A History of the Second Roman Empire: The Imperial Years

~~~~~~~~~~

Chapter II: The Idle Years and the War of the Po

Many historians of these times often point to the New Year’s Union of 1451 as the start of a spontaneous transformation from dithering Papal rule to an active, expansionist Second Roman Empire. The only problem with this view is that it is simply not true. The acquisition of Constantinople did not spark a sudden revolution in centuries-old Papal, Italian, or Greek ruling circles, nor did Pope Nicolaus V experience a sudden epiphany that compelled him to expand his borders across the face of the earth in the name of empire. Quite the contrary, for the next decade after Eugenius IV and John VIII worked out their unexpected agreement on New Year's Day, little of actual note really happened.

Not only that, but little truly happened in terms of the changes themselves. True, Constantinople was now a territory under the dominion and ownership of the Pope in Rome, but that was a mere technicality. Constantinople remained Greek, and any attempt to impose Italian, Western European, or even Papal governance would have likely met with disastrous riots, uprisings, and rebellions in and around the city. Eugenius IV understood further that logistics was also a critical deterrent. Hundreds of miles away from the Italian peninsula, Constantinople was comparatively too isolated to be properly governed from Rome, or defended from internal revolts. As a result, life went on virtually as it always had in Constantinople. A small contingent of infantry, five thousand in total, was sent to the city in mid-summer in 1441, and Roman and Catholic officials often journeyed to the city to establish some nominal degree of Papal hegemony, but by and large, the city was left to govern itself. And so long as the tax revenues that used to go to the Emperor went to Rome, and Catholic envoys were not lynched on sight, both parties preferred it that way.

Nor was there any sort of revolution in the way in which the Papacy's Italian acquisitions were governed. Indeed, one of the major reasons in which so large an amount of territory could be so peacefully gained in so short a time was the Papacy's refusal to, or perhaps inability to, interfere with local land owners and nobility. The peace was kept by the enlarged Papal armies and navy, taxes were collected diligently, and life went on as it always had. That the peasants' ultimate master lived in Rome, Naples, or Milan made little difference to them.

But that is not to say Constantinople's sudden change in ownership was completely unimportant. Far from it. The New Year's Union is the integral catalyst for what would propel the Papal States in a new and completely unexpected direction. The process was evolutionary, not revolutionary. It is the first of many milestones on the road to empire.

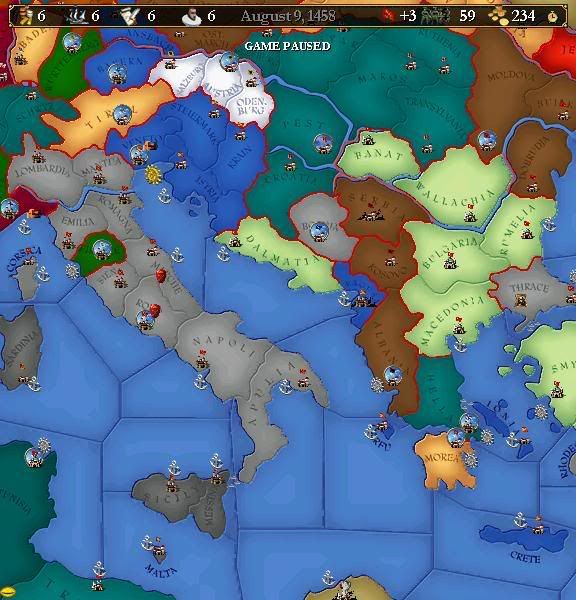

Beyond the rather uninspired view most Papal officials and clergy took toward the new land gains, there was a simple matter of a complete lack of any new, viable prospects that prevented a continued expansion of the Papal domain. In all, the Papal forces in Italy were approximately 25,000 strong, equally divided between foot and cavalry. 16,000 were stationed along the Po River, the rest in Apulia. In the north, the "Northern Alliance," so-called by Eugenius, of Venice, Austria, Tyrol, and Styria dominated the region, handily outnumbering the Army of the Holy Cross. To move the Apulian "Legion of Holy Justice" north would expose the southern provinces to Aragonese forces based in Sicily. The Spanish kingdom still resented the Papal destruction of the kingdom of Naples, which Aragon had significant ties to. And in the east, the Turkish armies, virtual hordes in size, would prove too much for Papal forces.

Sensibly realizing that war was simply not a viable move, Eugenius IV focused his efforts instead on paying off the national debt that had accumulated during the repeated wars of the 1430s. A rather bizarre insistence on paying off the debt in a single lump sum rather than in manageable monthly or annual payments stymied the effort, and by 1449, the debt remained in place, despite the Papacy having amassed large sums in its treasuries. Pope Eugenius IV had died in February of 1447, succeeded by the new Pope, Nicolaus V, born Tommaso Parentucelli. His selection by the college of cardinals showed how wide-spread the belief in continued peace was within the kingdom, as Nicolaus V, as the new Pope's talents lay in administration, diplomacy, and culture, not in the army.

After Eugenius IV's death, Nicolaus inherited a crisis that had been festering since 1443. In that years, Corsican nobles, disgusted with continued Genoan mismanagement incited rebellion on the Mediterranean island. After overthrowing the Genoan garrison, the council of nobles appealed to Eugenius IV for assistance, offering their loyalty and the island for protection, citing the old Donation of Pepin that had given Corsica to the Papal States, which had subsequently been sold to Genoa. Although allied with the small Italian kingdom, Eugenius sided with the nobles, resurrecting defunct claims to the island. The fallout culminated with Genoa being banned from her alliance with the Papal States and Provence and aligning herself with the "Northern Alliance."

But relations had still been festering since then, and many within the States, encouraged by the chronic rebellion on Corsica, demanded that Eugenius, and now Nicolaus, take military action. To do so would be military suicide, of course, and Nicolaus knew it. But pressure for a new war from this developing minority of vocal opponents within the kingdom had reached a critical point after the Jubilee of 1450, and in 1451, Nicolaus caved to pressure, ordering up another thirteen thousand soldiers: seven thousand foot, and the rest cavalry.

There were three options: to rise to the aid of the Corsican rebels, to attack the Ottoman Turks' Balkan holdings, or invade Sicily. Nicolaus favored a war against the new Turk Sultan Mehmed II, who was involved in a war in Asia Minor against Karaman, and whose European provinces would be vulnerable with access through Constantinople blocked off by the Papal fleet. But in July, 1452, war broke out between the "Northern Alliance" and the kingdoms of Hungary and Poland, having grown increasingly troubled by the alliance's expanding influence, power, and confidence to employ both.

With northern Italy suddenly stripped of its garrisoning armies, an opportunity had at last presented itself to diminish the potency of the allied kingdoms. On 30 November 1452, the Papal States and Provence declared war upon Genoa, drawing Venice, Austria, Tyrol, and Styria into the conflict. While the Army of the Holy Cross marched on Genoa from Parma, the new "Legion of Righteousness," under General Serra, struck northwest toward Milan, crossing the Po with no resistance. Under the command of General Lomellini, the Papal army met the Genoan army of approximately eight thousand foot just outside the city on 18 January, destroying the only Allied army south of the Alps and west of Venice. Both Genoa and Milan were besieged, while Provence blockaded Corsica and sent contingents to aid in the investment of Genoa.

As spring and the sieges progressed, Genoan armies, finally reacting to the sudden shift in the strategic situation, performed an about face, rushing back to the defense of their kingdom by way of Venice southwest to Parma, where the seventeen thousand strong army began its siege. Plans for a summer invasion of Corsica with the Apulian "Legion of Holy Justice" – Aragon having stripped Sicily of troops for war in the Iberian peninsula – were suddenly cut short when a Venetian fleet encountered the transport flotilla in the Gulf of Taranto, obliterating the fleet in a stunning battle on 25 July.

This news came along with the announcement a month earlier that Venice had concluded a peace treaty, giving Hungary generous terms for peace in order to deal with the crisis in the south. For the Papacy, this meant that countless thousand veteran soldiers would be on their way south to destroy the treacherous Nicolaus’ armies. With the sieges dragging on, the Pope only possessed a small force of eight thousand marching from Apulia available to him under the command of a General Cotta. The legion established itself in Ferrara to counter whatever the Venetians may send south.

Cotta did not need to wait long. A Venetian army of almost 25,000 and a smaller contingent of Tyrolean troops appeared in September, intent on breaking the Legion of Holy Justice and assaulting Ravenna, and in so doing separating Rome from her armies. The Venetians attempted to cross the Po at Ferrara and battle was met on 5 October. What should perhaps have been the end of Papal ambitions in northern Italy quickly became an unmitigated triumph. Their numbers neutralized by the river, the Venetians were cut down in droves as they attempted to cross. By the afternoon, exhausted from hours of futile river assaults, the Venetians had only managed to gain a small foothold on the southern bank of the river, in which most of the army was concentrated. Sensing an opportunity, Cotta ordered a massive counterattack with his entire army. Packed tightly together on the southern bank, the Venetian army panicked in the face of the devastating cavalry and infantry charge. Within moments, the army disintegrated into complete chaos, as many drowning in the river as were actually killed by Cotta’s men. The rest, approximately ten thousand, surrendered. The Battle of Ferrara was over in a miraculous Papal triumph.

With the north suddenly cleared of enemy resistance, Cotta marched to assist in the siege of Milan, which finally surrendered on the 20th. With no real opposition in the way, Cotta took overall command of the Legions and moved north, hoping to take Innsbruck and forcing Tyrol out of the war. Weather and the threat of encirclement forced him back. In February 1454, Cotta finally marched eastward, surrounding Mantua, Verona, and Padua. The Tyrolean forces, in the meantime, had slipped through and besieged Ravenna.

A general lull in the conflict gave the appearance of a stalemate. The siege of Genoa was dragging on, the Genoan armies dominated Emilia, and Cotta’s legions were busy near Venice. In August, however, Nicolaus displayed his diplomatic skill by managing to persuade Tuscany to join the alliance with the States and Provence. Having fought a long war with the “Northern Alliance” alongside Bavarian in the 1440s, Tuscany was eager to curtail the alliance’s inordinate power, preferring an Italy dominated by Nicolaus V, rather than some distant Austrian emperor. Tuscany was blessed with a substantial army, and perhaps the most technologically advanced force west of Constantinople.

With Tuscany entering the fray, the Austrian Emperor Frederick V, determined not to have northern Italy lost and his alliance shattered, commanded his forces across the Alps and into Lombardy. Almost equal in size to the Venetian army destroyed in the Battle of Ferrara, the imperial Austrian force threatened to turn the tide against the Papal forces.

In October and December respectively, Genoa and Mantua fell to the Pope’s armies. All that prevented Nicolaus V putting an end to the war on terms favorable to the States was the Austrian army now outside Milan. Through tenuous lines of communication between Genoa and Mantua – between the Genoans in Parma and the Austrians in Milan, a bold and risky plan was devised between Lomellini and Cotta.

Just after the turn of the new year, Lomellini marched from Genoa directly toward the Austrians, leaving a contingent of Tuscan and Provencal troops to hold off the army in Emilia, moving slowly enough to draw the Austrians’ attention. Days later, Cotta raced from northward from Mantua, cutting west along the Alps and dispatching several Austrian garrisons in short order before swerving south toward Milan. Suddenly realizing they had been surrounded, the Austrian general, an Italian-born

condottiere named Giustani, abandoned the siege of Milan and rushed north in the hopes of breaking out of the trap. A series of running battles commenced on 26 January, with Lomellini doggedly attacking the Austrian rearguard while Cotta maneuvered into Giustani’s path.

Finally, on 3 February, Giustani was cornered and Lomellini and Cotta converged for the kill. Despite a desperate defense, the Italians overran the Austrian positions within a few hours. Only six thousand Austrians escaped north into the Alpine passes, the rest casualties to the latest Papal triumph.

The series of battles collectively called the Battle of Lombardy broke the back of the last major “Northern Alliance” effort of the war. Combined with news of Tuscan troops marching on the Tyrolean army at Ravenna, Emperor Frederick V concluded that the war had been lost. After consulting with the Venetian Francesco Foscari, Frederick sent envoys to Nicolaus to discuss a peace treaty. Nicolaus was happy to oblige. The two leaders met along with delegates from all the other participants, including the “governor” of Constantinople, Constantine XI, in Venice, the Legion of Righteousness hovering menacingly close in Padua

The resulting Treaty of Venice signed on 5 March, 1455, was a colossal success for Pope Nicolaus V. The Papal States received Lombardy, Mantua, and Corsica, as well as a substantial sum of gold for damages inflicted on the Italian countryside in exchange for remissions from various church obligations for the next several years. Genoa too would remain a part of the “Northern Alliance,” but separated now as it was, this was a mere token gesture on Nicolaus’ part to assuage fears of the nation’s annexation. Sadly, Nicolaus did not live long after his triumphant victory, dying on the 20th of natural causes. In his place, Pope Calixtus III was elected as a compromise candidate. In the years of war, the once minority “war hawks” of the States had gained in strength and boldness, but not enough to override the “Old Guard” of traditionalists and local interest groups. Calixtus III, Alfonso de Borja his birth name, was both an able administrator and leader, to some extent appealing to all factions within the College.

The appealing compromise was not to last, however. Calixtus III was far too old to be expected to reign for long. His reign’s most notable event was a scandal that erupted in Rome when a diplomat from Aragon, with which Calixtus had worked diligently to smooth over relations with before being raised to the papal chair. Details are scarce, but an argument seemed to erupt over the Pope’s bull of 29 June 1456, which urged for a unified effort to drive the Turks from the Balkans that ended up insulting both parties. The misunderstanding did not degenerate further due to Calixtus’ ties with Aragon, but established a tension that would not be soon forgotten. Barely three years after the beginning of his reign, Pope Calixtus III died in his sleep.

Like always, the cardinals assembled in Rome to choose the next Pope. After furious backroom negotiations, a new successor was elected, Pope Pius II. No one, not even the newly elected Pope, could possibly predict what had just been set into motion.