24.3 THE END OF THE GALLIC EMPIRE AND THE DEATH OF AURELIAN.

24.3 THE END OF THE GALLIC EMPIRE AND THE DEATH OF AURELIAN.

After spending the winter in Rome, Aurelian probably went to northern Italy to assume command of the imperial comitatus and vexillationes from the Danubian armies to launch a decisive campaign against the splinter Gallic empire.

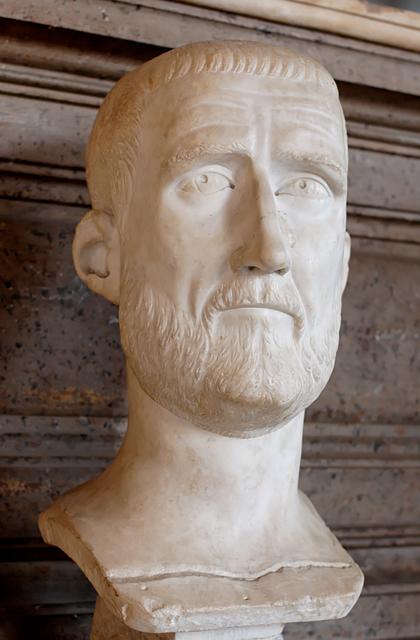

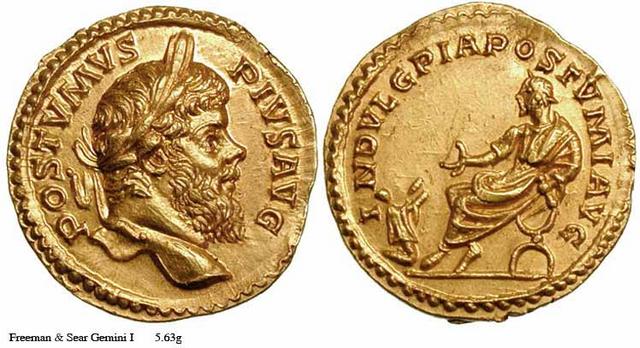

M. Cassianus Latinius Postumus. On the reverse, INDVLG PIA POSTVMI AVG.

As we saw in a previous post, this Gallic empire (Imperium Galliarum) was established by the general of the Rhenish army M. Cassianus Latinius Postumus after murdering Saloninus, son of Gallienus at Colonia Agrippina (modern Cologne) in 259 CE. In the start, Postumus was recognized as augustus by the provinces in Gaul, Hispania, Britain and Raetia. Postumus did not try to impose himself as sole augustus over the whole empire, but instead concentrated on defending and administrating the provinces that acknowledged him. He established his capital at Colonia Agrippina, where he created a parallel senate, with its own consuls and his own Praetorian Guard. His primary objective was to defend the western provinces against the raids of Franks, Alamanni and Saxons, and he seems to have obtained some degree of success, because in 261 CE he took the title Germanicus Maximus. In 263 CE he was able to survive Gallienus’ attack when the latter was severely wounded during a siege and had to abandon the campaign. Later, he managed to convince Aureolus, Gallienus’ senior general, to join him and rebel against his master in 267-268 CE (an event which led to Gallienus’ murder, as we’ve seen).

Ulpius Cornelius Laelianus. On the reverse, TEMPORVM FELICITAS.

But he would too in due turn suffer the same fate as Gallienus. In February or March 268, the legate of Upper Germania Ulpius Cornelius Laelianus (or Lollianus) had himself proclaimed augustus by his troops at Mogontiacum (modern Mainz) which included Legio XXII Primigenia and several auxiliary units (the other legion in the province Legio VIII Augusta based at Argentorate [modern Strasbourg] did not join the rebellion). Postumus reacted quickly and besieged Mogontiacum, where Laelianus’ men eventually killed their own commander and sent his head to Postumus. As Mogontiacum had surrendered peacefully, Postumus forbid his troops to sack the city; this angered his men, who murdered him. The murder of Postumus was a fatal blow for the Gallic empire, because in the following confusion (which seems to have coincided in time with the murder of Gallienus and the rise to the purple of Claudius Gothicus), Hispania and Raetia acknowledged Claudius Gothicus as the legitimate augustus and rejoined the “central” Roman empire. Meanwhile, the Rhenish legions elected a certain Marcus Aurelius Marius as augustus, but he too was murdered (unknown circumstances and causes) after a brief period of time.

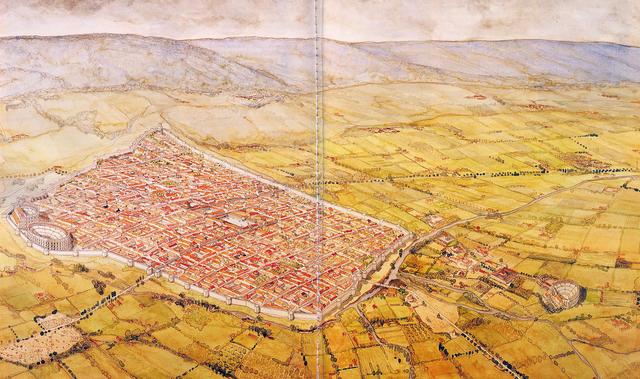

Marcus Piavonius Victorinus. On the reverse, LAETITIA AVG.

After Marius’ death a certain Marcus Piavonius Victorinus rose to the purple. According to the SHA, he had been the “right hand man” of Postumus; I should add though that all our knowledge about these ephemeral Gallic emperors comes from the very unreliable HA and from numismatics, so details are very fuzzy. At around the same time that Victorinus became emperor, Claudius Gothicus seems to have sent troops across the Alps into Gallia Narbonensis; it’s unknown if this was a campaign of conquest or if the province rebelled and Claudius Gothicus sent troops in its help; in any case the province seems to have fallen firmly in the hands of Claudius. Perhaps prompted by the revolt of Narbonensis, the large city of Augustodunum (modern Autun) in the province of Gallia Lugdunensis also rebelled and acknowledged Claudius Gothicus as the legitimate augustus. This time though Claudius seems to have been unable (or according to Hartmann unwilling) to send military help, and Victorinus moved against the city. In the summer of 270 CE, Augustodunum was taken by Victorinus’ troops after a seven months long siege, and they plundered and burned the city so thoroughly that archaeological digs have revealed that it never recovered from the destruction inflicted. According to the SHA, Victorinus was murdered in late 270 CE or early 271 CE by his general Attitianus, whose wife (according to the SHA) had been “seduced” by the emperor.

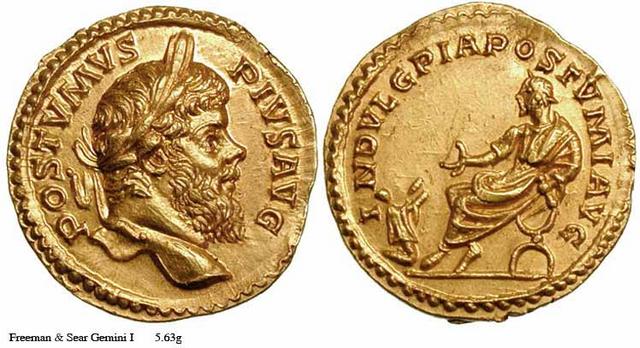

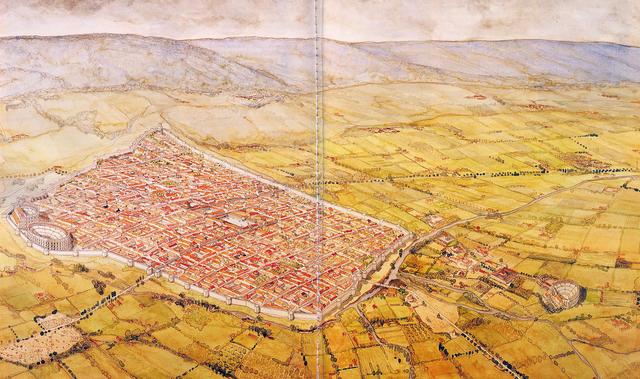

Restitution of the Gallo-Roman city of Augustodunum by the French architect and archaeologist Jean-Claude Golvin.

The next emperor in this Gallic carrousel was Gaius Pius Esuvius Tetricus (gotta love that name ) until then governor of the rich province of Gallia Aquitania, who was able to pay a juicy donativum to the troops and became the new augustus in early spring of 271 CE. Towards the end of the same year, he moved the capital to Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier) and in 273 CE he raised his son Tetricus the Younger to the rank of “junior” augustus.

) until then governor of the rich province of Gallia Aquitania, who was able to pay a juicy donativum to the troops and became the new augustus in early spring of 271 CE. Towards the end of the same year, he moved the capital to Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier) and in 273 CE he raised his son Tetricus the Younger to the rank of “junior” augustus.

Gaius Pius Esuvius Tetricus.

By this time though Aurelian was back in Italy ready to finish the Gallic empire once and for all. As we’ve seen, he controlled both Raetia and Narbonensis, so he had control over the Alpine passes. Either at the end of 273 CE or in early 274 CE, Aurelian’s army crossed the Alps and marched straight north towards Augusta Treverorum. Tetricus marched south with his army and the clash happened near Duracatalaunum/Catalaunum (the modern city of Châlons-en-Champagne). According to some ancient sources, Tetricus was unwilling to fight against Aurelian but he feared his men’s reaction if he tried to surrender, so he opened secret negotiations with Aurelian. The result of these negotiations was that Tetricus deployed deliberately his army in an exposed position (previously accorded with Aurelian), who then proceeded to annihilate it. The tale seems quite improbable, but these same sources state that Tetricus and his son were very well treated by Aurelian after his victory: they were displayed in Aurelian’s spectacular triumph in Rome that very same year, but they were both well treated, kept their lives and estates and Tetricus was appointed corrector Lucaniae et Bruttiorum in southern Italy, where he was allowed to settle down. Some modern scholars are very skeptical about this tale and believe it to be an echo of Aurelian’s propaganda, but right until now there’s no specific proof that has allowed historians to glimpse an alternate storyline.

The task of reuniting the empire was complete and had been achieved in less than four years, so now Aurelian took a new string of titles, even grander than all the previous ones: PACATOR ORBIS (“pacifier of the world”), RESTITVTOR ORBIS (“restorer of the world”) and RESTITVTOR SAECVLI (“restorer of the century”). After his success in Gaul, Aurelian returned to Rome, where according to the HA he celebrated an extravagant triumph (the triumph probably happened, but scholars consider that all the details about it provided by the HA are once more fabrications). During this last stay in Rome, he probably put in motion his currency reform, one of the most controversial aspects of his reign among modern scholars (ancient authors ignore it completely). Some scholars like David S. Potter consider it an unmitigated failure: according to the evidence provided by Egyptian papyri (which is the only one that we really have), the start of the massive inflation of prices coincided exactly in time with this reform. But others like D. Hollard see it in a much more positive light and consider it a (relative) success.

According to D. Hollard’s 1995 paper La crise de la monnaie dans l’empire romain au IIIe siècle, Aurelian’s reform of the currency consisted in a stabilization of the weight of the aureus (at a high precious metal content, over 90%) at 1/50th of a Roman pound (in comparison, the Augustan aureus weighted 1/40th of a Roman pound), that is 6.55 g. But the essential innovation concerned the antoninianus. According to Hollard, its weight was stabilized at 1/84th of a Roman pound (3.90 g) and most importantly: Aurelian fixed the proportion of silver it contained at 1 part of silver for 20 parts of copper (about 4,8% of silver) and had it stamped on each coin with the mark XXI (or its Latin [XX.I, XX ET I] and Greek [KA, K.A] variants). The new reformed antoninianus (called aurelianus by numismatists) was equivalent initially to four denarii or two ancient antoniniani, with the denarius remaining as the accounting unit. According to Hollard’s interpretation, this initial equivalence was not intended to be immutable, but the new aurelianus’ value in denarii was expected to fluctuate. Potter considers this to be the reason for the reform’s failure: Aurelian had created a coin that was not tied to the accounting unit (the denarius) but which was still tied to the golden aureus, and probably at a totally artificial value. In other words: the aurelianus was a fiduciary coin, and this was an innovation that came almost seventeen centuries too early. An added problem according to Potter (Hollard does not mention it) is that Aurelianus seems to have intended his currency reform partly as a political measure: he wanted to take out of circulation all the coins issued by the Gallic and Palmyrene regimes, and substitute them with his new coin. But this would have crashed with the harsh reality that at a 4,8% silver content, his coins in most cases were of a lower law than older Palmyrene and Gallic issues, and so many people must have refused to exchange them.

Aurelian also took steps in the field of internal administration, as we’ve seen in the previous post in his arrangements for the East. And he also tried to strengthen the authority of the figure of the emperor by reinforcing its theocratic features. In this Aurelian was not an innovator, because already Gallienus had started this trend; in some of his aureus he is associated directly to Hercules, and in others he appears with the legend DEO AVGVSTO. Aurelian went further than this. On one side, he publicly endorsed the cult of Sol Invictus in his coinage (and also with his building program), and in some coins issued towards the end of his reign he’s addressed as dominus et deus. And according to the IV century CE Epitome de Caesaribus, he was the first emperor to wear a golden diadem and garments embroidered with gold and precious stones. According to another IV century CE source (Eusebius of Caesarea) by the time of his death he was about to launch a new persecution against Christians, as he saw them as obstacles in the path of his religious policies.

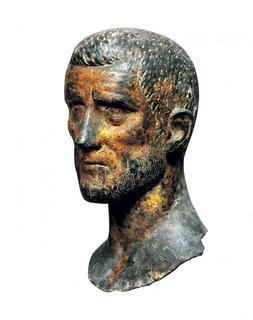

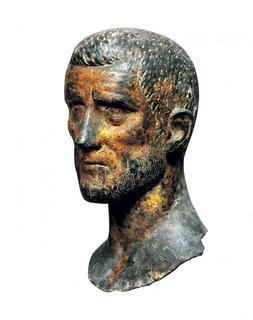

Possible head of Aurelian (archaeologists are not sure, it could also be Claudius Gothicus) in gilded bronze, found at Brixia (modern Brescia) in northern Italy; it was possibly attached to a cult statue of the emperor in one of the temples of the city's capitolium.

According to Eusebius, Aurelian’s murder in October of 275 CE was thus an act of divine justice. Aurelian left Rome that spring towards Gaul, and then went to Raetia to deal with some incursions by the Alamanni, who were besieging the provincial capital Augusta Vindelicorum (modern Augsburg). From there, the emperor went to Thrace; it’s unclear the reason for his travel there. Some authors speculate that maybe he wanted to launch a campaign of reprisal against the Sasanians, while Hartmann thinks that perhaps there were again problems with the Goths in the lower Danube. That October, Aurelian was murdered by his guardsmen in a conspiracy orchestrated by one of his secretaries (a certain Eros according to the SHA) who had fallen in disgrace with the emperor and wanted to avoid reprisals; the murder took place at Caenophrurium in Thrace, along the road from Perinthus to Byzantium. As Aurelian had no sons and had given no signals of being willing to start a dynasty (he had appointed no heirs), the choice of a new augustus fell on the army (as usual).

After spending the winter in Rome, Aurelian probably went to northern Italy to assume command of the imperial comitatus and vexillationes from the Danubian armies to launch a decisive campaign against the splinter Gallic empire.

M. Cassianus Latinius Postumus. On the reverse, INDVLG PIA POSTVMI AVG.

As we saw in a previous post, this Gallic empire (Imperium Galliarum) was established by the general of the Rhenish army M. Cassianus Latinius Postumus after murdering Saloninus, son of Gallienus at Colonia Agrippina (modern Cologne) in 259 CE. In the start, Postumus was recognized as augustus by the provinces in Gaul, Hispania, Britain and Raetia. Postumus did not try to impose himself as sole augustus over the whole empire, but instead concentrated on defending and administrating the provinces that acknowledged him. He established his capital at Colonia Agrippina, where he created a parallel senate, with its own consuls and his own Praetorian Guard. His primary objective was to defend the western provinces against the raids of Franks, Alamanni and Saxons, and he seems to have obtained some degree of success, because in 261 CE he took the title Germanicus Maximus. In 263 CE he was able to survive Gallienus’ attack when the latter was severely wounded during a siege and had to abandon the campaign. Later, he managed to convince Aureolus, Gallienus’ senior general, to join him and rebel against his master in 267-268 CE (an event which led to Gallienus’ murder, as we’ve seen).

Ulpius Cornelius Laelianus. On the reverse, TEMPORVM FELICITAS.

But he would too in due turn suffer the same fate as Gallienus. In February or March 268, the legate of Upper Germania Ulpius Cornelius Laelianus (or Lollianus) had himself proclaimed augustus by his troops at Mogontiacum (modern Mainz) which included Legio XXII Primigenia and several auxiliary units (the other legion in the province Legio VIII Augusta based at Argentorate [modern Strasbourg] did not join the rebellion). Postumus reacted quickly and besieged Mogontiacum, where Laelianus’ men eventually killed their own commander and sent his head to Postumus. As Mogontiacum had surrendered peacefully, Postumus forbid his troops to sack the city; this angered his men, who murdered him. The murder of Postumus was a fatal blow for the Gallic empire, because in the following confusion (which seems to have coincided in time with the murder of Gallienus and the rise to the purple of Claudius Gothicus), Hispania and Raetia acknowledged Claudius Gothicus as the legitimate augustus and rejoined the “central” Roman empire. Meanwhile, the Rhenish legions elected a certain Marcus Aurelius Marius as augustus, but he too was murdered (unknown circumstances and causes) after a brief period of time.

Marcus Piavonius Victorinus. On the reverse, LAETITIA AVG.

After Marius’ death a certain Marcus Piavonius Victorinus rose to the purple. According to the SHA, he had been the “right hand man” of Postumus; I should add though that all our knowledge about these ephemeral Gallic emperors comes from the very unreliable HA and from numismatics, so details are very fuzzy. At around the same time that Victorinus became emperor, Claudius Gothicus seems to have sent troops across the Alps into Gallia Narbonensis; it’s unknown if this was a campaign of conquest or if the province rebelled and Claudius Gothicus sent troops in its help; in any case the province seems to have fallen firmly in the hands of Claudius. Perhaps prompted by the revolt of Narbonensis, the large city of Augustodunum (modern Autun) in the province of Gallia Lugdunensis also rebelled and acknowledged Claudius Gothicus as the legitimate augustus. This time though Claudius seems to have been unable (or according to Hartmann unwilling) to send military help, and Victorinus moved against the city. In the summer of 270 CE, Augustodunum was taken by Victorinus’ troops after a seven months long siege, and they plundered and burned the city so thoroughly that archaeological digs have revealed that it never recovered from the destruction inflicted. According to the SHA, Victorinus was murdered in late 270 CE or early 271 CE by his general Attitianus, whose wife (according to the SHA) had been “seduced” by the emperor.

Restitution of the Gallo-Roman city of Augustodunum by the French architect and archaeologist Jean-Claude Golvin.

The next emperor in this Gallic carrousel was Gaius Pius Esuvius Tetricus (gotta love that name

Gaius Pius Esuvius Tetricus.

By this time though Aurelian was back in Italy ready to finish the Gallic empire once and for all. As we’ve seen, he controlled both Raetia and Narbonensis, so he had control over the Alpine passes. Either at the end of 273 CE or in early 274 CE, Aurelian’s army crossed the Alps and marched straight north towards Augusta Treverorum. Tetricus marched south with his army and the clash happened near Duracatalaunum/Catalaunum (the modern city of Châlons-en-Champagne). According to some ancient sources, Tetricus was unwilling to fight against Aurelian but he feared his men’s reaction if he tried to surrender, so he opened secret negotiations with Aurelian. The result of these negotiations was that Tetricus deployed deliberately his army in an exposed position (previously accorded with Aurelian), who then proceeded to annihilate it. The tale seems quite improbable, but these same sources state that Tetricus and his son were very well treated by Aurelian after his victory: they were displayed in Aurelian’s spectacular triumph in Rome that very same year, but they were both well treated, kept their lives and estates and Tetricus was appointed corrector Lucaniae et Bruttiorum in southern Italy, where he was allowed to settle down. Some modern scholars are very skeptical about this tale and believe it to be an echo of Aurelian’s propaganda, but right until now there’s no specific proof that has allowed historians to glimpse an alternate storyline.

The task of reuniting the empire was complete and had been achieved in less than four years, so now Aurelian took a new string of titles, even grander than all the previous ones: PACATOR ORBIS (“pacifier of the world”), RESTITVTOR ORBIS (“restorer of the world”) and RESTITVTOR SAECVLI (“restorer of the century”). After his success in Gaul, Aurelian returned to Rome, where according to the HA he celebrated an extravagant triumph (the triumph probably happened, but scholars consider that all the details about it provided by the HA are once more fabrications). During this last stay in Rome, he probably put in motion his currency reform, one of the most controversial aspects of his reign among modern scholars (ancient authors ignore it completely). Some scholars like David S. Potter consider it an unmitigated failure: according to the evidence provided by Egyptian papyri (which is the only one that we really have), the start of the massive inflation of prices coincided exactly in time with this reform. But others like D. Hollard see it in a much more positive light and consider it a (relative) success.

According to D. Hollard’s 1995 paper La crise de la monnaie dans l’empire romain au IIIe siècle, Aurelian’s reform of the currency consisted in a stabilization of the weight of the aureus (at a high precious metal content, over 90%) at 1/50th of a Roman pound (in comparison, the Augustan aureus weighted 1/40th of a Roman pound), that is 6.55 g. But the essential innovation concerned the antoninianus. According to Hollard, its weight was stabilized at 1/84th of a Roman pound (3.90 g) and most importantly: Aurelian fixed the proportion of silver it contained at 1 part of silver for 20 parts of copper (about 4,8% of silver) and had it stamped on each coin with the mark XXI (or its Latin [XX.I, XX ET I] and Greek [KA, K.A] variants). The new reformed antoninianus (called aurelianus by numismatists) was equivalent initially to four denarii or two ancient antoniniani, with the denarius remaining as the accounting unit. According to Hollard’s interpretation, this initial equivalence was not intended to be immutable, but the new aurelianus’ value in denarii was expected to fluctuate. Potter considers this to be the reason for the reform’s failure: Aurelian had created a coin that was not tied to the accounting unit (the denarius) but which was still tied to the golden aureus, and probably at a totally artificial value. In other words: the aurelianus was a fiduciary coin, and this was an innovation that came almost seventeen centuries too early. An added problem according to Potter (Hollard does not mention it) is that Aurelianus seems to have intended his currency reform partly as a political measure: he wanted to take out of circulation all the coins issued by the Gallic and Palmyrene regimes, and substitute them with his new coin. But this would have crashed with the harsh reality that at a 4,8% silver content, his coins in most cases were of a lower law than older Palmyrene and Gallic issues, and so many people must have refused to exchange them.

Aurelian also took steps in the field of internal administration, as we’ve seen in the previous post in his arrangements for the East. And he also tried to strengthen the authority of the figure of the emperor by reinforcing its theocratic features. In this Aurelian was not an innovator, because already Gallienus had started this trend; in some of his aureus he is associated directly to Hercules, and in others he appears with the legend DEO AVGVSTO. Aurelian went further than this. On one side, he publicly endorsed the cult of Sol Invictus in his coinage (and also with his building program), and in some coins issued towards the end of his reign he’s addressed as dominus et deus. And according to the IV century CE Epitome de Caesaribus, he was the first emperor to wear a golden diadem and garments embroidered with gold and precious stones. According to another IV century CE source (Eusebius of Caesarea) by the time of his death he was about to launch a new persecution against Christians, as he saw them as obstacles in the path of his religious policies.

Possible head of Aurelian (archaeologists are not sure, it could also be Claudius Gothicus) in gilded bronze, found at Brixia (modern Brescia) in northern Italy; it was possibly attached to a cult statue of the emperor in one of the temples of the city's capitolium.

According to Eusebius, Aurelian’s murder in October of 275 CE was thus an act of divine justice. Aurelian left Rome that spring towards Gaul, and then went to Raetia to deal with some incursions by the Alamanni, who were besieging the provincial capital Augusta Vindelicorum (modern Augsburg). From there, the emperor went to Thrace; it’s unclear the reason for his travel there. Some authors speculate that maybe he wanted to launch a campaign of reprisal against the Sasanians, while Hartmann thinks that perhaps there were again problems with the Goths in the lower Danube. That October, Aurelian was murdered by his guardsmen in a conspiracy orchestrated by one of his secretaries (a certain Eros according to the SHA) who had fallen in disgrace with the emperor and wanted to avoid reprisals; the murder took place at Caenophrurium in Thrace, along the road from Perinthus to Byzantium. As Aurelian had no sons and had given no signals of being willing to start a dynasty (he had appointed no heirs), the choice of a new augustus fell on the army (as usual).

Last edited: