For 3 chapters of this quality, this AAR has a criminally low amount of pages. Subbed!

Forza Italia!

- Thread starter Jape

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Chapter IV

Election of 1863

Election of 1863

King Vittorio Emanuele II

A true party system in the Kingdom of Italy was still coalescing in 1863. Inheriting the political set-up of Sardinia-Piedmont, the ghost of the Conte di Cavour loomed large over the Chamber of Deputies. The Conte established the Liberal faction in Turin during the 1840s, advocating a united (or at least independent) peninsula and moderate reform to avoid revolution. Initially a minority party, the unrest of 1848 catapulted the Conte to the premiership. Weary of radicals like Mazzini and Garibaldi, he allied with the establishment dragging the Liberals to the right and leading to a split with their progressive wing. This sundering created the two dominant factions in the Chamber with the conservative Destra Liberale controlling a comfortable majority thanks to their royal patronage and successful leadership during the unification. The Right was also aided by the nation’s limited franchise.

During this period the Italian electorate numbered roughly 735,000, just over 14% of the adult male population. Dominated by urban rentiers and rural landholders, the voters were inclined to support the moderate ‘King’s Party’. The Sinistra Liberale by comparison were seen as overly truculent, advocating aggressive secularism, revanchist military expeditions and a nationalist trade policy focused around high tariffs. This combative approach was epitomised by the Left’s leader Urbano Rattazzi who had used the failure of the Pasolini Mission and the jingoism of the early days of the Venetian War to expand his support amongst the middle-class. However the bloodshed of the campaign and the Prime Minister’s international stature after Schönbrunn had dulled Rattazzi’s populist message.

This sense of deflation was actively pursued by his opponent. Bettino Ricasoli despite his heightened post-war image was no national hero. A quiet, often dour man he had little interest in the chaotic theatre of the legislature and made no effort to court the press. Reliant (and comfortably so) on the king for his authority he exercised a presidential style of leadership over a cabinet ranging from affable yes men like the foreign minister the Conte Pasolini to arch-rivals like Luigi Carlo Farini at the interior ministry. Marco Minghetti the finance minister was more typical of the middle ground within the Right that appreciated Ricasoli’s competence but had little affection for him.

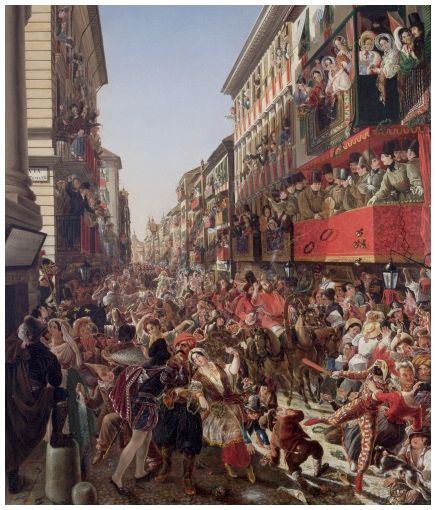

Carnivale - the overwhelming majority of Italians unable to vote, their focus in early 1863 was on the celebratory start of Lent.

This less than stirring message of stability dominated the election of March 1863, which shared little of the carnival atmosphere of 1861, interest mostly limited to the voting minority [1]. Achievements in foreign and military affairs were continuously trumpeted by candidates of the Right across the nation. While this undercut the Left amongst voters it led to some mixed responses from the non-voting majority. Notably in Milan during the campaign General di Bonzo spoke on behalf of the Destra Liberale candidate only to receive verbal abuse and rotten fruit from a group of Venetian War veterans who heckled him as the “Butcher of Treviso”. A taste of things to come.

On domestic affairs as previously mentioned the Right was less confident. A continuing deficit thanks to a large standing army and low taxation of the voting classes [2], Ricasoli advocated support for a growing industrial base, agricultural innovations and crucially free trade in imitation of British liberal policy. Italy’s poor economic stature in comparison to the other European powers however made protectionism a popular panacea, particularly amongst small-scale artisans under threat from large competitors abroad. Rattazzi attempted to make this issue the centrepiece of the election. Travelling across the nation, he crushed numerous free trade advocates in public debates, his rhetorical skill lauded in the Left-leaning papers.

The matter went beyond mere economics. By far the largest interloper into Italian markets was France. In liquor, wheat and textiles, cheap French imports overwhelmed domestic production. The Left was well aware of this and attempted to connect tariffs to a Francophobic foreign policy focused around Emperor Napoleon’s protection of the Papal States. It also stemmed from the Left’s foundation as an anti-Cavour party. The Conte’s arguably slavish connections to Paris during the 1859 War even to the point of ceding historic Italian lands in return for patronage had disgusted men like Rattazzi.

The message proved effective and the Left’s growing support began to worry some on the Right as election day loomed. The Prime Minister’s dedication to free trade was not universal amongst the Destra Liberale. Right protectionists, some ideological others opportunists hoping to once more outflank Rattazzi coalesced around Farini who pressured Ricasoli to change his policy. As ever the “Iron Baron” was unmoved, refusing even to consider a small, symbolic tariff rate. In this he was supported by Minghetti who as finance minister and unspoken leader of ‘neutral’ Right deputies helped halt a party rupture in the midst of the campaign.

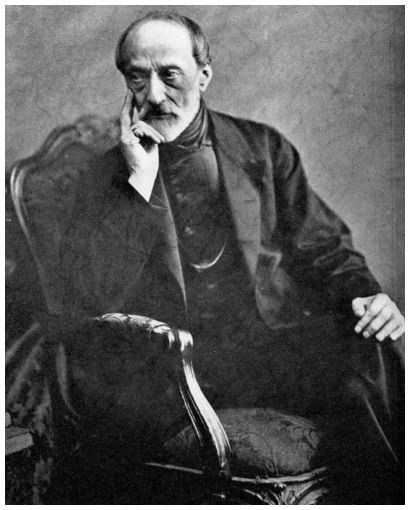

Giuseppe Mazzini - Ally of Garibaldi, staunch republican and leader of the Radicale

The third force in the election was both the smallest in Chamber representation and the most diverse in its political views. The Radicale, also known as the Extreme Left was as its names suggest the home to various strands of revolutionary thought. Led by Giuseppe Mazzini, whose republicans dominated the party, the Radicale included ardent anti-clericalists like the young Felice Cavalotti and early socialists like Agostino Bertani. These groups often held competing views (notably Mazzini was an avowed anti-socialist [3]) yet were united in a common caucus by their hatred of the Liberal parties who they felt had high-jacked popular Italian nationalism in the name of the House of Savoy. Despite being led by one of the fathers of the risorgimento, the Extreme Left struggled to gain support amongst the inherently conservative electorate, while their connections to the Redshirt movement encouraged police suppression orchestrated directly from the Palazzo Reale.

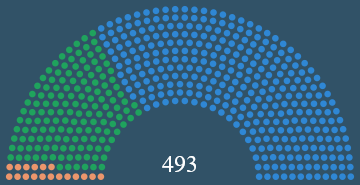

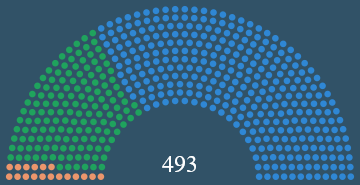

The election results surprised the country. The Right had hoped that the addition of fifty seats from Venetia would lead to moderate gains from a grateful populace and for the party to ‘hold the line’ elsewhere, particularly in their Piedmontese heartlands. However a massive majority created by the totemic Conte di Cavour amidst the joyous foundation of the Italian Kingdom was unlikely to be held, while arguably Ricasoli had waited too long to rely on post-war patriotic fervour. Combined with the economic reality and Rattazzi’s far more energetic campaign, the Right’s representation fell by twenty-five seats while the Left doubled its number of deputies, primarily in Venetia and the former Papal territory of Lazio. The Extreme Left had also made several gains despite its marginal and harassed campaign.

The Destra Liberale returned to government with a majority of over eighty seats, objectively a solid victory. However Ricasoli’s aloof position amongst the Right and the continuing machinations of Farini led many deputies to doubt his suitability to lead them in the long term. The Prime Minister simply lacked a genuine power base in the Chamber and unless he continued to oversee singular successes like Schönbrunn even the King’s favour would not be enough to save him in the cut-throat world of Turin politics.

General Election to the Chamber of Deputies

March 1863

Majority 247

(Note: Additional 50 seats since previous election)

Destra Liberale 329 (-25)

Sinistra Liberale 146 (+73)

Radicale 18 (+4)

March 1863

Majority 247

(Note: Additional 50 seats since previous election)

Destra Liberale 329 (-25)

Sinistra Liberale 146 (+73)

Radicale 18 (+4)

__________

[1] Of course the 1861 general election also coincided with the establishment of a unified Italy which no doubt greatly helped encourage broad popular excitement at the time.

[2] This is for in-game reasons but was also true in Italy IOTL during this period. Taxation was highly regressive with the very rich paying around 3% for most of the late nineteenth century.

[3] Karl Marx called Mazzini a “reactionary ass”.

Last edited:

Intriguing. Clearly in this timeline Bismarck has written off the Austrians as a significant factor in the future - that or political pressure at home forced his hand in making a hard peace with Austria; as you noted the war went on much longer and was certainly bloodier than in OTL.

Somewhat sorry to see Garabaldi go, though I am interested in seeing what will happen this election.

Yes the severity of the war certainly seems to have altered Prussia's goals and that will have major ramifications before the decade is out. Garabaldi has certainly passed the height of his direct influence but his message, of popular and total unification, cannot be silenced and will continue to have effects.

The executive managed to sideline Garibaldi due to him facing the harshest situations, although as you say him returning to the scene is still a possibility, which could be quite the upset.

How the election will now fare is interesting, as it could be decisive to determine the future political landscape of Italy for the years to come. A decisive victory would strengthen Ricasoli, but anything other than that would be highly concerning.

It would, even Ricasoli who is quite sympathetic to Garibaldi is still quietly happy he's out of the picture for now.

Indeed, well as you can see its a step back for the Right but it was hard to see how he could improve on Cavour's dominance. But his lack of friends means that might be small consolation for him...

subbed!

Thank you, glad to have you on board.

For 3 chapters of this quality, this AAR has a criminally low amount of pages. Subbed!

I'm very flattered, thank you very much.

I don't know if it is different in Italy, but I thought carnival was the beginning of LentCarnivale - the overwhelming majority of Italians unable to vote, their focus in March 1863 was on the celebratory end of Lent.

Very nice insight into the state of mind in Italy at the moment, Carnivale and all. I really love that Chamber graph by the way.

how funny it is... here in Argentina we too have a Rattazzi (Italian also) advocating for proteccionism...

Will The Roman Question be solved by Letting his Holiness retain his rightful land as Leader of Christendom? Italy can do without Rome

Just goes to show one should never assume anything in elections. Nothing at all.

Indeed, altough the Right are safe for now. Ricasoli maybe not so.

I don't know if it is different in Italy, but I thought carnival was the beginning of Lent

*Ahem* apologies, I've edited the subtitle thanks for the correction.

Very nice insight into the state of mind in Italy at the moment, Carnivale and all. I really love that Chamber graph by the way.

Thank you, the next update will shed more light on the domestic, and mainly economic state of Italy. Also I think its important to point out even in democracies of this time, for many people politics was a minor consideration because they had little if any involvement. Of course there's other means...

Thank you but there's of my own effort in it. I spent awhile hunting a "hemicycle generator" so I could mimic the lovely graphs you tend to get on wiki election pages. I finally stumbled across this which offers hemicycles and even Westminster-style graphs. You just input the numbers. Very handy.

how funny it is... here in Argentina we too have a Rattazzi (Italian also) advocating for proteccionism...

Ha that is an interesting coincidence.

Will The Roman Question be solved by Letting his Holiness retain his rightful land as Leader of Christendom? Italy can do without Rome

Take a guess. Saying that the current PM Ricasoli is very wary of actually on Rome. As long as Imperial France stays strong I'm sure he's fine

Hey! A Jape AAR that has got beyond the second chapter!

I really want to post the sarcastic 'victory parade' music Malcolm Tucker does in The Thick of It but a simple I know right will probably do. Thanks for jumping on board.

_____________________

Apologies no update right now but thought I'd post so people know I haven't scappered. Next update is 75% done, graphics sorted but I've been quite busy recently, lot of little things. So hopefully update tomorrow but if not definately Sunday.

x

Oh I do love a good election post! It's hard to see Ricasoli lasting much longer, even though any conflict within the Right will be exploited only too happily by the Left.

I wonder how the longer and more difficult Austro-Prussian War will affect the drive towards forming a German Empire. Given the briefly alluded to Hungarian National Convention, will Austria be so wrapped up in its own problems that Prussia feels ready to go for Alsace-Lorraine a bit earlier?

I wonder how the longer and more difficult Austro-Prussian War will affect the drive towards forming a German Empire. Given the briefly alluded to Hungarian National Convention, will Austria be so wrapped up in its own problems that Prussia feels ready to go for Alsace-Lorraine a bit earlier?

Ah, so this is Jape's latest creation? Shall we commence the pool as to how long Jape will go between updates, or whether, after an extended break, will ever come back to it?

All joking aside, welcome back and hopefully things work out for you this time. Though one just has to wonder if you'll make it to 1900 in Victoria 2.

All joking aside, welcome back and hopefully things work out for you this time. Though one just has to wonder if you'll make it to 1900 in Victoria 2.

Chapter V

The Ricasoli Ministry

Finance Minister Marco Minghetti

The Ricasoli Ministry

Finance Minister Marco Minghetti

Having ostensibly consolidated power in the election, Prime Minister Ricasoli and his government began to focus on combating the economic malaise that plagued Italy in the early 1860s. While unmoving on tariffs, Ricasoli proved willing to compromise elsewhere to relieve pressure on the national purse. Following the devastating losses of the Venetian War, the War Ministry under di Bonzo did not attempt to refill the ranks of shattered regiments. Many, particularly those with a non-Sardinian lineage, were quietly disbanded with their survivors consolidated into existing formations. This equated to relatively minor reductions in troop numbers overall, the standing army rebounding to 150,000 soldiers by 1864. Combined with improved army administration (and a noted disregard for naval investment) however, Italy’s gargantuan military budget gradually fell throughout the decade as a percentage of national expenditure.

Incremental changes such as this were central to the Right’s economic policy. The Prime Minister and Finance Minister Minghetti were well aware the Italian economy, a patchwork of regions and former principalities required reform which in turn often required investment. At the same time the national debt and deficit encouraged a reductionist approach along classical liberal lines. Though coming from a local government background, Ricasoli favoured centralised action to overcome the competing customs and interests of the regions. In July 1863 the Chamber passed a series of laws liberalising regulation over industry, mining and crucially farming. Over 60% of Italians during this period worked the land or the sea. Introducing market principles into the often medieval structures of Italian agriculture, the government began to encourage a more commercial approach leading to larger consolidated land holdings.

The ‘Minghetti Reforms’ as they were dubbed proved crucial in invigorating the economy as the continental recession began to ease from 1864. Not only did they encourage production but also private investment in infrastructure, primarily railways. At the time of Unification, Italy was home to little more than 2000km of railways, consisting of small lines around Florence and Naples disconnected from the more extensive networks of Piedmont and Lombardy (and following its annexation Venetia) in the north. The latter half of the decade bore witness to an explosion of railway construction, tripling the length of line by 1870. Though overwhelmingly funded by capitalist investors, the government provided limited financial assistance for less commercially viable lines in Sicily and Sardinia and organised the large, regional trusts known as Società that would dominate the sector into the next century. In line with Ricasoli’s centralising ethos, the Società were created under the auspices of Pietro Bastogi, the Conte di Livorno.

The Minghetti Reforms

A fellow Tuscan and rare close ally of the Prime Minister, di Livorno had connections to the Rothschild banking family. Their Neapolitan branch had fallen out of favour during the risorgimento due to their close ties with the Bourbon regime of the Two Sicilies, leaving their financial interests in the country in doubt. Though lacking their former level of influence [1], the Rothschilds, with encouragement and representation from di Livorno, invested in Italy’s growing railways through the southern Società per le Strade Ferrate Meridionali. In the space of only a few years Naples would be connected to the northern networks via the new coastal Adriatic line running through Ancona and on to Bologna. Although a truly nationwide railway system would not be established until the 1880s, the early years of the Società were crucial in binding Italy geographically, psychologically and economically. Growing transport links and the example of the rail trusts saw an emerging pattern of regionally dominant companies in industry and mining forming oligarchic trusts of their own, often with political connections like di Livorno. Landed interests also followed suit, with latifundia expanding across southern Italy.

Ironically given the incestuous relationship between government and business that would develop in Italy during the late-nineteenth century under the Società model, a central plank of the Ricasoli ministry was the fight against crime and corruption. Unification had seen the Piedmontese Polizia di Stato expanded across the country alongside the Carabinieri gendarmes however funding had not kept pace, leading to a rapid rise in local corruption and organised crime. By 1865 the Finance Ministry was recording a moderate tax surplus allowing for tentative budget increases for law enforcement and the bureaucracy. Tax evasion was a serious drain on the treasury, leading to the reorganisation (in some cases outright purging) of the inland revenue service and its paramilitary arm the Guardia di Finanza [2] alongside the police. Again the Prime Minister used centralised power to combat local problems and within several years notable increases in tax revenue could be traced to the growth in police and bureaucratic strength clamping down on evasion and fraud.

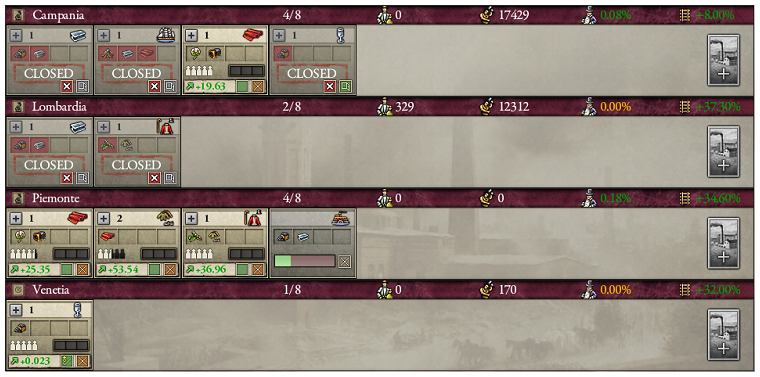

The state of Italian industry, c.1866

Despite these improvements to the exchequer, problems still persisted. Italian industry had begun to grow but in a sputtering and regionally uneven manner. Following the absorption of the Two Sicilies, her once heavily protected native industries in steel and shipbuilding quickly collapsed leaving tens of thousands of workers destitute. Similar episodes played out in Lombardy, both regions having historically had unfettered access to the markets of the Austrian Empire. Interestingly given the importance of French competition in the previous general election, by the late-1860s Piedmontese textiles were the crown jewel of Italian industry. An integrated factory system under the control of the Gruppo Cosenza trust developed, supplying everything from the raw materials to luxury clothing. Lacking protective tariffs the Gruppo Cosenza nevertheless had major clout in the capital. In March 1865 Ricasoli finally caved into pressure from Minghetti to provide subsidies. Initially mocked for its hypocrisy by Left deputies and the dissident press, the policy ensured the growth and development of the domestic textile industry. Similar support was also provided for Vetrerie della compagnia veneziana, Venice’s premier glass-works.

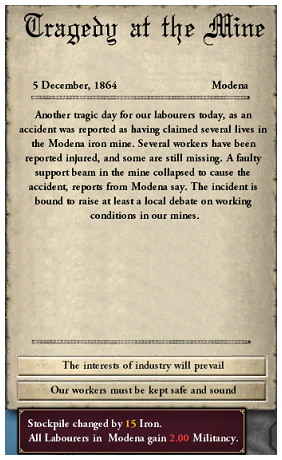

Though subsidies were handed out rarely and officially only to aid viable businesses, the divide between the Piedmontese heartlands and distant Compania were noted by critics. Elsewhere the effects of ‘liberalisation’ were felt. The iron mining industry, previously dominated by local landowners had begun to modernise with larger, more mechanised operations run by dedicated mining companies. Increasing demand during the decade saw major increases in excavation in turn, and ultimately led to a string of tragedies notably Modena in August 1863, Treviso in December 1864 and also at the recently opened Sassari silver mines in Sardinia in February 1865. Accidents and poor working conditions were also noted in the Gruppo Cosenza factories. A lack of interest in safety reform and compensation were the standard responses from both government and employers. Italian trade unionism being both in its infancy and heavily regulated, an increasing number of disenfranchised workers began to make contact with the Radicale and establish pressure groups for voting reform known as the cartisti. The first major cartisti demonstration took place in Turin in February 1866. Though peaceful, the Chamber of Deputies refused to receive the groups’ petition.

The Modena Mine Collapse was one of a series of similar tragedies in the 1860s

Ricasoli’s continued premiership into the middle of the decade had seen him become reliant on Minghetti for stability. Unlike the introverted Prime Minister, Minghetti cultivated a following within the Chamber and beyond. He was renowned as a ‘talent spotter’ and mentored several young politicians who would prove major figures in the coming decades. Initially united by their economic priorities, as well as distaste with Interior Minister Farini’s increasingly overt hunger for power, by 1865 the balance between the two men had begun to shift. Firstly came Farini’s sudden death in February [3]. The Prime Minister could have been forgiven a quiet relief at the news, as it robbed his most ardent critics within the Destra Liberale of a figurehead. However they soon began to search for alternatives and many looked to Minghetti himself. Seen at the start of the decade as a dry if talented financier, Minghetti had used his presence in the legislature and his eponymous reforms to build a following and slowly bring his proteges into junior positions in the government. Due to Ricasoli’s distance from the rank and file and disinterest in self-promotion, the Finance Minister was seen by many backbenchers as the true mastermind of Italy’s steady economic recovery, though his own relative youth limited efforts to have him made premier.

Within Cabinet, the Prime Minister and Minghetti were increasingly at odds over foreign affairs. Ricasoli was a dove on the Roman Question and hoped to use diplomacy with the Pope and Emperor Napoleon to bring the city into the Italian Kingdom gradually. He also took the traditional Cavour line on France, feeling it the natural protector of Italy against the Austrians. In this he was support by Farini's successor at the Interior Ministry, Giovanni Lanza, a long-time ally of Cavour. Intent on avoiding a violent confrontation over Rome, Ricasoli and Foreign Minister Pasolini had returned their focus to Tunisia as a possible colony and outlet for Italian nationalism. Minghetti in contrast felt the annexation of Rome the prime goal of Italian foreign policy and was ambivalent at best towards Paris, rightly believing the Emperor had no interest in ceding his influence over the Papacy. His clique had also seen Schönbrunn as a missed opportunity to cement a formal alliance with the Prussians who lacked a stake in Rome and had greatly reduced the threat posed by Austria. Despite his growing influence, Minghetti proved unable to alter foreign policy due to the King’s approval of the non-confrontational approach to Rome. In Vittorio Emanuele II’s eyes, advocacy of military action against the Pope still amounted to Redshirt radicalism.

Tunisia was the focus of the Ricasoli Ministry's foriegn policy

The consul in Tunis, Pompeo Sulema was already close to the Bey, Muhammad III and with generous funds from Turin had begun increasing Italian influence in the state. The largest European community in Tunis with strong links to the peninsula, Italians had long dominated trade and finance in the country. Mirroring the loss of Algeria and Egypt earlier in the century, the Foreign Minister was confident that building on the preexisting Italian position in Tunis would allow for a gradual detachment of the country from its official master, the Ottoman Empire. This proved a miscalculation. Abdülaziz, Sultan since 1861 was attempting to reinvigorate the Empire, continuing the Tanzimat reforms of his brother, rapidly expanding the navy and strengthening Constantinople’s hold over its subject territories. While Italian economic power in Tunis was a historical norm, news of Sulema’s efforts in the Bey’s court greatly alarmed the Sultan. In October 1865 Italy and Tunisia signed a treaty of friendship, cementing the growth of Italian representation in the native government, with the naval and finance ministries both run almost exclusively by Italians [5]. This proved unacceptable to Abdülaziz who ordered the Italian consulate in Tunis closed and the removal of all Italian citizens from positions of power.

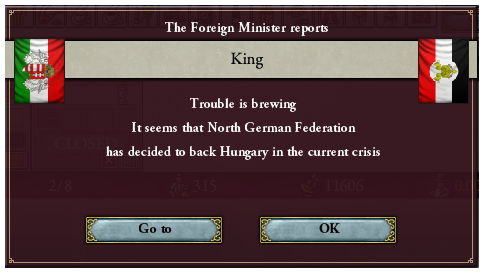

Despite Turin’s focus on Tunisia, Ricasoli and Pasolini were wholly unprepared for the Ottoman response. Militarily, a war in North Africa would be a dangerous undertaking. The navy had languished since unification, a collection of small steam-frigates wholly unsuited to battle the modernised and enlarged Ottoman fleet. Meanwhile the army, though formidable was focused singularly on the Austrian border and the possibility of another war with Vienna. Diplomatically, the government found itself isolated as Constantinople received support from France, its closest European ally and Italy’s rival for influence in Tunisia. Unwilling to antagonise the French and weary of fighting the Ottomans, Ricasoli and the Foriegn Ministry backed down. Originally an area of little interest for the general public, the sudden reversal in Tunis angered many as an affront to Italian dignity. The Conte Pasolini resigned in disgrace at the behest of the King within the week. Ricasoli survived but the Foreign Ministry would be taken over by the young Minghetti protege Emilio Visconti-Venosta, robbing him of a key ally. His crumbling authority now rested on royal support for his Roman policy. The Prime Minister's dogged survival was also helped by the distraction of major events abroad, as the issue of Hungary seemed ready to plunge the entire continent into war.

The Hungarian Crisis, January 1866

__________

[1] The Rothschild’s Naples banking house was closed shortly after the fall of the Two Sicilies for the aforementioned political reasons but they maintained some Italian interests, like the railways, from Frankfurt through various agents like the Conte di Livorno.

[2] Yep, the Italian Finance Ministry has its own gendarme force.

[3] This is historical, in the space of a few months Farini left the Chamber due to illness and died, removing a major figure on the Right.

[4] This connection goes back centuries and at Genoa’s height as a merchant republic, Tunis was an important part of their trading empire.

[5] This is in line with OTL. At one point even Garibaldi, while exiled after the 1848 revolutions, ended up an employee of the Tunisian government, overseeing military and naval reforms.

Last edited:

Oh I do love a good election post! It's hard to see Ricasoli lasting much longer, even though any conflict within the Right will be exploited only too happily by the Left.

I wonder how the longer and more difficult Austro-Prussian War will affect the drive towards forming a German Empire. Given the briefly alluded to Hungarian National Convention, will Austria be so wrapped up in its own problems that Prussia feels ready to go for Alsace-Lorraine a bit earlier?

Of course for Ricasoli to fall, a tenable replacement needs to exist which partly seems the problem.

Its possible. As this update ending implies, Hungary is going to upset the historical applecart somewhat.

Ah, so this is Jape's latest creation? Shall we commence the pool as to how long Jape will go between updates, or whether, after an extended break, will ever come back to it?

All joking aside, welcome back and hopefully things work out for you this time. Though one just has to wonder if you'll make it to 1900 in Victoria 2.

Here's hoping.

Italy still requires more land, Corsica for one. Istria and Dalmatia are nice too I suppose.

Anyway, thought I had subbed to this but apparently not. This is now rectified.

Anyway, thought I had subbed to this but apparently not. This is now rectified.

Mmm, the Ottomans can have powerful friends as well.

In face of this humiliation one thinks it will be hard to keep hold of power.

In face of this humiliation one thinks it will be hard to keep hold of power.

I have to admit it is hard not to sympatize with the Ottomans, even if it has caused you difficulty here. They get beat up so frequently in Victoria 2 I sort of automatically see them as underdogs.

Very insightful update on the political situation at home and abroad. I'm anxious to see what happens in Hungary.

Very insightful update on the political situation at home and abroad. I'm anxious to see what happens in Hungary.

If Hungary secedes, that may lead to a Grossdeutschland under Prussian leadership...