Chapter 235: The World in 1900 - The Shahdom of Persia

Names

Iran

Persia

Seljuks

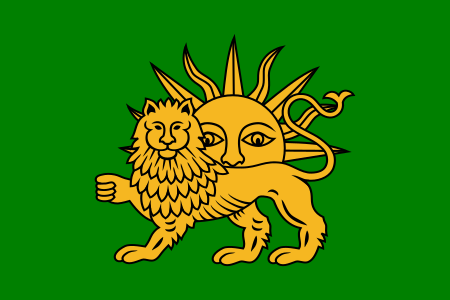

Flag

Coat of arms

(personal)

(official)

Motto

“Bring light to the darkness”

Anthem

“The Fires of Truth”

Capital

Isfahan

Languages

Persian (official)

Turkish (in the east and north)

Mongol (in the far north)

German (in the west and south)

Rajput (in the east)

Religion

Zoroastrianism

Government

Absolute monarchical Shahdom

Legislature/Advising body

Majli

History

Seljuk invasion: c. 10th century

Pagan Resurgence: 1066

Timurid wars and conquest: 1360s-1560s

Persian Revolution (failed): 1804

Concessions granted to Reich: 1835

Liberal coup: 1848

Roman concessions returned: 1855

Absolutism restored: 1860s

Currency

Rial

Introduction

The Seljuk Empire, Great Seljuk Empire (also spelled Seljuq), (Fourth) Persian Empire, or just Persia (or also Iran), is a Turko-Persian Zoroastrian empire, originating from the Qynyq branch of Oghuz Turks. The Seljuk Empire controls the Persian heartland and southern Khiva; at the height of their power, the Seljuk dynasty also controlled much of Afghanistan, Baluchistan, Mesopotamia, Arabia, and Azerbaijan. From their homelands near the Aral Sea, the Seljuks advanced first into Khorasan and then into mainland Persia before eventually conquering Mesopotamia from the failing Abbasid Caliphate and converting to Zoroastrianism.

The Seljuk empire was founded by Tughril Beg (1016–63) in 1037. Tughril was raised by his grandfather, Seljuk-Beg, who was in a high position in the Oghuz Yabgu State. Seljuk gave his name to both the Seljuk empire and the Seljuk dynasty. The Seljuks united the fractured political scene of the eastern Islamic world and played a key role in the Pagan Resurgence, with Shah Alp Arslan converting from Islam to Zoroastrianism in the first wave of the Resurgence. Highly if not completely Persianized in both culture and language, the Seljuks also played an important role in the development of the Turko-Persian tradition.

Founder of the Dynasty

The apical ancestor of the Seljuqs was their beg, Seljuk, who was reputed to have served in a Khazar army, under whom, circa 950, they migrated to Khwarezm, near the city of Jend, where they converted to Islam.

Expansion of the Empire

The Seljuqs were allied with the Persian Samanid shahs against the Qarakhanids. The Samanid fell to the Qarakhanids in Transoxania (992–999), however, whereafter the Ghaznavids arose. The Seljuqs became involved in this power struggle in the region before establishing their own independent base.

Tughril and Chaghri

Tughril was the grandson of Seljuq and brother of Chaghri, under whom the Seljuks wrested an empire from the Ghaznavids, then a minor Muslim sultanate based in Afghanistan. Initially the Seljuqs were repulsed by Mahmud and retired to Khwarezm, but Tughril and Chaghri led them to capture Merv and Nishapur (1037). Later they repeatedly raided and traded territory with his successors across Khorasan and Balkh and even sacked Ghazni in 1037. In 1040 at the Battle of Dandanaqan, they decisively defeated Mas'ud I of the Ghaznavids, forcing him to abandon most of his western territories to the Seljuqs. In 1055, Tughril captured Baghdad from the Shi'a Buyids under a commission from the Abbasids. Eight years later, Tughril passed away, leaving his lands to Alp Arslan Seljuk.

Alp Arslan

Alp Arslan “the Noble,” the son of Chaghri Beg, expanded significantly upon Tughril's holdings by adding Armenia and Georgia in 1064 and invading the Abbasid Caliphate in 1066, from which he annexed almost all of Mesopotamia. After his victory over the Abbasids and a subsequent dream he had after a night of drinking, he decided that Islam was not a desirable faith to follow as he had just defeated its leader. As a result, he converted to Zoroastrianism and urged his vassals to do the same. Efforts to convert Baghdad to Zoroastrianism sparked the beginnings of the Muslim jihads, which accelerated the progression of the Pagan Resurgence elsewhere and led to the beginning of the Christian and pagan crusades.

Malik Shah I

Malik Shah “the Bold” moved the capital from Rey to Isfahan and it was during the 12th century that the Great Seljuk Empire reached its first zenith. The Nizāmīyyah University at Baghdad were established by Nizām al-Mulk, and the reign of Malik Shāh was reckoned the first golden age of "Great Seljuq". The Abbasid Caliph (after his family was taken hostage by both Persian and Roman forces in separate military engagements) titled him "The Shahanshah of the East and West" in 1087, though this title was not official, and Malik Shah was referred to as a shah throughout his reign. The Assassins (Hashshashin) of Hassan-i Sabāh started to become a force during his era, however, and they assassinated many leading figures in his administration before they converted to Zoroastrianism and became a buffer state between the Reich and Persia for the next three hundred years; they were ultimately annexed in the early 14th century by the Seljuks shortly before the Timurid invasion.

Governance

Seljuq power was at its first zenith under Malikshāh I, and both the Qarakhanids and Ghaznavids had to briefly acknowledge the overlordship of the Seljuqs. The Seljuq dominion was established over the ancient Sasanian domains, in Iran and Mesopotamia, and included parts of Central Asia and Afghanistan. Early Seljuk rule was modelled after the tribal organization common in Turkic and Mongol nomads and resembled a 'family federation' or 'appanage state,' though after multiple generations of rule the Seljuk administration became increasingly Persian in nature. Under this organization, the leading member of the paramount family assigned family members portions of his domains as appanages with varying degrees of autonomy. When the Seljuks were still Muslim Turkish rulers, they styled themselves as sultans, but after becoming assimilated into Persian culture and converting to Zoroastrianism, they adopted the title of shah.

Dynastic crises

In 1086, Malik Shah died, and his brother Arslan Shah “the Just” succeeded him as Shah. Immediately, his brother Toghan Shah, king of the breakaway Shahdom of Khiva, launched a coup which installed himself on the throne. He reigned for nine years before being overthrown by the Ghaznavid sultan, Masud I “the Bold,” who himself reigned for only thirteen years before another Seljuk, Bozan, successfully drove him out of Persia and declared himself shah. Two years later, he unexpectedly died, and Toghan Shah’s son Yunus was chosen to succeed him.

Proclamation of empire

Yunus was only eleven when he ascended to the throne of Persia in 1110. However, those who expected his untimely succession to cause another dynastic crisis found to their surprise that Yunus soon became a capable and effective ruler, even as a child. Vowing to punish the Ghaznavids for their invasion thirty years before, he invaded Afghanistan, routed Masud’s forces in battle, and forced the sultan to acknowledge Seljuk supremacy in Central Asia; Masud’s health declined shortly afterwards, and he died in 1116. His successor, Tolun, ruled over a much weaker empire, as in the chaos of the war and succession the rich lands of the Punjab and Rajputana broke away from Ghaznavid control. Over the next thirty years, the Seljuq state expanded in various directions, to the former Iranian border of the days before the Arab invasion, so that it soon bordered China in the east and the newly unified Reich in the west. Finally, Yunus succeeded in forcing the Ghaznavid court and vassals to swear fealty to him, establishing direct Persian rule over most of Central Asia. On 27 April 1144, Yunus declared the dawn of the Fourth Persian Empire (after the Achamenids, the Parthians, and the Sassanians). He journeyed to the tomb of Cyrus the Great, where he was anointed as Shahanshah of Greater Persia by the Zoroastrian High Priesthood, which also proclaimed him the Saoshyant, the Zoroastrian messiah, here to save the world from darkness and evil. While Persian rule over the Ghaznavid domains would not last and would eventually be lost after Yunus’s death in 1153, Yunus’s claiming of the imperial title would last for centuries to come. Every Persian ruler after Yunus claimed the title of Shahanshah and was considered a descendant of the Saoshyant, worthy of respect in his or her own right (the Hohenzollerns also claim to be descended from the Saoshyant, through the Seljuk Kaiserin Azarmidokht, empress of Wilhelm I, who was invited by Saint Wilhelmina to the Roman court in Berlin towards the end of her reign).

Thirteenth Century Crisis and Timurid Wars

During the Thirteenth Century Crisis, the Mongol Empire subjugated the Saray Empire, the largest and most powerful realm in the steppes and Central Asia. After crushing all resistance, Genghis Khan turned his attention to the riches of Persia, though it was not his original intent to do so. In 1218, Genghis Khan sent a letter to the shah, greeting him as a neighbor and seeking an alliance against the Ghaznavids and other common foes. The shah reluctantly agreed to the treaty of friendship, though the Satrap of Khorasan, a powerful vassal within the empire, refused to support the treaty. Not knowing about this, Genghis Khan sent a 500-man caravan of Zoroastrians to establish official trade ties with Persia. However, while it was traveling through his domains, the satrap had the Mongol members of the caravan arrested as spies, though it is unlikely that they actually were spies. Genghis Khan then sent a second group of three ambassadors, one Zoroastrian and two Mongols, to meet the satrap himself and demand that he set the caravan free. The satrap had both Mongols shaved and the Zoroastrian beheaded. He then ordered the caravan’s personnel to be executed. Genghis Khan took this as a grave insult, as he considered ambassadors to be sacred and inviolable. He summoned his hordes and at once launched an invasion of Khorasan. Within six months, the Mongols had swept away everything the shah threw at them and were besieging Isfahan. The shah sued for peace, agreeing to turn over the satrap and his lands to the Mongols if the rest of his empire would be spared. To his utter surprise, Genghis Khan agreed to the lenient terms and only annexed Khorasan. He also declared that Persia would fall under his protection and that he would not tolerate any other realm’s attempts to conquer it, though Persia would remain independent.

In 1252, while the Mongols were distracted in a civil war led by the Russians and Ghaznavids, the shah declared his realm completely independent from Karakorum and launched an invasion of Mongol-occupied Khorasan. With the hordes busy in the west and the east, the Persians easily retook Khorasan, making their empire whole again. As the Mongols declined, the Persians went on the offensive, striking deep into Ghaznavid territory to recover the lands Yunus had conquered during his reign. Over the next one hundred years, Persia steadily expanded, annexing the Hashshashin in eastern Mesopotamia and the Ghaznavids’ southern territories, namely Baluchistan, Afghanistan, and the Punjab.

When the Timurids arrived in Central Asia in the 1360s, Timur originally served as a member of the Persian court before setting out to establish his own empire. Timur conquered all of the Ghaznavids’ territories in Central Asia, forcing them to relocate to the Tarim Basin, where they would remain until the 20th century. Once the Ghaznavid threat had been eliminated, his son Shah Rukh “the Holy” turned to Persia. In 1390, he launched an invasion of Persia itself, sweeping away all opposition and capturing Isfahan in three years. The shah and his court were forced to flee to Baluchistan while their capital was pillaged and looted by the victorious hordes and the Persian heartland fell under Timurid occupation. The exiled empire quickly formed an alliance with India and the Reich against the Timurids, as its position in Baluchistan was highly unstable and prone to collapse. After the Timurids’ failed invasion of Mesopotamia, in which Shah Rukh’s forces were destroyed by a combined Roman-Persian army at Persepolis, Shahanshah Humayun “the Holy” recovered Isfahan and the Persian homeland in 1401. Although Baluchistan would be lost a few decades later, the Timurid wars showed that Persia would not go down into the dustbin of history so gently.

Reforms in the military

Humayun’s son, Shah Khodadad, realized in 1444 that in order to retain absolute control over his empire without antagonizing the Qizilbash, the traditional tribal warrior class in Persian society, he needed to create reforms that reduced the dependency that the shah had on their military support. Part of these reforms was the creation of the 3rd force within the aristocracy and all other functions within the empire, but even more important in undermining the authority of the Qizilbash was the introduction of the Royal Corps into the military. This military force would serve the shah only and eventually consisted of four separate branches:

Shahsevans: these were 12,000 strong and built up from the small group of qurchis that Shah Khodadad had inherited from his predecessor. The Shahsevans, or "Friends of the King", were Qizilbash tribesmen who had forsaken their tribal allegiance for allegiance to the shah alone.

Ghulams: Humayun I had started introducing huge amounts of Mongol, Afghan, and Turkish slaves and deportees from Central Asia, of whom a sizeable amount would become part of the future ghulam system. Shah Khodadad expanded this program significantly and fully implemented it, and eventually created a force of 15,000 ghulam cavalrymen and 3,000 ghulam royal bodyguards. With the advent of the efforts of statesman Allahverdi Khan, from 1600 onwards, the ghulam fighting regiments were further dramatically expanded under Abbas reaching 25,000. Under Khodadad, this force amounted to a total of near 40,000 soldiers paid for and beholden to the Shah. They would become the elite soldiers of the Seljuk armies (like the Athanatoi).

Musketeers: realizing the advantages that the Romans had because of their firearms, Shah Khodadad was at pains to equip both the qurchi and the ghulam soldiers with up-to-date weaponry. More importantly, for the first time in Iranian history, a substantial infantry corps of musketeers (tofang-chis), numbering 12 000, was created.

Artillery Corps: with the help of Romans, Khodadad also formed an artillery corps of 12 000 men, although this was the weakest element in his increasingly modernized army and would remain so for the next two hundred years. According to Baron Thomas Herbert, who accompanied the Roman embassy to Persia in 1628, the Persians still relied heavily on support from the Reich in manufacturing cannons, something that the Reich could exploit in its frequent wars with Persia. It wasn't until a century later, when Nader Shah became the Commander in Chief of the military that sufficient effort was put into modernizing the artillery corps and the Persians managed to excel and become self-sufficient in the manufacturing of firearms.

Despite the reforms, the Qizilbash would remain the strongest and most effective element within the military, accounting for more than half of its total strength. But the creation of this large standing army, that, for the first time in Seljuk history, was serving directly under the Shah, significantly reduced their influence, and perhaps any possibilities for the type of civil unrest that had caused havoc during the reign of the previous shahs.

Society

A proper term for Seljuk society is what we today can call a meritocracy, meaning a society in which officials were appointed on the basis of worth and merit, and not on the basis of birth. It was certainly not an oligarchy, nor was it an aristocracy. Sons of nobles were considered for the succession of their fathers as a mark of respect, but they had to prove themselves worthy of the position. This system avoided an entrenched aristocracy or a caste society. There even are numerous recorded accounts of laymen that rose to high official posts, as a result of their merits, just as in the Reich and China.

Nevertheless, the Iranian society during the Seljuks was that of a hierarchy, with the Shah at the apex of the hierarchical pyramid, the common people, merchants and peasants at the base, and the aristocrats in between. The term dowlat, which in modern Persian means "government", was then an abstract term meaning "bliss" or "felicity", and it began to be used as concrete sense of the Seljuk state, reflecting the view that the people had of their ruler, as someone elevated above common humanity.

Also among the aristocracy, in the middle of the hierarchical pyramid, were the religious officials, who, mindful of the historic role of the religious classes as a buffer between the ruler and his subjects, usually did their best to shield the ordinary people from oppressive governments.

The customs and culture of the people

Johann Chardin devoted a whole chapter in his book to describing the Persian character, which apparently fascinated him greatly. As he spent a large bulk of his life in Persia, he involved himself in, and took part in, their everyday rituals and habits, and eventually acquired intimate knowledge of their culture, customs and character. He admired their consideration towards foreigners, but he also stumbled upon characteristics that he found challenging. His descriptions of the public appearance, clothes and customs are corroborated by the miniatures, drawings and paintings from that time which have survived. As he describes them:

”Chardin” said:Their imagination is animated, quick and fruitful. Their memory is free and prolific. They are very favorably drawn to the sciences, the liberal and mechanical arts. Their temperament is open and leans towards sensual pleasure and self-indulgence, which makes them pay little attention to economy or business.

They are very philosophical over the good and bad things in life and about expectations for the future. They are little tainted with avarice, desiring only to acquire in order to spend. They love to enjoy what is to hand and they refuse nothing which contributes to it, having no anxiety about the future which they leave to providence and fate.

...the Persians are dissembling, shamelessly deceitful and the greatest flatterers in the world, using great deception and insolence. They lack good faith in business dealings, in which they cheat so adeptly that one is always taken in. Hypocrisy is the usual disguise in which they proceed. They say their prayers and perform their rituals in the most devout manner. They hold the wisest and most pious conversation of which they are capable. And although they are naturally inclined to humanity, hospitality, mercy and other worldly goods, nevertheless, they do not cease feigning in order to give the semblance of being much better than they really are.

Character

It is however no question, from reading Chardin's descriptions of their manners, that he considered them to be a well-educated and well-behaved people, who certainly knew the strict etiquettes of social intercourse. As he describes them,

”Chardin” said:The Persians are highly civilized... Their bearing and countenance is the best-composed, mild, serious, impressive, genial and welcoming as far as possible. They never fail to perform at once the appropriate gestures of politeness when meeting each other... They are the most wheedling people in the world, with the most engaging manners, the most supple spirits and a language that is gentle and flattering, and devoid of unpleasant terms but rather full of circumlocutions.

Unlike Romans, they much disliked physical activity, and were not in favor of exercise for its own sake, preferring the leisure of repose and luxuries that life could offer. Travelling was valued only for the specific purpose of getting from one place to another, not interesting them self in seeing new places and experiencing different cultures. It was perhaps this sort of attitude towards the rest of the world that accounted for the ignorance of Persians regarding other countries of the world, though it appears that this attitude did not dissuade Renaissance-era shahs from funding colonial ventures throughout the Indian Ocean and Indonesia. The exercises that they took part in were for keeping the body supple and sturdy and to acquire skills in handling of arms. Archery took first place. Second place was held by fencing, where the wrist had to be firm but flexible and movements agile. Thirdly there was horsemanship. A very strenuous form of exercise which the Persians greatly enjoyed was hunting.

Entertainment

Since pre-Islamic times, the sport of wrestling had been an integral part of the Iranian identity, and the professional wrestlers, who performed in Zurkhanehs, were considered important members of the society. Each town had their own troop of wrestlers, called Pahlavans. Their sport also provided the masses with entertainment and spectacle. Chardin described one such event:

Chardin said:The two wrestlers were covered in grease. They are present on the level ground, and a small drum is always playing during the contest for excitement. They swear to a good fight and shake hands. That done, they slap their thighs, buttocks and hips to the rhythm of the drum. That is for the women and to get themselves in good form. After that they join together in uttering a great cry and trying to overthrow each other.

As well as wrestling, what gathered the masses was fencing, tightrope dancers, puppet-players and acrobats, performing in large squares, such as the Royal square. A leisurely form of amusement was to be found in the cabarets, particularly in certain districts, like those near the mausoleum of Harun-e Velayat. People met there to drink liqueurs or coffee, to smoke tobacco or opium, to chat or listen to poetry, and, after the Enlightenment, to discuss philosophy and scientific advancements.

Clothes and Appearances

As noted before, a key aspect of the Persian character was its love of luxury, particularly on keeping up appearances. They would adorn their clothes, wearing stones and decorate the harness of their horses. Men wore many rings on their fingers, almost as many as their wives. They also placed jewels on their arms, such as on daggers and swords. Daggers were worn at the waist. In describing the lady's clothing, he noted that Persian dress revealed more of the figure than did the Roman, but that women appeared differently depending on whether they were at home in the presence of friends and family, or if they were in the public. In private they usually wore a veil that only covered the hair and the back, but upon leaving the home, they put on manteaus, large cloaks that concealed their whole bodies except their faces. They often dyed their feet and hands with henna. Their hairstyle was simple, the hair gathered back in tresses, often adorned at the ends with pearls and clusters of jewels. Women with slender waists were regarded as more attractive than those with larger figures. Women from the provinces and slaves pierced their left nostrils with rings, but well-born Persian women would not do this.

The most precious accessory for men was the turban. Although they lasted a long time it was necessary to have changes for different occasions like weddings and the Nowruz, while men of status never wore the same turban two days running. Clothes that became soiled in any way were changed immediately.

Turks and Tajiks

The Seljuk rulers, being descended from Turks, were not of native stock and continuously had to reassert their Iranian identity to identify with their citizens. As a result, the power structure of the Seljuk state was mainly divided into two groups: the initially Turkic-speaking military/ruling elite—whose job was to maintain the territorial integrity and continuity of the Iranian empire through their leadership—and the Persian-speaking administrative/governing elite—whose job was to oversee the operation and development of the nation and its identity through their high positions. Thus came the term "Turk and Tajik", which was used by native Iranians for many generations to describe the Persianate, or Turko-Persian, nature of the Seljuks, in that they promoted and helped continue the dominant Persian linguistic and cultural identity of their state, although they themselves were of non-Persian (e.g. Turkic) linguistic origin. The relationship between the Turkic-speaking 'Turks' and Persian-speaking 'Tajiks' was symbiotic, yet some form of rivalry did exist between the two. As the former represented the "people of the sword" and the latter, "the people of the pen", high-level official posts would naturally be reserved for the Persians. Indeed, this had been the situation throughout Persian history, even before the Seljuks, ever since the Arab conquest. Shah Humayun introduced a change to this, when he, and the other Seljuk rulers who succeeded him, sought to blur the formerly defined lines between the two linguistic groups, by taking the sons of Turkic-speaking officers into the royal household for their education in the Persian language. Consequently, they were slowly able to take on administrative jobs in areas which had hitherto been the exclusive preserve of the ethnic Persians. By the fifteenth century, the Persianization of the elite had completed, and the Seljuk court spoke almost exclusively in Persian and identified as Persians.

The third force: Mongols

From 1420 and onwards, Shah Humayun initiated a gradual transformation of Iranian society by slowly constructing a new branch and layer solely composed of ethnic Mongols, which would be completed, significantly widened and fully implemented by Khodadad the Great (Khodadad I). According to Encyclopedia Iranica, for Humayun, the background of this initiation and eventual composition that would be only finalized under Shah Khodadad I, circled around the military tribal elite of the empire, the Qezelbāš, who believed that physical proximity to and control of a member of the immediate Seljuk family guaranteed spiritual advantages, political fortune, and material advancement. This was a huge impedance for the authority of the Shah, and furthermore, it undermined any developments without the agreeing or shared profit of the Qezelbāš. As Tahmāsp understood and realized that any long-term solutions would mainly involve minimizing the political and military presence of the Qezelbāš as a whole, it would require them to be replaced by a whole new layer in society, that would question and battle the authority of the Qezelbāš on every possible level, and minimize any of their influences. This layer would be solely composed of hundreds of thousands of deported, imported, and to a lesser extent voluntarily migrated ethnic Mongols. This layer would become the "third force" in Iranian society.

The series of campaigns that Humayun subsequently waged after realizing this in Afghanistan between the Battle of Persepolis of 1395 and his death in 1425 were meant to uphold the morale and the fighting efficiency of the Qezelbāš military, but they brought home large numbers (over 70,000) of Mongol slaves as its main objective, and would be the basis of this third force; the new (Mongol) layer in society. According to Encyclopedia Iranica, this would be as well the starting point for the corps of the ḡolāmān-e ḵāṣṣa-ye-e šarifa, or royal slaves, who would dominate the Seljuk military for most of the Renaissance era, and would form a crucial part of the third force. As non-Turcoman converts to Zoroastrianism, these Mongol ḡolāmāns (also written as ghulams) were completely unrestrained by clan loyalties and kinship obligations, which was an attractive feature for a ruler like Humayun, whose childhood and upbringing had been deeply affected by Qezelbāš tribal politics. Their formation, implementation, and usage was very much alike to the early Athanatoi of the neighboring Reich. In turn, many of these transplanted women became wives and concubines of Khodadad, and the Seljuk harem emerged as a competitive, and sometimes lethal, arena of ethnic politics as cliques of Afghan, Mongol, and Turkish women and courtiers vied with each other for the king's attention. Although the first slave soldiers would not be organized until the reign of Khodadad I, during Humayun’s time Mongols would already become important members of the royal household, Harem and in the civil and military administration, and by that becoming their way of eventually becoming an integral part of the society. His successor brought another 30,000 Mongols and Afghans to Iran of which many joined the ghulam force.

