Blood and Iron – Germany’s road to modernity

1861-1929

-Part Two -

The Four Traditions

German politics was dominated through the period of 1861-1929 by four broad ideological traditions, in order of significance – Centrism, Liberalism, Conservatism (or Reaction) and Socialism. Each of these traditions had a major impact upon Germany and her political culture, and each tradition drew noticeably different conclusions from the analysis of German history.

Centrism

Variants: Christian Democracy (Radical, Moderate and Conservative), Political Catholicism, Karlist-MonarchismMajor Parties: Free People’s Party (FVP), German Centre Party (DZP) in various forms

Minor Parties: Republican People’s Party of Germany (RVPD), German Centre Party (DZP) in various forms

The German Centre Party that rose to national significance in the 1870s and 1880s was to create a movement with influence far, far beyond the Catholic heartlands of the South it was born it. From 1873 onwards parties originated in the Centrist tradition never failed to capture less than 30% of the vote, winning less than 1/3 on just four occasions and frequently finishing with a far higher share. Over the course of the period the Centre Party (in its various guises) and the Free People’s Party provided two Presidents, serving for a combined 21 years and six different Chancellors serving on eight separate occasions for a combined 31 years (only a shade under half of the entire period). With Centrists so defining the early Kaiserreich, the First Republic and even the Imperial Regency period of the Third Reich there is no German political tradition equal to Centrism.

Centrism was consistently defined by a commitment to democracy, to religious freedom, to Christian principles, to social stability and equality (to varying degrees) and a certain regionalism. Every political tradition viewed the unification in a slightly different way, for the Centrists the unification was only ever partially complete before the union with Austria in 1887 – widely celebrated as the greatest moment in German history. Likewise the era of 1869-1887 is often viewed darkly with Prussian domination identified as a threat to democracy and the individual cultures of the German peoples. This antagonism with the Prussian in turn made 1898 a highly celebrated date in the Centrist calendar – the foundation of the First Republic being seen, even by conservatives, as the moment when Prussian hegemony was broken forever. Although the splintering of the movement from the last decade of the 19th century through to the 1920s makes a single Centrist reading of history after the early 20th century problematic, the movement always retained a certain ideological coherence.

Major Figures:

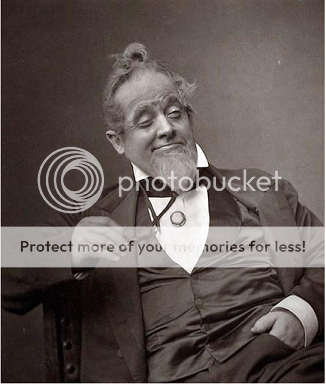

Ludwig von Windthorst

Born: Hannover

Lived: 1812-1893

Leader of Centre Party: 1869-1887

Chancellor: 1873-1878 and 1883-1887

Although other political figures held power for longer, Windthorst is arguably the most influential politician in the history of Germany from 1861-1929. Founding the Centre Party in 1869 he led it until 1887, serving as Chancellor for nine and a half years over two terms – most famously leading the DZP to an absolute majority (the only such majority ever achieved after 1863) in 1883. Defeating the Kulturkampf, Anti-Socialist Laws, laissez faire capitalism and Prussian centralism his governments also passed a significant amount of social legislation and, of course, led the march towards the unification with Austria in 1887. All elements of Germany’s Centrist tradition look back to Windthorst as their founder – for the Populists he was a fighter for the poor and needy, for the moderates a guardian of democracy and for conservatives the man who faced down efforts to destroy the traditions of non-Prussian Germany and won. A truly titanic figure.

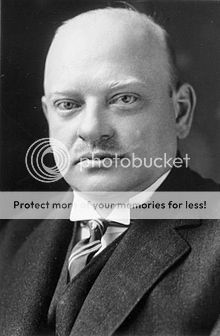

Adam Stegerwald

Born: Bavaria

Lived: 1874-1938

Leader of Free People’s Party: 1898-1920

Chancellor: 1898-1901

President: 1904-1919

Whilst Windthorst’s legacy was clearly of far less appeal beyond the Centrist tradition, Adam Stegerwald became a beloved symbol, not only of Populism, but of Republicanism as a whole. Popular with Socialists, Populists and Social Liberals alike he was actually a divisive figure within the Centrist camp, many being uncomfortable with his drift towards secularism, his close association with Germany’s Socialist movement and early radicalism. Becoming Chancellor at the mindboggling young age of 24 in 1898 (rising to the top of a highly youthful FVP during the chaotic years of Civil War and Revolution), he totally dominated the First Republic’s governments. Although his governments were successful in protecting the democratic character of the Republic, passing through a great deal of social legislation (building on the legacy of Windthorst), restoring German influence abroad and modernising the economy despite the relative economic hardships of the 1910s his legacy was greatly tarnished by his final years. The years leading up to 1920 saw the Republican camp splinter, Hindenburg claim the Presidency in 1919 (thereby removing the FVP and its allies from power) and finally his party face destruction at the polls – leading to his retirement from politics at the age of 46. Although he would re-enter politics during the 1930s as a moderate Republican, never again would he achieve national influence. At icon to ‘progressives’ of all ideological shades and a controversial figure, Stegerwald held governmental power for longer than any other individual during the period.

Franz von Papen

Born: Westphalia

Lived: 1879-1964

Leader of German Centre Party (Monarchist): 1919-1920

Leader of German Centre Party: 1920-1925

Chancellor: 1920-1925

Franz von Papen is a highly controversial figure in German political history. It was his rebellion, more than any other single factor, which allowed the Hindenburg to rise to the Presidency and the support of his Monarchist Centre Party that allowed the right and far right to achieve power in the 1920s. However, without his individual contribution Karlist Monarchism (a monarchism that combined support for the Habsburgs with demands for constitutional monarchy in Germany) would never have emerged as a nationally significant movement and conservative Centrism would never emerged independent of its moderate Republican leadership. Therefore, for a certain brand of conservative Centrist – Papen is a heroic figure who stood against the Republican mainstream and came within a slither of guiding the Habsburgs back to power all in the space of a few years. Although ultimately failing in his aims, Papen’s position in German, and Centrist, history is unassailable.

Liberalism

Variants: Social Liberalism, Progressive Liberalism, National Liberalism, Classical LiberalismMajor Parties: German Progress Party (DFP), National Liberal Party (NLP), Free People’s Party (FVP)

Minor Parties: Liberal Union of Germany (LVD), German Democratic Party (DDP), German National Liberal Party (DNLP), Republican People’s Party of Germany (RVPD)

German Liberalism, although a highly significant force in German political history (especially up until 1890s) was often at odds with itself. The central cleavage regarded the relationship between the economy and elites. Pre-War Liberalism was divided between the Progressive Liberalism of the DFP, with its undying commitment to democracy, its anti-elitism and willing to compromise over its belief that it stood up for the common man, and National Liberalism that was highly supportive of the Prussian establishment, was more ambivalent towards democracy, carrying an altogether more authoritarian edge. After the war Liberalism was again divided as Social Liberalism (arguably the successor of Progressive Liberalism) turned away from laissez faire whilst retaining the anti-elitism and democratic commitments of old, National Liberalism appeared to strip itself of much of its Liberal nature in dissolving into the DNVP (although also having an influence on the DDP) whilst the DDP stood up for a traditional Progressive and Classical Liberalism with a rather more firebrand insistence on laissez faire leading the party towards National Liberalesque conclusions and collusion with the Right.

The Liberal vision of German history clearly divided between National and Progressive-Social Liberal traditions. In contrast to Centrism and Conservatism, Liberals tend to originate their narrative of German unification in the Revolutions of 1848, where they believe the project of unification truly began. The Forchenbeck Prussian government of 1861-1863, which unified Northern Germany, is regarded as the force that restarted the process begun in 1848 and unleashed the unstoppable force of German nationalism – which eventually achieved the full unification of Germany in 1869. With 1887 seen as being of secondary importance, especially for non-Austrian Liberals, it is in 1869 that the united Liberal viewpoint diverges into two different accounts. Whilst National Liberals stand firmly behind the ‘Prussian camp’ in the ideological struggles of 1869-1887, Progressive and especially Social Liberals tend to be more ambivalent – many even tactically supporting the ‘Centrist camp’! There were no stronger proponents of colonialism in the 19th century that the Liberals, of all shades, such was the popularity of Liberal imperialism that as late as the 1920s prominent Liberal commentators still talked about the possibility of acquiring a new Empire at the expense of Spain, long after colonialism had ceased to be either desirably or feasible. 1898 remains a contentious date within the Liberal School. For Social Liberals, it marks the birth of a golden age of democracy complimented by the good governance of the FVP, for the Classical Liberals of the DDP the Weimar Republic was a cherished for its institutions but derided for the tyrannical economic interventionism of the FVP and their governments whilst National Liberals staunchly opposed the regime – disliking both the governments it produced and the institutions it was founded upon. In contrast to other school of thought, Liberalism was actually brought much closer together through the trials of the 1920s – Social, National, Progressive and Classical Liberals all uniting behind the Second Republic in their mutual loathing of dictatorship.

Major Figures:

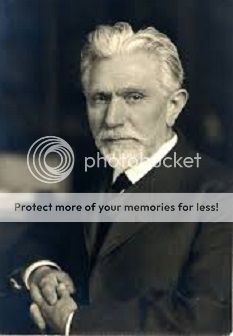

Max von Forchenbeck

Born: Westphalia

Lived: 1821-1888

Leader of German Progress Party: 1860-1863

Leader of National Liberal Party: 1863-1869

Leader of Liberal Union of Germany: 1877-1883

Minister-President: 1861-1863

Forchenbeck is many things to German Liberalism; the founder of modern party politics, of modern Liberalism, of the Progress Party, of National Liberalism, the man who kick started the process of unification and who stood consistently for Liberal unity. He is also the man who divided Liberalism, failed miserably to return to power after 1869 and oversaw the rapid decline of Liberalism under his ill-fated LVD between 1877-1883 – the period when Centrism definitively supplanted Liberalism as the dominant ideological school in Germany.

History will best remember Forchenbeck for his role in the unification of the 1860s. After stunning leading the DFP to power in 1861, in the process revolutionising German politics in his reorganisation of Prussian Liberals into a modern political machine, his policies quickly provoked the conflict with France that allowed the North German states to unite under Prussian leadership. Seeing his party grow unwieldy, Forchenbeck split off from the DFP to form the National Liberal Party – retaining governmental power from 1863-1869 as the junior partner in an alliance with the Bismarckian conservatives that successfully achieved unification in 1869. However, his moderate positions within the NLP saw his lose the leadership to radicals in 1869 and travel through the political wilderness over the course of the following decade his politics, somewhere between Progressive and National Liberalism, leaving him alienated from both the DFP and NLP. His dramatic comeback came in 1877 when he led a campaign to achieve Liberal unity, forming the Liberal Union. It was believed that under a single party Liberalism would be capable of overcoming the rising might of Centrism, and a resurgent Conservatism. Instead the LVD achieved the worst results in German ‘Liberal’ parties would ever achieve before 1920 with 1878 and 1883 both seeing the LVD achieve a pathetic ¼ of the vote (considering that the two Liberal parties had been used to gaining a minimum of 40%, this was a dramatic fall from grace). Forchenbeck never recovered from the dissolution of the Union in 1883 – failing even to be granted a ministerial position when the Liberals returned to power in 1887. Despite his mixed legacy, Forchenbeck can safely be regarded as the father of German Liberalism.

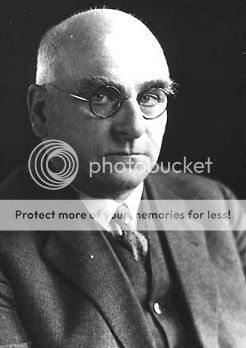

Eugen Richter

Born: Brandenburg

Lived: 1874-1938

Leader of German Progress Party: 1883-1897

Leader of German Democratic Party: 1897-1909

Chancellor: 1887-1893 and 1901-1909

For 26 years Eugen Richter dominated the Progessive-Classical wing of German Liberalism. Leading the reconstituted DFP from 1883 he infamously supported Windthorst’s removal of the Anti-Socialist Laws in that year on democratic grounds, despite his virulent hatred of Socialism. Becoming Chancellor from 1887-1893 (the only man to serve in the role in both the Kaiserreich and First Republic), at the head of a an alliance of Progressive and National Liberals, and with the parliamentary backing of Conservatives he returned to power after the Great War at the head of the newly formed German Democratic Party which regrouped various Liberals around a democratic-Republican laissez faire agenda. Initially working with the revolutionary parties (FVP and SPD), he coordinated the shift of the DDP and DZP from alliance with the revolutionaries to alliance with the monarchist. Becoming Chancellor of this conservative government from 1901-1904 he retained the Chancellory even after the FVP and SPD returned to government with Adam Stegerwald’s Presidential victory of 1904. However, in the last years of his political career he witnessed the rise might of the Austrian School influenced radical economists with the DDP – who’s eventually towering influence within the party led the DDP into opposition, obscurity and eventually alliance with the Right.

Adam Stegerwald

Born: Bavaria

Lived: 1874-1938

Leader of Free People’s Party: 1898-1920

Chancellor: 1898-1901

President: 1904-1919

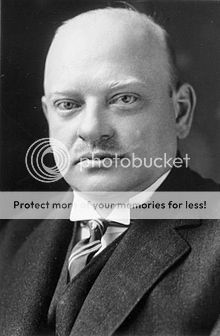

Gustav Stresemann

Born: Brandenburg

Lived: 1878-1947

Leader of German National People’s Party: 1913-1924

Leader of German National Liberal Party: 1924-1935

Chancellor: 1919-1920 and 1928

President: 1928-1933

After 1919 he served a brief one year term as a transitional Chancellor – rapturously welcoming the Right wing coalition that brought down the First Republic following the 1920 elections and enthusiastically supporting its early years in government. This enthusiasm was not to last, as the Regency regime lurched from crisis to crisis, all the while failing to establish a solid constitution (Hindenburg serving as Regent from 1920-1925 due to disputes between Habsburg and Hohenzollern claimants to the Imperial throne) Stresemann turned against his own parties. In the end it was not his collaboration with Fascists nor Republican Liberals nor even Catholic Centrists that brought an end to the always strained relationship between Stresemann and his party, it was his decision to turn against the fundamental basis of the German National People’s Party – unconditional support for the House of Hohenzollern. When Stresemann voiced support for the claims of Karl von Habsburg whose commitment to constitutional monarchism had impressed him he was expelled from the party along with a small band of followers who groups with Republican Liberal groups to form the German National Liberal Party (DNLP).

After the wilderness years of the military dictatorship that ruled Germany from 1925-1928 Stresemann once again returned to the forefront of German politics as he played a leading role in transitioning Germany from the military dictatorship of the Third Reich to the parliamentary democracy of the Second Republic, serving as Chancellor through much of 1928 before being elected as President in the same year. During these turbulent months he negotiated with leading members of the dictatorial ruling junta, the Imperial court, Karlist Centrists, Moderate Republicans, Conservative magnates and most crucially Socialists – a unique ability to find a degree of common ground with such a myriad of groups allowing him to stand out as the unlikely face of the 1928 Revolution.

Conservatism

Variants: Prussian Traditionalism, Bismarckian Conservatism, Authoritarian Monarchism, Fascism, National IntegralismMajor Parties: German Reich Party (DRP), German Conservative Reich Party (DKRP), German National People’s Party (DNVP), German Fatherland Party (DVP)

Minor Parties: Conservative Party (KP), German Workers’ Party (DAP)

Conservatism was the third ideological force in Germany through the era, always battling between an internal conflict between the an obsessive fascination with backward looking traditionalism and a strong desire to see a Prussian led Germany secure her destiny as Europe’s mightiest nation. The initial rift within Conservatism was caused by the creation of the North German Federation in 1863 as the Prussian Traditionalists clashed with Bismarck and his followers who aligned themselves with the National Liberals – achieving unification with the Southern states in 1869 and then embarking upon their infamous project of ‘nation building’ famously typified by the Kulturkampf. The early 1870s would see Conservatism evolve yet further, with the unification allowing the division between the Traditionalist KP and more modern thinking DRP to fade away as the parties united into the DKRP German Conservatives also distanced themselves from the National Liberal project. Seeing that policies like the Kulturkampf were, rather than conducive to order, a major source of instability – the rise of a radical regime of Progressive Liberals and Centrists to power in 1873 proving to be a major shock – Conservatives moved into a position of neutrality in the struggle between National Liberals and Centrists, playing both groups off one another. Uncommitted to any grand project of restructuring the German nation, unlike Liberals and Centrists, German Conservatives were primarily focussed on fostering internal stability and preventing the international isolation of Germany. Both these missions collapsed in spectacular fashion from 1896-1898, leaving German Conservatism in a state of crisis.

The Conservatism that emerged from the closing months and years of the 19th century idolised the Kaiserreich, the House of Hohenzollern, the Prussian military establishment (including, in many circles, the Ludendorff dictatorship) and all values in opposition to the First Republic. Aside from a brief spell in government from 1901-1905, and of course the late 1910s; German Conservatism remained relatively stable but isolated from the rest of the political establishment. Despite this, the tendency remained surprisingly vibrant. The emergence of Fascism in the latter Noughties split an aggressively vibrant revolutionary faction from the Conservative mainstream (consisting of roughly 1/3 of the Conservative voting public) as Anti-Democratic, Anti-Republican, Anti-Marxist and Anti-Semitic viewpoints hardened on the Right. After so many years in opposition Conservatives were brought to power from 1919-1928 – gaining free license to crack destroy the First Republic, crack down on ‘democratic excesses’ (most notably after the coup of 1925) and enter battle with the Socialist dominated labour movement. However, rather than look to radically restructure society, or even decide upon a clear form of government, the Conservatives merely restored decrepit old elites and undermined those within their camp whose Totalitarian ideas might have given the listless regimes of the 1920s a degree of energy with which to restructure society, or those whose more democratic outlook would have made a conservative leaning democratic regime possible. The 1920s once more divided Conservatism – the moderates aligning with either a revived National Liberalism or Karlist Centrism, the radicals rallying around the Integral Nationalism of the Fatherland Party.

Unsurprisingly, the Conservative view of German history differs wildly from both the Centrist and Liberal traditions. Although during the 19th century itself Conservatives were divided on the merits of unification, by the 20th century the hold of German nationalism meant that unification was viewed as a complex inevitability. The central theme of Conservatives viewing the unification period was that German unity had to be achieved, but only in a way that would not cause chaos and social strife within the country and would not line up the Great Powers of Europe against the German nation – threatening her continued existence. It is for these reasons that the defeat of the Liberal Revolutions of 1848 is identified, not as a glorious failure, but as an important victory – although unification was delayed, a Revolutionary regime that would threaten the social fabric of the nation and instantly become an enemy to Europe’s crowned heads was avoided. The unification of the 1860s is identified as the only true unification of the German nation – with the process being completed upon the proclamation of the Empire in 1869. The credit for this triumph is laid at the feet of the mighty Prussian Army – twice victorious over France during the decade – and the diplomatic genius of Otto von Bismarck, the darling of Conservatives nationwide. The following two decades are seen as a golden age with the Conservatives, under Bismarckian tutelage, ensuring internal stability by arbitrating between Centrists and National Liberals whilst having a calming influence over foreign policy – Germany’s strong position during this period despite the conquest of an overseas colonial Empire being a source of endless praise.

The great disaster was the annexation of Austria in 1887 – destroying the balance of power, the annexation made German isolation and war inevitable, it provided the country with a large injection of Catholics and ethnic minorities to threaten the internal stability of the Empire and set the troublesome precedent of removing a crowned head from power in the case of the Austrian Habsburgs. Left in a concerningly weak state at the outbreak of war in 1896 German was then betrayed by Jewish influenced Socialistic and Liberal movements who caused the collapse of the Prussian war machine and created a Jew-Republic in 1898 having failed to achieve a Communist style social revolution the previous year. The First Republic then became the earthily representation of all that was wrong with the world – its eventual destruction in 1920 being universally welcomed. However, the unity of Conservative opinion ends here. After 1920 opinion divides between the scattered advocates of a conservative constitutional monarchy, ultra-traditionalist monarchists, militarists, revolutionary Fascists and Integral Nationalists.

Major Figures:

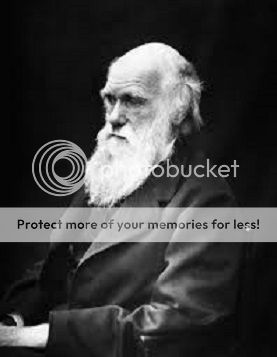

Otto von Bismarck

Born: Prussian Saxony

Lived: 1815-1895

Leader of Free Conservative Party: 1863-1869

Leader of German Reich Party: 1869-1873

Leader of German Conservative Reich Party: 1873-1888

Chancellor of North German Federation: 1863-1869

Chancellor of German Empire: 1869-1873 and 1878-1883

Otto von Bismarck, the Iron Chancellor, remains the most towering figure in German Conservatism to this day – a hero to Nationalists and Conservatives of all shades and varieties. Having first come to prominence in 1848, playing an important role in the defeat of the Revolution of that year in Prussia, Bismarck gradually rose to the top of Prussian politics. In 1863 he led a breakaway faction of right wingers who formed the Free Conservative Party – his modernising Conservatives, committed to German unification – would enter government that year alongside the National Liberals to forge an alliance that would allow Bismarck to remain Chancellor of North Germany and later the German Empire from 1863-1873. During this period he played a key role in the unification of Germany – his diplomatic acumen allowing a Prussian led German Empire to emerge without a coalition of Great Powers emerging, strong enough to prevent the unification. During the mid-1870s he changed his course from being a strong advocate of the National Liberal project to a more neutral position regarding the conflict between the North and South – attempting to build a general national consensus around the Imperial regime and against potentially dangerous revolutionary movements. In the end, his attempt to balance both the Great Powers and the forces of Liberalism and Centrism failed in the mid-1880s – the Centre Party’s spectacular electoral victory of 1883 bringing an end to the Anti-Socialist Laws, seeing a single political movement emerge as dominant and facilitating the annexation of Austria, a move which was seen to have led directly to Germany’s international isolation. A great prophet of doom, when Bismarck was bundled away from the leadership of the DKRP, a party he had founded, in 1888 after three decades at the forefront of German politics, he predicted that the annexation of Austria would lead Germany into a conflict against a coalition of Great Powers that she would inevitably lose, causing the downfall of German civilisation.

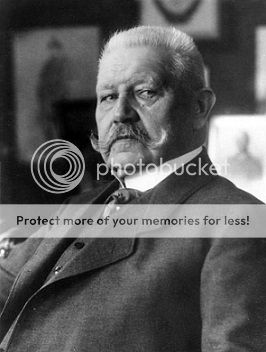

Paul von Hindenburg

Born: Posen (East Elbian Prussia)

Lived: 1847-1933

President: 1919-1920

Regent: 1920-1925

Unlike the other figures mentioned in this text, Paul von Hindenburg was not primarily a political figure but a military one. A member of the old, East Elbian, Prussian military-aristocracy he had a long and distinguished record in the Prussian, and later German, Army – beginning his career in the 1860s he retired in 1915 as Chief of Staff. Having remained largely apolitical during his military career, if always a staunch conservative, Hindenburg was lured into politics in 1919 when he stood as an independent, Anti-Republican, candidate for the Presidency and shockingly triumphed. Hindenburg’s victory allowed the long awaited triumph of the Right over the Republic to take place the following year – with Hindenburg retained as Head of State until 1925 as Regent of the newly reconstituted German Empire. Adopting a monarchical approach to the Regency he remained ‘above politics’ (in theory at least) before giving the 1925 coup his tacit consent by wilfully surrendering his position as Head of State to Wilhelm II in the aftermath of the seizure of power by his old comrades in the army. A Post-War hero for the Anti-Republican Right, left untarnished by significant participation in avowedly dictatorial regimes of 1897-98 and 1925-28 yet with Anti-Democratic credentials still strong enough to attract Right-wing Radicals. His funeral in 1933 drew crowds in Berlin almost twice the size of those who had greeted the declaration of the Second Republic five years before.

Gustav Stresemann

Born: Brandenburg

Lived: 1878-1947

Leader of German National People’s Party: 1913-1924

Leader of German National Liberal Party: 1924-1935

Chancellor: 1919-1920 and 1928

President: 1928-1933

Franz von Papen

Born: Westphalia

Lived: 1879-1964

Leader of German Centre Party (Monarchist): 1919-1920

Leader of German Centre Party: 1920-1925

Chancellor: 1920-1925

Just as one part of the Conservative tradition embraced National Liberalism and the Republic after 1928, another part retained an Anti-Republican character and instead shifted its loyalty from the House of Hohenzollern to the House of Habsburg. Although Karlist Centrism would always remain a primarily Southern, and especially Austrian, vocation; from the 1920s growing numbers of old-DNVP supporters would turn towards the old party of the Centre founded in the image of its first leader – Franz von Papen. Having been the man to bring down the First Republic, Papen refounded the Centrist movement on a plane upon which it could compete as a legitimate inheritor of the Conservative, as well as Centrist traditions.

Socialism

Variants: Orthodox Social Democracy (19th century Marxism), Communism, Social Democracy, Democratic SocialismMajor Parties: Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) (Post-War), Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED)

Minor Parties: Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) (Pre-War) Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), Communist Party of Germany (KPD)

For German Socialism the period of 1861-1928 was one of a slow and gradual rise. No other political tradition came under such virulent attack during the period, and no other political tradition came so close to be totally extinguished. Yet, for all that, the Socialists can identify a more clear march forward in their strength through the period than any other group. Socialism first began to emerge in Germany as a force to be reckoned with in the decades after the 1848 Revolutions, the onset of capitalist developed produced a social base for the movement in the burgeoning working classes of urban Germany whilst the theories of Karl Marx, amongst less prominent figures, provided a strong ideological backing for a radical labour movement. In 1872, with trade unionism and socialist political parties in a state of semi-legality, two small Socialist groups united to form the Social Democratic Party of Germany. As Orthodox Marxism rapidly became the predominant school of thought within 19th Century German Socialism, the movement was hamstrung by the oppressive Anti-Socialist Laws that left the SPD permanently on the precipice of destruction. After a highly impressive electoral debut in which the party earned a little over 10% of the vote, the Socialist vote went into steep decline through the 1870s and into the 1880s as the Anti-Socialist Laws strangled the movement in the cradle and Christian Democracy stretched out its influence into an apparently leaderless labour movement (the ancestors of the Centrist labour leaders of the period eventually forming the FVP at the end of the century). Even after the repeal of the Anti-Socialist Laws in 1883 the SPD failed to blossom into a major political force, struggling even to exert hegemony over its core constituency of industrial workers in large cities. The Great War was to change everything.

German Socialism was totally transformed by the years 1896-98, with the old society shattered and discredited by the war a wave of revolutions swept Europe and did not spare Germany. The genuine fears of the establishment that the Socialist Left might seize power may have been largely without foundation, but the strength of this myth nonetheless had a major effect on German society. Even in spite of a major split within the Socialist movement between radical revolutionaries (within the USPD and later KPD) and moderates with little taste for social revolution (within the SPD) German Socialism was vastly more influential after the Revolution. In the elections of 1898 and 1903 the combined vote of the SPD and USPD or KPD stood at around 28% and 24% respectively – results unthinkable the decade before. Despite at one point threatening to overtake the SPD as the leading force on the Socialist Left, German Communism collapsed in the late Noughties, allowing Social Democracy to rise as the clear leader of German Socialism – finally absorbing the KPD in 1917 with the formation of the Socialist Unity Party, essentially a rebranded SPD. During the same Republican period Social Democrats established themselves as a party of government, in stark contrast to political pariahs Kaisserreich era SPD the party took part in FVP led governments from 1898-1901 and 1905-1917 (and 1917-1918 as the SED). Whatsmore, during this period the labour movement’s leadership grew gradually more homogenised, at the onset of the 20th century the labour movement was divided into roughly equal Social Democratic, Communist and Populist branches. With the retreat of the FVP from its old radicalism and the death of German Communism, the Social Democrats were able to become totally dominant within the trade union leadership.

The regroupment of the entire movement within the SED allowed German Socialism to take the step forward from a mere supporting role in the ‘progressive’ coalitions of the FVP towards a role of leadership within the Republican movement. The narrow defeat of the SED candidate in the 1919 Presidential election was followed by a renewed alliance with the moderate Republicans in the lead up to the 1920 elections. Although the Left was defeated, the spectacular defeats suffered by the other Republican parties meant that the Republican movement came under heavy Socialist influence. Standing as the strongest poll of opposition to the Right, with its intransigent or openly hostile view of democracy, through the 1920s the SED won by far the largest share of the vote in the 1928 election, coming close to reaching 1/3 of the vote. Although forced to compromise with the National Liberals, the Socialists ensured that Germany would never again come under monarchical rule and secured the rise of the first ever Socialist Chancellor in the form of Otto Braun, the first Chancellor of the Second Republic.

Just like the three other main traditions of German political thought, the Socialists maintain a distinctive reading of the history of the period. Like the Liberals, the Socialists tend to begin their narrative of the period not in the 1860s but in 1848. Rather than a glorious failure, 1848 represented a defining moment when it first became apparent that the aims of the working class were incompatible with the leadership of the bourgeoisie and the dominance of their ideologies as the interests of the two classes for the first time appeared sharply in conflict. As the decades that followed 1848 saw the gradual emergence of an ideology of proletarian character in the form of Marxian Socialism capitalist economic development saw a large urban working class emerge across the country and the proletarianisation of large parts of the economy – wage labour becoming the dominant mode of production. With the potential constituency of Socialism always growing, the working class was seen to have experienced a long and gradual process of political education. Struggles against the old autocracy of the Kaiser and then authoritarian regimes in 1897-98 and 1920-1928 contributed to a political education that, combined with the daily struggles of the labour movement, drove ever greater numbers of workers toward the ideas of Socialism. Inevitably, theorised the Socialists, the overwhelming majority of the population would be won over to Socialism – allowing for the overthrow of the capitalist system and the ushering in of a peaceful, democratic and egalitarian future.

Major Figures:

August Bebel

Born: Rhineland

Lived: 1840-1912

Leader of Social Democratic Party of Germany: 1872-1896

For nearly ¼ of a century August Bebel led the Social Democratic Party from its foundation until the Great War. Whilst his political career came to a decisive end in 1896 and he did not once even approach political power, the titanic legacy he bequeathed to Post-War Socialism was immense. At a time with Far Left thought was extremely fluid, when Marxism competed with various other schools of Revolutionary thought and when the SPD itself was caught between competing pulls towards ultra-leftism and reformism Bebel ensured the party constructed a solid identity built around Orthodox Marxist ideology and mass work. Although the divisions within the Socialist movement, that Bebel arguably helped keep in check during his tenure as leader, eventually came to the fore during the First Republican era both Communist and Social Democratic movements retained a character that was heavily influence by the party of Bebel. Likewise, from the 1920s onwards study of 19th century Social Democracy by those within the milieu of the SED became increasingly common – many seeking to draw lessons from the founding father of the Socialist movement.

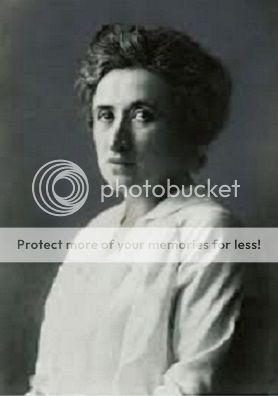

Viktor Adler

Born: Bohemia

Lived: 1852-1923

Leader of Socialist Democratic Workers’ Party of Austria: 1882-1887

Leader of Social Democratic Party of Germany: 1897-1909

Whilst under Bebel’s leadership Social Democracy would survive, under Adler’s it would take another step up. Having been involved in the founding of Austrian Social Democracy (even leading the party during its brief 5 year existence), Adler quickly became one of the first Austrian politicians to have a national impact on the rest of Germany. Taking over the leadership of the SPD after the Great War he participated in the Revolution of 1898 and then proceeded to bring Socialists into government for the first time – participating in the administrations of 1898-1901 and 1905-1909 as a high ranking minister. It was during this early phase of Republican history that the Populist led coalitions were at the height of their reforming zeal, much of which would fall away during the 1910s, allowing Social Democracy to justify itself as the true bearers of the interests of the working class at a time when Communism was able to present a genuine challenge (in 1903 the KPD had come within an inch of overtaking the SPD to become the largest Socialist party in the Reichstag). Although failing to take the SPD from the status of a major political party to a potential leader of the Left, the period of Adler’s leadership was a highly important one for the development of Socialism.

Adam Stegerwald

Born: Bavaria

Lived: 1874-1938

Leader of Free People’s Party: 1898-1920

Chancellor: 1898-1901

President: 1904-1919

Although neither Stegerwald nor the vast majority of his supporters ever claimed to be Socialists, the dominant figure of the First Republic had an inevitably major effect upon German Socialism through virtue of two decades of alliance between the Populists and Socialists, the majority of which was spent in government. During the First Republican era the proper relationship between the Socialist Left and FVP was perhaps the biggest debate in German Socialism. Communists called for the rejection of the Populists, the supporters of Friedrich Ebert (SPD leader 1909-1914) called for total acceptance of the policies of government even if the party should debate with its coalition partners within government. Arthur Crispein (leader of the SPD 1914-1917 and the SED 1917-1919) brought the Socialists into conflict with Stegerwald’s regime at a time when it was shifting alarmingly towards the Right – eventually resulting in a split in the Republican movement that allowed Hindenburg to rise to the Presidency. Finally the party returned to alliance with Stegerwald and his party in the final year of the Republic in a failed attempt to restore the unity of the Republican movement against the Right. Yet, for more than twenty years Adam Stegerwald, more than any undeniably Socialist figure, had shaped the way that Socialist leaders of all shades defined themselves. Degrees of radicalism or disagreements over theoretical concepts came to be subservient to the question over whether one was pro or anti Stegerwald.

Otto Braun

Born: Bavaria

Lived: 1872-1955

Leader of Socialist Unity Party of Germany 1926-1933

Chancellor: 1928-1933

Otto Braun was a lifelong Socialist who slowly but surely worked his way up to the top of Social Democracy. Although hardly appearing to be made in the mould of a great national leader, he oversaw the SED finally achieve power in 1928, not as a minor coalition member, but as the leader of the Republican movement, albeit a leader forced into serious compromises by their newly acquired National Liberal allies. In 1928 Otto Braun became the first ever, but certainly not the last, Socialist to become Chancellor of Germany the stabilisation of the Republic during his five year term helping to solidify its existence. Although he lost both the party leadership and the position of Chancellor in 1933, it was under his leadership that the SED became fully mature as a national leader – ending German Socialism’s own road to modernity.