Chapter LXXXI: A Grand Rivalry

(1 January 543/211 BC to 18 July 544/210 BC)

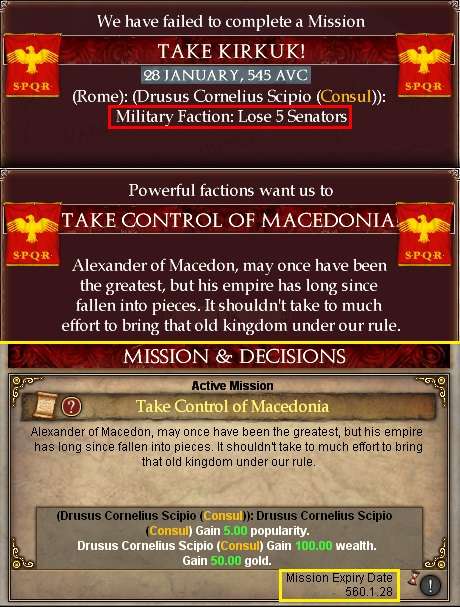

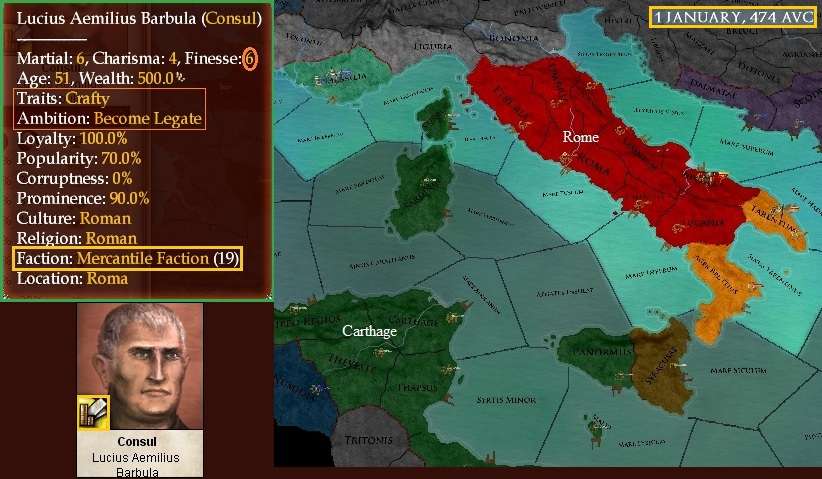

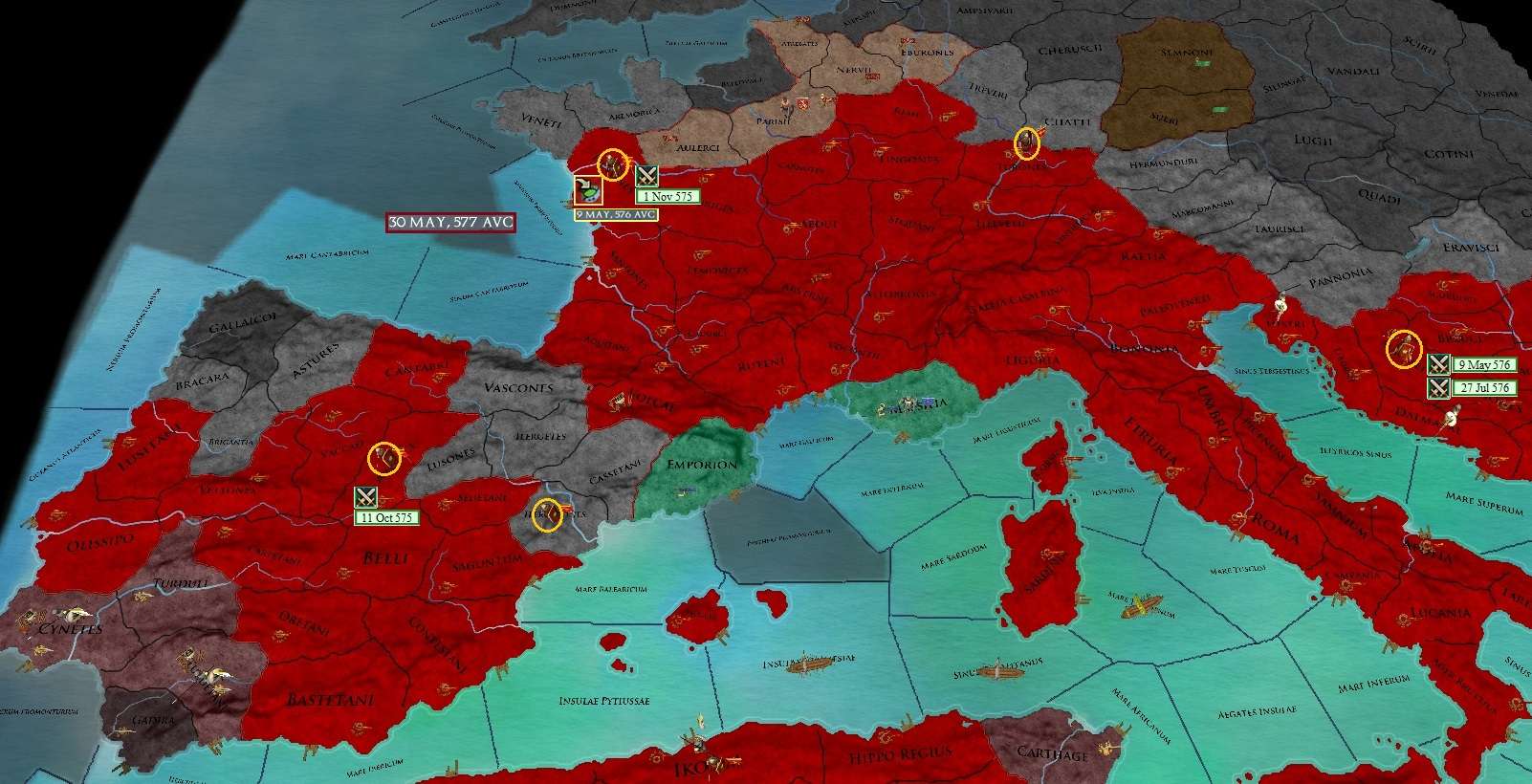

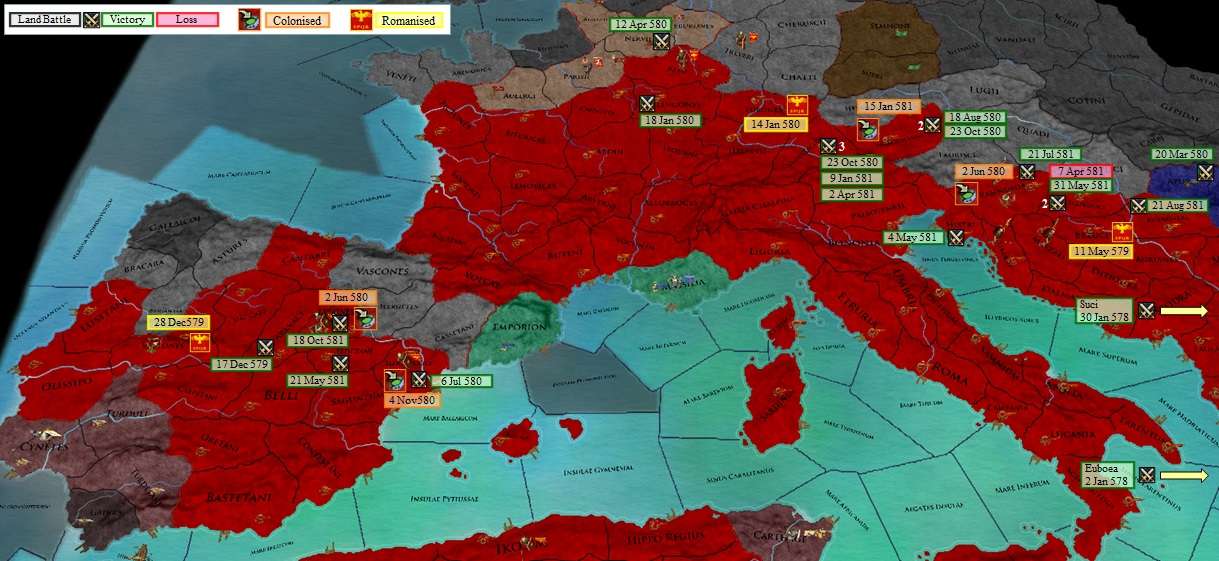

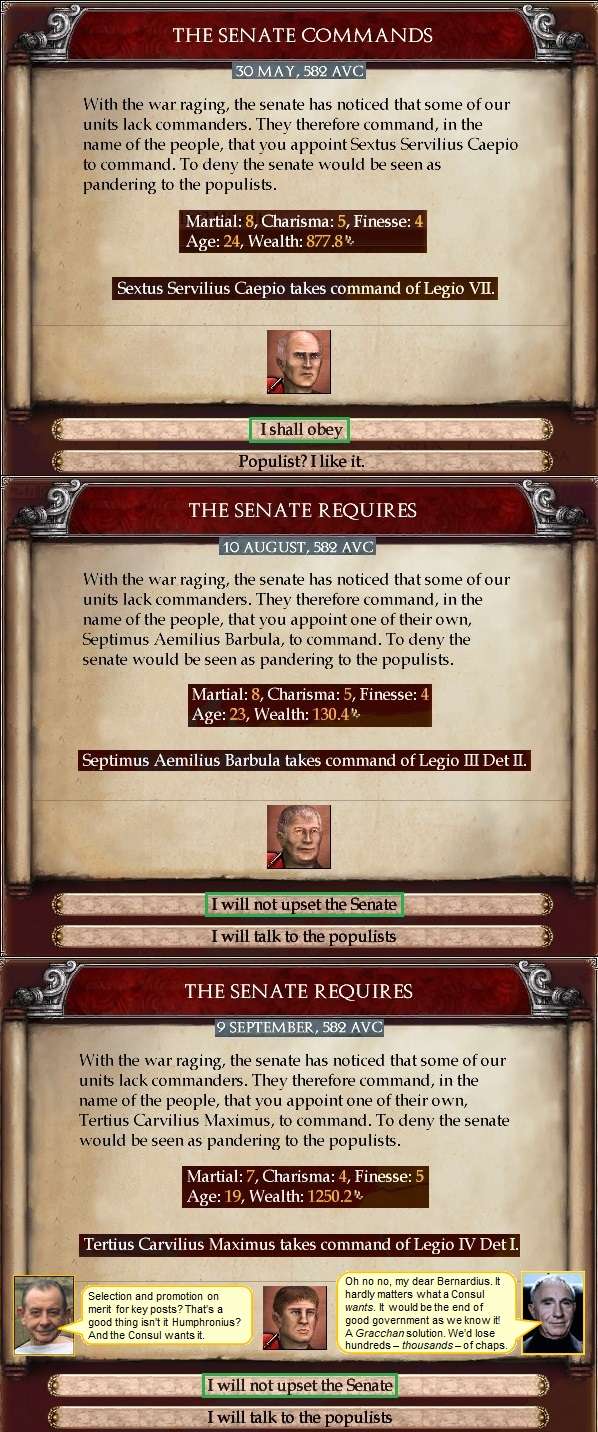

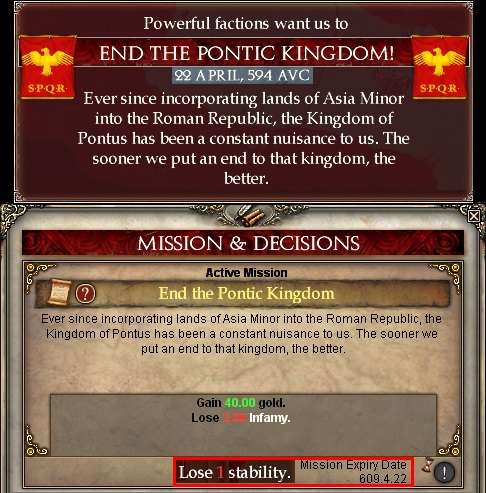

Foreword. In this episode, we will see both the next phase of the Great Eastern War – principally against Pontus – and other matters around the Republic. Macedon had been taken out of the war in a separate peace the year before, in March of 542, that ceded three Greek provinces to Rome. A white peace with the Seleucid Rebels had been concluded at the same time.(1 January 543/211 BC to 18 July 544/210 BC)

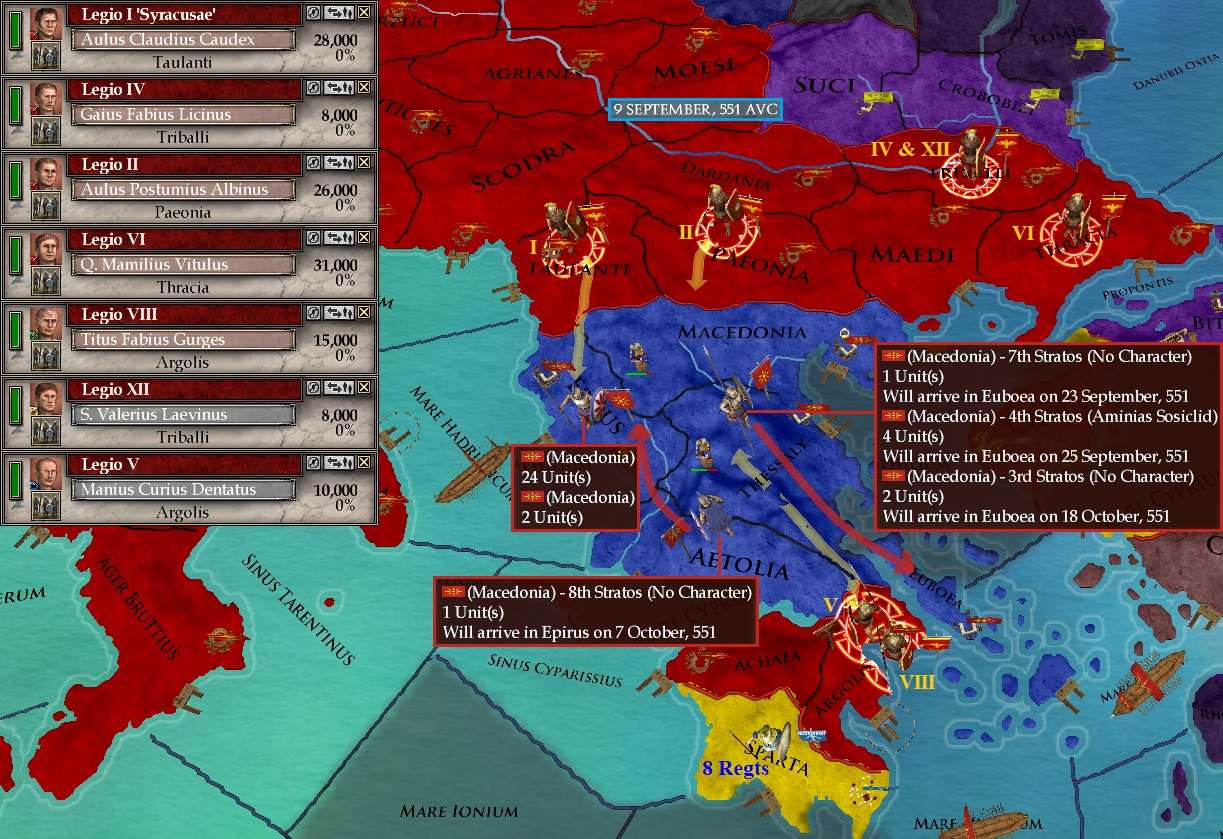

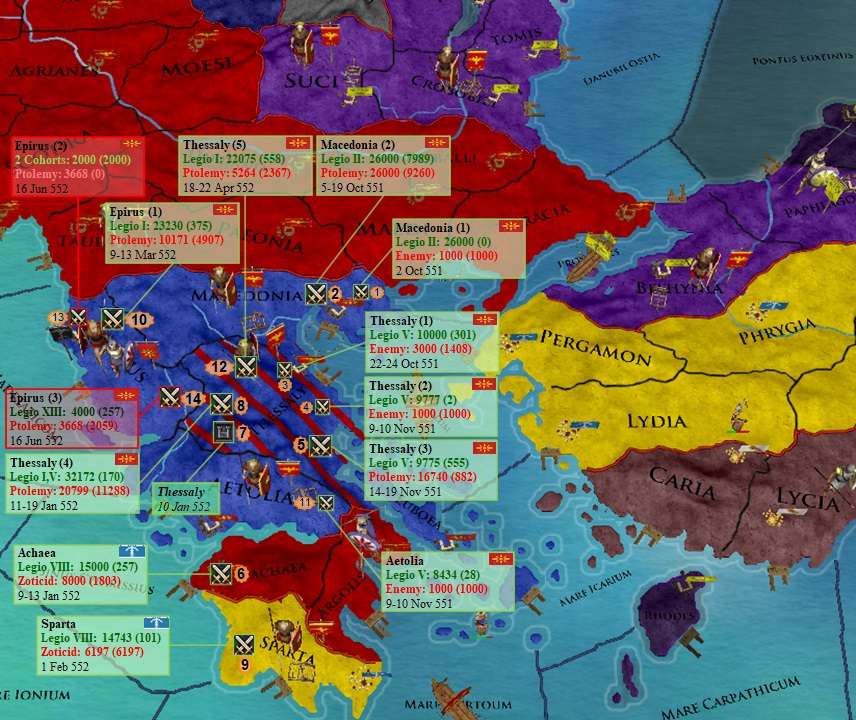

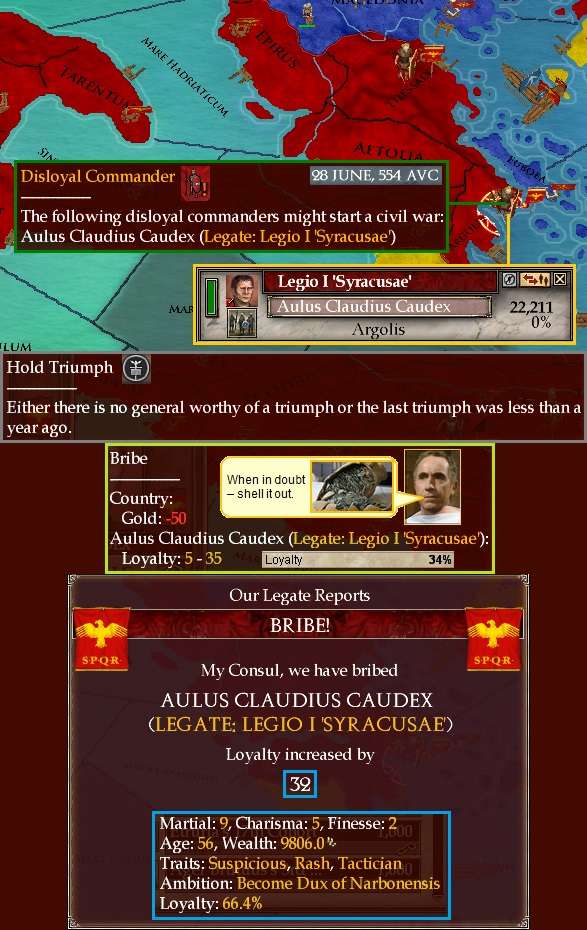

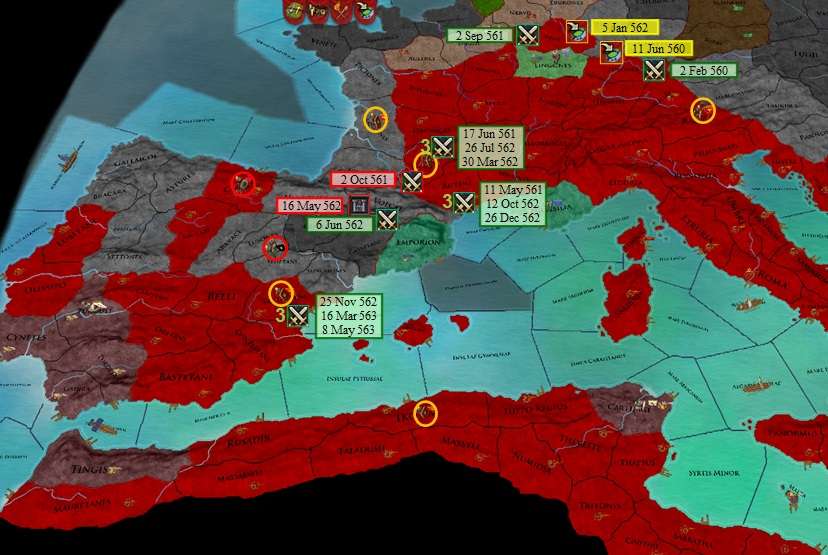

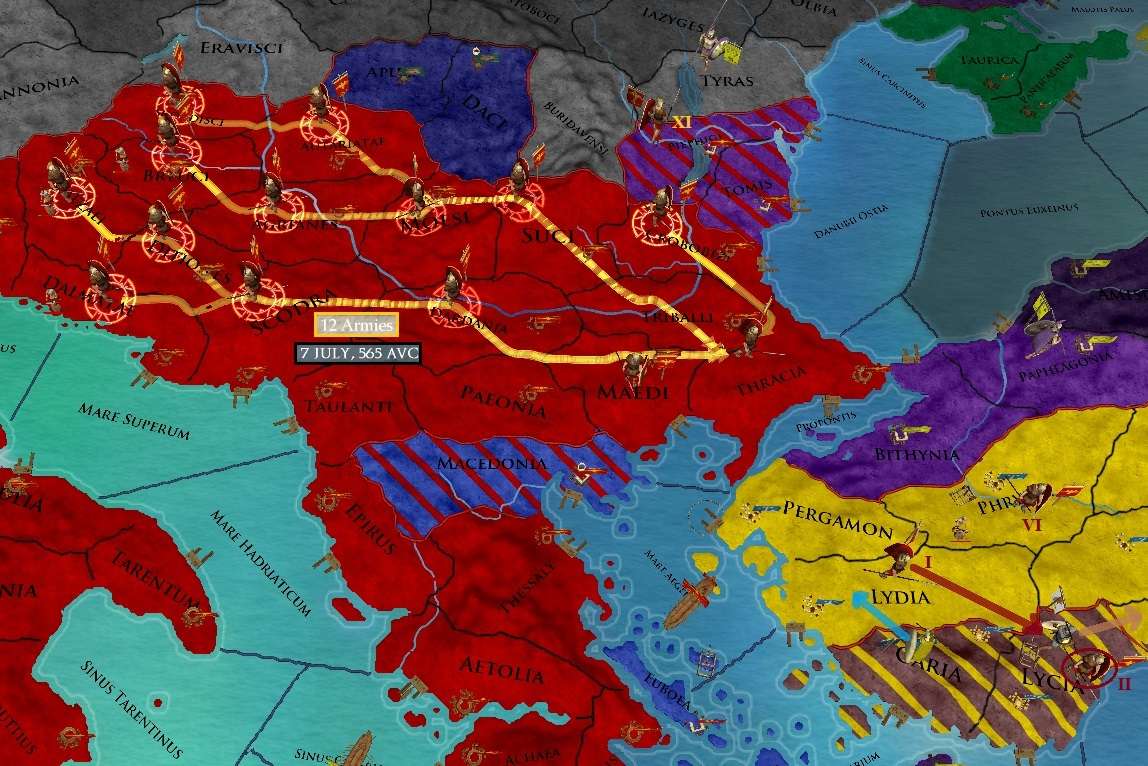

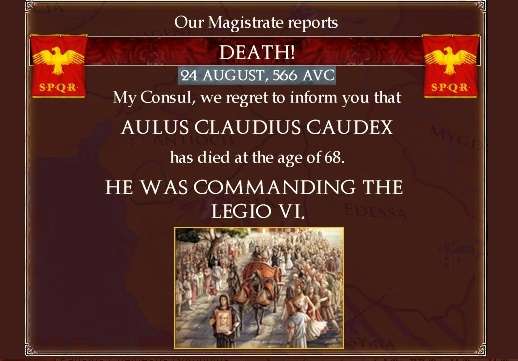

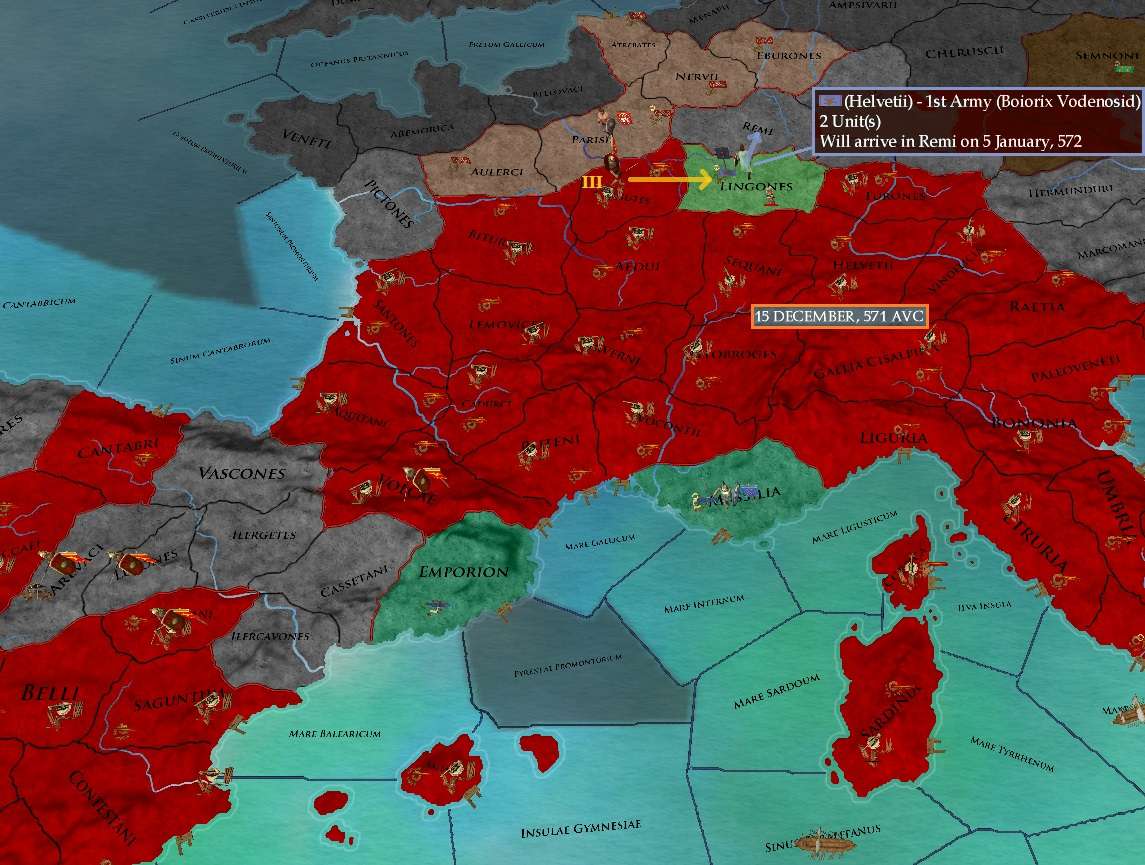

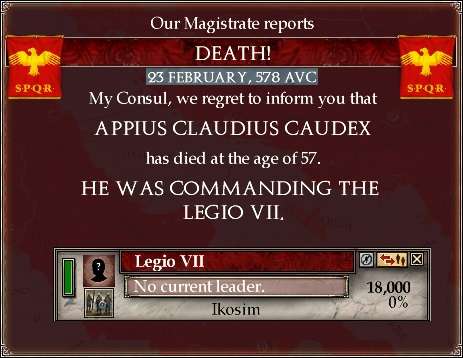

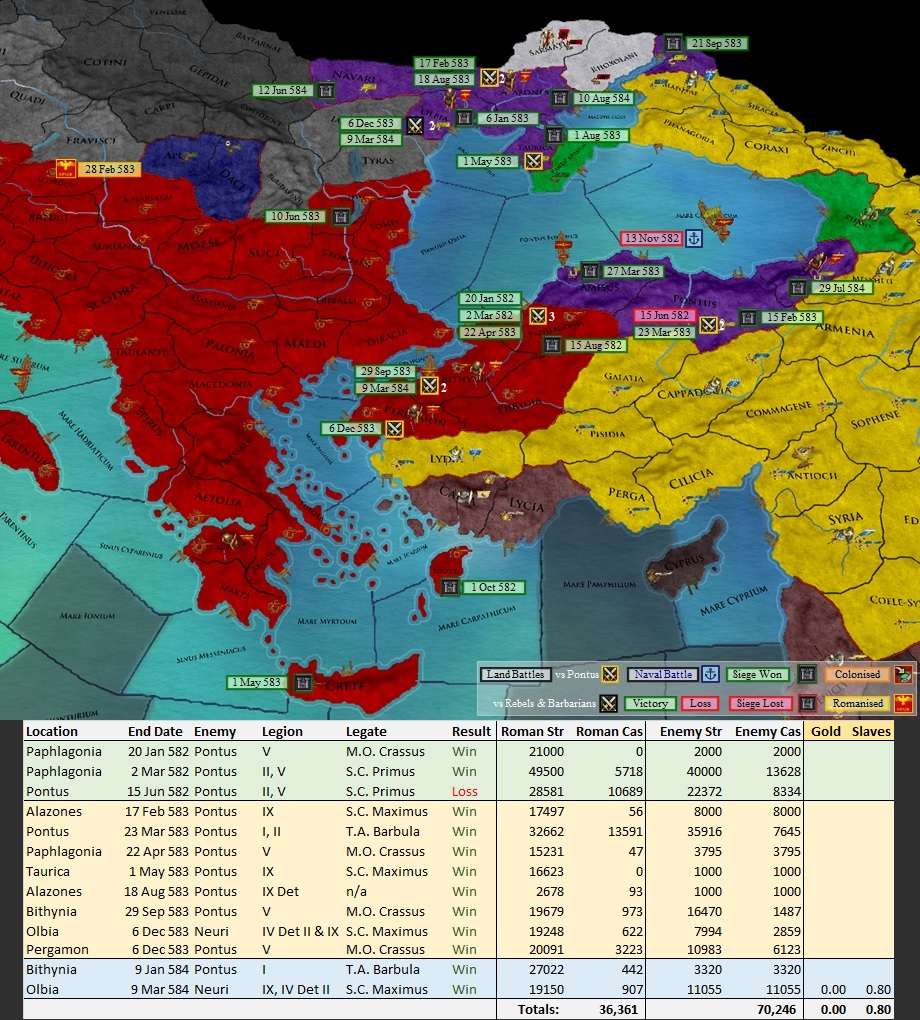

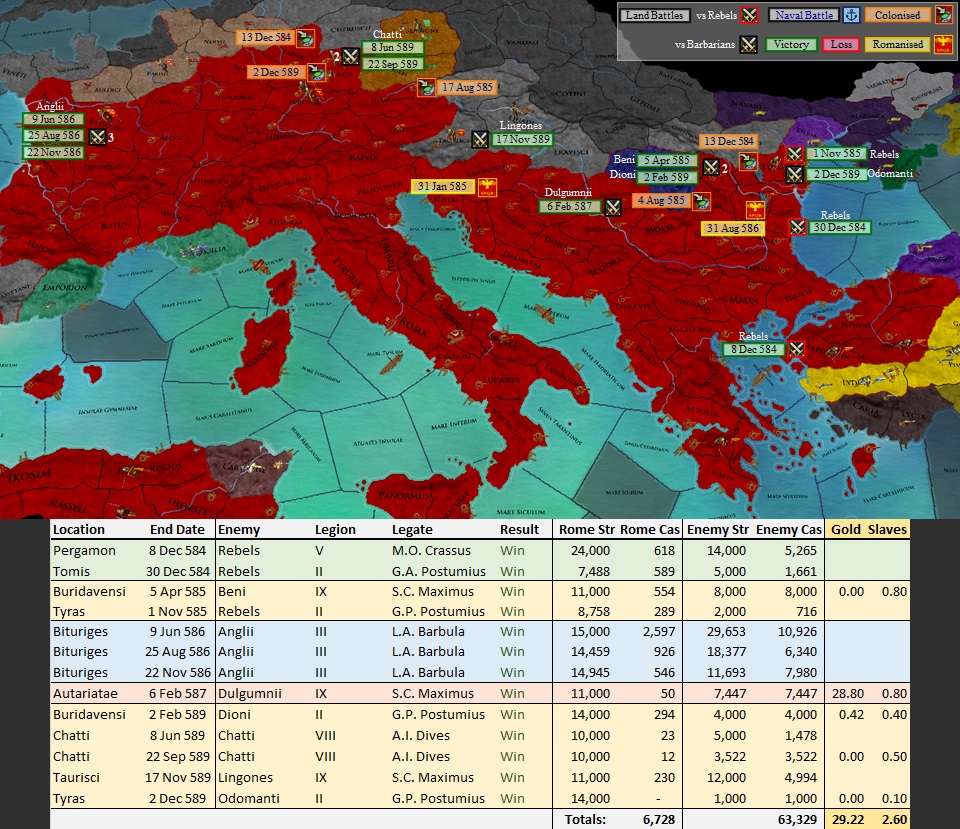

Despite an initial defeat, Roman Commander-in-Chief in the East, Aulus Claudius Caudex, had eventually completely crushed the two main Pontic armies in Illyria-Graecia and now sought to see off the last stragglers and subdue the Pontic provinces this side of the Propontis.

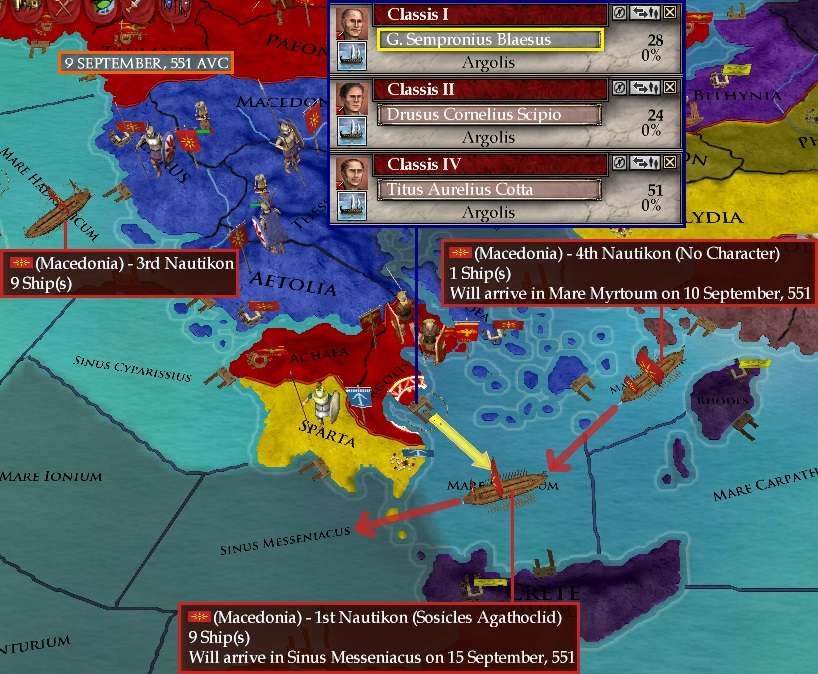

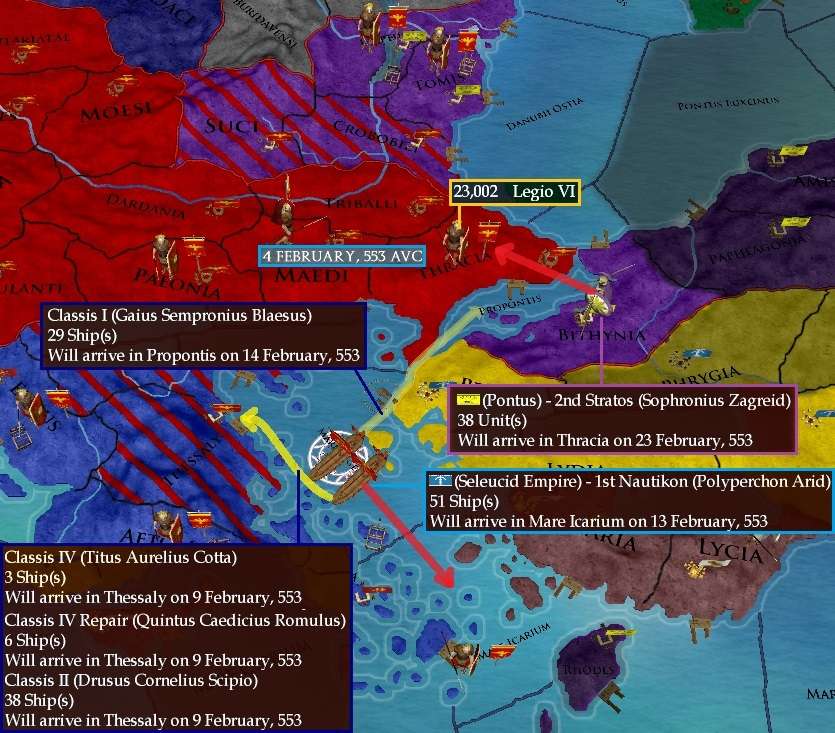

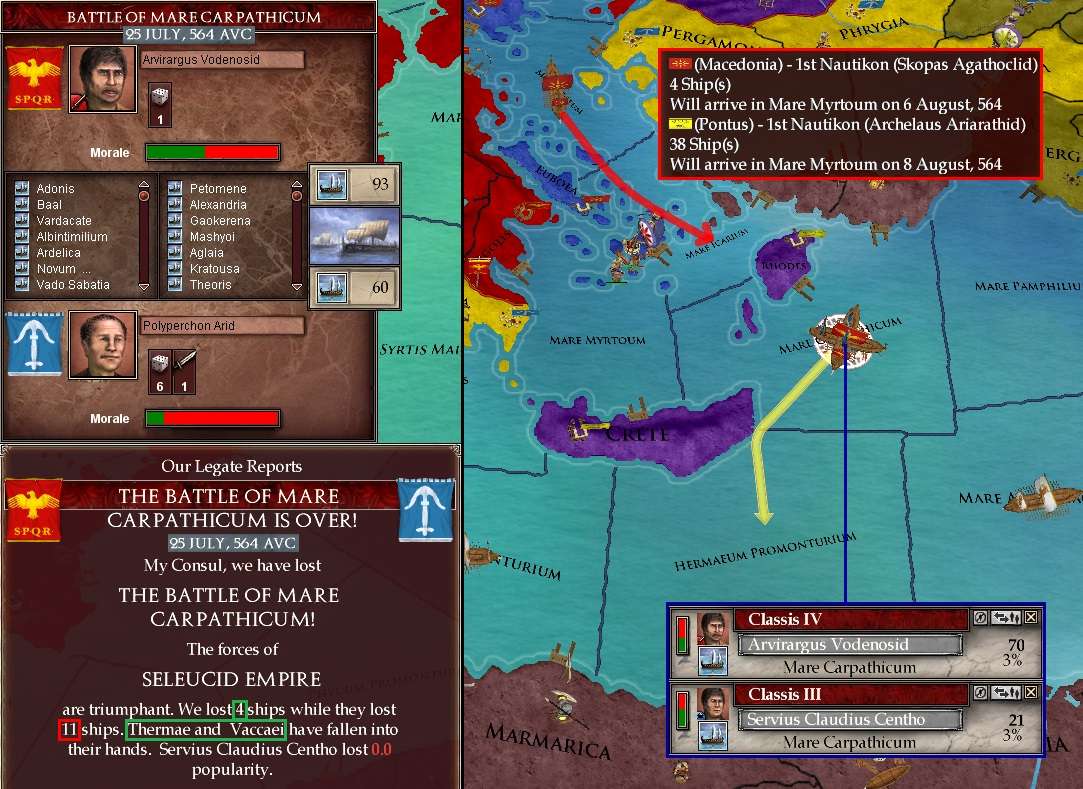

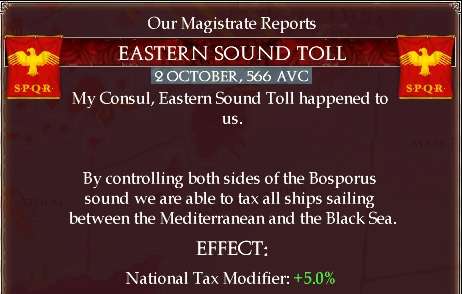

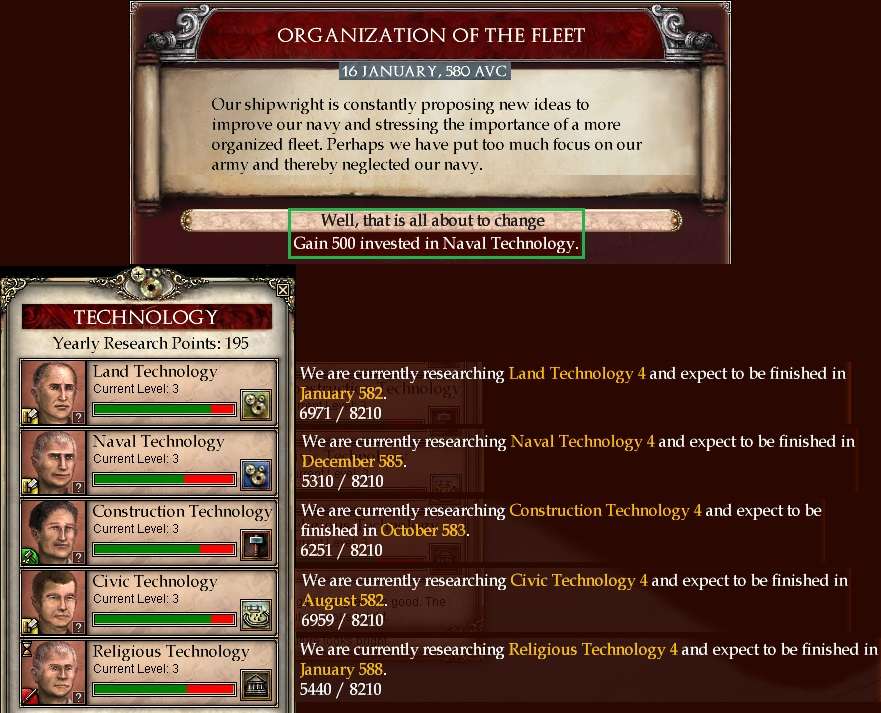

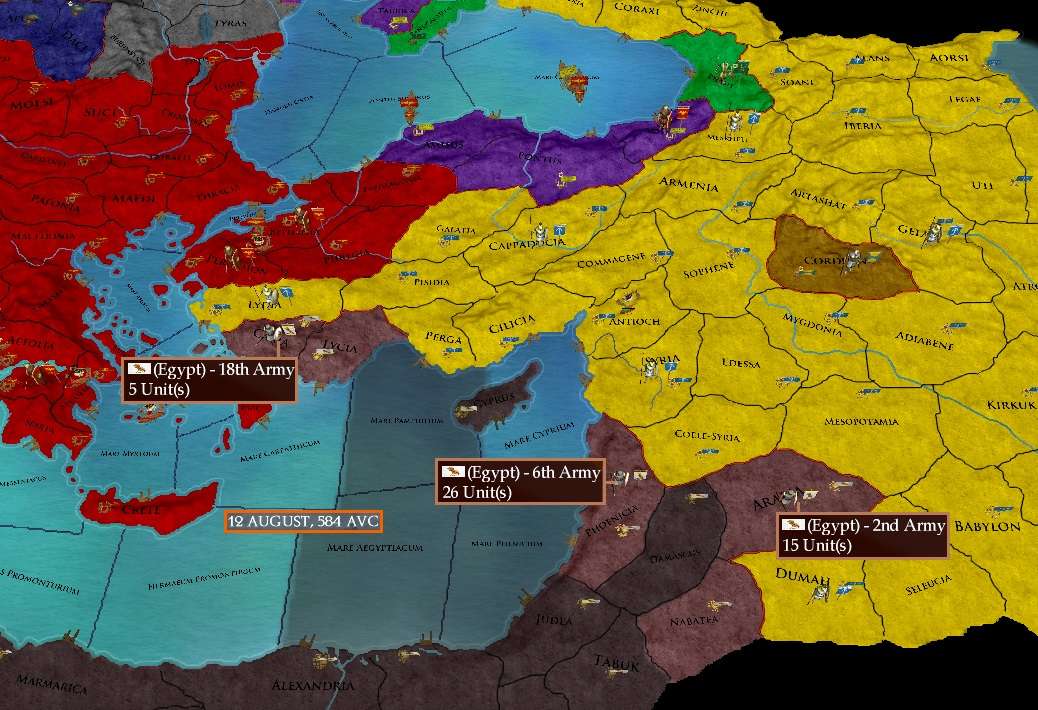

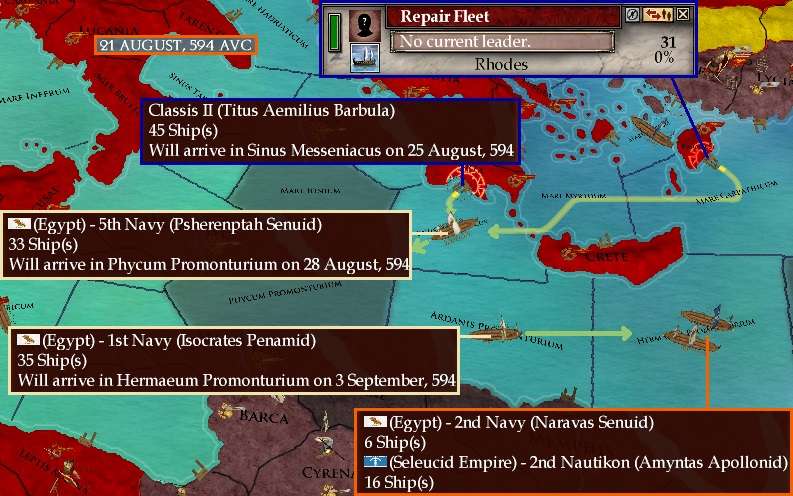

With Macedon and the Rebels now out of the war, the remnants of the Pontic fleet in the Mediterranean bottled up in the neutral Macedonian port of Epirus, and Egyptian fleets roaming the eastern Mediterranean, the war at sea would now be little more than an occasional sideshow.

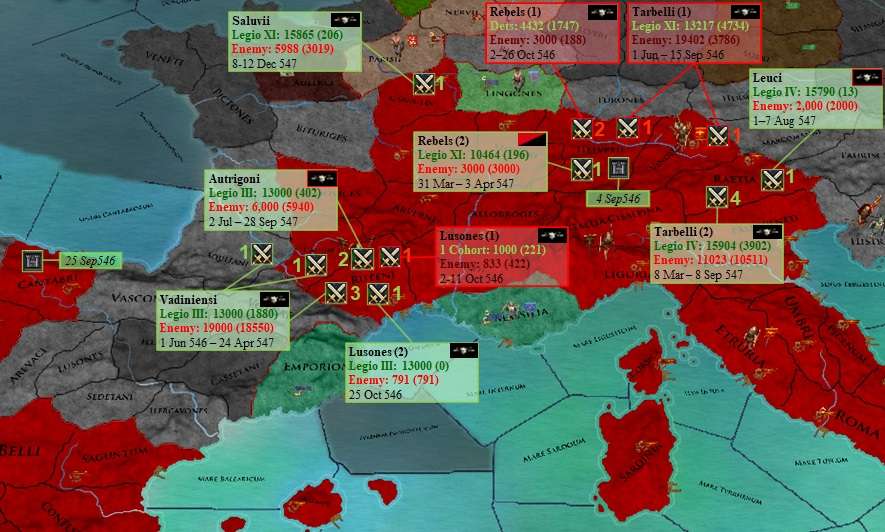

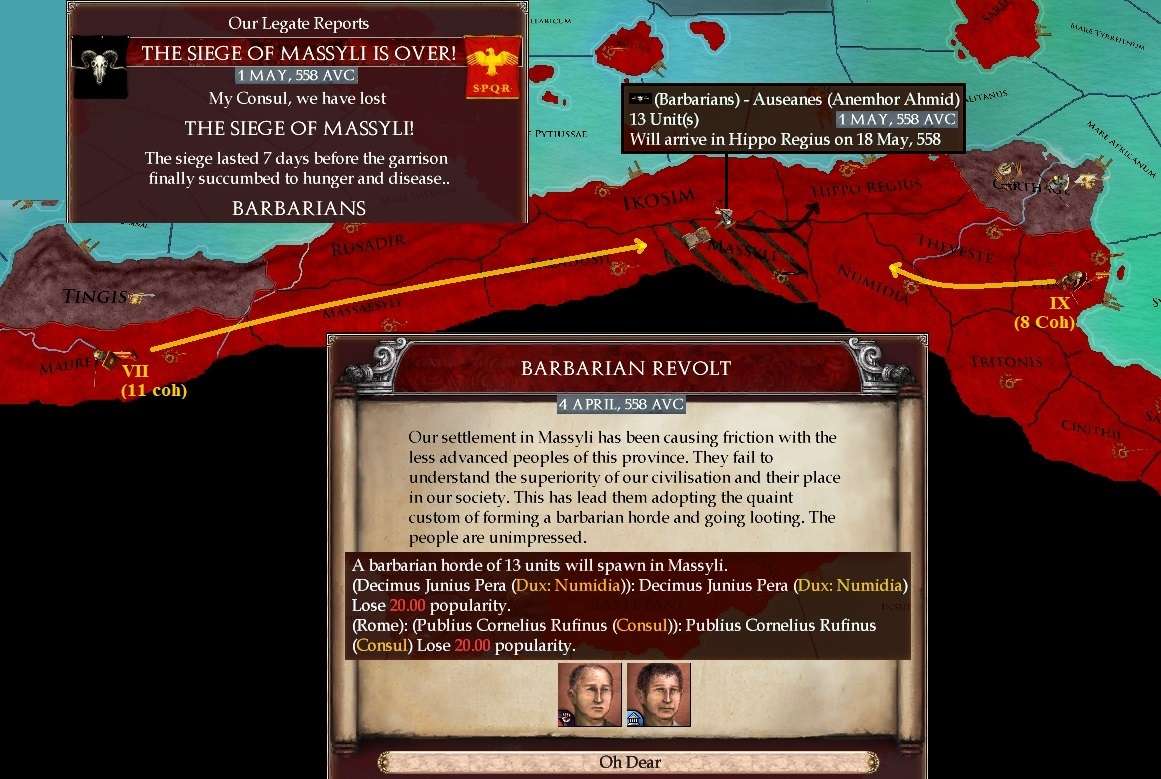

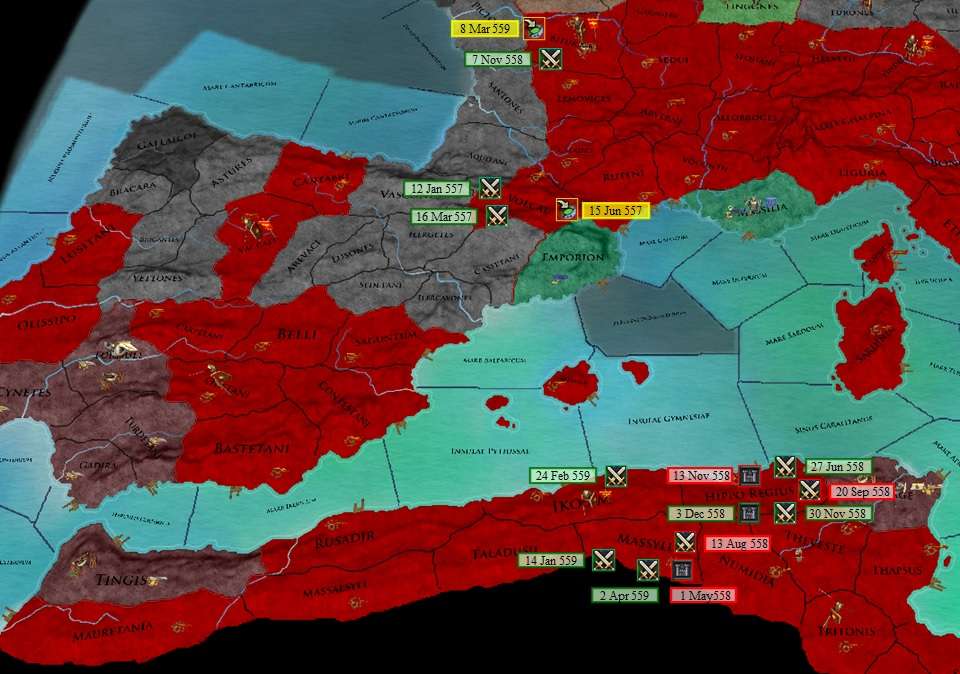

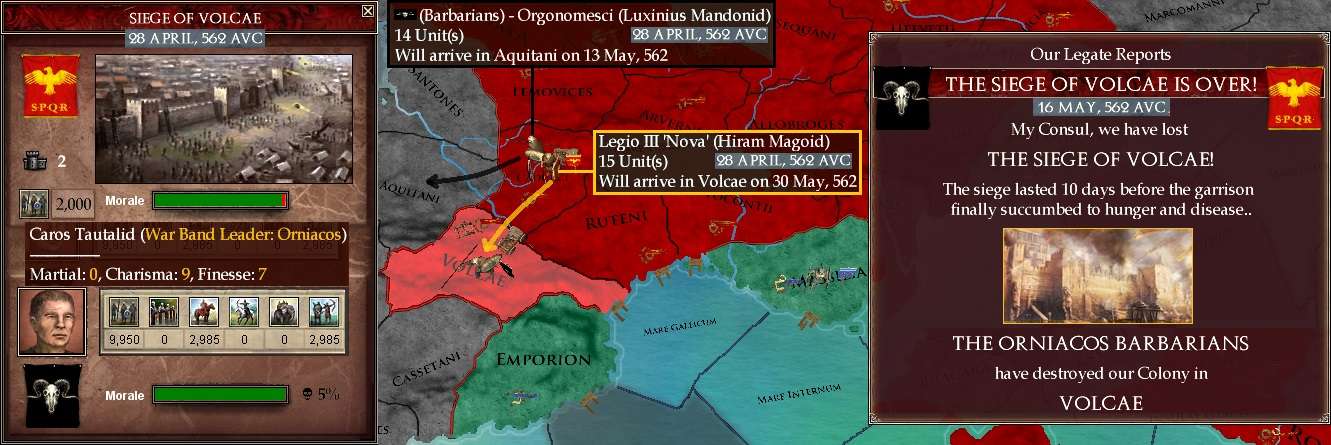

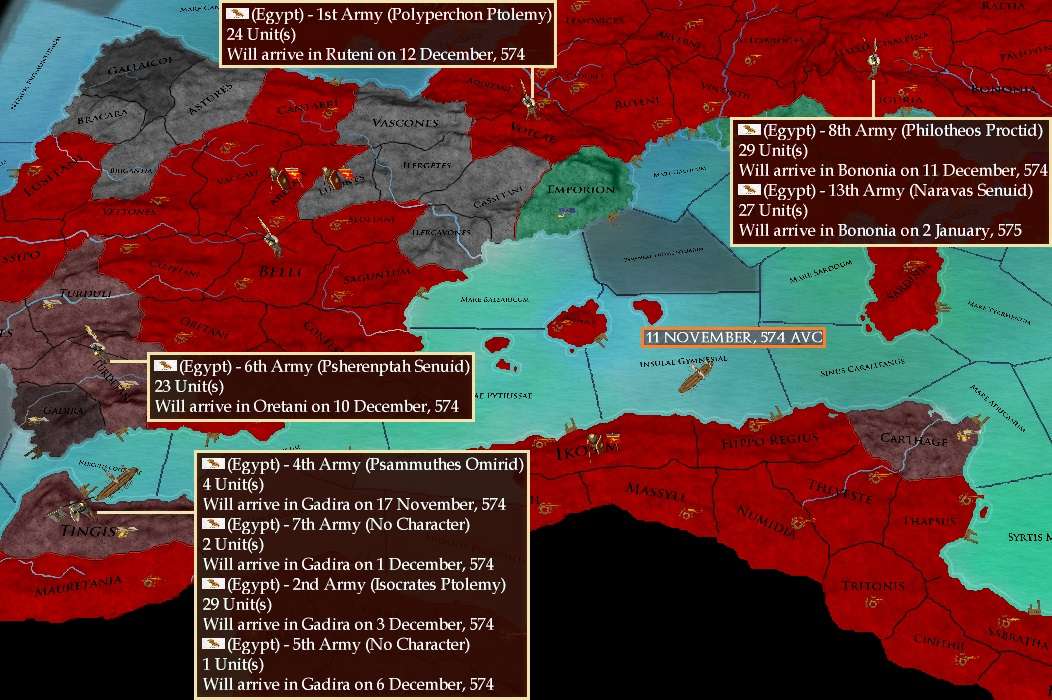

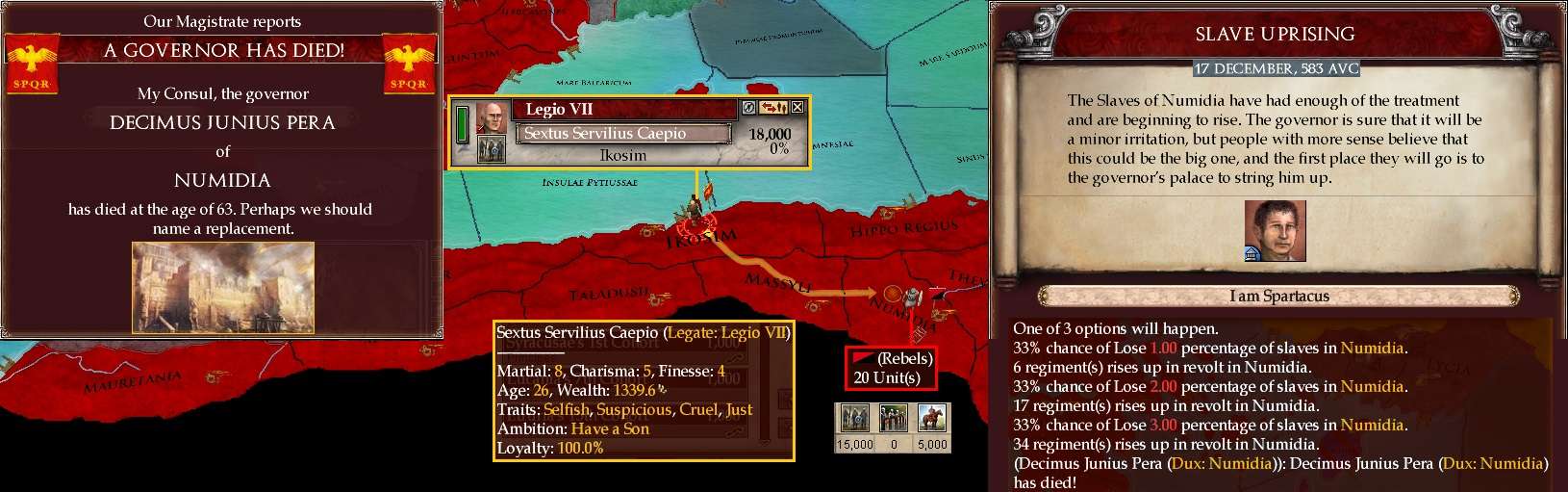

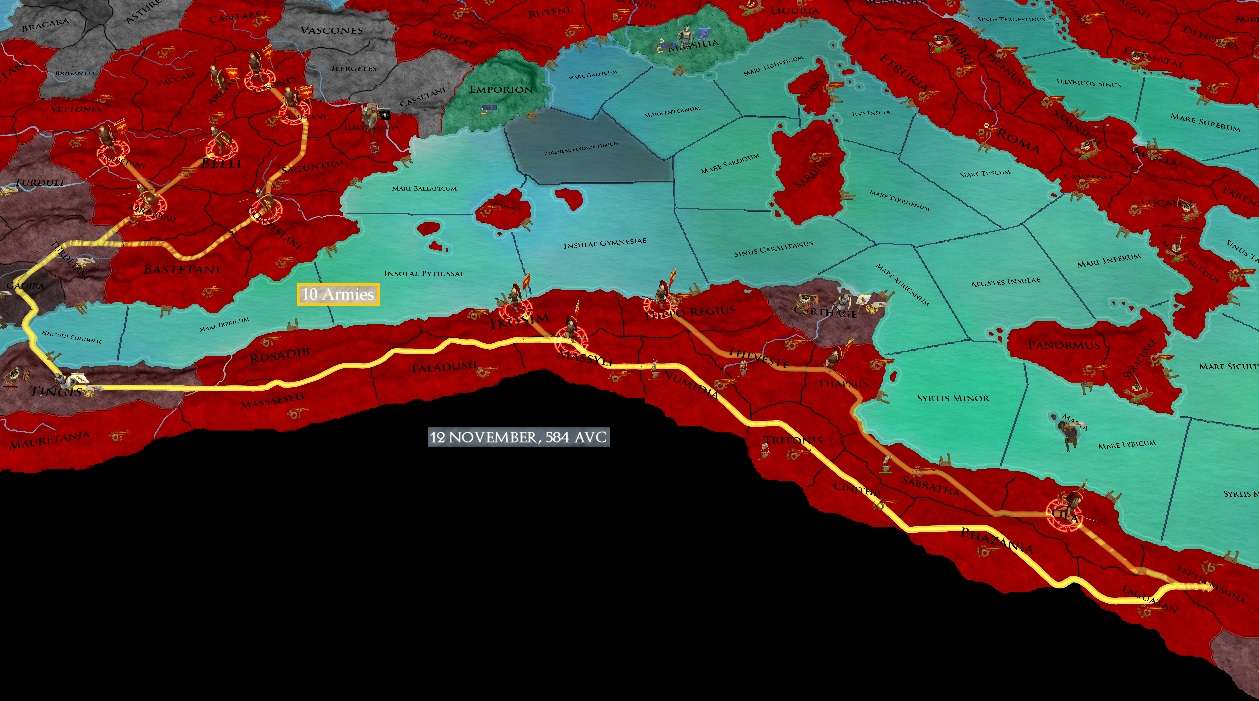

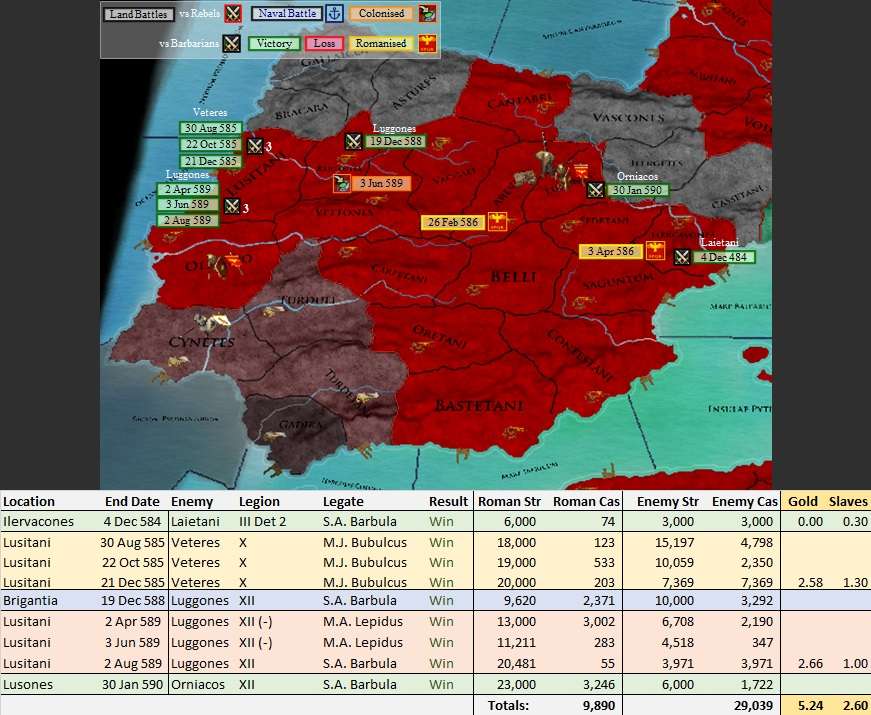

In Hispania, Gallia and northern Italia the threat came mainly from barbarian invasions and the occasional rebellion. The large slave revolt in Africa had been defeated at considerable cost at the Battle of Theveste in November 542.

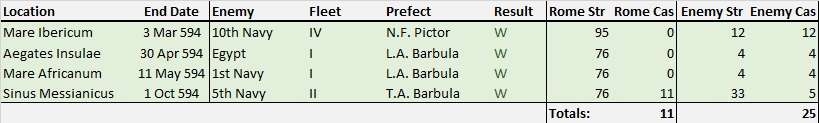

And in bureaucratic developments, Davidius Brentatius Officialis had been sent off as ambassador to Parthia, replaced as Principal Private Secretary to the Consul by the young grandson of Ursus, Bernardius Lanatus Deferens.

We will first review developments in Rome and the west, before finishing with the events of the ‘main game’: the Great Eastern War.

§§§§§§§

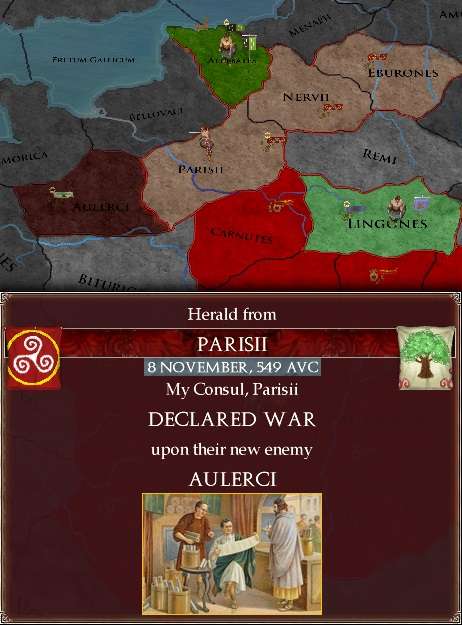

1. Roma and the West

1. Roma and the West

January-April 543

Throughout January, the Consul M.V. Maximus was still in the early days of his long march back west across Africa with Legio VII to deal with the small barbarian uprising in Mauretania. The latest pirate fleet was found and destroyed in Mare Gallicum on 12 February, capturing one and sinking the other four.

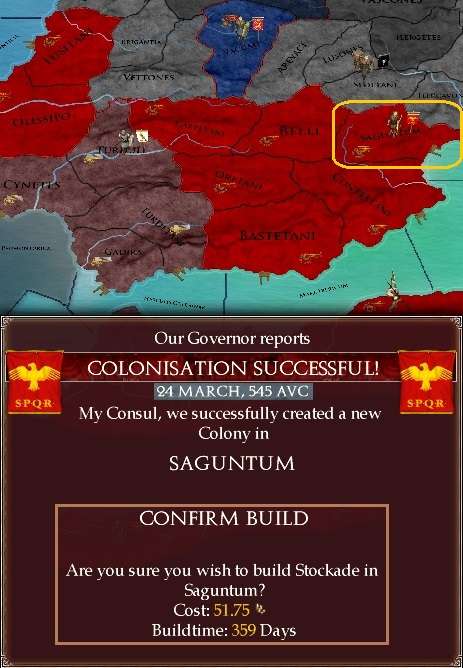

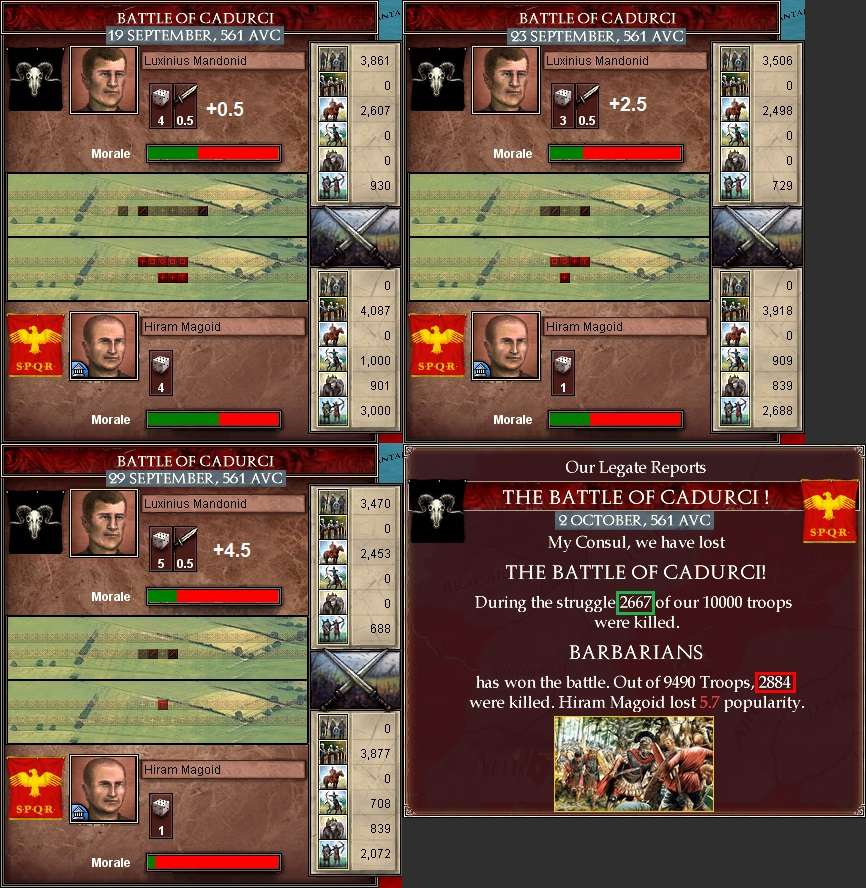

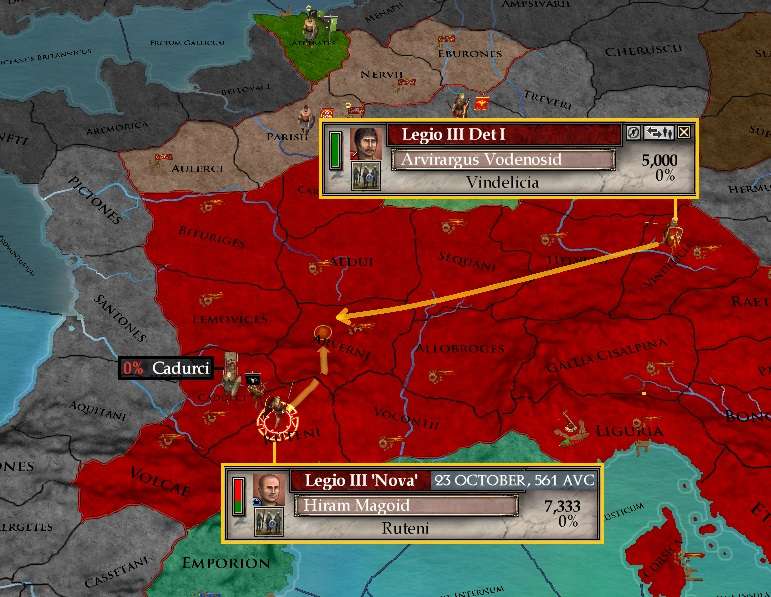

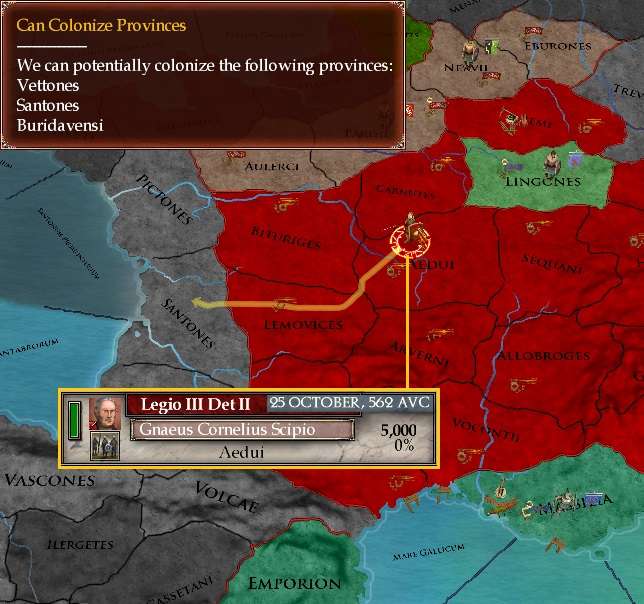

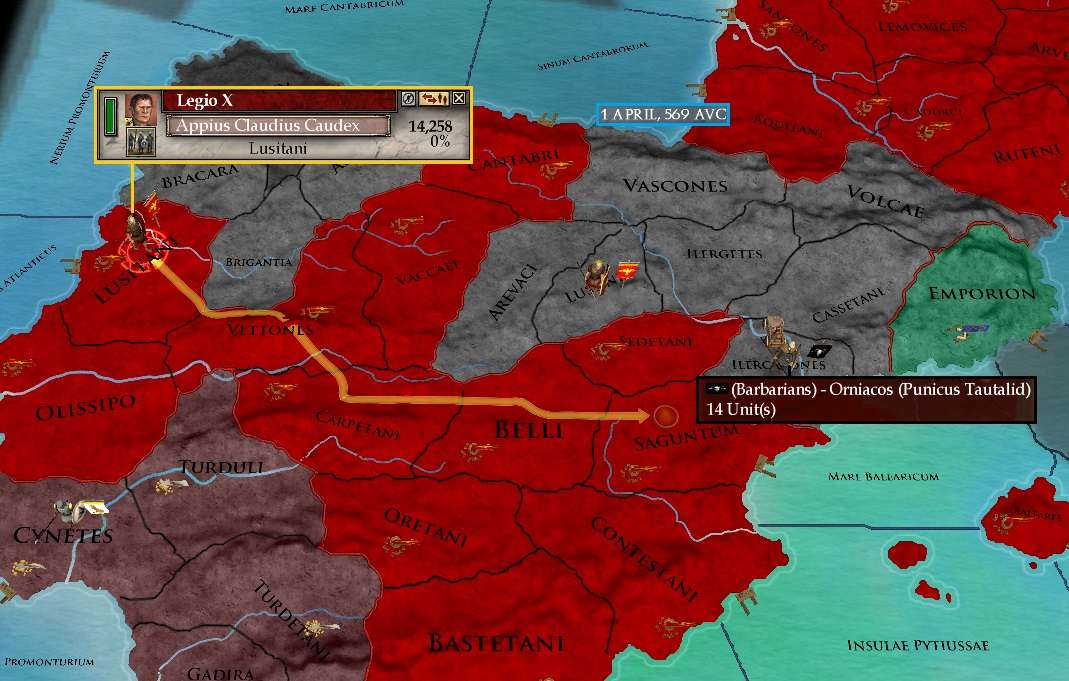

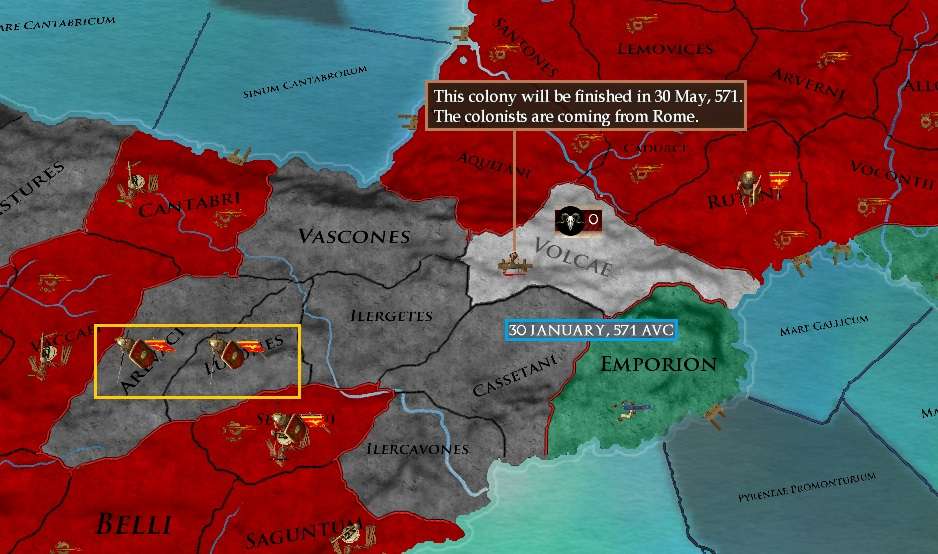

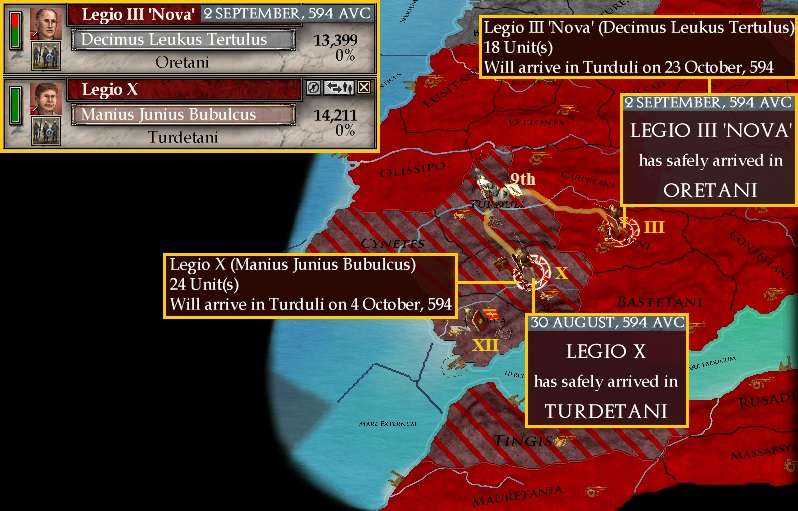

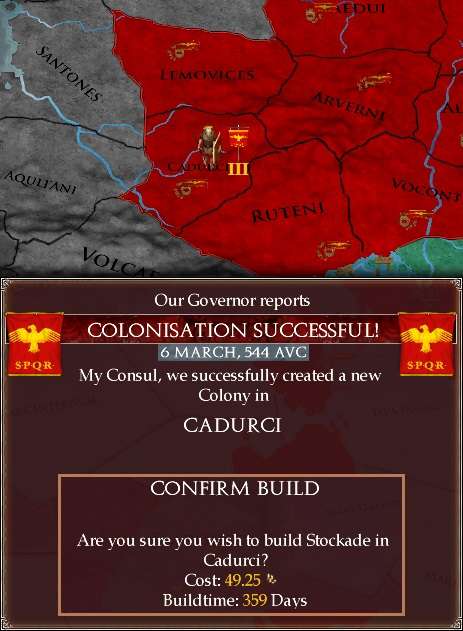

By 21 March, two possible new colonisation opportunities had arisen. In Aquitania, Cadurci was available – but the barbarian strength there (five) was too great: Legio III (Hiram Magoid, 12 cohorts) was tasked to incite and destroy them. In Hispania, Saguntum [in OTL the flash point for the 2nd Punic War at around this time] had an even greater barbarian presence (14) - too large it was felt for Legio X (nine cohorts, stationed in the new colony of Carpetani) to deal with as it stood. A cohort of regular principes was put in training in Oretani.

The former Consul Publius Valerius Falto (Religious faction) died on 5 April at the age of 71. A modest funeral was held.

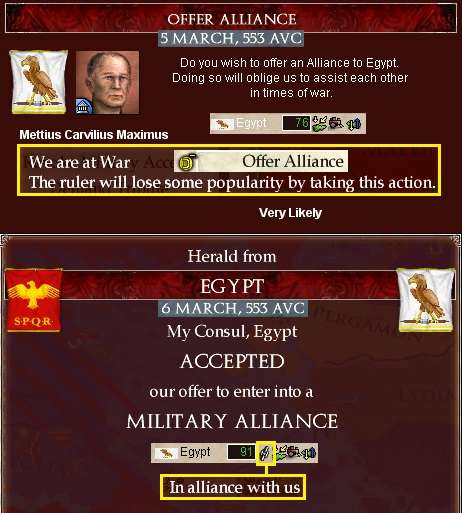

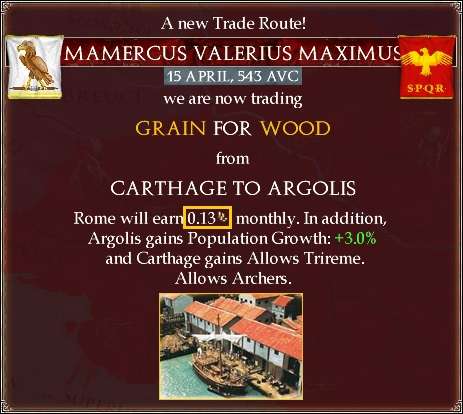

A lucrative new trade deal was done with the Egyptians on 15 April for the recently acquired Argolis.

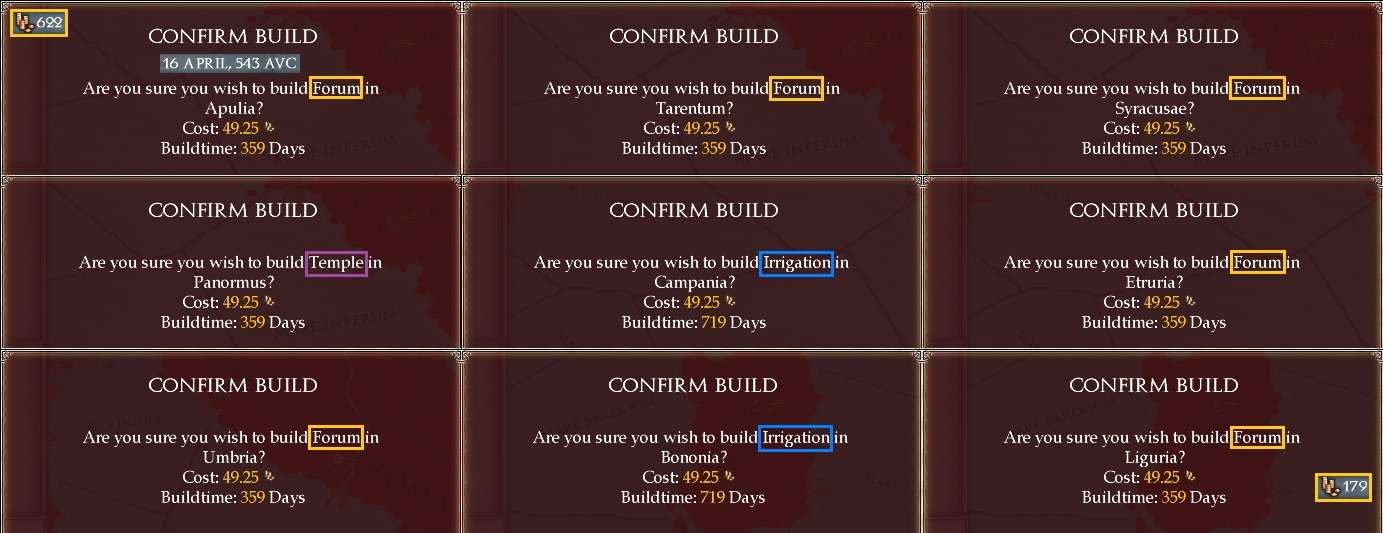

“Ah, look here, Bernardius,” said the great bureaucrat, flourishing the response and beaming. “We shall be embarking on the greatest building program in the history of Rome! Trade especially will flourish.”

“Nonsense, Bernardius, a complete coincidence,” said a simultaneously cross and defensive Humphronius. “Simply recognition of a long career of public service. Switching the subject completely, I have a dinner party tonight with a few construction magnates and leading traders. The Greek wine and ocelot spleens should be particularly good, I hear.”

“A simple gesture of appreciation for long service, Humphronius?” said a chastened Bernardius.

“Precisely, Bernardius.”

By the end of April Legio III was in Cardurci, doing their best to taunt and provoke the local barbarians into rising (and suffering 5% attrition per month in doing so).

§§§§§§§

May-August 543

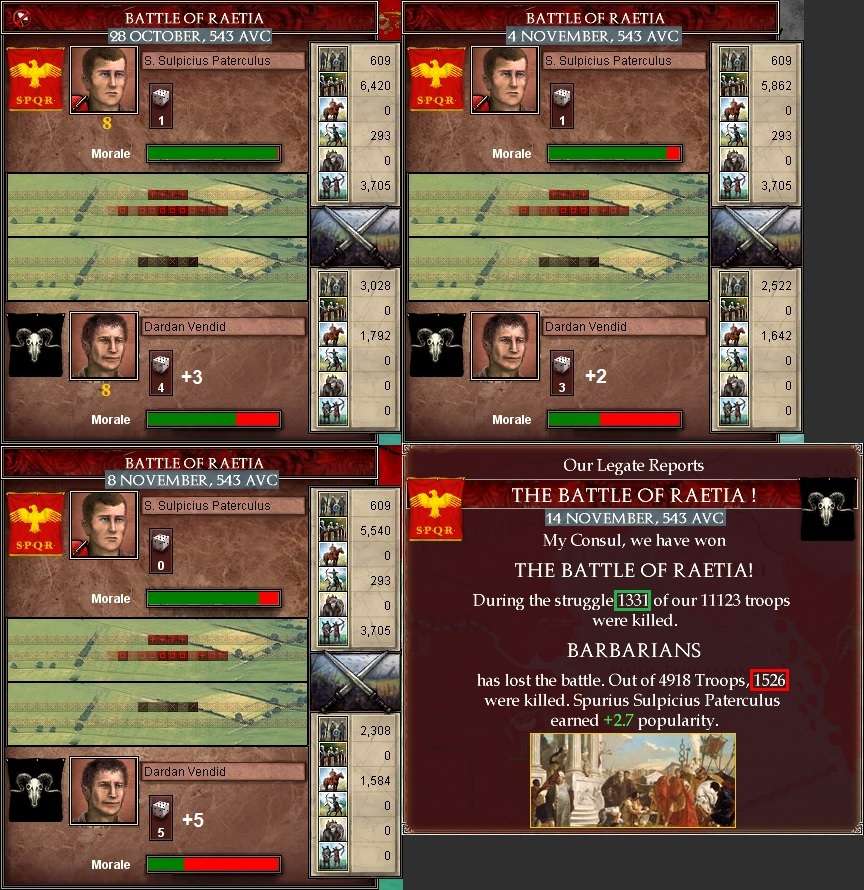

The year before, Legio IV had been sent off to the Eastern War and Legio III was now in Cardurci, so there were no troops stationed anywhere near northern Italia, when a small barbarian force – 6,000 Caduscii – was sighted in Marcomanni on 3 May, heading for Raetia.

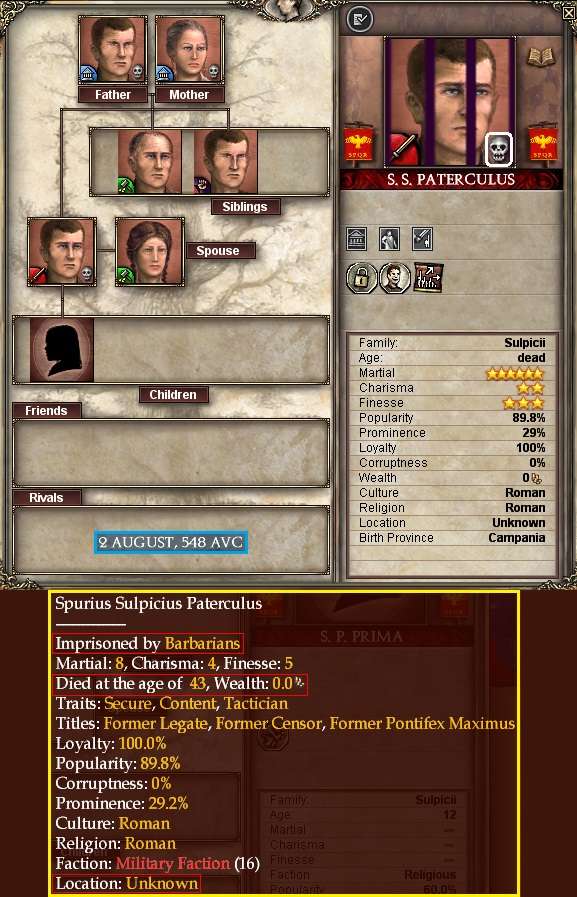

There was no immediate Roman reaction: they hoped the stockade in Raetia could hold out for many weeks or months, giving them time to arrange a response, as (we shall see below) action in Illyria in the Great War was still a distraction. But by 31 May, a new legion – Legio XI – was formed in Illyria (more details in Section 2 below) and, under S.S. Paterculus [Martial 8], began marching to northern Italia to deal with these irritating interlopers.

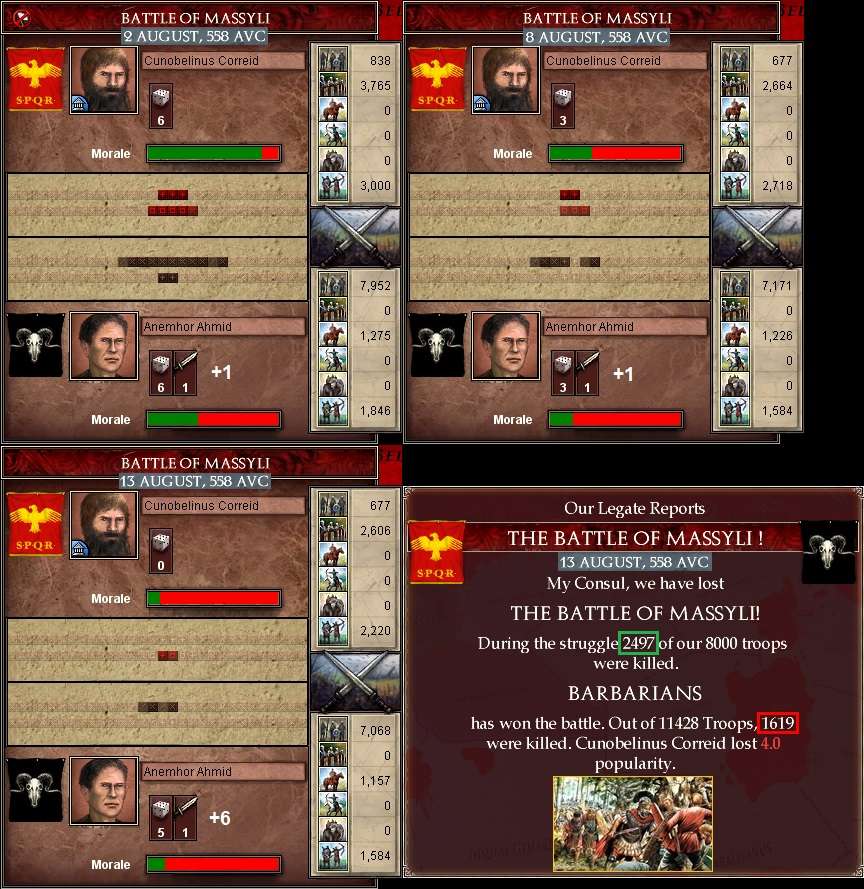

New core provinces were declared on 2 June in the old African conquests of Ikosim, Hippo Regius, Taladusii and Massyli. Which must of course “be defended until the last drop of peasant blood”, Humphronius observed.

The Caduscii arrived in Raetia on 7 June and began a siege – they did not have the strength to risk an assault.

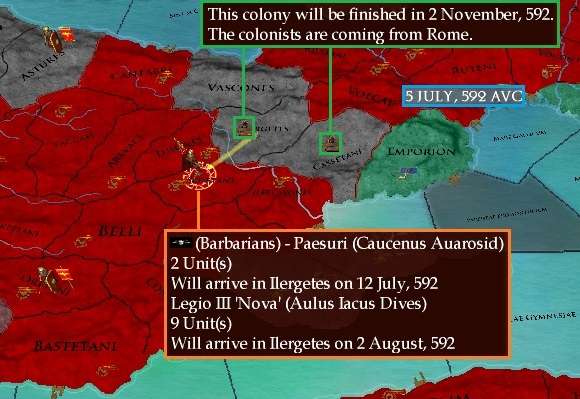

On 12 July, important news was welcomed from Carpetani: the new colony was now protected by a stockade. Given there was an immediate barbarian threat, it was important it be protected properly if Legio X was to eventually march east to try to pacify Saguntum. The new principes cohort had just finished training in Oretani and now a cohort of auxiliary archers was put into training in Lusitani.

On 5 August, Consul Maximus finally reached Mauretania with Legio VII (15 cohorts), to exact vengeance on the 2,000 barbarians who had damaged his popularity with their uprising. He won in just three days, losing only 31 men, killing all the barbarians and seizing 3.11 gold and 2,000 slaves in loot.

§§§§§§§

September-December 543

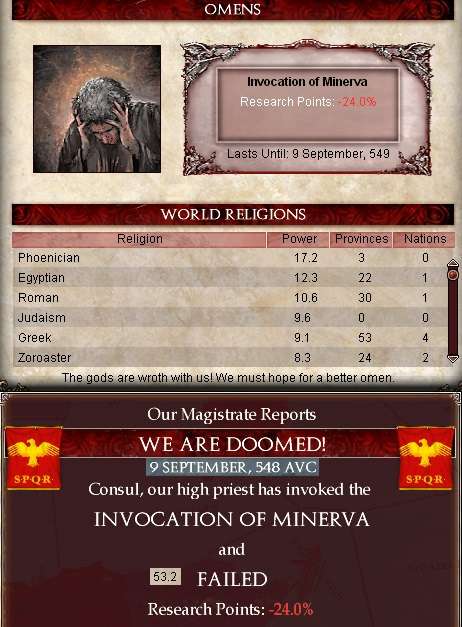

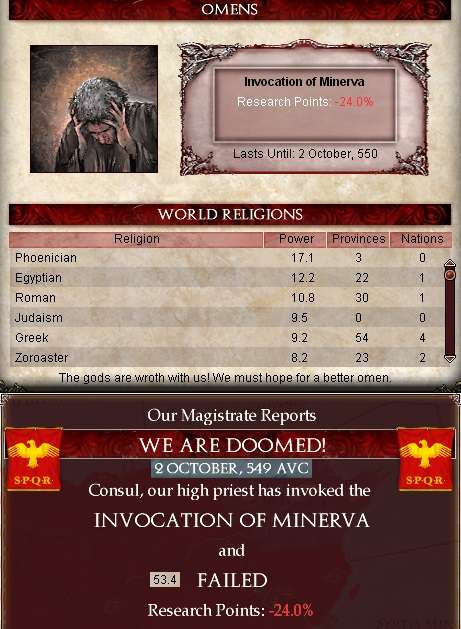

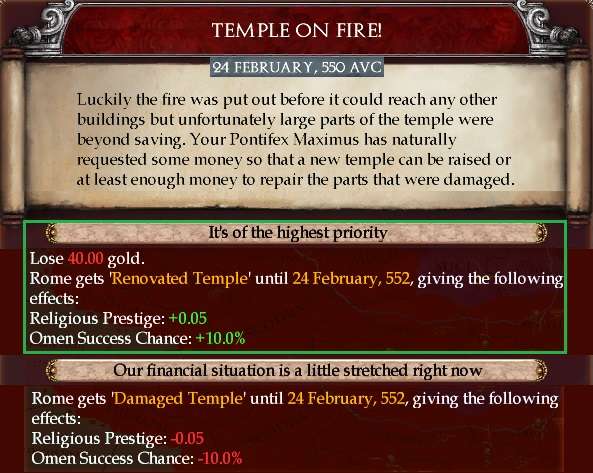

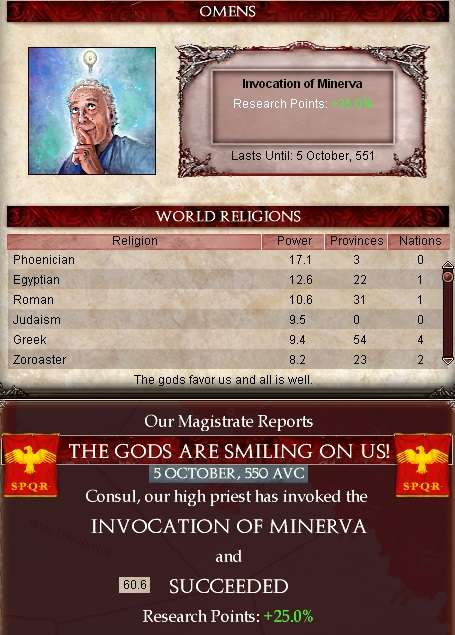

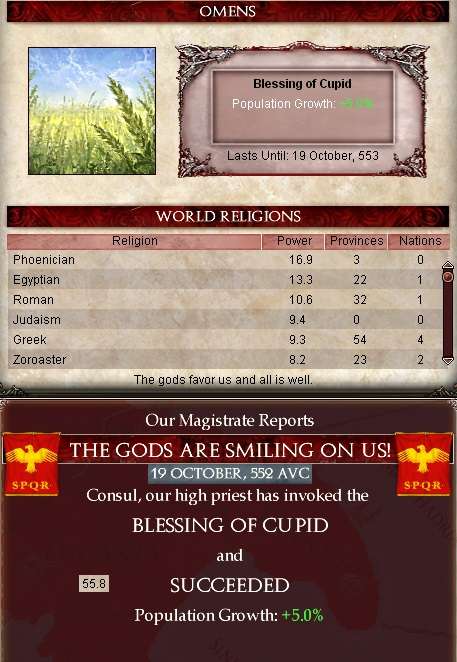

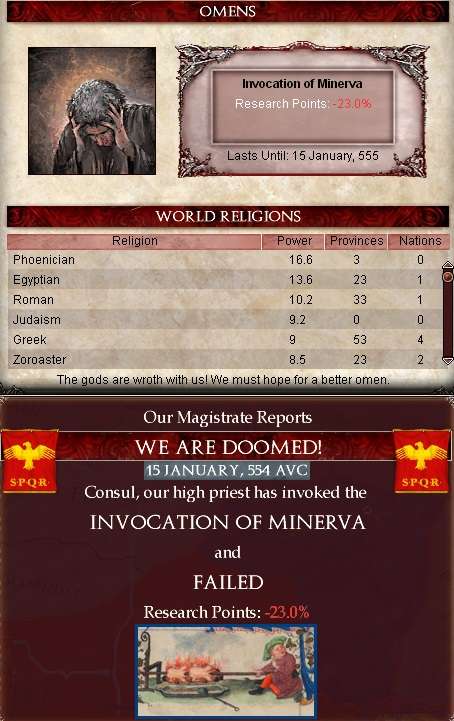

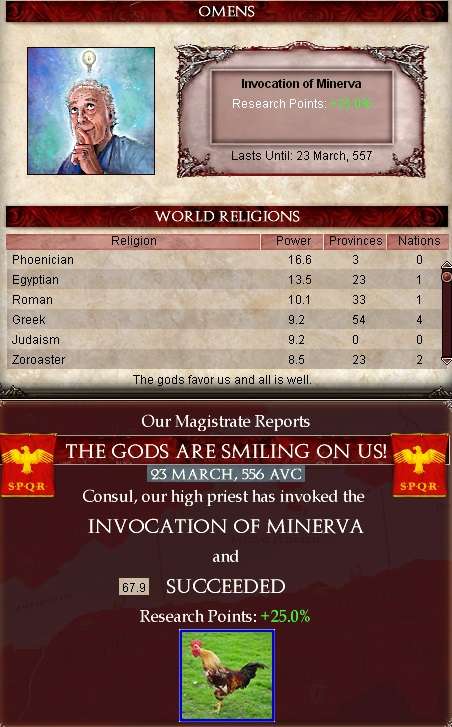

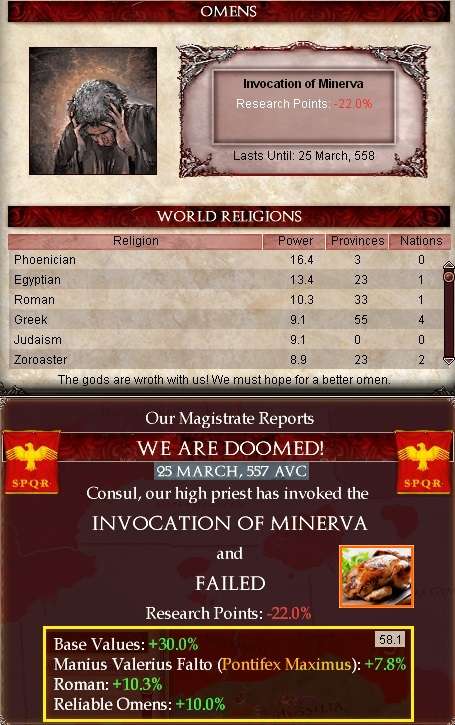

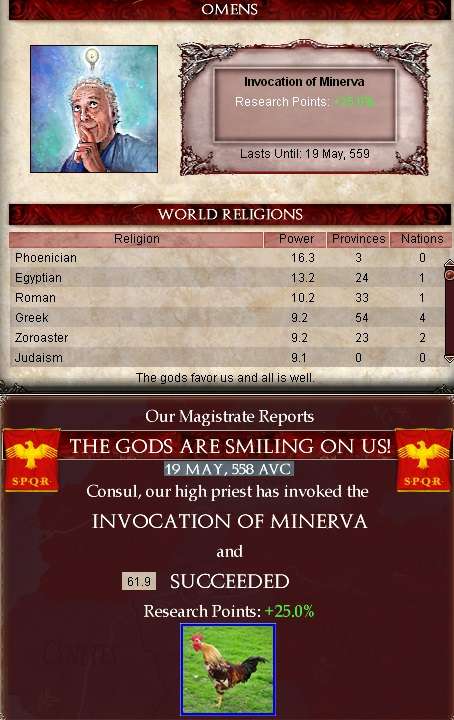

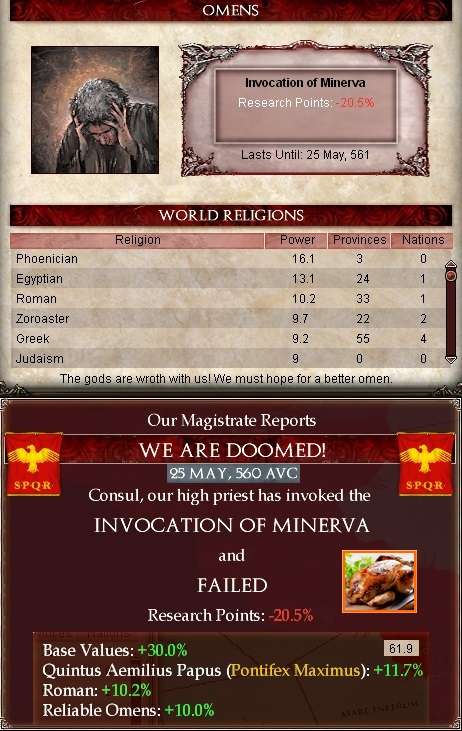

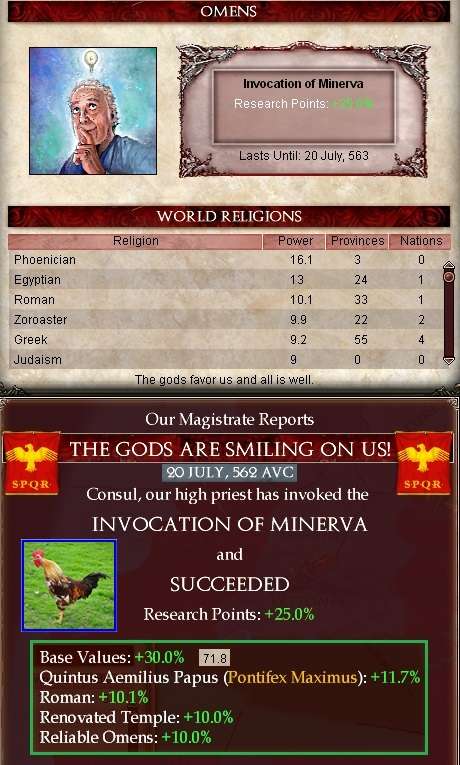

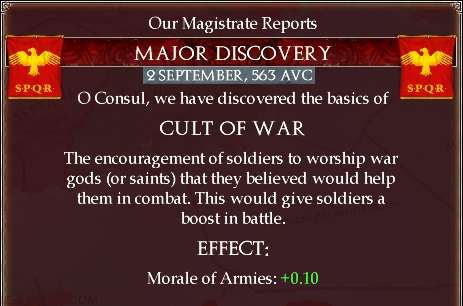

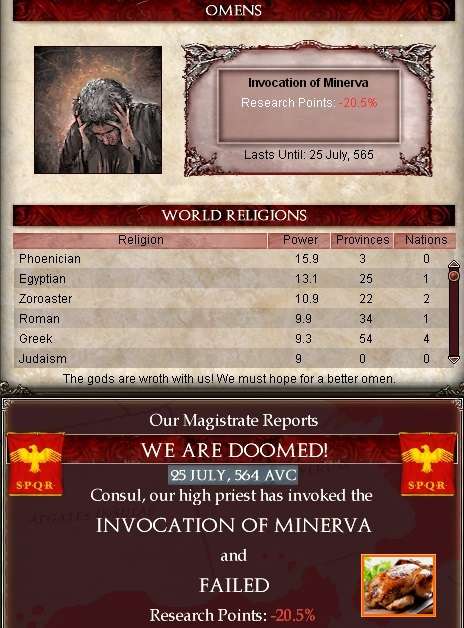

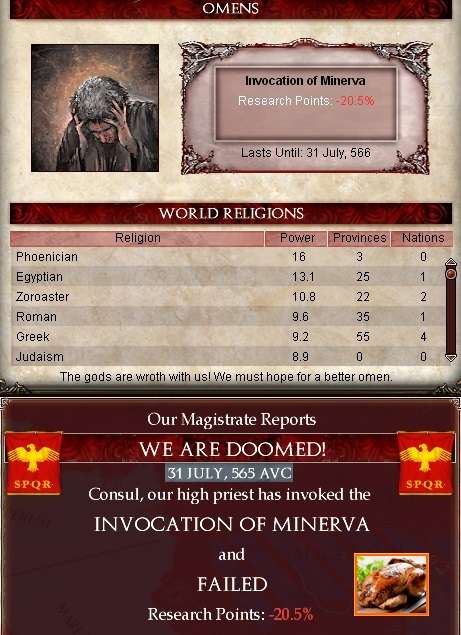

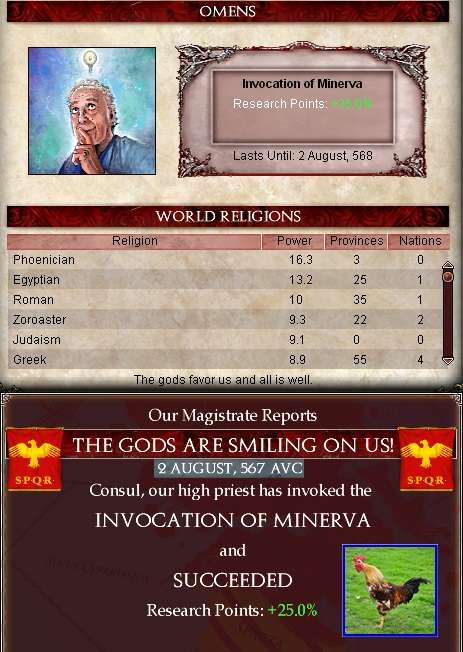

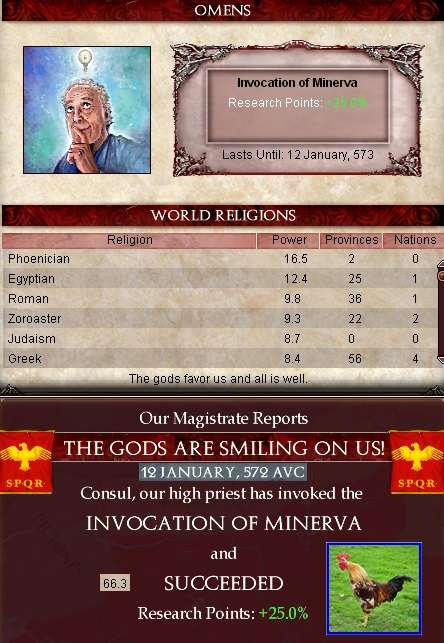

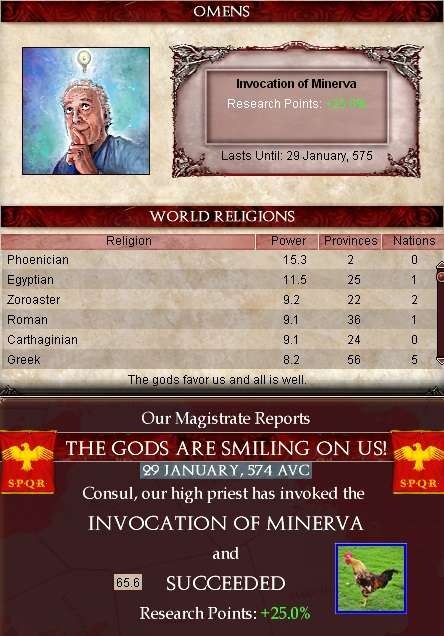

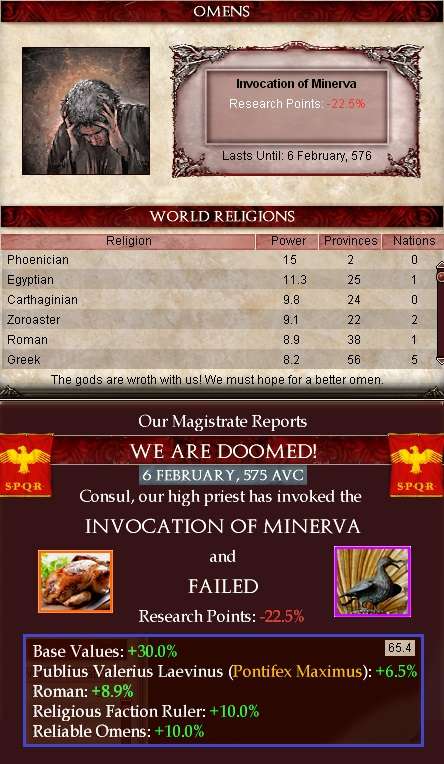

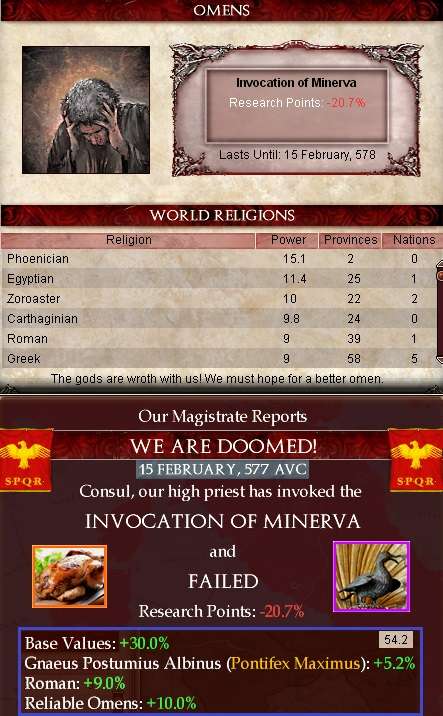

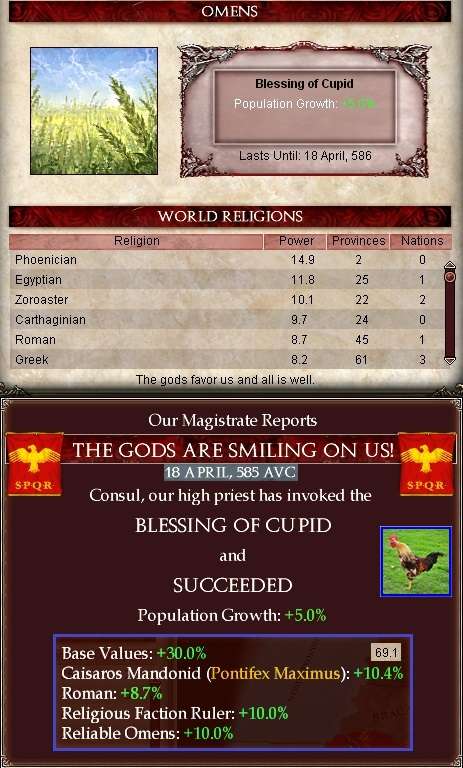

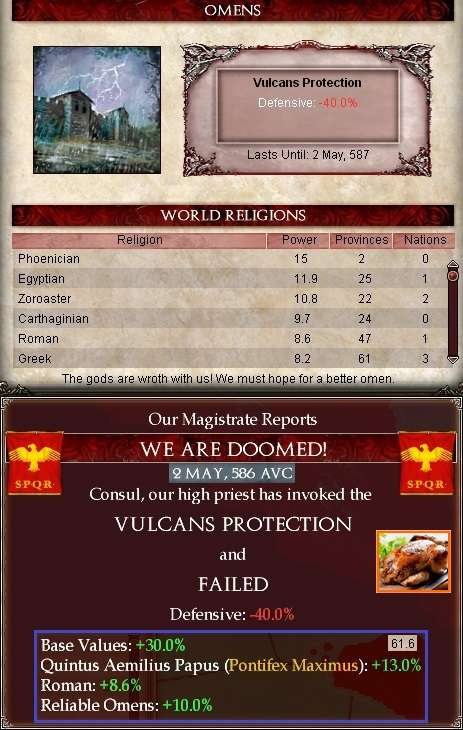

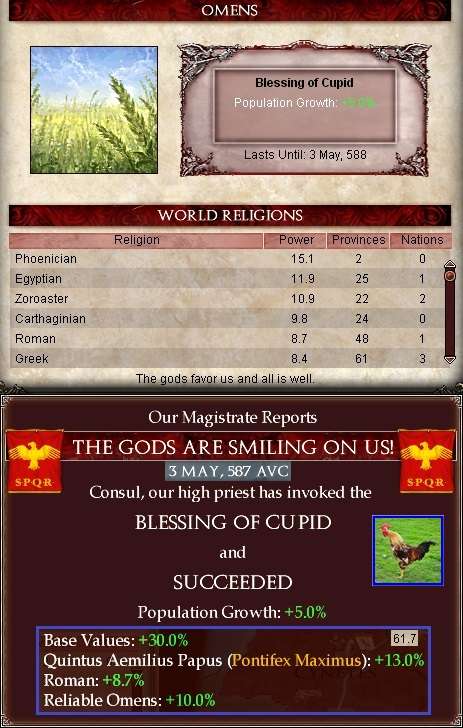

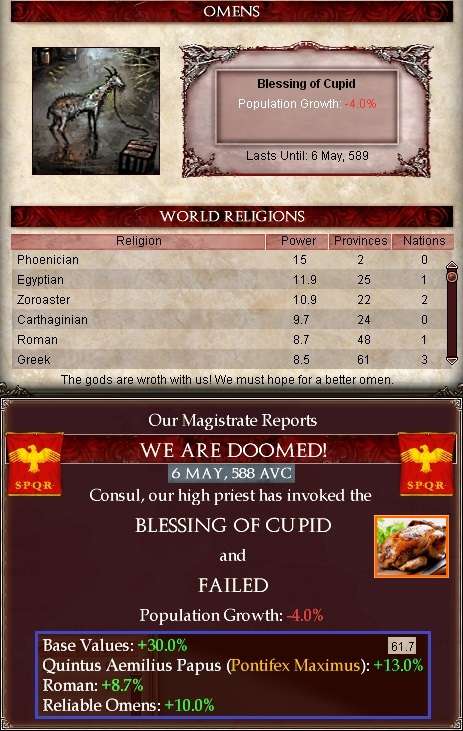

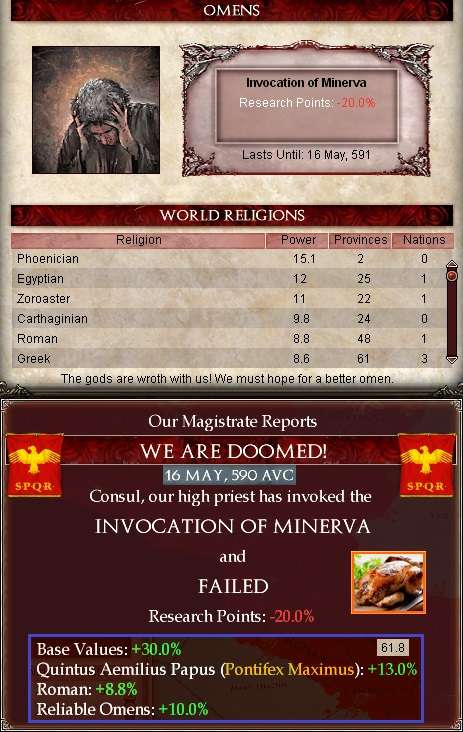

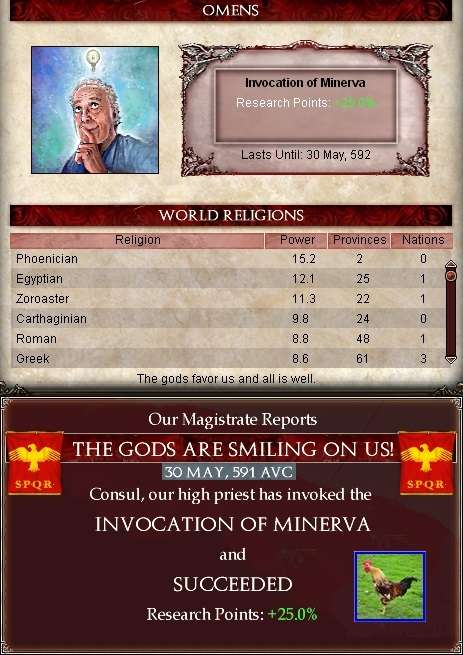

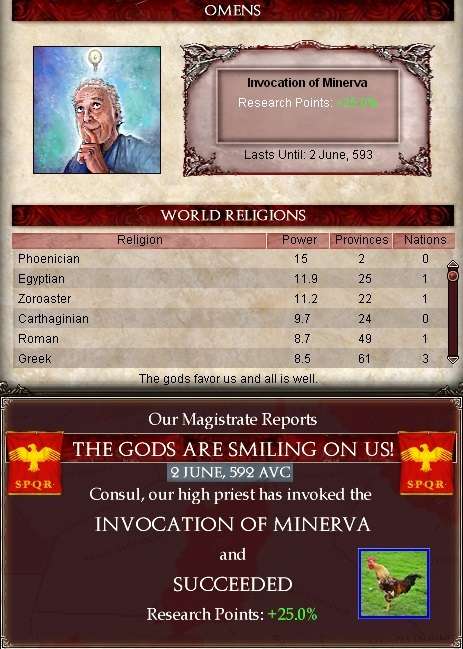

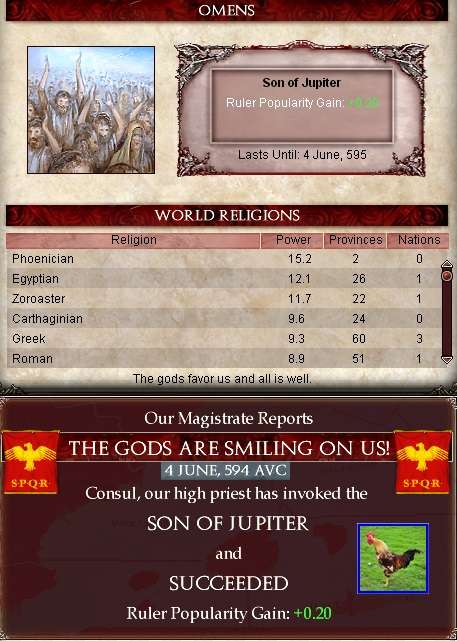

The poor run of omens continued as the uncooperative chickens dashed off after release without pecking at the grain piled in front of their cages.

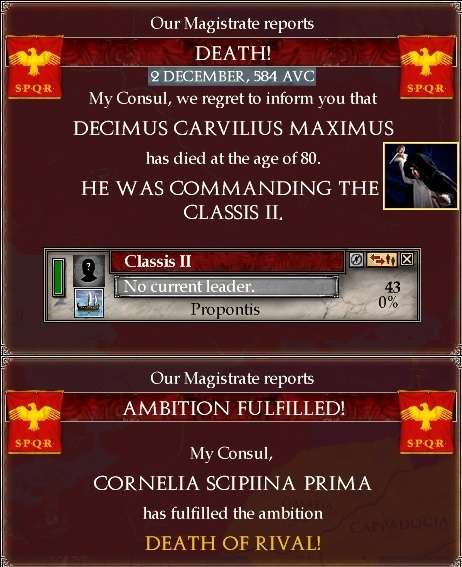

In early December another pirate fleet appeared in Syrtis Minor: Classis II (D.C. Scipio, 22 ships) was sent from its base in the Baleares to deal with them. They would be destroyed in Mare Africanum on 1 February the following year .

§§§§§§§

January-July 544

Perhaps resentful that his province had not been included in the great building splurge, the local Governor of Massaesyli (S.F. Gurges) built one there with local funds on 17 January. Three days later, the Caduscii turned up in Gallia Cisalpina – Paterculus began the march across from Raetia to eject them.

Over in Hispania, Legio X (up to 11,000 men in strength with recent reinforcements) left Carpetani (now protected by a 2,000 man garrison in its stockade) for Saguntum to do some barbarian-baiting.

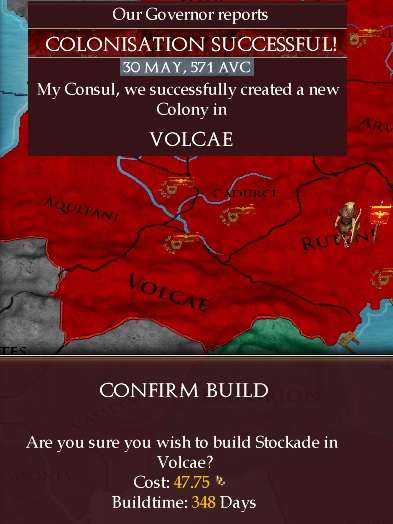

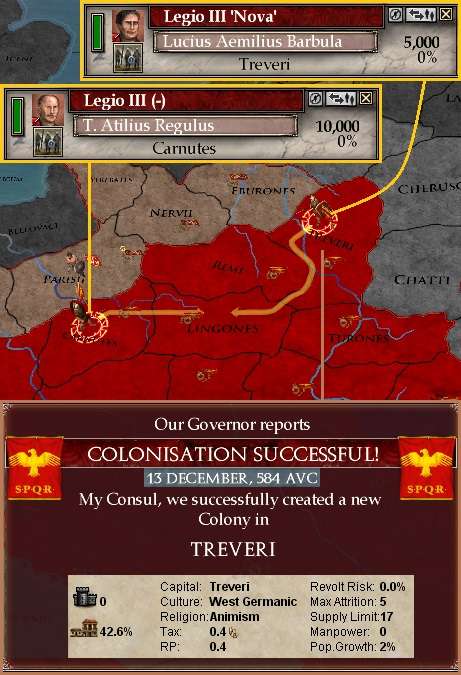

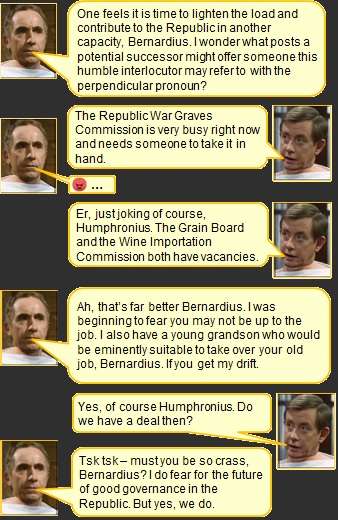

In early March, Cadurci became Rome’s latest colony and of course construction of a new stockade was soon begun.

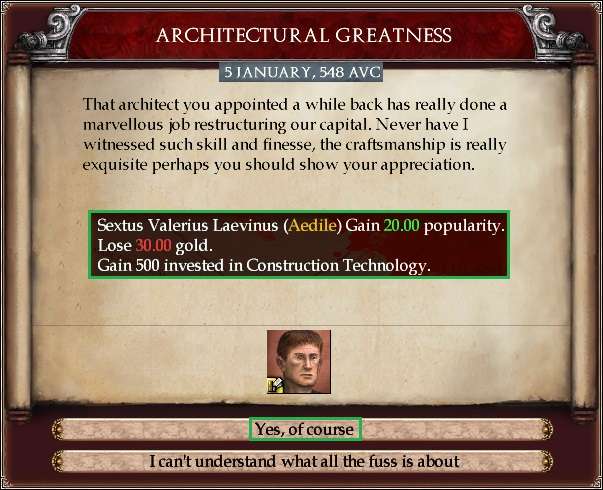

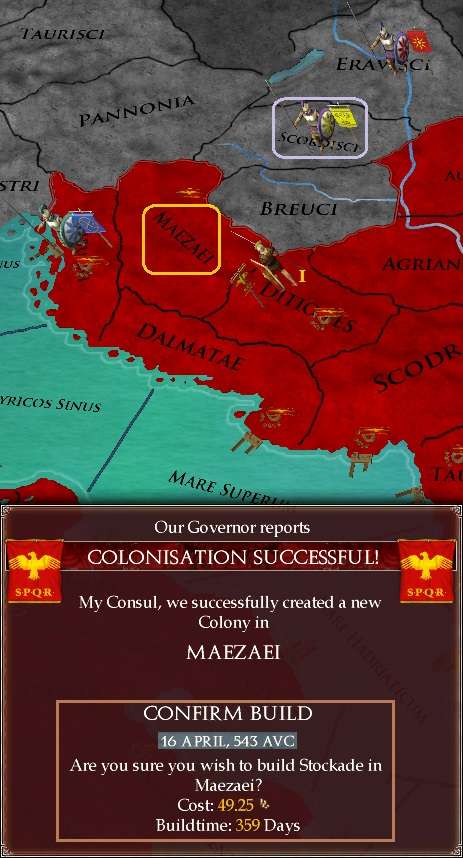

11 April saw the completion of most of the building program, with six fora, one stockade (in the new colony of Maezaei – see Section 2) and a temple in various provinces. By 12 May, a range of new domestic and foreign trade routes were created from all the extra trade opportunities the new fora permitted. Humphronius moved into his new mansion on the Palatine the same day. A pure coincidence, of course.

A new pirate menace arose in the northern Adriatic on 14 April. A.P. Albinus set out with 13 ships of Classis III from nearby Tarentum to destroy them, which was accomplished in Illyricos Sinus without fuss by 18 May.

Two days later, Legio X was in Saguntum, insulting the manliness and fighting spirit of the local tribal chieftains, among other provocations. As a bonus, they found enough local supply to avoid the usual attrition of encamping in barbarian lands.

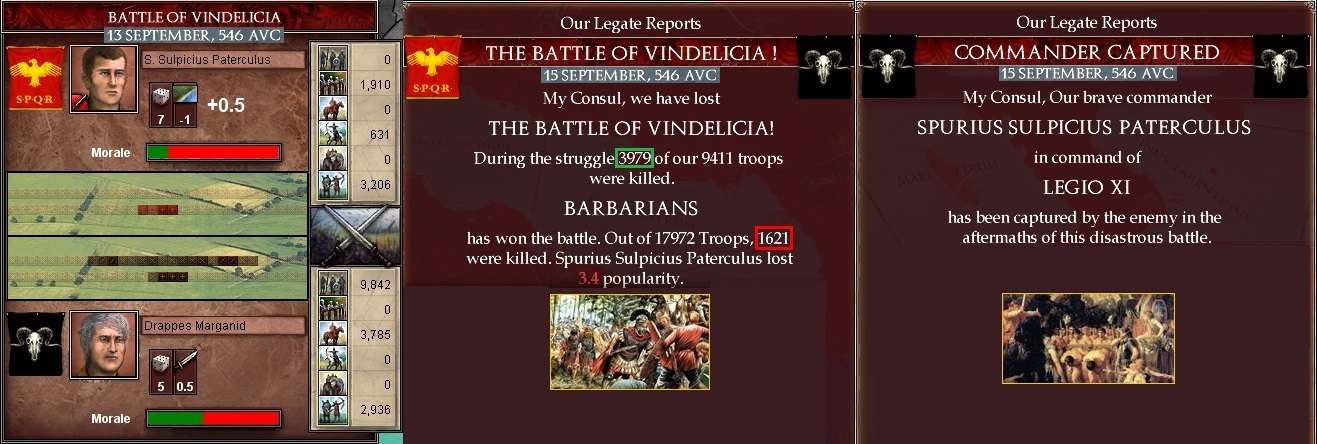

Legio XI had remained in Gallia Cisalpina as the re-established protection for northern Italia. And on 8 June, scouts reported a warband of 22,000 Hermunduri barbarians taking the well-trodden path from Marcomanni to Raetia, where they would arrive on 28 June.

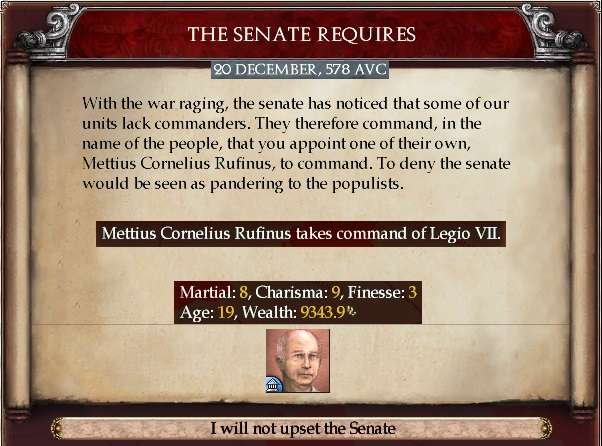

The Senate agreed Paterculus would need some reinforcements to help deal with an invasion of this size, authorising the recruitment of three new cohorts in northern Italia – all auxiliaries (manpower still being under pressure from the Great Eastern War). Two cohorts of principes and one of archers began training, at a total cost of almost 40 gold talents.

The barbarians assaulted Raetia’s stockade as soon as they arrived: it took until 6 July for them to be beaten back, with almost half the garrison lost, but at the cost of a good number of attackers and all of their morale. Legio XI should now have enough time to gather their reinforcements and attack before Raetia fell. Though care would need to be taken.

This was a heartening victory, but far to the east, another great battle was being fought. Its result may well decide the outcome of the Great Eastern War.

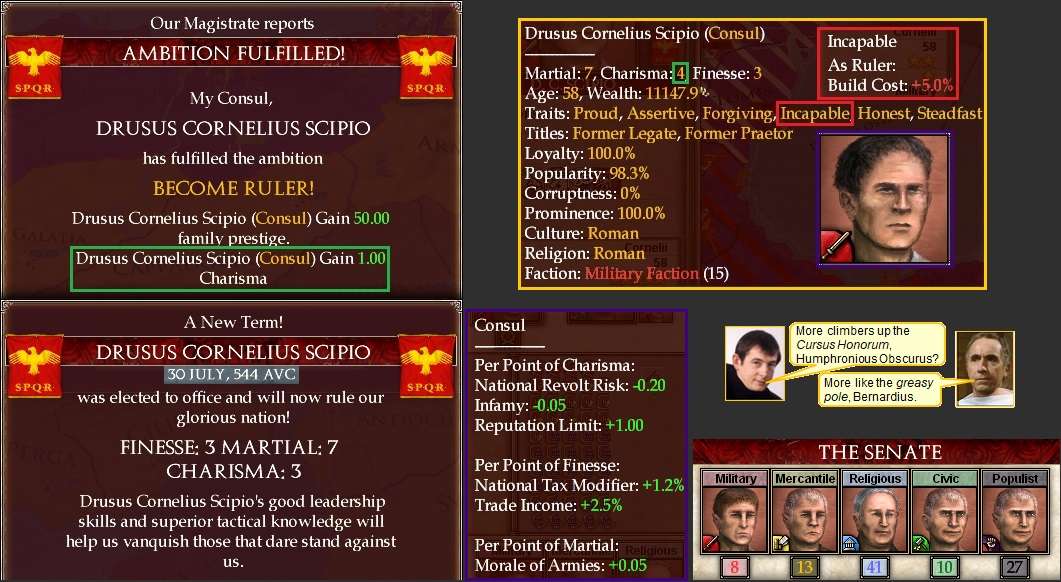

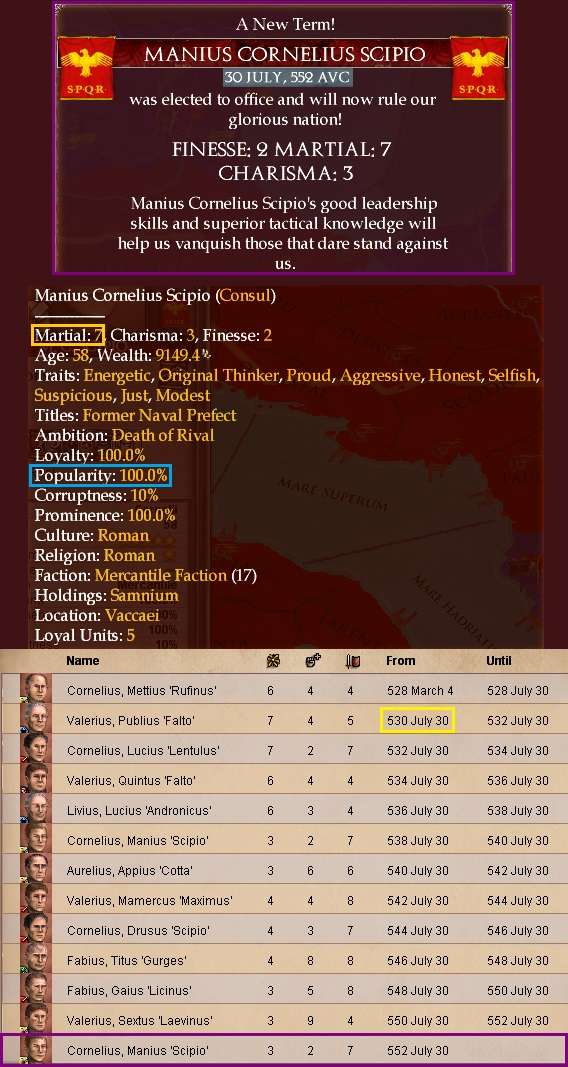

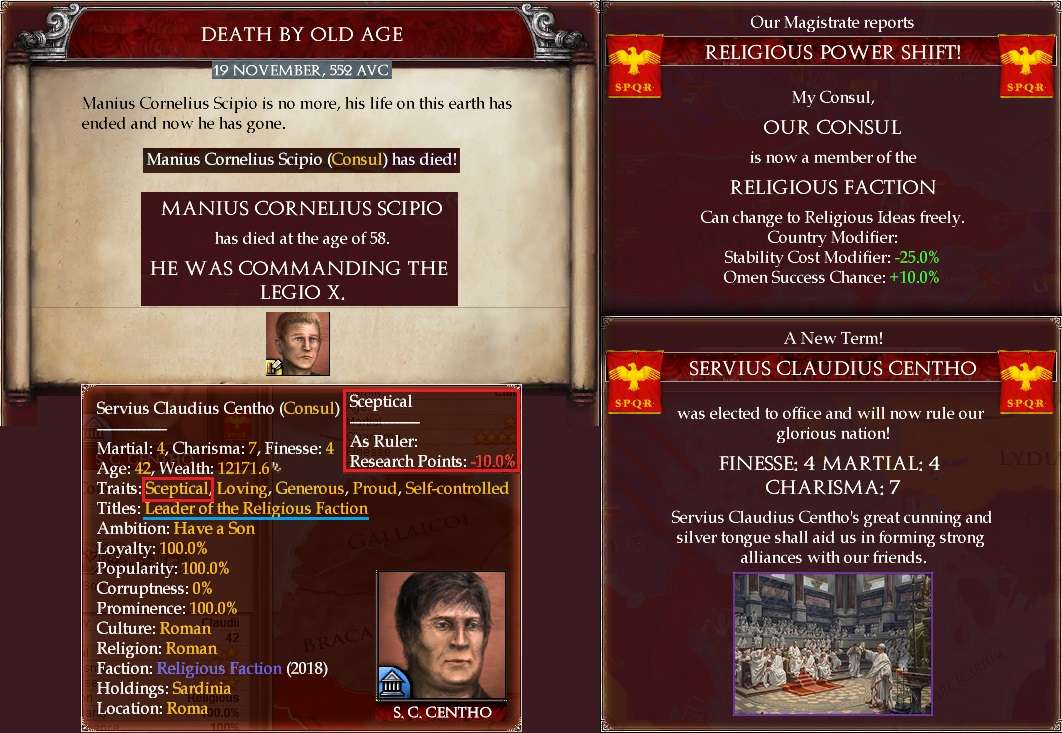

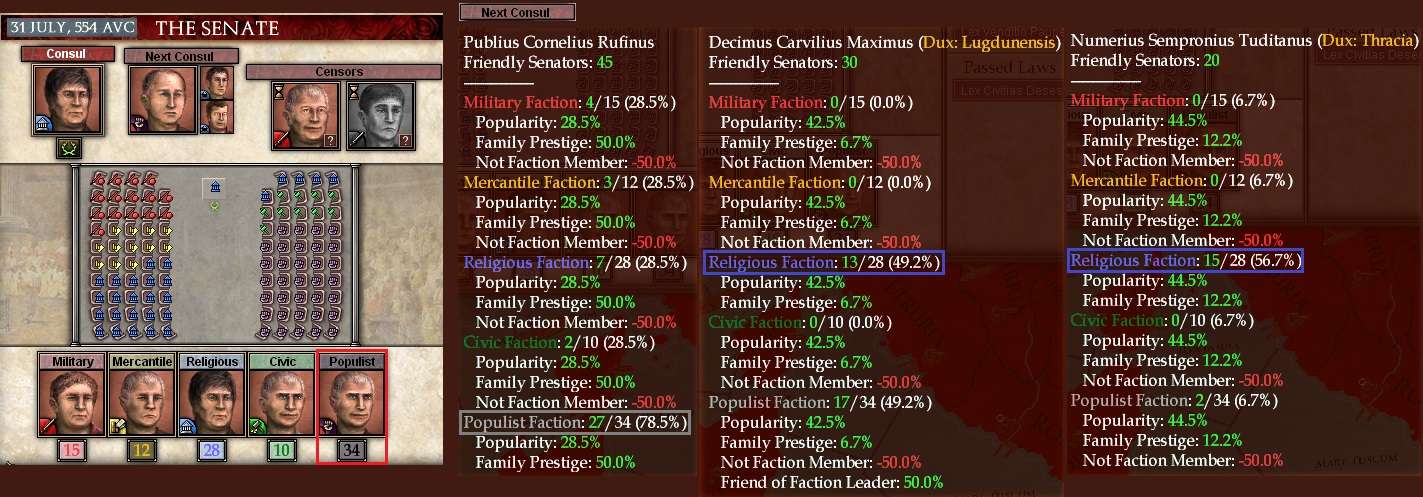

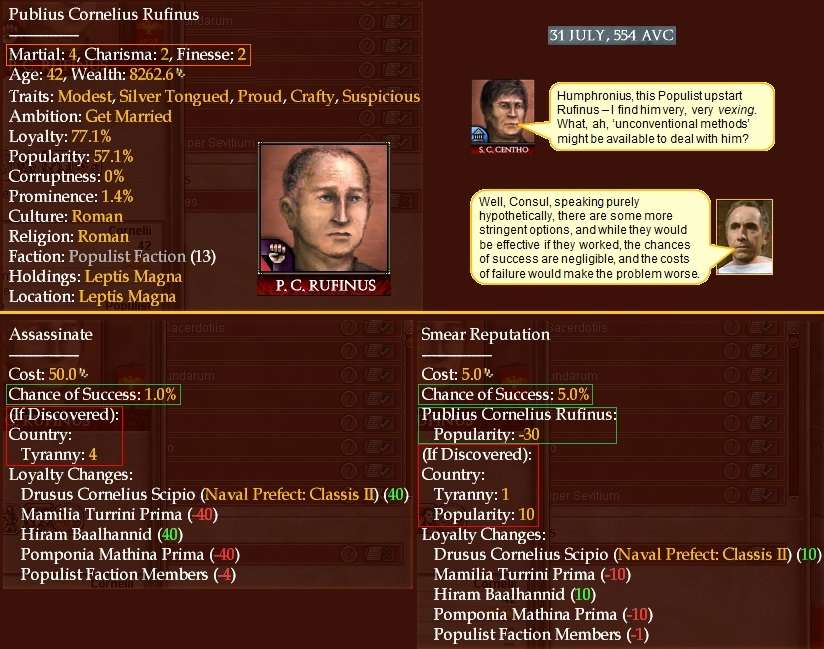

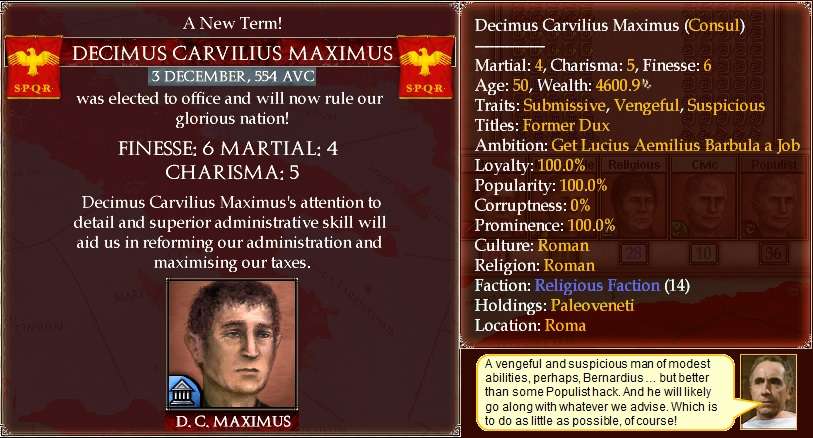

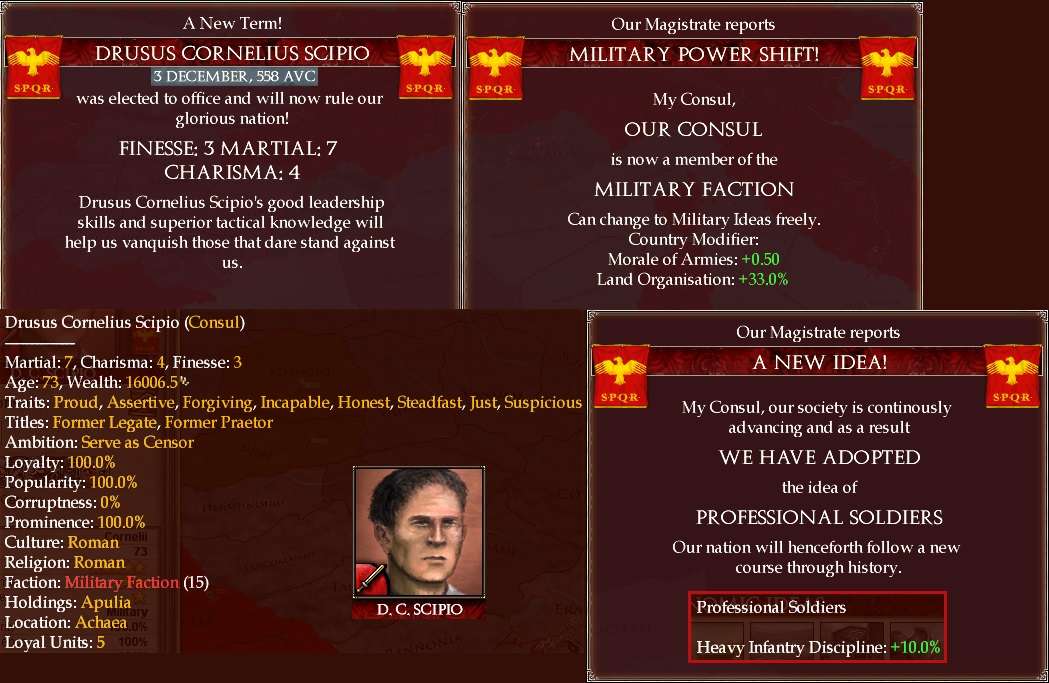

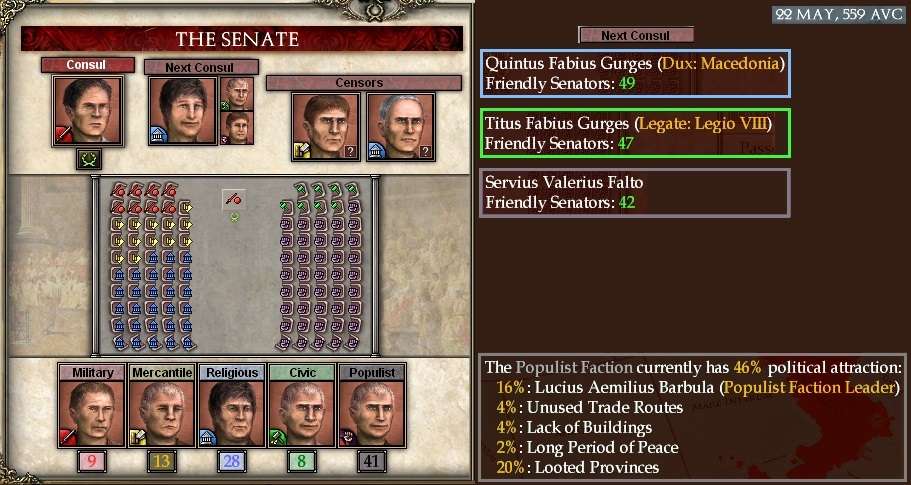

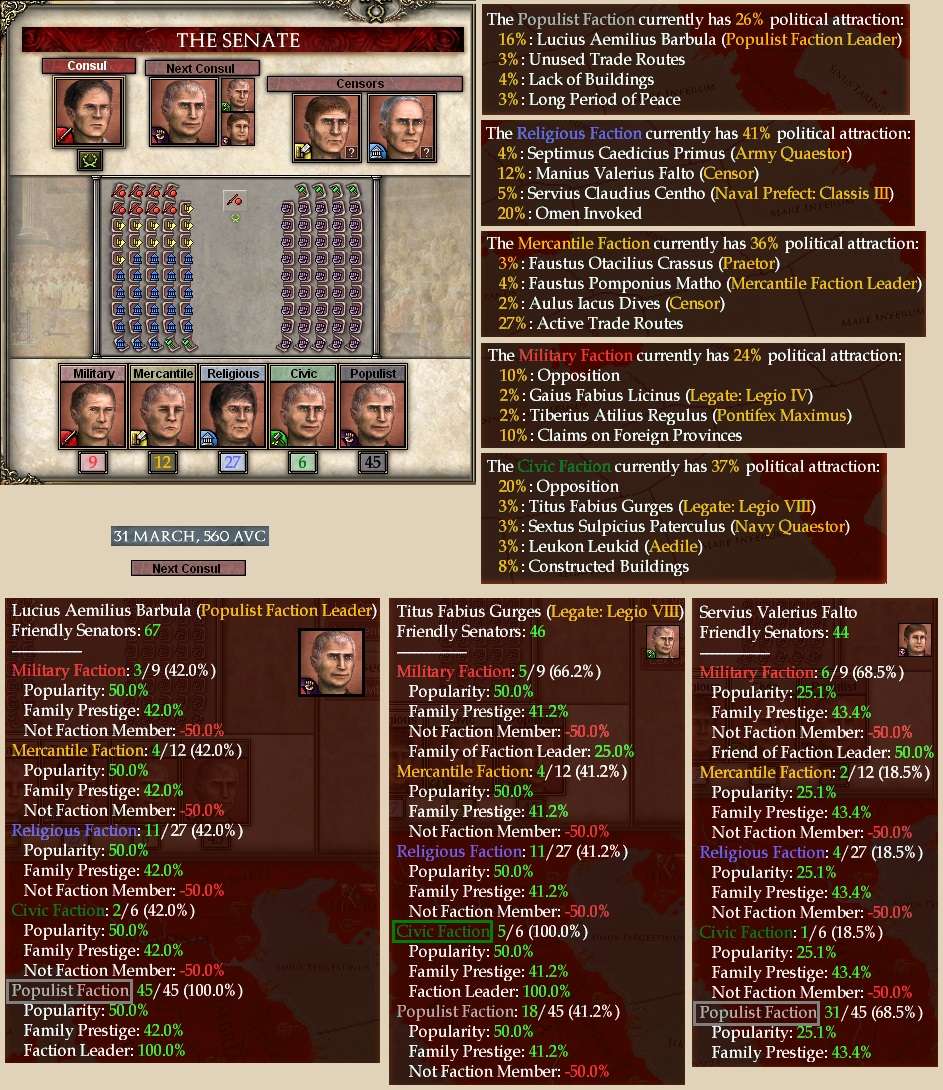

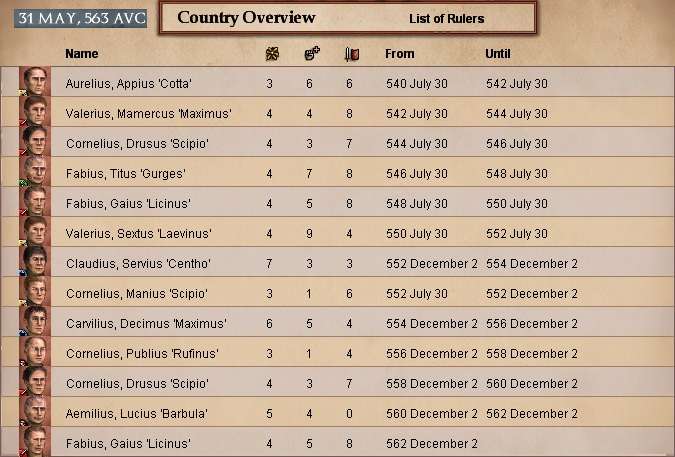

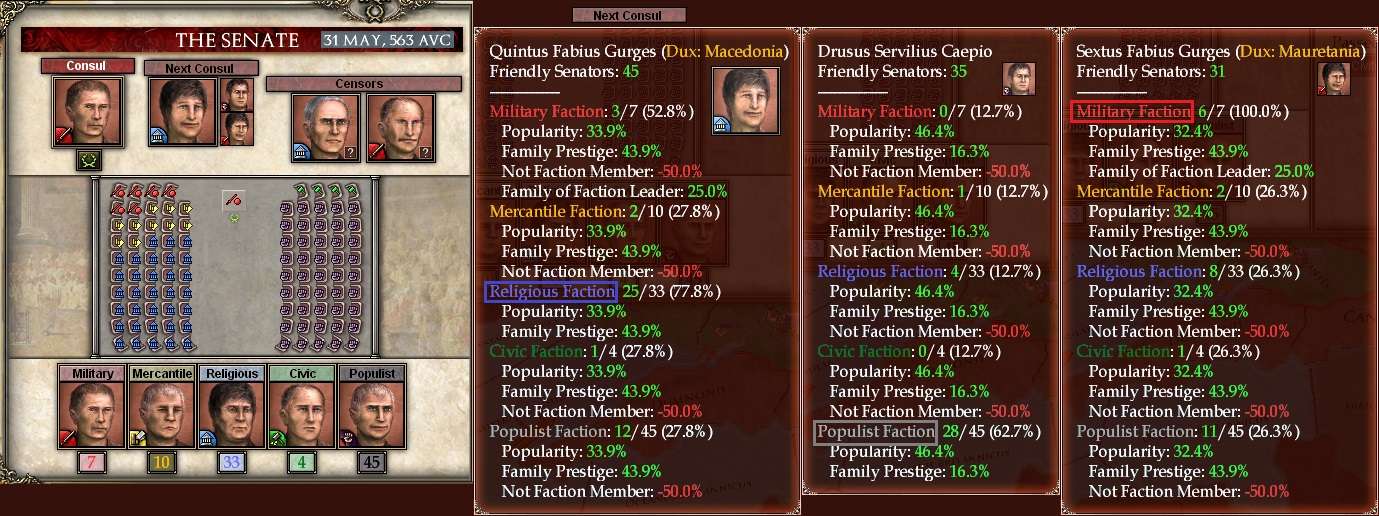

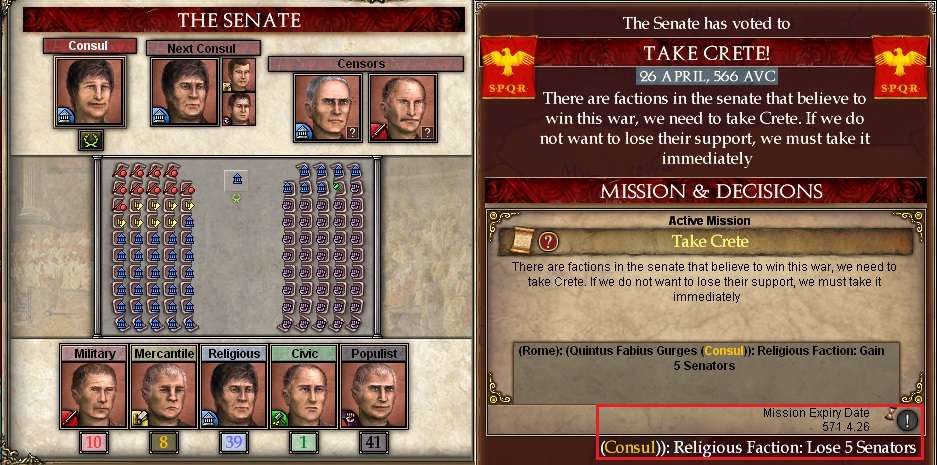

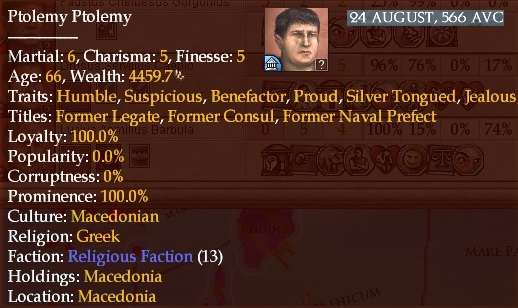

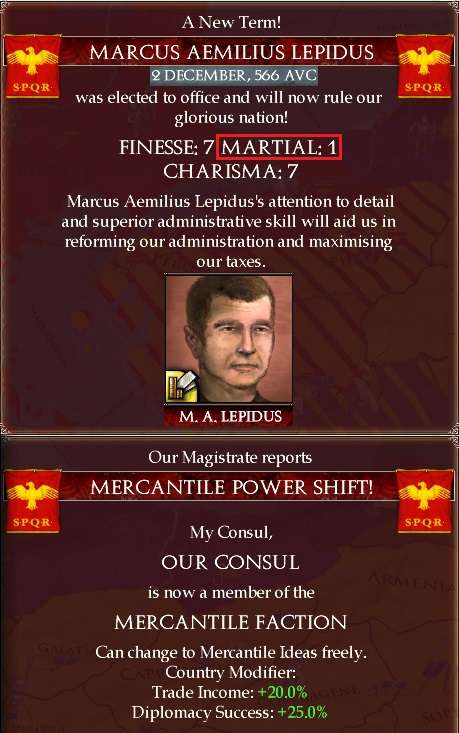

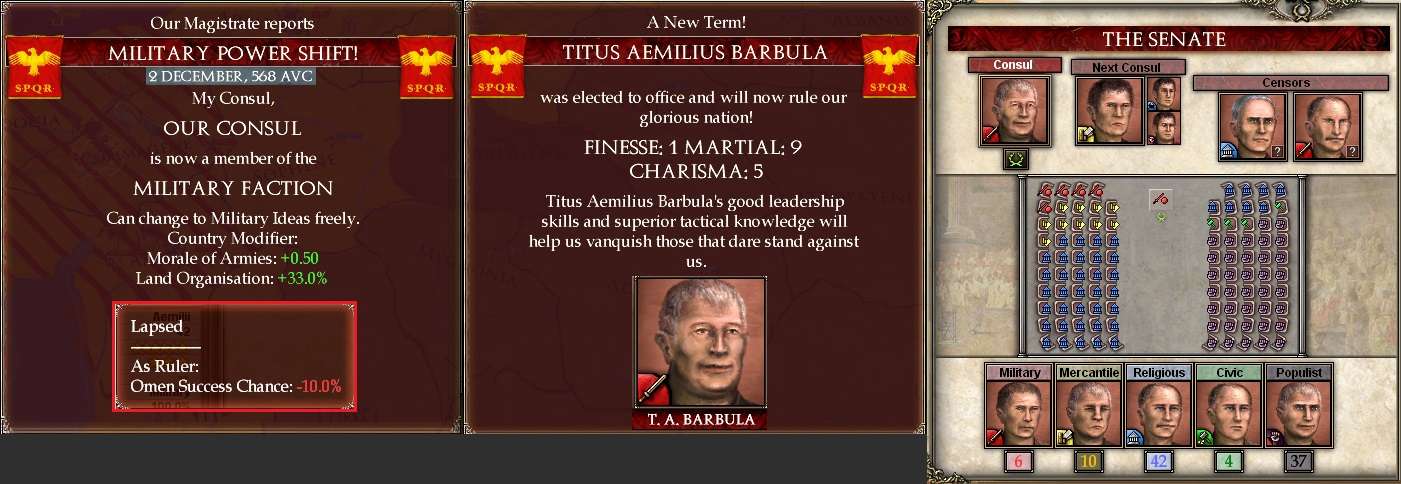

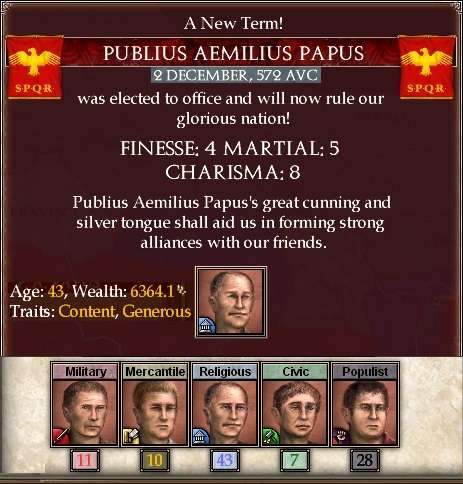

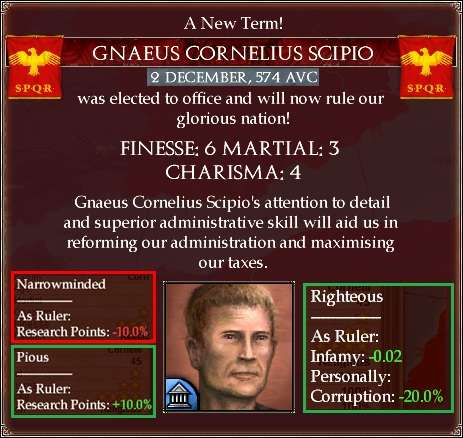

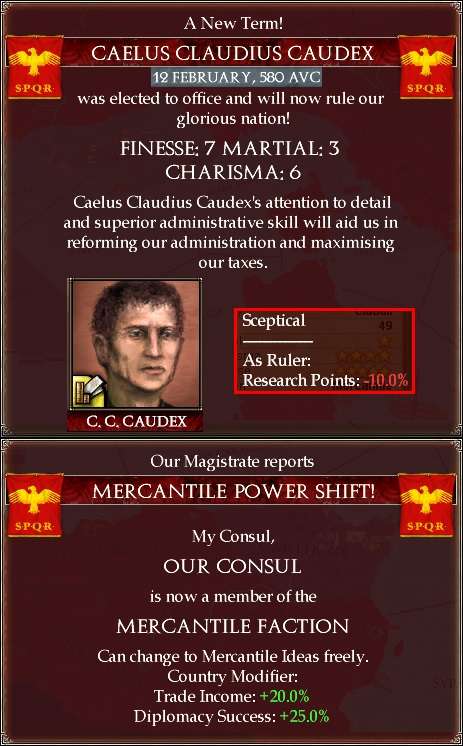

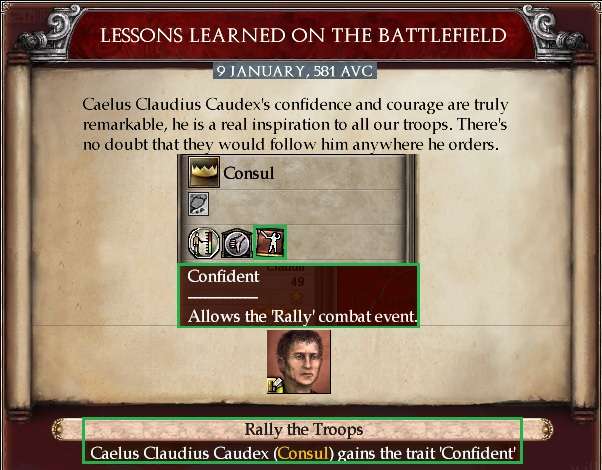

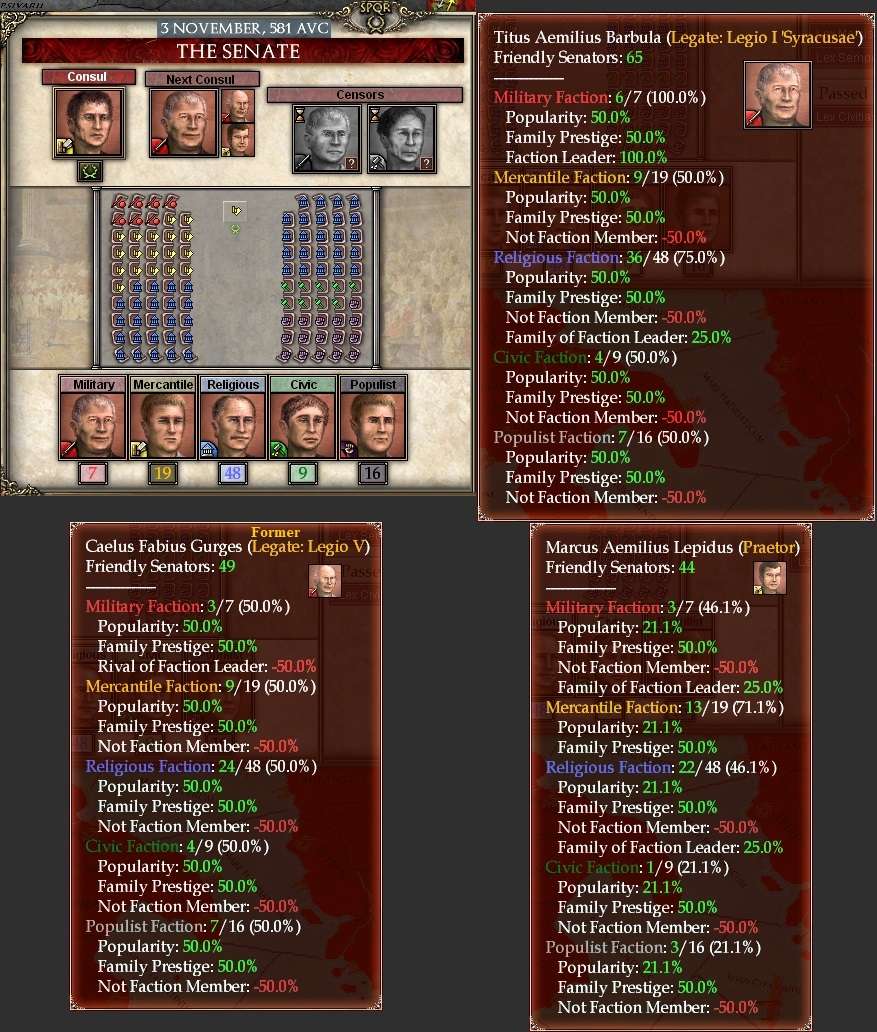

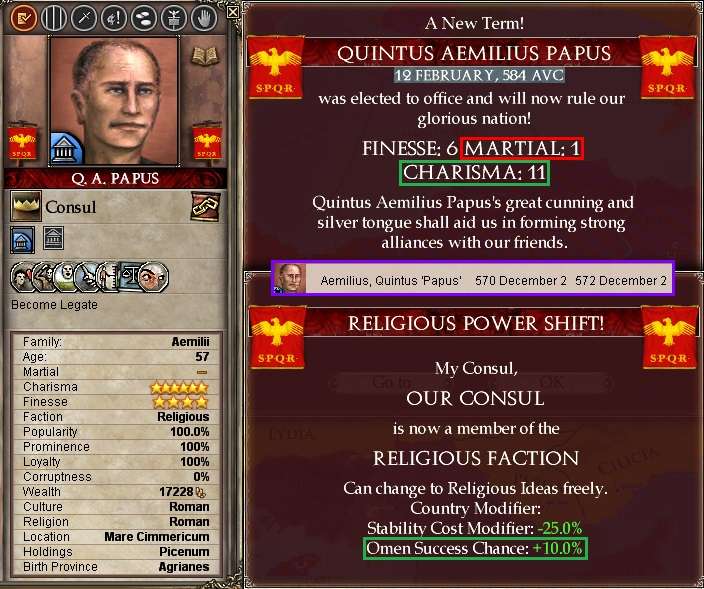

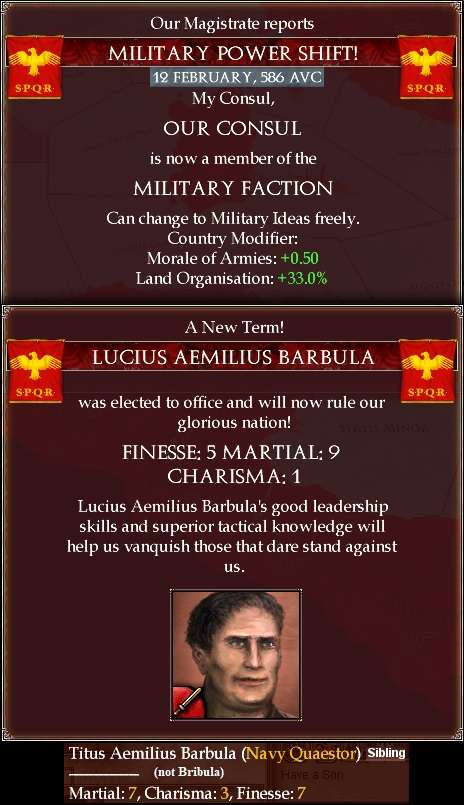

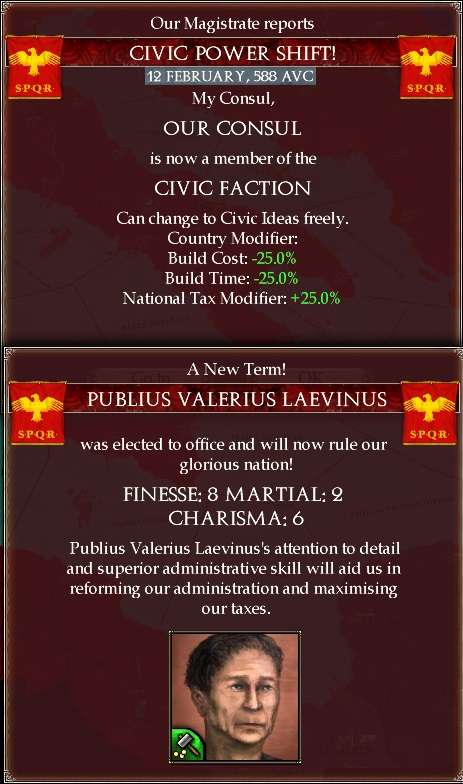

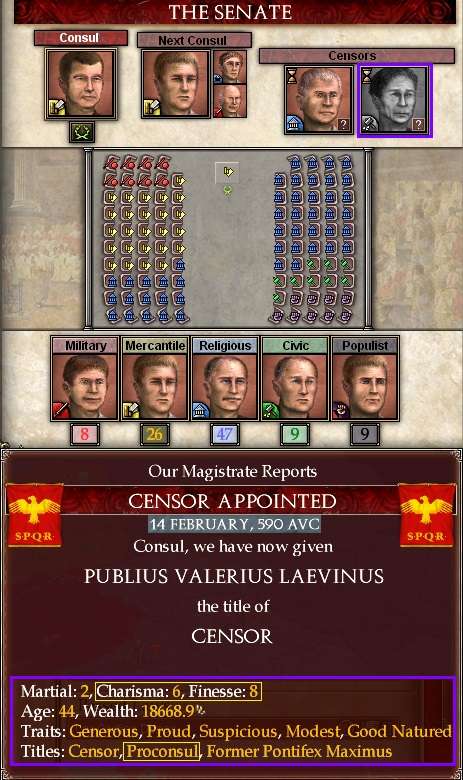

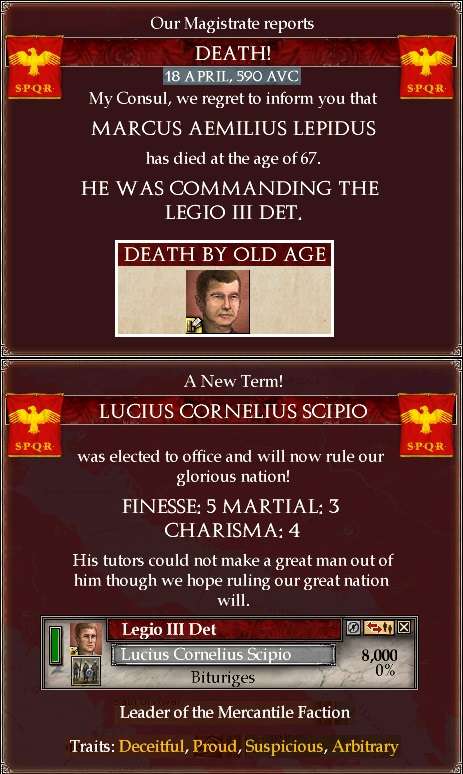

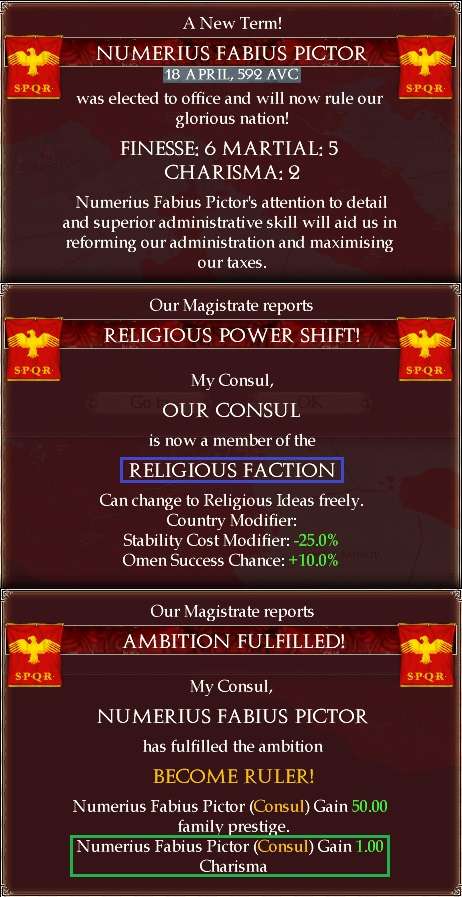

As at 8 July 544, In the lead-up to the next Consular election, the Religious faction still dominated the numbers in the Senate, but offered none of the three leading candidates. It was a fine balance between Civic, Military and Mercantile hopefuls.

§§§§§§§

2. Graecia and Pontus

2. Graecia and Pontus

January-April 543

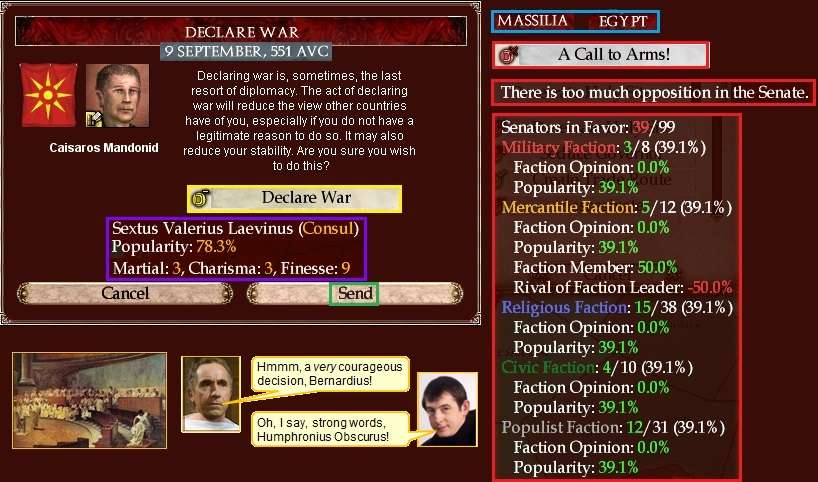

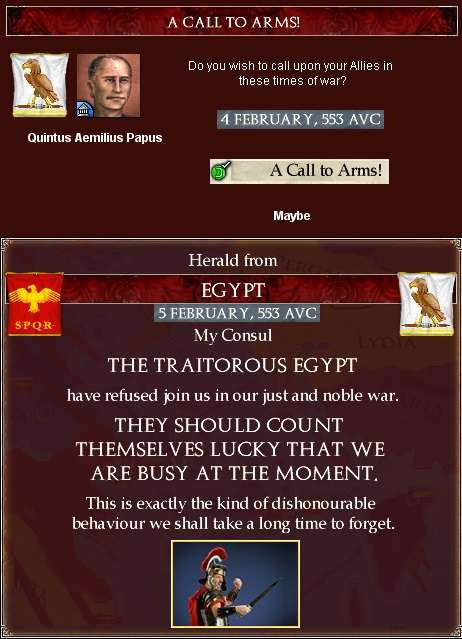

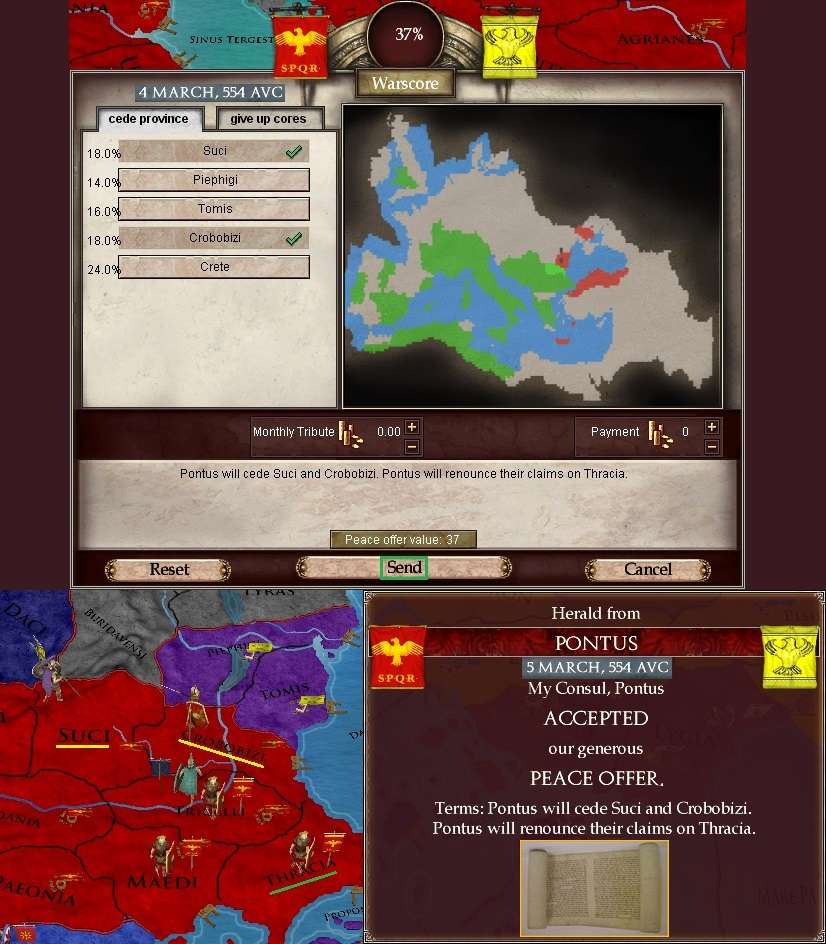

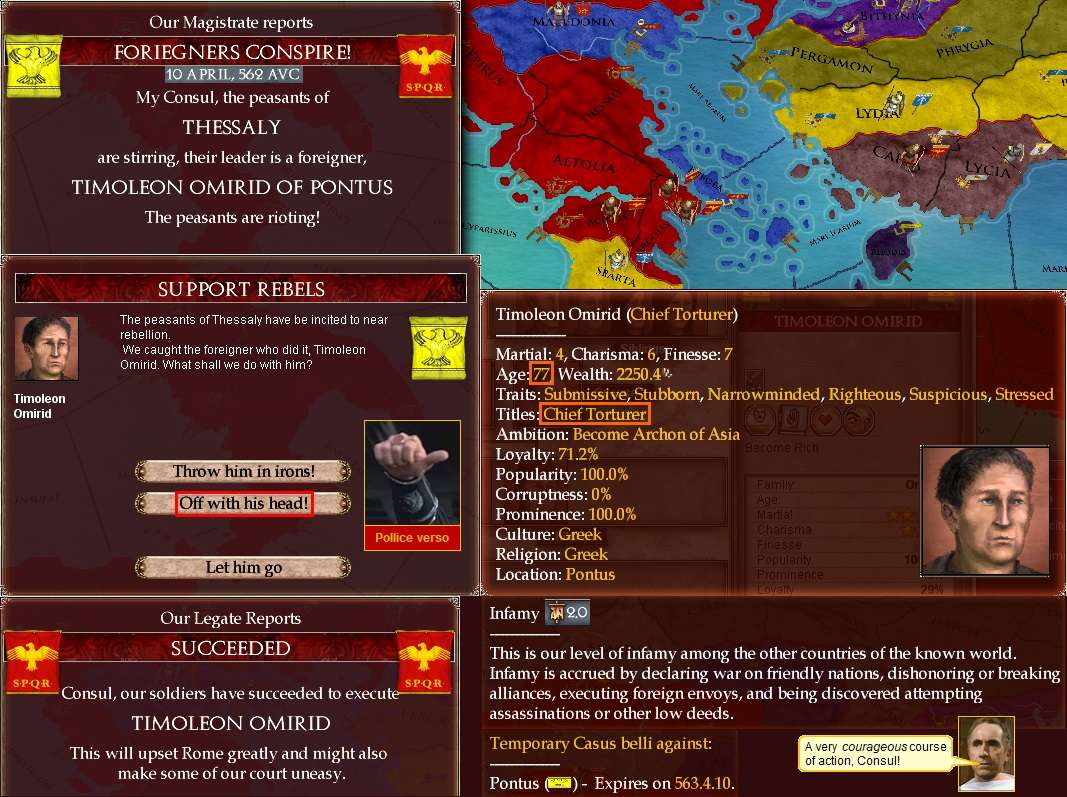

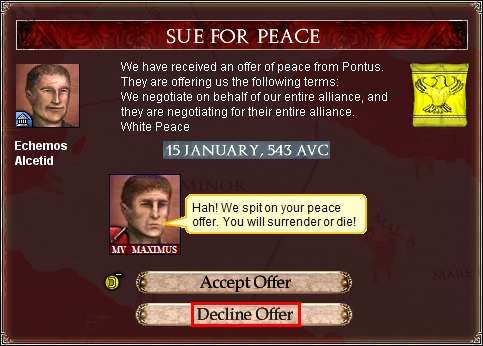

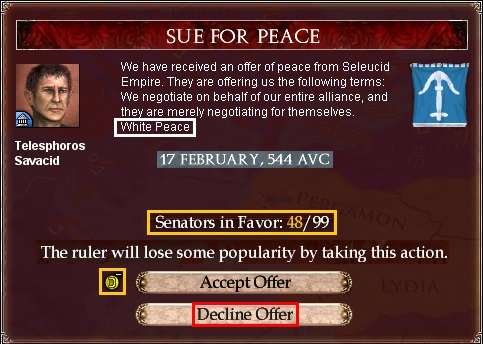

The first event of note for the new year in the East was a peace offer from Pontus. Despite their now poor position, they dared ask for a white peace. The Senate was opposed by a small margin. The Consul was far more dismissive. Pontus would be ground into the dust!

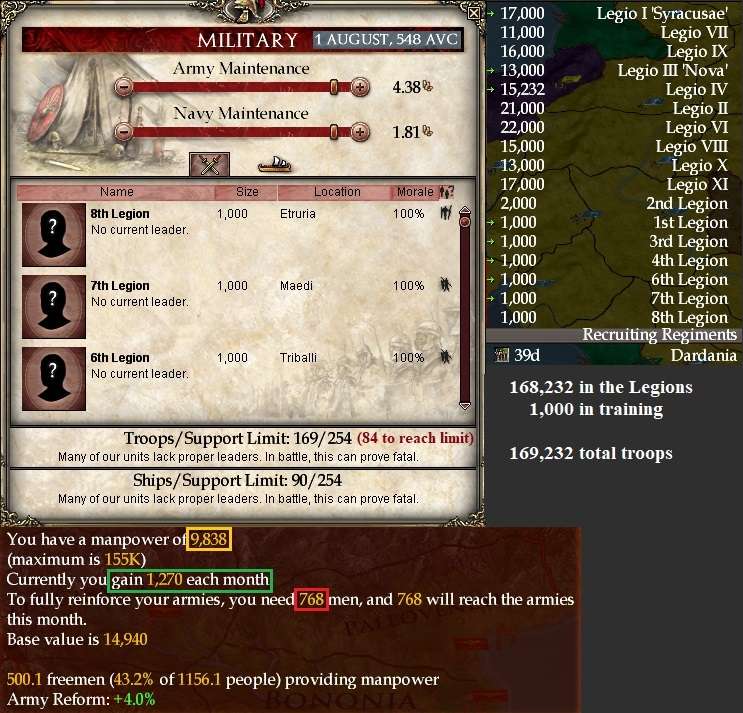

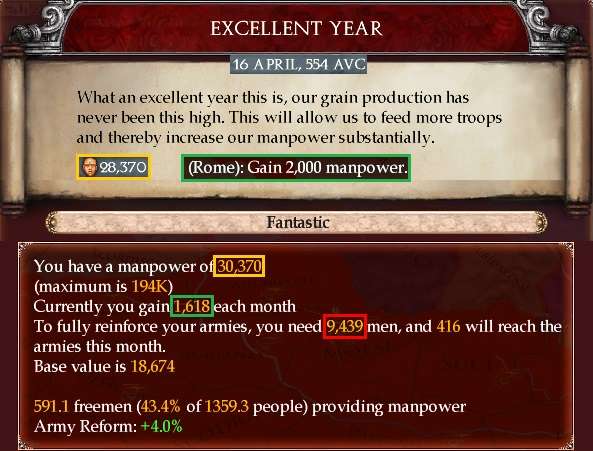

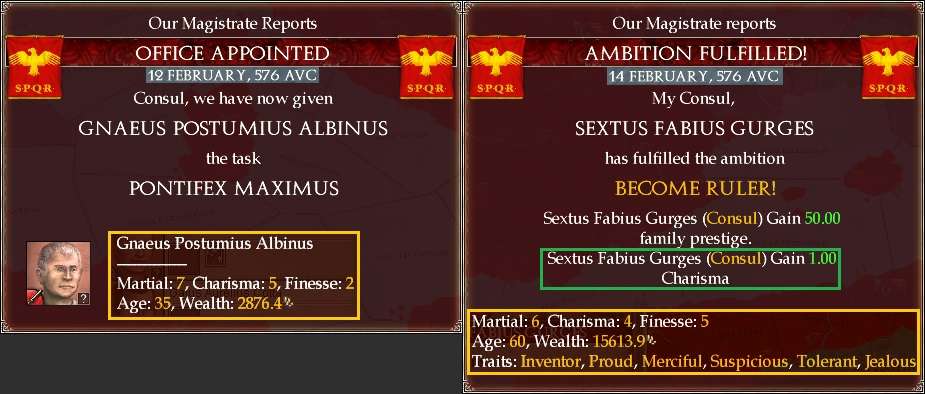

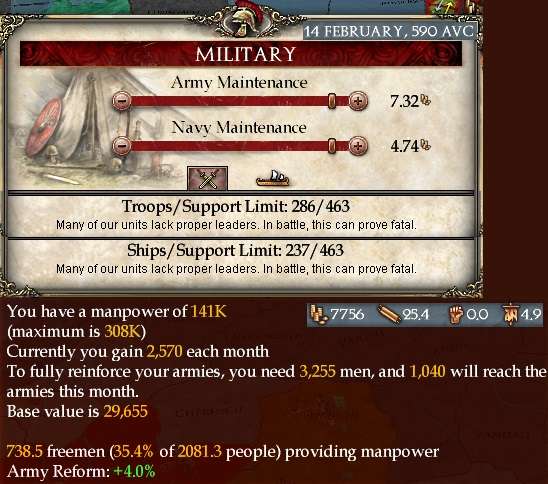

By early February 543, Roman manpower stood at 58,014, with 21,918 replacements needed for the army. As troops moved and sieges continued, news came on 12 March that Colchis had managed to take back Phasis, one of their old provinces that also bordered eastern Pontus, from the Seleucids. Impressed by this, Rome sought a military access agreement with Colchis, but it was rejected. A pity.

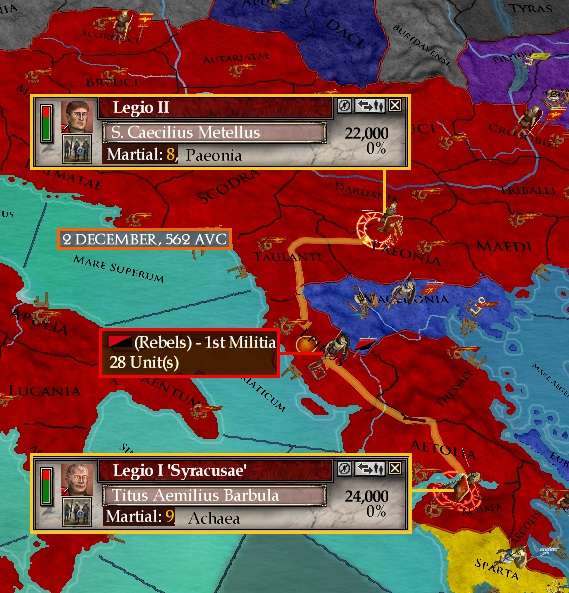

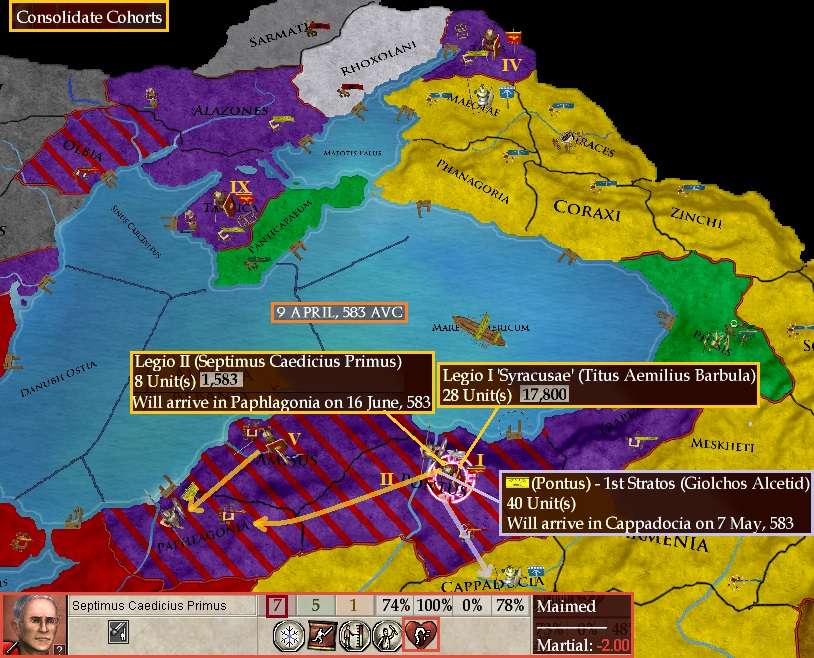

Legio I (23,600 men in 32 cohorts) began marching on Maezaei on 21 March, timed to arrive there a little after the colony was founded on 16 April. This would also place Caudex next to an army of Pontic holdouts camped in barbarian Scordisci, to its north-east.

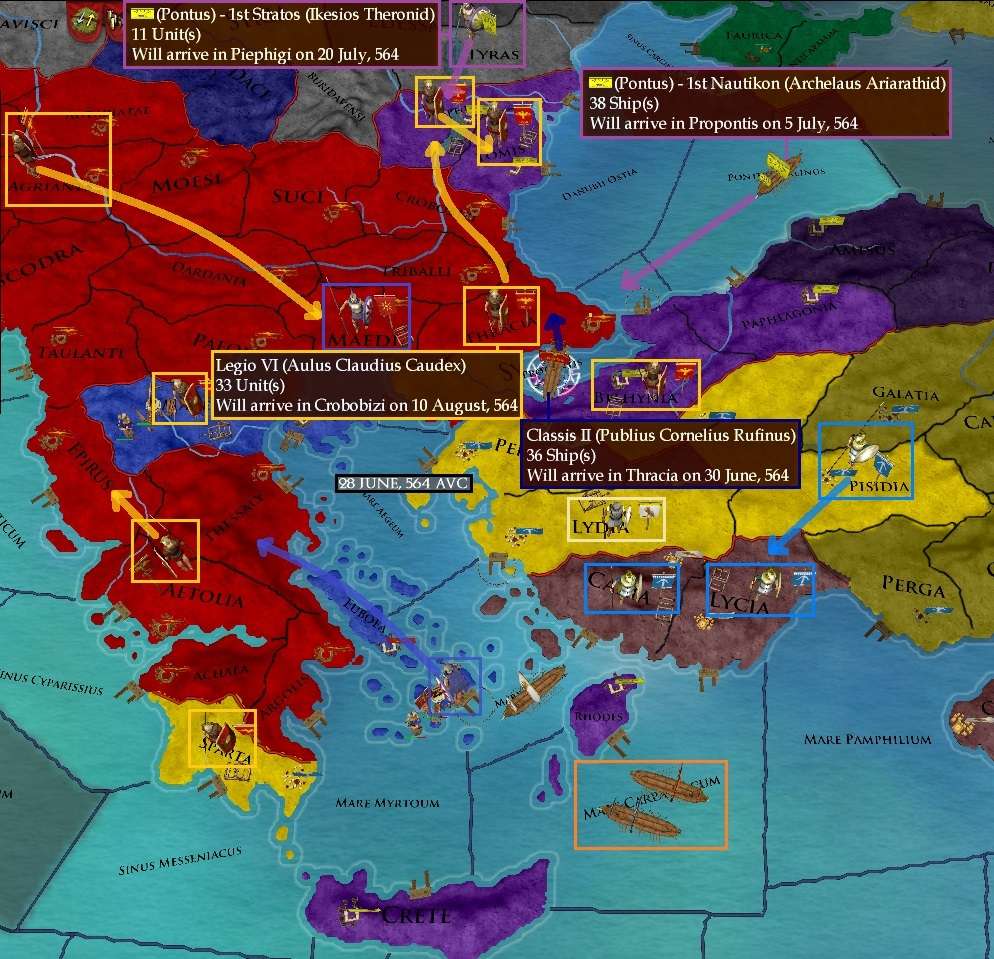

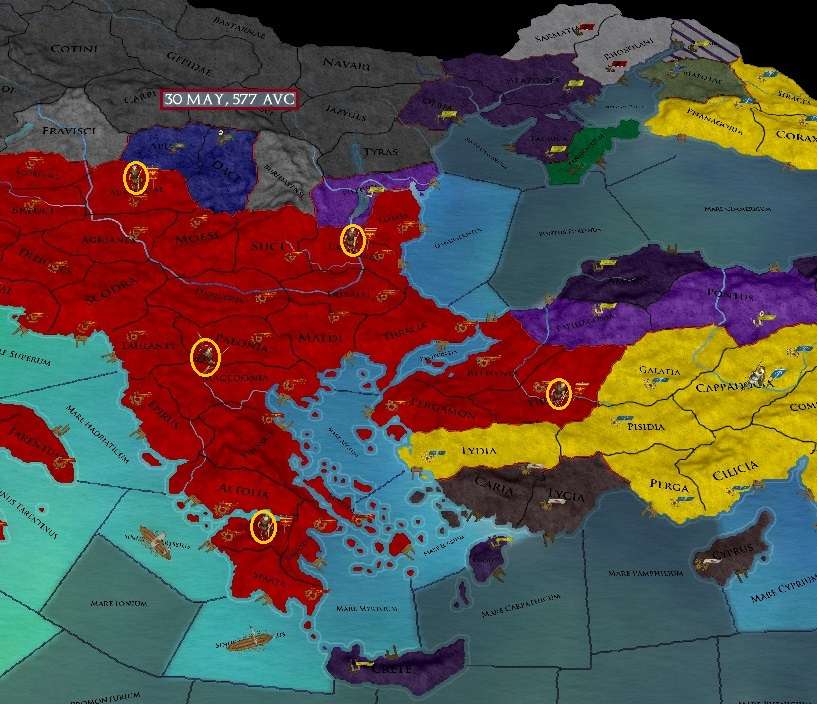

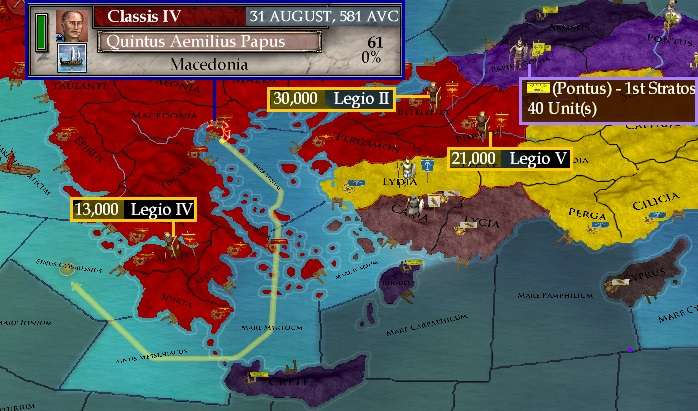

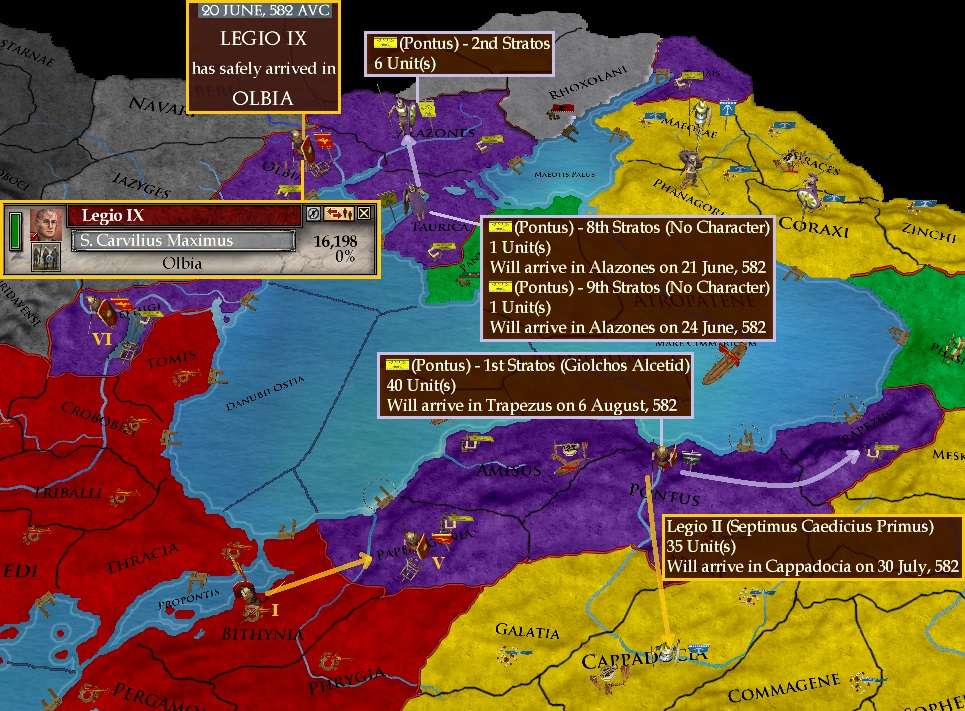

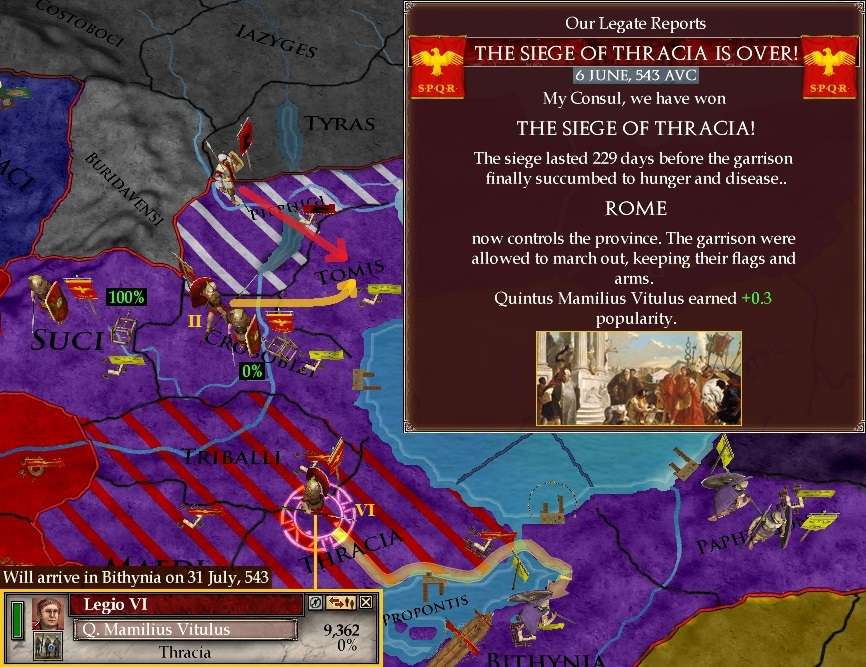

Legio IV (17,900 men), its work done in Moesi, was sent to Thracia four days later. Licinus’ mission would be to take the war against Pontus into Asia Minor, while smaller detachments maintained their sieges throughout Thrace [Note: Here, as before, I use ‘Thrace’ to describe the whole region, and ‘Thracia’ the specific province].

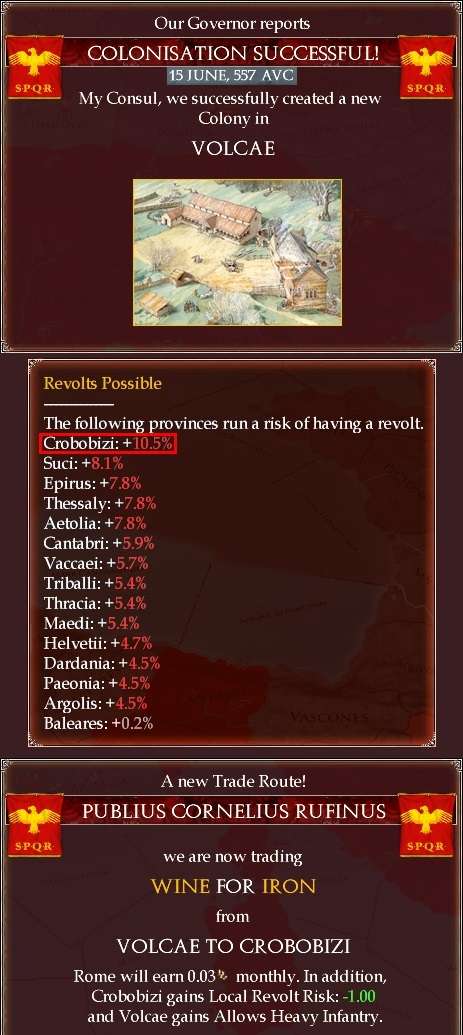

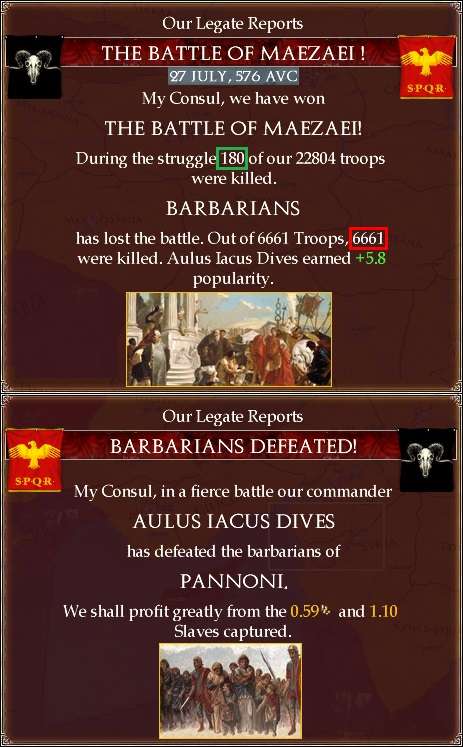

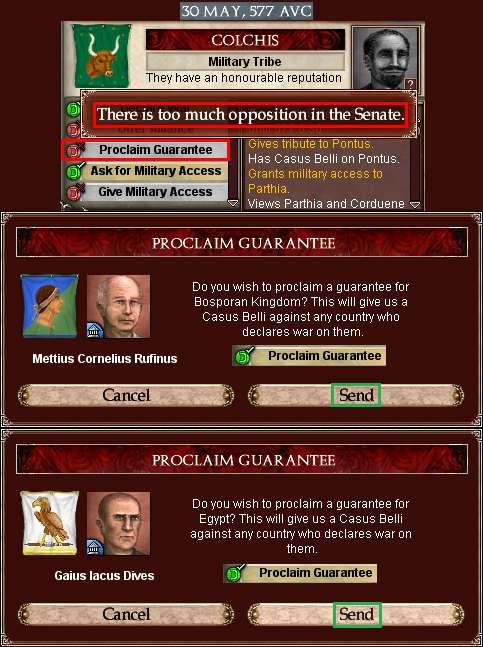

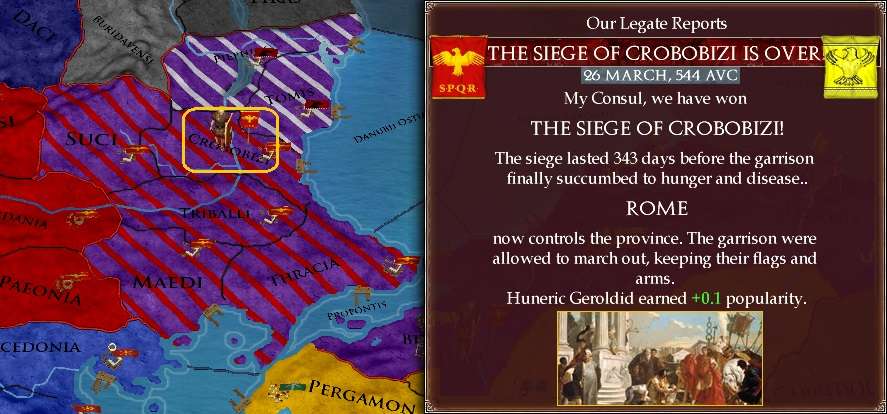

On 21 April, Legio V arrived in Crobobizi to begin a siege there and Legio I arrived in the newly colonised Maezaei. Caudex immediately began marching on Scordisci, determined to remove any Pontic threat lurking behind Roman lines while they simultaneously took the war to the Pontic heartland.

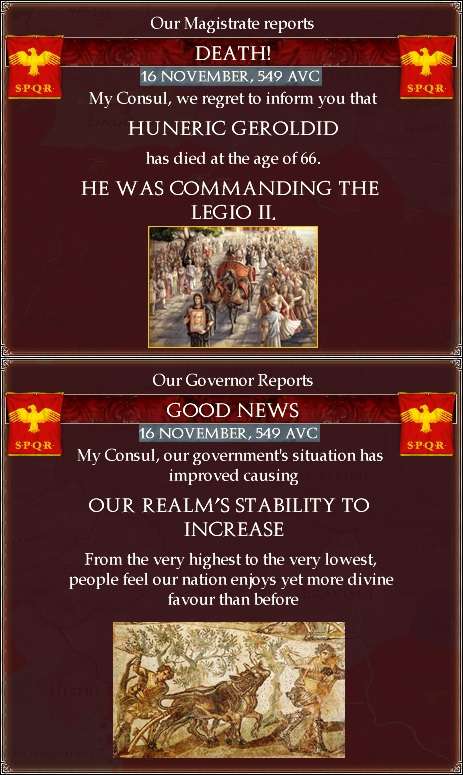

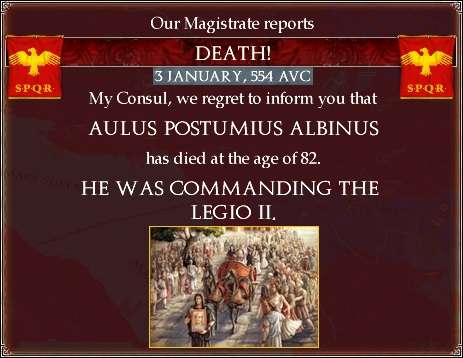

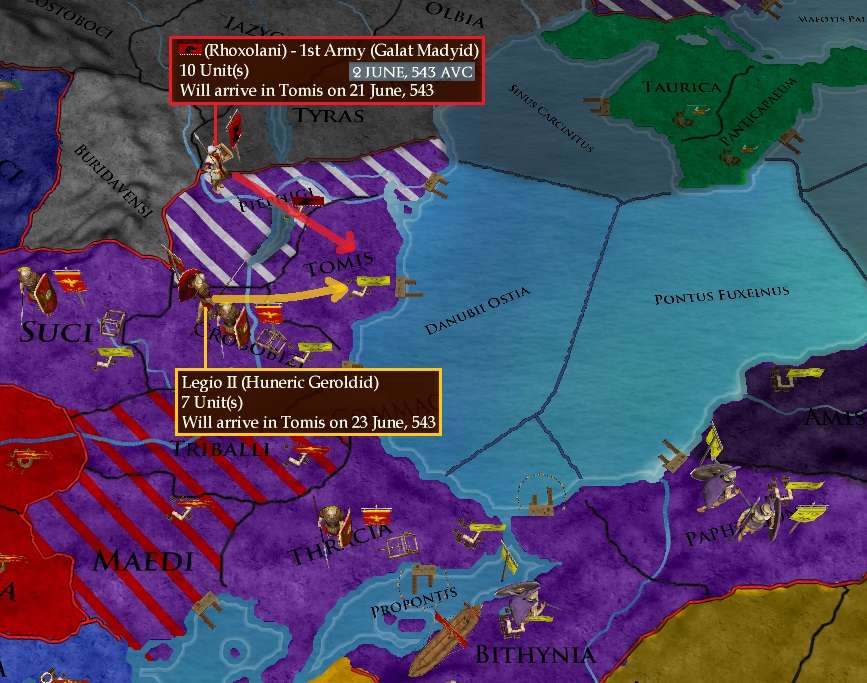

Just a day later, Triballi fell to Huneric Geroldid, who marched his (small) Legio II towards Tomis via Crobobizi.

§§§§§§§

May-July 543

It took until 23 May for Legio XI to arrive in Breuci, where their numbers were enough to be sustained by the countryside. In Scordisci, the Pontic army was trying to escape north to Eravisci as Caudex bore down on them. They would not be quick enough: Caudex [Martial 9] (15,172 men) caught the Pontic 3rd Stratos under Pausanias Zagreid [Martial 7] on 27 May. The Pontic army escaped as soon as it could, after losing 789 of its 4,338 men; Caudex – his judgement of the task vindicated – lost just 216.

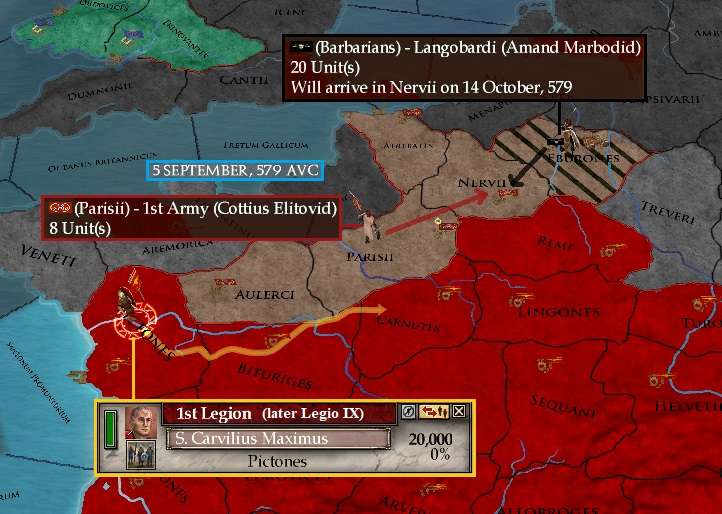

With the victory in Scordisci on 31 May, Legio I set off in pursuit of P. Zafreid to Eravisci, while Paterculus was sent over to face the barbarian threat that had emerged earlier that month in Raetia (as described in Section 1).

On 2 June Rhoxolani finished its siege of Piephigi: which was all right, but not their subsequent advance on Tomis, which they were due to reach just two days before Legio II was due to get there. Geroldid continued in the hoped something might delay them.

More fruitfully, Caudex ran down P. Zagreid’s 3rd Stratos in Eravisci on 28 June, winning another four-day victory, losing 406 of his almost 15,000 men, while killing 1,743 of the 3,149 Pontic defenders. Attacking over a river had made the battle a little more expensive than it might have been.

After the battle finished on 2 July, Zagreid fled even further north into the barbarian lands of Cotini. Caudex called off the pursuit, considering the Pontic army a spent force and not wanting to sustain even more attrition than he was at the moment. He headed south-east, back to nearby Roman Autariatae.

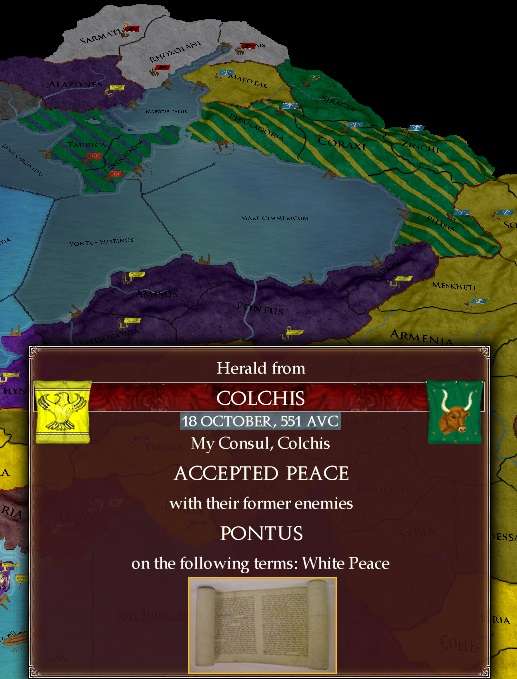

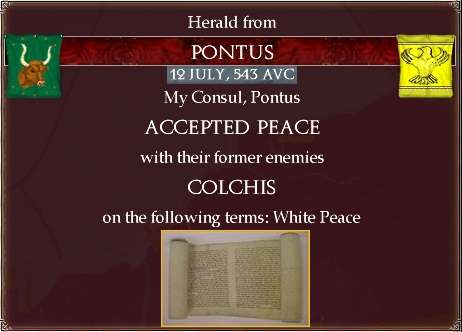

A herald, coming from Pontus under ‘diplomatic immunity’, announced on 12 July that they had made peace with Colchis. It would have no effect on Roman plans.

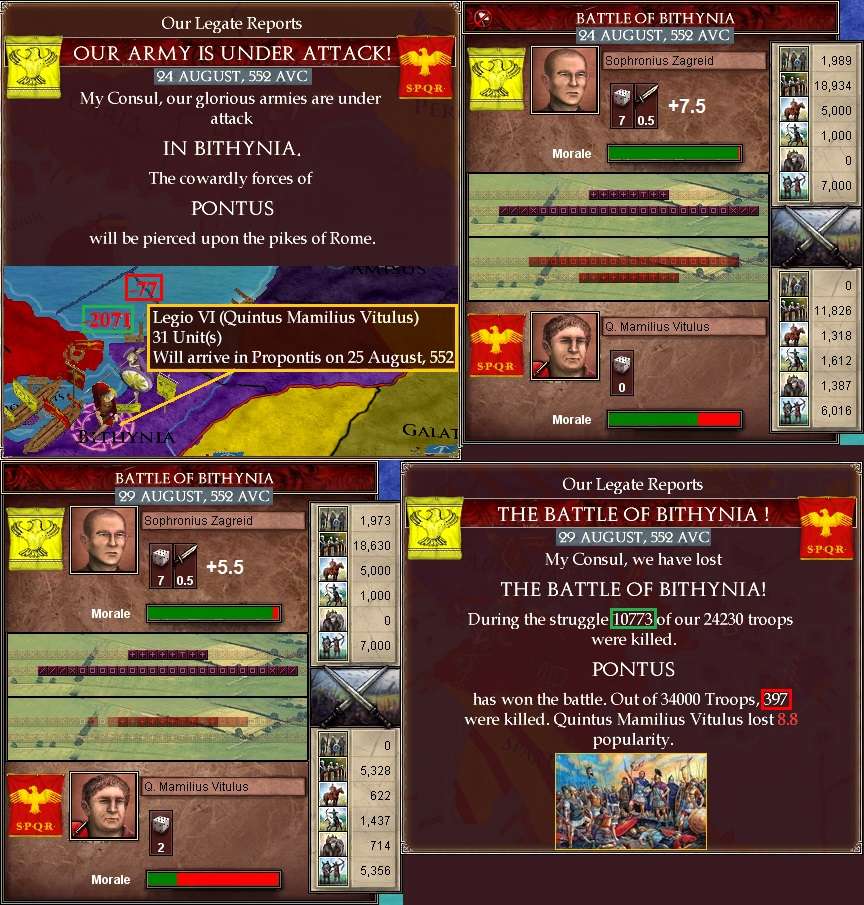

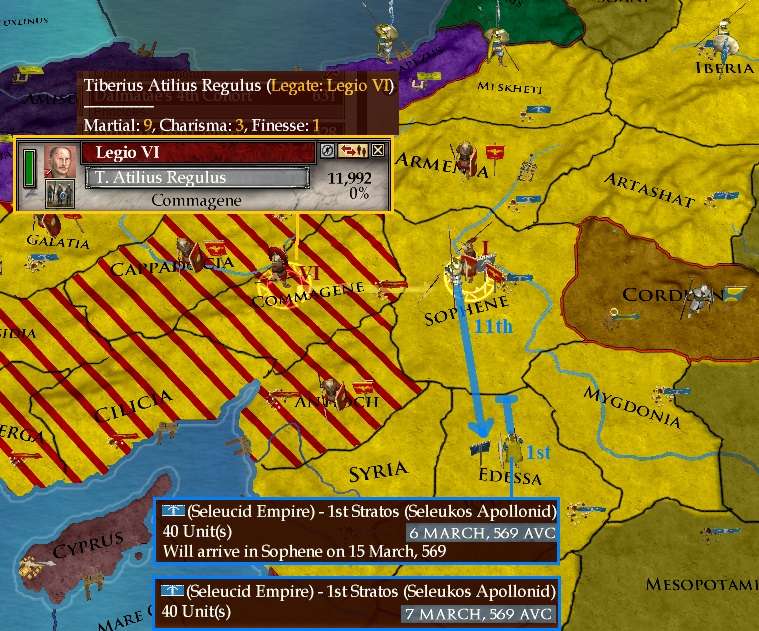

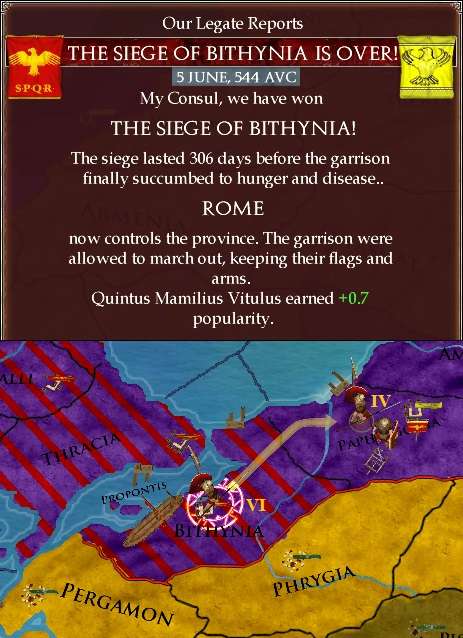

A single Pontic regiment was encountered in Bithynia when Legio VI arrived on 31 July: they were all put to the sword for the loss of 23 of Vitulus’ 9,400 legionaries by 2 August, when he set up his siege camp. Legio IV (21 cohorts) was in Thracia by then and due to arrive in Bithynia on 24 September.

§§§§§§§

August-December 543

Breuci was added to Rome’s burgeoning Illyrian holdings on 15 August, with the obligatory stockade construction starting as soon as the colonists were settled.

And another recruit slaughter occurred in Bithynia on 25 August, one thousand trainees despatched for the loss of 22 men from Legio VI.

It was noticed on 27 August that Macedon had managed to assemble an army of 18 regiments (strength unknown) to challenge the 13 regiments of rebels still besieging Epirus. This time, the Macedonians would win and avert the shame of having one of their remaining provinces fall to the rebel rabble.

The key city of Suci fell to Rome on 29 August after a full year of siege: Legio VIII was now free to join the other Roman units marching to Bithynia.

Licinus arrived in Bithynia with Legio IV (around 17,600 men by then, and suffering 5% attrition) on 25 September and headed straight for Paphlagonia, where only three Pontic regiments had gathered. It would take until 31 October to reach it and set begin a siege, by which time all the Pontic units had headed further east. But its 2,000 man garrison would surely take many months to reduce.

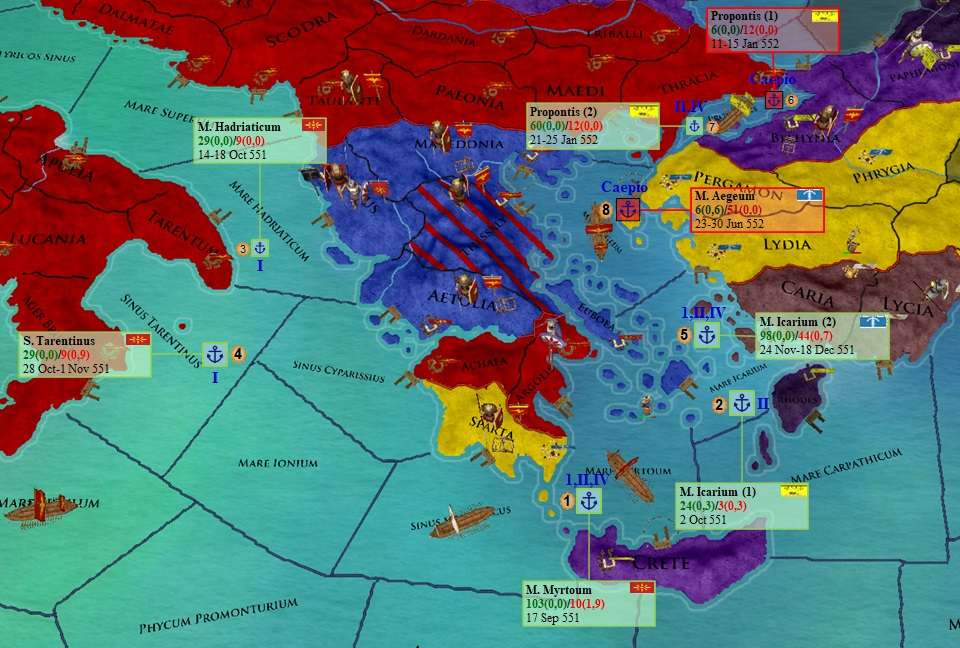

November passed, and by 26 December Rhoxolani had succeeded in taking Tomis, while Legio VIII made it to Bithynia, marching then to Paphlagonia, where they would relieve Legio IV of siege duties, allowing Licinus to continue into the Pontic heartland.

§§§§§§§

January-March 544

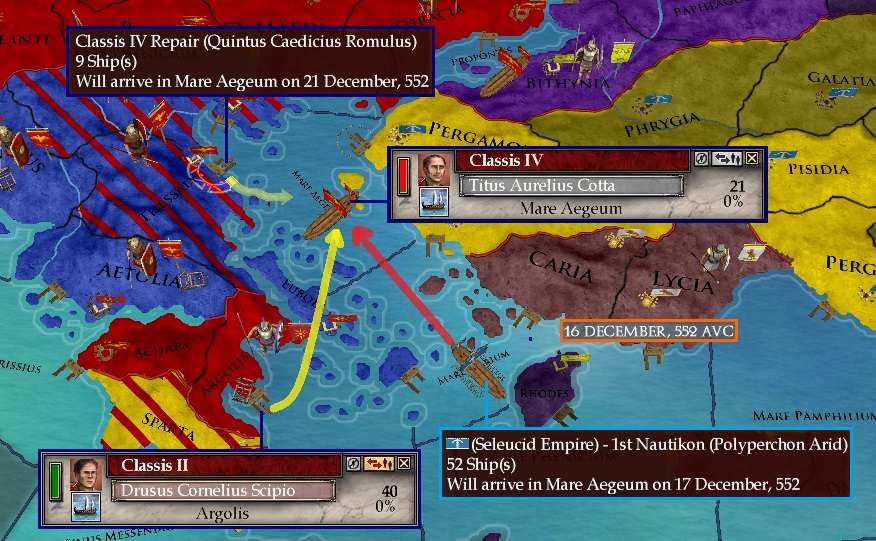

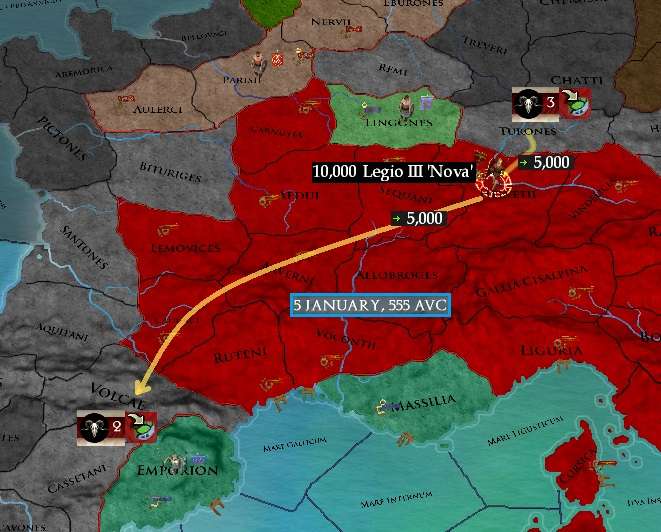

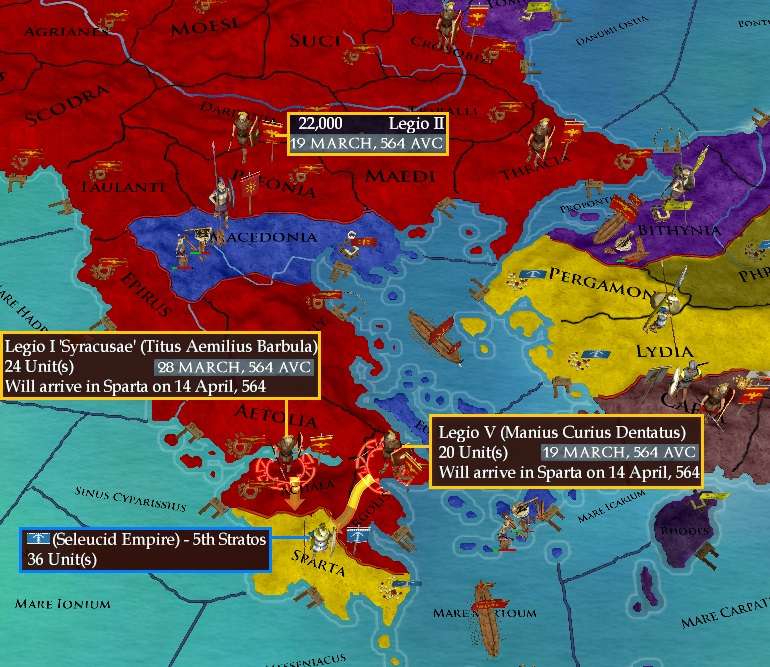

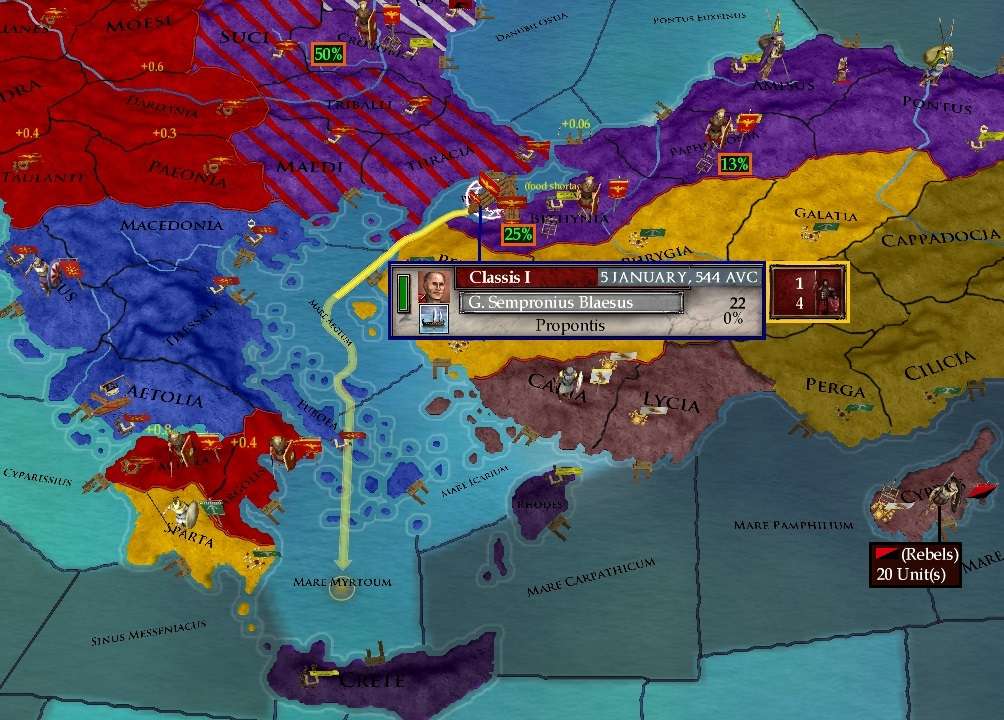

On 5 January, Classis I took a reduced (to avoid seaborne attrition) Legio VIII on board: they would head to Crete and attempt a naval landing, which they hoped would be unopposed.

Another small detachment (3,000 men under M.C. Dentatus – not a populist) was embarked from Argolis on 8 February. Their target was Rhodes, which Rome had already verified was unoccupied. They were besieging the Pontic island’s fortress by 27 February.

Back in Illyria, Caudex had been on guard duty in Breuci, his 16 cohorts now recovered to full strength after a long rest. A report on 14 February of a small barbarian force (7,000 Insubres warriors) arriving in the Dacian province of Apuli was enough to have Legio I on the march: Moesi would be spared another ravaging this time, Caudex swore!

Also on 14 February, a small Roman naval detachment (four ships, no commander) that had been left in the Propontis was attacked by eight Pontic vessels under Orestes Pytheid. They escaped by 20 February, damaged but losing no ships to capture or sinking. Pytheid would soon get a nasty surprise: an Egyptian fleet of 97 ships was by then approaching from the south and due to arrive in the Propontis eight days later! But as cover, Classis IV (12 ships, T.A. Cotta) was despatched from its base in Achaea on 17 February to Mare Aegeum to provide a stronger presence while Classis I was off supporting the operations on Crete and Rhodes.

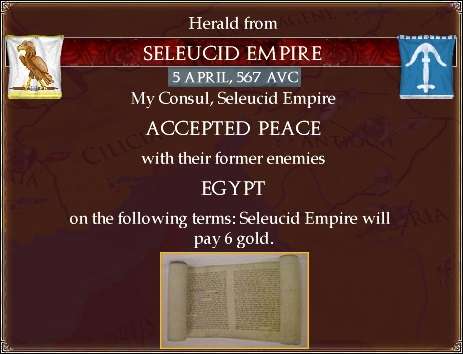

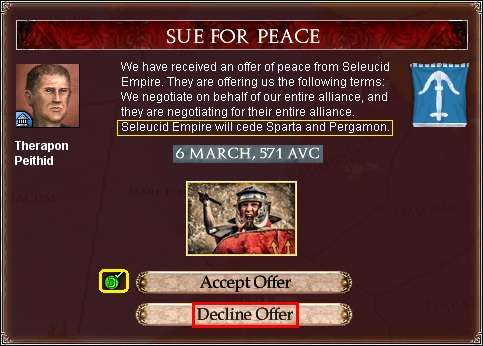

A Seleucid emissary with instructions to negotiate a white peace was received by Rome on 17 February.

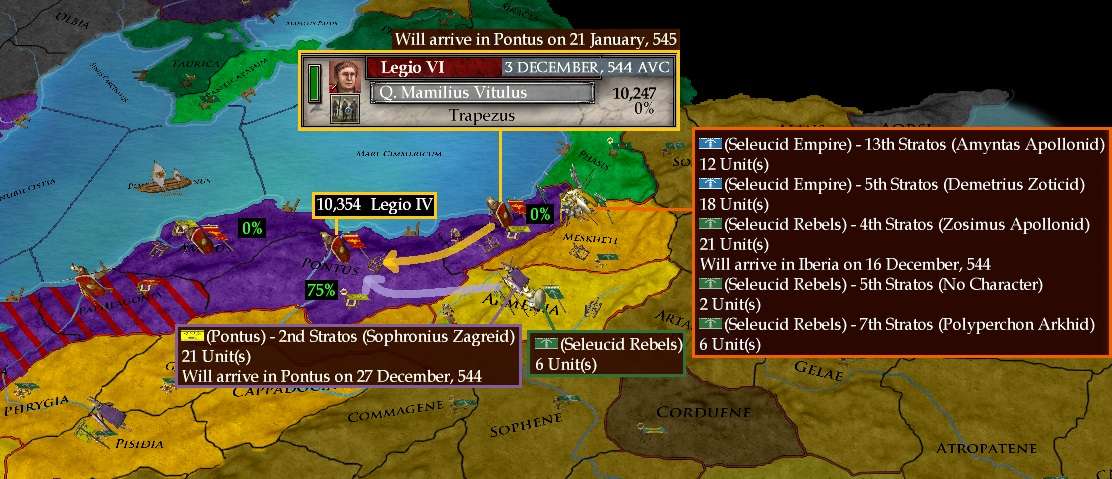

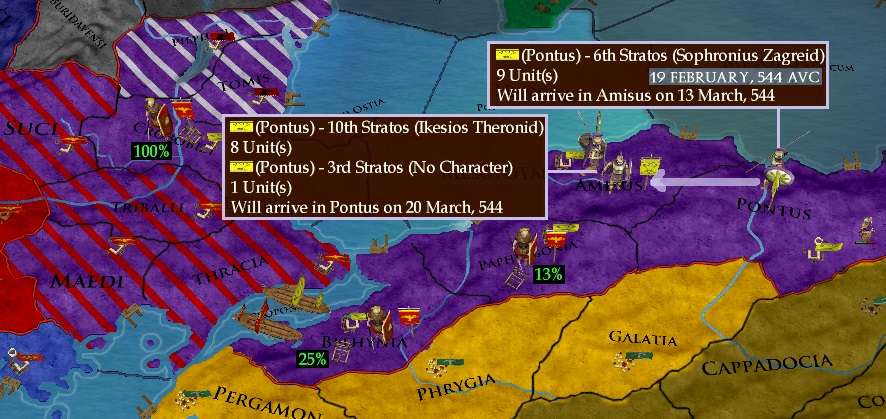

Two days later, Licinus had reports from spies in Pontus that the old enemy was beginning to assemble a credible force to the east in Amisus – commanded by the formidable Sophronius Zagreid. This would bear watching.

§§§§§§§

April-June 544

Caudex attacked the Insubres in Apuli on 12 April. It seems they had unwisely tried to assault the Dacians’ walls and their morale remained low when they were surprised by Rome’s premier general, leading a full-strength veteran 16-cohort legion. But there was a nasty surprise awaiting Caudex: the barbarian leader Orgetorix Vodenosid was a military prodigy of equal skill [Martial 9]. And he got the jump on Caudex for the first five days of the battle [Rome 0 v 7 Barbarian], before Caudex recovered somewhat [Rome 2 v 3 Barbarian]. Caudex won on 20 May, but had lost 504 men doing it, with the Insubres losing 673 of their 6,034 warriors before retreating north. Caudex was certainly reminded he was but mortal that day!

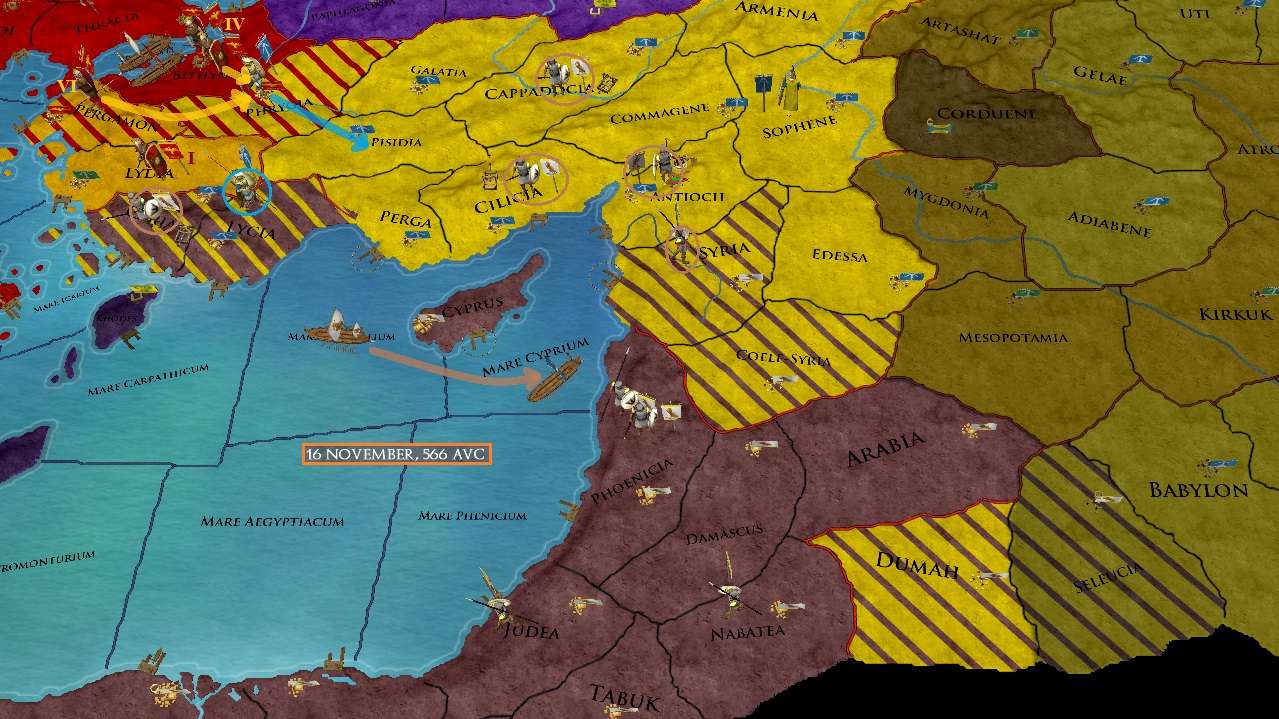

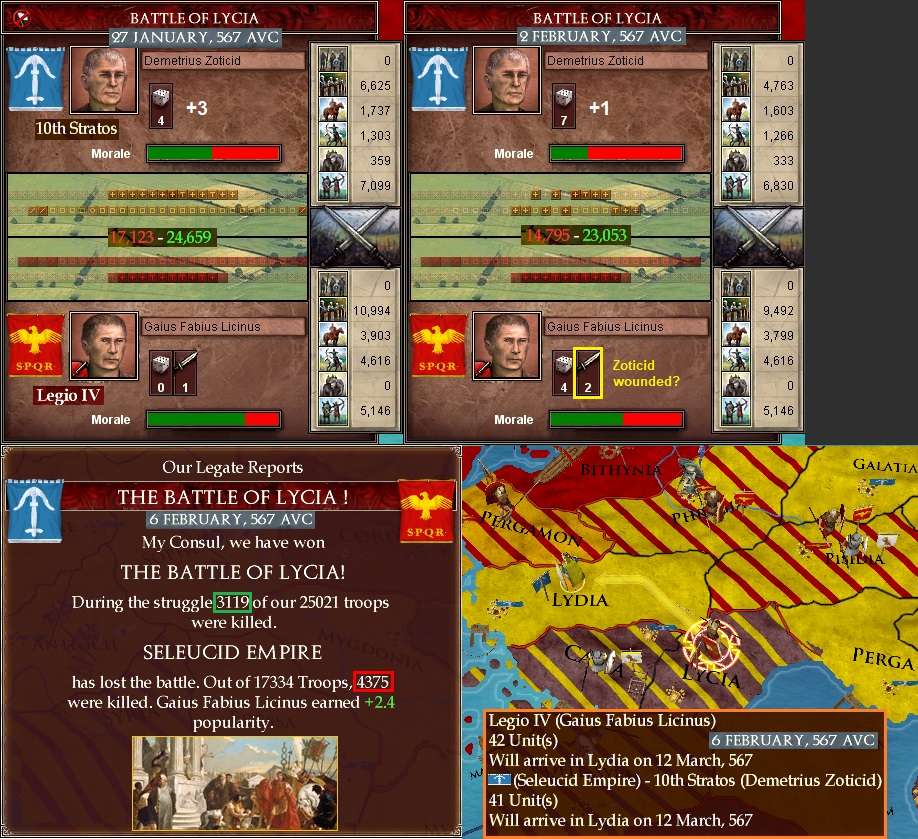

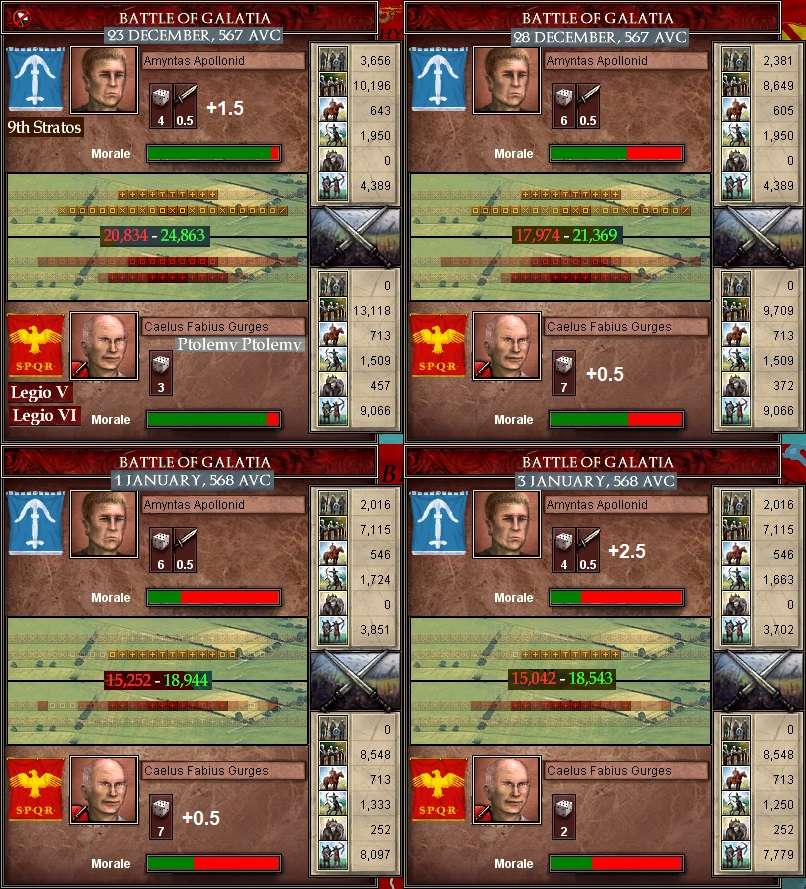

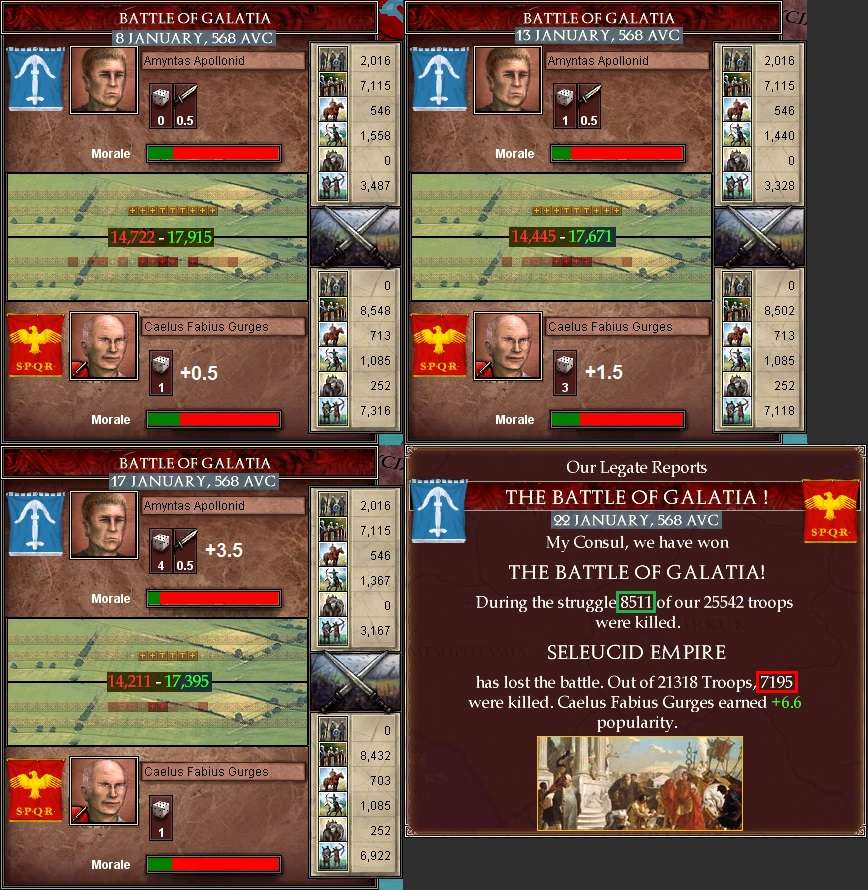

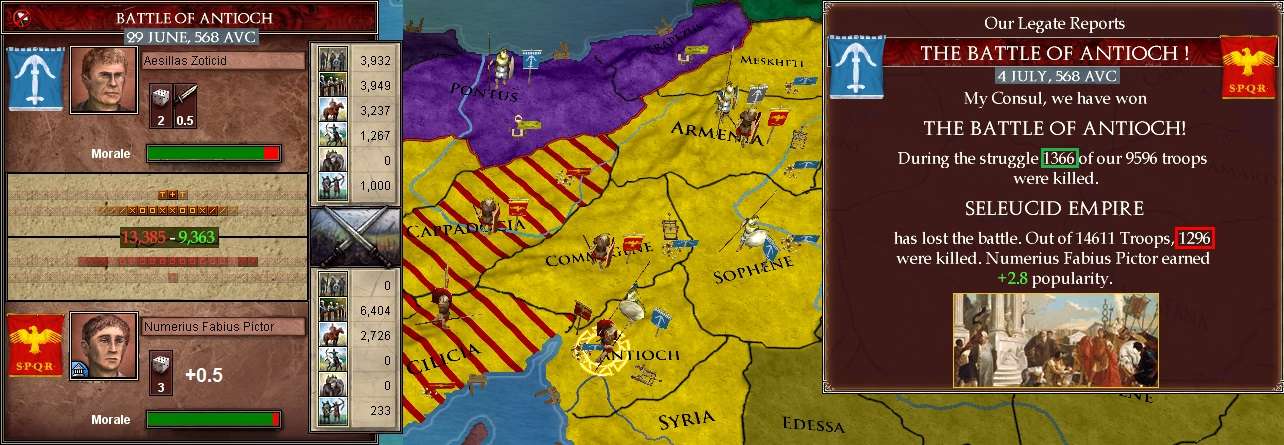

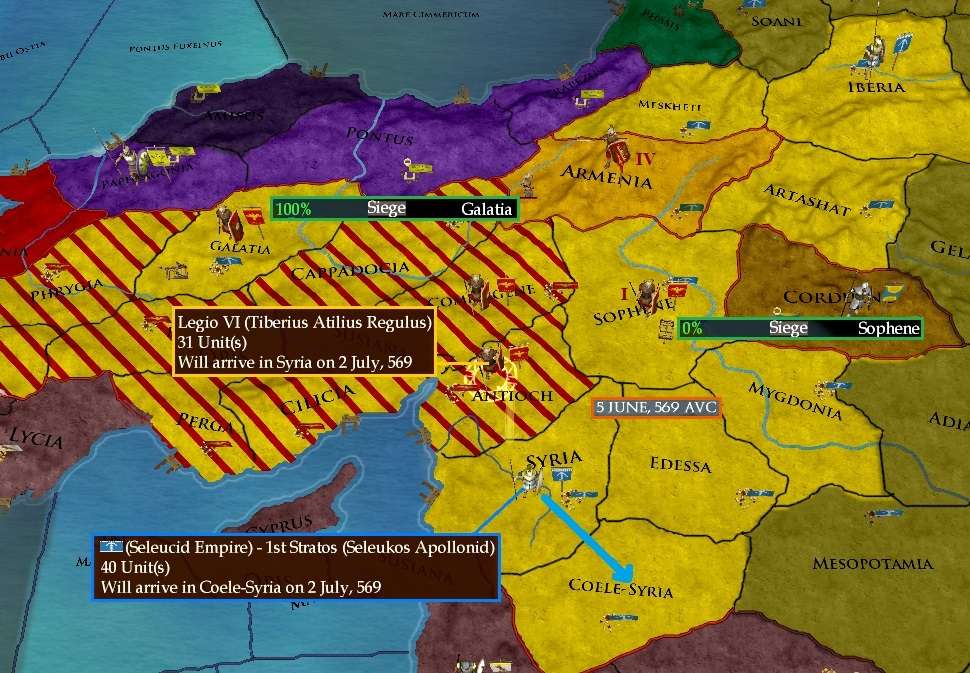

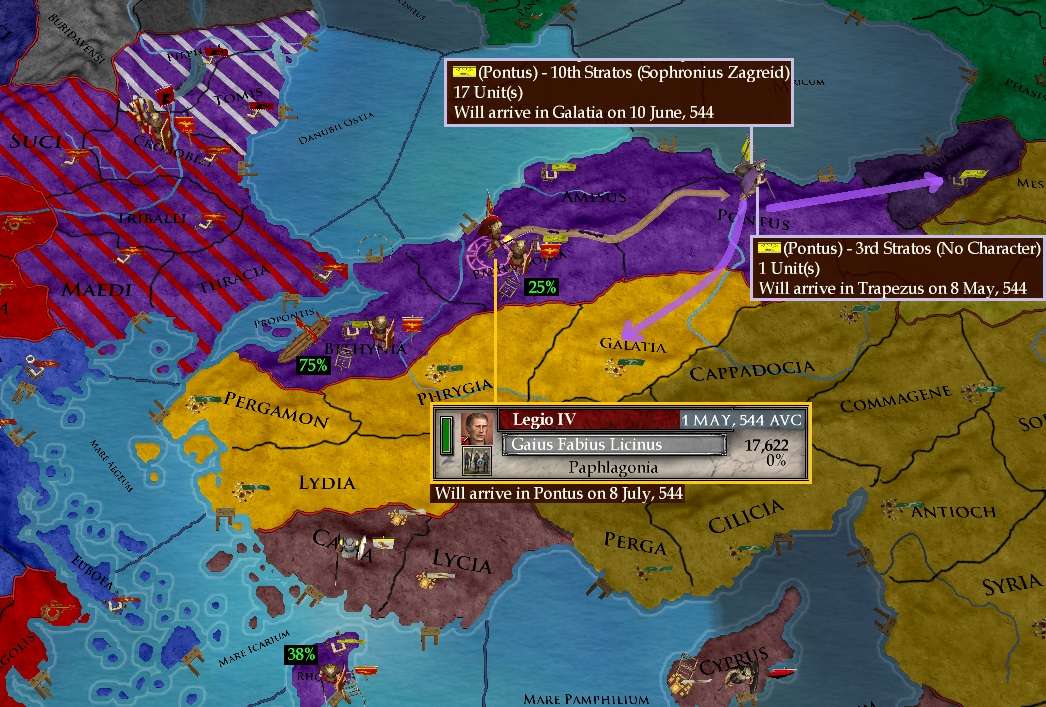

After a considerable break since any truly serious combat against Pontus, by early May things began to start brewing in Asia Minor. Sophonius Zagreid had concentrated 17 regiments in a new army (10th Stratos) in Pontus itself. For some reason he was marching them to Galatia and was due there in a week. Ignoring this, with his relief now in place to look after the siege of Paphlagonia, Licinus marched directly for Pontus with over 17,600 men.

“Let him traipse aimlessly around the Anatolian plateau if he wants to,” noted Licinus wryly to his key officers. “We have more troops on the way and if he wants to abandon his capital to grant me the glory of sacking it, so be it!”

In Asia Minor, Zagreid had finally arrived in Galatia on 17 June – and promptly marched straight back to Pontus again, where he was due on 1 July, just a week before Licinus would arrive. A pity, as it would mean Zagreid would still be able to arrange his defence on a river crossing. Licinus ploughed on undeterred.

“When in doubt about the enemy’s motives, I find it best to simply ignore them,” he ventured.

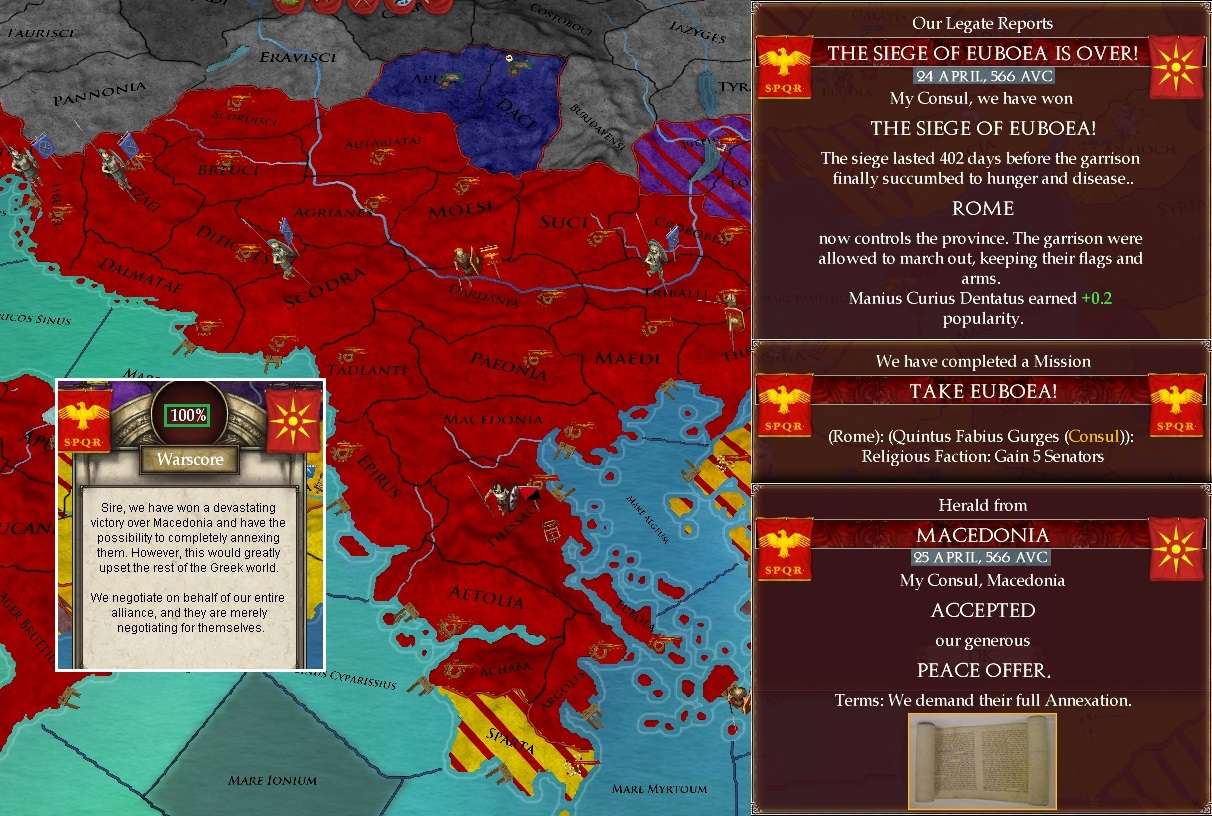

The next siege success came on 30 June with the fall of Crete to Gurges.

§§§§§§§

July 544

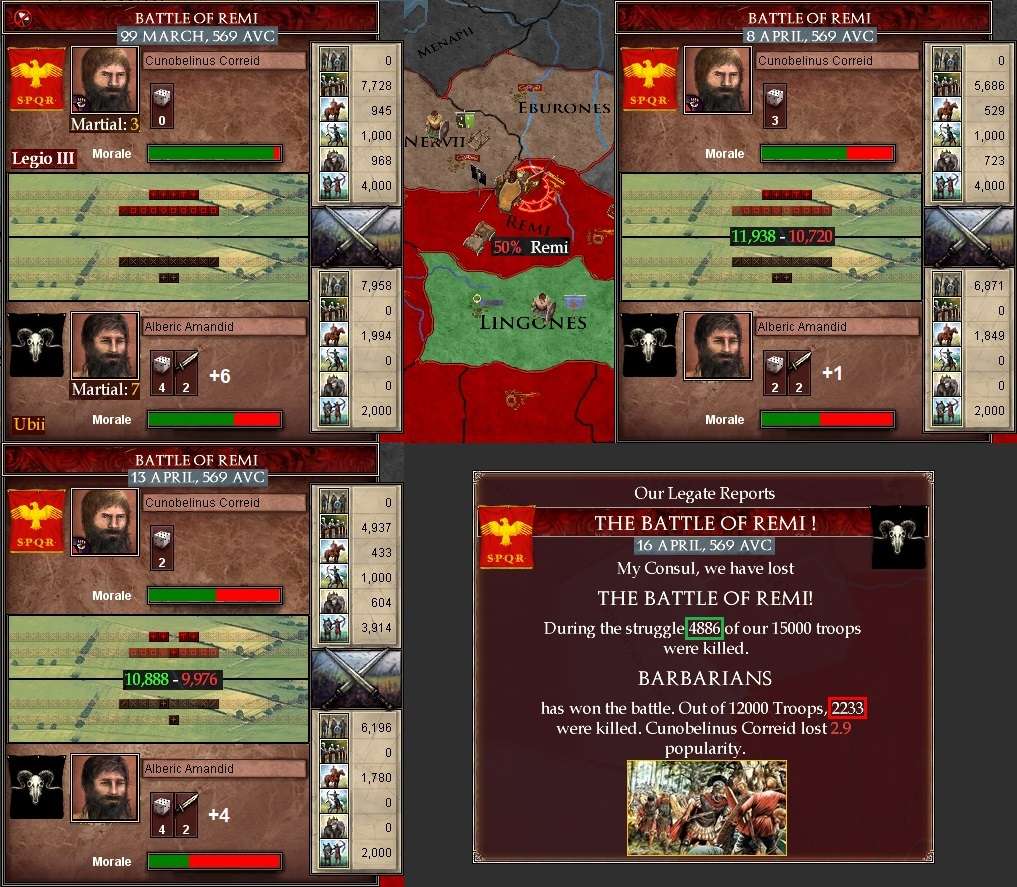

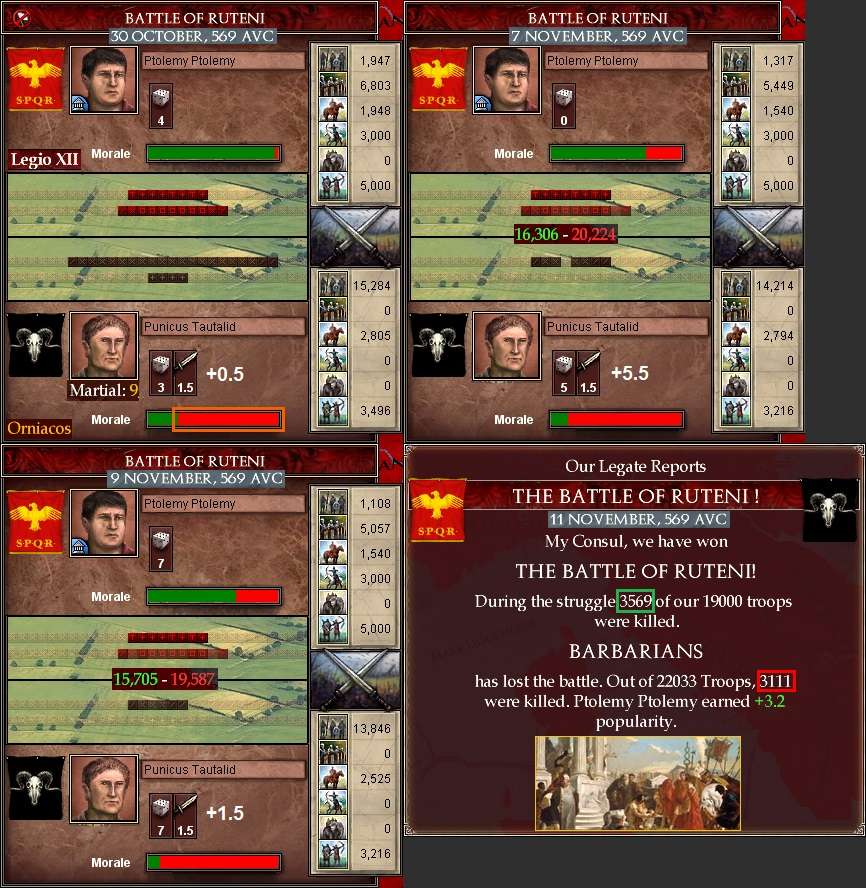

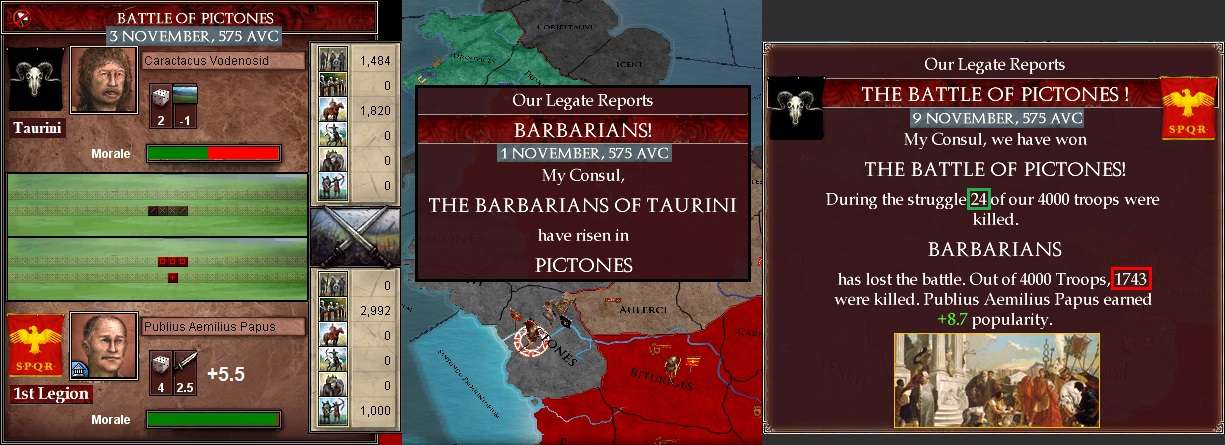

Back in Saguntum, as we saw in Section 1, M.C Scipio’s Legio X fought 14,000 Luggones tribesmen between 3-14 July.

Then on 7 July, the warlike Insubres returned to make the traditional forlorn follow-up attack on Caudex’s Legio I in Apuli. This time Caudex was better prepared and the battle was over the next day [Rome 5 v 4 Barbarian]. He lost 185 of his 15,704 men, slaughtering the defiant Insubres, taking 0.73 gold and 5,000 slaves as compensation for his trouble.

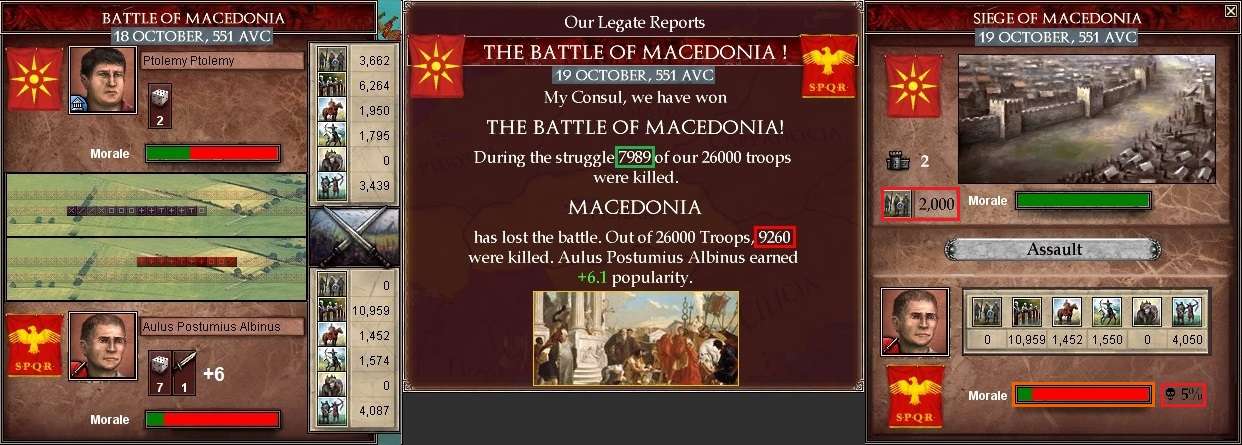

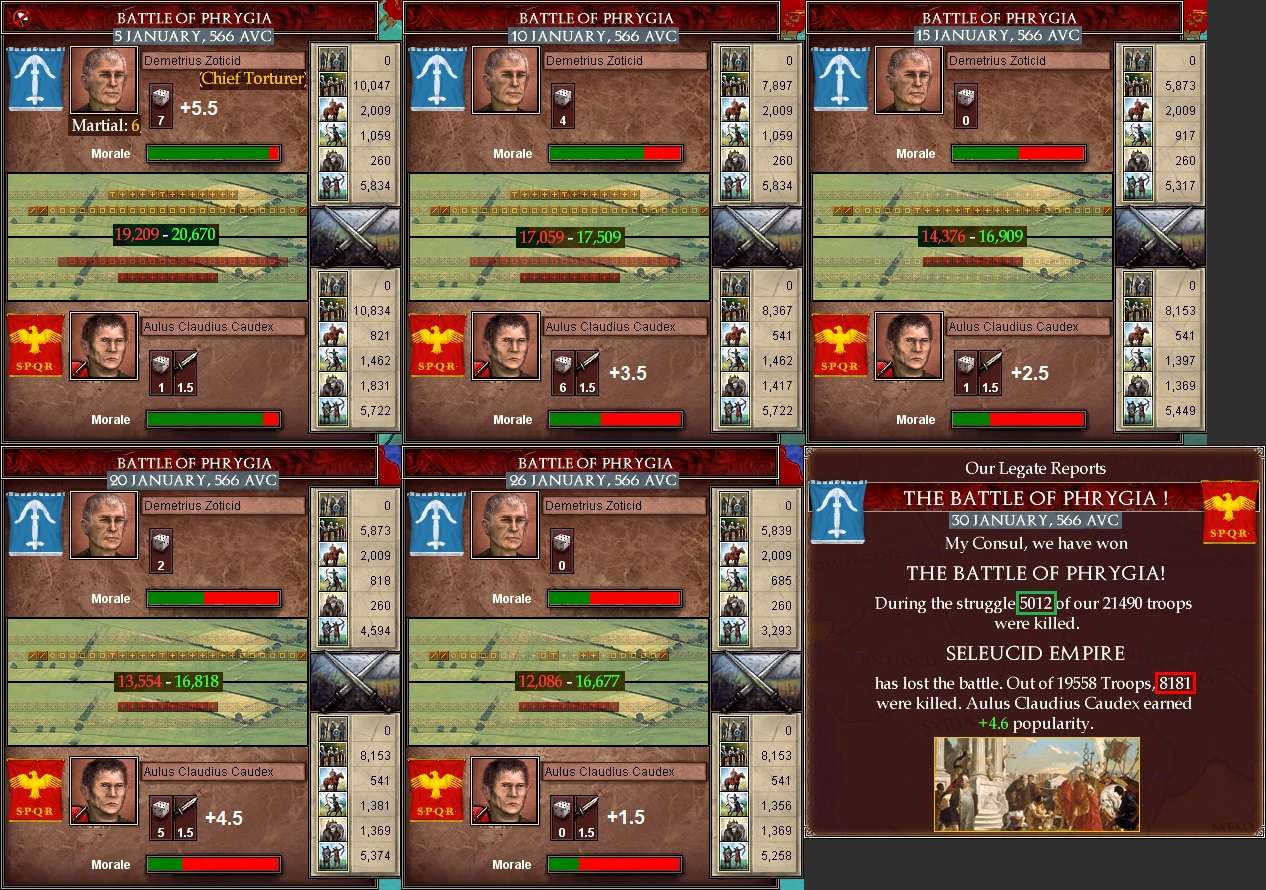

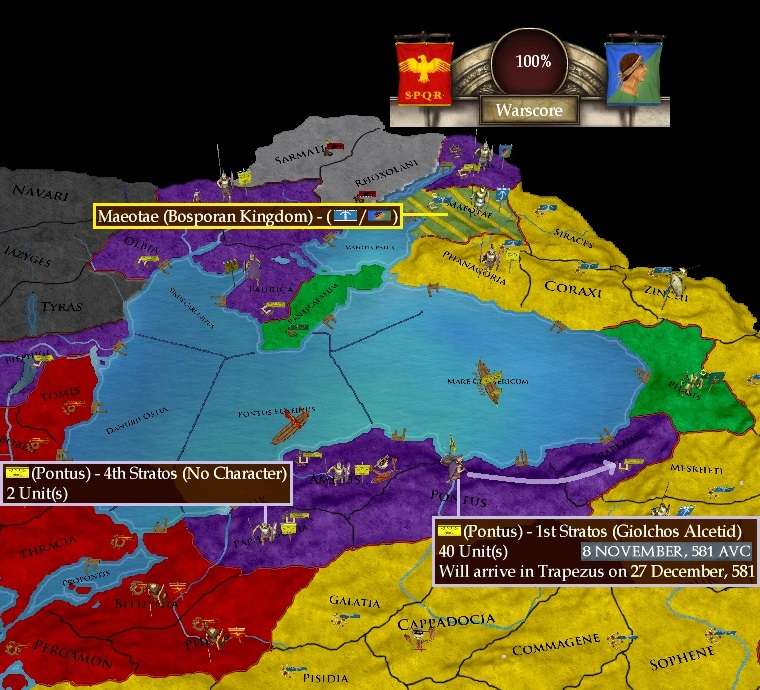

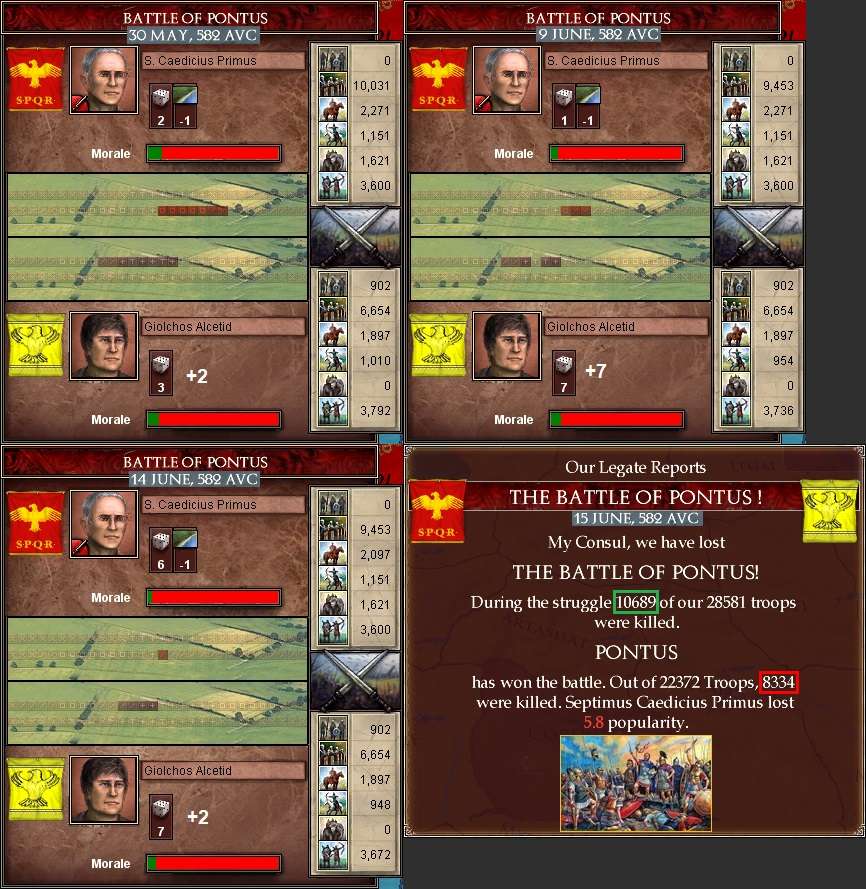

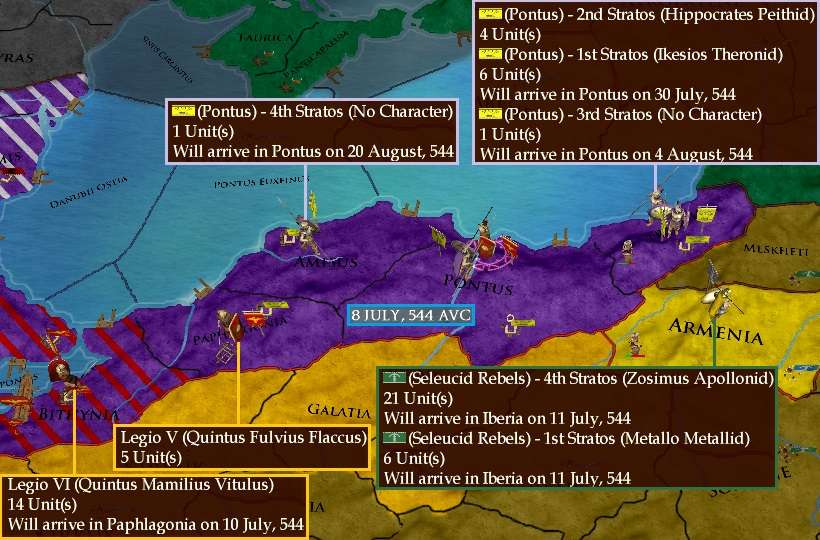

But the big showdown for this phase of the war started in Pontus on 8 July 544. Licinus had taken replacements during the march and now fielded a balanced force of just over 18,000 men. Waiting for him was the famed Sophronius Zagreid with 17,000 fresh troops, in a strong defensive position behind a river. In addition, it was revealed that Pontus had another 11 regiments in neighbouring Trapezus, with seven of them heading for Pontus. The first 6,000 troops were due to arrive on 30 July. Legio V in Paphlagonia was only a small besieging force and would be of no help. Legio VI was only just about to reach Paphlagonia in two days’ time: Vitulus could only hope to arrive in Pontus to either help celebrate with Licinus or avenge him if he was defeated. Licinus would have to win the battle himself, with the troops he had.

Legio VI (recovered to around 12,500 men by now) duly made it into Paphlagonia on 10 July and kept heading east, but would not reach Pontus until 16 September. In Illyria, as hoped for, the Massilians were now in Breuci and homing in on the barbarians in Autariatae.

All eyes now focused on Pontus. Licinus hadn’t marched this far “to sit on my arse and watch Zagreid’s men bathe and fish at their leisure”, he remarked before giving the order for his legion to advance. For once, he had the advantage in cavalry (just over 2,000 to none for Zagreid), and horse-archers (around 2,000 to 1,000). He had about 2,000 more heavy infantry than his opponent, whose only advantage was in archers (about 3,000 Roman to 5,000 Pontic).

The opening exchange was tight as the Roman maniples struggled across the river under a withering Pontic rain of arrows. Combined with Zagreid’s slight tactical edge, the Romans started to take unsustainable casualties [around 175 Pontic vs 540 Roman each combat round]. By 12 July Pontus had the numerical advantage, (16,040 men vs 15,381 for the Romans). If Licinus could not turn things around quickly, he knew he would be defeated and would have to try to salvage whatever remained on his legion through an ignominious and inglorious retreat. But he took these losses for another day and sought to reverse the trend with a renewed assault, which he would lead personally.

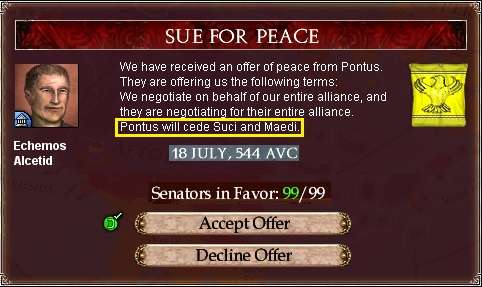

But turn the tables he did on 13 July: despite their good start, Pontic morale was still sinking more quickly than the Romans’ [the advantage here of the morale boost from having a Military faction Consul may have proven crucial – it was certainly helpful]. By 14 July the numbers were roughly even again and the Romans pushed forward with sudden enthusiasm. The battle would not last into a third [five-day by the game] phase. The Romans claimed the field on 18 July, despite having lost 700 more men in the battle than Pontus. But Licinus was exuberant, claiming one of the decisive battles of the entire war so far, deep in enemy territory, against a strong and well-situated force commanded by the enemy’s best general. And they were further from Rome than any Roman army had ever ventured.

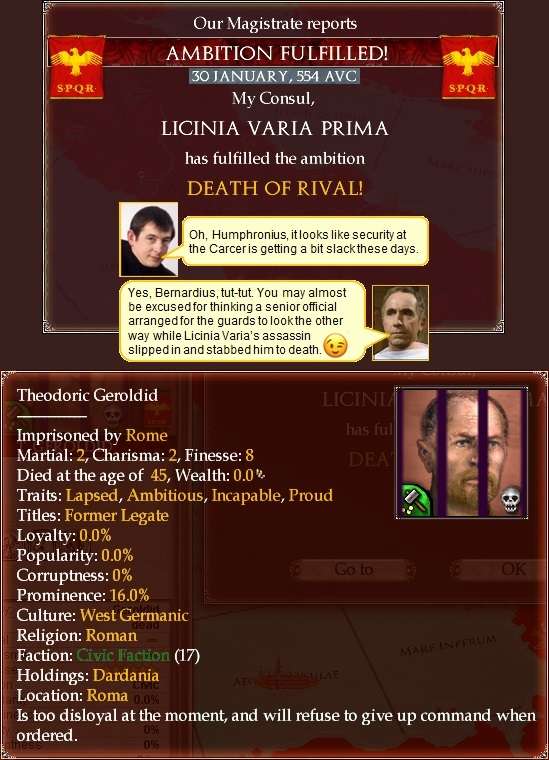

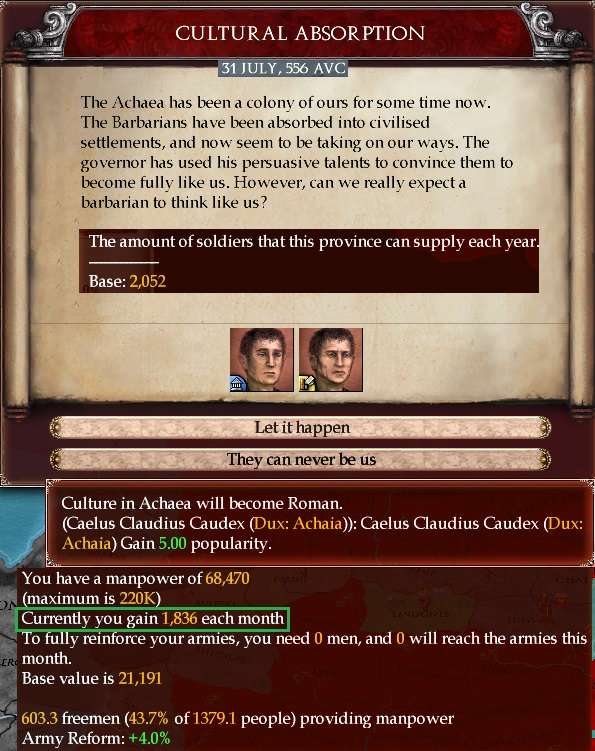

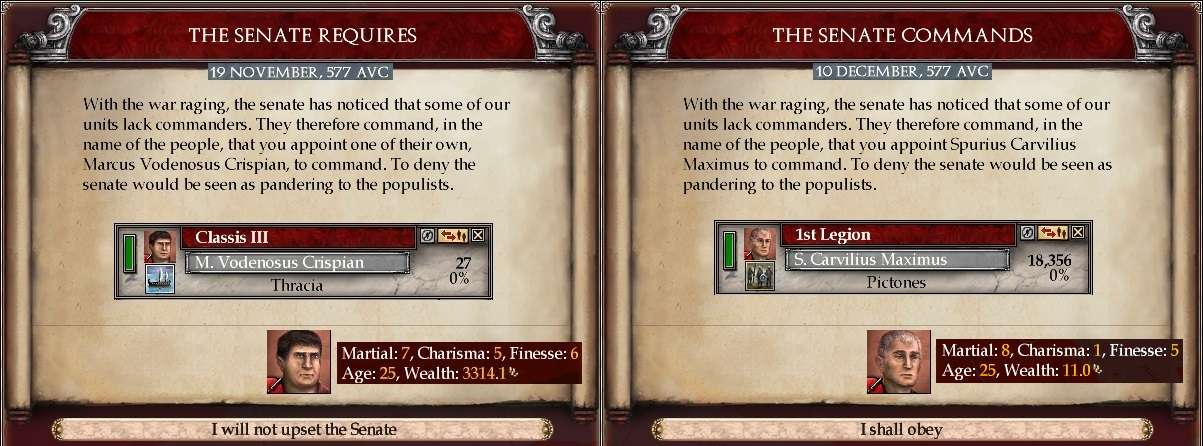

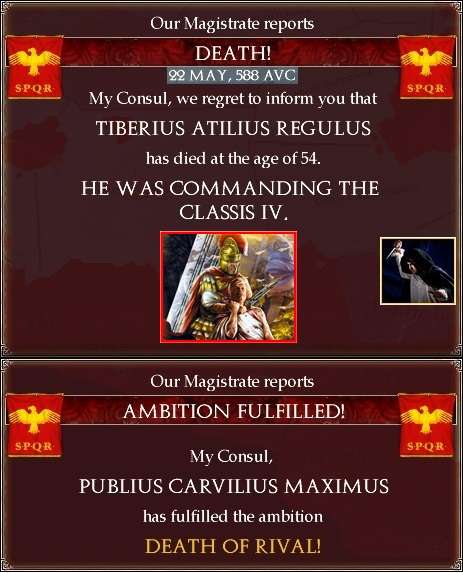

As this glorious victory was being celebrated, Caudex received warning that one of the ill-advised Senatorial appointments – a barely-civilised Germanic upstart called Theodoric Geroldid [possibly the brother of more famous Huneric Geroldid - I'll have to check in due course] – may be contemplating rebellion in Achaea.

“Send orders to Gurges in Crete,” he instructed his adjutant. “He is to take ship back to Greece where he is to try to relieve Geroldid of his troops. If he cannot be persuaded to do so peacefully, we’ll ship across more men and force him to do so at sword point.”

“So they all have cold feet?” was Maximus’ rhetorical question in response.

Humphronius nodded.

Unwisely, Bernardius piped up, making the kind of quip that was a trademark of his family. “So, it is a hotbed of cold feet, Consul?”

This simply earned him the mandatory fishy stare from both Maximus and Humphronius. Bernardius’ hesitant smile disappeared suddenly under this dual assault. He contemplated the rich fresco illustrating the floor of the Consul’s tablinum.

“Thank you, Bernardius!” said a scolding Humphronius. Turning back to Maximus: “Your decision, Consul.”

Maximus paused for thought.

“Bah!” exclaimed Maximus. “We have them backed into a corner. The answer is no. We will take Pontus itself and every remaining Pontic province we can reach. They will truly regret crossing us. I will advise the Senate this afternoon and then deliver the message personally to their ambassador.”

“Yes, Consul.”

Of interest, the surrender map shows the extent of all current enemy holdings. I have highlighted Pontus in purple, and the Seleucid Loyalists in red. They have been contained by the rebellion to the south-eastern corner.

“Yes, Consul.”

Of interest, the surrender map shows the extent of all current enemy holdings. I have highlighted Pontus in purple, and the Seleucid Loyalists in red. They have been contained by the rebellion to the south-eastern corner.

§§§§§§§

Finis

Last edited:

- 2