Vive L'Empereur: The Third French Empire - a National France Kaiserreich AAR

- Thread starter Antonine

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Le Chant du Départ?

It's a more "imperial" music.

It was used during the first empire (and it's pretty beautiful) so why not ?

After Research:

La question de l'hymne du Premier Empire

Le "Chant du Départ" a été retenu comme hymne du 1er Empire. La page anglophone de cet article donne la source de cette affirmation : "Le Chant du Départ, Fondation Napoléon, 2008, retrieved 16 May 2012". On peut lire en effet sur le site de la fondation napoléon, à la page ,le propos suivant : "Commentaires : Appelé le "frère de La Marseillaise" par les soldats de l'an II, le Chant du Départ (que Napoléon préférait à La Marseillaise) est devenu l'hymne national du Premier Empire." Malheureusement, cette référence (sans qu'un nom d'auteur de l'article n'apparaisse...) est en contradiction avec le Dictionnaire Napoléon, qui constitue une référence majeure dans le domaine de cet empire. Ce dictionnaire indique à l'article "Hymne" que l'hymne officieux de cet empire était "Veillons au salut de l'empire" (sans majuscule au "e" d'empire : il s'agit de empire au sens : territoire de la patrie ; cf. article Wikipedia de ce chant), lui-même autre chant révolutionnaire. Il semble en fait, au travers du terme "officieux", qu'il n'y ait pas eu de choix explicite par les autorités impériales quant à une musique ou un chant privilégié pour les manifestations nationales : le "chant du départ", "Veillons au salut de l'empire" ou la "marche consulaire" étaient utilisés de manière variée selon les circonstances (cf. article "Hymne" du Dictionnaire Napoléon, l'auteur de l'article étant Jean Tulard, directeur du Dictionnaire). Il apparait donc plus juste de ne pas indiquer d'hymne pour cet article, qui - par ailleurs - mérite d'être absolument refondu, réécrit, etc. pour être juste et équilibré... -

Veillons au Salut de l'Empire was composed 9 years before the Empire (in fact the Empire it talks about is the Republic but you can play on the ambiguity quite easily  )

)

Well I think an earlier update gave the anthem as Partant pour la Syrie as I think that was the anthem of Vichy France so it fits as the anthem for National France. Whether it's since been replaced is something I haven't really thought about.

I'm so sorry for the delay with an update - I need to do a bit of modding to finish it and unfortunately I've got coursework due next Tuesday which is taking up pretty much all of my time since I'm deeply stuck on it

I'm so sorry for the delay with an update - I need to do a bit of modding to finish it and unfortunately I've got coursework due next Tuesday which is taking up pretty much all of my time since I'm deeply stuck on it

- 2

Incidentally, does anyone know if there's a way to get a copy of DH 1.02 from somewhere? This AAR would go much quicker if I could transfer the savegame from my ancient and crumbling laptop to my new computer

If using steam, yes.Does a fresh install automatically update to 1.03?

If you're downloading from steam, I believe there is an option which lets you choose previous betas.

I'm very sorry to say that the update won't happen tonight after all (I'm very close to finishing it but it's nearly 3am and I still have to upload the screenshots) so it will come tomorrow instead :/

- 2

Can't you just copy the installation folder over to another computer? Paradox games have no DRM and AFAIK the installation is usually not customized to your specific computer.Incidentally, does anyone know if there's a way to get a copy of DH 1.02 from somewhere? This AAR would go much quicker if I could transfer the savegame from my ancient and crumbling laptop to my new computer

The Treaty of Bruxelles - Part I

As 1954 dawned it had become blatantly obvious that the armistice in Europe could not endure any longer - prolonged for years to give France the opportunity to consolidate its gains, it was now fraying at the seams. With the absence of a final agreement on the future of Europe discontent was rising amongst civilians living under military occupation and this had already bubbled over into outright attempts at insurrection in Glasgow in Scotland and in Liege in Wallonia.

While these insurrections had been swiftly crushed and the instigators either imprisoned or executed, it was clear that something had to give.

So it was that New Year’s Day 1954 would see heads of state and representatives from across Europe to a conference in Bruxelles where the League of Nations would put the finishing details to the carve up of power and influence which they had already agreed in principle. The first half of the resulting Treaty of Bruxelles would utterly redraw the map of Europe.

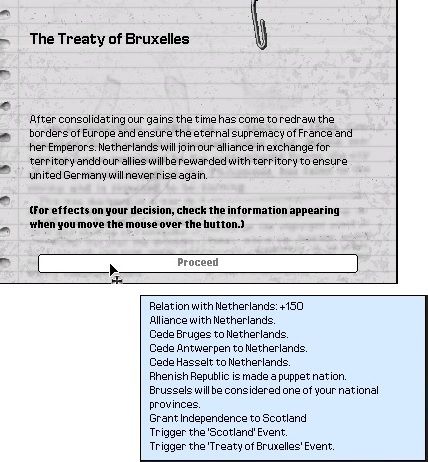

To the surprise of many international observers (and the utter lack of surprise of many others), one chapter of the treaty saw the Netherlands join the League of Nations in exchange for Flemmish speaking Flanders - minus the bilingual city of Bruxelles and its hinterland - and the East Frisia peninsula from the former German Empire. In the process Dutch Indonesia was also brought into the fold of the League, giving France access to much coveted naval bases in the region.

While there were many voices in the Netherlands who warned of sleepwalking into becoming another Batavian Republic, in truth the Dutch government had little choice. Left outside of the League’s trading arrangements it faced severe economic decline without League membership and the addition of territorial inducements made the prospect of membership too tempting to resist.

But the loss of East Frisia was merely the beginning of the carve-up of Germany - a deliberate process to ensure that a united German nation would never threaten the peace in Europe again.

In the north the Kingdom of Denmark saw Otto von Bismarck’s work undone and the return of the entirety of Schleswig-Holstein along with Mecklenburg, Hamburg and Bremen. While this “Greater Denmark” was now marginally more German than Danish, the economic devastation to the German speaking areas within it from the war combined with the decentralisation of the Danish state and the cultural influence of the Danish monarchy to ensure that the country would develop considerable national cohesion over the subsequent twenty years. In particular, the role of Danish companies in the post-war economic recovery, as well as prestige infrastructure projects like the re-opening of the rechristened Kiel Canal, would be vital in ensuring that the large German population became largely convinced that separation from Denmark would do them more harm than good.

Bavaria-Swabia would also gain from the Treaty of Bruxelles. Having already been granted independence as a kingdom in personal union with the Austria it now had its borders confirmed and expanded to include most of Hesse and was formally renamed as the Kingdom of Bavaria-Swabia-Hesse. Already predominantly Catholic with a distinctive culture of its own, it had never taken enthusiastically to the Prussian dominated German Empire and easily adjusted to being part of the extended Austrian Empire. This was undoubtedly helped by significant economic and financial aid provided by the League, via Austria, for reconstruction. Most notably Emperor Otto himself would travel to the ruins of atom-bombed Stuttgart to lay the first stone of Neu-Stuttgart - the new industrial city built in the beautiful Neo-Viennese style which would rise rapidly from the ashes of the old city in the space of just five years.

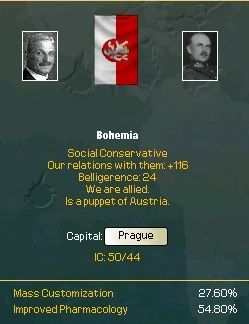

Another nation of the Austrian Empire, Bohemia-Moravia would also gain significantly from the Treaty of Bruxelles. As part of the French efforts to reduce Prussia in size and strength as much as possible, Bohemia was ceded the heavily industrialised regions of Saxony and Lower Silesia, doubling its population.

In the process the ethnic makeup of Bohemia-Moravia, already featuring a significant and influential German minority, was drastically altered. Germans now formed the dominant group in the country with the Czechs reduced to being a minority. This was, in fact, the main motive of the addition of so much territory to Bohemia-Moravia from the perspective of Austria. A potentially rebellious region of the empire had now been inundated with ethnic Germans whose loyalty would inevitably be more towards ethnically German Austria rather than to the various Czech separatist movements.

Yet Prussia was still to suffer further territorial losses and humiliations.

From the French perspective Prussian militarism had been the cause of no fewer than four devastating European wars in the past century and it was Prussia which had been the dominant part of the German Empire - indeed, even to this day, there are many French historians who refer to the three Weltkriegs as being the second to fourth Franco-Prussian wars. Utterly destroying the ability of Prussia to ever threaten France again was therefore the key priority of Napoleon IV and his government.

As a result Prussia also lost considerable territories to Poland under the Treaty of Bruxelles, including the port city of Danzig which formed the main trading port of the “Polish corridor” to the Baltic Sea.

Already industrially devastated by the atomic destruction of Berlin and Koenigsberg, the final territorial losses suffered by Prussia would see it lose three quarters of its population and 80% of its industrial capacity. Flooded with war refugees it was also suffering major housing and food shortages. Even worse, it was legally recognised as being the successor state to the German Empire and was the last country left using the Mark as its currency (the other nations to arise from Germany would adopt the Kroner, the Franc and the Schilling as their currencies respectively) - leading to hyperinflation and economic collapse.

The only reprieve Prussia faced, perversely, came from previous German attempts to dominate the economy of Poland. The Polish railways, electricity supply and many major factories were all owned by Prussian companies. But, as a result of the war, the Polish economy was now almost four times the size of Prussia’s and the Polish arms of these companies were now the only parts still profitable and functioning. It was therefore inevitable that these companies rapidly became Polonised, with assistance from the Polish government, and the economic relationship was reversed.

These effectively Polish companies, albeit with Prussian names, would now play a key effort in reconstruction in Prussia. Through reopening factories they created employment and with generous loans from the Polish government they carried out the rebuilding of Belin and Koenigsberg (in the English brutalist style to keep costs low) which, although restoring them to only a fraction of their previous size and economic importance, allowed much of the refugee population to be rehoused.

But in the process Prussia, already threatened by its border with the Soviets and looking for protection, found itself steadily coming under what would become the Polish sphere of influence. The king of Poland, himself a German nobleman from Saxony, would prove sympathetic to the plight of Prussia, especially so after witnessing firsthand the devastation wrought by the atomic bombs, and his diplomatic influence in Prussia, combined with near total Polish economic dominance, started Prussia on the path to becoming a de facto Polish puppet state.

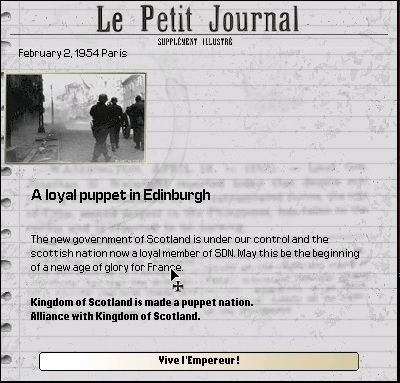

However, while Prussia lost its independence at Bruxelles another nation would gain its independence. Centuries after its disappearance, an independent Scotland would once again appear on the map of Europe.

It reappeared with the blessing of England’s Prime Minister, Enoch Powell, whose personal ideology of English nationalism rejected any attempt at reviving the former United Kingdom of Great Britain in favour of building a New Jerusalem alone in England’s green and pleasant land. While he could have plausibly blocked Scottish independence he instead happily promised to withdraw English soldiers from the portions of Scotland which they occupied in order to allow the re-emergence of the Scottish nation.

The form of this new nation would take many years to be conclusively established but it originated as a burgher republic led by a National Council of aristocrats, military officers and wealthy businessmen who had all gradually regained their prominence in Scotland through the years of the power vacuum which had followed the fall of the Union of Britain.

The views of Enoch Powell on Scottish statehood, however, were far from representative of his government. Winston Churchill, in particular, was a staunch British imperialist and sought the restoration of the United Kingdom as a prelude to a restoration of the British Empire.

The independence of Scotland, while unstoppable, therefore provoked a major crisis in the English unity government which resulted in an ageing Winston Churchill resigning as Chancellor of the Exchequer to form the opposition to the government along with like-minded MPs. This dispute would therefore be the origins of the return to party politics in England with the formation of Enoch Powell’s Christian and dirigiste National Party and Winston Churchill’s liberal, imperialist Unionist Party.

The debate over the ultimate future of the peoples of the British Isles would consequentially be ignited in all three nations of Great Britain and would continue with some vehemence until the consequences of the Quebec Crisis resulted in a generally satisfactory compromise.

The last part of the carve-up of Europe was the fate of the Rhineland. Already ear-marked for the French zone of influence it would be subjected to a prolonged plan to set the border of France not only on the Rhine but beyond it. Formerly part of Prussia it had never sat entirely easily under Prussian rule, not least because its population was predominantly Catholic and because the strength of trade unionism amongst its working class population had led to several bouts of political repression during the region’s time as part of the German Empire. The French therefore considered that they had plenty of material to use to work towards a long term goal of integration with France.

This began with the setup of the semi-independent state of the Rhine Protectorate with a constitution which preserved existing municipal government structures. France assumed a role of a guarantor of, and therefore having veto power over, its constitution which included terms such as obliging the Rhineland to form a customs union with France and to adopt as its currency the Rhenish Franc (which was permanently pegged to the French franc) in order to make it economically dependent on France.

Given that the economy of the Rhineland was in ruins these economic arrangements were actually welcomed by many prominent politicians in the Protectorate as a means of ensuring economic stability and growth. Amongst them was the prominent and long-serving mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer who had a history of flirting with movements for Rhenish separatism from Prussia and who would later become the Directoire of the Protectorate.

Less welcome, however, were the appropriation of major businesses such as Krupp in the name of war reparations, the requirement for all schools to teach in both French and German and the inclusion of the Protectorate’s constitution of a clause which forbade the holding of elected office by anyone who was not proficient in French.

Nevertheless, these initial changes did not prove too onerous and the influx of French investment (paid for by loot from Germany) was to prove especially useful in ensuring reconstruction and economic recovery. The atom-bombed city of Essen was entirely rebuilt in the space of two years, albeit on a smaller scale, but the fact that some of the first families to be moved into the city were French immigrants was a foreshadowing of what was to come.

As 1954 dawned it had become blatantly obvious that the armistice in Europe could not endure any longer - prolonged for years to give France the opportunity to consolidate its gains, it was now fraying at the seams. With the absence of a final agreement on the future of Europe discontent was rising amongst civilians living under military occupation and this had already bubbled over into outright attempts at insurrection in Glasgow in Scotland and in Liege in Wallonia.

While these insurrections had been swiftly crushed and the instigators either imprisoned or executed, it was clear that something had to give.

So it was that New Year’s Day 1954 would see heads of state and representatives from across Europe to a conference in Bruxelles where the League of Nations would put the finishing details to the carve up of power and influence which they had already agreed in principle. The first half of the resulting Treaty of Bruxelles would utterly redraw the map of Europe.

To the surprise of many international observers (and the utter lack of surprise of many others), one chapter of the treaty saw the Netherlands join the League of Nations in exchange for Flemmish speaking Flanders - minus the bilingual city of Bruxelles and its hinterland - and the East Frisia peninsula from the former German Empire. In the process Dutch Indonesia was also brought into the fold of the League, giving France access to much coveted naval bases in the region.

While there were many voices in the Netherlands who warned of sleepwalking into becoming another Batavian Republic, in truth the Dutch government had little choice. Left outside of the League’s trading arrangements it faced severe economic decline without League membership and the addition of territorial inducements made the prospect of membership too tempting to resist.

But the loss of East Frisia was merely the beginning of the carve-up of Germany - a deliberate process to ensure that a united German nation would never threaten the peace in Europe again.

In the north the Kingdom of Denmark saw Otto von Bismarck’s work undone and the return of the entirety of Schleswig-Holstein along with Mecklenburg, Hamburg and Bremen. While this “Greater Denmark” was now marginally more German than Danish, the economic devastation to the German speaking areas within it from the war combined with the decentralisation of the Danish state and the cultural influence of the Danish monarchy to ensure that the country would develop considerable national cohesion over the subsequent twenty years. In particular, the role of Danish companies in the post-war economic recovery, as well as prestige infrastructure projects like the re-opening of the rechristened Kiel Canal, would be vital in ensuring that the large German population became largely convinced that separation from Denmark would do them more harm than good.

Bavaria-Swabia would also gain from the Treaty of Bruxelles. Having already been granted independence as a kingdom in personal union with the Austria it now had its borders confirmed and expanded to include most of Hesse and was formally renamed as the Kingdom of Bavaria-Swabia-Hesse. Already predominantly Catholic with a distinctive culture of its own, it had never taken enthusiastically to the Prussian dominated German Empire and easily adjusted to being part of the extended Austrian Empire. This was undoubtedly helped by significant economic and financial aid provided by the League, via Austria, for reconstruction. Most notably Emperor Otto himself would travel to the ruins of atom-bombed Stuttgart to lay the first stone of Neu-Stuttgart - the new industrial city built in the beautiful Neo-Viennese style which would rise rapidly from the ashes of the old city in the space of just five years.

Another nation of the Austrian Empire, Bohemia-Moravia would also gain significantly from the Treaty of Bruxelles. As part of the French efforts to reduce Prussia in size and strength as much as possible, Bohemia was ceded the heavily industrialised regions of Saxony and Lower Silesia, doubling its population.

In the process the ethnic makeup of Bohemia-Moravia, already featuring a significant and influential German minority, was drastically altered. Germans now formed the dominant group in the country with the Czechs reduced to being a minority. This was, in fact, the main motive of the addition of so much territory to Bohemia-Moravia from the perspective of Austria. A potentially rebellious region of the empire had now been inundated with ethnic Germans whose loyalty would inevitably be more towards ethnically German Austria rather than to the various Czech separatist movements.

Yet Prussia was still to suffer further territorial losses and humiliations.

From the French perspective Prussian militarism had been the cause of no fewer than four devastating European wars in the past century and it was Prussia which had been the dominant part of the German Empire - indeed, even to this day, there are many French historians who refer to the three Weltkriegs as being the second to fourth Franco-Prussian wars. Utterly destroying the ability of Prussia to ever threaten France again was therefore the key priority of Napoleon IV and his government.

As a result Prussia also lost considerable territories to Poland under the Treaty of Bruxelles, including the port city of Danzig which formed the main trading port of the “Polish corridor” to the Baltic Sea.

Already industrially devastated by the atomic destruction of Berlin and Koenigsberg, the final territorial losses suffered by Prussia would see it lose three quarters of its population and 80% of its industrial capacity. Flooded with war refugees it was also suffering major housing and food shortages. Even worse, it was legally recognised as being the successor state to the German Empire and was the last country left using the Mark as its currency (the other nations to arise from Germany would adopt the Kroner, the Franc and the Schilling as their currencies respectively) - leading to hyperinflation and economic collapse.

The only reprieve Prussia faced, perversely, came from previous German attempts to dominate the economy of Poland. The Polish railways, electricity supply and many major factories were all owned by Prussian companies. But, as a result of the war, the Polish economy was now almost four times the size of Prussia’s and the Polish arms of these companies were now the only parts still profitable and functioning. It was therefore inevitable that these companies rapidly became Polonised, with assistance from the Polish government, and the economic relationship was reversed.

These effectively Polish companies, albeit with Prussian names, would now play a key effort in reconstruction in Prussia. Through reopening factories they created employment and with generous loans from the Polish government they carried out the rebuilding of Belin and Koenigsberg (in the English brutalist style to keep costs low) which, although restoring them to only a fraction of their previous size and economic importance, allowed much of the refugee population to be rehoused.

But in the process Prussia, already threatened by its border with the Soviets and looking for protection, found itself steadily coming under what would become the Polish sphere of influence. The king of Poland, himself a German nobleman from Saxony, would prove sympathetic to the plight of Prussia, especially so after witnessing firsthand the devastation wrought by the atomic bombs, and his diplomatic influence in Prussia, combined with near total Polish economic dominance, started Prussia on the path to becoming a de facto Polish puppet state.

However, while Prussia lost its independence at Bruxelles another nation would gain its independence. Centuries after its disappearance, an independent Scotland would once again appear on the map of Europe.

It reappeared with the blessing of England’s Prime Minister, Enoch Powell, whose personal ideology of English nationalism rejected any attempt at reviving the former United Kingdom of Great Britain in favour of building a New Jerusalem alone in England’s green and pleasant land. While he could have plausibly blocked Scottish independence he instead happily promised to withdraw English soldiers from the portions of Scotland which they occupied in order to allow the re-emergence of the Scottish nation.

The form of this new nation would take many years to be conclusively established but it originated as a burgher republic led by a National Council of aristocrats, military officers and wealthy businessmen who had all gradually regained their prominence in Scotland through the years of the power vacuum which had followed the fall of the Union of Britain.

The views of Enoch Powell on Scottish statehood, however, were far from representative of his government. Winston Churchill, in particular, was a staunch British imperialist and sought the restoration of the United Kingdom as a prelude to a restoration of the British Empire.

The independence of Scotland, while unstoppable, therefore provoked a major crisis in the English unity government which resulted in an ageing Winston Churchill resigning as Chancellor of the Exchequer to form the opposition to the government along with like-minded MPs. This dispute would therefore be the origins of the return to party politics in England with the formation of Enoch Powell’s Christian and dirigiste National Party and Winston Churchill’s liberal, imperialist Unionist Party.

The debate over the ultimate future of the peoples of the British Isles would consequentially be ignited in all three nations of Great Britain and would continue with some vehemence until the consequences of the Quebec Crisis resulted in a generally satisfactory compromise.

The last part of the carve-up of Europe was the fate of the Rhineland. Already ear-marked for the French zone of influence it would be subjected to a prolonged plan to set the border of France not only on the Rhine but beyond it. Formerly part of Prussia it had never sat entirely easily under Prussian rule, not least because its population was predominantly Catholic and because the strength of trade unionism amongst its working class population had led to several bouts of political repression during the region’s time as part of the German Empire. The French therefore considered that they had plenty of material to use to work towards a long term goal of integration with France.

This began with the setup of the semi-independent state of the Rhine Protectorate with a constitution which preserved existing municipal government structures. France assumed a role of a guarantor of, and therefore having veto power over, its constitution which included terms such as obliging the Rhineland to form a customs union with France and to adopt as its currency the Rhenish Franc (which was permanently pegged to the French franc) in order to make it economically dependent on France.

Given that the economy of the Rhineland was in ruins these economic arrangements were actually welcomed by many prominent politicians in the Protectorate as a means of ensuring economic stability and growth. Amongst them was the prominent and long-serving mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer who had a history of flirting with movements for Rhenish separatism from Prussia and who would later become the Directoire of the Protectorate.

Less welcome, however, were the appropriation of major businesses such as Krupp in the name of war reparations, the requirement for all schools to teach in both French and German and the inclusion of the Protectorate’s constitution of a clause which forbade the holding of elected office by anyone who was not proficient in French.

Nevertheless, these initial changes did not prove too onerous and the influx of French investment (paid for by loot from Germany) was to prove especially useful in ensuring reconstruction and economic recovery. The atom-bombed city of Essen was entirely rebuilt in the space of two years, albeit on a smaller scale, but the fact that some of the first families to be moved into the city were French immigrants was a foreshadowing of what was to come.

Last edited:

This has to be the best AAR yet. And it's all so plausible to boot too. I love it!

The German population must be devastated by the Nuclear Firestorm. I wonder what the demographics of the region will look like twenty years from now...

- Status

- Not open for further replies.