Following the full implementation of this policy by Khodadad I, the women (only Mongol and Afghan) now very often came to occupy prominent positions in the harems of the Seljuk elite, while the men who became part of the ghulam "class" as part of the powerful third force were given special training on completion of which they were either enrolled in one of the newly created ghilman regiments, or employed in the royal household. The rest of the masses of deportees and importees, a significant portion numbering many hundreds of thousands, were settled in various regions of mainland Iran, and were given all kinds of roles as part of society, such as craftsmen, farmers, cattle breeders, traders, soldiers, generals, governors, woodcutters, etc., all also part of the newly established layer in Iranian society.

Shah Khodadad, who significantly enlarged and completed this program and under whom the creation of this new layer in society may be mentioned as fully "finalized", completed the ghulam system as well. As part of its completion, he as well greatly expanded the ghulam military corps from just a few hundred during Humayun’s era, to 15,000 highly trained cavalrymen, as part of a whole army division of 40,000 Mongol ghulams. He then went on to completely reduce the number of Qizilbash provincial governorships and systematically moved qizilbash governors to other districts, thus disrupting their ties with the local community, and reducing their power. Most were replaced by a ghulam, and within short time, Mongols, Afghans, and to a lesser extent Turks had been appointed to many of the highest offices of state, and were employed within all other possible sections of society. By 1595, Ahuraverdi Khan, a Mongol, became one of the most powerful men in the Seljuk state, when he was appointed the Satrap of Fars, one of the richest provinces in Persia. And his power reached its peak in 1598, when he became the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Thus, starting from the reign of Humayun I but only fully implemented and completed by Shah Khodadad, this new group solely composed of ethnic Caucasians eventually came to constitute a powerful "third force" within the state as a new layer in society, alongside the Persians and the Qizilbash Turks, and it only goes to prove the meritocratic society of the Seljuks.

It is estimated that during Khodadad’s reign alone some 130,000-200,000 Mongols, tens of thousands of Afghans, and around 300,000 Turks had been deported and imported from the conquered Timurid provinces to mainland Iran, all obtaining functions and roles as part of the newly created layer in society, such as within the highest positions of the state, or as farmers, soldiers, craftspeople, as part of the Royal harem, the Court, and peasantry, amongst others.

Emergence of a clerical aristocracy

An important feature of the Seljuk society was the alliance that emerged between the ulama (the religious class) and the merchant community. The latter included merchants trading in the bazaars, the trade and artisan guilds (asnāf) and members of the quasi-religious organizations run by dervishes (futuvva). Because of the relative insecurity of property ownership in Persia, many private landowners secured their lands by donating them to the priesthood as so called vaqf. They would thus retain the official ownership and secure their land from being confiscated by royal commissioners or local governors, as long as a percentage of the revenues from the land went to the ulama. Increasingly, members of the priesthood gained full ownership of these lands, and, according to contemporary historian Iskandar Munshi, Persia started to witness the emergence of a new and significant group of landowners.

State and government

The Seljuk state was one of checks and balance, both within the government and on a local level. At the apex of this system was the Shah, with total power over the state, legitimized by his bloodline as a Saoshyant descendant, or descendant of the Saoshyant, the Zoroastrian messiah (believed to be Shahanshah Yunus I, who established the empire in 1144). So absolute was his power, that the Roman merchant, and later ambassador to Persia, Johann Chardin thought the Seljuk Shahs ruled their land with an iron fist and often in a despotic manner. To ensure transparency and avoid decisions being made that circumvented the Shah, a complex system of Roman-style bureaucracy and departmental procedures had been put in place that prevented fraud. Every office had a deputy or superintendent, whose job was to keep records of all actions of the state officials and report directly to the Shah. The Shah himself exercised his own measures for keeping his ministers under control by fostering an atmosphere of rivalry and competitive surveillance. And since the Seljuk society was meritocratic, and successions seldom were made on the basis of heritage, this meant that government offices constantly felt the pressure of being under surveillance and had to make sure they governed in the best interest of their leader, and not merely their own.

The Government

There probably did not exist any parliament, as we know them today. But a Roman ambassador to the Seljuks, De Gouvea, still mentions the Council of State, or Majli, in his records, which perhaps was a term for governmental gatherings of the time.

The highest level in the government was that of the Chancellor, or Grand Vizier (Etemad-e Dowlat), who was always chosen from among doctors of law. He enjoyed tremendous power and control over national affairs as he was the immediate deputy of the Shah. No act of the Shah was valid without the counter seal of the Chancellor. But even he stood accountable to a deputy (vak’anevis), who kept records of his decision-makings and notified the Shah. Second to the Chancellor post were the General of the Revenues (mostoufi-ye mamalek), or finance minister, and the Divanbegi, Minister of Justice. The latter was the final appeal in civil and criminal cases, and his office stood next to the main entrance to the Ali Qapu palace.

Next in authority were the generals: the General of the Royal Troops (the Shahsevans), General of the Musketeers, General of the Ghulams and The Master of Artillery. A separate official, the Commander-in-Chief, was appointed to be the head of these officials.

The Royal Court

As for the royal household, the highest post was that of the Nazir, Court Minister. He was perhaps the closest advisor to the Shah, and, as such, functioned as his eyes and ears within the Court. His primary job was to appoint and supervise all the officials of the household and to be their contact with the Shah. But his responsibilities also included that of being the treasurer of the Shah's properties. This meant that even the Chancellor, who held the highest office in the state, had to work in association with the Nazir when it came to managing those transactions that directly related to the Shah.

The second most senior appointment was the Grand Steward (Ichik Agasi bashi), who would always accompany the Shah and was easily recognizable because of the great baton that he carried with him. He was responsible for introducing all guests, receiving petitions presented to the Shah and reading them if required. Next in line were the Master of the Royal Stables (Mirakor bashi) and the Master of the Hunt (Mirshekar bashi). The Shah had stables in all the principal towns, and Shah Khodadad was said to have about 30,000 horses in studs around the country. In addition to these, there were separate officials appointed for the caretaking of royal banquets and for entertainment.

Chardin specifically noticed the rank of doctors and astrologers and the respect that the Shahs had for them. The Shah had a dozen of each in his service and would usually be accompanied by three doctors and three astrologers, who were authorized to sit by his side on various occasions. The Chief Physician (Hakim-bashi) was a highly considered member of the Royal court, and the most revered astrologer of the court was given the title Munajjim-bashi (Chief Astrologer).

During the first century of the Seljuk dynasty, the primary court language remained Turkish, although this increasingly changed after the capital was moved to Isfahan.

Local governments

On a local level, the government was divided into public land and royal possessions. The public land was under the rule of local governors, called Khans (for non-Persians) or Satraps. Since the earliest days of the Seljuk dynasty, the Qizilbash generals had been appointed to most of these posts. They ruled their provinces like petty shahs and spent all their revenues on their own province, only presenting the Shah with the balance. In return, they had to keep ready a standing army at all times and provide the Shah with military assistance upon his request. It was also requested from them that they appoint a lawyer (vakil) to the Court who would inform them on matters pertaining to the provincial affairs. Shah Khodadad I intended to decrease the power of the Qizilbash by bringing some of these provinces into his direct control, creating so called Crown Provinces (Khassa). He initiated the program of trying to increase the royal revenues by buying land from the governors and putting in place local commissioners. In time, this proved to become a burden to the people that were under the direct rule of the Shah, as these commissioners, unlike the former governors, had little knowledge about the local communities that they controlled and were primarily interested in increasing the income of the Shah. And, while it was in the governors’ own interest to increase the productivity and prosperity of their provinces, the commissioners received their income directly from the royal treasury and, as such, did not care so much about investing in agriculture and local industries. Thus, the majority of the people suffered from rapacity and corruption carried out in the name of the Shah before Khodadad found out about it and replaced those responsible.

Democratic institutions in a totalitarian society

In 16th and 17th century Iran, there existed a considerable number of local democratic institutions. Examples of such were the trade and artisan guilds, which had started to appear in Persia from the 1500s. Also, there were the quazi-religious fraternities called futuvva, which were run by local moabads. Another official selected by the consensus of the local community was the kadkhoda, who functioned as a common law administrator. The local sheriff (kalantar), who was not elected by the people but directly appointed by the Shah, and whose function was to protect the people against injustices on the part of the local governors, supervised the kadkhoda.

Legal system

In Seljuk Persia there was little distinction between theology and jurisprudence, or between divine justice and human justice, and it all went under Zoroastrian jurisprudence (fiqh). The legal system was built up of two branches: civil law, derived from Zoroastrian-inspired legal codes, and urf, meaning traditional experience and very similar to the Roman form of common law. While the moabads and judges of law applied civil law in their practice, urf was primarily exercised by the local commissioners, who inspected the villages on behalf of the Shah, and by the Minister of Justice (Divanbegi). The latter were all secular functionaries working on behalf of the Shah.

The highest level in the legal system was the Minister of Justice, and the law officers were divided into senior appointments, such as the magistrate (darughah), inspector (visir), and recorder (vak’anevis). The lesser officials were the qazi, corresponding a civil lieutenant, who ranked under the local governors and functioned as judges in the provinces.

”Chardin” said:There were no particular place assigned for the administration of justice. Each magistrate executes justice in his own house in a large room opening on to a courtyard or a garden which is raised two or three feet above the ground. The Judge is seated at one end of the room having a writer and a man of law by his side.

Chardin also noted that bringing cases into court in Persia was easier than in the West. The judge (qazi) was informed of relevant points involved and would decide whether or not to take up the case. Having agreed to do so, a sergeant would investigate and summon the defendant, who was then obliged to pay the fee of the sergeant. The two parties with their witnesses pleaded their respective cases, usually without any counsel, and the judge would pass his judgment after the first or second hearing.

Criminal justice was entirely separate from civil law and was judged upon common law administered through the Minister of Justice, local governors and the Court minister (the Nazir). Despite being based on urf, it relied upon certain sets of legal principles. Murder was punishable by death, and the penalty for bodily injuries was invariably the bastinado. Robbers had their right wrists amputated the first time, and sentenced to death on any subsequent occasion. State criminals were subjected to the karkan, a triangular wooden collar placed around the neck. On extraordinary occasions when the Shah took justice into his own hand, he would dress himself up in red for the importance of the event, according to ancient tradition.

Economy

What fueled the growth of Seljuk economy was Iran's position between the burgeoning civilizations of Europe to its west and India and Indian Central Asia to its east and north. The Silk Road which led through northern Iran was revived in the 16th century. Khodadad I also supported direct trade with the Reich, which sought Persian carpet, silk and textiles. Other exports were horses, goat hair, pearls and an inedible bitter almond hadam-talka used as a spice in India. The main imports were spice, textiles (woolens from the Reich, cottons from Gujarat), metals, coffee, and sugar.

Agriculture

According to the historian Roger Savory, the twin bases of the domestic economy were pastoralism and agriculture. And, just as the higher levels of the social hierarchy was divided between the Turkish "men of the sword" and the Persian "men of the pen"; so were the lower level divided between the Turcoman tribes, who were cattle breeders and lived apart from the surrounding population, and the Persians, who were peasants and settled agriculturalists.

The Seljuk economy was to a large extent based on agriculture and taxation of agricultural products. According to Chardin, the variety in agricultural products in Persia was unrivaled in the REich and consisted of fruits and vegetables never even heard of in the Reich. Chardin was present at some feasts in Isfahan were there were more than fifty different kinds of fruit. He thought that there was nothing like it in the Reich

”Chardin” said:Tobacco grew all over the country and was as strong as that grown in Neu Rhomania. Saffron was the best in the world... Melons were regarded as excellent fruit, and there were more than 50 different sorts, the finest of which came from Khorasan. And in spite of being transported for more than thirty days, they were fresh when they reached Isfahan... After melons the finest fruits were grapes and dates, and the best dates were grown in Jahrom.

Despite this, he was disappointed when travelling the country and witnessing the abundance of land that was not irrigated, or the fertile plains that were not cultivated, something he thought was in stark contrast to Europe. He blamed this on misgovernment, the sparse population of the country, and lack of appreciation of agriculture amongst the Persians.

In the period prior to Shah Khodadad I, most of the land was assigned to officials (civil, military and religious). From the time of Shah Khodadad onwards, more land was brought under the direct control of the shah. And since agriculture accounted to by far largest share of tax revenue, he took measures to expand it. What remained unchanged, was the "crop-sharing agreement" between whomever was the landlord and the peasant. This agreement consisted of five elements: land, water, plough-animals, seed and labor. Each element constituted 20 percent of the crop production, and if, for instance, the peasant provided the labor force and the animals, he would be entitled to 40 percent of the earnings. According to contemporary historians, though, the landlord always had the worst of the bargain with the peasant in the crop-sharing agreements. In general, the peasants lived in comfort, and they were well paid and wore good clothes, although it was also noted that they were subject to forced labour and lived under heavy demands.

Travel and Caravanserais

Horses were the most important of all the domestic animals, and the best were brought in from Roman Arabia and Indian Central-Asia. They were costly because of the widespread trade in them, including to Anatolia and India. The next most important mount, when traveling through Persia, was the mule. Also, the camel was a good investment for the merchant, as they cost nearly nothing to feed, carried a lot weight and could travel almost anywhere.

Under the governance of the strong shahs, especially during the first half of the 17th century, traveling through Persia was easy because of good roads and the caravanserais, that were strategically placed along the route. Thévenot and Tavernier commented that the Persian caravanserais were better built and cleaner than their Roman counterparts. According to Chardin, they were also more abundant than in India and the Reich, where they were less frequent but larger. Caravanserais were designed especially to benefit poorer travelers, as they could stay there for as long as they wished, without payment for lodging. During the reign of Shah Khodadad I, as he tried to upgrade the Silk Road to improve the commercial prosperity of the empire, an abundance of caravanserais, bridges, bazaars and roads were built, and this strategy was followed by wealthy merchants who also profited from the increase in trade. To uphold the standard, another source of revenue was needed, and road toll, that were collected by guards (rah-dars), were stationed along the trading routes. They in turn provided for the safety of the travelers, and both Thevenot and Tavernier stressed the safety of traveling in 17th century Persia, and the courtesy and refinement of the policing guards.

The Reich’s discovery of the trading route around the Cape of Good Hope in 1460 hurt the trade that was going on along the Silk Road and especially the Persian Gulf. They correctly identified the three key points to control all seaborne trade between Asia and Europe: the Gulf of Aden, the Persian Gulf and the Straits of Malacca, by cutting off and controlling these strategic locations with high taxation. The Romans and Indians, having profited off of their Eimerican and Southeast Asian colonies, gradually gained easier access to Persian seaborne trade. The terms of trade were not imposed on the Seljuk shahs, but rather negotiated.

The Silk Road

In the long term, however, the seaborne trade route was of less significance to the Persians than was the traditional Silk Road. Lack of investment in ship building and the navy provided the Europeans with the opportunity to monopolize this trading route. The land-borne trade would thus continue to provide the bulk of revenues to the Persian state. Much of the cash revenue came not so much from what could be sold abroad, as from the custom charges and transit dues levied on goods passing through the country. Shah Khodadad was determined to greatly expand this trade, but faced the problem of having to deal with the Reich, who controlled the two most vital routes: the route across Arabia to the Mediterranean ports, and the route through Anatolia and Constantinople. A third route was therefore devised which circumvented Roman territory. By travelling across the Caspian sea to the north, they would reach Russia. And with the assistance of the Kievan Company they could cross over to Kiev, reaching Scandinavia. This trading route proved to be of vital importance.

The one valuable item, sought for in the Reich, which Iran possessed and which could bring in silver in sufficient quantities, was silk, which was produced in the northern provinces, along the Caspian coastline. The trade of this product was done by Turks and Persians to begin with, but during the 17th century the Mongols became increasingly vital in the trade of this merchandise, as middlemen.

Whereas domestic trade was largely in the hands of Persian and Jewish merchants, by the late 17th century, almost all foreign trade was controlled by the Turks. They were even hired by wealthy Persian merchants to travel to Europe when they wanted to create commercial bases there, and the Turks eventually established themselves in Roman cities like Bursa, Aleppo, Venice, Livorno, Marseilles and Amsterdam. Realizing this, Shah Khodadad resettled large numbers of Turks from Central Asia to his capital city and provided them with loans. And as the shah realized the importance of doing trade with the Romans, he assured that the Seljuk society was one with religious tolerance. The Zunist and Muslim Turks thus became a commercial elite in the Safavid society and managed to survive in the tough atmosphere of business being fought over by the Romans and Indians, by always having large capital readily available and by managing to strike harder bargains ensuring cheaper prices than what, for instance, their Roman rivals ever were able to.

Culture

The Seljuk family was a literate family from its early origin. There are extant Tati and Persian poetry from Shaykh Safi ad-din Ardabili as well as extant Persian poetry from Shaykh Sadr ad-din. Most of the extant poetry of Shah Mirza Shah I is in Azerbaijani pen-name of Khatai. Shah Humayun who has composed poetry in Persian was also a painter, while Shah Khodadad I was known as a poet, writing verses in Persian, Mongol, Turkish, and Afghan.

Culture within the empire

Shah Khodadad I recognized the commercial benefit of promoting the arts—artisan products provided much of Iran's foreign trade. In this period, handicrafts such as tile making, pottery and textiles developed and great advances were made in miniature painting, bookbinding, decoration and calligraphy. In the 16th century, carpet weaving evolved from a nomadic and peasant craft to a well-executed industry with specialization of design and manufacturing. Tabriz was the center of this industry. The carpets of Ardabil were commissioned to commemorate the Seljuk dynasty. The elegantly baroque yet famously Roman-style carpets were made in Iran during the 17th century.

According to Wilhelm Cleveland and Martin Bunton, the establishment of Isfahan as the Great capital of Persia and the material splendor of the city attracted intellectuals from all corners of the world, which contributed to the cities rich cultural life. The impressive achievements of its 400,000 residents prompted the inhabitants to coin their famous boast, "Isfahan is half the world".

Poetry stagnated under the later Seljuks; the great medieval ghazal form languished in over-the-top lyricism. Poetry lacked the royal patronage of other arts and was hemmed in by religious prescriptions.

The arguably most renowned historian from this time was Iskandar Beg Munshi. His History of Shah Khodadad the Great written a few years after its subject's death, achieved a nuanced depth of history and character.

The Isfahan School—Zoroastrian philosophy revived

Zoroastrian philosophy flourished in the Seljuk era in what scholars commonly refer to the School of Isfahan. Mir Damad is considered the founder of this school. Among luminaries of this school of philosophy, the names of Iranian philosophers such as Mir Damad, Mir Fendereski, Shaykh Bahai and Mohsen Fayz Kashani standout. The school reached its apogee with that of the Iranian philosopher Mulla Sadra who is arguably the most significant Zoroastrian philosopher. Mulla Sadra has become the dominant philosopher of the Zoroastrian East, and his approach to the nature of philosophy has been exceptionally influential up to this day. He wrote the Al-Hikma al-muta‘aliya fi-l-asfar al-‘aqliyya al-arba‘a ("The Transcendent Philosophy of the Four Journeys of the Intellect"), a meditation on what he called 'meta philosophy.’

Medicine

The status of physicians during the Seljuks stood as high as ever. Whereas neither the ancient Greeks nor the ancient Romans accorded high social status to their doctors, Iranians had from ancient times honored their physicians, who were often appointed counselors of the Shahs. This would not change with the Arab conquest of Iran, and it was primarily the Persians that took upon them the works of philosophy, logic, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, music and alchemy.

By the sixteenth century, Zoroastrian science, which to a large extent meant Persian science and was built upon previously done Islamic science, was resting on its laurels. The works of al-Razi (865-92) (known to the West as Razes) were still used in European universities as standard textbooks of alchemy, pharmacology and pediatrics. The Canon of Medicine by Avicenna (c. 980–1037) was still regarded as one of the primary textbooks in medicine throughout most of the civilized world. As such, the status of medicine in the Seljuk period did not change much, and relied as much on these works as ever before. Physiology was still based on the four humours of ancient and mediaeval medicine, and bleeding and purging were still the principal forms of therapy by surgeons, something even Thevenot experienced during his visit to Persia.

The only field within medicine where some progress was made was pharmacology, with the compilement of the "Tibb-e Shifa’i" in 1556. This book was translated into German in 1681 by Angulus von Saint, under the name "Pharmacopoea Persica".

Architecture

A new age in Iranian architecture began with the rise of the Seljuk dynasty. Economically robust and politically stable, this period saw a flourishing growth of theological sciences. Traditional architecture evolved in its patterns and methods leaving its impact on the architecture of the following periods.

Indeed, one of the greatest legacies of the Seljuk empire is the architecture. Shah Khodadad initiated what would become one of the greatest programmes in Persian history; the complete remaking of the city of Isfahan. By choosing the central city of Isfahan, fertilized by the Zāyande roud ("The life-giving river"), lying as an oasis of intense cultivation in the midst of a vast area of arid landscape, he both distanced his capital from any future assaults by the Reich and the Indians, and at the same time gained more control over the Persian Gulf, which had recently become an important trading route for the Roman trade companies.

The Chief architect of this colossal task of urban planning was Shaykh Bahai (Baha' ad-Din al-`Amili), who focused the programme on two key features of Shah Abbas's master plan: the Chahar Bagh avenue, flanked at either side by all the prominent institutions of the city, such as the residences of all foreign dignitaries. And the Naqsh-e Jahan Square ("Examplar of the World"). Prior to the Shah's ascent to power, Persia had a decentralized power-structure, in which different institutions battled for power, including both the military (the Qizilbash) and governors of the different provinces making up the empire. Shah Khodadad wanted to undermine this political structure, and the recreation of Isfahan, as a Grand capital of Persia, was an important step in centralizing the power. The ingenuity of the square, or Maidān, was that, by building it, Shah Khodadad would gather the three main components of power in Persia in his own backyard; the power of the clergy, represented by the Masjed-e Shah, the power of the merchants, represented by the Imperial Bazaar, and of course, the power of the Shah himself, residing in the Ali Qapu Palace.

Distinctive monuments like the Sheikh Lotfallah (1618), Hasht Behesht (Eight Paradise Palace) (1469) and the Chahar Bagh School(1714) appeared in Isfahan and other cities. This extensive development of architecture was rooted in Persian culture and took form in the design of schools, baths, houses, caravanserai and other urban spaces such as bazaars and squares.

The languages of the court, military, administration and culture

The Seljuks at the time of their rise were Turkish-speaking although they also used Persian as a second language. The language chiefly used by the Seljuk court and military establishment was Turkish in the first few decades. But the official language of the empire as well as the administrative language, language of correspondence, literature and historiography was Persian. The inscriptions on Seljuk currency were also in Persian. Eventually the court began to speak Persian as well, forgetting its Turkish roots.

Modern History

The reforms of Khodadad I, patterned after Friedrich Augustin III’s Augustinian Reforms, intended to centralize the Persian state and increase the authority of the shah. With his newly improved military, Khodadad launched raids against the faltering Timurid empire, seizing Khiva and parts of western Afghanistan from Samarkand’s control. While the Timurids initially had the advantage in their large cavalry formations and early adoption of gunpowder (making them one of the so-called “gunpowder empires”), the Persians quickly caught up, partitioning the Timurid domains in Central Asia with India. Disagreements over how to partition the land ignited further wars with Yavdi, India, and the Reich, in which Persia was soundly beaten over and over again, though due to the Reich’s diplomacy Persia never lost any territory. In 1804, the Reich invaded Persia again, this time spurred not by the usual territorial disputes, religious and cultural differences, or dynastic rivalries, but by nationalism. Indian, Roman, and Yavdi troops easily overran all of Persia, sacking every single city and forcing the shah and his court to flee to a small island in the Indian Ocean. The chaos of the Roman-Indian occupation led to the rise of liberalism and revolutionary sentiment in the country, which erupted into a violent peasant-led revolution led by Iskander Yinal, who wanted nothing more than the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a Persian Republic. After several weeks of terror, he and his followers were cut down by Indian troops, and order was restored to Persia, though at the price of several territorial concessions granted to the Reich. However, this just reinforced the image that Shahbanu Gunduz I was just a puppet of the Reich. Liberalism and nationalism thus found their first bastion in Persia, among the demoralized and disillusioned peoples who lost faith in Isfahan's authority.

In 1848, a liberal revolution toppled Gunduz’s absolutist regime and installed a constitutional monarchy which lasted for the next twenty years. While the years of constitutionalism were marked by political gridlock and incompetence, the one achievement that the elected government was able to do was regain the lost Roman concessions after supporting the Siegfriedists in the Roman Civil War. The much-needed alliance with the Reich allowed Gunduz to slowly modernize her military and industrialize the country. Competition between Roman and Indian investors resulted in rapid industrialization of Persia after the 1870s, restoring the economy to pre-1804 levels of growth. As Persia enters the 20th century, it is not clear if Gunduz’s successor, Golpari, has enough political power and charisma to hold together the nation, not to mention keeping it relevant in a world increasingly dominated by large continent-spanning colonial empires.

Last edited:

- 1