23.2 IRAN UNDER ŠĀBUHR I. THE SOCIETY OF ĒRĀNŠĀHR.

Quite a lot is known about the society of late antique Iran during the late century of Sasanian rule, but it’s unclear how much of this knowledge is applicable to early Sasanian Iran. By the VI century CE, Sasanian society was so hierarchically complex that in Middle Persian and early Islamic sources more than 600 different social ranks can be detected, which has caused an immense amount of confusion among scholars. By this time, the inflation of administrative, military and nobiliary titles had also reached such levels that East Roman and Islamic sources are routinely confused by them and mix titles, names and family names when referring to individuals. It’s highly unlikely that during the reigns of Ardaxšir I and Šābuhr I the situation was already so extreme in this respect, but it’s probably under them when the trend began towards an ever-increasing degree of elaboration of social hierarchies.

I’ll try to describe here in broad strokes what could have been the situation in the III century CE and which titles and ranks can be reasonably placed in this timeframe without falling in anachronisms. This is made more difficult by the fact that all the remaining sources date from the last century of Sasanian rule, or were written after the fall of the Sasanian empire. This also includes the Zoroastrian

Pahlavi Books, which are the

Dēnkard (written in the X century in Middle Persian) and the

Bundahišn, which is dated (very tentatively) in the VIII-IX centuries. The other later sources were written by Islamic authors in New Persian or Arabic during the IX-XI centuries.

The source of Iranian law under the Sasanians was the Zoroastrian tradition, which encompassed all the aspects of life (in a following post I’ll deal with the thorny issues of what was exactly understood as the “proper” Zoroastrian tradition and who got to determine it). As Ohrmazd had established order out of chaos and battled for the triumph of order in the cosmos, so the king had to battle and fight chaos in order to bring order in earth. Order made possible the well-being of the people, and order could only be ensured by the proper dispensation of justice by the king. If the king was unjust, then society would be thrown into chaos (this is a concept deeply enshrined in Iranian tradition, and which appears once and again in that epic compilation of Iranian national legends and traditions that is the

Šāh-nāmah of Ferdowsī). And if society and its order was thrown into disorder, it was incumbent to the king to bring back order in society. And by this, what was understood was an orderly class division, which the extant sources defend vehemently.

The concept of social order was synonymous in Sasanian times with that of class division. According to what can be discerned from the

Dēnkard and

Bundahišn this class division was extraordinarily rigid, but scholars are unsure if this was so in reality in Sasanian times or if this is just a theoretical abstraction put together by Zoroastrian priests that never got to be really applied in full. According to these legal principles, Sasanian society was divided into four classes (

pēšag), which were (in order of precedence):

- The priests (āsrōnān).

- The warriors (arteštārān).

- The husbandmen (wāstaryōšān) and farmers (dahigān).

- The artisans and traders (hutuxšān), which were treated by Zoroastrian law as an estate separated from the other three and as being somewhat like a class of outcasts.

In turn, each of these classes/estates were subdivided into different ranks. The priests were divided into:

- The chief priests (mowbedān).

- Priests attending the fires (hērbedān).

- Expert theologians (dastūrān).

- Judges (dādwarān).

- Learned priests (radān).

Surviving Middle Persian texts like the

Hērbedestān provide even more titles and functions, which attests to the high degree of specialization and the ubiquity of the priestly estate in all the fields of Sasanian public life. As can be seen from the above list, judges were chosen among them, because the law was based on Zoroastrian religion and custom. In a similar way to what would later happen in the Islamic world with religious minorities, non-Zoroastrians were allowed their own judges and to use their own law for internal affairs, but in criminal cases or in cases where a Zoroastrian believer was involved, the case had to be ruled by a

dādwar from among the Zoroastrian priesthood. They also acted as councilors (

andarzbed) and, according to epigraphic remains, there were also councilor-priests (

mowān andarzbed) who enjoyed the status of important functionaries. Another important priestly office quoted in extant sources was the Priest of Ohrmazd (

ohrmazd mowbed); but please keep always in mind that scholars are not sure of when each of these titles appeared (or disappeared), which were their exact functions and if said functions varied over time. By the fifth century CE each class of priests had its own chief and there’s evidence for two of them, the chief of the

mowbedān known as

mowbedān mowbed (for this post, the first attested appointee is Kirdēr in the late III century CE, according to the KKZ), and for the teacher-priests attending the fires, the

hērbedān hērbed.

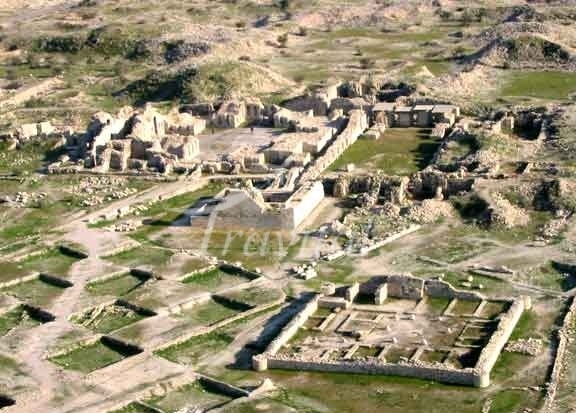

Remains of the Bahram Fire temple near Rayy, Iran.

Priests were trained in seminaries where religious scripture and prayers were learned and memorized and theological matters were discussed under supervision. These religious schools included the mowestāns and hērbedestāns. In certain sources a title also appears which seems to have been the highest position among the priests which may be translated as “Zoroaster-like” (

zarduxšttom). The

zarduxšttom’s residence is not clear but he certainly had to remain in the empire and not venture out if the surviving Middle Persian sources are to be believed.

The term which covered the religious body as a whole was

dēnbarān, “those who were concerned with learning and culture” (

frahang). The performance of correct ritual ceremonies (Sasanian Zoroastrianism was a religion which revolved around the correct performance of sacred rituals, above all the

Yasna, which included the daily recitation by the priests -by memory alone- of its 72-part text which included the

Gathas of Zoroaster) brought about the success of the warriors against the enemy and of the farmers for better cultivation of the land and salvation for the masses.

Thus, not only the priests’ guidance, but also their actions, made certain the well-being of the society. The Middle Persian text known as the

Dādestān ī Mēnōg ī Xrad (the

Book of a Thousand Judgements) spells out the functions of the priest and the activities in which a priest should not partake. These include the usual expectations from a priest of any religion:

to uphold the religion, worshipping the deities, passing judgments in religious and ritual matters based on past testaments, directing people to do well, and to show the way to heaven and to invoke the fear of hell.

Not all priests were of course working in the state apparatus or were part of the Zoroastrian state church; some were either denounced or simply seen as heretic (a process that probably began with Kirdēr). The priests not only functioned in the religious and the legal apparatus, but also in the economic sphere as well. They were in charge of overlooking the taxes which were to be collected for the state as is evidenced by the appearance of their signature in the form of signet rings on bullae or on

ostracae. In one instance a priest was condemned for cheating or lying on a question of jurisdictions between several priestly courts. The

hērbedān also functioned as teachers of the religious hymns and rituals for the people, and their religious focal points were probably the fire-temples (

ātaxš kadag) which were present in every village, town and city and whose remains can still be found today scattered across the Iranian countryside and which are known commonly as

Chahar Taq. The fire-temples were frequented not only by those who wanted to say their prayer before the sacred fire or listen to the

hērbed, but also in time of hunger and thirst people would seek the fire-temples for relief.

The estate of the warriors (

artēštārān) composed the second estate of the society and its function was to protect the empire and its subjects from external foes. This estate was formed essentially by the nobility, the supposed role of the warriors was to protect the empire, and to deal with people with gentility and keep their oath. Obviously, this was a very diverse estate, which included the sub-kings members of the House of Sāsān (

šahrdārān), members of the royal house without a kingly title (

wispuhrān), grandees (

wuzurgān), lesser nobility (

āzādān) and the gentry (

dehgān). A further subdivision which was parallel to the former one was that between cavalrymen (

asvārān) and infantrymen (

paygān). Due to the military traditions of the Iranians, cavalrymen enjoyed a much higher status than infantrymen, and the fact that the warriors had to pay for their own equipment ensured that the prestigious ranks of the

asvārān were filled with the upper classes of the nobility and their immediate retainers.

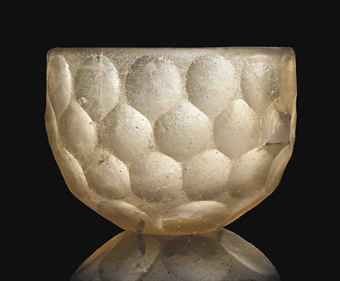

Portrait of a nobleman at the center of a golden phial bowl, dated to the III-IV centuries CE.

Just as the clergy had to attend seminaries, the soldiers were also to be trained in the military sciences and manuals of military warfare which were in existence and whose remnants are present in the

artēštārestān in the

Dēnkard. The alliance between the priests and the warriors was of paramount importance since the idea of

Ērānšāhr, which had manifested itself under the Sasanians as a set territory ruled by the warrior aristocracy, conceptually had been developed and revived by the priests. This alliance was very important in the survival of the state at the beginning of the Sasanian empire, and it became part of the idyllic axiom of the Zoroastrian religion, where religion and the state were seen as two pillars which were inseparable from each other (the reality proved to be much different from this theoretical vision, though).

All the major offices in the army (

spāh) were filled by the nobility (as under the Arsacids and as until the fall of the Sasanian empire). Although later Middle Persian and Islamic sources give very detailed list of military posts, almost none of them can be dated with any certainty to the times of Šābuhr I. The major titles which are quoted in the ŠKZ for high-ranking members of Šābuhr I’s court are (by order of precedence):

- Šābuhr, the bidaxš; this was a very high-ranking title which scholars translate roughly as “viceroy” or “king’s lieutenant”. If we take it for what it seems its literal meaning, this was a vice-king who was to act as second to the king and fulfill his role in his absence.

- Pābag, the hazāruft (or hazārbēd); literally “the commander of the thousand”. Scholars believe that he was originally the commander of the royal guard, and by extension of the whole royal “private” army as well.

- Pērōz, the aspbēd (chief of cavalry); it was an office inherited from Arsacid times (when the aspbēd had been the second in command of the army after the king).

These are the only army command posts that can be securely dated to the reign of Šābuhr I. A new development in the Sasanian army under Šābuhr I was the appearance of a corps of war elephants (

pīl-bānān), which would remain an important element of the

spāh until the Muslim conquest. The Islamic author Tabarī wrote that Šābuhr I used these animals to raze the city of Hatra after conquering it. Most probably, the addition of elephants to the Sasanian army (the Arsacids had never used them) was a result of Šābuhr I’s conquests in the East against the Kushans. For the reign of Šābuhr I a sophisticated approach to siege warfare is also attested by the spectacular finds at Dura Europos, where it became clear that the Sasanian army had become equal to the Roman one in this field, with the use of mines, ramps and even poisonous gas. According to the IV century CE author Ammianus Marcellinus, the only field where the Romans retained a technical advantage was in artillery.

Sasanian royalty, nobles, priests and scribes used personal ring seals . This drawing by the Belgian numismatist Ryka Gyselen depicts the personal seal of Weh-dēn-Šābuhr Ērānanbaragbed, a member of the nobility and a high functionary (the Ērānanbaragbed was in command of the overall supply of the whole Sasanian military).

The third estate consisted of the husbandmen (

wāstaryōšān), and farmers (

dahigān), whose function was to till the land and keep the empire prosperous, and were represented by a chief of husbandmen (

wāstaryōšān sālār). They were producers of the foodstuffs as well as the tax base for the empire and as a result the land under cultivation was surveyed by the government and taxes exacted from it, although probably this was only true for the lands under direct royal control. Land cultivation was a pious act according to the Zoroastrian religion and letting it sit idle a sin. The function of the farmers was “farming and bringing cultivation and as much as possible, bringing ease and prosperity.”

The fourth estate was treated somewhat separately by Zoroastrian law. They were the traders and artisans (

hutuxšān). Based on the structure and the differentiating language in extant Middle Persian texts, an uneasiness by the priests towards the artisans/merchants can be perceived. In chapter 30 of the

Dādestān ī Mēnōg ī Xrad, the author discusses the function of the first three estates, and while the priests, warriors, and husbandmen/peasants are treated under this chapter the artisans are treated in a separate section in chapter 31. The language and the length employed in specifying the function of this estate reflects the negative view of the Zoroastrian priesthood regarding the artisan class:

(They) should not undertake a task with which they are not familiar, and perform well and with concentration those tasks which they know. Ask for fair wages, because if someone does not know a task and performs that task, it is possible for him to ruin it or leave it unfinished, and that man himself is satisfied it would be a sin for him.

The negative tone of this passage when compared with that of the previous chapter dealing with the first three estates shows that when Zoroastrian priests began to codify laws in regard to social matters, the artisans/merchants were placed at the very bottom. This dim view of the artisans or the merchant class is especially important in the face of the large number of artisans/merchants in the Sasanian empire in Late Antiquity. This negative view probably contributed to the reduction of the involvement of Zoroastrian believers in these tasks which were left to religious minorities. It also appears that the government was never involved in opening economic markets or actively engaged in business, but rather private individuals were to be the major proponents of trade. The government was only to assure the upkeep and safety of the roads and to exact toll road taxes.

This also reflects a deep incongruence (almost a “schizophrenic” attitude) on behalf of Sasanian kings. On one side, they were deeply tied to Zoroastrianism, its core beliefs and its priesthood and traditions (which we should remember were also those of the very class they represented and which ruled the empire, the Iranian nobility). They took pains in showing themselves as stout supporters of the Good Religion: in his rock inscriptions, Šābuhr I called himself “the Mazdayasnian (or Mazda-whorshipping) Majesty”, boasted about his foundation of many sacred fires and his protection of the Zoroastrian priesthood and in the reverse of his coins a fire altar is always shown. But on the other hand he built a large number of new towns and cities which were centers of trade and artisan activity, and filled them with non-Zoroastrian deportees. As we will see in a later post, Šābuhr I is a somewhat special case, but all his successors including those who were much more unwavering supporters of Zoroastrianism (like Šābuhr II) kept exactly the same politics in this respect, which has led to perplexity among historians. Because what is true is that in the long run the proliferation of new cities and the growing urbanization of the Iranian plateau contributed to the undermining of the archaic social order which was based in the old Iranian pre-Iron Age traditions of which Zoroastrianism was their religious reflection. Already under Šābuhr I, this tension began to surface with the king’s protection of Mani, which probably raised great outrage among the ranks of the

āsrōnān.

The ranks of the merchants and artisans in the older cities (like Ctesiphon or Susa) and in the new ones, either outside or inside the Iranian plateau, were filled by Jews, Christians, Manicheans, Mandaeans, Buddhists and several other assorted minorities, whose members were usually also not ethnical Iranians, but rather Semitic Arameans or Arabs in the west and Sogdians in the east, and this in turn only served to entrench more the mistrust of the Zoroastrian priesthood over them. This may be a reason why Islam spread rapidly when it was introduced to the Iranian plateau, because it was business-friendly. After all the Prophet Muhammad, a merchant himself, lived in Mecca, an important trading city, and he was well aware of the importance of the merchant class in society.

Royal workshops were controlled by the state to hold up the standards in the making of such commodities as the silver dishes used as propaganda instruments and the production of glass and other goods for the nobility. Roman and Mesopotamian skilled workers were among this group which used Roman techniques in artistic production. The cities where these foreign laborers were established and those who worked in the royal workshops (probably under the status of royal slaves captured in war) were kept under close watch. A guild Master (

Kārragbed) was in charge of the production and the workers. All four estates were overseen by a

pēšag sālār which according to legal texts was the chief of the estates and ensured the maintenance of the proper social order.

Of course, this division was what is reflected in Zoroastrian religious and legal texts which as I’ve said before are dated in some cases to three centuries after the fall of the Sasanian empire. If we were to believe them, a poor Zoroastrian peasant would be privileged by law with respect to, let’s say a rich Christian Aramean merchant ... which sounds quite improbable.

As the complexity of the Sasanian state grew, the number of professional bureaucrats grew accordingly. Although they never formed an estate according to the archaic class system of Zoroastrian law, bureaucrats belonged to an “informal” social class of scribes (

dibīrān). It’s perhaps symptomatic of the deep conservatism of Iranian society that it still needed a class os scribes when professional scribes had all but disappeared from other settled cultures both to the east and west of the Iranian plateau. This was due to the archaic writing system that was employed in Arsacid and Sasanian times: the Pahlavi scripts which were used to write the Parthian and Middle Persian languages.

The Pahlavi script is first attested in coins issued by king Aršak I, the founder of the Arsacid dynasty. The word for “Parthian” in the Parthian language is “Pahlavi”, and hence the name with which these scripts are known. It’s a script derived from the imperial Aramaic script which was a modification of the Aramaic alphabet used under the Achaemenids to write down the several Iranian languages (of which the best attested under the Achaemenids is Old Persian). The main types of Pahlavi scripts are:

- Inscriptional Parthian, used by the arsacid kings in their monumental inscriptions.

- Inscriptional Pahlavi, used by the Sasanian kings in their great rock inscriptions like the ŠKZ.

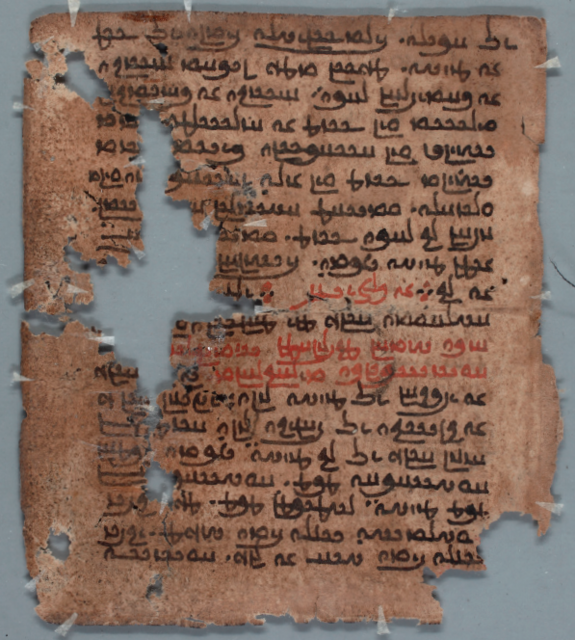

- Psalter Pahlavi, whose name is derived from the so-called "Pahlavi Psalter", a VI-VII century CE translation of a Syriac book of psalms; its use was peculiar to the Nestorian Church of the East which flourished across the Sasanian empire under Sasanian rule.

- Book Pahlavi, which was the most common form of the script and the one which is better known, as all the surviving Zoroastrian religious literature that has survived in Middle Persian was written using this script, which was kept in use by the Zoroastrian clergy well after the Islamization of the Iranian plateau.

It’s a common mistake to refer to the language spoken by the Sasanian kings which became the official language of the Sasanian empire as “Pahlavi”. The correct name for the language is Middle Persian (

Pārsīg), the use of the term “Pahlavi” to refer to it was a development of the early medieval era, when “Pahlavi” became the term to refer to the older form of Persian to which the remaining Zoroastrians still clung to, in opposition to the new language “Farsi” (known in linguistics as New Persian). The most distinctive trait of Pahlavi scripts is that, although they were originally based on an alphabetical writing system, they were not alphabetical scripts.

A folio of the Pahlavi Psalter.

The most puzzling characteristic of Pahlavi scripts was the use of logograms (known as

huzvārishn in Middle Persian): many common words, including even pronouns, particles, numerals, and auxiliaries, were spelled according to their Aramaic equivalents, but were to be read as Iranian words, which sounded completely different to their Aramaic counterparts. For example, the word for "dog" was written as ⟨

KLBʼ⟩ (Aramaic

kalbā) but pronounced

sag (the Persian word for “dog”); and the word for "bread" would be written as Aramaic ⟨

LḤMʼ⟩ (

laḥmā) but understood as the sign for Persian

nān (notice also how, following the custom of Semitic alphabets, the system included no vowels). And the “fun” did not end here: a logogram could also be followed by letters expressing parts of the Persian word phonetically, for example ⟨

ʼB-tr⟩ for

pitar "father". Grammatical endings were usually also written phonetically (but as in Persian, not as in Aramaic). A logogram did not necessarily originate from the lexical form of the word in Aramaic, it could also come from a declined or conjugated Aramaic form. For example,

tō "you" (singular) was spelt ⟨

LK⟩ (Aramaic "to you", including the preposition

l-). A word could be written phonetically even when a logogram for it existed (

pitar could be ⟨

ʼB-tr⟩ or ⟨

pytr⟩), but logograms were nevertheless used very frequently in texts.

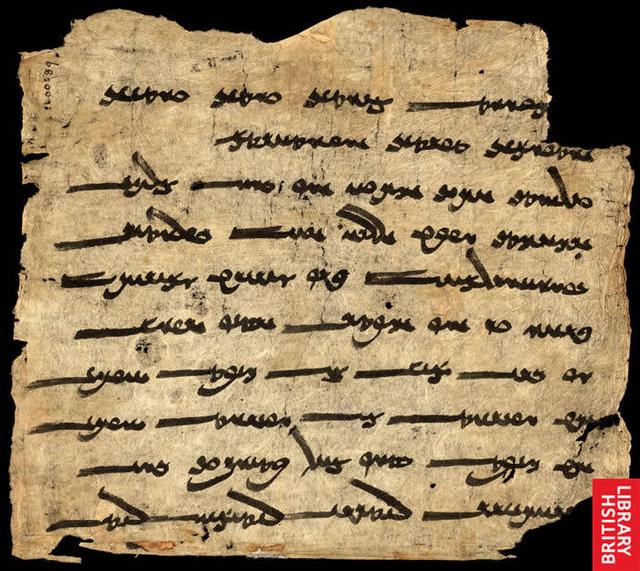

This is the oldest surviving manuscript of a sacred Zoroastrian text. containing the Ashem Vohu, a part of the Yasna. It's dated to the X century and it was found in Dunhuang in Xinjiang, it's written in the Sogdian language using the Avestan script.

The convergence in form of many of the characters of Book Pahlavi causes a high degree of ambiguity in most Pahlavi writing which can only be solved by the context. Some mergers are restricted to particular groups of words or individual spellings. Further ambiguity is added by the fact that even outside of ligatures, the boundaries between letters are not clear, and many letters look identical to combinations of other letters. As an example, one may take the fact that the name of God,

Ohrmazd, could equally be read (and, in

Pārs, often was read)

Anhoma. The system was so open to confusion that when the priests finally decided to write the Avesta down, they developed a specifically unambiguous fully alphabetical system for it, the Avestan alphabet. The insistence of the peoples of the Iranian plateau in keeping this cumbersome and complex script is puzzling considering that their eastern and western neighbors, as well as some communities within the empire used alphabetic scripts: Sogdian and Bactrian (both Iranian languages), Sanskrit, Aramaic (main language in Mesopotamia and Khuzestan), Arabic, Armenian, Greek and Latin all used alphabetical scripts.

The complexity of Book Pahlavi and the great number of languages that were spoken within the vast Sasanian empire made scribes indispensable for Sasanian kings. They performed a variety of functions and needed to have several skills. Some scribes accompanied the Sasanian army and were in its service (

dibīr-spāh and

gund-dibīr) while other scribes were in the employment of the local provincial kings. Royal scribes were also responsible for ordering the writing of the imperial inscriptions, and then written drafts were translated into Greek, Arabic, Sanskrit and other languages. Some had to be bilingual for translating and writing in other languages and probably some were drawn from Rome, Arabia and other regions. The scribes have left us seals which demonstrate their rank and the region they covered, from simple

dibīr to the chief scribe (

dibīrbed). At schools (

dibīrstān), the

dibīrān were expected to be able to learn different forms of handwriting, such as calligraphic script (

xūb-nibēg), shorthand script (

rag-nibēg), subtle knowledge (

bārīk-dānišn), and to develop nimble fingers (

kāmgār-angust). Apparently they were expected to have knowledge of different scripts employed for writing which included the religious script (

dēn-dibīrīh), that is., the Avestan script which was invented in the Sasanian period (which was not a Pahlavi script) and a “comprehensive script” (

wīš-dibīrīh) whose nature and function is unclear. Islamic sources state that it was used for physiognomy, divination and other "unorthodox" purposes. A third script, known as turned or cursive script (

gaštag-dibīrīh) was used for recording contracts and other legal documents, medicine and philosophy; and there even existed a “secret script” (

rāz-dibīrīh) was for such affairs as secret correspondence among kings. A sixth script was used for letters (

nāmag-dibīrīh), and the seventh was the common script (

hām-dibīrīh). The

dibīrān were to draft letters (

nāmag) and correspondence (

frawardag) and a specimen of a manual of style about the manner in which one should write for different purposes and occasions has survived to our days.

The ranks of the

dibīrān included also the accountants (

āmār-dibīrān) who used a specific script known as

šahr-āmār-dibīrīh. The court accountant (

kadag-āmār-dibīr) used the

kadag-āmār-dibīrīh, the treasury accountants (

ganj-āmār-dibīrān) used the

ganj-āmār-dibīrīh script, and the accountant of the royal stables (

āxwar-āmār-dibīr) used the (

āxwar-āmār-dibīrīh) script. There were also accountants employed by the fire-temples, (

ātaxšān-āmār-dibīrān) who used the

ātaxšān-āmār-dibīrīh script. The accountants of the pious foundations (

ruwānagān-āmār-dibīrān) used the

ruwānagān-dibīrīh script. Royal tax collectors sent to the provinces of the empire were known as

šahr-dibīr. Judicial decisions were written down by legal scribes (

dād-dibīrān) who used the

dād-dibīrīh script. Documents or contracts drawn up by these scribes in relation to legal matters were taken from a known legal phraseology and then signed with wax and seal (

gil ud nāmag), and copies were kept in separate archives (

nāmag-miyān). They also had to keep a record of the minutes in tribunals of inquiry. These legal scribes were probably drawn from the clergy as they had to deal with Zoroastrian law. There were several kinds of contracts and documents which included royal decrees (

dibīpādixšāykard), treaties (

pādixšīr), certificates of divorce (

hilišn-nāmag), manumission certificates (

āzād-nāmag), and title deeds for the transfer of property for pious purposes (

pādixšīr), ordeal warrants (

uzdād-nāmag) as well as an ordeal document (

yazišn-nāmag) drawn up for the guilty. In relation to the holy scripture, the copiers of the scripture (

dēn-dibīrān) used the

dēn-dibīrīh to write down sacred texts (including the Avesta). The head of the scribes like any other profession held the title with the suffix “master” (

-bed), thus

dibīrbed. The scribes had an increasingly important presence in the Sasanian court across its 400-year history and with the coming of the Arabs, they were to stay and render their services to the Caliphate.

What one can surmise from this overly complicated (and probably incomplete) list (which I’ve extracted from Touraj Daryaee’s book

Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire) is that although Sasanian society was highly bureaucratized and made ample use of written texts, the writing system of Middle Persian was, by its very nature, reserved for the use of a handful of professional scribes who only complicated matters further by multiplying the variants of script in use. Still today scholars have troubles trying to read many Pahlavi texts, and the rendition of Middle Persian words into Latin script is notably inconsistent (Shapur, Shapuhr, Šābuhr, Šāpuhr, etc.) mainly because scholars can’t agree about the exact reading and pronunciation of many words. The result of this was that literacy only became relatively commonplace among merchants and artisans in the cities but not in Pahlavi script, but in Aramaic, Sogdian, Manichean, and other alphabetic scripts that were much easier to master.