The Gaitskell Years: A New Look at New Britain [NWO2]

- Thread starter DensleyBlair

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

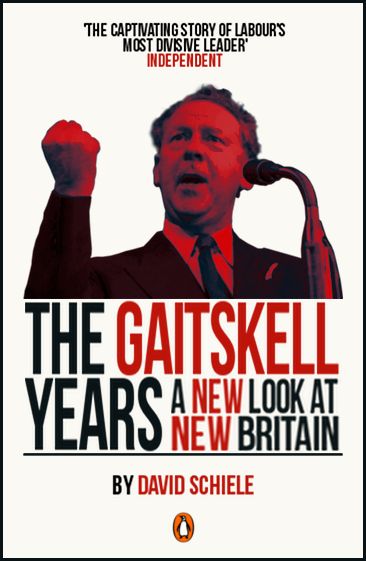

Hello everyone, and welcome to my latest project: The Gaitskell Years. Inspired largely by a recent urge to write about a more modern Britain than that which I've previously covered, this will be somewhat different to my other works (if, indeed, one can describe them so generously) in that its focus will be on a very specific (and brief) time in British history. This is as much for my own benefit and sanity as because I've been toying with the idea for a while of charting the fortunes of a single person in British history - in this case, that man is Hugh Gaitskell.

Why Hugh Gaitskell? Well, that aspect of inspiration came after reading the Francis Beckett-edited The Prime Ministers Who Never Were, which got me thinking about how I might feasibly recreate some of the situations speculated upon in my own games and writing. Of all of the people included, Gaitskell jumped out the strongest. In our timeline, he died before ever becoming PM – yet his differences with his successor, Harold Wilson, and the general fun to be had with the sixties setting, provide some really fascinating what-ifs. (For people like me, anyway. )

)

The other main difference of this AAR to my other projects, as the eagle-eyed will have noticed, is that I have adopted a definite writer persona. Whilst I have never explicitly written as DensleyBlair, neither have I ever played with the idea of an author having a certain voice or concrete way of viewing things. With the relative proximity of the subject matter of what follows, I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to try that sort of thing out. (It also gives me an excuse to design Penguin covers, so a boon all-round really.)

Of course, there are many people without whom this project likely would never have come to anything. Of those on these forums, I must thank Tanzhang for his indispensable counsel over the last few weeks, both political and aesthetic; Tommy4Ever, for giving me the idea of using the New World Order mod in his excellent The Westminster System; and, of course, Bizon and the rest of the New World Order team. There are many other worthies out there, I'm sure, and so I must apologise if anyone feels I've missed anyone.

I hope you all enjoy what follows. I'm optimistic that I might actually finish this one – though I appreciate that people may be somewhat sceptical of that particular phrase. At this point, I should probably mention that this does not mean that A Biography is in any way dead; if you're a reader (and, if so, what excellent taste you have!) please do not worry.

With that, I give you my many thanks, and I hope to see you all for the ride,

Why Hugh Gaitskell? Well, that aspect of inspiration came after reading the Francis Beckett-edited The Prime Ministers Who Never Were, which got me thinking about how I might feasibly recreate some of the situations speculated upon in my own games and writing. Of all of the people included, Gaitskell jumped out the strongest. In our timeline, he died before ever becoming PM – yet his differences with his successor, Harold Wilson, and the general fun to be had with the sixties setting, provide some really fascinating what-ifs. (For people like me, anyway.

The other main difference of this AAR to my other projects, as the eagle-eyed will have noticed, is that I have adopted a definite writer persona. Whilst I have never explicitly written as DensleyBlair, neither have I ever played with the idea of an author having a certain voice or concrete way of viewing things. With the relative proximity of the subject matter of what follows, I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to try that sort of thing out. (It also gives me an excuse to design Penguin covers, so a boon all-round really.)

Of course, there are many people without whom this project likely would never have come to anything. Of those on these forums, I must thank Tanzhang for his indispensable counsel over the last few weeks, both political and aesthetic; Tommy4Ever, for giving me the idea of using the New World Order mod in his excellent The Westminster System; and, of course, Bizon and the rest of the New World Order team. There are many other worthies out there, I'm sure, and so I must apologise if anyone feels I've missed anyone.

I hope you all enjoy what follows. I'm optimistic that I might actually finish this one – though I appreciate that people may be somewhat sceptical of that particular phrase. At this point, I should probably mention that this does not mean that A Biography is in any way dead; if you're a reader (and, if so, what excellent taste you have!) please do not worry.

With that, I give you my many thanks, and I hope to see you all for the ride,

Densley

Last edited:

My relationship with Hugh Gaitskell was perhaps never truly representative of the majority of contemporary members of the Labour Party, especially the parliamentary party. Without slipping too far into autobiography (after all, this isn't a book about me; there are enough of those already, and I'm responsible for most of them!) I entered Parliament in 1952, at a time when the Gaitskellites were beginning to consolidate their dominance over the rival supporters of Nye Bevan. This being the way of things, coupled with my own personal tendency to inhabit a position within the moderate wing of the party, I naturally drifted towards Gaitskell's group of acolytes and eventually became a committed ally, and later still a good friend, of the man himself.

It is therefore quite likely thanks to Hugh Gaitskell's leadership of the party that my political career panned out as it did. As his own mentor Hugh Dalton had before him, Gaitskell's predisposition was for promoting a loyal clique with him – first within the party hierarchy, and then of course within government. I was afforded such opportunities, joining the shadow cabinet after the election of 1959 and then later occupying a seat on the front bench when we ultimately acceded to government. By the reckoning of a great many, this level of involvement with the dominant forces in the party during the Gaitskell era would make me a Gaitskellite. My own views on the subject are not so clear cut.

I tend to consider that any period of overt factionalism within the Labour Party is dangerous in that it produces not only divisiveness, but a climate in which it is all too easy to pin people's masts to passing zeitgeists. Gaitskell's leadership is something of an oddity in this regard as, whereas he did not come from the extreme fringes of the party to lead – far from it – he led in a time where differences between groups were so pronounced that the threshold for what was perceived as radicalism was infinitely reduced. Therefore, a figure whose brand of socialism was not in any way opposed to what the Labour Party should embody became a standout figure, to whom countless future party figures with ideas of modernisation would run the risk of comparison – myself included at times.

Nevertheless, to rein in this lengthy digression and return to my original question, I do not consider myself to have remained a Gaitskellite for my entire career. This is largely due to the fact that I am sceptical of seeking to carve out arbitrary dividing lines within the party, but primarily because I also believe that Hugh Gaitskell's socialist beliefs are not as extraordinary as has been hinted previously. He was a moderniser who helped to bring the party away from the pursuit of the more utopian socialism of Attlee's New Jerusalem and towards a modern and dynamic New Britain. His vision was idealistic, but also pragmatic; egalitarian but technocratic, symbolised as much by Gaitskell's own firm belief in Keynesianism as by the social liberalism of another acolyte, Roy Jenkins. These are traits I believe should be found in any good leader of the Labour Party, hence my reluctance to ascribe them specifically to one man. I was brought into the upper echelons of the Labour movement by Hugh Gaitskell, but I did not remain in his shadow. Or so I like to think.

Gaitskell's time in office was undoubtedly tumultuous and divisive, and there is no denying that he was responsible for many actions and decisions that still divide the opinion not just of the Labour Party, but of the entire country. If one looks past the controversy, however, what one finds as a result of his leadership is, ultimately, the creation of a better, fairer and more equal Britain. I therefore very much welcome this new retelling of Gaitskell's time in office and hope that it may inspire a wider, fresh re-examination of one of the most compelling episodes of this country's recent political history.

Denis Healey,

September 2015

September 2015

Last edited:

This view, whilst arguably valid, fails in many ways to represent the entire story. Hugh Gaitskell was a complicated figure, and his time in Downing Street was even more so. Both during his brief four-year tenure at the top of Disraeli's 'greasy pole' and in the surrounding years, Britain struggled, often fiercely, with competing notions of what it meant to be a world power. It was a complex time, after all: one of immense contradictions and troubles as the country tried to define its place in the post-war world during the height of the Cold War. Yet it was also a time of great positive change as Gaitskell's 'New Britain' came to represent a more equal and humane society, marked by social reform and technological advancement.

When I was first approached to write this book two years ago, I was therefore apprehensive. Being an academic only in the sense that I have a degree, I had doubts as to whether I would be truly able to convey the nuances and subtleties of what it meant to be a citizen of New Britain. In many ways, writing this book was a surreal experience as I came to really understand the world into which I was born for the first time. Researching this book meant researching the Britain of my youth, which was a revelatory experience to say the least. (As a ten-year-old, I was always more engaged with the worlds of Brian Clough and David Bowie than with that of Harold Wilson and Ted Heath.) Nevertheless, I feel that I have done the period justice.

This could have been a gruelling and mammoth task. It was, in relative terms – though in a highly masochistic way it was always enjoyable. The writing of a book is, after all, a large commitment for many – not just the author. I have endeavoured, however, to keep things succinct. Hugh Gaitskell's unique position within the canon of both Labour's history and wider British history means that there has been no dearth of analysis of his government and its legacy over the years. Dr Brian Brivati's seminal Hugh Gaitskell of course remains the most comprehensive portrait of the period, as well as being a far superior example of a political biography than anything I could ever create. I have no pretensions that this book is in any way as exhaustive, or indeed as good, as previous works. Neither do I wish to give the impression that this is a political biography, though any study of a head of government will naturally veer into biography at times. Rather, I intend for this to serve as a means of popularising the history of a period that remains deeply controversial in the hope of not only increasing awareness of one of twentieth century Britain's most divisive figures, but also of perhaps inspiring fresh enquiry into his legacy – a legacy that, whether we like it or not, is still felt today.

David Schiele,

September 2015

September 2015

Beautiful work Densley and it is grand to see you again after The Westminster System!

Ye Libdem Yellow $*%(#$

Ye Libdem Yellow $*%(#$

Oh, you know I'm subbing.

BTW, I liked how Healey's foreword was longer than four brief sentences.

BTW, I liked how Healey's foreword was longer than four brief sentences.

While I was hoping for an update in the Other Place, this looks fascinating, nice graphics and interesting model for the AAR.

I had vague plans for a post-war Britain AAR myself, though beyond some notes and graphics nothing came of it. However DB I did collect a decent treasure trove of online sources for the period dealing with decolonisation, immigration, Britain's nuclear arsenal, Butskellism etc. I'd be happy to send you all the links if it would be of any use to you.

I had vague plans for a post-war Britain AAR myself, though beyond some notes and graphics nothing came of it. However DB I did collect a decent treasure trove of online sources for the period dealing with decolonisation, immigration, Britain's nuclear arsenal, Butskellism etc. I'd be happy to send you all the links if it would be of any use to you.

Count me subbed

I know nothing of the Labour or British politics at the time though so I hope I won't be lost

I know nothing of the Labour or British politics at the time though so I hope I won't be lost

Count me subbed

I know nothing of the Labour or British politics at the time though so I hope I won't be lost

This is pretty much the story of Tony Blair before Tony Blair emerged, if I read the hints correctly. Count me in btw.

- 1

Beautiful work Densley and it is grand to see you again after The Westminster System!

Thanks Doctor Stein! Good to see you again, too – especially following along.

Ye Libdem Yellow $*%(#$

Lib Dem? Moi?!

Oh, you know I'm subbing.

Wonderful to see you so promptly.

BTW, I liked how Healey's foreword was longer than four brief sentences.

Be fair to the man: I'm fairly certain it was five brief sentences.

Yuck, Labour.

It's excellent to see you, all the same.

While I was hoping for an update in the Other Place, this looks fascinating, nice graphics and interesting model for the AAR.

Thanks Jape! Good to see you, as ever. An update in the Other Place is still on the cards, but I felt I needed to take a more definite break from it more than anything. Recharge the batteries sort of thing.

I had vague plans for a post-war Britain AAR myself, though beyond some notes and graphics nothing came of it. However DB I did collect a decent treasure trove of online sources for the period dealing with decolonisation, immigration, Britain's nuclear arsenal, Butskellism etc. I'd be happy to send you all the links if it would be of any use to you.

Well, great minds and all that… If you would send them my way, that would be really appreciated. Thanks for offering.

Count me subbed

I know nothing of the Labour or British politics at the time though so I hope I won't be lost

Excellent to see you, Attalus! I trust I'll be able to go some way to helping you understand things. Not that it's in any way requisite for following along, of course.

This is pretty much the story of Tony Blair before Tony Blair emerged, if I read the hints correctly. Count me in btw.

Gaitskell and Blair were both revisionists to a degree, that's for sure. Whether Tony Blair will be as relevant in this world is of course an entirely different matter…

Great to see you here, by the way.

Coincidence for me to have learned a little bit about Gaitskell in my History class, only to find an AAR surrounding him.

Good luck. I shall be keeping track.

Good luck. I shall be keeping track.

Very well written, no less than what we can expect from you

Also, I positively adore the Penguin cover art - good job on that as well.

Also, I positively adore the Penguin cover art - good job on that as well.

Coincidence for me to have learned a little bit about Gaitskell in my History class, only to find an AAR surrounding him.

Coincidence indeed! Hopefully this will be a nice little complement to what you learn in your history class.

Good luck. I shall be keeping track.

Thank you very much! It'll be good to have you on board.

Very well written, no less than what we can expect from you

Also, I positively adore the Penguin cover art - good job on that as well.

Well that's all very kind of you to say. Thank you for checking this out, and I hope you'll think just as highly of what follows.

Sounds interesting, subscribed.

Thanks loup! Good to see you here.

_____________________________

I'm hopeful of having the first 'chapter' up at some point over the weekend – likely either Friday evening or Saturday afternoon. It'll just be an overview of how Gaitskell came to join the Labour Party in preparation for the main event, if you will – so nothing that one could strictly define as an AAR yet, I'm afraid

Still, everything has to start somewhere.

Until then.

Coincidence indeed! Hopefully this will be a nice little complement to what you learn in your history class.

I'm sure it will.

Hugh Gaitskell was not born into the Labour movement. Eventually, the seeds of social justice would take root in the young man and inspire a devotion to the Labour Party deeper than that expressed by many with more conventionally 'Labour' upbringings, but the world of nationalisation and planned economies was far removed from that in which Gaitskell grew up.

He was born in 1906, the youngest child of Arthur 'Tiger' Gaitskell and Addie Mary Jamieson. Both his father and his godfather, after whom he was named, held posts in the Indian civil service, though the Gaitskell family came originally from Cumberland and had roots in military service that dated back to at least the Napoleonic era. On his mother's side, Hugh was descended from Scottish farmers via a consul-general of Shanghai. As Brivati says, 'his world was defined by the British Empire. By the time Sam [as the young boy was known] entered this world it was already characterised by a lightly fading privilege and a dusty gentility'.

Not that his family were without a radical streak of their own. His father Arthur made the seismic decision to drop out of Oxford and take a civil service job in Burma at the age of only nineteen. Later, Arthur would pursue his future wife, Gaitskell's mother Addie, all the way to Scotland having fallen in love with her on a boat journey back from Burma. This readiness to deviate from the path apparently laid out for his at birth (public school, Oxbridge, respectable career) perhaps goes some way to explaining the alacrity with which Hugh would later go on to adopt the values of the Labour movement. Gaitskell's father was, as far is reliably ascertainable, no bourgeois radical or class traitor, but neither was he an entirely stereotypical product of his high Victorian imperial middle class origins.

This high Victorian imperialism would ultimately survive Victoria herself and last into the first years of Sam's childhood. Gaitskell spent his first summer in Burma, as well as an entire year when he was five, and his experiences of the Empire at its peak would go on to influence his thinking for the rest of his life. A bright and precocious boy, his was a Kiplingesque early childhood that saw as its central axis British Values and the British Empire. This upbringing would later manifest itself within Gaitskell's personality as a struggle between the conflicting demands of emotion and convention, characterised most tellingly by a habit of blushing when speaking that Sam maintained well into the 1920s.

At the age of six, having returned from Burma to live mostly permanently in Oxford, where he stayed with a cousin of his father's, Sam entered the prestigious Dragon School. The Dragon was founded originally as a preparatory school for the sons of Oxford dons after liberalising university reforms in the 1870s allowed dons to marry, and was dominated by ideas of Gladstonian liberalism even into the twentieth century. By contrast with Oxford's other prep school, Summerfields – notably attended by Harold Macmillan until the year of Gaitskell's birth – the Dragon was by far the more dynamic institution in the area. It's headmaster 'Skipper' Lynam was an 'ardent radical', relatively tolerant for the time (beatings were infrequent by contemporary standards) and enjoyed the twin passions of boating and dressing in a loud and extravagant manner. (Gaitskell later led a trend for what Bertie Wooster might describe as 'fruity' neckties amongst his fellow Draconians, including a young John Betjeman, after the Skipper's lead.) Nevertheless, the school maintained demanding standards, by which Hugh – a slow starter – was good, if not outstanding. Academically, he finished fifth out of 200, winning prizes for bathing and divinity along the way.

'Skipper' Lynam, the dominant force at the Dragon during the young Gaitskell's time.

The young Gaitskell also took to the Dragon's keen sporting tradition with enthusiasm, learning to box and play rugby – though his prime loves were tennis and golf, the latter a passion which stayed with him for life. The highlight of his sporting career may well have been captaining the second cricket eleven, though Gaitskell himself was sceptical of his cricketing talents and opined in his diary many years later that his captaincy was more likely 'because of vague qualities of leadership rather than any ability to hit the ball'. Even if he was personally uncertain about it, this would mark the first of many leadership positions occupied by Gaitskell during his life.

Gaitskell's time at the Dragon was clouded somewhat in 1915 when his father Arthur died of a tropical disease, aged only forty-five. In his place, Gaitskell came to idolise his brother – also Arthur – who had also been closer to the young Sam. Hugh followed his older brother first to the Dragon and then on to Winchester and New College, Oxford. As a consequence, the younger boy was always in the shadow of the elder, though relations between them were very loving – even after Hugh rebelled against Arthur's own lack of rebellion in later years. Arthur always remained more definitely within 'his own class' than his younger brother.

In 1919, the year Hugh moved from the Dragon to the even more feted Winchester School, the Gaitskell children acquired a step-father in the form of Gilbert Wodehouse, a cousin of P. G., who promptly moved with Addie back to India. This was a watershed period for Hugh, who was first properly introduced to the idea of social justice after a meeting with the father of a school friend around the same time. Hugh told him he was off to Winchester, to which the father replied: 'You don't know how lucky you are – only one boy in ten thousand has the chance of an education like that'. Hugh claimed later that this was his 'first awareness of a social problem'.

Winchester was a more fitting background than might first be supposed against which this nascent 'socialism' (if it could yet be called such) could flourish. Founded in 1382 by William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester, three years after Wykeham had founded New College at Oxford, the school was instituted as a place where 'poor and indigent scholars' might be transformed into 'men of great learning, fruitful to the church … King and realm'. The school had itself greatly transformed in the intervening 537 years between its inception and the arrival of Hugh Gaitskell and, whilst it was by no means as aristocratic as other famous public schools, it was renowned for what Dick Crossman – very much the star of Winchester when Hugh first went up – described later as a 'blend of intellectual arrogance and conventional good manners'. Brivati suggests that this 'captures something of Gaitskell in his later life'.

A depiction of Winchester College, whose architecture would go on to inform New College, Oxford, amongst other institutions.

Gaitskell's own time at Winchester was far from stellar. Indeed, it failed even to really live up to the modest heights of his time as a Draconian, beginning inauspiciously with the failure to obtain a scholarship and generally continuing in the same vein in spite of Gaitskell's own hard work ethic. In the opinion of Crossman's biographer Tam Dalyell, this supreme unremarkableness even had ramifications during Gaitskell's time at the top of the Labour Party, with Crossman apparently never regarding him as much other than the 'amiable and ineffective schoolboy'. Roy Jenkins concurs in his own biography of Gaitskell, writing that: 'He was a much less successful Wykehamist than either of his Labour Party contemporaries, Richard Crossman or Douglas Jay'. Jay's own first impression of Gaitskell was formed in the aftermath of the latter having failed in a cross-country race that he was tipped to win – though it is perhaps worth noting here that Jay would go on to be described as 'the first Gaitskellite'.

Eventually, Gaitskell was able to make something of his Winchester days – even if he never really held the place in as high regard as the other institutions of his childhood. His hard work meant that he caught up with Crossman just below the sixth form, sitting in second place behind him (and ahead of two future wardens of Oxford colleges, amongst others). He also managed to cultivate an interest in foreign affairs whilst at the school, and his crowning moment as a Wykehamist was indubitably winning a prize for an essay he had written on international arbitration. The prize was sponsored by the then-lawyer and later chancellor Stafford Cripps, whom Gaitskell met as a result of his triumph. He not overly impressed meeting his hero for the first time, who spoke to him during a hurried discussion in a taxi necessitated by Cripps' hectic schedule about a need for the unification of the Christian churches of the world in order to bring about world peace.

Gaitskell left Winchester for Oxford in 1924, and his time at his second school could not be called a great success in any aspect. Academically, he made up for a general mediocrity with hard work, and even his sporting pursuits had suffered from the sense of apathy that pervaded much of Sam's activity at the school. Emotionally too Gaitskell had yet to really find his feet, and entered Oxford a typical product of his time and his upbringing: privately charismatic and loving, though publicly reserved and measured – altogether about as sure of himself in this area of life as any other adolescent boy fresh out of five years boarding at a public school. He therefore entered New College with little ambition other than to win a golfing blue. Ultimately, however, Gaitskell's time at Oxford would provide him with both a solid foundation on which to base his adult life, and with many important and lasting friends who together shaped Gaitskell's life perhaps more than any group of people had before. It was at Oxford that Gaitskell first met Evan Durbin, his socialist mentor and later closest ideological ally.

Throughout out his Oxford career, Gaitskell moved predominantly between two circles: one, the set of largely homosexual aesthetes headed by figures such as Maurice Bowra, John Betjeman and W. H. Auden; the other, a more serious group of leading Oxonian socialists dominated by the Coles, G. D. H. and Margaret, and Evan Durbin. He balanced both well, often using one as an antidote to the other, though cannot be said to have fully committed to either. A legend that Gaitskell once consented to John Betjeman touching his bottom ('Oh well, if you must', Gaitskell supposedly replied) is as close as one can get to any hints that he ever experimented sexually. His conversion to socialism, meanwhile, was not immediately forthcoming. Gaitskell socialising as he did can be seen as a direct reaction to the repressed instincts of his earlier upbringing, and that the culmination of this reaction came in the form of his eventual socialist Damascene moment and not in the form of open homosexuality is perhaps telling of where his true intent lay.

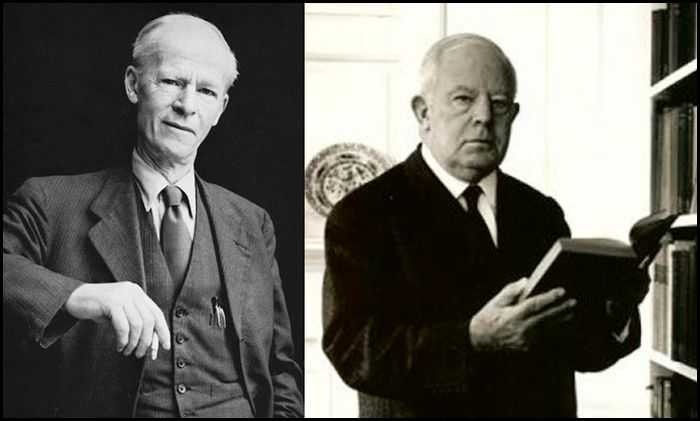

G. D. H. Cole (left) and Maurice Bowra, whose competing salons Gaitskell frequented at Oxford.

He would have to wait until 1926 for his conversion, however – specifically, the general strike attempted by the trade unions between the 3rd and the 12th of May. Gaitskell had been reading Marx, the Webbs and Hugh Dalton as part of his studies of politics, philosophy and economics – then a very adventurous mix of subjects, today of course almost cliché amongst politicians – and this, combined with a general support for the underdog in all situations, pushed him firmly onto the side of the striking workers. Gaitskell remained a democratic socialist for the rest of his life.

Gaitskell's support for the miners drove him, in this case quite literally, to the Coles' residence, where he arrived one day in May 1926 to offer his help in their work aiding the strike effort. This work involved borrowing a friend's car and driving his patrons from Oxford to London in order that they could transport messages and text for strike papers. This was when Gaitskell first was given a union card. Whilst the exact date is unclear, it appears that he joined the Labour Party at the same time. These driving trips – always done at some speed so as to allow the undergraduate Gaitskell to return in time to get back to New College before it was gated up for the night – can be placed as one of the major milestones in the introduction of Gaitskell to the socialist movement. During a few frenetic days in London, he was introduced to editors of the newspapers of the labour movement, bigwigs from the General Workers' Union and even taken to the House of Commons.

Following the strike, Gaitskell chose G. D. H. Cole's specialist subject of the labour movement for his extended essay, which was published by the Workers' Educational Association some years later. The essay is a document of the history and evolution of the labour movement from radical beginnings in the 1780s to the Chartists of the early Victorian period. It marks the start of a more radical period for Gaitskell, which was hardened in the following years after the Wall Street Crash and the rise of political extremism. Although never truly comfortable with the doctrine, in the late 1920s Gaitskell did advocate the class struggle and even defended the Soviet Union to Evan Durbin. He never lost his sense of the importance of the individual, however, which made his flirtations with Marxism quite idiosyncratic, and by the 1930s Keynesianism had given him the framework he needed to form an economic philosophy that included both state action and individual freedom.

Scenes from Crewe during the General Strike, which embedded in Gaitskell a commitment to the working classes.

He left Oxford with a first in PPE in 1927 and was offered two jobs: one, to write a history of the Chartist leader Feargus O'Connor; the other to join the Workers' Education Association as an extramural lecturer in Nottingham. Gaitskell had previously to his mother that he would seek a job with the WEA if his interest in politics continued and so it was not hard for him to resist her insistences to go into the Indian civil service and take the Nottingham job. The strikes of the previous year had marked the start of Gaitskell's maturation, both personally and politically ("I doubt if I will ever play golf again", Frank Longford remembers him saying) and his time in Nottingham only helped this process along. In Nottingham, which Gaitskell rather oddly began to see as a place of great freedom and real politics – likely as he had never truly lived independently prior to his time there – Gaitskell first came into prolonged contact with the working class, whom he found 'the nicest sort of people'. Writing to his brother, he lauded the miners he taught as 'more honest and natural than the Middle Class who are always trying to be something they aren't'. Gaitskell, very much from the 'Top Drawer' of the common classes, never tried to ape or patronise the miners, which consequently earned him their great respect. (He would later have a similar advantage in South Leeds.) His first tentative steps as a lecturer were hardly those of a firebrand leftist, however, and some of his first talks on morality and religion were decried as conservative 'irreligious nonsense'.

Embracing the freedom of Nottingham, Gaitskell even managed to prove himself wrong to a point by continuing his sporting endeavours – though golf was replaced by tennis. Ballroom dancing, another great passion picked up at Oxford that would last his entire life (Barbara Castle once described Gaitskell as 'a very good dancer'[1]) became important as a means of meeting women. He had some serious encounters with local women, though none survived his move to London the next year. Indeed, it is hard to escape from the idea that Gaitskell's time in the East Midlands was ultimately more important politically, renewing his commitment to the working class, to whom Gaitskell had pledged his future in 1926. Brivati suggests that Gaitskell thought of Nottingham as almost a year of 'national service in socialism' until the end of his life. His time there certainly always stayed with him as a happy one, and he was reluctant to leave for University College, London in 1928, when he was offered the post of assistant lecturer in the economics department by Noel Hall. His reluctance was overcome after some prodding by old tutors H. A. L. Fisher, then still the dominant liberal historian of his day, and G. D. H. Cole. London would prove even more important than Nottingham in his socialist maturation, not only by offering Gaitskell the 'vitality' he desired so that he may do something for the labour movement, but also by allowing him regular contact with Hugh Dalton.

The relationship between Dalton and Gaitskell would prove one of the most important, if not the most important, in Gaitskell's political life. Dalton was by the 1930s already a prominent figure in the Labour Party, and would eventually serve as Attlee's chancellor. Dalton moved in a world of left-wing intellectuals centred around Bloomsbury focussed on providing means for the redistribution of wealth in society, therefore something of a commanding figure generally in the Labour movement's intelligentsia. Writing in 1956, Gaitskell credited Dalton with impressing upon him the importance of differences in wealth rather than factors of production, helping perhaps to moderate the young man at a time when he was going through one of his more radical phases.

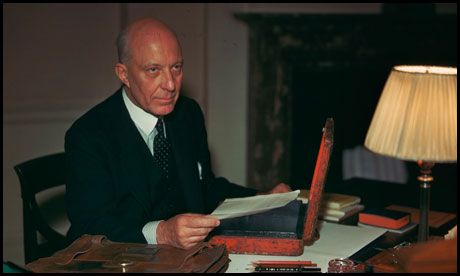

Dalton as chancellor. During the 1930s, he was the biggest influence on Gaitskell's career.

Also important was Dalton's ability to introduce Gaitskell to sets of like-minded young socialists, specifically those centred around Bloomsbury. Most notable was the XYZ Club, sometimes known as the City Group, founded in 1932. Along with Evan Durbin, Dalton introduced Gaitskell to the Club, whose aim was to foster stronger links and a closer understanding between the labour movement and the financiers of the City of London. The group was at the vanguard of what has variously been termed, perhaps unfairly, as 'Low Bloomsbury', in contrast to the Edwardian 'High Bloomsbury' of Virginia Woolf and company. Whilst still undoubtably urbane and fun, this new set of movers and shakers in Bloomsbury were dedicated to altogether more serious causes than their aesthetically-inclined forebears. Economics, specifically the then-radical new theories of John Maynard Keynes, were their prime focus, and together they did a great deal to further the acceptance of Keynesian theory. Indeed, Gaitskell is often credited with popularising Keynesian economics with Dalton.

This commitment to the fine tuning of prosperity and its distribution over class struggle and Marxist revolution marks perhaps the final phase of the young Gaitskell's political maturation. A final disavowal of revolutionary rhetoric did not come until 1935, after his return from Austria. Gaitskell had won a Rockefeller scholarship to study in Vienna in 1934. In Vienna, he fell in love with life much as he had done in Nottingham, meaning he also naturally fell in love with the women as well, whose looks he eulogised as having looks 'so high and morals […] at the same time pleasantly loose'. His affections had already been captured back at home by Dora Frost, a divorcee socialist who acted as Gaitskell's lover until they married in 1937, though the relationship was always open – one surviving vestige perhaps of Gaitskell's 'gay and frivolous' days up at Oxford. Little was gay or frivolous about his days in Vienna, however. His stay in the city coincided with a period of reprisals made by the fascist government of Englebert Dollfuss against the Social Democrat Party and the wider socialist movement. In this situation, Gaitskell's resolve hardened – much as it had done during the general strike of 1926. Only whereas 1926 had served as a catalyst for Gaitskell's commitment to socialism and set him on a path that would eventually lead to Marxism, being in Austria in 1934 led Gaitskell to become a committed democratic socialist, anti-fascist and early anti-appeaser.

His actions in Austria, when viewed through the lens of history, could easily have been plucked from the pages of a piece of Cold War pulp fiction. On the ground in Vienna, Gaitskell helped to arrange for the transit of labour leaders to safety in Prague, working with Austrian socialist leaders to set up a smuggling network that helped 170 people flee the fascist regime by the time he returned to London. Gaitskell organised secret meetings and collected money for legal defence for arrested socialists. On one occasion he was even seen by a young Austrian socialist moving compromising papers from his centrally-heated flat to another house with a fire so that he could safely dispose of them. Other times saw him standing on street corners as couriers passed twice before delivering covert correspondence.

By 1935, at the age of 28, Gaitskell had come of age politically. Noel Hall remarked upon his return from Vienna that he would no longer joke about politics. The first tumultuous quarter-century of his life had seen him progress first from the 'ineffective schoolboy' outshone by Dick Crossman at Winchester to the golf-obsessed Oxonian, then to the studious economist of the labour movement and the Marxist academic, before finally settling into position as a fervent democratic socialist and rising star of the intellectual left. It was not an entirely orthodox journey into politics, but it nevertheless provided the foundations for an ascent that would take Gaitskell all the way to Downing Street.

_____________________________________________

1: The full quote reads: 'Mind you, Hugh Gaitskell was a very good dancer. And to me that is far more important than politics in a man'. One cannot help but feel she was perhaps damning him with misdirected praise.

An excellent and, from what I recall of Brivati and Williams, accurate overview of Gaitskell's early life - and on my birthday, no less! I don't suppose you could send me one of those copies of Jenkins' biography of Gaitskell also?