23.4 IRAN UNDER ŠĀBUHR I. ŠĀBUHR I’S COURT, FAMILY AND SUCCESSION.

23.4 IRAN UNDER ŠĀBUHR I. ŠĀBUHR I’S COURT, FAMILY AND SUCCESSION.

The essential (and practically only) source about the family and court of Šābuhr I is again the ŠKZ. This document is a long rock inscription which can be divided in the following blocks (some of which have been already covered in this thread as one of the main sources to reconstruct Sasanian political history during the III century):

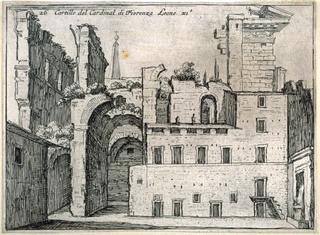

Triumphal rock relief known as "Bishapur III" showing Šābuhr I surrounded by his army and courtiers.

The first thing that can be noticed by comparing these three lists is that Šābuhr I had four male sons who were named kings over different parts of the empire, but that they are not named in the same order in all lists, and some are even omitted in some of them. Let’s see first the first list, that of sacred fires:

Scholars consider that in this first list Šābuhr I named his progeny by the order of his affection towards them. First comes his daughter Ādur-Anāhīd, who was obviously not a candidate for succession; it’s interesting nevertheless that she carried the title “queen of queens”; that must imply that Šābuhr I was quite fond of her.

Among his sons, Hormazd-Ardaxšīr comes the first. He enjoys also a very special title, that of Great King of Armenia (wuzurg šāh arminān). No other sub-king in the empire, not even if they were members of the House of Sāsān, enjoyed the title of “Great King”. Scholars suppose that it was created purposefully after the annexation of Armenia in order to remark the exceptional importance that this kingdom had for the Sasanians, and that because of its exceptionality Šābuhr I would have conceived it as the title to be carried by his heir apparent. As we have seen before, Hormazd-Ardaxšīr is also the only one amongst Šābuhr I’s sons whose participation in the campaigns of his father is attested in the sources. He would succeed his father as šāhān šāh as Hormazd I.

The following one among Šābuhr I’s sons named in this first list is Šābuhr king of Mesān (mesān šāh). Little or nothing is known about him, except that according to (very dubious) Manichaean texts, he was converted by Mani to the Manichaean religion.

The last of Šābuhr I’s sons to whom a fire is dedicated is Narsē; he must’ve been something of a special case too because he’s called “the Mazdayasnian Narsē”, which must’ve been a sign that he was seen as especially pious and attached to the Mazdean tradition. He also boasted an impressive array of titles, “king of India, Sakestān and Turān to the seashore” (šāh hind sagestān ud tūrestān). Traditionally, before the conquest of Armenia the title of king of Sakestān (or “king of the Sakas”) had also been viewed as a prerogative of the heir apparent. Eventually, twenty years after his father’s death Narsē would also rise to the throne of the Sasanian empire.

Let’s look now though at the second list, which offer some puzzling revelations based on the order in which its members appear listed (scholars are quite sure that the order of precedence in inscriptions or other official documents was not something random, but that it followed a strict order dictated by social hierarchy or royal favor):

This list is quite longer, and the first thing to be noted is that first of all Šābuhr I notes down his ancestors in chronological order: Sāsān, Pābag, Šābuhr (eldest brother of Ardaxšīr I) and finally Ardaxšīr I. The order of precedence of the three following names, queens Xvarrānzēm, Ādur-Anāhīd and Dēnag, is unclear. From the previous list we know that Ādur-Anāhīd was his daughter, and from the list of the relatives and courtiers of Ardaxšīr I we know that a certain Dēnag had been the mother of king Pābag (and so she was Šābuhr I’s great-grandmother) and that another Dēnag, who appears also listed in the list of Ardaxšīr I’s courtiers as “queen of queens” (bānbišnān bānbišn) and as “daughter of Pābag, the king”. According to some scholars (like P.Gignoux), she must’ve been Ardaxšīr I’s sister and also his wife (but not the mother of Šābuhr I), in an example of the type of consanguineous marriage favored by the Zoroastrian tradition and priesthood (xwēdōdah), but other scholars (like A.Maricq and J.Harmatta) believe that the title of “queen of queens” reflected social rank rather than family status, and that thus it was no indications that the bearer of the title was the wife of the ruling šāhān šāh.

Thus, Dēnag as sister of Ardaxšīr I bore the title of “queen of queens” under her brother’s (and perhaps husband) rule, but later she lost it, and “dropped” in hierarchy to be listed after her grand-niece Ādur-Anāhīd, who wore the title under Šābuhr I. The same rationale and doubts applied to Dēnag stand also in Ādur-Anāhīd’s case: was she also his father’s wife? Nothing else is known about Xvarrānzēm and about the title she enjoyed (“queen of the kingdom”, šahr bānbišn).

After these three queens, we find a surprise. The first man listed is a certain Bahrām, king of Gēlān. And scholars have been able to identify this Bahrām with none other than Bahrām I, who succeeded Hormazd I as šāhān šāh in 273 CE. He’s followed by the other three kings that we already saw in the previous list: Šābuhr, king of Mesān, Hormazd- Ardaxšīr, great king of Armenia; and Narsē, king of Sakestān. Given that these three kings were Šābuhr I’s sons, it seems logical to assume that Bahrām, king of Gēlān was also a son of Šābuhr I. Scholaly consensus about the different order in this list for Šābuhr I’s sons in this second list is that in this one they appear listed by order of birth, while in the first list they were deliberately listed by Šābuhr I according to his preferences. This is further reinforced because Bahrām appears already depicted as a little child in the investiture relief of Ardaxšīr I at Naqš-e Rajab which is dated to shortly after 224 CE. Thus, by order of birth Bahrām was the first-born son, but he was clearly not his father’s favorite, to the point that Šābuhr I did not even include him in the list of people to whom sacred fires would be dedicated. Šābuhr, king of Mesān was the second-born son, Hormazd- Ardaxšīr, great king of Armenia was the third-born son and Narsē, king of Sakestān was the youngest.

Investiture relief of Ardaxšīr I at Naqš-e Rajab. Šābuhr I stands behind his father to the left of the image, while the future Bahrām, king of Gēlān is the little child in the middle, which is depicted in front of an image of Hercules/Herakles/Verethragna, which is the Iranian warrior god after whom he was named (Avestan Verethragna became Bahrām in Middle Persian).

Clearly, the order in which Šābuhr I’s sons appear listed in the first list is the order of preference which they held on their father’s eyes, and the third son Hormazd-Ardaxšīr was Šābuhr I was his favorite son. Therefore, he named him Great King of Armenia and invested him as his heir apparent, while the eldest son Bahrām was relegated into obscurity and provided only with the rather secondary title of king of Gēlān (a mountainous area in northern Iran in the Alborz mountains), which ranked clearly under the kingdoms held by his three other brothers. This decision of Šābuhr I was potentially problematic, but it seems that he was strong and respected enough as a king that it was enacted after his death, although the short reign of Hormazd-Ardaxšīr caused the problem to reappear just a year after his father’s decease.

After these four kings, the remaining royal relatives are listed in strict hierarchical order: first the wives of te kings (in the same order of precedence as their husbands) and then their sons and daughters, also following the same order of precedence as their fathers (curiously, the kings have precedence over the queens, but sons and daughters are listed together). Immediately before this listing of grandsons and granddaughters of Šābuhr I there are though some characters named that probably include siblings, cousins and other relatives of Šābuhr I which in the hierarchy of the court ranked higher than his grandchildren. Two among these characters are worth mentioning. One is “Pērōz, the (royal) prince”, who could be the same Pērōz who appears in Manichaean sources as a brother of Šābuhr I and one of Mani’s followers and protectors. The other character is “Mirrōd, the lady, mother of king of kings Šābuhr”; this is the same “Lady Myrod” that appears in later Islamic sources as the mother of Šābuhr I. She is quite down in the list’s hierarchy despite being the king’s mother, which has led scholars to believe that she was probably a concubine of Ardaxšīr I and hot a royal spouse.

Let’s look now at the third and final list of courtiers, which is much longer than the two previous lists:

This last list does not include any members of the royal family which had been already named in the second list. It does include though other sub-kings of the empire, some of whom we know were Šābuhr I’s brothers. This is the case of the first two kings listed, Ardaxšīr, king of Nodšēragān and Ardaxšīr, king of Kirmān. Hamazāsp, king of Viruz (ancient Iberia, modern Georgia) was not a member of the House of Sāsān, and so he’s listed in the last place among the kings. The list follows a strict order according to social hierarchy; first the šahrdārān (sub-kings), then the wispuhrān (members of the royal house without a kingly title), then the higher officials of the army and the civilian administration, then the wuzurgān (grandees), then the āzādān (lesser nobility) and then all the rest.

So, after the šahrdārān quoted above, we have the wispuhrān listed: Valāš, Sāsān, Narsē son of Pērōz and Narsē son of Šābuhr. Then the list goes on with the upper members of the political and military apparatus: Šābuhr, the bidaxš, Pābag, the hazāruft (or hazārbed) and Pērōz the aspbed. It’s highly probable that these three gentlemen were also members of the wuzurgān.

