Presidents of the Republic of Gran Colombia

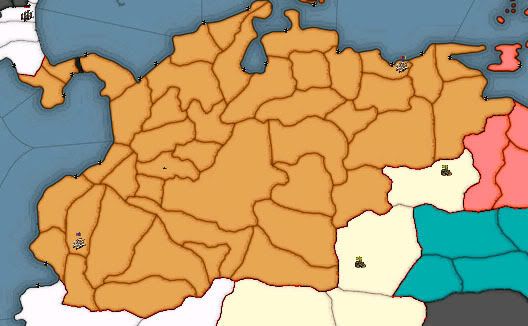

Simon Bolivar

Federalist Party

assassinated

(1819-1828)

Carlos Urdaneta

Federalist Party

(1828-1844)

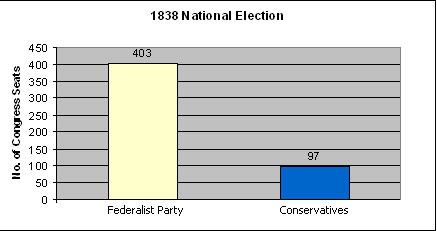

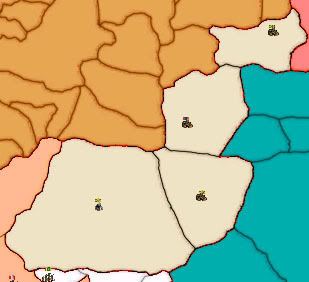

Miguel Caro

Conservative Party

lost Congressional majority

(1844-1846)

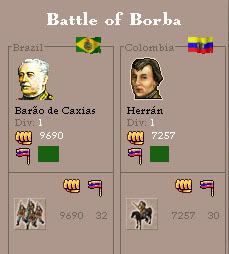

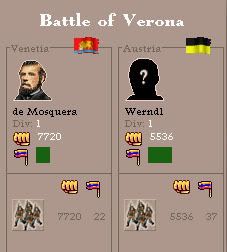

Enrique Herran

Liberal Party

resigned due to health reasons

(1846-1848)

José Lopez

Liberal Party

resigned

(1848-1854)

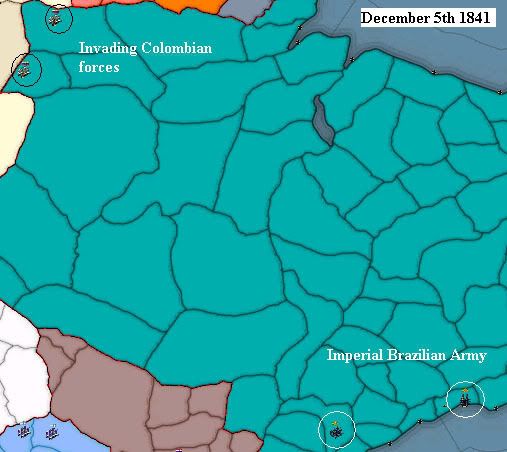

José Obando

Liberal Party

couped

(1854)

José Melo

Liberal Party

(1854-18??)

Federalist Party

assassinated

(1819-1828)

Carlos Urdaneta

Federalist Party

(1828-1844)

Miguel Caro

Conservative Party

lost Congressional majority

(1844-1846)

Enrique Herran

Liberal Party

resigned due to health reasons

(1846-1848)

José Lopez

Liberal Party

resigned

(1848-1854)

José Obando

Liberal Party

couped

(1854)

José Melo

Liberal Party

(1854-18??)

Last edited: