And so it ends...Great rhapsody.With bitter rivalries,and mostly historic geopolitical outcome.

The Hohenzollern Empire 5: Holy Phoenix - An Empire of Jerusalem Megacampaign in New World Order

- Thread starter zenphoenix

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Here I thought you that a poor spy was one who everyone knew, but apparently fame provides even a spy a level of invulnerability. To fit with the Star Wars memes, if you strike Anne down, she shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.

It also helps that she uses pseudonyms (i.e. Navratilova) and changes her hairstyle.Here I thought you that a poor spy was one who everyone knew, but apparently fame provides even a spy a level of invulnerability. To fit with the Star Wars memes, if you strike Anne down, she shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.

Chapter 427: Peace with Honor

Chancellor Willy Brandt

Willy Brandt was born Herbert Ernst Carl Frahm in Lübeck on 18 December 1913. His mother was Martha Frahm, a single parent, who worked as a cashier for a department store. His father was an accountant from Hamburg whom Brandt never met. As his mother worked six days a week, he was mainly brought up by his mother's stepfather.

After passing his Abitur in 1932 at Johanneum zu Lübeck, he became an apprentice at the shipbroker and ship's agent F. H. Bertling. He joined the "Socialist Youth" in 1929 and the Schweinfurt Faction in 1930. He left the SF to join the more left wing Socialist Workers Party (SAP), which was allied to left-wing movements in China and the Nordics. In 1933, using his connections with the port and its ships, he left the Reich for Kanata to escape Angeloi persecution. It was then that he adopted the pseudonym Willy Brandt to avoid detection by Angeloi agents. Brandt was in the Reich from September to December 1936, disguised as a Kanatan student named Gunnar Gaasland. The real Gunnar Gaasland was married to Gertrud Meyer from Lübeck in a marriage of convenience to protect her from deportation. Meyer had joined Brandt in Kanata in July 1933. In 1938, the Angeloi-controlled Roman government revoked his citizenship, so he applied for Norwegian citizenship. In 1942, he was arrested in Kanata by occupying Angeloi forces, but was not identified as he wore a Kanatan uniform. On his release, he escaped to neutral Tsarist Russia and became a Kanatan citizen, receiving his passport from the Kanatan legation in Stockholm, where he lived until the end of the war. In exile in Kanata and Tsarist Russia, Brandt learned all five major dialects of Norse as well as Finnish and Lithuanian. Brandt spoke the Norwegian Kanatan dialect of Norse fluently (but not the Vinlandic Kanatan dialect), and retained a close relationship with Kanata.

In late 1946, Brandt returned to Berlin, working for the Kanatan government. In 1948, he joined the SPR and became a Roman citizen again, formally adopting the pseudonym Willy Brandt as his legal name.

From 1957 to 1966, Brandt was the mayor of Berlin, leading the city through a period of increased tension which led to the construction of the Berlin Wall. As mayor, he accomplished much in the way of urban development. New hotels, office blocks and flats were constructed, while Charlottenburg Palace (the official residence of the Kaiser in Berlin now that Brandenburg Palace was destroyed) and the old Reichstag building were restored. Sections of the “Stadtring” Autobahn 100 inner city motorway were opened, while a major housing program saw over 20,000 new houses built each year until 1966.

Konrad Adenauer saw Brandt as the wave of the future in the Reich and hoped that Brandt would be his successor, planning to retire at the end of his term and support Brandt’s bid for the chancellery in 1965. However, following the building of the Berlin Wall and the Spiegel Affair, Adenauer resigned, and Brandt was overlooked in favor of the CMU vice chancellor, Erhard.

Brandt became chairman of the SPR in 1964. He was the SPR’s candidate for the chancellery in 1960, 1965, and 1970, but he lost to Adenauer, Erhard, and Scheel in each of those examinations.

Scheel eventually named Brandt his vice-chancellor and was forced to turn over the chancellery to him after the Wassertor scandal forced his resignation.

Soon after becoming chancellor, Brandt set about forming a government. The KRA’s grand social-liberal coalition had collapsed, with the KRA itself suffering massive defections to the CMU and SPR. After three weeks of negotiations, the SPR formed a minority coalition with the CMU and HF which controlled the Reichsrat. The KRA and FMP still controlled the Reichstag, which he feared would prevent him from fully dismantling Scheel’s reforms.

Soon after being sworn in, Brandt made an eight-day trip through the Reich, visiting several major provinces and meeting with religious and political leaders. He also made groundbreaking trips to parts of the eastern bloc, including Dacia and the Soviet Commune, where he met with Brezhnev and Molotov. While in Bucharest, Brandt outlined his New Ostpolitik, or a policy of rapprochement with the Occupied Territories, especially the DDR. He believed that previous chancellors’ policies of sanctions and diplomatic isolation only served to alienate the people of the Occupied Territories and impede reunification. If relations with the east were normalized and sanctions lifted, the Occupied Territories might peacefully drift back into the Roman sphere and speed up the reunification process again.

Zeit magazine named Brandt its Man of the Year for 1972, stating, “Our new chancellor is in effect seeking to end World War II and prevent World War III by bringing about a fresh relationship between East and West. He tries to accept the real situation in Europe, which has lasted for 25 years, but he is also trying to bring about a new reality in his bold approach to the godless equalists.” Later that year, Brandt would receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on normalizing relations.

Next, Brandt tackled the issue of China. The second most powerful nation in the world (although its nuclear arsenal severely lagged behind that of the CSSR) was not a direct enemy of the Reich (ignoring the debacle in Siam), but it wasn’t a friend either. Brandt, working with his Imperial Security Adviser and Foreign Minister Heinrich Kissinger and his Defense Minister Rita Thatcher (who was the first female minister in any Roman cabinet), sought to normalize relations with China. Kissinger and Thatcher helped Brandt bypass the rest of his cabinet and open back channels with sympathetic junta leaders. With relations between the CSSR and China and an all-time low due to Siberian border skirmishes, Brandt sent private word to Chiang through Qiandao, a country friendly to both China and the Reich, that he desired a normalization of relations. A breakthrough soon followed that summer, when Chiang invited a team of Roman table tennis players to visit China and play against top Chinese players (the Romans lost). Brandt followed up by sending Kissinger to China to secretly meet with Chiang’s generals. That July both the Roman and Chinese governments announced that Brandt would visit China in February of 1973. The announcements stunned the world, as such Sino-Roman cooperation was unheard of, even considering their mutual hatred of Soviet equalism.

Some suspected that Brandt was motivated to normalize Sino-Roman relations because he wanted to get China’s support in helping end the war in Siam. In 1972, about 300 Roman soldiers were dying each week in Siam, and the war was broadly unpopular in the Reich, with widespread and sometimes violent antiwar protests taking place regularly (one took place during Scheel’s inauguration and Brandt’s inauguration speech). Opinions concerning the war grew more polarized after Kiesinger instituted a draft lottery in December 1969, which probably contributed to his loss in the examinations at the end of the month. Some 30,000 young men fled to Kanata and Denmark to evade the draft between 1970 and 1973.

Roman jets bomb Chaw Thai positions

The previous Erhard and Scheel administrations had agreed to suspend bombing in exchange for negotiations without any preconditions, but neither side adhered to the agreement. Brandt had concluded that the Siam War could not be won and that the best thing he could do was to secure a ceasefire as soon as possible.

After returning from his trip through the Reich, Brandt began efforts to negotiate a peace with the Thais, sending a personal letter to Pridi Panomyong and other nationalist leaders. Peace talks soon began in Vienna, but no agreements were reached. That summer, Brandt visited Siam, where he met with his commanders and with Regent Sarit Thanarat. Amid protests at home demanding an immediate withdrawal, he ramped up Erhard’s and Kiesinger’s strategy of replacing Roman troops with Siamese troops, known as “Siamization.” He soon instituted phased Roman troop withdrawals but authorized incursions and air raids into Cambodia and Laos to interrupt the Panomyong Trail. More troops were deployed to guard the Siamese supply lines running through Roman-allied Burma. At home, conscription was reduced, with Brandt planning to end it in 1973 and transition to an all-volunteer force.

However, what was most important was Brandt’s domestic policy. At the time Brandt took office, inflation was at 4.7%, its highest rate since the Mitteleimerican War, and rising. The Great Society reforms enacted under Erhard, together with the Siam War costs, caused large budget deficits. Brandt's major economic goal was to reduce inflation; the most obvious means of doing so was to end the war. That however could not be accomplished overnight. The administration adopted a policy of restricting the growth of the money supply to address the inflation problem. As a part of the effort to keep government spending down, Brandt delayed pay raises to federal employees by six months. When the nation's postal workers went on strike, he used the Heer to keep the postal system going. In the end, the government met the postal workers' wage demands, undoing some of the desired budget-balancing. Brandt did little to alter Erhard’s policies through the first year of his chancellery, and the KRA prevented him from doing much to change Scheel’s policies. He also announced temporary wage and price controls, allowed the mark to float against other currencies, and ended the convertibility of the mark into gold.

Brandt's predecessor as chancellor, Kurt Georg Kiesinger, had been an Angeloi (although he didn’t do much) and was a more old-fashioned centrist intellectual. Brandt, having fought the Angeloi and having faced down equalist East Germany during several crises while he was the mayor of Berlin, became a controversial, but credible, figure in several different factions. As the Foreign Minister in Kiesinger's grand coalition cabinet, Brandt laid the foundation stones for his future Neue Ostpolitik. There was a wide public-opinion gap between Kiesinger and Brandt in approval polls.

Both men had come to their own terms with new baby boomer lifestyles. Kiesinger considered them to be "a shameful crowd of long-haired drop-outs who needed a bath and someone to discipline them". On the other hand, Brandt needed a while to get into contact with, and to earn credibility among, the "Ausserparlamentarische Opposition" (APO) ("the extra-parliamentary opposition"). The students questioned Roman society in general, seeking social, legal, and political reforms. Also, the unrest led to a renaissance of right-wing parties in some of the Landers’ Parliaments.

Brandt, however, represented a figure of change, and he followed a course of social, legal, and political reforms. In his first speech before the Diet as the chancellor, Brandt set forth his political course of reforms ending the speech with his famous words, "Wir wollen mehr Meritokratie wagen" (literally: "Let's dare more meritocracy", or more figuratively, "We want to take a chance on more Meritocracy"). This speech made Brandt, as well as the SPR, popular among most of the students and other young Roman baby-boomers who dreamed of a country that would be more open and more colorful than the frugal and still somewhat-authoritarian Ottonian system that had been built after World War II. However, Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik lost him a large part of refugee voters from the Occupied Territories, who had been significantly pro-SPR in the postwar years.

Brandt’s government oversaw the implementation of a broad range of social reforms, and was known as a "Kanzler der inneren Reformen" ('Chancellor of domestic reform'). Within a few years, the education budget rose from 16 billion to 50 billion marks, while one out of every three marks spent by the new government was devoted to welfare purposes, although the KRA blocked many welfare reforms. As noted by the journalist and historian Marion Dönhoff,

People were seized by a completely new feeling about life. A mania for large scale reforms spread like wildfire, affecting schools, universities, the administration, family legislation. In the autumn of 1972 Jürgen Wischnewski of the SPR declared, 'Every week more than three plans for reform come up for decision in cabinet and in the Assembly.'

According to Helmut Schmidt, Brandt’s vice chancellor, Willy Brandt's domestic reform program had accomplished more than any previous program for a comparable period. Levels of social expenditure were increased, with more funds allocated towards housing, transportation, schools, and communication, and substantial federal benefits were provided for farmers. Various measures were introduced to extend health care coverage, while federal aid to sports organizations (especially football) was increased. A number of liberal social reforms were instituted whilst the welfare state was significantly expanded (with total public spending on social programs nearly doubling between 1969 and 1975), with health, housing, and social welfare legislation bringing about welcome improvements, and by 1975 the Reich had one of the most advanced systems of welfare in the world. However, KRA opposition in the Reichstag prevented Brandt from repealing Scheel’s disastrous economic policies, reducing the effectiveness of most of the SPR’s reforms.

Substantial increases were made in social security benefits such as injury and sickness benefits, pensions, unemployment benefits, housing allowances, basic subsistence aid allowances, and family allowances and living allowances. While Brandt was prevented from repealing the economic policies which caused rampant unemployment, he could at least help the unemployed stay afloat until he could do so. During most of Brandt’s term, the majority of benefits increased as a percentage of average net earnings.

In the field of health care, various measures were introduced to improve the quality and availability of health care provision. Free hospital care was introduced for 90 million recipients of social relief, while a contributory medical service for 230 million panel patients was introduced. The reduction of sickness allowance in case of hospitalization was discontinued. That same year, compulsory health insurance was extended to the self-employed.

The Pension Reform Law of 1972 guaranteed all retirees a minimum pension regardless of their contributions and institutionalized the norm that the standard pension (of average earners with forty years of contributions) should not fall below 50% of current gross earnings. The 1972 pension reforms improved eligibility conditions and benefits for nearly every subgroup of the Roman population. According to one study, the 1972 pension reform “enhanced” the reduction of poverty in old age. Voluntary retirement at 63 with no deductions in the level of benefits was introduced, together with the index-linking of war victim's pensions to wage increases. Guaranteed minimum pension benefits for all Romans were introduced.

In education, the Brandt Administration sought to widen educational opportunities for all Romans. The government presided over an increase in the number of teachers, generous public stipends were introduced for students to cover their living costs, and Roman universities were converted from elite schools into mass institutions. The school leaving age was raised to 18, and spending on research and education was increased by nearly 300% between 1972 and 1974. Fees for higher or further education were abolished, while a considerable increase in the number of higher education institutions took place. A much-needed school and college construction program was carried out, together with the introduction of postgraduate support for highly qualified graduates, providing them with the opportunity to earn their doctorates or undertake research studies.

Regarding civil rights, the Brandt Administration introduced a broad range of socially liberal reforms aimed at making the Reich a more open society. Greater legal rights for women were introduced, as exemplified by the standardisation of pensions, divorce laws, regulations governing use of surnames, and the introduction of measures to bring more women into politics (which led to Britannian representative Rita Thatcher becoming the first female minister in the Roman cabinet). The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18, the age of eligibility for political office was lowered to 21, and the age of majority was lowered to 18. The Third Law for the Liberalization of the Penal Code liberalized and protected "the right to political demonstration", while equal rights were granted to illegitimate children that same year. Corporal punishment was banned in schools. A measure was introduced that facilitated the adoption of young children by reducing the minimum age for adoptive parents from 35 to 25.

A number of reforms were also carried out to the armed forces, as characterized by a reduction in basic military training from 18 to 15 months, a reorganization of education and training, and personnel and procurement procedures. Defense Minister Rita Thatcher led the development of the first Joint Service Regulation ZDv 10/1 (Assistance for Innere Fuehrung), which revitalized the concept of Innere Fuehrung while also affirming the value of the “citizen in uniform.” According to one study, as a result of this reform, “a strong civil mindset displaced the formerly dominant military mindset,” and forced the Armed Forces’ elder Junker-dominated generation to accept a new type of soldier envisioned by Thatcher.

A federal environmental program was established, and laws were passed to regulate garbage elimination and air pollution via emission. Matching grants covering 90% of infrastructure development were allocated to local communities, which led to a dramatic increase in the number of public swimming pools and other facilities of consumptive infrastructure throughout the Reich. The federal crime-fighting apparatus was also modernized while a Foreign Tax Act was passed which limited the possibility of tax evasion. In addition, efforts were made to improve the railways and motorways. In 1972, a law was passed setting the maximum lead content at 0.4 grams per liter of gasoline, and in 1973 DDT (a pesticide whose dangerous side-effects were described in Richenza Karlsen’s book Silent Spring) was banned. The Imperial Emissions Control Law, passed in March 1973, provided protection from noxious gases, noise, and air-borne particulate matter.

Under the Brandt Administration, the Reich attained a lower rate of inflation than in other industrialized countries at that time, while a rise in the standard of living took place, helped by the floating and revaluation of the mark. This was characterized by the real incomes of employees increasing more sharply than incomes from entrepreneurial work, with the proportion of employees' incomes in the overall national income rising from 65% to 70% between 1972 and 1975, while the proportion of income from entrepreneurial work and property fell over that same period from just under 35% to 30%. In addition, the percentage of Romans living in poverty (based on various definitions) fell between 1972 and 1975. Unemployment remained high despite these achievements due to the KRA obstructing all attempts to reinstate the industrial subsidies program, although unemployment benefits helped the unemployed maintain a reasonable standard of living.

Environmental policy had not been a significant issue in the 1970 examination; the candidates were rarely asked for their views on the subject. Brandt saw that the first Earth Day in April 1970 presaged a wave of public interest on the subject, and sought to use that to his benefit; in June 1972 he announced the formation of the Environmental Protection Bureau (EPB). Other initiatives included the Clean Air Act, Occupational Safety and Health Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act. Other significant regulatory legislation enacted during Nixon's presidency included the: Noise Control Act (1972), Marine Mammal Protection Act (1972), Consumer Product Safety Act (1972), and the Endangered Species Act (1973).

While applauding Nixon's progressive policy agenda, environmentalists found much to criticize in his record. The administration strongly supported continued funding of the "noise-polluting" supersonic jet program. Additionally, he vetoed the KRA-proposed Clean Water Act, and after the Kaiser overrode the veto, Brandt diverted the funds the KRA had authorized to implement it. While not opposed to the goals of the legislation, Brandt objected to the amount of money to be spent on reaching them, which he deemed excessive.

In addition to economic reform, Brandt also presided over the Roman space program. After a nearly decade-long national effort, the Reich won the race to land astronauts on the moon on 3 January 1969 with the flight of Artemis 11. Despite Brandt being in favor of increased funding, the KRA-dominated Reichstag was unwilling to keep funding for RANA at the high level seen through the 1960s as RANA prepared to send men to the moon. RANA chief administrator Werner von Braun and chief scientific adviser Johann von Neumann drew up ambitious plans for the establishment of a permanent base on the moon by the end of the 1970s and the launch of a manned expedition to Mars as early as 1981. The KRA, however, rejected both proposals, despite Brandt and the Kaiser being in favor. In May 1972 Brandt approved a five-year cooperative program between RANA and the Soviet space program, culminating in the Artemis–Soyuz Test Project in 1975. Although the KRA rejected plans for a moon base and for a manned Mars expedition, it did, however, authorize

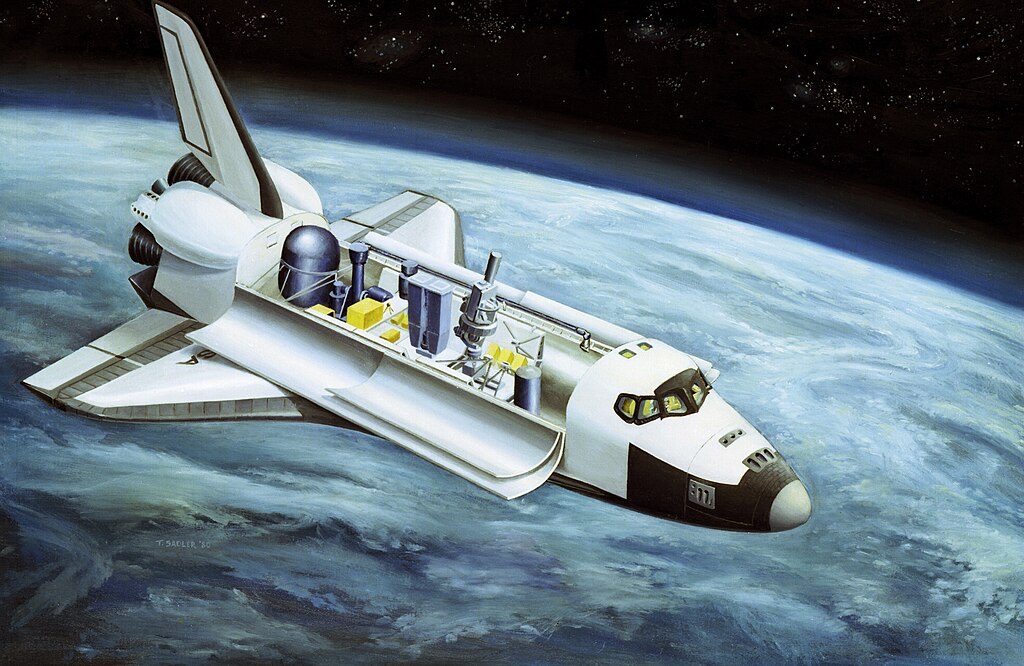

Before the Artemis 11 moon landing, RANA began early studies of space shuttle designs. In 1969, Erhard formed the Space Task Group, chaired by Vice Chancellor (later chancellor) Kurt Georg Kiesinger. This group outlined ambitious post-Artemis missions centered on a large permanently manned space station, a small reusable logistics vehicle that would support it, and ultimately a manned mission to Mars. Smaller goals included a variety of space vehicles for moving spacecraft around in orbit.

Presenting the plans to Erhard, Kiesinger was told that the administration would not commit to a Mars mission, and Erhard limited activity to low Earth orbit for the immediate future. He was then told to select one of the two remaining proposals: a space station and a reusable spacecraft. After some debate between the station and the vehicle, the vehicle was chosen; suitably designed, such a spacecraft could perform some longer-duration missions and thus fill some of the goals of the station, and over the longer run, could help lower the cost of access to space and make the station less expensive.

Concept art for the space shuttle

The goal, as presented by RANA to the Diet, was to provide a much less-expensive means of access to space that would be used by RANA, the Bureau of Defense, and other commercial and scientific users.

During early shuttle development, there was great debate about the optimal shuttle design that best balanced capability, development cost and operating cost. Ultimately the current design was chosen, using a reusable winged orbiter, reusable solid rocket boosters, and an expendable external fuel tank for the orbiter's main engines.

The shuttle program was formally launched on 3 February 1972, when Chancellor Brandt announced that RANA would proceed with the development of a reusable space shuttle system. The stated goals of "transforming the space frontier...into familiar territory, easily accessible for human endeavor" was to be achieved by launching as many as 50 missions per year, with hopes of driving down per-mission costs.

The first orbiter was originally planned to be named Augustin, but a massive write-in campaign from fans of the Startreck television series convinced Bukoleon Palace to change the name to Metternich, after Captain Joseph Franz Kirchner’s starship. Amid great fanfare, Metternich (designated OV-101) would be rolled out on September 17, 1976, and later conducted a successful series of glide-approach and landing tests in 1977 that were the first real validation of the design. All Space Shuttle missions were to be launched from Franz Joseph Space Center.

Meanwhile, Denmark underwent a rare transition in power. Shortly after King Haakon had delivered his New Year's Address to the Nation, he became ill with flu-like symptoms. After two days’ rest, he suffered cardiac arrest and was rushed to the municipal hospital on 3 January. After a brief period of apparent improvement, the King's condition took a negative turn on 31 January, and he died 3 days later, on 3 February, at 7:50 pm surrounded by his immediate family and closest friends, having been unconscious since the previous day.

Following his death, the King's coffin was transported to his home at Amalienborg Palace, where it stood until 18 February, when it was moved to the temple at Hardradasborg Palace. There the King was placed on castrum doloris, a ceremony largely unchanged since introduced at the burial of Aleta I in the 15th century, and the last remaining royal ceremony where the Scandinavian Crown Regalia is used. The King then lay in state for six days until his funeral, during which period the public could pay their last respects.

The funeral took place on 24 February 1972, and was split in two parts. First a brief ceremony was held in the chapel where the king had lain in state, where the High Godi of Copenhagen, Thorfinn Westergaard Madsen said a brief prayer, followed by a hymn, before the coffin was carried out of the temple by members of the Royal Life Guards and placed on a gun carriage for the journey through Copenhagen to Copenhagen Central Station. The gun carriage was pulled by 48 seamen and was escorted by honor guards from the Danish Army, Air Force, and Navy, as well as honor guards from Tsarist Russia, Kanata, Finland, China, and the Reich.

At the Copenhagen Central Station, the coffin was placed in a special railway carriage for the rail journey to Roskilde. The funeral train was pulled by two DSB class E) steam engines. Once in Roskilde, the coffin was pulled through the city by a group of seamen to Roskilde Cathedral where the final ceremony took place. Previous rulers had been interred in the cathedral, but it was the King's wish to be buried outside.

Aleta III of Denmark

His eldest daughter, Aleta, was quickly proclaimed Queen of Denmark, becoming the first female monarch from the House of Estrid since the reign of Aleta II in the early modern period. Originally, the Danish constitution, promulgated in the 1920s after the collapse and partition of Scandinavia, limited the royal succession to men only, but Haakon succeeded in amending the constitution to allow women to be considered in the royal succession.

The Queen’s main tasks as a constitutional monarch were to represent the Kingdom of Denmark abroad and to be a symbol of national unity to the Scandinavian people. She did not have any influence in party politics and did not express any political opinions, although she was responsible for appointing a cabinet and convening the Hogting.

Besides being Queen, Aleta III was also an accomplished painter, whose illustrations were used in the 1975 edition of Tolkien’s Das Ringherr.

While Brandt was busy implementing his reforms (and trying to get around the KRA), the Reich found itself under attack from one of its oldest enemies.

In early 1972, a 38-year-old Jewish cleric named Abraham Hoti from a village in Kosovo went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He also visited family in Mesopotamia, where lots of Jews had settled during the medieval period. Due to a strike by Mesopotamian oil workers in protest of the Siam War, disease containment efforts were somewhat hampered. Koti returned home to Kosovo on 15 February. The next morning, he felt achy and tired but believed it was a result of his long bus ride from the airport. He soon realized he had an infection, but after feeling feverish for two days, he recovered. He thought nothing more of it.

The next month, a thirty-year-old schoolteacher, Latif Mumdzic, also fell ill, though he had no direct contact with Hoti. When he visited a local clinic two days later, the doctors tried to treat him with penicillin, but it had no effect. Mumdzic’s brother took him to a hospital in Cacak, 150 km away, but nobody there could help him either, so he was transferred to a hospital in Belgrade. Doctors there believed that his condition was a result of an adverse reaction to penicillin. The next day, he suffered massive internal bleeding and died.

Although he was now dead, the infection did not die with him. Mumdzic had infected at least 38 people throughout the province, eight of whom would die. A week later, a wave of 140 similar cases would erupt across Kosovo.

Brandt acted quickly and declared martial law in Kosovo within days. Villages and neighborhoods were quarantined, roadblocks were put up, public meetings were banned, and all non-essential travel was prohibited. After Mumdzic’s brother developed a rash, medical authorities finally realized they were dealing with a smallpox epidemic.

By 1972, vaccination for smallpox had long been widely available and the disease was for all intents and purposes eradicated in the Reich, the Nordics, the eastern bloc, and China. The Roman population had been regularly vaccinated against smallpox since the late 18th century, and the last case was reported in 1963, when Tsarist sailors returning from Siam caused a relatively small outbreak. This was the major cause for the initial slow reaction by Roman doctors in 1972, who did not promptly recognize the symptoms of the disease when it started to spread once again.

In October 1970, a Zoroastrian Afghan family went on pilgrimage from Afghanistan, where smallpox was endemic, to Mashhad in Persia, triggering a massive epidemic of smallpox in Persia that would last until September 1972, with disease containment measures hampered by a harsh blizzard which brought the country to a standstill. By late 1971, smallpox-infected devotees on pilgrimage had carried the smallpox from Iran into the Middle East and Turkestan, where Hoti had presumably caught the disease.

The government undertook a massive revaccination program not only in Illyria but also in every other province of the Reich, helped by the World Health Organization. Within two months, almost the entire population had been revaccinated. By mid-May, the spread of the disease had been stopped and things returned to normal. During the epidemic, 175 people had been infected and 35 died. The death toll could have been much higher if Brandt hadn’t acted quickly. He received international praise for his quick thinking and effective handling of the epidemic.

(Ignore the “Dictator Assassinated”)

In the east, the island nation of Qiandao became the latest victim of Paullu-style republicanism when its chancellor, Ma Feng, declared martial law.

Ma Feng, after his successful first term in office, was re-elected chancellor in 1969, becoming the first president of the independent Dominion of Qiandao to achieve a second term. Ma’s opponents blocked the necessary legislation to implement his ambitious plans though. Because of this, optimism faded early in his second term and economic growth slowed. Amidst the rising wave of lawlessness and the threat of an equalist insurgency, Ma declared martial law on April 22, 1972 through Proclamation No. 1081. Ma, ruling by decree, curtailed press freedom and other civil liberties, shut down the Qiandao National Diet and media establishments, and ordered the arrest of opposition leaders and militant activists, including his staunchest critics senators Ai Benghua, Shu Longji, and Diem De Vu. The declaration of martial law was initially well received, given the social turmoil Qiandao was experiencing. Ma claimed that martial law was the prelude to creating a 'New Society' based on new social and political values. A week later, Qiandao called a constitutional convention which wrote a new constitution abolishing the monarchy and declaring the Republic of Qiandao, with Ma as its president for life. All ties with China were severed, and Ma took steps to align with the Reich against protests from Mexico.

Chiang didn’t do much about Qiandao. He didn’t see the islands as that important. He had plenty of islands around Qiandao (which was in all cases too corrupt to oppose him) to use as naval bases, and he was anyways too busy dealing with Southeast Asia. What did draw his interest was the discovery of some Han Dynasty-era imperial tombs, accidentally unearthed by construction workers on 2 May. Inside the tombs were dozens of ancient Chinese writing tablets dating back to the Han Dynasty, containing writings that were previously unknown or presented different or more complete versions of well-known classic texts, among them The Art of War and some of Confucius’s teachings.

On 12 May, President Ma formally petitioned Kaiser Otto to join the Central Powers. While Brandt had his misgivings about letting a republican state into the monarchy-dominated bloc (conveniently overlooking the republican regimes in Mayapan and the UPM that were only overthrown a few years earlier), he signed a treaty of mutual defense but informed Ma that unless he restored a monarchy under any monarch that wasn’t himself, he wouldn’t be able to get access to the Central Powers’ markets or anything more than protection in a defensive war.

In the Nordics, the government of Kanata passed landmark legislation, legalizing the worship of Christianity for the first time since the Pagan Resurgence almost a thousand years ago. From the 1970s there had been a revival of Christianity in the Nordic countries. A farmer and poet named Sveinbjorn Beinteinsson founded the Christian Fellowship organization in 1972, when Christianity was still nominally banned (or at least frowned upon) in Noregr, Denmark, and Tsarist Russia. The Christian Fellowship was granted recognition as a registered religious organization in 1973, when Noregr passed a law recognizing and tolerating the worship of Christianity. Danmark and Tsarist Russia soon followed. Christians would remain a minority in the Nordic countries, but at least their rights would be respected now.

Despite the space shuttle program being officially launched, Werner von Braun continued lobbying the Diet to consider his proposals for a moon base or a Mars mission. The KRA-dominated Reichstag made sure his ideas never got a chance to be considered. In the meantime, the KRA also slashed funding for RANA, declaring that it had “served its purpose” and that it was time to focus on matters at home.

In addition, the oil strike in the Middle East had spread throughout the region, with strike leaders declaring they no longer wanted to provide “fuel for the Siamese slaughterhouse.” The Reich was forced to rely on its reserves and oil produced in the North Sea and Neurhomania, but there were reports that the strike might spread there next. Combined with Scheel’s unilateral withdrawal from the Bretton Woods system and Brandt’s subsequent floating of the mark, this caused an “oil shock,” causing the price of oil to rise to over 5 marks per barrel.

The effects of the strike were immediate. Oil companies were forced to increase payments dramatically, quadrupling the price of oil by 1974 to nearly 12 marks per barrel. Retail gas prices rose from a national average of .385 marks in 1972 to over .551 marks in 1973. Several Lander advised citizens not to put up Christmas lights that holiday season, while others banned lighting altogether. After politicians called for gas to be rationed nationwide, Brandt requested gas stations to voluntarily not sell gas on weekends. About 90% of owners complied, causing long lines of customers at the pump. Concurrent with this strike, coal miners and railroad workers also went on strike, forcing Brandt to ask the people to heat or air condition only one room in their houses at a time. Kanata and many parts of the western Reich banned flying, driving, and boating on Sundays. Tsarist Russia rationed gas and heating oil. The Frisian Lander went as far as to impose harsh prison sentences (several months in jail and a heavy fine) on those who used more than their ration of electricity. A national speed limit of 55 mph (88 km/h) was imposed on all lengths of the Autobahn, which normally had no speed limit. Daylight saving time was implemented for the entire year, forcing many children to travel to school before the sun went up.

The KRA used the oil crisis to justify their slashing of RANA’s budget, claiming that RANA wasted valuable taxpayer money that could better be spent fixing the economy. In his frustration at being ignored and his organization being trampled upon, von Braun retired on 3 June, declaring that his visions for RANA had become incompatible with what RANA was actually doing (and not doing). Von Neumann likewise resigned in protest, taking up a post as head of research and development at Tesla Dynamic until his death on 23 June 1977, just a week after von Braun himself passed away from pancreatic cancer. The KRA didn’t care about von Braun’s and von Neumann’s resignations and simply appointed replacements who were willing to accept the budget cuts.

Over in Japan, Brandt found himself tangled in yet another crisis. Both Japans suffered from a massive crime wave as yakuza gangs and Mexican- and Tawantinsuyuan-funded republican insurgents caused trouble in major cities, especially the economic hubs of Osaka and Edo. The Reich offered to step in to help crack down on the yakuza in Imperial Japan, which provoked diplomatic protests from the Shogunate and the UTR, which saw the Reich as infringing on Japanese sovereignty. Both countries also sent “advisers” to help crack down on the gangs, though only the Shogunate was in a position to do anything. Nevertheless, Brandt was forced to negotiate a treaty with the Shogunate which allowed both the Reich and the Shogunate to equally assist Imperial Japanese law enforcement.

Brandt was so busy dealing with the oil crisis and other events around the world and within his own country that he had no time for the most important issue of them all: Bohemia. By the summer of 1972, most of Bohemia-Moravia had fallen to the combined forces of the CSSR and the Warsaw Pact. All significant resistance outside of Prague had been destroyed. Prague itself was under siege. The last bastions of resistance were in the process of being destroyed. By the morning of 21 July, Dubcek and all of his allies had been captured and flown to Kiev, where they were put under enhanced interrogation by the KGB. On 23 July, Dubcek was forced to sign the “Kiev Protocol,” which demanded the restoration of the original Bohemian government and an end to Dubcek’s reforms. By 26 July a new Bohemian representative to the UN requested the whole issue be removed from the Security Council's agenda, and the Security Council agreed. Shirley Tempel Schwarz, a former child singer and celebrity who had taken up politics, visited Prague to be part of an Athanatoi-organized convoy of vehicles that evacuated Roman citizens and hundreds of Prague civilians from Bohemia.

On 31 July, the last major bastions of resistance in Prague were eliminated, and the city was completely pacified. Bohemia was again firmly under the Soviet heel. Gustav Husak became the new First Secretary of the Equalist Party of Bohemia-Moravia and implemented a policy of “Normalization.” KGB threats forced many Dubcek allies to switch sides or resign, with many of the politicians responsible for helping Dubcek come to power and implement his reforms now condemning him, appointing Husak, and repealing his reforms. Husak purged the Equalist Party of its liberal members, dismissed the professionals and intellectuals who disagreed with him, banned all non-equalist political parties, restored censorship, and ended press and assembly freedoms.

In the Reich, the notoriety of the Soviet forces under Colonel Valentin Varennikov, who reportedly targeted women, children, and elders and bombed churches and historical buildings with impunity, led to him featuring on a cover of Lebens magazine, which named him the “Murderer of Moravia” (“Butcher of Bohemia” didn’t alliterate as well in German). An iconic photo of the Athanatos Anne Frank facing down a line of Soviet tanks while unarmed was also circulated among major newspapers.

As for Dubcek himself, he was expelled from the Party and given a job as a ranger in a remote Slovakian forest, where he could do no harm. He still remained popular among the Bohemian and Slovakian tourists who visited the forests and encountered him, though they were probably confused as to what their former leader was doing as a forest ranger in the middle of nowhere.

Ironically, the economic impact of the invasion so strained the CSSR’s economy that Brezhnev was forced to request a loan from the IMF, just as Khrushchev had been done after Cuba.

As Brandt continued withdrawing Roman troops from Siam, the Chaw Thai went on the offensive, attacking the air base at Lopburi in August. While the attack was easily beaten back, withdrawal continued as scheduled, despite the AKSM showing that it was not ready to fight on its own.

By September, India’s rapidly growing economy had overtaken that of the CSSR itself and closed in on China’s economy. This, combined with the expansion of the Imperial Indian Army to become the largest standing army outside of both the Reich and China, contributed to many in the world starting to see India as no longer just a regional power but rather a superpower, just like the Reich and China. The Big Three empires of China, India, and Rome, which had dominated the world for most of human civilization and especially in the early modern period, were back.

As for the CSSR, nobody considered it a superpower anymore. Such a blow to Soviet prestige kicked off a wave of protests across the Soviet Commune and the Occupied Territories that were brutally suppressed.

In December, the Chinese video game company Dachi released Ping, a landmark video game. Ping is a two-dimensional sports game that simulates table tennis. The player controls an in-game paddle by moving it vertically across the left side of the screen, and can compete against either a computer-controlled opponent or another player controlling a second paddle on the opposing side. Players use the paddles to hit a ball back and forth. The aim is for each player to reach eleven points before the opponent; points are earned when one fails to return the ball to the other. The Ping arcade games manufactured by Dachi would become a great success, launching the video game industry as a lucrative enterprise.

(It should say Ping instead of Pong)

At the end of the year, the Reichsrat convened again for its 1973 session. With the disorganized liberals and progressives still reeling from the aftermath of Wassertor, the KRA and FMP lost even more seats in the upper house, plummeting to a combined total of under 8% of seats, a drop of four percent from last year. The progressives lost almost 3%, dropping to under 5%. The populists and traditionalists also suffered moderate losses. Most surprisingly, the SPR and socialist factions also lost 3.5% of seats, dropping to 21%. The two ideological factions that benefited the most were the conservatives (gaining almost 12% of seats and reclaiming their place as the largest faction in the upper house) and, surprisingly, the equalists, who now shot up to over 7% of seats.

As Brandt began his second year in office, the economy was plagued by a stock market crash and a surge in inflation brought on by the oil crisis. With the legislation authorizing price controls set to expire on April 30, the Reichstag recommended a 90-day freeze on all profits, interest rates, and prices. Brandt re-imposed price controls in June 1973, echoing his 1971 plan, as food prices rose; this time, he focused on agricultural exports and limited the freeze to 60 days. The price controls became unpopular with the public and business people, who saw powerful labor unions as preferable to the price board bureaucracy. Business owners, however, now saw the controls as permanent rather than temporary, and voluntary compliance among small businesses decreased. The controls and the accompanying food shortages—as meat disappeared from grocery stores and farmers drowned chickens rather than sell them at a loss—only fueled more inflation. Despite their failure to rein in inflation, controls were slowly ended, and on April 30 their statutory authorization lapsed. Ultimately, inflation would rise to 12.1% by the end of the year.

The final years of Tawantinsuyuan leader Sabana Anuhi's presidency were marred by political scandals, mainly revolving around the allegations that Anuhi - surrounded by KGB advisors - had turned Tawantinsuyu into a center for Soviet instead of Chinese or Roman operations in South Eimerica, despite Anuhi claiming he was anti-equalist. The nationalization of Roman, Chinese, and other foreign-owned companies and the declaration of a republic led to increased tensions with both the Reich and China. As a result, the Brandt chancellery and the Chinese government organized and inserted secret operatives and exercised economic pressure in Tawantinsuyu, in order to quickly destabilize Anuhi's government. By 1972, the economic progress of Anuhi's first year had been reversed, and the economy was in crisis. The Athanatoi and Jinyiwei reached out to sympathetic members of the Tawantinsuyuan military, which was heavily right-wing and anti-equalist.

On 29 October 1972, a rogue tank regiment surrounded the former royal palace (now Anuhi’s presidential palace) and attempted to depose the president, but he failed. The next month, the national courts complained that the government could not enforce the law, and on 22 November the legislature accused the executive branch of unconstitutional acts (although there was no constitution to begin with) and called on the military to enforce constitutional order.

For months, Anuhi feared calling on the national police, suspecting that they were part of a conspiracy to depose him. He tried appointing a friend as defense minister and commander-in-chief of the army, but after a scandal he was forced to resign both positions, and General Auqui Pirama replaced him. On 24 November, Anuhi condemned the legislature’s actions, calling for the Tawantinsuyuan people to join him in destroying this “threat to the republic.”

On 3 January, the Tawantinsuyuan Navy mutinied and caputred the port of Lima. Immediately, Anuhi barricaded himself in his palace with his bodyguards. By 8:00 AM, the army had seized and closed most radio and television stations in Cusco, and the air force bombed the stations that hadn’t been seized. Meanwhile, Anuhi believed that only a part of the navy and not the entire navy had mutinied. He tried contacting loyal military leaders, but nobody answered the phone. Generals and admirals loyal to Anuhi found their cars sabotaged and their phone service cut. The national police finally answered Anuhi’s call and went to the palace. When Anuhi’s defense minister emerged to ask what was going on, he was promptly arrested. Meanwhile, Anuhi was still convinced that some units remained loyal to him and that Pirama himself was still loyal. However, half an hour later, the military declared that they had seized control of all key Tawantinsuyuan cities and that Anuhi was deposed. At that point, he realized that the entire military had turned against him. Nevertheless, he refused to resign as president, despite Pirama threatening to bomb the palace. After another half hour of negotiations, Pirama broke off talks and ordered the troops sent in. It took the next five hours for the military to secure the palace, as Anuhi’s bodyguards put up large resistance. Pirama later announced that Anuhi had committed suicide by shooting himself with an AK-47. His family managed to escape to Mexico.

Bombing of the presidential palace

Two days later, Pirama’s junta dissolved the Tawantinsuyuan government and outlawed all left-wing political parties. All political activity was banned. The military took control of all media and turned them into their own propaganda machine. Although Pirama wanted to restore the Tawantinsuyuan monarchy, with himself as regent, the other generals refused to do so and instead proclaimed the Andean Republic, a right-wing military dictatorship which actively repressed thousands of suspected equalists; Pirama was still named the overall head of state and head of government. It seemed the nightmare in the Andes wouldn’t end anytime soon.

Brandt dismissed allegations that the Athanatoi had participated in the coup, insisting that everybody instead focus on the negotiations taking place in Vienna to end the Siam War. On 8 May 1972, Brandt made a major concession to Thailand by announcing that the Reich would accept a ceasefire in place as a precondition for military withdrawal. In exchange for the Thais standing down, the Reich would withdraw its forces from Siam. The concession broke a deadlock and resulted in progress in the talks over the next few months.

The first major breakthrough came on 8 October. Prior to this, Thailand had been disappointed by the results of its latest offensive, which resulted in the Reich countering with a bombing campaign that blunted the Thais’ drive to the south as well as inflicting damage in the north. Also, the Thais feared increasing isolation if Brandt’s normalization policies improved relations with China, its main backer. Thai representatives met with Kissinger, where they promised that they would let the Bangkok government remain in power. Within ten days, the two parties had finished a final draft, and Kissinger held a press conference in Constantinople, where he announced that “peace is at hand.” Pridi Panomyong likewise hailed the agreement as the “pathway to peace.”

Signing the Vienna Peace Accords

On 15 January, Brandt announced a suspension of all offensive actions against Thailand. Kissinger and his Thai counterpart met on 23 January and signed off on a treaty which called for a ceasefire in Siam and the withdrawal of Roman troops. On 27 January, the agreement was also signed by the leaders of Thailand, Siam, and the Reich in Vienna.

The Vienna Peace Accords effectively removed the Reich from the conflict in Siam. However, the agreement's provisions were routinely flouted by both the Thais and Siam, eliciting no response from the Reich (where Brandt was busy signing the Chemical Weapons Convention and establishing military and research bases in the Arctic and Antarctic), and ultimately resulting in the nationalists enlarging the area under their control by the end of 1973. The Seri Thai and Chaw Thai gradually built up their military infrastructure in the areas they controlled, preparing for one last offensive to end the war for good and reunite Thailand.

On 2 February 1973, the “1972” “Summer” Olympics began in New Xichen, Mayapan. Many countries lodged formal complaints against the IOC’s decision to host an event that was supposed to take place in the summer of 1972 in the winter of 1973 instead. Besides this controversy not much happened except for a few events. In the final of the men’s basketball, the Reich lost to the CSSR in what was called the “most controversial game in international basketball history.” In a close-fought match, the Roman team appeared to have won 50-49. But due to confusing signals from the scorer’s table, the final 3 seconds were replayed twice and the Soviet team scored two points, winning 51-50. Ultimately, the Roman team refused to accept their silver medals, which in any case remained held in a vault in Vienna. In addition, a student interrupted a marathon to join the race for the last kilometer. The crowd, thinking he was the winner after he crossed the line, began cheering him on before officials realized the hoax and removed him. Crossing the finish line, the real winner was confused to see someone ahead of him and hear the boos meant for the student.

The Soviet Commune dominated this year’s Olympics, with 50 gold and 99 total medals. The Reich came in second with 33 gold and 94 total. The DDR surprisingly beat out both India and China to come in third with 20 gold and 66 medals.

The IOC made yet another questionable decision that year when it revealed that it had awarded the next Olympics (which would probably take place in spring of 1977) to Chicago, in the Eimerican Commune. It would be the first Olympics to take place in an equalist country, which almost every capitalist country protested.

The traditionalist parties of the Reich suffered their own version of Wassertor on 20 March, when Der Spiegel revealed that a militant group associated with certain traditionalists had murdered several SPR politicians, tortured priests, and attempted to burn the mansion of CMU leader Helmut Kohl. Support for the traditionalists plummeted after the scandal broke, which was a welcome surprise for Brandt.

Final withdrawal from Lopburi

As the spring began, the Seri Thai and Chaw Thai began their final offensive against the weakened Siamese forces. While Chaw Thai forces raided other border provinces, the bulk of the conventional Seri Thai army attacked the air base at Lopburi, which fell on 1 April. The disorganized AKSM retreated to Bangkok, fortifying itself in the capital while the Chaw Thai raided the countryside as far south as the Malayan border. In one of his last public interviews before he died on 29 April, former World War II general Gustav von Anhalt (who was responsible for such things as the short-lived Venetian Offensive of 1940) remarked that while Brandt had done the right thing in getting out of Siam, he had done it too quickly.

Chiang did not bother himself with what he saw as certain victory in Thailand. Instead, he flew to Aojing, where on 3 May he officially opened the Aojing Opera House, which would be a center of culture and the arts in the Pacific.

Brandt himself tried to distance himself from Siam as best as he could, as the public’s attitude towards the war was now so toxic that any public statement remotely referring to Siam (even if it was just a single mention of “Siam” or a report of the thousands of refugees pouring across borders into Malaya and Burma and taking to the seas in barely seaworthy boats) would be met with fierce antiwar protests on hundreds of college campuses and city centers. He instead tried to focus on RANA, presiding over the launch of Himmellab, the Reich’s first space station, at the beginning of June.

(It should not say Skylab)

In October, President Park Chung-Hee gave in to protesters’ demands for elections, bringing an end to the military junta and calling for a constitutional convention. A constitution promulgated later that year established the Republic of Korea, a truly democratic republic that was technically still a satellite state of the Chinese Empire. However, Park’s call for elections and restoration of democracy only angered many generals and civilians, who variously wanted a return to the junta or a restoration of the Joseon monarchy.

(It really shouldn’t be a Chinese puppet but ignore that)

Another year passed, and the 1974 session of the Reichsrat assembled in January. As expected, the traditionalists suffered heavy losses, dropping to under 14% of seats. The equalists also lost about a quarter of their seats, most of which went to the SPR and the CMU. The liberals’ losses leveled off, and their numbers stabilized at just under 7 percent. The populists made some surprising gains, increasing to 17% of seats and becoming the third largest faction. However, they would not be able to influence policy-making in any way.

Despite Brandt’s SPR-CMU alliance controlling the Reichsrat, the Reichstag was still controlled by the KRA and FMP. As 1974 was an examination year, he hoped that he could at least ride out the year and hope that by next January the KRA’s hold on the lower house would weaken. He and the SPR began campaigning at once, expecting that it would be an easy victory .

However, an unexpected turn of events would derail all of Brandt’s plans.

Günter Guillaume (right) with Brandt

Around 1973, a year after Scheel’s resignation and with tensions still running high within the imperial government, the Athanatoi and other security organizations received information that one of Chancellor Brandt's personal assistants, Günter Guillaume, was a Stasi spy. Brandt was asked to continue work as usual, and he agreed, even taking a private vacation with Guillaume, while the Athanatoi gathered more information on him and his handlers (which wasn’t hard after they found a rather large communications device taking up half of his apartment). Guillaume was arrested on February 24, 1974.

Guillaume had indeed been a spy for East Germany, supervised by Markus Wolf, head of the Main Intelligence Administration of the East German Ministry for State Security (Stasi). According to Vasili Mitrokhin, when the KGB found out about Guillaume, they ordered Wolf to pull him out because Brandt had been a “worthy opponent” to the Soviet Commune, in Molotov’s words, and they wanted him to stay in power.

Many blamed Brandt for being so reckless as to have an equalist spy in his inner circle. Several days later Brandt was also hit with allegations of serial adultery after several women stepped forward, claiming that Brandt had affairs with them. Leading newspapers broke stories showing that he had been drinking frequently and had gone to doctors to treat depression. The oil crisis and the aftermath of Siam only placed even more stress on Brandt, who found himself under attack from all directions. As Brandt himself later said, "I was exhausted, for reasons which had nothing to do with the process going on at the time." In mid-March, the stress finally got to him, and he decided he had had enough.

On 17 March 1974, Willy Brandt officially resigned as chancellor. He would remain as chairman of the SPR until 1987.

Brandt was succeeded as Chancellor by fellow SPR leader Helmut Schmidt, who unlike Brandt belonged to the right wing (which frequently collaborated with the CMU) of the SPR. Schmidt was to serve until examinations were concluded at the end of the year.

For the rest of his life, Brandt remained suspicious that his fellow SPR member and longtime rival Herbert Wehner had schemed his downfall, but evidence for this seems scant.

Aside from internecine intrigue within the SPR, the finger of blame for Brandt's fall was also pointed at the East German leadership. Some speculated that the East German regime under Erich Honecker and the Soviet leadership under Brezhnev and Molotov had intentionally used Guillaume to engineer Brandt's downfall and humiliate the Reich. Brandt's policy of Ostpolitik had made him a hero and symbol of hope for peaceful national and family reunification in the Occupied Territories. Therefore, from Honecker's view, Brandt's popularity in East Germany represented a threat to the regime. In his memoirs, Brandt noted Honecker's denial of complicity in his downfall, adding "whatever one may think of that." However, Stasi-head Markus Wolf claimed that Brandt’s resignation had never been intended, and that the affair had been one of the biggest mistakes of the East German secret service.

Guillaume was eventually released and sent to East Germany in 1981 in exchange for Roman Athanatoi captured by the Eastern Bloc. Back in East Germany, Guillaume was celebrated as a hero, worked in the training of spies, and published his autobiography Die Aussage (The Statement) in 1982.

Like all of his predecessors, Brandt had been forced to resign before the end of his term. No chancellor had yet left office without being forced to resign. Helmut Schmidt entered the chancellery aware of this fact. He was concerned for what this held for the future of his administration...and the Ottonian system itself.

Last edited:

*乒* (not meant to be an emoticon, unlike this -->  )

)

Ouch, smallpox. Hopefully there won't be any measles outbreaks around the corner...

Ouch, smallpox. Hopefully there won't be any measles outbreaks around the corner...

Pong! Bless Dachi, a truly important landmark has been achieved.

Also, Brandt may have resigned... but he's still incredible next to his predecessor.

Also, Brandt may have resigned... but he's still incredible next to his predecessor.

Nobody in the Reich happens to be named Forrest Gump (or whatever the German version of that would be), right?A breakthrough soon followed that summer, when Chiang invited a team of Roman table tennis players to visit China and play against top Chinese players (the Romans lost).

*乓**乒* (not meant to be an emoticon, unlike this -->)

Ouch, smallpox. Hopefully there won't be any measles outbreaks around the corner...

Of course most of their customers are leftists.I think the helicopter buiseness is booming in the Andean Republic...

What predecessor? He directly took over from Ludwig Erhard. Scheel totally didn't come back to power.Pong! Bless Dachi, a truly important landmark has been achieved.

Also, Brandt may have resigned... but he's still incredible next to his predecessor.

Wald Gump might still exist, though mostly likely as a fictional character, unfortunately.Nobody in the Reich happens to be named Forrest Gump (or whatever the German version of that would be), right?

I see the ICO is up to their old shenanigans again. At least that is one thing we can rely on during these trying times.

Mein Gott, look at that Soviet Industry score! No wonder they go broke every few years, they must have no money at all ever.

There was still a Kiesinger.What predecessor? He directly took over from Ludwig Erhard. Scheel totally didn't come back to power.

Well damnThe obvious solution would be to allow the machine to be applied to non-equalists as well and then use it on the creator. If the creator isn't destroyed, the machine is unbiased enough.

The KRA is seriously pissing me off!

They clearly don't know how the Roman economy should work, and pacifism in the middle of the f***ing Cold War with the CSSR just leads to more misery.

ESPECIALLY SCHEEL

F***ING SCHEEL

ICO? Bloody olympics committee can't even get their own acronym right.I see the ICO is up to their old shenanigans again. At least that is one thing we can rely on during these trying times.

Meanwhile the Red Army just sits around doing nothing.Mein Gott, look at that Soviet Industry score! No wonder they go broke every few years, they must have no money at all ever.

We don't talk about him.There was still a Kiesinger.

Hey, at least Scheel's gone.Well damn

The KRA is seriously pissing me off!

They clearly don't know how the Roman economy should work, and pacifism in the middle of the f***ing Cold War with the CSSR just leads to more misery.

ESPECIALLY SCHEEL

F***ING SCHEEL

When they aren't invading their own puppets.Meanwhile the Red Army just sits around doing nothing.

FTFYWhen they aren't on a peacekeeping mission to nonviolently restore and maintain order in their own puppets.

No, but the KRA are still there, blocking economic reforms, and being a bunch of s***faces about interventionHey, at least Scheel's gone.

Can't support intervention if there's nothing to intervene.No, but the KRA are still there, blocking economic reforms, and being a bunch of s***faces about intervention

Can't support intervention if there's nothing to intervene.

Why fictional?*乓*

Of course most of their customers are leftists.

What predecessor? He directly took over from Ludwig Erhard. Scheel totally didn't come back to power.

Wald Gump might still exist, though mostly likely as a fictional character, unfortunately.