~ IX ~ 1172 – 1192

The last 20 years of the reign of Balinarayan should have been, as is the natural state of things, years of peace and reflection, for he was already over 50 years old and had ruled his kingdom for almost 40 years, having saved the world once from a demonic invasion. Instead, they revealed Balinarayan’s true greatness and his greatest temporal glory.

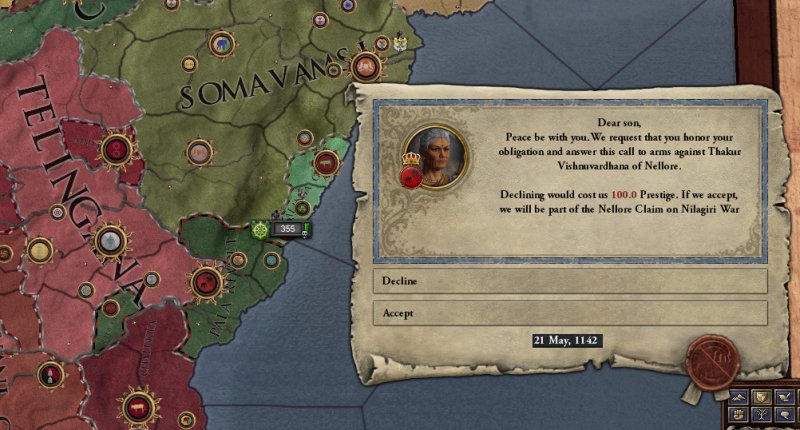

The kingdom of Malwa was ruled then by a young boy, the nephew of Balinarayan’s daughter in law, Shrimitradevi. She coveted the throne, and requested Balinarayan’s intervention for it. The maharaja was in deep thought for weeks over this request. The opportunity for his dynasty was undeniably huge, but the Paramara boy who ruled Malwa was allied to the Solanki maharajas, directly to the west. Together, those two maharajas could match Balinarayan’s best forces. For two and a half years he deferred his decision, while his army replenished its numbers and his treasury accumulated money. Then, in the summer of 1174 he made his decision – it would be war.

Over ten thousand warriors, some of them levies, others mercenaries, others the maharaja’s personal retinue, invaded the child-maharaja’s lands in two groups, close enough to support each other.

The enemy could just barely match Balinarayan’s numbers, but they were not as well led. One maharaja was a child while the other was an incapable old man, who ruled only in name. The two allies could not communicate well enough to come to a proper strategic decision, and so they chose to attack Balinarayan across a river, in a jungle.

The battle was fierce. There were 250 elephants on Balinarayan’s side, and 205 on the allied side. Maharaja Balinarayan was wounded, but the enemy was scattered, and the heir to the Solanki kingdom was taken prisoner.

After that, Balinarayan’s army was split into two. One half besieged the capital while the other half ravaged the country, and prevented any new enemy forces from linking up and becoming a threat. By the end of 1176 the war, and the kingdom, was won.

Balinarayan had taken two great risks – with his kingdom and with his life. But his kingdom triumphed, while his wound would healed, leaving a scar that brought him distinction, rather than any disfigurement.

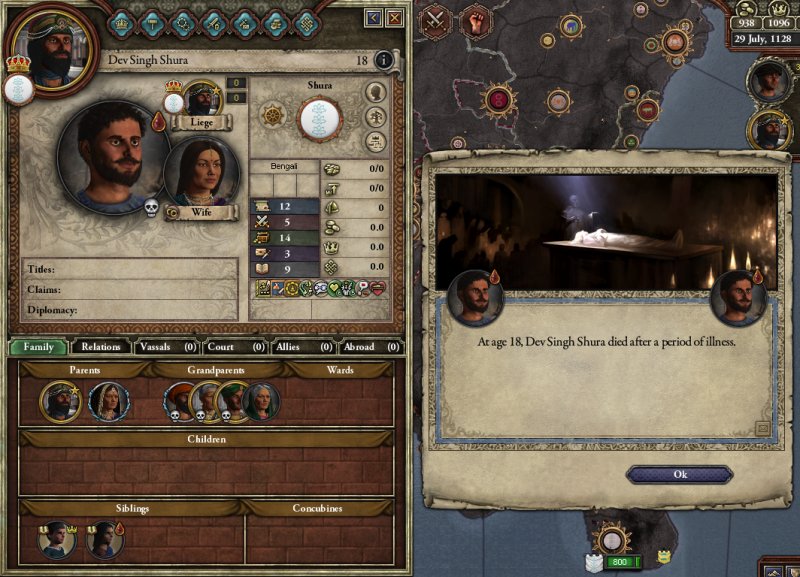

Shrimitradevi’s reign was a remarkably short one. She died of an illness after less than a year on the throne, leaving the kingdom to Balinarayan’s grandson, Kirti Singh.

Meanwhile, in the east, the thikana of Amaravati had known nothing but chaos and war for the past decade, as adventurers and rival petty rulers fought over it constantly. Balinarayan decided to bring peace to the region, and sent his army to bring it under his rule.

Although his local rivals had raised large armies of their own, they mostly expended them fighting each other. Of particular note was the employment of the Chosen of Ashoka, a religious order that had served Balinarayan’s predecessors in the past, by the embattled thakur of Amaravati. Since Balinarayan’s warriors were Buddhists, they had nothing to fear from the Chosen ones, unlike their Hindu rivals.

The war lasted from 1180-1183, and although the prize was a single thikana it lasted longer than the war for the Kingdom of Malwa. But at its end, Balinarayan became aware of a much more profitable use of his energies. He had undertaken a most dangerous adventure to win a new kingdom for his daughter-in-law and, ultimately, for his grandson. But now it came to pass that he was presented with an opportunity to claim another kingdom for himself. Having some royal Chola ancestry, he was able to contest the rule of its 12-year old maharani, Puvanti.

In July 1184, his forces invaded the kingdom from north and south. By August they had swept the field, in a decisive battle.

By September 1186, Balinarayan was proclaimed Maharaja of Tamilakam.

It took a further, smaller war to curtail the power of the former maharani, but in 1189 Balinarayan made Tamilakam his primary title. There were political considerations behind that move. Balinarayan was over 70 years old, and the kingdom of Tamilakam had a system of gavelkind succession. Were he to die suddenly, his lands would become divided, with his eldest son inheriting Lanka and his younger inheriting Tamilakam. By making the latter primary, he avoided that possibility. This move also made it possible to transfer the status of high crown authority from Lanka to Tamilakam, which the maharaja used to eventually change its succession laws to primogeniture.

After that, the old maharaja should have been content. But he was worried by the unbalanced nature of his family. He was maharaja, his grandson was maharaja, but his son was a mere thakur in the Maldives. As luck would have it, a third succession crisis gave him an opportunity to claim a kingdom of his own.

The kingdom of Kosala was ruled by a child, and prince Bhikhari was in an overlooked line of succession. The old maharaja assembled his troops for one glorious, last campaign. The battle fought was the most decisive yet, and all but ensured the kingdom by itself.

After that, it would be a short march to the capital to claim the kingdom. But Balinarayan, who was then 74 years old and had ruled for 59 years, departed from this world before the war could be properly concluded. Bhikhari, who was at the Maldives at that time, received the news and hurried to Kosala, where victory would be handed over to him on a platter.