To All: You so lucky I have so much study leave. Enough time for revising, writing updates AND playing further on in the game (which took a long time as there were a lot of events and even new nations to mod in). As such, update will be in the works today and be up, if not tonight, then tomorrow.

Eöl, Kampf_Machen(1), Enewald, Hardraade: Hmm, that wasn't as good as I could have done, I feel. I was a little rushed for time and space. The first three hundred or so words I had not actually envisaged beforehand, and I try to keep updates to two A4 pages. What I was crying out in my head to do was to write it narratively, because that would have been marvelous, but I feared I did not have time, didn't want to spend too long on a single battle (I mean, come on, we have been through over 30 pages and have covered under 16 years) and some people would not like to read a narrative in a history-book AAR. Thoughts on that for future reference will be taken into high account.

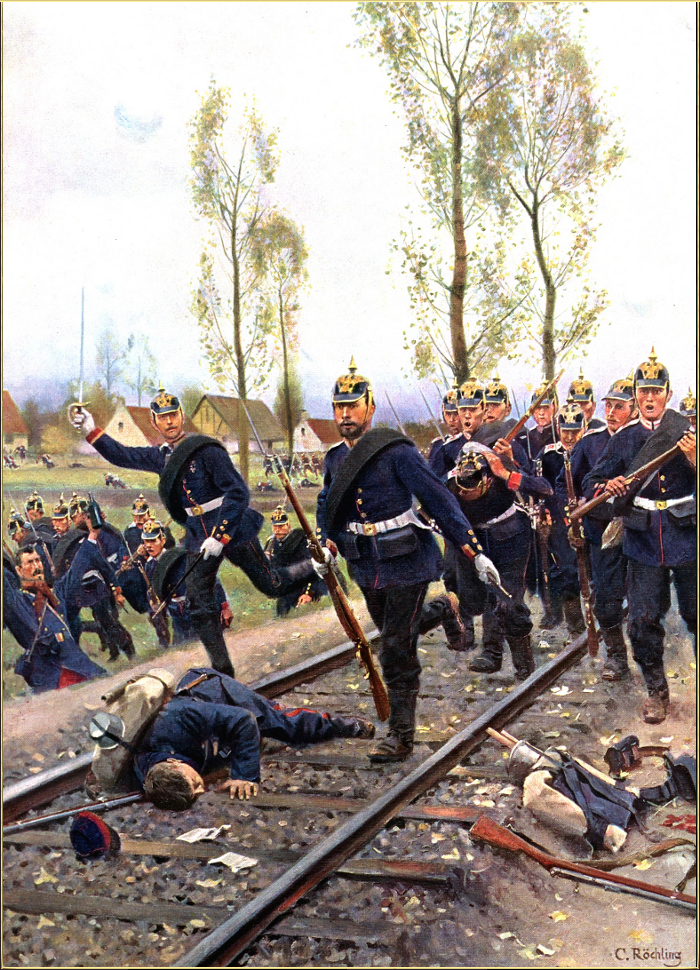

Avatar018, Kampf_Machen(2): Heh, I said I had decieved you all. The war getting bigger was simply in the size of the conflict. To go from battles of no more than 40,000 men total to one of almost 300,000 is quite a change of character to the larger. Frankly, the USA entering the war would be annoying, but I still have 60,000 men in the Americas (albeit locked up in Garrisons) not including the Mexican Imperial Army; I could hold 'em down. As for the Ottomans, they are in a defensive alliance with me

.

English Patriot, TRP, Kampf_Machen(3!): Not while Austria still had a field army of that size. But we can soon be rid of that. And then whats to stop me. Though some diplomacy, politics and badboy will get in my way, no doubt.

Ascalon: Thanks and welcome!

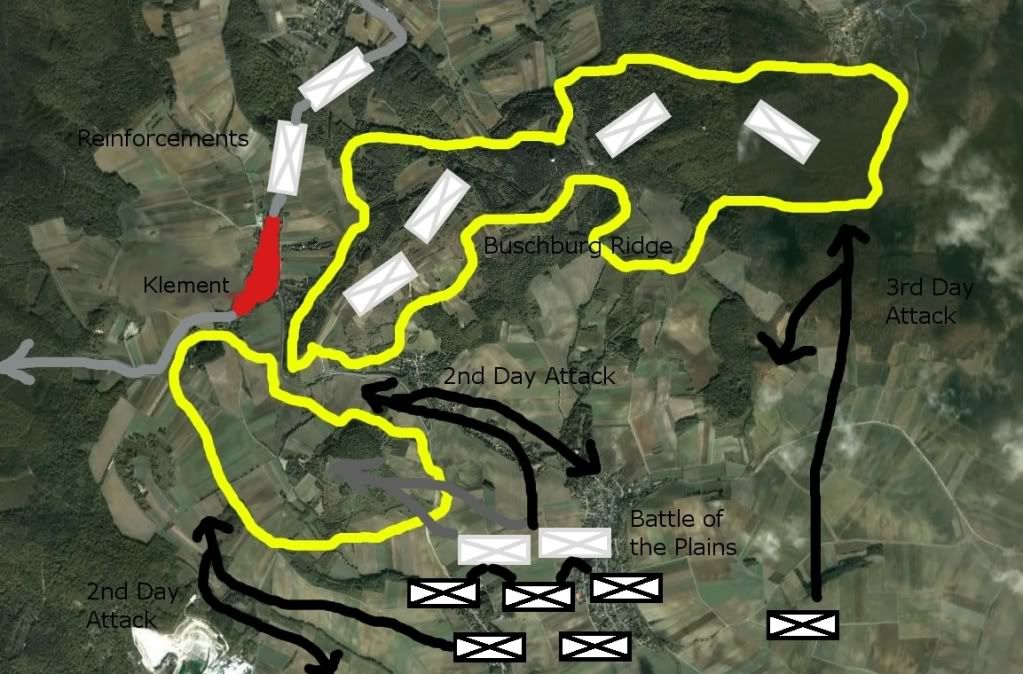

comagoosie: yes my paint skills... well... shall we call it an edwardian loss?

We'll cover failings of the military, in which Klement will play a major part, after the war is done.

Gwynn: Britain is pretty much neutral, but is not going to be friendly to a Germany who is tearing up Europe. I'll have to tread carefully with that one. Thankfully Britain and France are still slogging it out with no end in sight.