The list then continues with the wuzurgān; obviouly it doesn’t include all the wuzurgān of Iran, only those who were in the good graces of Šābuhr I; like under his father, the list includes members of the Sūrēn and Kārin clans. They are listed in this order:

An important issue with these lists is that, as you can see, they’re quite exhaustive, but neither the one for the relatives and courtiers of Ardaxšīr I nor the three lists for the relatives and courtiers of Šābuhr I name a kušān šāh. In a previous post I wrote about the conquest of the Kushan empire by Ardaxšīr I and Šābuhr I and the discovery of coins minted in Marv bearing in Bactrian language and script the name of a certain Ardašaro Košano. The problem is that, as you can see, there’s no trace of him in the ŠKZ, or of any descendant. The first certain mention of a kušān šāh in a Sasanian document is in the Paikuli inscription of Narsē, dated to ca. 293 CE. This kušān šāh could be Pērōz 1 (Note: because the imperial Sasanians and the Kushano-Sasanians used the same names, there’s a useful convention of using Roman numbers for the imperial Sasanians and Arabic numbers for Kushano-Sasanian kings), who issued coins during the late III and early IV centuries CE in Balkh, Herat and Gandhāra. It’s still unclear which was the exact family relationship between this minor Sasanian branch and the main branch in Iran.

As for the personality of Šābuhr I, little can be said about it from the surviving evidence. The Šāh-nāmah (which confuses and mixes the historical figures of Šābuhr I and Šābuhr II) gives a glittering report of this mythical Šābuhr as a mirror of human virtues to the point that it sounds quite fanciful; the main Islamic-era account by Tabarī (who at lest does not confuse both kings) offers a similar image. On the other side, most Graeco-Roman, western Syriac and Armenian sources paint him as a bloodthirsty barbarian. Both portraits are obviously little more than a caricature.

He was not exactly a pacifist or a humanitarian about that much we can be sure. His own account of his two in invasions of Roman territory proudly state that his men looted, killed and pillaged everywhere they could, and that was standard behavior for armies in the III century. Some Armenian, Syriac and Greek accounts also paint a ghastly picture of the way the vast columns of Roman captives were driven by Šābuhr I’s soldiers “like cattle” back to Ērānšāhr, which again seems like standard behavior of his times (one just needs to look at the Aurelian column in Rome to see how Roman soldiers behaved in enemy territory). But getting such vast numbers of people back alive (at least enough of them to populate several entire cities and conduct large-scale public works) means that the deportation was at least well organized and that it was not just done for cruelty’s sake.

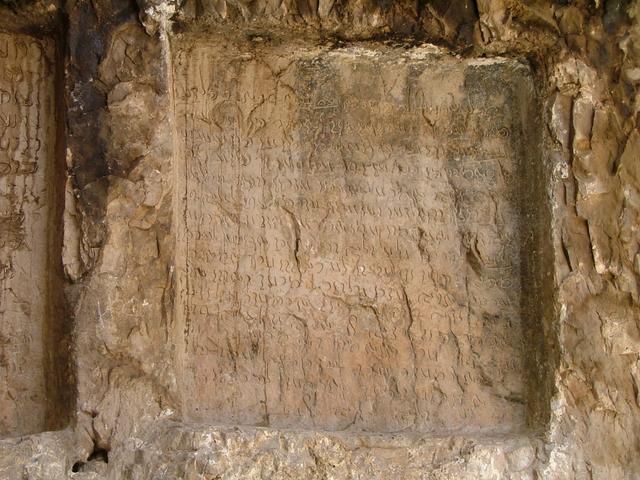

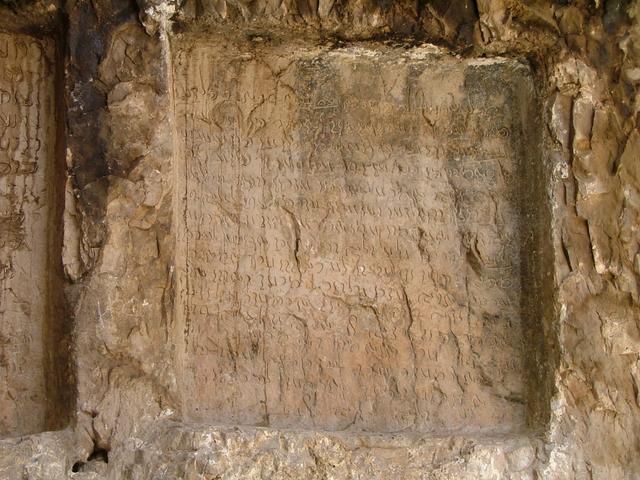

Rock inscription of Šābuhr I at Hājjiābad in Fārs.

We can also be fairly sure that he was a boastful and prideful individual, judging by the inordinate amount of rock-reliefs and inscriptions he’s left behind. In several of them he’s shown as an accomplished fighter, and probably that’s more than simple propaganda. The Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah victory relief depicting the victory of the Sasanians at Hormozdgan shows bot Ardaxšīr I and Šābuhr I in battle garment and engaged in fight. Although it’s quite improbable that Ardaxšīr I killed the last Arsacid king Ardawān V with his own hands and that his son Šābuhr did the same with the latter’s “chief minister”, it’s quite probable that both men took part personally in battles in leading their men. Islamic sources depict Ardaxšīr I as an accomplished bowman, and as the inventor of the “Sasanian draw” that had not been used in Iran before him, and which favored a quicker delivery of arrows. Šābuhr I was also an accomplished bowman, and the fortuitous finding of an inscription at Hājjiābad in Fārs dated to the last decade of his reign offers us a glimpse that in his old age he was still an active man, capable of feats of archery:

Obviously, we can’t judge today how far did Šābuhr I shoot that arrow, but clearly he judged the feat important enough that he had the inscription also repeated about a hundred km. northwest of the first, at Tang-e Borāq in an identical archeological context, on the rock of a grotto, and that he made clear that the feat had been achieved “before the sovereigns, and the princes of the blood and the grandees and the nobility”. It’s worth noting that no other Sasanian king has left a similar inscription boasting of an “athletic” achievement (or at least nothing similar has been found up to this date).

Šābuhr I, šāhān šāh ērān ud anērān, died at Bīšāpūr in May 272 CE and was peacefully succeeded by the heir he had designated, the Great King of Armenia Hormazd-Ardaxšīr, who became the new king of kings of Iranians and non-Iranians as Hormazd I.

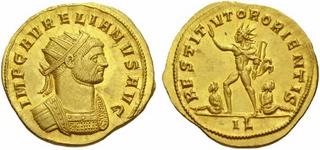

Silver drachm of Hormazd I (r. 272-273 CE).

The essential (and practically only) source about the family and court of Šābuhr I is again the ŠKZ. This document is a long rock inscription which can be divided in the following blocks (some of which have been already covered in this thread as one of the main sources to reconstruct Sasanian political history during the III century):

- Presentation of Šābuhr I, his ancestry and titles.

- A long and detailed description of his deeds and military victories against the Roman empire.

- The announcement that, as he was the one that the gods had chosen to protect, he would establish there, at Naqš-e Rostam several sacred fires (six in total, for himself, his wife and three of his sons) to honor the gods and for the well-being of their souls.

- Following this announcement, Šābuhr I establishes the deed of settlement, by which these sacred fires will be endowed with 1,000 lambs. And next, the king announces which sacrifices will be compulsory according to this deed of settlement.

- First, for the soul of Šābuhr I himself.

- Secondly comes a list of people mixing living and deceased members of Šābuhr I’s family, and then courtiers. Presumably, these were people particularly important to Šābuhr I or of whom he was particularly fond.

- Thirdly comes a brief list of people who lived “under the rule of Pābag the king”.

- Fourthly comes a long list of people who lived “under the rule of Ardaxšīr the king of kings”.

- And a very long list of people who lived “under the rule of under the rule of Šābuhr, king of kings”.

- The inscription closes itself with yet another invocation to the gods, and the signature of the scribe (“This is my handwriting, Hormazd, the scribe, son of Šērag, the scribe”).

Triumphal rock relief known as "Bishapur III" showing Šābuhr I surrounded by his army and courtiers.

The first thing that can be noticed by comparing these three lists is that Šābuhr I had four male sons who were named kings over different parts of the empire, but that they are not named in the same order in all lists, and some are even omitted in some of them. Let’s see first the first list, that of sacred fires:

And here also, by the inscription we have founded: One Fire, Khusrō-Šābuhr (“fair-famed is Šābuhr”) by name for our soul and to preserve our name; one Fire, Khusrō-Āduranāhīd by name, for the soul of our daughter Ādur-Anāhīd, queen of queens, and to preserve her name; one Fire, Khusrō-Ohrmazdardaxšīr by name, for the soul of our son Hormazd-Ardaxšīr, great king of Armenia, and to preserve his name; another one Fire, Khusrō-Šābuhr by name, for the soul of our son Šābuhr, king of Mesān, and to preserve his name; one Fire, Khusrō-Narsē by name, for the soul of our son the Aryan, the Mazdayasnian Narsē, king of India, Sakestān and Turān to the seashore, and to preserve his name.

Scholars consider that in this first list Šābuhr I named his progeny by the order of his affection towards them. First comes his daughter Ādur-Anāhīd, who was obviously not a candidate for succession; it’s interesting nevertheless that she carried the title “queen of queens”; that must imply that Šābuhr I was quite fond of her.

Among his sons, Hormazd-Ardaxšīr comes the first. He enjoys also a very special title, that of Great King of Armenia (wuzurg šāh arminān). No other sub-king in the empire, not even if they were members of the House of Sāsān, enjoyed the title of “Great King”. Scholars suppose that it was created purposefully after the annexation of Armenia in order to remark the exceptional importance that this kingdom had for the Sasanians, and that because of its exceptionality Šābuhr I would have conceived it as the title to be carried by his heir apparent. As we have seen before, Hormazd-Ardaxšīr is also the only one amongst Šābuhr I’s sons whose participation in the campaigns of his father is attested in the sources. He would succeed his father as šāhān šāh as Hormazd I.

The following one among Šābuhr I’s sons named in this first list is Šābuhr king of Mesān (mesān šāh). Little or nothing is known about him, except that according to (very dubious) Manichaean texts, he was converted by Mani to the Manichaean religion.

The last of Šābuhr I’s sons to whom a fire is dedicated is Narsē; he must’ve been something of a special case too because he’s called “the Mazdayasnian Narsē”, which must’ve been a sign that he was seen as especially pious and attached to the Mazdean tradition. He also boasted an impressive array of titles, “king of India, Sakestān and Turān to the seashore” (šāh hind sagestān ud tūrestān). Traditionally, before the conquest of Armenia the title of king of Sakestān (or “king of the Sakas”) had also been viewed as a prerogative of the heir apparent. Eventually, twenty years after his father’s death Narsē would also rise to the throne of the Sasanian empire.

Let’s look now though at the second list, which offer some puzzling revelations based on the order in which its members appear listed (scholars are quite sure that the order of precedence in inscriptions or other official documents was not something random, but that it followed a strict order dictated by social hierarchy or royal favor):

Sāsān the lord; and Pābag the king; and Šābuhr the king, son of Pābag; and Ardaxšīr, king of kings; and Xvarrānzēm, queen of the kingdom; and Ādur-Anāhīd, queen of queens; and Dēnag, the queen; and Bahrām, king of Gēlān; and Šābuhr, king of Mesān; and Hormazd- Ardaxšīr, great king of Armenia; and Narsē, king of Sakestān; and Šābuhrduxtag, queen of Sakestān; and Narsēduxt, queen of Sakestān; and Cašmag, the (royal) lady; and Pērōz, the (royal) prince; and Mirrōd, the lady, mother of king of kings Šābuhr; and Narsē, the prince; and Rōdduxt, the princess, daughter of Anōšag; and Varāzduxt, daughter of Xvarrānzēm; and Staxriyād, the queen; and Hormazdag, son of the king of Armenia, Hormazd; and Ōdābaxt, and Vahrām, and Šābuhr, and Pērōz, sons of the king of Mesene; and Šābuhrduxtag, daughter of the king of Mesene; Ohrmazdduxtag, daughter of the king of Sakestān –for their soul (each day) one lamb, one grīv and five handfuls of bread, and four pās of wine.

This list is quite longer, and the first thing to be noted is that first of all Šābuhr I notes down his ancestors in chronological order: Sāsān, Pābag, Šābuhr (eldest brother of Ardaxšīr I) and finally Ardaxšīr I. The order of precedence of the three following names, queens Xvarrānzēm, Ādur-Anāhīd and Dēnag, is unclear. From the previous list we know that Ādur-Anāhīd was his daughter, and from the list of the relatives and courtiers of Ardaxšīr I we know that a certain Dēnag had been the mother of king Pābag (and so she was Šābuhr I’s great-grandmother) and that another Dēnag, who appears also listed in the list of Ardaxšīr I’s courtiers as “queen of queens” (bānbišnān bānbišn) and as “daughter of Pābag, the king”. According to some scholars (like P.Gignoux), she must’ve been Ardaxšīr I’s sister and also his wife (but not the mother of Šābuhr I), in an example of the type of consanguineous marriage favored by the Zoroastrian tradition and priesthood (xwēdōdah), but other scholars (like A.Maricq and J.Harmatta) believe that the title of “queen of queens” reflected social rank rather than family status, and that thus it was no indications that the bearer of the title was the wife of the ruling šāhān šāh.

Thus, Dēnag as sister of Ardaxšīr I bore the title of “queen of queens” under her brother’s (and perhaps husband) rule, but later she lost it, and “dropped” in hierarchy to be listed after her grand-niece Ādur-Anāhīd, who wore the title under Šābuhr I. The same rationale and doubts applied to Dēnag stand also in Ādur-Anāhīd’s case: was she also his father’s wife? Nothing else is known about Xvarrānzēm and about the title she enjoyed (“queen of the kingdom”, šahr bānbišn).

After these three queens, we find a surprise. The first man listed is a certain Bahrām, king of Gēlān. And scholars have been able to identify this Bahrām with none other than Bahrām I, who succeeded Hormazd I as šāhān šāh in 273 CE. He’s followed by the other three kings that we already saw in the previous list: Šābuhr, king of Mesān, Hormazd- Ardaxšīr, great king of Armenia; and Narsē, king of Sakestān. Given that these three kings were Šābuhr I’s sons, it seems logical to assume that Bahrām, king of Gēlān was also a son of Šābuhr I. Scholaly consensus about the different order in this list for Šābuhr I’s sons in this second list is that in this one they appear listed by order of birth, while in the first list they were deliberately listed by Šābuhr I according to his preferences. This is further reinforced because Bahrām appears already depicted as a little child in the investiture relief of Ardaxšīr I at Naqš-e Rajab which is dated to shortly after 224 CE. Thus, by order of birth Bahrām was the first-born son, but he was clearly not his father’s favorite, to the point that Šābuhr I did not even include him in the list of people to whom sacred fires would be dedicated. Šābuhr, king of Mesān was the second-born son, Hormazd- Ardaxšīr, great king of Armenia was the third-born son and Narsē, king of Sakestān was the youngest.

Investiture relief of Ardaxšīr I at Naqš-e Rajab. Šābuhr I stands behind his father to the left of the image, while the future Bahrām, king of Gēlān is the little child in the middle, which is depicted in front of an image of Hercules/Herakles/Verethragna, which is the Iranian warrior god after whom he was named (Avestan Verethragna became Bahrām in Middle Persian).

Clearly, the order in which Šābuhr I’s sons appear listed in the first list is the order of preference which they held on their father’s eyes, and the third son Hormazd-Ardaxšīr was Šābuhr I was his favorite son. Therefore, he named him Great King of Armenia and invested him as his heir apparent, while the eldest son Bahrām was relegated into obscurity and provided only with the rather secondary title of king of Gēlān (a mountainous area in northern Iran in the Alborz mountains), which ranked clearly under the kingdoms held by his three other brothers. This decision of Šābuhr I was potentially problematic, but it seems that he was strong and respected enough as a king that it was enacted after his death, although the short reign of Hormazd-Ardaxšīr caused the problem to reappear just a year after his father’s decease.

After these four kings, the remaining royal relatives are listed in strict hierarchical order: first the wives of te kings (in the same order of precedence as their husbands) and then their sons and daughters, also following the same order of precedence as their fathers (curiously, the kings have precedence over the queens, but sons and daughters are listed together). Immediately before this listing of grandsons and granddaughters of Šābuhr I there are though some characters named that probably include siblings, cousins and other relatives of Šābuhr I which in the hierarchy of the court ranked higher than his grandchildren. Two among these characters are worth mentioning. One is “Pērōz, the (royal) prince”, who could be the same Pērōz who appears in Manichaean sources as a brother of Šābuhr I and one of Mani’s followers and protectors. The other character is “Mirrōd, the lady, mother of king of kings Šābuhr”; this is the same “Lady Myrod” that appears in later Islamic sources as the mother of Šābuhr I. She is quite down in the list’s hierarchy despite being the king’s mother, which has led scholars to believe that she was probably a concubine of Ardaxšīr I and hot a royal spouse.

Let’s look now at the third and final list of courtiers, which is much longer than the two previous lists:

Those who live under the rule of Šābuhr, king of kings: Ardaxšīr, king of Nodšēragān (Adiabene); Ardaxšīr, king of Kirmān; Dēnag, queen of Mesene, protected by Šābuhr; Hamazāsp, king of Viruz (Georgia); Valāš, royal prince, son of Pābag; Sāsān, royal prince, who was maintained by the Kadōg family; Narsē, royal prince, son of Pērōz; Narsē, royal prince, son of Šābuhr; Šābuhr, the bidaxš (N. “viceroy” or” royal lieutenant”); Pābag, the hazāruft (N. “commander of the thousand”, commander of the royal guard and most senior military officer); Pērōz the aspbed (N. “chief of cavalry”, another senior military commander); Ardaxšīr of the family Varāz; Ardaxšīr of the family Sūrēn; Narsē, lord of Andēgān; Ardaxšīr of the family Kārin; Vehnām, the framadār (N. “governor”); Frīg, Satrap of Gundīšābuhr; Srīdō, son of Šāhmust; Ardaxšīr ardašēršnōm (N. “joy of Ardaxšīr”); Pākcihr tahmšābuhr (N. “Šābuhr’s valiant one”); Ardaxšīr, satrap of Gōmān; Cašmag nēvšābuhr (N. “Šābuhr’s brave one”); Vehnām šābuhršnōm (N. “joy of Šābuhr”); Tīrmihr, chief of the fortress of Šahrgird; Zīk, master of ceremonies; Ardavān, of Dumbāvand; Gundfarr avgān razmjōy (N. “who seeks combat”) and Pābag pērōzšābuhr (N. “victorious for Šābuhr”) son of Šambīd; Vārzan, satrap of Gay; Kirdesrō, the bidaxš; Pābag, son of Visfarr; Valāš, son of Seleucus (an interesting case, obviously an Iranized Greek); Yazdbād, counselor of ladies (N. counselor to the queens); Pābag, the safsērdār (N. “swordbearer”); Narsē, satrap of Rind; Tiyānag, satrap of Ahmadān; Gulbed, the peristagbed (N the “chief of services” or majordomo of the royal household); Jōymard son of Rastag; Ardaxšīr son of Vēfarr; Abursām-Šābuhr the darīgān sārdār (N. “chief of personnel of the court”); Narsē son of Barrag; Šābuhr son of Narsē; Narsē, the grastbed (N. “chief steward”); Hormazd the dibīrbed (N. the “chief scribe; Nādūg, the zēndānīg (the “prison governor”); Pābag, the darbed (N. the “master of the gate”); Pāsfal son of Pāsfal; Abdaxš son of Dizbed; Kirdēr, the hērbed (an old acquantaince in this thread); Rastag, satrap of Veh- Ardaxšīr; Ardaxšīr son of (the?) Bidaxš; Mihrxvāst, the treasurer; Šābuhr, the governor; Aštād of the family Mihrān, the fravardag dibīr (N. the “scribe of epistles”), from Ray; Sāsān, the šābestan (N. the “ward of the harem”, an eunuch), son of Sāsān; Virōy, the vāzārbed (N. the “supervisor of markets”, head of the market inspectorate); Ardaxšīr, satrap of Nērēz; Bagdād son of Vardbed; Kirdēr Ardavān; Zurvāndād son of Bandag; Gunnār son of Sāsān; Mānzag the eunuch; Sāsān, the judge; Vardān, son of Nāšpād; Gulag, the varāzbed (N. the “chief of boars”, probably a warden of the royal hunt lands); altogether, one lamb, one grīv and five handfuls of bread, and four pās of wine.

This last list does not include any members of the royal family which had been already named in the second list. It does include though other sub-kings of the empire, some of whom we know were Šābuhr I’s brothers. This is the case of the first two kings listed, Ardaxšīr, king of Nodšēragān and Ardaxšīr, king of Kirmān. Hamazāsp, king of Viruz (ancient Iberia, modern Georgia) was not a member of the House of Sāsān, and so he’s listed in the last place among the kings. The list follows a strict order according to social hierarchy; first the šahrdārān (sub-kings), then the wispuhrān (members of the royal house without a kingly title), then the higher officials of the army and the civilian administration, then the wuzurgān (grandees), then the āzādān (lesser nobility) and then all the rest.

So, after the šahrdārān quoted above, we have the wispuhrān listed: Valāš, Sāsān, Narsē son of Pērōz and Narsē son of Šābuhr. Then the list goes on with the upper members of the political and military apparatus: Šābuhr, the bidaxš, Pābag, the hazāruft (or hazārbed) and Pērōz the aspbed. It’s highly probable that these three gentlemen were also members of the wuzurgān.

The list then continues with the wuzurgān; obviouly it doesn’t include all the wuzurgān of Iran, only those who were in the good graces of Šābuhr I; like under his father, the list includes members of the Sūrēn and Kārin clans. They are listed in this order:

- Ardaxšīr of the family Varāz.

- Ardaxšīr of the family Sūrēn.

- Narsē, lord of Andēgān.

- Ardaxšīr of the family Kārin.

An important issue with these lists is that, as you can see, they’re quite exhaustive, but neither the one for the relatives and courtiers of Ardaxšīr I nor the three lists for the relatives and courtiers of Šābuhr I name a kušān šāh. In a previous post I wrote about the conquest of the Kushan empire by Ardaxšīr I and Šābuhr I and the discovery of coins minted in Marv bearing in Bactrian language and script the name of a certain Ardašaro Košano. The problem is that, as you can see, there’s no trace of him in the ŠKZ, or of any descendant. The first certain mention of a kušān šāh in a Sasanian document is in the Paikuli inscription of Narsē, dated to ca. 293 CE. This kušān šāh could be Pērōz 1 (Note: because the imperial Sasanians and the Kushano-Sasanians used the same names, there’s a useful convention of using Roman numbers for the imperial Sasanians and Arabic numbers for Kushano-Sasanian kings), who issued coins during the late III and early IV centuries CE in Balkh, Herat and Gandhāra. It’s still unclear which was the exact family relationship between this minor Sasanian branch and the main branch in Iran.

As for the personality of Šābuhr I, little can be said about it from the surviving evidence. The Šāh-nāmah (which confuses and mixes the historical figures of Šābuhr I and Šābuhr II) gives a glittering report of this mythical Šābuhr as a mirror of human virtues to the point that it sounds quite fanciful; the main Islamic-era account by Tabarī (who at lest does not confuse both kings) offers a similar image. On the other side, most Graeco-Roman, western Syriac and Armenian sources paint him as a bloodthirsty barbarian. Both portraits are obviously little more than a caricature.

He was not exactly a pacifist or a humanitarian about that much we can be sure. His own account of his two in invasions of Roman territory proudly state that his men looted, killed and pillaged everywhere they could, and that was standard behavior for armies in the III century. Some Armenian, Syriac and Greek accounts also paint a ghastly picture of the way the vast columns of Roman captives were driven by Šābuhr I’s soldiers “like cattle” back to Ērānšāhr, which again seems like standard behavior of his times (one just needs to look at the Aurelian column in Rome to see how Roman soldiers behaved in enemy territory). But getting such vast numbers of people back alive (at least enough of them to populate several entire cities and conduct large-scale public works) means that the deportation was at least well organized and that it was not just done for cruelty’s sake.

Rock inscription of Šābuhr I at Hājjiābad in Fārs.

We can also be fairly sure that he was a boastful and prideful individual, judging by the inordinate amount of rock-reliefs and inscriptions he’s left behind. In several of them he’s shown as an accomplished fighter, and probably that’s more than simple propaganda. The Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah victory relief depicting the victory of the Sasanians at Hormozdgan shows bot Ardaxšīr I and Šābuhr I in battle garment and engaged in fight. Although it’s quite improbable that Ardaxšīr I killed the last Arsacid king Ardawān V with his own hands and that his son Šābuhr did the same with the latter’s “chief minister”, it’s quite probable that both men took part personally in battles in leading their men. Islamic sources depict Ardaxšīr I as an accomplished bowman, and as the inventor of the “Sasanian draw” that had not been used in Iran before him, and which favored a quicker delivery of arrows. Šābuhr I was also an accomplished bowman, and the fortuitous finding of an inscription at Hājjiābad in Fārs dated to the last decade of his reign offers us a glimpse that in his old age he was still an active man, capable of feats of archery:

This is my bow shot (of) the Mazda-worshipping lord Šāpūr, king of kings of the Iranians and non-Iranians, whose lineage is from the gods, the son of Mazda-worshipping lord Ardaxšīr, king of kings of the Iranians, whose lineage is from the gods, grandson of the lord, king Pābag. And when we shot this arrow it was before the sovereigns, and the princes of the blood and the grandees and the nobility. And when we placed our foot on this rock, and we shot an arrow beyond that cairn, but that place where the arrow was thrown, there where the arrow fell, it was not that if the cairn was there, it would not be visible from the outside, thus, we ordered that the cairn be set further down, whoever may have a “good hand,” let them place their foot on this rock and let them shoot an arrow towards that cairn, then, whoever throws the arrow toward that cairn, they have a “good hand”.

Obviously, we can’t judge today how far did Šābuhr I shoot that arrow, but clearly he judged the feat important enough that he had the inscription also repeated about a hundred km. northwest of the first, at Tang-e Borāq in an identical archeological context, on the rock of a grotto, and that he made clear that the feat had been achieved “before the sovereigns, and the princes of the blood and the grandees and the nobility”. It’s worth noting that no other Sasanian king has left a similar inscription boasting of an “athletic” achievement (or at least nothing similar has been found up to this date).

Šābuhr I, šāhān šāh ērān ud anērān, died at Bīšāpūr in May 272 CE and was peacefully succeeded by the heir he had designated, the Great King of Armenia Hormazd-Ardaxšīr, who became the new king of kings of Iranians and non-Iranians as Hormazd I.

Silver drachm of Hormazd I (r. 272-273 CE).

Last edited: