The Rise of the Sasanians

- Thread starter Semper Victor

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Threadmarks

View all 68 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

22. THE AFTERMATH OF EDESSA. ŠĀBUHR I’S SECOND ONSLAUGHT AGAINST THE ROMAN EAST. 20.3. ŠĀBUHR I’S SECOND CAMPAIGN. THE BATTLE OF BARBALISSOS. 20.4. ŠĀBUHR I’S SECOND CAMPAIGN. THE RAVAGING OF SYRIA AND THE FIRST CAPTURE OF ANTIOCH. 21.1. VALERIAN´S REIGN. THE PROMISING BEGINNINGS. 21.2. ŠĀBUHR I’S RETREAT. 24.6 THE REORGANIZATION OF THE ROMAN DEFENSES IN THE EAST BY DIOCLETIAN. 24.7 THE REIGN OF NARSĒ AND THE ROAD TO WAR. 24.8 THE WAR BETWEEN NARSĒ AND DIOCLETIAN AND THE FIRST PEACE TREATY OF NISIBIS.I propose going until the final peace treaty in 1453. I also propose you drop everything else so we could get more frequent updates!

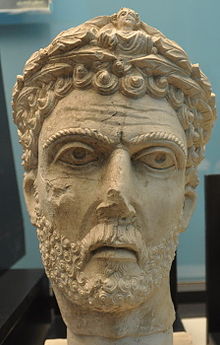

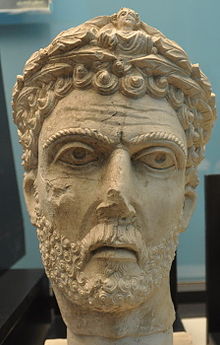

Thank you for writing, I've loved every part of this series. The focus has been on internal Roman troubles for quite a while now, which helps understanding why the Persians could get so far in their wars, but it has distracted you from the original topic a bit. I'm actually more curious about the Sassanians, of whom I know relatively little, and most of that from general histories of Persia/Iran. If you restricted yourself to focus more on the Persians, would you be able and willing to continue a bit further than Shabuhr I?Thank you for your kind words. Yes, Gallienus is a very interesting figure but I'm not sure if I’m going to write about his reign with the same depth that I've done with other Roman emperors. After all, this thread is (or it was supposed to be) centered on the first Sasanian kings, and how they became such a formidable enemy for Rome and how they contributed to the troubled times that Rome experienced during the III century CE. Gallienus’activities were restricted almost exclusively to the European parts of the empire (excluding Postumus’ Gallic empire), and as far as I'm aware the further east he ever travelled after his rise to the purple was the city of Byzantium; he never even stepped on Asian soil. My original intention was to stop the thread with the death of Shabuhr I in 273 CE, but we'll see. Another possibility would be to continue until the 298 CE peace treaty between Narseh and Diocletian, but I'm still not sure.

Thank you for writing, I've loved every part of this series. The focus has been on internal Roman troubles for quite a while now, which helps understanding why the Persians could get so far in their wars, but it has distracted you from the original topic a bit. I'm actually more curious about the Sassanians, of whom I know relatively little, and most of that from general histories of Persia/Iran. If you restricted yourself to focus more on the Persians, would you be able and willing to continue a bit further than Shabuhr I?

I'm glad that you've enjoyed it so far. Actually continuing past Shabuhr I would be not too complicated, except for the matter of finding available time. The period I'm covering right now (the 260-270 CE time frame) is the "darkest" part of the III century because of the scarcity of sources, which has made researching it somewhat of a challenge. After 270 CE, and especially for the IV century CE, written sources become again reasonably plentiful, and so writing about historical events becomes easier. For the wars between Shabuhr II and Constantius II and Julian we even have the rare luxury of having the work of a man who took part personally in most of the conflict, like Ammianus Marcellinus and having it preserved in its integrity.

Last edited:

I have immensely enjoyed your description of both 'sides' (Persian and Roman), especially since I know relatively little of both the Sasanians and later Roman Empire. However, if you do have to make a choice, I'd be in favour of focusing more on the Sasanians.

Whichever path you take, know that this is probably my favourite thread of all time, and something that continually brings me back to this forum.

Whichever path you take, know that this is probably my favourite thread of all time, and something that continually brings me back to this forum.

Whichever path you take, know that this is probably my favourite thread of all time, and something that continually brings me back to this forum.

This

Always a pleasure to pop in for a new update!

I have immensely enjoyed your description of both 'sides' (Persian and Roman), especially since I know relatively little of both the Sasanians and later Roman Empire. However, if you do have to make a choice, I'd be in favour of focusing more on the Sasanians.

Whichever path you take, know that this is probably my favourite thread of all time, and something that continually brings me back to this forum.

Thank you again. I think that I’ll finally let this thread continue until the 298 CE peace treaty between Diocletian and Narseh, and then perhaps I'll open a new thread dealing with the IV century CE I don't like threads that become too long as they become unreadable, and besides past that date it wouldn't be correct to refer to the "rise”of the Sasanians.

21.3. VALERIAN’S REIGN. THE APPEARANCE OF CONSOLIDATION AND THE ILLUSION OF STABILITY.

21.3. VALERIAN’S REIGN. THE APPEARANCE OF CONSOLIDATION AND THE ILLUSION OF STABILITY.

While Valerian was busy in the East trying to restore the shattered eastern defenses of Rome in the middle 250s CE, the Goths and their Borani allies began a new series of devastating sea raids against Rome’s Anatolian provinces. As I wrote in a previous post, they obtained the means to do so by their conquest of the Bosporan kingdom in the Crimea, which provided them with a large fleet manned by experienced sailors. Incredible as it could sound, Rome had no naval presence in the Black Sea (except for a very small squadron of light warships based at Byzantium), because until them it had been the navy of their vassal the Kingdom of Bosporus who had protected the Roman shores in this area. This would have disastrous consequences, because the Gothic naval raids would be able to even cross the straits of the Bosporus and Hellespont and enter the Aegean and the Mediterranean as far as the shores of Caria and Lycia. The Roman navy showed an extraordinary lack of ability to react to these raids, which can only be attributed to a conscious decision (or lack of reaction) by the ruling augusti to do nothing in this respect.

The deployment of the Roman fleet had not changed since the time of Augustus except in some minor details. More than half of it (perhaps as much as three quarters of its seaworthy ships) were concentrated in Italy, in the two praetorian fleets at Ravenna and Misenum. These two fleets were commanded by two equestrian officers with the rank of praefecti, who were appointed directly by the emperor. Apart from these two large fleets, the Romans had smaller squadrons at Alexandria, Carthage, Byzantium, the English Channel and perhaps another based at Cyrenaica or Tripolitania (although the existence of this squadron is a matter of debate). And then there were the two river flotillas of the Rhine and Danube. This deployment was obviously designed with two main goals in mind:

According to Zosimus, in 255 CE a force of Borani landed near the city of Pityus in Colchis (in the southwestern Caucasus coastline, in present-day Georgia, then part of the Roman province of Pontus). They attacked the city, which was then successfully defended by its small garrison under the leadership of its commander Successianus. Again according to Zosimus, upon hearing of this success, Valerian recalled Successianus to Samosata and appointed him as his Praetorian Prefect; Successianus would serve loyally as Valerian’s praefectus praetorio until the end.

But this decision by Valerian had its consequences: again according to Zosimus, the following year the Borani attacked Pityus again and this time they took the city and looted it. This defeat seems to have demoralized the Roman troops in the province of Pontus; assuming that there were many troops in the province to begin with, because usually in ”interior” provinces the Romans kept very small military forces (mostly to act in police duties). According to Zosimus, the fleet of the Borani then sailed westwards along the coast of Pontus until they reached the large city of Trebizond. Again according to Zosimus, the city was walled and had a substantial garrison, but when the Borani launched a surprise night attack against the walls the garrison panicked and fled, and the Borani captured and looted the city.

Valerian seems to have done nothing to defend the population in Pontus, probably because Šābuhr I had launched a new wave of attacks against the Roman eastern border; in 256 CE with mixed results. The Sasanians besieged Circesium without success and besieged and took once again Dura Europos (which they razed to the ground after a dramatic siege, the town became an uninhabited ruin and its dwellers were deported into Ērānšahr, to be settled as colonists in royal lands or to be sold as slaves).

The main attack though seems to have taken place in the traditional scenario of Roman-Sasanian conflicts in northern Mesopotamia, where according to Udo Hartmann and Andreas Goltz Valerian could have won a victory against the army of Šābuhr I; they speculate that perhaps the Sasanian king attacked once again the Roman-held cities of Carrhae and Edessa and Valerian reacted by massing his army and counterattacking with success. Their main proof for such assertion is that the following year the Roman mint of Antiochia issued coins with the legend VICTORIA PART(hica), and that local coins of Alexandria also boasted the Greek legend Nike (Victory). Obviously, this was far more important than defending some cities in northern Asia Minor and Valerian did not hesitate in abandoning their unlucky inhabitants to their fate.

Antoninianus of Valerian; on the reverse, RESTITVTOR ORIENTIS.

This victory seems to have given Valerian enough confidence that he’d finally secured the situation in the East that in the second half of 256 CE he left the East and returned to the West to meet with his son and grandsons and reinforce the image of unity of the imperial collegium (and his own position as senior augustus). Again this would not have been possible if he had not achieved some kind of success that allowed him to feel reasonably confident about leaving things secure in his absence, this reinforces Hartmann and Goltz’s hypothesis. His arrival into the West can be dated securely by an imperial rescript preserved in the Code of Justinian issued by Valerian and dated in the city of Rome on 10 October 256 CE. From Rome he then went to Gaul, where an epigraphic inscription attests to his presence in Colonia Ara Agrippinensis (Cologne) in August 257 CE.

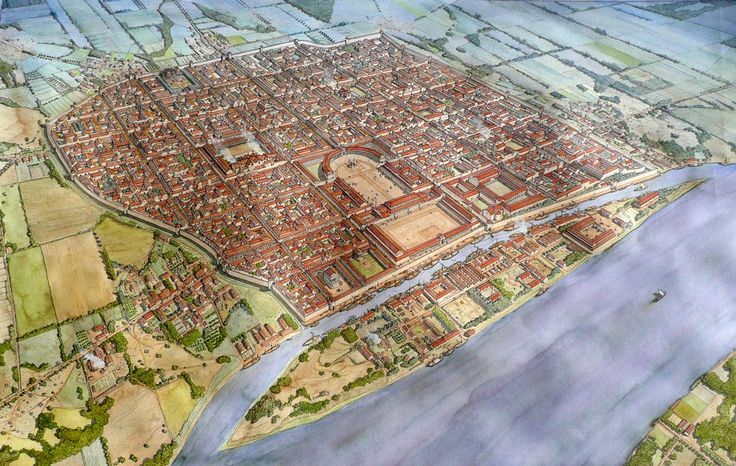

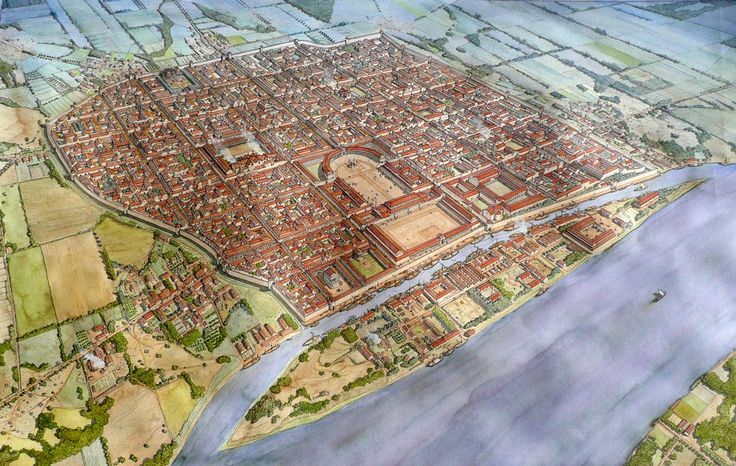

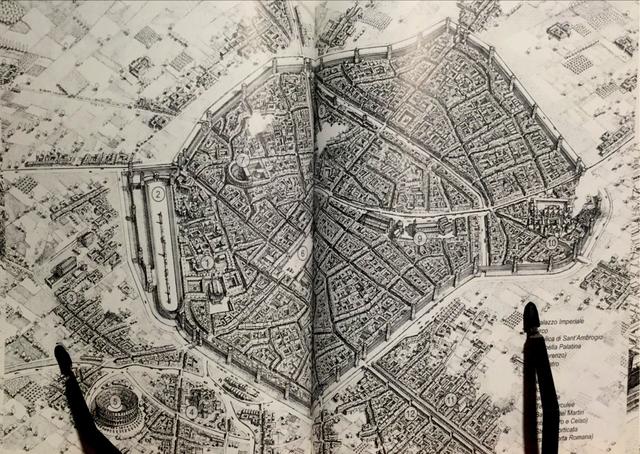

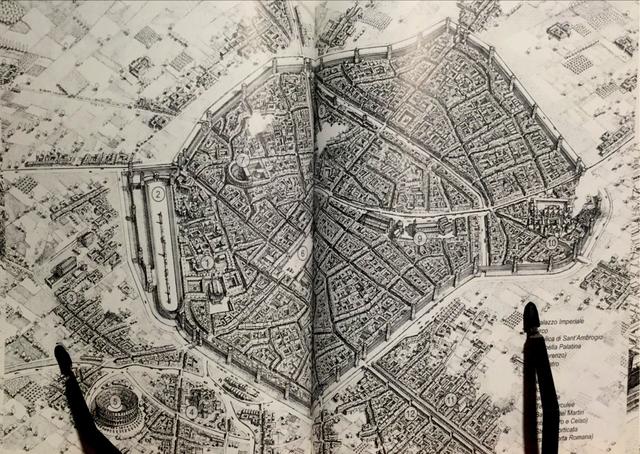

Restitution of Colonia Ara Agrippinensis by the Freanch architect and archaeologist Jean-Claude Golvin.

While his father was in the East, Gallienus had not had en easy time in the West. On departing to the East, Valerian had taken with him large numbers of troops from the European armies, especially from the two Germanias and Raetia, weakening critically the defenses in this area, which included one of the weakest stretches of border in the West, the limes germanicus that ran from near Bonna (modern Bonn in Lower Germany) to near Castra Regina (modern Regensburg) in Raetia. But between 254 and 256/257 CE, his attention seems to have been concentrated on the middle Danubian border; there are very few coins minted in the two Germanias and Raetia but there’s a large number of issues from the mint at Viminacium in Upper Moesia. Apparently his operations there were successful, because already in 254 CE he issued coins with the legend VICTORIA GERM(anica), followed in the following months and years by the legends VICTORIAE, GERMANICUS MAX (imus) and VICTORIA II GERM (anica). Probably the “Germans”against whom Gallienus fought were the Marcomanni, and it’s in this context that Hartmann and Goltz locate the notice given by Aurelius Victor that Gallienus allowed the defeated Marcomanni to settle in Roman soil and took as concubine one of the daughters of their king. Aurelius Victor wrote about this ceremony in an outraged way, and this is just one of the many sources that show open hostility to Gallienus, both Greek and Latin ones; although the Latin senatorial tradition was to remain implacably hostile to the memory of Gallienus until the end.

Antoninianus of Gallienus; on the reverse VICTORIA GERMANICA.

After these successes Gallienus returned to Rome and his presence in this city is attested in September 257 CE, probably to wait for his father’s arrival. The reason for their meeting in the capital was that they wanted to celebrate a double triumph (Valerian’s successes in the East, and Gallienus’in the Danube) and take advantage of the festive and triumphal mood to further secure the future of the Licinian dynasty by raising Valerian the Younger to the rank of caesar. Still in Rome, on 1st January 257 CE, Valerian and Gallienus again took the joint consulship (Valerian’s third, Gallienus’ second) and the mint of Rome issued a series of coins with triumphalist legends like VIRTVS AVGG, VICTORIA PART (hica), VICTORIA GERMANICA, RESTITVTOR ORBIS and FELICITAS AVGG, as well as broadcasting the image of the new caesar.

It was at this time, when the fortunes of the Licinian dynasty appeared brighter than ever, that the two augusti took a controversial decision. Scholars have discussed the issue for decades, but I tend to agree with Hartmann and Goltz that this decision was probably Valerian’s and that Gallienus mainly followed in order to preserve the image of familiar harmony and not rock the boat that they had fought so hard to keep afloat. They issued a decree that was basically a renewal of Decius’ decree on sacrifices and which although it was not specifically targeted against the Christians turned them into its main victims. According to the Acts of the Martyrs, the first effects took place in the summer of 257 CE, so the decree was probably issued at Rome in spring while the two augusti were still residing there.

The summer of 257 CE saw also a renewal in the activities of the imperial family in the borders. Valerian the Younger was sent to the Danube (now that it had been apparently “pacified” by his father) with an encompassing command for the two Pannonias, the two Moesias and Dacia. As he was barely a teenager, his father and grandfather assigned him as a tutor (who was also probably to act as the real commander in the field) an experienced general named Ingenuus about whom practically nothing is known. Meanwhile, both augusti moved to Gaul and settled in Cologne in order to stabilize the situation in the Rhenish border where things had become critical.

The degree of seriousness of the situation can be judged by two means: archaeological evidence and written sources. Archaeology shows that by this time the long limes germanicus, which had been under growing pressure since the time of Severus Alexander finally broke down and most of its forts and watchtowers were destroyed; the Agri Decumates were flooded by the Alamanni and the Roman military presence west and north of the Rhine and Danube practically ceased to exist. The Alamanni were by now known adversaries of the Romans, but they were joined further north by yet another new confederation of Germanic peoples (the Franci, or Franks) in what was yet another disastrous geopolitical development for Rome.

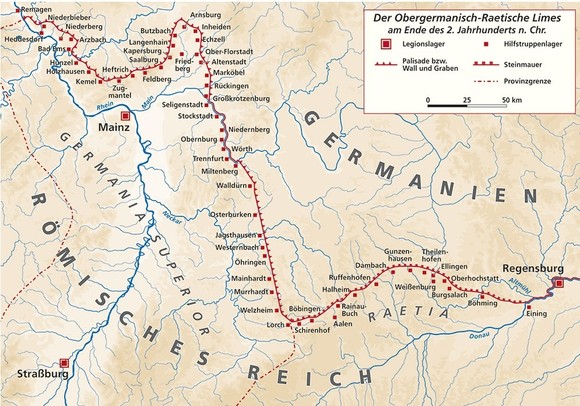

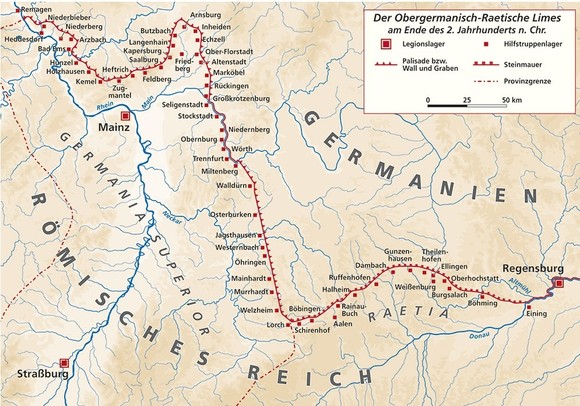

Map of the limes in Upper Germany and Raetia by the end of the II century CE.

According to the IV century CE author Aurelius Victor the Franks crossed the lower Rhine in such numbers that the weakened Roman border garrisons were unable to stop them, and they raided deep and far into Gaul, even crossing the Pyrenées and reaching Hispania. The two augusti reacted by moving immediately into Gaul, where Gallienus apparently obtained some victories, and some coins were quickly issued with the legends GERMANICVS MAX(imus) V and RESTITVTOR GALLIARVM. But to which degree these were really decisive victories is another matter. Archaeological evidence confirms widespread destruction in Germania Superior and Germania Inferior, but further to the west and south the evidence is much more scattered and isolated; rather than layers of destruction what archaeology reveals for many cities in Gaul and Hispania at this time is a widespread and sudden fever for building new city walls, usually at top speed using whatever material were at hand: tombstones, and masonry from funerary monuments and even public buildings. What’s unsure is if this was a reaction to each city suffering a Frankish or Alamannic raid or simply the result of mass hysteria. Aurelius Victor wrote that Tarraco was sacked, but archaeological digs in the modern city show no signs of destruction by this time, but this did not stop nearby Barcino (modern Barcelona) from building a city wall that was totally out of proportion with the importance and size of the city: the pomerium of the town of Barcino had perhaps 1,000 inhabitants, but the wall that was built was the second tallest and strongest in the West after the Aurelian walls of Rome itself.

But things were going to get much worse. By the spring of 258 CE Gallienus was still in Gaul and issuing again a new series of coins with the legend VICT(oria) GERMANICA which scholars are unsure if they can be taken at face value. But at this time devastating news reached him: his son Valerian the Younger (his presumptive heir) had died of natural causes in the Danube. This left the Danube under the overall command of Ingenuus without an imperial presence (always a risky situation) and Gallienus reacted by raising his second son Saloninus to the rank of caesar, although as he was still very young he did not send the boy to the Danube and instead retained him in Gaul at his side.

While the situation in the West worsened by moments, Valerian returned to East, during the end of 257 CE or the start of 258 CE. Again, an imperial rescript preserved in the Code of Justinian attests to his presence in Antiochia in May 258 CE. Despite the worsening situation and the multiplication of foreign threats, Valerian did not abandon his religious policies, and in 258 CE (when he was probably already in the East) he issued a new edict, this time specifically targeted against Christians, who had showed themselves to be the most problematic ones with respect to the previous edict. This second edict targeted directly the hierarchies of the Christian Church (bishops, deacons and presbyters) and explicitly ordained death penalties in the case of refusal to sacrifice; Cyprian of Carthage was one amongst the many victims of this second edict. An interesting point in this edict is that it also ordered harsh punishments against Christian senators and members of the domus caesari (servants of the imperial household) which is a hint at the degree of expansion that the Christian religion had attained even at the top echelons of Roman society.

This time the reason for Valerian’s return to the East doesn’t seem to have been just another wave of Sasanian attacks, but also the increasing scale and severity of Gothic sea raids. According to Zosimus, after seeing the rich booty obtained by their Borani allies, the Goths decided to follow their example and set to the sea in Bosporan ships but with much larger forces. Most alarmingly, the large Gothic fleet managed to cross the Bosporus and land its troops in the Bythinian coast of the sea of Marmara. This Gothic army then proceeded to systematically pillage, burn and destroy all the large and rich cities of Bythinia: Chalcedon, Nicomedia, Nicaea, Kios and Prusa while Cyzicus was spared because torrential rains had turned the Rhyndakos river into barrier that the Goths could not cross. Most alarmingly, and again according to Zosimus (following the lost account of Chrysogonos of Nicomedia) the Goths found ample help by disaffected elements of the civilian population, which eased their task of finding easy goals and weak spots in the defenses.

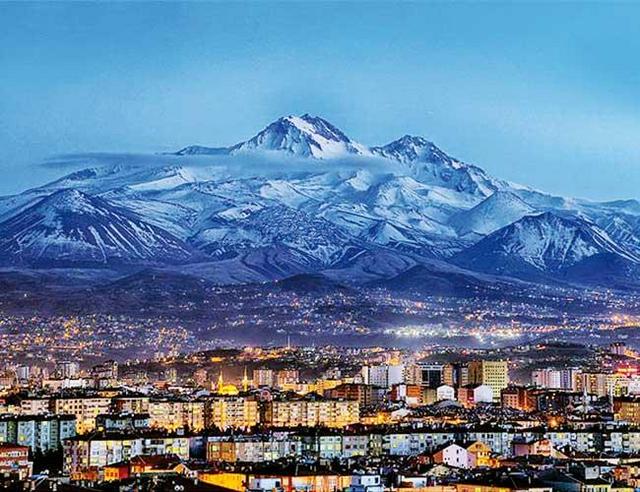

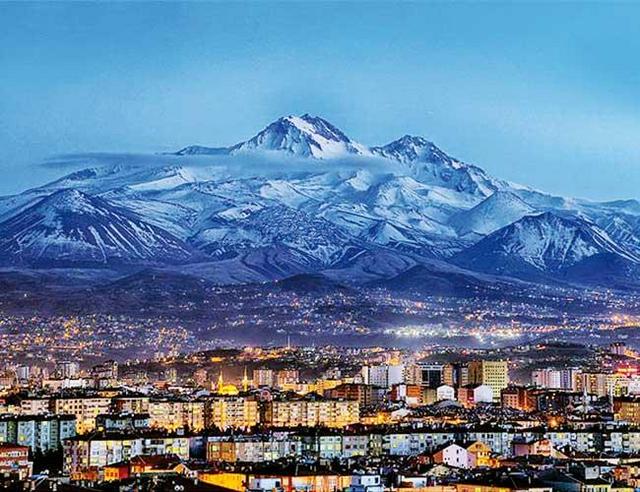

Like Syria, Bythinia was one of the richest and more urbanized areas of the Roman empire, and it offered rich and easy pickings for the Goths. Of its many large cities, there are very few remans visible today as most of these cities have remained inhabited during the Byzantine and Ottoman eras, which has destroyed most archaeological remains. A great earthquake in 1999 cleared the way for archaeological surveys in the Çukurbağ district of İzmit (ancient Nicomedia) and they've brought to life interesting remains of Roman reliefs notable because they still preserve a sizeable part of their original polychromy. Archaeologists think on stylistical grounds that they were probably part of a monument raised in honour to the emperor Septimius Severus in the early III century CE.

Presumably, this large Gothic raid happened when Valerian had already arrived in Antioch. Unwilling to leave the endangered border with the Sasanian empire, Valerian sent a certain officer named Felix with the order to at least secure the city of Byzantium and prevent the Gothic fleet from sailing back. But apparently this was not enough, and in 259 CE he marched in person with most of the eastern army into the north of Anatolia to stabilize the situation. But his reaction had come too late: the Goths had already left, with a rich booty and large amounts of captives, and his army accomplished nothing except becoming affected by an epidemic that was raging in this devastated region; some scholars think that it could be another recurrence of the Plague of Cyprian.

Now that the Roman army and Valerian had departed and were distracted elsewhere (and in difficulties), Šābuhr I seized the opportunity and launched a new attack against Edessa and Carrhae in the spring of 260 CE. Upon receiving this alarming news, Valerian and his diseased army marched again rapidly south to meet this new attack.

While Valerian was busy in the East trying to restore the shattered eastern defenses of Rome in the middle 250s CE, the Goths and their Borani allies began a new series of devastating sea raids against Rome’s Anatolian provinces. As I wrote in a previous post, they obtained the means to do so by their conquest of the Bosporan kingdom in the Crimea, which provided them with a large fleet manned by experienced sailors. Incredible as it could sound, Rome had no naval presence in the Black Sea (except for a very small squadron of light warships based at Byzantium), because until them it had been the navy of their vassal the Kingdom of Bosporus who had protected the Roman shores in this area. This would have disastrous consequences, because the Gothic naval raids would be able to even cross the straits of the Bosporus and Hellespont and enter the Aegean and the Mediterranean as far as the shores of Caria and Lycia. The Roman navy showed an extraordinary lack of ability to react to these raids, which can only be attributed to a conscious decision (or lack of reaction) by the ruling augusti to do nothing in this respect.

The deployment of the Roman fleet had not changed since the time of Augustus except in some minor details. More than half of it (perhaps as much as three quarters of its seaworthy ships) were concentrated in Italy, in the two praetorian fleets at Ravenna and Misenum. These two fleets were commanded by two equestrian officers with the rank of praefecti, who were appointed directly by the emperor. Apart from these two large fleets, the Romans had smaller squadrons at Alexandria, Carthage, Byzantium, the English Channel and perhaps another based at Cyrenaica or Tripolitania (although the existence of this squadron is a matter of debate). And then there were the two river flotillas of the Rhine and Danube. This deployment was obviously designed with two main goals in mind:

- To protect the grain fleets that carried the grain annona from Egypt and Africa into Italy.

- To protect Italy and Rome from sea attacks and more importantly, to ensure that the central government had at any time total control over the fleet; in an empire which had an inner sea at its core this was of the utmost strategical importance, because it ensured that the government in Rome controlled the sea lanes which were the principal means of transportation of the Roman empire. We should only remember how the control over the two praetorian fleets of Ravenna and Misenum was key to the victory of the Senate against Maximinus Thrax in the civil war of 238 CE.

According to Zosimus, in 255 CE a force of Borani landed near the city of Pityus in Colchis (in the southwestern Caucasus coastline, in present-day Georgia, then part of the Roman province of Pontus). They attacked the city, which was then successfully defended by its small garrison under the leadership of its commander Successianus. Again according to Zosimus, upon hearing of this success, Valerian recalled Successianus to Samosata and appointed him as his Praetorian Prefect; Successianus would serve loyally as Valerian’s praefectus praetorio until the end.

But this decision by Valerian had its consequences: again according to Zosimus, the following year the Borani attacked Pityus again and this time they took the city and looted it. This defeat seems to have demoralized the Roman troops in the province of Pontus; assuming that there were many troops in the province to begin with, because usually in ”interior” provinces the Romans kept very small military forces (mostly to act in police duties). According to Zosimus, the fleet of the Borani then sailed westwards along the coast of Pontus until they reached the large city of Trebizond. Again according to Zosimus, the city was walled and had a substantial garrison, but when the Borani launched a surprise night attack against the walls the garrison panicked and fled, and the Borani captured and looted the city.

Valerian seems to have done nothing to defend the population in Pontus, probably because Šābuhr I had launched a new wave of attacks against the Roman eastern border; in 256 CE with mixed results. The Sasanians besieged Circesium without success and besieged and took once again Dura Europos (which they razed to the ground after a dramatic siege, the town became an uninhabited ruin and its dwellers were deported into Ērānšahr, to be settled as colonists in royal lands or to be sold as slaves).

The main attack though seems to have taken place in the traditional scenario of Roman-Sasanian conflicts in northern Mesopotamia, where according to Udo Hartmann and Andreas Goltz Valerian could have won a victory against the army of Šābuhr I; they speculate that perhaps the Sasanian king attacked once again the Roman-held cities of Carrhae and Edessa and Valerian reacted by massing his army and counterattacking with success. Their main proof for such assertion is that the following year the Roman mint of Antiochia issued coins with the legend VICTORIA PART(hica), and that local coins of Alexandria also boasted the Greek legend Nike (Victory). Obviously, this was far more important than defending some cities in northern Asia Minor and Valerian did not hesitate in abandoning their unlucky inhabitants to their fate.

Antoninianus of Valerian; on the reverse, RESTITVTOR ORIENTIS.

This victory seems to have given Valerian enough confidence that he’d finally secured the situation in the East that in the second half of 256 CE he left the East and returned to the West to meet with his son and grandsons and reinforce the image of unity of the imperial collegium (and his own position as senior augustus). Again this would not have been possible if he had not achieved some kind of success that allowed him to feel reasonably confident about leaving things secure in his absence, this reinforces Hartmann and Goltz’s hypothesis. His arrival into the West can be dated securely by an imperial rescript preserved in the Code of Justinian issued by Valerian and dated in the city of Rome on 10 October 256 CE. From Rome he then went to Gaul, where an epigraphic inscription attests to his presence in Colonia Ara Agrippinensis (Cologne) in August 257 CE.

Restitution of Colonia Ara Agrippinensis by the Freanch architect and archaeologist Jean-Claude Golvin.

While his father was in the East, Gallienus had not had en easy time in the West. On departing to the East, Valerian had taken with him large numbers of troops from the European armies, especially from the two Germanias and Raetia, weakening critically the defenses in this area, which included one of the weakest stretches of border in the West, the limes germanicus that ran from near Bonna (modern Bonn in Lower Germany) to near Castra Regina (modern Regensburg) in Raetia. But between 254 and 256/257 CE, his attention seems to have been concentrated on the middle Danubian border; there are very few coins minted in the two Germanias and Raetia but there’s a large number of issues from the mint at Viminacium in Upper Moesia. Apparently his operations there were successful, because already in 254 CE he issued coins with the legend VICTORIA GERM(anica), followed in the following months and years by the legends VICTORIAE, GERMANICUS MAX (imus) and VICTORIA II GERM (anica). Probably the “Germans”against whom Gallienus fought were the Marcomanni, and it’s in this context that Hartmann and Goltz locate the notice given by Aurelius Victor that Gallienus allowed the defeated Marcomanni to settle in Roman soil and took as concubine one of the daughters of their king. Aurelius Victor wrote about this ceremony in an outraged way, and this is just one of the many sources that show open hostility to Gallienus, both Greek and Latin ones; although the Latin senatorial tradition was to remain implacably hostile to the memory of Gallienus until the end.

Antoninianus of Gallienus; on the reverse VICTORIA GERMANICA.

After these successes Gallienus returned to Rome and his presence in this city is attested in September 257 CE, probably to wait for his father’s arrival. The reason for their meeting in the capital was that they wanted to celebrate a double triumph (Valerian’s successes in the East, and Gallienus’in the Danube) and take advantage of the festive and triumphal mood to further secure the future of the Licinian dynasty by raising Valerian the Younger to the rank of caesar. Still in Rome, on 1st January 257 CE, Valerian and Gallienus again took the joint consulship (Valerian’s third, Gallienus’ second) and the mint of Rome issued a series of coins with triumphalist legends like VIRTVS AVGG, VICTORIA PART (hica), VICTORIA GERMANICA, RESTITVTOR ORBIS and FELICITAS AVGG, as well as broadcasting the image of the new caesar.

It was at this time, when the fortunes of the Licinian dynasty appeared brighter than ever, that the two augusti took a controversial decision. Scholars have discussed the issue for decades, but I tend to agree with Hartmann and Goltz that this decision was probably Valerian’s and that Gallienus mainly followed in order to preserve the image of familiar harmony and not rock the boat that they had fought so hard to keep afloat. They issued a decree that was basically a renewal of Decius’ decree on sacrifices and which although it was not specifically targeted against the Christians turned them into its main victims. According to the Acts of the Martyrs, the first effects took place in the summer of 257 CE, so the decree was probably issued at Rome in spring while the two augusti were still residing there.

The summer of 257 CE saw also a renewal in the activities of the imperial family in the borders. Valerian the Younger was sent to the Danube (now that it had been apparently “pacified” by his father) with an encompassing command for the two Pannonias, the two Moesias and Dacia. As he was barely a teenager, his father and grandfather assigned him as a tutor (who was also probably to act as the real commander in the field) an experienced general named Ingenuus about whom practically nothing is known. Meanwhile, both augusti moved to Gaul and settled in Cologne in order to stabilize the situation in the Rhenish border where things had become critical.

The degree of seriousness of the situation can be judged by two means: archaeological evidence and written sources. Archaeology shows that by this time the long limes germanicus, which had been under growing pressure since the time of Severus Alexander finally broke down and most of its forts and watchtowers were destroyed; the Agri Decumates were flooded by the Alamanni and the Roman military presence west and north of the Rhine and Danube practically ceased to exist. The Alamanni were by now known adversaries of the Romans, but they were joined further north by yet another new confederation of Germanic peoples (the Franci, or Franks) in what was yet another disastrous geopolitical development for Rome.

Map of the limes in Upper Germany and Raetia by the end of the II century CE.

According to the IV century CE author Aurelius Victor the Franks crossed the lower Rhine in such numbers that the weakened Roman border garrisons were unable to stop them, and they raided deep and far into Gaul, even crossing the Pyrenées and reaching Hispania. The two augusti reacted by moving immediately into Gaul, where Gallienus apparently obtained some victories, and some coins were quickly issued with the legends GERMANICVS MAX(imus) V and RESTITVTOR GALLIARVM. But to which degree these were really decisive victories is another matter. Archaeological evidence confirms widespread destruction in Germania Superior and Germania Inferior, but further to the west and south the evidence is much more scattered and isolated; rather than layers of destruction what archaeology reveals for many cities in Gaul and Hispania at this time is a widespread and sudden fever for building new city walls, usually at top speed using whatever material were at hand: tombstones, and masonry from funerary monuments and even public buildings. What’s unsure is if this was a reaction to each city suffering a Frankish or Alamannic raid or simply the result of mass hysteria. Aurelius Victor wrote that Tarraco was sacked, but archaeological digs in the modern city show no signs of destruction by this time, but this did not stop nearby Barcino (modern Barcelona) from building a city wall that was totally out of proportion with the importance and size of the city: the pomerium of the town of Barcino had perhaps 1,000 inhabitants, but the wall that was built was the second tallest and strongest in the West after the Aurelian walls of Rome itself.

But things were going to get much worse. By the spring of 258 CE Gallienus was still in Gaul and issuing again a new series of coins with the legend VICT(oria) GERMANICA which scholars are unsure if they can be taken at face value. But at this time devastating news reached him: his son Valerian the Younger (his presumptive heir) had died of natural causes in the Danube. This left the Danube under the overall command of Ingenuus without an imperial presence (always a risky situation) and Gallienus reacted by raising his second son Saloninus to the rank of caesar, although as he was still very young he did not send the boy to the Danube and instead retained him in Gaul at his side.

While the situation in the West worsened by moments, Valerian returned to East, during the end of 257 CE or the start of 258 CE. Again, an imperial rescript preserved in the Code of Justinian attests to his presence in Antiochia in May 258 CE. Despite the worsening situation and the multiplication of foreign threats, Valerian did not abandon his religious policies, and in 258 CE (when he was probably already in the East) he issued a new edict, this time specifically targeted against Christians, who had showed themselves to be the most problematic ones with respect to the previous edict. This second edict targeted directly the hierarchies of the Christian Church (bishops, deacons and presbyters) and explicitly ordained death penalties in the case of refusal to sacrifice; Cyprian of Carthage was one amongst the many victims of this second edict. An interesting point in this edict is that it also ordered harsh punishments against Christian senators and members of the domus caesari (servants of the imperial household) which is a hint at the degree of expansion that the Christian religion had attained even at the top echelons of Roman society.

This time the reason for Valerian’s return to the East doesn’t seem to have been just another wave of Sasanian attacks, but also the increasing scale and severity of Gothic sea raids. According to Zosimus, after seeing the rich booty obtained by their Borani allies, the Goths decided to follow their example and set to the sea in Bosporan ships but with much larger forces. Most alarmingly, the large Gothic fleet managed to cross the Bosporus and land its troops in the Bythinian coast of the sea of Marmara. This Gothic army then proceeded to systematically pillage, burn and destroy all the large and rich cities of Bythinia: Chalcedon, Nicomedia, Nicaea, Kios and Prusa while Cyzicus was spared because torrential rains had turned the Rhyndakos river into barrier that the Goths could not cross. Most alarmingly, and again according to Zosimus (following the lost account of Chrysogonos of Nicomedia) the Goths found ample help by disaffected elements of the civilian population, which eased their task of finding easy goals and weak spots in the defenses.

Like Syria, Bythinia was one of the richest and more urbanized areas of the Roman empire, and it offered rich and easy pickings for the Goths. Of its many large cities, there are very few remans visible today as most of these cities have remained inhabited during the Byzantine and Ottoman eras, which has destroyed most archaeological remains. A great earthquake in 1999 cleared the way for archaeological surveys in the Çukurbağ district of İzmit (ancient Nicomedia) and they've brought to life interesting remains of Roman reliefs notable because they still preserve a sizeable part of their original polychromy. Archaeologists think on stylistical grounds that they were probably part of a monument raised in honour to the emperor Septimius Severus in the early III century CE.

Presumably, this large Gothic raid happened when Valerian had already arrived in Antioch. Unwilling to leave the endangered border with the Sasanian empire, Valerian sent a certain officer named Felix with the order to at least secure the city of Byzantium and prevent the Gothic fleet from sailing back. But apparently this was not enough, and in 259 CE he marched in person with most of the eastern army into the north of Anatolia to stabilize the situation. But his reaction had come too late: the Goths had already left, with a rich booty and large amounts of captives, and his army accomplished nothing except becoming affected by an epidemic that was raging in this devastated region; some scholars think that it could be another recurrence of the Plague of Cyprian.

Now that the Roman army and Valerian had departed and were distracted elsewhere (and in difficulties), Šābuhr I seized the opportunity and launched a new attack against Edessa and Carrhae in the spring of 260 CE. Upon receiving this alarming news, Valerian and his diseased army marched again rapidly south to meet this new attack.

Last edited:

21.4. VALERIAN’S REIGN. THE BATTLE OF EDESSA.

21.4. VALERIAN’S REIGN. THE BATTLE OF EDESSA.

The battle of Edessa, although quite better documented than the battle of Barbalissos, is yet another study in confusion and contradictions between sources. In this post I’ll follow mainly the narrative offered by the Italian scholar Omar Coloru in his short book L’imperatore prigionero: Valeriano, la Persia e la disfatta di Edessa. According to Coloru, Valerian’s army probable took winter quarters in Cappadocia when they were marching back towards Syria from Bithynia and Pontus; he puts forward this hypothesis on the basis of some traces held in ancient accounts and Christian tradition about some troubles (including perhaps an armed uprising by a rich landowner) that happeend around this time and that Coloru suggests that could’ve been caused by the presence of a large body of troops quartered in the province’s cities (the main focus of trouble seems to have been Caesarea Mazaca -the provincial capital- and Tyana).

In the spring, Valerian’s army marched south crossing the Taurus mountains and arrived in northern Syria, where Valerian concentrated his forces on the western side of the Euphrates. The main Sasanian army was not far from there, right on the other side of the river besieging the two large fortified cities of Carrhae and Edessa (each of them located about 80 km east of the river). Coloru proposes that Valerian’s army probably concentrated around Zeugma, for it was the easiest point to cross the river in the immediate environs of the two cities under attack.

Finally though, apparently after some hesitations (according to some of the sources, as we’ll see later) Valerian decided to cross the river and engage Šābuhr I’s army in open battle in the flat plains between Edessa and Carrhae (Coloru proposes Batnae as the exact location for the battle). The battlefield couldn’t have been less suited to the Romans and better suited to the Iranians if Šābuhr I himself had chosen it: a completely flat plain of steppe terrain with hard ground, without boulders, ravines, rivers or hills. It was the perfect terrain for cavalry, and it was in this very same place or very near it where three hundred years earlier the Arsacid general Surena had inflicted a crushing defeat on Crassus’ legions. Now, history was about to repeat himself (by the way, this spot of land was really accursed for the Romans, because again in the 290s the tetrarch Galerius suffered yet another crushing defeat against the army of the Sasanian šāhānšāh Narseh; I know of no other place with such a baneful history for Roman arms).

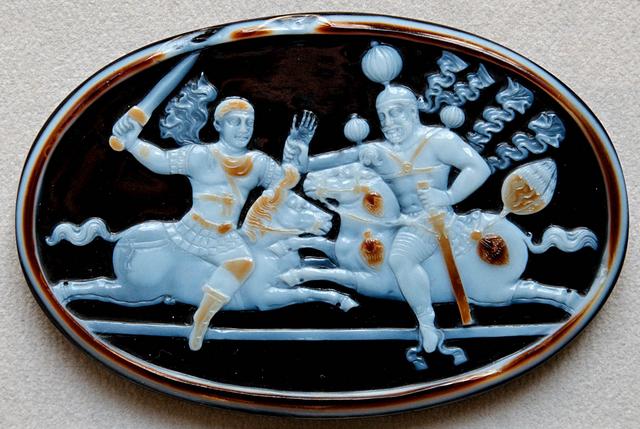

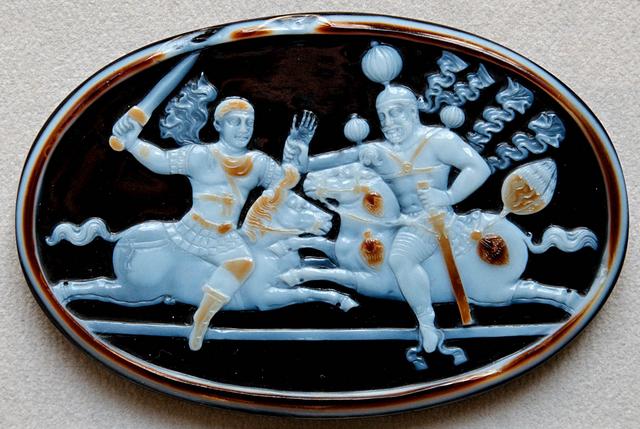

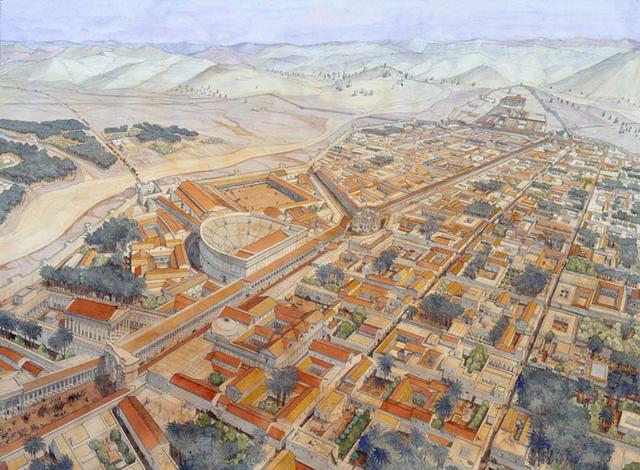

Depiction of Sasanian cavalry at one of Šābuhr I 's triumphal rock reliefs at Bīšāpūr.

About the battle itself, the sources offer a bedazzling array of contradictory accounts. Let’s begin with the Iranian account, according to the ŠKZ:

As usual, Šābuhr I’s account is overly triumphalist (as befits a piece of royal propaganda) and emphasizes exclusively his own role in the event, even stating explicitly that he himself made Valerian prisoner “with our own hands”. Coloru dismisses the number of 70,000 men that the ŠKZ gives for Valerian’s army, but as I wrote in my post about Barbalissos, this number fits within what could have materially possible according to the Roman army in the East (for the complete reasoning, please see the aforementioned post); my only caveat is that perhaps Šābuhr I based his numbers on Roman units at full strength, which is dubious after their long trip into northern Asia Minor and back and the epidemic they’d possibly suffered there (according to Zosimus). It’s again interesting how (like in the case of Gordian III’s army) Šābuhr I gives a complete list of all the “exotic” (for an Iranian) origins of Valerian’s army. It’s clear that the contingents he originally took with him in 254 CE with him to the East from the two Germanias and Raetia were still with him, and that the army counted (like in the case of Gordian III’s army) with contingents of “barbarian” mercenaries, in this case Moors (probably as light cavalry) and Germanic warriors (notice the differentiation in the translation by N.Frye between “Germany” and “Germania”. Given that these lands are quoted in a logical geographical order (from west to east and from north to south, “Germany”refers to the Roman provinces of Upper and Lower Germania while “Germania”refers most probably to Germanic peoples who lived beyond the Danube (most probably Goths).

Rock relief at Naqš-e Rostam depicting the triumph of Šābuhr I over two Roman emperors. Philip the Arab is beging on his knees while Šābuhr I holds Valerian prisoner grasping him by his wrists.

Now let’s take a look at the western sources. As Coloru states, the most detailed and trustworthy source is (bizarrely enough) the XII century Byzantine chronicler John Zonaras. I think it’s interesting enough to quote the passage in its entirety, although it’s quite a long one:

As Zonaras wrote at a point much removed in time from the events and clearly had access to several sources, he chose to list two of these traditions in his own account of events. First Zonaras writes that the Sasanian army initially attacked and besieged Carrhae and Edessa, while Valerian hesitated on the western bank of the Euphrates. What according to Zosimus’ account convinced him to cross the river and attack the army of Šābuhr I was the news that the besieged garrison at Edessa was conducting a vigorous defense and was inflicting many losses on their foes through sorties. This made Valerian confident enough that the Sasanian forces had been weakened in morale and/or numbers and he engaged them in battle. According to Zosimus’ text this was a major blunder, for Šābuhr I’s army was much larger than his own and proceeded to surround and defeat the Romans, taking many of them as prisoners, including Valerian. Then Zosimus presents the other tradition as if it was a different one, although it’s just really a variant of the previous one: while Valerian “was in Edessa” his soldiers were beset by hunger and mutinous, and so Valerian went willingly to Šābuhr I in order to save his own hide. The obvious question to this second tradition is how did Valerian become trapped in Edessa with his army. This could very well have been a result of his defeat on a field battle against the Sasanian army, which forced him and the survivors of his army to take refuge in the besieged city. Quite probably, the city had not enough foodstuffs stored for such a large force and hunger made its appearance, with the soldiers blaming Valerian (rightly or not) for their current predicament.

Amongst the remaining western sources, the Epitome de Caesaribus, Eutropius, Festus, Orosius, Agathias and Evagrius Scholasticus all agree in general lines with the account of the ŠKZ, without adding further details. Evagrius account is particularly valuable, because he employed III century CE sources now lost to us, like Dexippus of Athens and Nikostratos of Trebizond.

The Historia Augusta and Aurelius Victor both state that Valerian was captured by Šābuhr I by means of treachery. According to Aurelius Victor:

And according to the SHA (beware, it’s a long quote and full of all the usual sorts of fabricated letters and quotes that the SHA were so fond of):

The treachery and deviousness of easterners (of which the “Persians” were the quintessential example) was a topoi of Greek and Roman writers since the V century CE, and so it’s abundantly employed in these western sources. As it couldn’t be otherwise, Zosimus also jumped in this bandwagon, and offers a similar account with some minor variations:

The important detail that appears in Zosimus’ account is that apparently Valerian’s army was afflicted by an epidemic. The surviving fragments of the lost work of the VI century CE Eastern Roman author Peter the Patrician also corroborate this version:

Peter the Patrician adds an important bit of information, that the Moorish light cavalry had been badly hit by the plague; we know by the ŠKZ that Valerian’s army did include forces from North Africa, which were probably numeri of Berber light cavalry.

Finally, there’s another group of western accounts that add an important twist to the story. They are all quite short, the longest one belonging to the IX century CE Byzantine chronicler George Syncellus:

The important detail in Syncellus’ account is that there were not one, but two battles. The first one in which the Romans were defeated and ended up being besieged in Edessa. And that after Valerian’s “betrayal”, the rest of his army fought a second battle to try to escape the Sasanian encirclement, which was a partial success. The accounts of Eutropius and Tabarī also corroborate that the battle and Valerian’s capture happened at different moments in time.

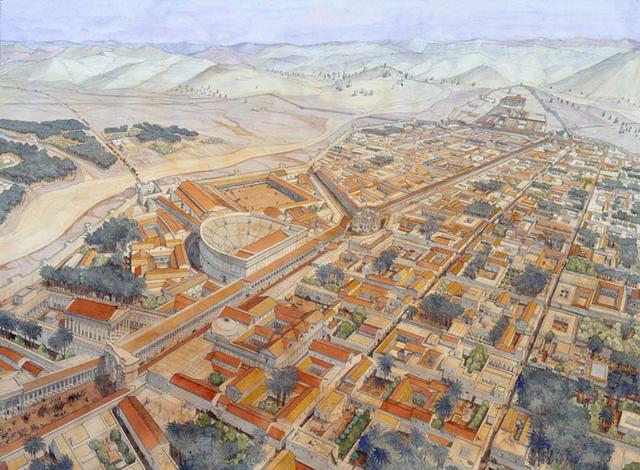

Another triumphal rock relief of Šābuhr I, this time at Bīšāpūr, depicting his triumph over three Roman emperors. Gordian III is shown dead under the hooves of the king's horse, while Philip the Arab is begging on his knees and Valerian is held prisoner by his wrists.

After taking into account all this mess of conflicting accounts, Coloru offers the following reconstruction of events, which I find quite reasonable: after an initial hesitation, upon hearing about the vigorous defense of Edessa by its Roman garrison, Valerian decided to cross the Euphrates to attack the besiegers. Both armies met probably near Batnae between Carrhae, Edessa and Euphrates. There, the Roman army suffered an enveloping maneuver by the army of Šābuhr I and was defeated, but it somehow managed to retreat into Edessa and take refuge behind its formidable fortifications; Valerian went along with the army. The went on for an indeterminate amount of time, with conditions growing increasingly dire for the besieged Romans. Edessa had enough foodstuffs to sustain a siege only for its normal garrison plus its usual inhabitants, but not for the extra mouths provided by Valerian’s defeated army. In addition, given the unsanitary conditions of a besieged city in the heat of the Mesopotamian summer crammed with so many men and beasts, an epidemic broke out which would have hit specially hard the light Moorish cavalry, which was a key element of Valerian’s army if he wanted to defeat the powerful Sasanian cavalry. As a result of this situation the trapped Roman troops began to adopt a mutinous attitude, and Valerian felt that his only way out of the mass was to try to negotiate a peace with the Sasanian king.

Coloru notes how this situation has several parallels in the previous history of conflicts between the Romans and the Iranian empires: after his defeat at Carrhae Crassus was also forced to negotiate with Surena by his own soldiers who threatened his life if he refused to do so, and it’s quite possible that the death of Gordian III happened in similar circumstances after his defeat at Misikhe.

But knowing full well that the situation of the besieged Romans was becoming desperate, Šābuhr I refused to talk with Valerian’s embassy and demanded that the augustus himself came to ask for peace in person. Valerian had no other options left, and went to meet Šābuhr I, and during this meeting, in unknown circumstances Valerian and his entire entourage were taken prisoners by Šābuhr I.

In broad lines, this reconstruction agrees both with the ŠKZ and with most Graeco-Roman sources. For the “Mazda-worshipping lord” Šābuhr I, writing a blatant lie in his great triumphal inscription would have been a delicate matter, but omissions and half-truths would’ve been another matter altogether, so probably, like with the account of his victory over Gordian III and Mishike sixteen years earlier, the šāhānšāh embellished things a bit without resorting to open lies. There was most probably a “great field battle” between his army and the Romans, in which Šābuhr I was victorious. And in according to Coloru’s reconstruction, the Sasanian king did take Valerian prisoner “with his own hand”, but the ŠKZ does to make explicit the exact circumstances in which this capture took place (it would have looked a bit bad for PR reasons, and so the text implies that Šābuhr I did the capture on his own heroically in the midst of the battle). And anyway, Šābuhr I probably reasoned that after all it was his victory in battle which had forced Valerian to come to ask him for peace terms, so what he was telling was “basically” the truth (again, a delicate matter for a Zoroastrian king).

On the other side, most western authors did focus their accounts exclusively on the “treachery”of the “perfidious” easterners, trying to sidestep the fact that the Roman army had been beaten yet again by Šābuhr I in open battle. It’s important to notice how this refusal to accept reality and call things by their name is again the same attitude that can be found in the (scarce) western accounts of Gordian III’s campaign and Barbalissos.

Cameo of Roman-Iranian facture preserved at the Cabinet des Medailles in Paris, depicting Valerian being captured in battle by Šābuhr I, "with his own hand". Notice how Šābuhr I doesn't even need to unsheath his sword to capture the hapless Roman emperor.

The blow and impact of Valerian’s capture was enormous, and without precedents in Roman history. Neither Abrittus nor Barbalissos can compare; this was the first (and only) time in history that a Roman augustus was captured alive and paraded around like a living trophy by a foreign enemy (well, there’s also the case of Romanos IV Diogenes after Manzikert) and the impact of this news fell like a thunderclap all across the roman empire (and probably its neighbors as well). The only other event in ancient Roman history that can be compared to Valerian’s capture in its wholesale impact was the sack of Rome by Alaric in 410 CE; not even the Roman defeat at Adrianople came close.

It also marked the absolute nadir of Roman fortunes in the III century, and the beginning of the darkest decade of the long III century “crisis”, that saw the separation of two large parts of the empire (the Gallic empire and the Palmyrene empire) and the almost definitive disintegration of Rome as a political entity. A reign that had begun with such high hopes and that for a short moment had looked like it had succeeded in stabilizing the empire and containing the foreign threats ended in absolute disaster and utter humiliation.

Valerian’s capture at Edessa was a political catastrophe, but ironically from a purely military point of view, it was probably a lesser defeat than Barbalissos seven years earlier. Even the ŠKZ implies it, because this time it did not use to expression “annihilate” to refer to this battle, and used just the word “defeat”. Part of the Roman army of the East survived, as did some of Valerian’s high officials, and unlike in 253 CE, this time in his following invasion of the Roman eastern provinces the Sasanian king did encounter organized resistance by Roman military units.

But nevertheless, Šābuhr I’s victory was again mind-blowing. Along with Valerian, the ŠKZ states that the Sasanian king captured the praetorian prefect as well as “chiefs of the army” and “senators”. The praetorian prefect was probably Successianus, but about the rest of military commanders and senators scholars have no clue about their identities.

Valerian’s memory was tarnished forever for the dishonor he brought upon Rome by allowing himself to be captured alive, and most Graeco-Roman historical records fulminate against him for this reason, although there are some exceptions like Zosimus. And the reason why Zosimus did not criticize him too badly was the very same one why another (much larger) part of ancient chroniclers redoubled their criticism against Valerian: he had been a persecutor of Christians. Already in the early IV century CE, the Christian writer Lactantius wrote with glee about Valerian’s dishonor and his humiliating captivity in his work De mortibus persecutorum:

The V century CE Christian writer Orosius wrote about Valerian’s captivity in similar terms in his Adversus paganos:

And the VI century CE East Roman author Agathias also implied that Valerian suffered terrible humiliations at the hands of Šābuhr I:

Lactantius’ writing has caused rivers of ink to flow for the past two centuries amongst scholars. Some scholars think it’s merely Christian propaganda, while others see grounds for believing there’s some truth in it. What happened to Valerian after his capture? The ŠKZ is explicit: Valerian, his commanders, high officials and soldiers were all deported to Pārs, the homeland of the Sasanian dynasty. And both eastern accounts and archaeological evidence support this.

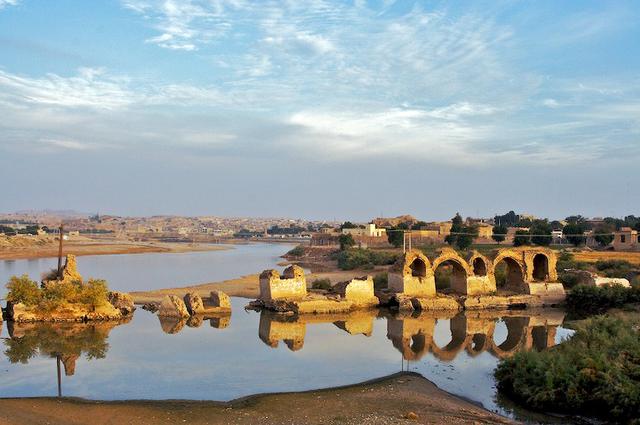

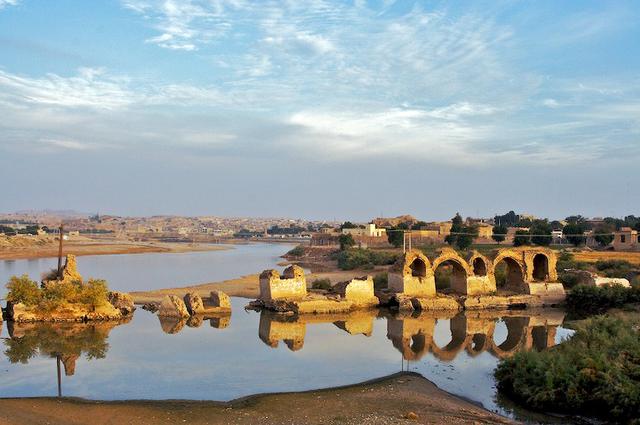

The X century CE Chronicle of Seert (an Arabic chronicle using older materials written in Aramaic dating from Sasanian times) written in Iraq (and so within the old lands of the Sasanian empire) state that the deportees were mainly settled in royal estates in Asōrestān and Xūzestān (contradicting the ŠKZ), but this tradition is also supported by Tabarī, according to whom Valerian and the rest of prisoners were settled in one of the new cities founded by Šābuhr I, Wēh-Andiyok-Šābuhr (literally, “the better Antioch of Šābuhr”), which in a short time became corrupted into Gondēšāpur. Tabarī also adds that Šābuhr I ordered Valerian to organize the construction of an irrigation dam in the environs of Šūštar, which is know still today as “Caesar’s dam” by the local population (Band-e Qayṣar, on the Kārūn river). The technical skills of Roman soldiers and engineers were much appreciated by successive Sasanian kings and is possible they always settled them in undeveloped royal estates to take advantage of said skills.

On another side, it’s also possible that according to the ŠKZ Valerian spent his captivity in Pārs; in this case the most likely place is the city founded by Šābuhr I as his capital city in his homeland (he did not use Ardaxšir-Xwarrah as his royal residence), the city of Wēh-Šābuhr (“Lord Šābuhr” in Middle Persian, which has become Bīšāpūr in New Persian). Here, Šābuhr I built a large complex with a palace and a temple to the goddess Anāhīd which shows clear signs of Roman influence.

Remains of the dam's bridge known as Band-e Qayṣar (Caesar's dam) at Šūštar in Khuzestan.

About the question of the treatment of Valerian during his captivity and after, I tend to agree with Coloru that there are enough grounds to believe that Lactantius’ account is not a mere fabrication born out of sectarian hatred. For starters, Firdawsī’s Šāh-nāmah states that king Šābuhr menaced Valerian with skinning him if he disobeyed his orders; afterwards he had his ears and nose cut and then he threw him into prison in chains. The story about Valerian’s mutilation is also found in Tabarī. In Achaemenid and Sasanian tradition, a man with deformities or a mutilated body could not be king (and the same was ready among the Romans, at least in Byzantine times, the story of Justinian II “Rhinotmetos” is conclusive enough). So, although it’s impossible to proof it one way or another, the story could have a firm basis in historical realities. The Epitome de Caesaribus adds the quite mysterious remark that after his capture Valerian was referred to as colobius. Linguistic research has come to the conclusion that this Latin words could be a direct transliteration of the Greek adjective kolobós, meaning “mutilated”.

A similar thing happens with his alleged function as a footstool for Šābuhr I when the king wanted to mount his horse. The Seleucid king Demetrios II was exhibited in chains across the Arsacid empire after his defeat by Mihrdād II the Great in 138 BCE, and in 293 CE the Sasanian king Narseh inflicted a similar punishment against the nobleman Wahnam (he was exhibited across the empire chained and mounted on a donkey). It’s possible that Valerian suffered a similar fate and that Lactantius twisted it a bit to give it a Biblical flavor, as stated by Psalm 110,1:

As for the skinning, it’s also probably true or at least with a strong basis in historical realities. A 2012 study by Robert Bolliger and Josef Wiesehöfer has brought into relief the continuity of skinning as a punishment among several near eastern and iranian dynasties across ancient times. It was a common punishment in Achaemenid times for very serious crimes (usurpation, rebellion, etc.), and in his Bīsotūn inscription Darius I stated that this was the punishment inflicted on the rebel Fravartiš (after being impaled) who had tried to become king of Media. This gruesome practice is first attested among the Assyrians, and most specifically under Sargon II, who executed a vassal king who had rebelled and then had the corpse skinned and the skin tanned in red color (the very same punishment described by Lactantius). In Sasanian times, the same fate was met by the prophet Mani under Bahrām I, by the Christian martyrs Barshebya and Simeon under Šābuhr II and by the army general Naxwaragān under Xusrō I (this time without the previous nicety of an execution, according to Agathias). Also, at least in the cases of Sargon II and Darius I, the skins of their defeated enemies were specially treated so that they would be preserved for a long time as a memory of what happened to rebels and usurpers.

The battle of Edessa, although quite better documented than the battle of Barbalissos, is yet another study in confusion and contradictions between sources. In this post I’ll follow mainly the narrative offered by the Italian scholar Omar Coloru in his short book L’imperatore prigionero: Valeriano, la Persia e la disfatta di Edessa. According to Coloru, Valerian’s army probable took winter quarters in Cappadocia when they were marching back towards Syria from Bithynia and Pontus; he puts forward this hypothesis on the basis of some traces held in ancient accounts and Christian tradition about some troubles (including perhaps an armed uprising by a rich landowner) that happeend around this time and that Coloru suggests that could’ve been caused by the presence of a large body of troops quartered in the province’s cities (the main focus of trouble seems to have been Caesarea Mazaca -the provincial capital- and Tyana).

In the spring, Valerian’s army marched south crossing the Taurus mountains and arrived in northern Syria, where Valerian concentrated his forces on the western side of the Euphrates. The main Sasanian army was not far from there, right on the other side of the river besieging the two large fortified cities of Carrhae and Edessa (each of them located about 80 km east of the river). Coloru proposes that Valerian’s army probably concentrated around Zeugma, for it was the easiest point to cross the river in the immediate environs of the two cities under attack.

Finally though, apparently after some hesitations (according to some of the sources, as we’ll see later) Valerian decided to cross the river and engage Šābuhr I’s army in open battle in the flat plains between Edessa and Carrhae (Coloru proposes Batnae as the exact location for the battle). The battlefield couldn’t have been less suited to the Romans and better suited to the Iranians if Šābuhr I himself had chosen it: a completely flat plain of steppe terrain with hard ground, without boulders, ravines, rivers or hills. It was the perfect terrain for cavalry, and it was in this very same place or very near it where three hundred years earlier the Arsacid general Surena had inflicted a crushing defeat on Crassus’ legions. Now, history was about to repeat himself (by the way, this spot of land was really accursed for the Romans, because again in the 290s the tetrarch Galerius suffered yet another crushing defeat against the army of the Sasanian šāhānšāh Narseh; I know of no other place with such a baneful history for Roman arms).

Depiction of Sasanian cavalry at one of Šābuhr I 's triumphal rock reliefs at Bīšāpūr.

About the battle itself, the sources offer a bedazzling array of contradictory accounts. Let’s begin with the Iranian account, according to the ŠKZ:

In the third campaign, when we attacked Carrhae and Urhai (Edessa) and were besieging Carrhae and Edessa Valerian Caesar marched against us. He had with him a force of 70,000 from Germany, Raetia, Noricum, Dacia, Pannonia, Moesia, Istria, Spain, Africa (?), Thrace, Bithynia, Asia, Pamphylia, Isauria, Lycaonia, Galatia, Lycia, Cilicia, Cappadocia, Phrygia, Syria, Phoenicia, Judaea, Arabia, Mauritania, Germania, Rhodes (Lydia), Osrhoene and Mesopotamia.

And beyond Carrhae and Edessa we had a great battle with Valerian Caesar. We made prisoner ourselves with our own hands Valerian Caesar and the others, chiefs of that army, the praetorian prefect, senators; we made all prisoners and deported them to Persis.

As usual, Šābuhr I’s account is overly triumphalist (as befits a piece of royal propaganda) and emphasizes exclusively his own role in the event, even stating explicitly that he himself made Valerian prisoner “with our own hands”. Coloru dismisses the number of 70,000 men that the ŠKZ gives for Valerian’s army, but as I wrote in my post about Barbalissos, this number fits within what could have materially possible according to the Roman army in the East (for the complete reasoning, please see the aforementioned post); my only caveat is that perhaps Šābuhr I based his numbers on Roman units at full strength, which is dubious after their long trip into northern Asia Minor and back and the epidemic they’d possibly suffered there (according to Zosimus). It’s again interesting how (like in the case of Gordian III’s army) Šābuhr I gives a complete list of all the “exotic” (for an Iranian) origins of Valerian’s army. It’s clear that the contingents he originally took with him in 254 CE with him to the East from the two Germanias and Raetia were still with him, and that the army counted (like in the case of Gordian III’s army) with contingents of “barbarian” mercenaries, in this case Moors (probably as light cavalry) and Germanic warriors (notice the differentiation in the translation by N.Frye between “Germany” and “Germania”. Given that these lands are quoted in a logical geographical order (from west to east and from north to south, “Germany”refers to the Roman provinces of Upper and Lower Germania while “Germania”refers most probably to Germanic peoples who lived beyond the Danube (most probably Goths).

Rock relief at Naqš-e Rostam depicting the triumph of Šābuhr I over two Roman emperors. Philip the Arab is beging on his knees while Šābuhr I holds Valerian prisoner grasping him by his wrists.

Now let’s take a look at the western sources. As Coloru states, the most detailed and trustworthy source is (bizarrely enough) the XII century Byzantine chronicler John Zonaras. I think it’s interesting enough to quote the passage in its entirety, although it’s quite a long one:

Furthermore, the Persians, when Shapur was their king, overran Syria, ravaged Cappadocia, and besieged Edessa. Valerian hesitated to engage with the enemy. But, learning that the soldiers in Edessa were making vigorous sorties against the barbarians, killing many of them and capturing vast quantities of booty, he gained new courage. He went forth with the forces at his disposal and engaged with the Persians. But they, being many times more numerous, surrounded the Romans; the greater number (of the Romans) fell, but some fled, and Valerian and his retinue were seized by the enemy and led away to Shapur. Now that he was master of the emperor, Shapur thought that he was in control of everything; and, cruel as he was before, he became much worse afterwards. Such was the manner in which Valerian was taken prisoner by the Persians, as recorded by some authors. But there are those who say that Valerian willingly went to the Persians because during his stay in Edessa his soldiers were beset by hunger. They then became seditious and sought to destroy their emperor. And he, in fear of the soldiers' insurrection, fled to Shapur so that he might not be killed by his own people. He surrendered (not only) himself to his enemy but, as far as it was in his power, the Roman army. The soldiers were not destroyed but learnt of his betrayal and fled, and (only) a few were lost. Whether the emperor was captured in war by the Persians or whether he willingly entrusted himself to them, he was treated dishonourably by Shapur. The Persians attacked the cities in complete freedom from fear, and took Antioch on the Orontes and Tarsus, the most notable of the cities in Cilicia, and Caesarea in Cappadocia. As they led away the multitude of prisoners they did not give them more than the minimum amount of food needed to sustain life, nor did they allow them a sufficient supply of water, but once a day their guards drove them to water like cattle. Caesarea had a large population (for four hundred thousand men are said to dwell in it) and they did not capture it, since the inhabitants nobly resisted the enemy and were commanded by a certain brave and intelligent Demosthenes, until a certain doctor was taken prisoner. He was unable to bear the torture inflicted upon him and revealed a certain site from which during the night the Persians made their entrance and destroyed everyone. But their general Demosthenes, although encircled by many Persians who were under orders to take him alive, mounted his horse and raised aloft an unsheathed sword. He forced his way into the midst of the enemy; and, striking down very many, he escaped successfully from the city.

As Zonaras wrote at a point much removed in time from the events and clearly had access to several sources, he chose to list two of these traditions in his own account of events. First Zonaras writes that the Sasanian army initially attacked and besieged Carrhae and Edessa, while Valerian hesitated on the western bank of the Euphrates. What according to Zosimus’ account convinced him to cross the river and attack the army of Šābuhr I was the news that the besieged garrison at Edessa was conducting a vigorous defense and was inflicting many losses on their foes through sorties. This made Valerian confident enough that the Sasanian forces had been weakened in morale and/or numbers and he engaged them in battle. According to Zosimus’ text this was a major blunder, for Šābuhr I’s army was much larger than his own and proceeded to surround and defeat the Romans, taking many of them as prisoners, including Valerian. Then Zosimus presents the other tradition as if it was a different one, although it’s just really a variant of the previous one: while Valerian “was in Edessa” his soldiers were beset by hunger and mutinous, and so Valerian went willingly to Šābuhr I in order to save his own hide. The obvious question to this second tradition is how did Valerian become trapped in Edessa with his army. This could very well have been a result of his defeat on a field battle against the Sasanian army, which forced him and the survivors of his army to take refuge in the besieged city. Quite probably, the city had not enough foodstuffs stored for such a large force and hunger made its appearance, with the soldiers blaming Valerian (rightly or not) for their current predicament.

Amongst the remaining western sources, the Epitome de Caesaribus, Eutropius, Festus, Orosius, Agathias and Evagrius Scholasticus all agree in general lines with the account of the ŠKZ, without adding further details. Evagrius account is particularly valuable, because he employed III century CE sources now lost to us, like Dexippus of Athens and Nikostratos of Trebizond.

The Historia Augusta and Aurelius Victor both state that Valerian was captured by Šābuhr I by means of treachery. According to Aurelius Victor:

For when his father (i.e. Valerian) was conducting an indecisive and long war in Mesopotamia, he was ambushed by a trick of the king of the Persians called Shapur and was ignominiously hacked to death in the sixth year of his reign while still vigorous for his old age.

And according to the SHA (beware, it’s a long quote and full of all the usual sorts of fabricated letters and quotes that the SHA were so fond of):

... to Shapur, Velsolus, king of kings, `Did I but know for a certainty that the Romans could be wholly defeated, I should congratulate you on the victory of which you boast. But inasmuch as that nation, either through Fate or its own prowess, is all-powerful, look to it lest the fact that you have taken prisoner an aged emperor, and that indeed by guile, may turn out ill for yourself and your descendants. Consider what mighty nations the Romans have made their subjects instead of their enemies after they had often suffered defeat at their hands. We have heard, in fact, how the Gauls conquered them and burned that great city of theirs; it is a fact that the Gauls are now servants to the Romans. What of the Africans? Did they not conquer the Romans? It is a fact that they serve them now. Examples more remote and perhaps less important I will not cite. Mithridates of Pontus held all of Asia; it is a fact that he was vanquished and Asia now belongs to the Romans. If you ask my advice, make use of the opportunity for peace and give back Valerian to his people. I do indeed congratulate you on your good fortune, but only if you know how to use it aright.'

Velenus, king of the Cadusii, wrote as follows: `I have received with gratitude my forces returned to me safe and sound. Yet I cannot wholly congratulate you that Valerian, prince of princes, is captured; I should congratulate you more, were he given back to his people. For the Romans are never more dangerous than when they are defeated. Act, therefore, as becomes a prudent man, and do not let Fortune, which has tricked many, kindle your pride. Valerian has an emperor for a son and a Caesar for a grandson, and what of the whole Roman world, which, to a man, will rise up against you? Give back Valerian, therefore, and make peace with the Romans, a peace which will benefit us as well, because of the tribes of Pontus.' Artavasdes, king of the Armenians, sent the following letter to Shapur: `I have, indeed, a share in your glory, but I fear that you have not so much conquered as sown the seeds of war. For Valerian is being sought back by his son, his grandson, and the generals of Rome, by all Gaul, all Africa, all Spain, all Italy, and by all the nations of Illyricum, the East, and Pontus, which are leagued with the Romans or subject to them. So, then, you have captured one old man but have made all the nations of the world your bitterest foes, and ours too, perhaps, for we have sent you aid; we are your neighbours, and we always suffer when you fight with each other.' The Bactrians, the Hiberians, the Albanians, and the Tauroscythians refused to receive Shapur's letters and wrote to the Roman commanders, promising aid for the liberation of Valerian from his captivity.

The treachery and deviousness of easterners (of which the “Persians” were the quintessential example) was a topoi of Greek and Roman writers since the V century CE, and so it’s abundantly employed in these western sources. As it couldn’t be otherwise, Zosimus also jumped in this bandwagon, and offers a similar account with some minor variations:

Valerian had by this time heard of the disturbances in Bithynia, but he dared not to confide the defence of it to any of his generals through distrust. He therefore sent Felix to Byzantium, and went in person from Antioch into Cappadocia, and he returned after he had done some injury to every city through which he passed. But the plague then attacked his troops, and destroyed most of them, at the time when Shapur made an attempt upon the east, and reduced most of it into subjection. In the meantime, Valerian became so weak that he despaired of ever recovering from the present sad state of affairs, and tried to conclude the war by a gift of money. Shapur, however, sent back empty-handed the envoys who were sent to him with that proposal, and demanded that the emperor come and speak with him in person concerning the affairs he wished to negotiate. Valerian most imprudently consented, and, going incautiously to Shapur with a small retinue to discuss the peace terms, was presently seized by the enemy, and so ended his days in the capacity of a slave among the Persians, to the disgrace of the Roman name in all future times.

The important detail that appears in Zosimus’ account is that apparently Valerian’s army was afflicted by an epidemic. The surviving fragments of the lost work of the VI century CE Eastern Roman author Peter the Patrician also corroborate this version:

Valerian, wary of the Persian attack when his army, particularly the Moors, was afflicted with the plague, amassed an immense amount of gold and sent ambassadors to Shapur, in the hope of bringing an end to the war through lavish gifts. Shapur heard about the plague and was greatly elated by Valerian's request. He kept the ambassadors waiting, then dismissed them without success in their mission and immediately set out in pursuit.

Peter the Patrician adds an important bit of information, that the Moorish light cavalry had been badly hit by the plague; we know by the ŠKZ that Valerian’s army did include forces from North Africa, which were probably numeri of Berber light cavalry.

Finally, there’s another group of western accounts that add an important twist to the story. They are all quite short, the longest one belonging to the IX century CE Byzantine chronicler George Syncellus:

During their (i.e. Valerian and Gallienus) reign, Shapur, the king of the Persians, laid waste to Syria and captured Antioch and also ravaged Cappadocia. The Roman army was afflicted by famine in Edessa and as a result was in a mutinous mood. Valerian, thoroughly scared and pretending that he was going into another battle, surrendered himself to Shapur, the king of the Persians, and agreed to betray the main body of his forces. When the Romans got wind of this, they escaped with difficulty and some of them were killed. Shapur pursued them and captured the great Antioch, Tarsus in Cilicia and Caesarea in Cappadocia.

The important detail in Syncellus’ account is that there were not one, but two battles. The first one in which the Romans were defeated and ended up being besieged in Edessa. And that after Valerian’s “betrayal”, the rest of his army fought a second battle to try to escape the Sasanian encirclement, which was a partial success. The accounts of Eutropius and Tabarī also corroborate that the battle and Valerian’s capture happened at different moments in time.

Another triumphal rock relief of Šābuhr I, this time at Bīšāpūr, depicting his triumph over three Roman emperors. Gordian III is shown dead under the hooves of the king's horse, while Philip the Arab is begging on his knees and Valerian is held prisoner by his wrists.