While marching to Irakleio, the Romaninan Alpine divisions were intercepted by the 5th Greek division in Rethymno. Aircraft was scrambled to bombard the enemy formations. Another two infantry divisions were preparing to land on the shores of Tympary.

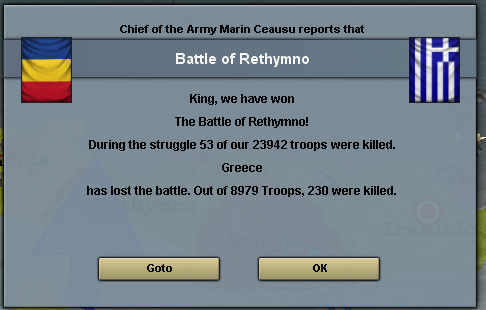

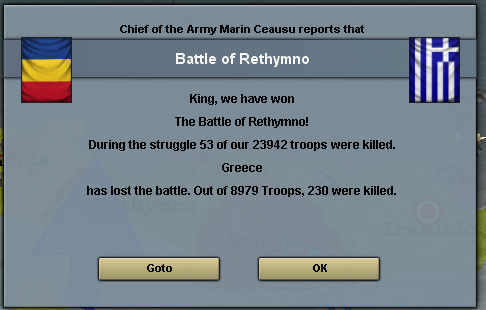

4.10.1938 Battle of Rethymno

4.10.38 Forces distribution

Outnumbered, the Greek division panicked and deserted on 5th October the frontline before due reinforcements could arrive.

5.10.38 Battle results

Later that day the other two divisions tried under intense air fire in an atmosphere of chaos on 5. and 6.10.38 to take defensive positions but failed, retreating hastingly to Irakleio.

Realizing too late that another invasion force had landed in Tympaki the desperate officer corpse itself marched on the province to throw back the Romanians into the Sea, but they stood no chance, being outnumbered by 13 to one.

6.10.1938 Battle of Tympaki

The disastrous counteroffensive mounted by the Greek generals was a masterpiece of incompetence. By the 11.10.1938 all the Greek units were on the run, closely followed by the Romanian divisions on the roads to Irakleio.

11.10.38 Race to Irakleio

On the 18 October the Romanian troops entered Irakleion almost unopposed. The rebel Greek generals signed the capitulation and the next day the annexation of Greece was proclaimed.

19 October, Annexation of Greece

The Romanian Government was unsure as to what to do in Greece. No one in Bucharest wanted to keep Greece occupied, but releasing the country posed a host of problems.

Now, with the Greek army in tatters, Italy would probably be quick to attack and invade the country itself, given the inflammatory language of Mussolini and his fascist Party regarding Italian claims of hegemony in Eastern Mediterranean and of reviving the glory of ancient Rome. On the other hand, the Greek King George II, who took refuge in Bucharest before the Romanian invasion, was a too weak figure to represent any insurance for a stable Greek government and against foreign intervention.

At this point in time the Greek society was deeply fractured, with two strong far right and far right extremes vying for power. The democratic parties were unpopular also due to country’s mismanagement in the past and incapacity to defend the democratic order. Any of the two main alternatives to power in the case of Romanian retreat would almost surely draw major powers (Italy/Axis or USSR/Comintern) in Greece, to fill the power vacuum and implicitly threaten Romanian security.

The diplomatic follow-up from the Greek affair weighted heavy on the Romanian leadership. The Soviet Union almost declared war, Italy became yet again very hostile to Romania, seeing thwarted its hegemonial masterplan in Southern Europe and being rejected the claim on Crete. Germany was less interested in Greece, but is was expected to use this liability to further its interests against Romanias’. The Allies asked for the independence of Greece and building a unity government under Prime Minister Metaxas, but Romania rejected it as too risky. Romania’s foreign ties to the Allies have been since strained durably.

The aim of the Romanian administration in Athens was thus set to build a collaboration Government with moderate Greek political figures and parties, with the longer term goal to liberate the country in a more stable international configuration.

The next task of the Romanian Government was to improve the administration regime in the occupied territories, so that the revolt risks would be eliminated. It was decided to increase the creation of MP divisions, despite the downside of draining some of the the MP for the regular army units for the next year or two. The surfice needed to pacify is more then the original Romanian territory, which creates a certain vulnerability for the nation. At the end of the day a nation has to trade off some vulnerabilities for the others.

20.10.1938 Revolt risk across Romania

On the 21.10.1938 the Romanian cavalry divisions reached the Croat militias and routed them after a short-lived confrontation.

21.10.1938 Croat revolt ended

With the Greek chapter over, we will move to the Treaty of Munich, which bore huge consequences for the future of the region and of the WWII. Romania had little involvement in that episode, but its reverberations on the security architecture of Romania was immense.

4.10.1938 Battle of Rethymno

4.10.38 Forces distribution

Outnumbered, the Greek division panicked and deserted on 5th October the frontline before due reinforcements could arrive.

5.10.38 Battle results

Later that day the other two divisions tried under intense air fire in an atmosphere of chaos on 5. and 6.10.38 to take defensive positions but failed, retreating hastingly to Irakleio.

Realizing too late that another invasion force had landed in Tympaki the desperate officer corpse itself marched on the province to throw back the Romanians into the Sea, but they stood no chance, being outnumbered by 13 to one.

6.10.1938 Battle of Tympaki

The disastrous counteroffensive mounted by the Greek generals was a masterpiece of incompetence. By the 11.10.1938 all the Greek units were on the run, closely followed by the Romanian divisions on the roads to Irakleio.

11.10.38 Race to Irakleio

On the 18 October the Romanian troops entered Irakleion almost unopposed. The rebel Greek generals signed the capitulation and the next day the annexation of Greece was proclaimed.

19 October, Annexation of Greece

The Romanian Government was unsure as to what to do in Greece. No one in Bucharest wanted to keep Greece occupied, but releasing the country posed a host of problems.

Now, with the Greek army in tatters, Italy would probably be quick to attack and invade the country itself, given the inflammatory language of Mussolini and his fascist Party regarding Italian claims of hegemony in Eastern Mediterranean and of reviving the glory of ancient Rome. On the other hand, the Greek King George II, who took refuge in Bucharest before the Romanian invasion, was a too weak figure to represent any insurance for a stable Greek government and against foreign intervention.

At this point in time the Greek society was deeply fractured, with two strong far right and far right extremes vying for power. The democratic parties were unpopular also due to country’s mismanagement in the past and incapacity to defend the democratic order. Any of the two main alternatives to power in the case of Romanian retreat would almost surely draw major powers (Italy/Axis or USSR/Comintern) in Greece, to fill the power vacuum and implicitly threaten Romanian security.

The diplomatic follow-up from the Greek affair weighted heavy on the Romanian leadership. The Soviet Union almost declared war, Italy became yet again very hostile to Romania, seeing thwarted its hegemonial masterplan in Southern Europe and being rejected the claim on Crete. Germany was less interested in Greece, but is was expected to use this liability to further its interests against Romanias’. The Allies asked for the independence of Greece and building a unity government under Prime Minister Metaxas, but Romania rejected it as too risky. Romania’s foreign ties to the Allies have been since strained durably.

The aim of the Romanian administration in Athens was thus set to build a collaboration Government with moderate Greek political figures and parties, with the longer term goal to liberate the country in a more stable international configuration.

The next task of the Romanian Government was to improve the administration regime in the occupied territories, so that the revolt risks would be eliminated. It was decided to increase the creation of MP divisions, despite the downside of draining some of the the MP for the regular army units for the next year or two. The surfice needed to pacify is more then the original Romanian territory, which creates a certain vulnerability for the nation. At the end of the day a nation has to trade off some vulnerabilities for the others.

20.10.1938 Revolt risk across Romania

On the 21.10.1938 the Romanian cavalry divisions reached the Croat militias and routed them after a short-lived confrontation.

21.10.1938 Croat revolt ended

With the Greek chapter over, we will move to the Treaty of Munich, which bore huge consequences for the future of the region and of the WWII. Romania had little involvement in that episode, but its reverberations on the security architecture of Romania was immense.

Last edited: