du Reich » replied Coulondre, « I have come hoping to receive an answer to the letter my government has sent to the Chancellor yesterday. Should a satisfactory answer be given to our proposition for an immediate cease-fire, and the rapid evacuation of any occupied Polish and League territory, then I can assure you France will spare no effort in the interest of peace. Do you have an answer to communicate to my government? »

« I am not in a position to give you an answer » snapped Ribbentrop. «Nor can I say if there will be an answer to your government’s letter. The Führer considers a return to the statu quo ante has been rendered impossible by the British intransigence. The Reich cannot and will not bow down to ultimatums. If European peace is to be maintained, the Führer has resolved it will need to be built upon a durable solution to the Reich’s vital need for space and security. »

« I – see. » said Coulondre. « In this case - »

« If the French government », interrupted Ribbentrop, « feels compelled by its past commitments towards Poland to enter the conflict, I can only deeply regret it. The Führer harbours no ill will towards France. It is only if France attacks us that we will wage war against your country – and this will be to defend ourselves against a French aggression »

« Can I conclude from this that the German government does not intend to withdraw its forces from Poland ? » said Coulondre.

« You can » said Ribbentrop, standing up to stare at Coulondre.

« Then » said Coulondre, standing up as well « I must insist one last time upon the grave acts by the Reich’s government, which has ordered German forces to invade Poland and seize the Free City of Danzig without even a declaration of war, and which has chosen to ignore the calls by the French and British governments for an immediate ceasefire and complete withdrawal of the German army from the territories it occupies. »

Ribbentrop had crossed his arms, in an air of defiance, as if he dared Coulondre to say anything further.

« Herr Ribbentrop », said Coulondre extending the letter he had kept in his hand, « it is my duty to inform you that the French government will fulfil its obligations towards Poland, obligations that are well known by the German government »

Ribbentrop stood motionless, making no effort to take Coulondre’s letter. Finally, the Frenchman put it on the marbled desk.

« France will go down as the aggressor in this war » hissed Ribbentrop.

« Let History be the judge of that » said Coulondre. Tired by the theatrics, he turned his back on the German Minister and walking towards the large double doors. Ribbentrop leaned on his desk, his eyes on the sealed enveloppe as the Frenchman left. Despite the size of the room, he felt oppressed and short of breath.

Specht flight, over Alsace, September the 6th, 1939

As Hans turned the Henschel south-west, Hauptgefreiter Kammel lost sight of the Zerstörer fighters that played guardian angels for the four observation planes. The twin-engined Messerchmidts had joined them above Sarrebrück, describing lazy circles around the Aufklärungsgruppe 13’s Henschels – callsigns Specht One to Specht Four - as they entered French airspace. So far the flight had been uneventful, the Henschels staying above a thick bank of white clouds as they ventured into enemy territory. But that, as Kammel knew, would not last long. Flight sixteen’s mission was to provide close aerial photography of the French Army’s build-up near Saint-Avold. Army intelligence had signalled a spike in railway traffic, with heavy-duty craned being assembled in the area. As Major Lange had told the Aufklärung’s crews at the mission briefing, such movements of troops and matériel could indicate a coming offensive somewhere along the Westwall defensive line. With most of the Wehrmacht either deployed in Poland or being ferried there it was absolutely crucial to provide Army Group C with hard intelligence, to determine French intentions.

“Last check-up?” asked Hans. As always, the throat microphone garbled the voice of Specht-Two’s pilot into cartoon character’s.

For the second time since they had taken off, Kammel checked the light MG machine-gun that occupied the end of the plate’s oblong observer compartment. Taking aim at a puffy cloud that drifted slowly to the Henschel’s left, he let go a few rounds, careful not to waste any ammunition. Satisfied the weapon had neither jammed nor frozen up, he turned his attention to the Zeiss camera that was the real tool of his trade. With its large protruding objective and its C-shaped handles on either side, the Zeiss evoked a deep diver’s helmet – and once loaded with film it certainly weighed as much. Solidly fixed to a rod that ran on the side of the plane, the Zeiss could be swivelled around by the observer, much like the machine-gun, or set at a fixed angle. Three white lines, painted on the side of the fuselage, indicated the required angle at several altitudes. Not that Kammel needed such guidelines. He had been an avid photographer since his Gymnasium years, and was widely regarded as the best camera operator of the Aufklärungsgruppe.

Well above the two pairs of Henschels, the heavy Messerchmidts fighters were now almost out of sight, starting yet another slow turn as they circled around Specht Flight. The observation planes seemed lost in the cerulean infinity. Kammel waved at his Specht-One counterpart, wishing the escort fighters would be enough to keep any enemy interceptor at bay. Should their little crate fly into a roving patrol of Dewoitines or Hurricanes, Kammel knew, there would be little Hans or he could do. The Henschel was a fine machine, praised by its crews for its agility, and its supposed ability to withstand enemy fire and remain airborne. But even if that last part was true – a fact Kammel was in no hurry to check out – the observation plane was too slow to escape an Allied fighter, and too lightly-armed to scare one away. One well-adjusted burst, the Hauptgefreiter knew, and they would be goners. Half-consciously, Kammel checked the harness of his parachute.

“Alles gut! I’m set for fifteen hundred feet” he said, gluing his face to the Zeiss’ extended visor. Down below, woods and fields sailed past, cut in neat little patches by narrow roads and dirt paths.

As the Henschel dropped to its mission altitude, it passed the village of Carling, and Kammel shot a series of pictures of the main square. Instead of rows of sandbags, as could be expected if the building had still be in use, the Town Hall’s façade was blinded by planks. That was a clear sign the French authorities had evacuated the village in prevision of either combat or bombardment. That sent a small shiver up Kammel’s spine: every man they’d fly over would be an enemy soldier now. To the left, Specht-One’s observer seemed to be sharing that apprehension, as he trained his machine-gun around. Shaking his head, Kammel blinked and focused on the landscape that was flying past through the Zeiss’ visor.

Specht flight as it enters French airspace

Two minutes after, they flew over a small hamlet – L’Hôpital, Kammel remembered – where a couple of farmhouses had been built on top of a hill. As the plane shot past the hilltop, brown-clad silhouettes ran from a barn and disappeared. Kammel grimaced, half-expecting some flak, but nothing came. Hopefully the French soldiers had been too surprised by the swift passage of the Henschels to identify them.

“Enemy soldiers!” he signalled in his microphone.

“Lots of them” replied Hans, his voice now shrill and tense. “Saint-Avold’s straight ahead!”

The pilot had brought the plane on a course than ran parallel to the Metz-Sarreguemines railway. Located halfway between the two industrial cities, the Saint-Avold rail node allowed traffic to either be redirected south-west, towards Nancy, or northeast, straight into the Reich. According to Army Group C, Major Lange had said, any unusual activity there would give a good idea of the French Grand Etat-Major’s intention.

Unusual activity? thought Kammel as the marshalling areas came into view. That station’s a real anthill!

In his visor, columns of black smoke billowed as trains maneuvered in and out of Saint-Avold. At one end of the station, two stationing freight trains were belching jets of pure white steam, while a busy diesel locomotive pulled empty flatcars out of the convoy’s way. Next to the two stopped trains, hundreds of soldiers and railway workers hastily unloaded crates, bringing them to a line of lorries that seemed ready to bring the cargo to front-line units. As could be expected, the appearance of the German planes caused a commotion on the ground, but the unloading operation nonetheless continued. Cold sweat soaked Kammel’s shirt, as the deadliest part of the mission had now begun. For the observer to produce good footage of the marshalling area down below, the pilot had to maintain a certain angle between the plane and the objective. That meant Hans would, for a short but dangerous moment, fly in a fairly predictable pattern, which only allowed slow turns towards the objective, and gradual changes of altitude, so the observer could make the necessary camera adjustments. During that interval, the Henschel and its crew would be particularly vulnerable to both flak batteries and pouncing fighter planes.

The irruption of the four Henschels had caught the attention of a flak battery, as two flowers of black powder blossomed down below, briefly obscuring Kammel’s line of sight. Lifted by the explosion, Specht-two shook and fluttered for a few seconds, before Hans managed to bring it back at the required altitude. Half a minute later, another pair of explosions resounded, somewhere behind the plane. The almost lazy rate of fire confirmed what Major Lange had told his pilots: most of the French anti-aircraft artillery was still composed of either modern, small-caliber weapons or antiquated Soixante-Quinze guns, of dubious efficacy against modern, fast planes. Still, Kammel felt relieved when Hans announced an altitude change. The little plane rose rapidly, turning towards the border. To the west, Specht-One was climbing as well. A few hundred meters behind, the second pair of Henschels had begun their own reconnaissance run.

“See our escort?” asked Hans as Specht-Two emerged from a bank of clouds.

“Err...” said Kammel, looking around. To the east, two dark spots indicated rapidly approaching planes. He squinted. “Yeah, I think so. They’re coming right at us. Wait...the noses don’t look ri-”

The two Blochs shot through the clouds, passing between the two pairs of Henschels, almost stopping Kammel’s heart. Ignoring Hans’ anxious questions, he threw himself on the other side of the fuselage, twisting in his seat as he follow the lead plane. The two planes had started a sharp turn, allowing Kammel a glimpse at the French roundel on the wavy green-brown camouflage painting that, for some reason, differed from the one used in the Luftwaffe. No wonder I mistook them for our escorts!, thought Kammel as the French planes barrelled towards Metz. When the nose canopy was hidden, the twin-engined Bloch-175 did look like the Luftwaffe’s heavy fighter. Within seconds, the French planes had plunged through the bank of clouds that drifted two hundred feet below.

A chance encounter over Saint-Avold

“What was that?” asked Hans.

“We just got passed over by pair of French Schnellbombers!” announced Kammel. “Don’t worry, they’re gone. Probably our escort’s around, trying to catch up with them.”

The Aufklärungsgruppe was no stranger to the Bloch-175. On several occasions, one had flown over the airfield, disappearing before the base’s flak crew could react, and provoking quite a few acid comments at the expense of the often haughty fighter pilots supposed to maintain air superiority over Saarland. Rumour had it the Bloch could out-race even a Me-109, reason why the French Armée de l’Air had flown them non-stop along the Westwall for the past three days. Not a shot had being fired from either French or German crews, Kammel realized. He wondered if the surprise had been mutual, or if there had been some kind of professional courtesy, from one reconnaissance crew to another. Much as he wanted to believe it had been the latter, it was probably a case of complete surprise – they could count themselves lucky there had not been a mid-air collision. Kammel shook his head and scanned the skies again. This time, the Messerschmidts were in sight, and one of them was trailing a line of white-grey smoke. Evidently, professional courtesy only went so far.

With a sigh, Kammel armed the machine-gun and started his vigil again.

Two hours later, the film taken from the four cameras was developed by the Group’s lab technicians, and put in a sealed envelope bearing the stamp “Secret”. The clerk on duty handed the enveloped to a soldier from the base’s security detachment, which placed it into the saddlebag of his BMW bike. Jumping on his motorcycle, the motorcyclist sped to the main road and turned north at the first crossroads.

Bad Münstereifel, XXIII Armeekorps headquarters, September the 6th, 1939

"Weber, dim the lights, please" said the Major, turning on the Leica projector. Helped by two soldiers from von Leeb's staff, Gehlen’s adjutant closed the windows of the conference room and pulled the drapes to create as much darkness as was possible on that sunny afternoon.

With an obedient whirr, the projector started, the heat from its powerful lamp rapidly adding to Gehlen's discomfort as he stood next to the appliance. For the past three days, a sudden heat wave had set up all over Rhineland, temperature raising fifteen degrees overnight. Within the walls of St Angela Gymnasium – the high school had been requisitioned for military use as part of the regime’s anti-Catholic campaign two years before – the heat was stifling. Already Gehlen could feel sour sweat trickling down his flanks under his heavy uniform – but whether it was because of the heat from the Leica or because of the open hostility displayed in by the general officers now facing him, he could not say.

“For the past three days”, he began as pictures were shown, “the Luftwaffe has flown reconnaissance missions over the French borders, with a particularly emphasis around Metz and Strasbourg. These two cities, as you well know, house the headquarters for the French Army Groups Est and Nord-Est, which will be at the heart of any operations led against us by the French Army, either alone or in conjunction with British forces”

There were a few derisive chuckles in the audience, which Gehlen did his best to ignore.

“Operating at very high altitude, well above the ceiling of the Western Allies’ interceptors, the Luftwaffe’s Junkers-86s have been able to take extensive pictures of the French positions. That photographic evidence has been checked against radio traffic interceptions and reports from our front-line units. That has allowed our experts at Fremde Armee West to paint a clear picture of the composition of the French forces facing us.”

At the mention of “Fremde Armee West experts”, there was some derisive murmurs, and this time Gehlen had to force his voice before he could continue. Most of the officers present, Gehlen knew, had not forgiven his role in the planning conference, at Zossen, when he had allowed Warlimont and the OKW to gain the upper hand over the old Oberkommando der Heer staff. Worse, none of the men staring at him now had forgotten his forceful reassurance to General Halder that neither France nor England would take the risk to declare war on Germany over the Poland issue.

“Tell me, Major”, asked Stülpnagel, Armeekorps XXIII’s Chief of staff, “are there the same experts who told us the Western powers would not declare war and all would be quiet in the West? Those experts?”. That elicited bitter laughter around the table, as Gehlen blanched before the insult.

“Maybe the FAW could advise the enemy next time” sighed another general. “To level the playing field”.

“Ruhe, Junge” said General von Leeb, tapping on the table to bring back order. As Commander-in-Chief of Army Group C, and as such responsible for all operations along the French and Austrian borders, he had good reason to resent the consequences of the OKW’s stupid decisions, which Gehlen had enabled. But his most immediate concern was to ensure the inviolability of a thirteen hundred kilometres border that stretched from Aachen to Passau, with thirty-two divisions. Grudges, von Leeb thought, could wait.

“What are the forces arrayed against us, then, Major Gehlen?” he asked in the returned silence.

“We presently estimate those forces at thirty A-quality divisions, with more B-quality units getting formed as the French mobilization process continues. Fortunately for us, that process is not very efficient, and suffers from the lack of trained reserves.”

“Despite their Spanish experience?” asked Friedrich von Tippelskirch, whose 64th Infantry division was deployed in Saar.

“As it happens” said Gehlen, “the French have not disseminated their war-experienced officers in greener units, keeping them posted on the units that went into Spain. On the plus side, that slows down their mobilization somewhat, and lowers the general quality of their units. On the downside...”

The French front as reconstructed by German military intelligence

“Don’t tell me” said Tippelskirch. “On the downside, their ‘Spaniards’ will be a much harder proposition, should they attack us.”

“Yes” said Gehlen with growing nervousness. “And I have to tell you – they will attack us, very soon. There cannot be any doubt now.”

In the brouhaha that followed, General Erich Brandenberger, the commanding officer of Armeekorps XXIII rose.

“Is that certain?” he asked. “I mean, are you certain – really certain this time, Major?”

“All signs point to it” said Gehlen, recognizing the veiled jab for what it was. “I’ve told you the French now align thirty divisions along our border. Radio interceptions have allowed us to determine almost a third of them are what they call Divisions Cuirassées – Panzerdivisionen, Herr General. And most of their Panzer troops are Spain veterans. There has also been a flurry of activity in airbases around Metz, Mulhouse and Strasbourg. Our agents in France say their Armée de l’Air has redeployed several medium bomber squadrons. Finally, all units signal air incursions over their positions. Even taking into account they’ll need to keep several divisions on defensive positions along the Maginot Line, we can count on a thirty-plus divisions offensive against the Westwall within the next three weeks. And that is a conservative estimate. For obvious reasons, the French army’s depots and mobilization centers are very close to the German border, which means that as soon as their B-quality divisions will deploy in the Maginot fortification, they’ll be able to attack on very short notice.”

“Does the OKW know of that situation?” asked von Leeb.

“My report has been sent this very morning” said Gehlen. “I have a copy here should any of you wish to...” Check, he didn’t say, but the generals understood. “I have recommended an end to the ongoing transfer of Army Group C’s reserves to Poland, particularly of our mechanized regiments”

This time, the murmurs around the table were of approval. Army Group C’s situation was critical: of the thirty-two divisions available, only twenty covered the Franco-Belgian borders, the rest being tasked with defending Bavaria and conducting operations in Austria. And only a fraction of these twenty units could be considered mobile : AK XXIII could count on two Panzer divisions – one of which was in the middle of re-equipping its regiments with Czech tanks – and two motorized infantry divisions. The rest were solid, but slow, infantry divisions. That put von Leeb in an impossible position: he didn’t have enough units to either seize the initiative or repulse the initial attack ; worse, even if he could assemble a mobile reserve, it might be too far from the positions the French units would attack to counter-attack them in force, and the precious Panzertruppen risked being destroyed piecemeal. Defending everywhere was not an option. He had to narrow it down to a few key sectors.

“Where does the OKW think the enemy intends to attack, Major?” asked von Leeb. “Have your, your experts, worked on that question?”

“Yes sir. We have received some… indications, Herr Generaloberst” replied Gehlen. “I do have some pictures to show you, which in the opinion of my staff could point to one sector in particular. But I must confess I find it… well, it’s circumstantial evidence at best.”

Von Leeb nodded his approval of Gehlen’s newfound caution. Not that it mattered all that much anyway. When it came to military intelligence, he preferred to focus on what was knows, and reach his own conclusions, and he intended to squeeze from Gehlen every titbit of information that might prove useful.

“Pictures, then? Good. Show us.”

« The images you are going to see », said Gehlen as Weber loaded a reel of film on the extended arm of another projector, “have been obtained by the Abwehr from a British film crew yesterday ».

« Enemy propaganda then ? » asked Stülpnagel.

“In a way” said Gehlen, as a still panel bearing a handwritten date was abruptly replaced by the footage of a train stopping at a marshalling yard. « They’re actually bits that were edited-out of a Pathé newsreel. As the British army is starting to mobilize, the Chamberlain government has encouraged news agencies to film French war preparations, be that as a show of solidarity or to give their public opinion something to watch. »

There was no sound or commentary, but a painted sign on a water tower indicated « FORB », which von Leeb knew it almost certainly meant it was the Forbach train station, barely twenty kilometres into French territory. Slightly deformed by the creases on the bed sheet, a massive tank was being unloaded from an open train car, helped by a heavy-duty crane. Around the car, railway workers in coveralls and soldiers in leather jackets and soft leather caps either hurried around or watched idly as a behemoth tank was slowly, almost delicately, brought to the ground. In the background, boxy shapes indicated half a dozen similar machines were waiting.

« These tanks are French-made Chars 2C » said Gehlen. “It is an old ‘land cruiser’ design from the last months of the Great War. The men around, in leather jackets, are French tankers from the 51ème Régiment de Chars de Combat. That is the only unit to operate those super-heavy tanks. Each 2C tank has a crew of twelve, which explains the large number of soldiers you see next to each train car. »

« Grüss Gott » whispered Tippelskirch. « I knew of these things, but seeing them… These things are big as a house. Next to it our Panzer 38s look like small toys. »

« That is correct » said Gehlen. « In terms of size, they are unmatched. They are twice as long as the Hotchkiss or D-2 tanks the French Divisions Cuirassées use. The 2C has been designed as a land cruiser : slow, extremely heavy, and well-armed. »

« What do they weigh? » asked von Leeb, noticing how slowly the crane operated.

“With the additional armour plates the French army put on them a few years ago, they reach seventy tons or so. They could actually flatten most of our light tanks by simply running over them. That isn’t likely, though, as these 2C tanks can barely catch up with a running man. Speed isn’t what they have been built for. They cannot keep running at full speed very long either, as it rapidly damages their suspension and drive. In fact, we estimate their effective range at 50, 55 kilometres.”

“What is their purpose?” asked a Luftwaffe liaison officer. On the screen, the French tankers lined up in front of one tank, while a kepi-wearing officer reviewed them, gesturing at the machines with a cavalry stick. Then the angle changed, and the crew hurriedly entered the tank through a rectangular side door as large as the one used in warehouses. Again the scene cut abruptly, and was replaced on the screen by the image of the tank in movement, with French soldiers alternatively running and crawling behind it.

The ageing Char 2C, possibly the key for deciphering French intentions

“These machines have been specifically built for overcoming entrenched troops and fortified positions. Their length allows them to cross four-meter wide trenches or canals, and to climb two-meters high obstacles. Their sheer mass makes them to crush small bunkers and light fortifications, the kind of -”

“The kind of the Westwall is still largely made of” completed von Leeb, as the screen now showed a Char 2C crossing a river with soldiers running behind it, cutting to a 2C ramming an old fort’s stone wall and turning it to rubble. “I see your point, Major Gehlen”.

“There is one last piece of information that you might think significant” said Gehlen in conclusion. “It appears the French 51st Tank Regiment’s departure for Forbach was delayed for two hours, to allow a surprise visit by the French President, François de La Roque. According to witnesses, during this visit, he impressed upon the assembled soldiers that the task they were about to accomplish would be crucial for the fate of France, and for ensuring a swift Allied victory.”

“Has this visit been confirmed?”

“By several sources, including the Belgian Military attaché. The man said the French President delivered a very emotional speech.”

Standing up, von Leeb walked to the screen, watching the monstrous tanks. The machine itself did not worry him particularly: even up-armoured, it would not survive heavy artillery fire, nor would it outrun a flight of dive bombers. The real threat was the armoured divisions massing just behind the Maginot line, ready to exploit the first breach in the Westwall. But Gehlen’s ‘circumstantial evidence’ had value. If the French used their tanks according to their doctrine, then they’d deploy the 2C in the first wave, against a weak spot in the German defences. Even if the 2C’s role was mostly to boost morale, its deployment in Forbach was still significant: it told von Leeb the target would be in the immediate proximity of Forbach. Turning away from the now-empty screen, the general walked to the large map of the Saar that hanged on the wall. Checking the scale of the map, he extended thumb and index to represent more or less the operational range of the 2C, and measured up the distances from Forbach. By this logic, there was only one objective that made sense. He thought of what he knew of the French light armoured divisions and their infantry units, and found out his hypothesis made sense.

“Tippelskirch?”

“Herr Generaloberst?”

“It’s for you, I’m afraid. I think they’re going straight for Sarrebrück, quite possibly via Überherrn and Lauterbach.”

“Just my luck” grumbled von Tippelskirch.

“Gentlemen” said von Leeb, “we must at once put the Sarrebrück sector on high alert. I want more mines, and I want our reserves positioned near Überherrn rapidly.”

Game effects

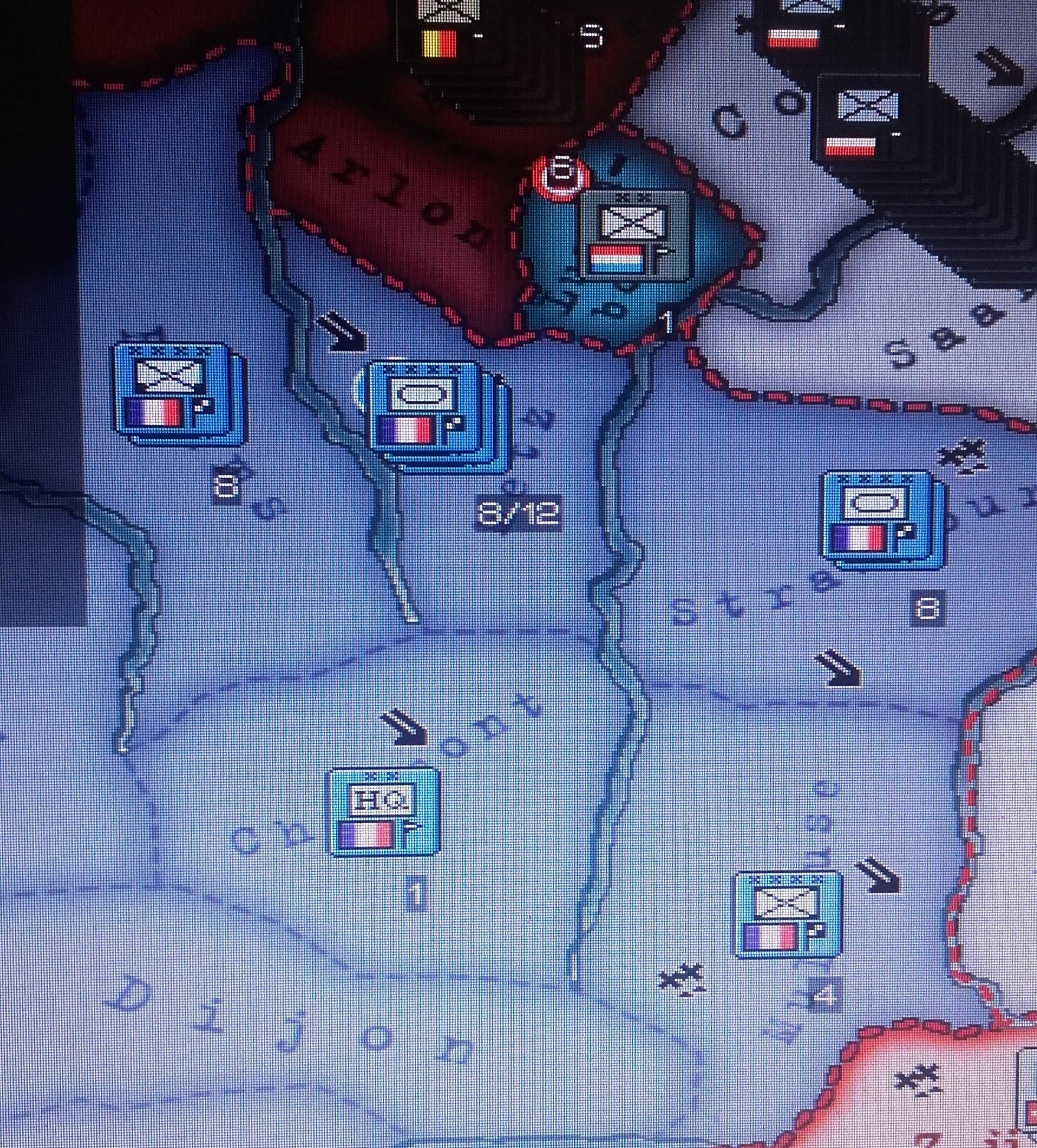

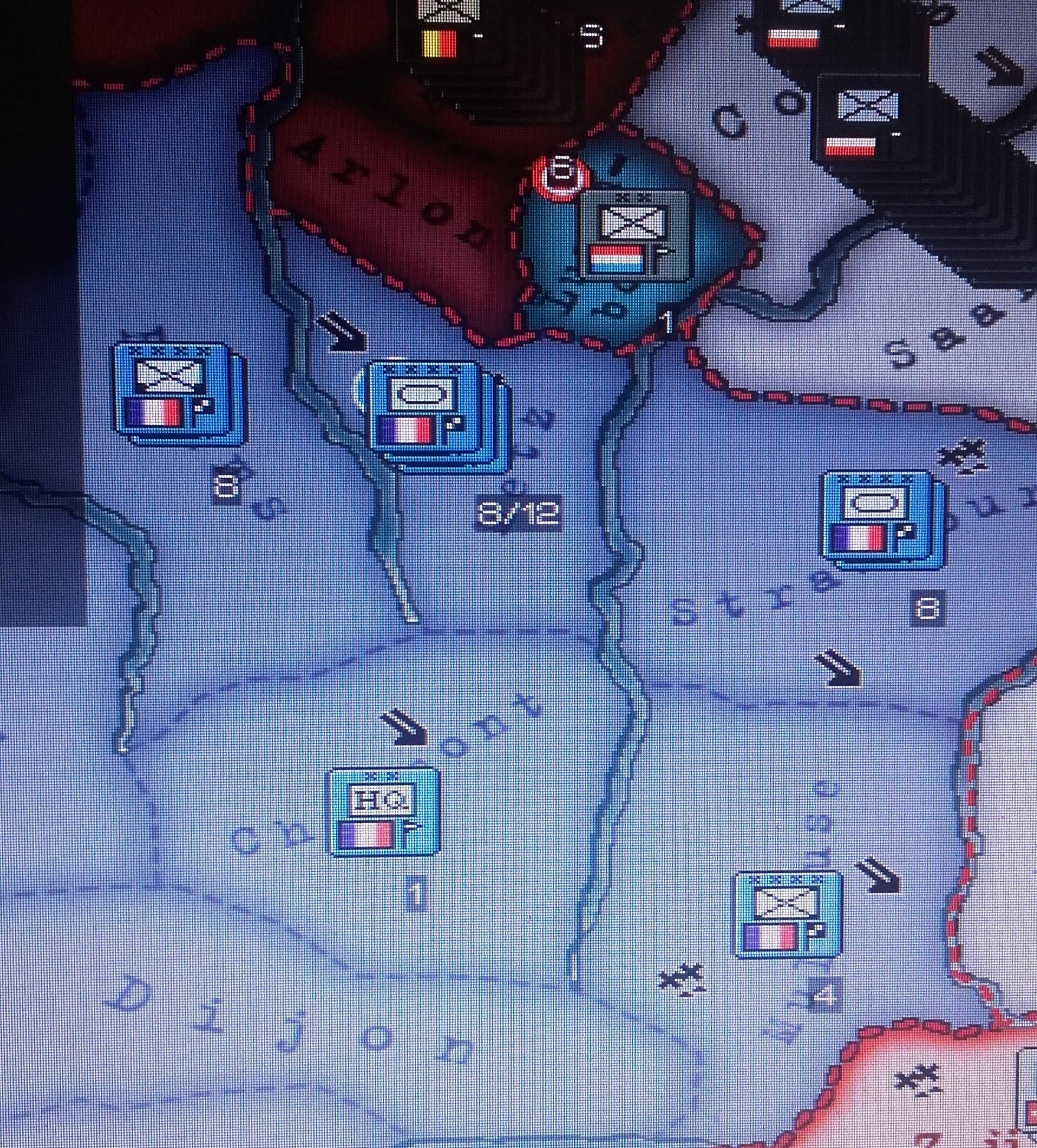

Bowing to popular demand, you have the order of battle along the Westwall on that 5th of september.

The German headquarters have a solid assessment of the French forces arrayed against them, but have gotten their orientation wrong. They expect the main attack in the Saar (as it historically happened, see below) but the my plan of operations will take a different approach. There will be an attack on the Saar alright, led by 13-15 divisions (4 of which armoured), but the main force (17 divisions, including 5 light armoured, 4 improved Cavalry, 4 motorized and 4 infantry) which is presently stationed in Strasbourg and Metz will cross Luxembourg and push north towards Cologne. I expect both Saarland and Cologne to fall rapidly, given the fact the Wehrmacht will be most busy in Poland.

My forces at the declaration of war

My plan is to establish solid defensive positions in Rhineland, which will be a serious blow to Germany’s production. I might venture into Essen if I can, to neutralize some more war industries, but I do not plan on staying there. First, I want to conduct the war in a way that fits the story, and that would be totally unrealistic (and probably as boring for you to read as it would be for me to write) to have even a beefed-up French Etat-Major suddenly turn into Patton clones. Second, I want to be able to resist the German counter-attack when the Wehrmacht turns west with a vengeance, which it will. Even with my initial advantage, let’s not forget that Germany will still out-produce, out-research and out-gun France. My next Western offensive will be when I have a far bigger army, or when my Spanish allies start ferrying troops to the front.

The War in the West is also going to be a tough one because I tweaked the alliances - a lot. And not particularly in my favour. No spoilers there, but don’t expect every minor power to gang up against Germany. Some will gang up against the Allies. Reason why I have a very small force in Marseilles ready to deploy to Italy or Austria or elsewhere if need be. North Africa is devoid of troops except one infantry division in Morocco/Algeria.

Further East, I have three infantry and one armoured divisions in Syria/Lebanon (since neither Turkey nor the Middle-East is Allied-friendly), two mountain divisions in the Horn of Africa which I intend to ferry to Saigon ASAP (should have done it earlier when I was at peace with Japan), and two more in Laos and Cambodia to fend off Siamese/Japanese offensives (and BTW Japan has now completely conquered China, which means the entire Indo-Chinese border is at risk!).

The situation in Indo-China

The entire Mediterranean Squadron (a couple of old battleships with a handful of modern cruisers and destroyers, plus 4 flotillas of submarines, are in Indochina). So far all my air power is in Metropolitan France but I want to send a couple of fighter squadrons to Saigon to protect my naval forces there. Since there can be no doubt, story-wise, that Japan will honour its alliance with the German Reich, there shall be no surprise Pearl Harbour against my units – but I still need some Tricoloured umbrella over Indochina (where my Vietnamese allies have produced several infantry divisions stationed in the coastal provinces).

Writer’s notes :

The initial attack on Poles’ Westerplatte “fortress” in Danzig was no picnic for the Germans. Not only were the Poles twice as many as the OKW thought, they put up one Hell of a fight, the Westerplatte fortress actually falling well after some Polish cities. Lieutenant Henningsen, from the Kriegsmarine naval infantry, was one of the first victims of the battle.

The words of the Franco-British declarations of war are more or less correct ( I used Chamberlain's transcript and Coulondre's notes).

The Bloch-175 was a very elegant, and indeed super-fast (for its time) reconnaissance bomber that the French Armée de l’Air used for both reconnaissance and liaison purposes. For those of you who have read it, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Flight to Arras (Pilote de Guerre, in French) is a direct testimony of his experience as a Bloch-175 pilot during the Battle of France. Feel free to imagine he’s one of the pilots crossing paths here with Kammel’s Henschel.

The Henschel 126 was a nice, versatile cantilever plane the Luftwaffe used for reconnaissance, observation and liaison purposes. It could also be used as a very light bomber, a role in which the Greek Air Force used them against Italy.

Armeekorps XXIII was responsible for the Westwall zone of operations. Its headquarters were based at Bad Münstereifel, but I have no idea where. Since there is a Catholic high school in Bad Münstereifel, and considering the Nazis’ hostility to the Catholic Church, I decided to lodge AK XXII’s headquarters in St Angela high school, but if any of you has more accurate information, I’d be curious to know.

The German officers composing the XXII AK headquarters are those commanding the German divisions facing me. These leaders gave me a headache, as HoI makes available officers who died before WW2 and some others who were too junior to command a division in 1939. I wouldn’t change a thing to the game, though, as having all those historical leaders give the game its historical flavour. So I propose you to give me some leeway here : I’ll use the names given by the game, but if for any reason the guy is dead or too young, or if I need to use the real character later in the story, let us assume some of the officers I’ll quote as commanding such-and-such unit will be their historical namesake’s younger/older brothers, or just similar-named people.

The Saar offensive feared by Army Group C is more or less the one actually planned (and partially executed) by the French Army in 1939. The whole operation would have called for 40 French divisions (with only one armoured and three mechanized) to enter the Saar, hopefully relieving the Poles. As Poland fell victim to the Blitzkrieg, the French headquarters, who had never been too eager on the whole operation to tell the truth, called back the units behind the Maginot Line. When the recall order came, several German villages and the Warndt forest had been occupied by the French Army.

Danzig, September the 1st, 1939

Andreas Stora stirred in his sleep. In his dream, he was visiting a Greek temple with his wife Sylvia. It felt odd, for even in his current state of unconsciousness Stora was vaguely certain Sylvia had only been a fling, and that he had married his childhood friend Juliette instead. As for Greece, he could not remember if he had ever been there. Wasn’t that mission given to that prick Giroud, who claimed he knew Venizelos from before the war? Or was it that bald Swede, who kept chewing on his cigarette holder and boasted on his affairs? Stora could not remember, and next to him Sylvia kept babbling about a massive anvil that stood in the middle of the temple, claiming it was the one Vulcan himself had used to forge the sword of Leonidas. Stora was trying to tell her she had it all wrong, that Vulcan wasn’t a Greek God at all, but Sylvia kept running her mouth and the more she talked the less Stora could remember who the League had sent to Athens in his place. He was starting to feel real uneasy now, as he was certain he was forgetting something very important, that something very grave was happening right now and if he could only find out what it was maybe he could stop the world from going mad. To make things worse, there was a loud noise rising from the depths of the temple now, a loud, irregular pulsation that Sylvia kept saying was the proof Vulcan had started working on another sword on his divine anvil and why couldn’t she remember he had not married her after all and why couldn’t the Greek Gods stop making such a racket and now the Gods were angry and held him onto the anvil and Vulcan swung his hammer at Stora’s head and -

“Goddamnff!” moaned Stora, as he crashed nose first on the floor. The sudden explosion of pain brought tears to his eyes, washing away the blurry visions of the Greek temple. Around him, he could see his familiar bedroom, with its austere bed and cheap desk that made him think of his old boarding school. Wiping his face with his hand, he scooped up sweat and blood – no doubt about it, he had fallen out of his bed. Oddly enough, Stora’s ears seemed to have remained in his dream: he could still hear the irregular rumble, preceded by some kind of wheezing howl. Even more disturbingly, the ground seemed to shake slightly at intervals. Squinting at the small travel clock from the night stand, he noticed it was a quarter to five. Some dream it had been, all right.

Had Stora not been born Swiss, had his parents lived a little more to the west, or to the north, he would have recognized immediately the origin of the ruckus. But Andreas Stora had been born in the peaceful canton of Vaud just thirty-one years before, and had spent most of his younger years in small villages, among placid, hard-working people. The combined hazard of dates and geography had thus spared him the horror of celebrating his twentieth birthday in some God-forsaken muddy trench, his guts liquefying at the terrifying sound of heavy artillery fire incoming. His first reaction was therefore to go to the window, and have a look outside. But before he even reached the window, Stora froze.

Located just above the League of Nations’ Danzig Bureau, Stora’s third-floor room had a perfect view on the harbour. For the past few days, he and his colleagues had taken turn at the small window to admire and take picture of the old German battleship that had arrived on August the 28th, at the invitation of the Senate of the Free City of Danzig. The Schleswig-Holstein had been greeted by a military clique, its shiny copper instruments gleaming in the sun, and a multitude of German-speaking Danzigers that had loudly cheered the mooring operations, throwing bouquets of flowers and displaying, Stora had noticed, quite a few Nazi flags. On the following days, Stora had met small groups of German seamen in neighbouring shops and pubs, and had even, on one occasion, guided three naval officers through the old city’s maze of narrow streets to a restaurant they wanted to try. Back then, the old-looking battleship had looked friendly enough. But not now.

At some point during the night, the Schleswig-Holstein had left its mooring and steamed a little to the north of the harbour, halfway to the Westerplatte peninsula that shielded the Danzig harbour from the rigours of the Baltic. Even at this distance, there was no mistaking the German battleship for any other ship: its silhouette contrasted starkly from the fires that were raging on the Westerplatte. And every few seconds, a sudden light erupted from starboard, outlining the warship so neatly it looked like an artist’s etching. From what Stora could see, the dreadnought’s main guns were firing volley after volley upon the Polish base on the Westerplatte, and whenever the turrets fell silent for reloading, lighter guns raked the fortifications. Erupting just behind the warship, a sudden geyser startled Stora. Not only some of the Polish garrison seemed to have survived the deluge of fire, but they seemed determined to inflict some punishment of their own on the German sailors. For a minute or so, Stora stood at the window, mesmerized, as the lone Polish gun kept firing at the armoured warship.

Another broadside from the Schleswig-Holstein made the window pane tremble, and Stora shook himself into action. There were contingency plans for such situations. The first priority was to gather the League’s Free City personnel, which at the moment was scattered around the city – Stora, as High Commissioner Burckhardt’s personal secretary, was the only one to sleep in the League building. Then, they would have to find a way to get in touch with the League central offices which would give them their marching orders. Grabbing his jacket, Stora stopped at the door and casting a last glance at the window.

A few thousand feet away, Europe was descending into carnage again.

The outside perimeter of the Westerplatte fortress, September the 1st, 1939

As he thrust himself on the ground, Obergefreiter Thomas Baum wished fiery death upon his dumbass officers, their dumbass officers, and the Reichsdumbass in Chief, Adolf fucking Hitler. Upon embarking at Bremerhaven, the two naval infantry companies had been gathered before Field-Marshall von Bock, who would direct the offensive against northern Poland as Army Group A’s commanding officer. ‘You will swiftly chase the Poles from the Westerplatte, von Bock had said. You will out-number them, you will out-gun them, and you will retake in one swift blow what was once ours’. This would be a picnic, the bigwigs had told them, this will be a Blumenkrieg, this will be Prague all over again. As for the Danziger Nazis, whose useless ‘Heimwehr battalion’ was supposed to support the naval infantry assault, they had spewed the same bullshit : one shot and the Polish untermenschen would flee or surrender.

Fuck them, thought Baum. Fuck the lot of them. Half his company laid dead in the street, shredded to pieces by Polish mortars and even artillery. Nobody had told them there would be artillery. And, obviously, nobody had told the Poles they were supposed to roll over and die at the sight of the first Kriegsmarine helmet. As for those stupid Danzigers, well – fuck them too. They had assured the Lieutenant there were no more than seventy Polish soldiers stationed in the Westerplatte – a claim Lieutenant Henningsen could hardly rebuke now, not with half his head shot away by a Polish sniper as he led the first squads across the road bridge. Henningsen had been hit just as the first column of naval infantry approached the Polish base. His body had not even touched the ground, that two Polish Hotchkiss machine-guns had riddled the street with bullets, wreaking havoc in the company’s ranks. Soon a sickening mix of blood, shit and cordite had overcome Baum’s senses.

“Blumenkrieg my shiny Hessian ass” mumbled the Obergefreiter through chattering teeth, as he huddled against a half-demolished wall. His Mauser firmly held in his hands, Baum scanned the dark mass of the Westerplatte. In his mind, mindless rage was trying to get the best of abject fear. He barely noticed the ground shaking, as another broadside from the Shleswig-Holstein pummelled the Polish fortress.

London, The House of Commons, September the 3rd, 1939

Ashen-faced, the Prime Minister slowly rose from the bench and turned slowly to face both sides of Parliament, wondering if he would capture a fleeting sneer or a trace of smugness on the faces of the men assembled there that morning. But there was none – the Chief Whips, apparently, had seen to it that today’s session would be devoid of any jeers or snide remarks. From the haughtiest front-bencher to the humblest janitor, there wasn’t a single man on the House of Commons who did not feel the hour was exceptionally grave. The atmosphere was all the more subdued that earlier in the morning a team of BBC technicians had installed two large, boxy contraptions which would record and broadcast the Prime Minister’s statement and the following debates. The only noises, as Chamberlain rose, were hushed gasps of surprise at his physical appearance: gone was the almost youthful energy ‘Good ol’ Neville’ had shown after Münich, and gone was the absolute confidence the Prime Minister had so often displayed in his four years in power. Something in the elderly statesman seemed to have broken, and whether it was by the cancer that was eating him alive or by the events of the past three days was anyone’s guess.

“I have grave news” began the Prime Minister. “This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin, and his colleague in Bratislava handed the German and Slovakian Governments a final note stating that unless we heard from them by eleven o'clock, that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland a state of war would exist between our nations.”

On many a bench, Members of Parliament paled. In spite of the bleak news of the past few days – Nazi troops had taken Gdynia, and Warsaw had been firebombed by the German air force – some of them had kept alive some glimmer of hope. It was, as Churchill noted, the “Münich syndrome”. Hadn’t everything seemed lost during the Sudeten crisis as well, some of the MPs asked. Hadn’t the British government nonetheless managed to defuse the crisis? The day before, there had been appeals to President Landon emanating from several capitals, urging America to weigh in on the issue. Maybe that would make the Nazis think twice? Maybe the Prime Minister would be able to find diplomatic middle-ground, like he had so unexpectedly done at Münich? Churchill harboured no such illusions. Today’s crisis, he thought, had not happened despite of the Münich agreements, but on the contrary, because of them.

“It is now half past noon. It is my duty to tell this House no such undertaking has been received - and that none will. Consequently, this country is at – at war with both Germany and Slovakia”

As the room grew even quieter, the slight hesitation in Chamberlain’s speech had not gone unnoticed. He had pronounced “war” with tangible distaste, disgust almost, as if the word itself was poisonous. Even for the Prime Minister’s adversaries, there was something cruel that such a man, who in his old age had spent so much energy to save European peace at the risk of losing his reputation, would have to come before Parliament and acknowledged it all had been in vain.

With a heavy heart but a clear conscience, Neville Chamberlain declares war

“You can imagine what a bitter blow it is to me” continued Chamberlain. “My long struggle to win peace has failed, and yet I cannot believe that there is anything more, or anything different, that I could have done and that would have more successful.”

The whips shot warning glances across the rows of benches: now was a time for unity.

“If this had been a simple territorial dispute, then until the very last, it would have been possible to appeal to reason and arrange a peaceful and honourable settlement between Germany and Poland. But evidently Hitler had made up his mind about attacking his neighbour regardless of what happened. He now claims to have made reasonable proposals. He blames the Polish government for rejecting them, and the Western governments to have encouraged Polish intransigence. Nothing could be further from the truth. Such proposals were never shown to the Poles, or to the French, or to us. Hitler broadcast them two days ago, at the same time he ordered the German army, and his Slovakian allies, to cross the Polish border. Let it be said that Hitler’s actions show, beyond any doubt, that there is no chance of expecting this man will ever renounce his practice to use force to gain his will. Let it be said he will only be stopped by force.”

The silence, troubled only by the whirring sound of the BBC recorders, was palpable.

“Yes, our long struggle to win peace has failed, and so begins another long struggle, this time to win war. We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who as I speak is bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack on her people. This government has a clear conscience. Britain has done all that any country could do to maintain and establish peace, and more. Should Britain tolerate a situation where the security of any people or country could feel safe because of a German ruler whose word can not be trusted? No. And now that we have resolved to end this situation, I know that every Briton will play his part, with calmness and courage.”

Across the benches, MPs fidgeted, straightening up and turning around to trade looks with their neighbours.

“At such a moment, the assurance of support that we have received from the Empire, and from many friendly nations around the world are a source of profound encouragement to us. We will not fight alone for this just cause. This government has made plans under which it will be possible to carry on the work of the nation in the days of stress and strain that may be ahead. These plans – which will be discussed here and benefit from your expertise – will allow us to organize production, mobilization, transportation, shipping and civil defence in our troubled times. Now may God bless you all, and may He defend the right. Let us not forget what we shall be fighting against : not against a rival power as we used to in wars of old, but against evil forces of injustice, oppression, and persecution. Against such forces, we must prevail. Against such forces, I know we will.”

Berlin, the Foreign Ministry, September the 3rd, 1939

“This way, your Excellency” said the uniformed aide as Robert Coulondre was ushered into the vestibule. « The Reichsminister will see you right away »

As he entered Ribbentrop’s office, Coulondre was struck, as he always was, by its gigantic proportions. It seemed as large as a whole floor of the French embassy. Was it a German thing, he wondered ? Some deeply-ingrained need within the Teutonic soul ? Or was it simply a Nazi obsession with grandstanding, to the point of mistaking size for grandeur ? Looking at the letter he was holding in his left hand, Coulondre realized that was mystery he would never have enough time to solve.

« Monsieur l’Ambassadeur » said Ribbentrop, bowing slightly as he invited Coulondre to sit down. The lanky Reichsminister’s attitude was a mix of cold formality and eagerness. « Do you bring us good news from Paris ? Can we count on France to help us preserve European peace ? »

« Monsieur le Ministre du Reich » replied Coulondre, « I have come hoping to receive an answer to the letter my government has sent to the Chancellor yesterday. Should a satisfactory answer be given to our proposition for an immediate cease-fire, and the rapid evacuation of any occupied Polish and League territory, then I can assure you France will spare no effort in the interest of peace. Do you have an answer to communicate to my government? »

« I am not in a position to give you an answer » snapped Ribbentrop. «Nor can I say if there will be an answer to your government’s letter. The Führer considers a return to the statu quo ante has been rendered impossible by the British intransigence. The Reich cannot and will not bow down to ultimatums. If European peace is to be maintained, the Führer has resolved it will need to be built upon a durable solution to the Reich’s vital need for space and security. »

« I – see. » said Coulondre. « In this case - »

« If the French government », interrupted Ribbentrop, « feels compelled by its past commitments towards Poland to enter the conflict, I can only deeply regret it. The Führer harbours no ill will towards France. It is only if France attacks us that we will wage war against your country – and this will be to defend ourselves against a French aggression »

Robert Coulondre, at the reception held for his nomination as France’s Ambassador to the German Reich

« Can I conclude from this that the German government does not intend to withdraw its forces from Poland ? » said Coulondre.

« You can » said Ribbentrop, standing up to stare at Coulondre.

« Then » said Coulondre, standing up as well « I must insist one last time upon the grave acts by the Reich’s government, which has ordered German forces to invade Poland and seize the Free City of Danzig without even a declaration of war, and which has chosen to ignore the calls by the French and British governments for an immediate ceasefire and complete withdrawal of the German army from the territories it occupies. »

Ribbentrop had crossed his arms, in an air of defiance, as if he dared Coulondre to say anything further.

« Herr Ribbentrop », said Coulondre extending the letter he had kept in his hand, « it is my duty to inform you that the French government will fulfil its obligations towards Poland, obligations that are well known by the German government »

Ribbentrop stood motionless, making no effort to take Coulondre’s letter. Finally, the Frenchman put it on the marbled desk.

« France will go down as the aggressor in this war » hissed Ribbentrop.

« Let History be the judge of that » said Coulondre. Tired by the theatrics, he turned his back on the German Minister and walking towards the large double doors. Ribbentrop leaned on his desk, his eyes on the sealed enveloppe as the Frenchman left. Despite the size of the room, he felt oppressed and short of breath.

Specht flight, over Alsace, September the 6th, 1939

As Hans turned the Henschel south-west, Hauptgefreiter Kammel lost sight of the Zerstörer fighters that played guardian angels for the four observation planes. The twin-engined Messerchmidts had joined them above Sarrebrück, describing lazy circles around the Aufklärungsgruppe 13’s Henschels – callsigns Specht One to Specht Four - as they entered French airspace. So far the flight had been uneventful, the Henschels staying above a thick bank of white clouds as they ventured into enemy territory. But that, as Kammel knew, would not last long. Flight sixteen’s mission was to provide close aerial photography of the French Army’s build-up near Saint-Avold. Army intelligence had signalled a spike in railway traffic, with heavy-duty craned being assembled in the area. As Major Lange had told the Aufklärung’s crews at the mission briefing, such movements of troops and matériel could indicate a coming offensive somewhere along the Westwall defensive line. With most of the Wehrmacht either deployed in Poland or being ferried there it was absolutely crucial to provide Army Group C with hard intelligence, to determine French intentions.

“Last check-up?” asked Hans. As always, the throat microphone garbled the voice of Specht-Two’s pilot into cartoon character’s.

For the second time since they had taken off, Kammel checked the light MG machine-gun that occupied the end of the plate’s oblong observer compartment. Taking aim at a puffy cloud that drifted slowly to the Henschel’s left, he let go a few rounds, careful not to waste any ammunition. Satisfied the weapon had neither jammed nor frozen up, he turned his attention to the Zeiss camera that was the real tool of his trade. With its large protruding objective and its C-shaped handles on either side, the Zeiss evoked a deep diver’s helmet – and once loaded with film it certainly weighed as much. Solidly fixed to a rod that ran on the side of the plane, the Zeiss could be swivelled around by the observer, much like the machine-gun, or set at a fixed angle. Three white lines, painted on the side of the fuselage, indicated the required angle at several altitudes. Not that Kammel needed such guidelines. He had been an avid photographer since his Gymnasium years, and was widely regarded as the best camera operator of the Aufklärungsgruppe.

Well above the two pairs of Henschels, the heavy Messerchmidts fighters were now almost out of sight, starting yet another slow turn as they circled around Specht Flight. The observation planes seemed lost in the cerulean infinity. Kammel waved at his Specht-One counterpart, wishing the escort fighters would be enough to keep any enemy interceptor at bay. Should their little crate fly into a roving patrol of Dewoitines or Hurricanes, Kammel knew, there would be little Hans or he could do. The Henschel was a fine machine, praised by its crews for its agility, and its supposed ability to withstand enemy fire and remain airborne. But even if that last part was true – a fact Kammel was in no hurry to check out – the observation plane was too slow to escape an Allied fighter, and too lightly-armed to scare one away. One well-adjusted burst, the Hauptgefreiter knew, and they would be goners. Half-consciously, Kammel checked the harness of his parachute.

“Alles gut! I’m set for fifteen hundred feet” he said, gluing his face to the Zeiss’ extended visor. Down below, woods and fields sailed past, cut in neat little patches by narrow roads and dirt paths.

As the Henschel dropped to its mission altitude, it passed the village of Carling, and Kammel shot a series of pictures of the main square. Instead of rows of sandbags, as could be expected if the building had still be in use, the Town Hall’s façade was blinded by planks. That was a clear sign the French authorities had evacuated the village in prevision of either combat or bombardment. That sent a small shiver up Kammel’s spine: every man they’d fly over would be an enemy soldier now. To the left, Specht-One’s observer seemed to be sharing that apprehension, as he trained his machine-gun around. Shaking his head, Kammel blinked and focused on the landscape that was flying past through the Zeiss’ visor.

Specht flight as it enters French airspace

Two minutes after, they flew over a small hamlet – L’Hôpital, Kammel remembered – where a couple of farmhouses had been built on top of a hill. As the plane shot past the hilltop, brown-clad silhouettes ran from a barn and disappeared. Kammel grimaced, half-expecting some flak, but nothing came. Hopefully the French soldiers had been too surprised by the swift passage of the Henschels to identify them.

“Enemy soldiers!” he signalled in his microphone.

“Lots of them” replied Hans, his voice now shrill and tense. “Saint-Avold’s straight ahead!”

The pilot had brought the plane on a course than ran parallel to the Metz-Sarreguemines railway. Located halfway between the two industrial cities, the Saint-Avold rail node allowed traffic to either be redirected south-west, towards Nancy, or northeast, straight into the Reich. According to Army Group C, Major Lange had said, any unusual activity there would give a good idea of the French Grand Etat-Major’s intention.

Unusual activity? thought Kammel as the marshalling areas came into view. That station’s a real anthill!

In his visor, columns of black smoke billowed as trains maneuvered in and out of Saint-Avold. At one end of the station, two stationing freight trains were belching jets of pure white steam, while a busy diesel locomotive pulled empty flatcars out of the convoy’s way. Next to the two stopped trains, hundreds of soldiers and railway workers hastily unloaded crates, bringing them to a line of lorries that seemed ready to bring the cargo to front-line units. As could be expected, the appearance of the German planes caused a commotion on the ground, but the unloading operation nonetheless continued. Cold sweat soaked Kammel’s shirt, as the deadliest part of the mission had now begun. For the observer to produce good footage of the marshalling area down below, the pilot had to maintain a certain angle between the plane and the objective. That meant Hans would, for a short but dangerous moment, fly in a fairly predictable pattern, which only allowed slow turns towards the objective, and gradual changes of altitude, so the observer could make the necessary camera adjustments. During that interval, the Henschel and its crew would be particularly vulnerable to both flak batteries and pouncing fighter planes.

The irruption of the four Henschels had caught the attention of a flak battery, as two flowers of black powder blossomed down below, briefly obscuring Kammel’s line of sight. Lifted by the explosion, Specht-two shook and fluttered for a few seconds, before Hans managed to bring it back at the required altitude. Half a minute later, another pair of explosions resounded, somewhere behind the plane. The almost lazy rate of fire confirmed what Major Lange had told his pilots: most of the French anti-aircraft artillery was still composed of either modern, small-caliber weapons or antiquated Soixante-Quinze guns, of dubious efficacy against modern, fast planes. Still, Kammel felt relieved when Hans announced an altitude change. The little plane rose rapidly, turning towards the border. To the west, Specht-One was climbing as well. A few hundred meters behind, the second pair of Henschels had begun their own reconnaissance run.

“See our escort?” asked Hans as Specht-Two emerged from a bank of clouds.

“Err...” said Kammel, looking around. To the east, two dark spots indicated rapidly approaching planes. He squinted. “Yeah, I think so. They’re coming right at us. Wait...the noses don’t look ri-”

The two Blochs shot through the clouds, passing between the two pairs of Henschels, almost stopping Kammel’s heart. Ignoring Hans’ anxious questions, he threw himself on the other side of the fuselage, twisting in his seat as he follow the lead plane. The two planes had started a sharp turn, allowing Kammel a glimpse at the French roundel on the wavy green-brown camouflage painting that, for some reason, differed from the one used in the Luftwaffe. No wonder I mistook them for our escorts!, thought Kammel as the French planes barrelled towards Metz. When the nose canopy was hidden, the twin-engined Bloch-175 did look like the Luftwaffe’s heavy fighter. Within seconds, the French planes had plunged through the bank of clouds that drifted two hundred feet below.

A chance encounter over Saint-Avold

“What was that?” asked Hans.

“We just got passed over by pair of French Schnellbombers!” announced Kammel. “Don’t worry, they’re gone. Probably our escort’s around, trying to catch up with them.”

The Aufklärungsgruppe was no stranger to the Bloch-175. On several occasions, one had flown over the airfield, disappearing before the base’s flak crew could react, and provoking quite a few acid comments at the expense of the often haughty fighter pilots supposed to maintain air superiority over Saarland. Rumour had it the Bloch could out-race even a Me-109, reason why the French Armée de l’Air had flown them non-stop along the Westwall for the past three days. Not a shot had being fired from either French or German crews, Kammel realized. He wondered if the surprise had been mutual, or if there had been some kind of professional courtesy, from one reconnaissance crew to another. Much as he wanted to believe it had been the latter, it was probably a case of complete surprise – they could count themselves lucky there had not been a mid-air collision. Kammel shook his head and scanned the skies again. This time, the Messerschmidts were in sight, and one of them was trailing a line of white-grey smoke. Evidently, professional courtesy only went so far.