Welcome forum viewers, @Trin Tragula and @Arheo ,

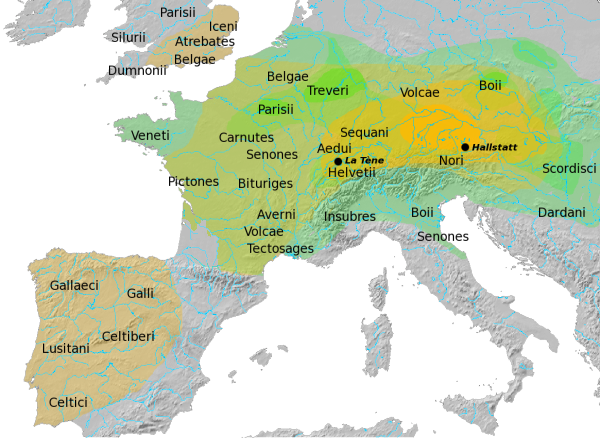

Today @vanin and I are going to explore the ‘filthy barbarians’ of the cold north – also known as Germanics - with you. We decided to do this to write an overview of the ‘Germanic’ archaeology and written sources of the Pre-Roman Iron Age (pRIA) for all who are interested, to propose several improvements for Imperator’s map and to counter some misconceptions that have been circulating. Among these are this map of the pRIA, in which the House Urns culture, which vanished between 525 and 450 BC and wasn't a contemporary of the Oksywie culture, and a large gap between the Harpstedt-Nienburger and La Tène cultures is shown, although there were many findings in the latter region. The Harpstedt-Nienburger concept is also not very appropriate for the period of our interest, as it describes some inhomogeneous groups sharing two pottery styles of the middle pRIA (570 to 330 BC). Additionally, some space will be devoted to discussing the myths that are still overvalued by some in comparison to archaeological evidence.

To summarise this quite long thread:

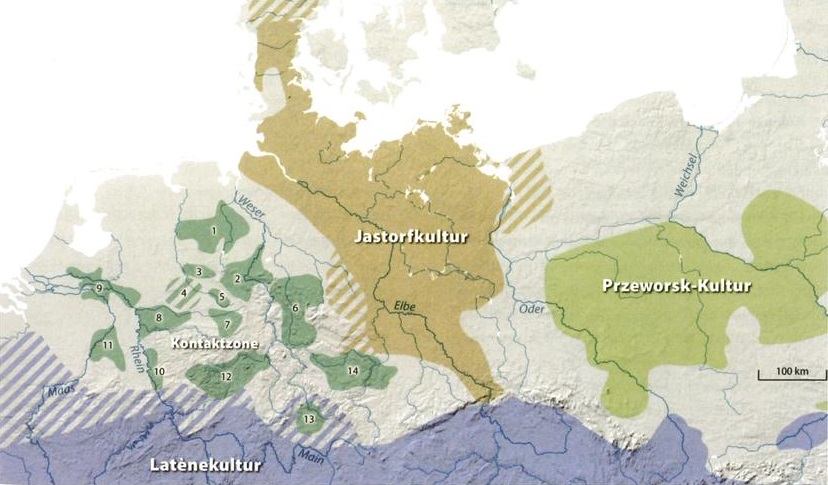

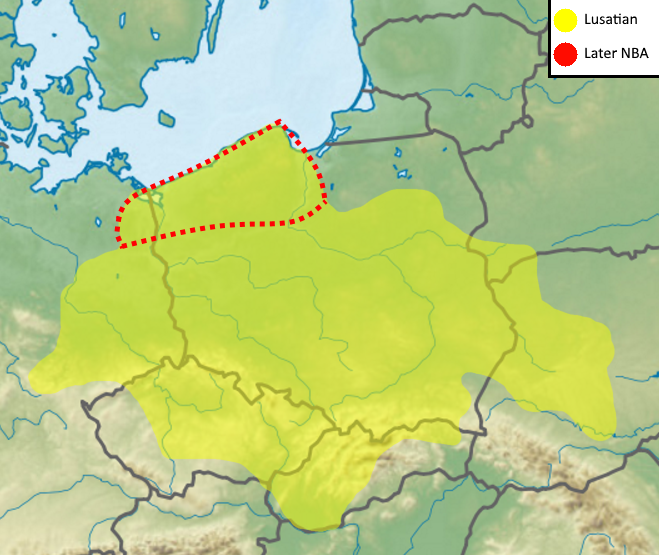

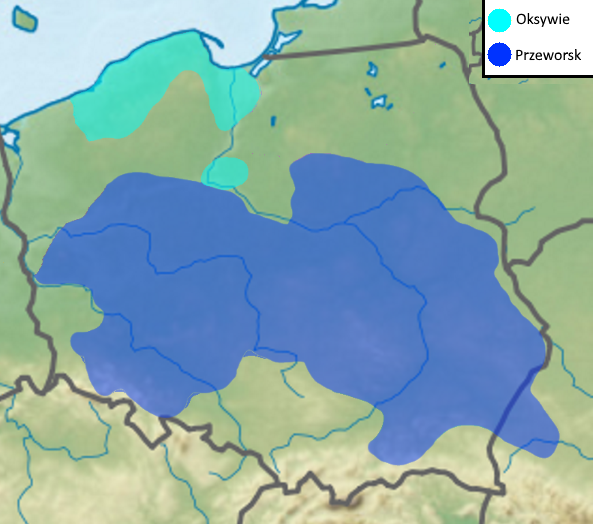

Starting with what Germanics actually were in the view of ancient authors and our more modern interpretation, Germanics are introduced as speaking a Germanic language because there was not one but there were many ‘Germanic’ archaeological cultures; bilingualism is discussed in this regard, too. This is followed by the archaeology of four regions. Firstly, the north-east of Germany with the Jastorf culture, its peripheries and its expansion to the south, which lead to the replacement of the House Urns culture, are discussed. This is followed by the north-west of Germany and the Netherlands, which both built a quite inhomogeneous Contact Zone between the La Tène and Jastorf cultures. This zone was more advanced than Jastorf, and a strong Celtic influence on the region’s tribal names might indicate bilingualism there.

In the second part written by @vanin , the archaeology of Poland and Scandinavia is going to outlined. The section on Poland is centred around the question of what evidence there is that Germanics lived in the area, as well as around the Celtic influence and appearance of Celtic religious practices. Thereafter, the Scandinavian part is made up of Jutland’s relation to the Jastorf culture and the remote character of the Scandinavian peninsula for the first half of Imperator’s time frame. An ansatz for a Swedish and Norwegian setup based on ancient sources is proposed, as overemphasizing the medieval accounts of Jordanes and the medieval names of particular Swedish and Norwegian regions leads to the wrong impression that the Vikings had been living on the Scandinavian peninsula since time immemorial.

The proposed setup would look like this:

Who was Germanic?

Inventing a culture is a deed not many can claim, but Caesar did exactly this in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico. There he simply called everyone from east of the Rhine Germanic opposed to the Gauls west of the Rhine. When he describes the 'lifestyle' of these tribes, differences between his so-called Germans become apparent, e.g. he states that the Suebians lived only in small villages whereas the Ubians are described to have lived in oppida.

Caesar's definition of culture based on geography is far from our modern culture term, however. We consider customs, behaviour and language indicative for a somewhat abstract culture. Neither of these are easily accessible to us, as we lack self-written sources and we certainly do not know how many and who spoke which or what language. Archaeology can somewhat help us with customs, but we only see the unanimated used objects and not what was done with them.

Therefore, for the purposes of this text, a Germanic will be considered to be a person who spoke a Germanic language. This may sound straightforward, but not so, for many people in the past may have spoken more than a single language, one in their immediate community and another for communication with more distant neighbours. If Germanic was the language of the family, then they might be reasonably regarded as Germanic, but if they used Germanic only as a lingua franca to facilitate external interactions, then should they be called Germanic? Probably not. Otherwise in transitional regions, there might have been proper bi-lingual areas where two languages (or even more) were used on a daily basis. What were they? Probably calling them Celto-Germanic, Germano-Celtic or there like might be an appropriate way. As they need to be part of one culture group for in-game purposes, we can look to archaeology and determine whether or not they were closer to one group or to another one.

Short overview over the early Germanic language

Archaeology of ‘Germanics’ and Germanic Tribes

For a long time, there was the assumption that a unified archaeological culture would indicate a unified culture and language of these people, however in modern times this is no longer thought to be true. Transition zones are included in modern models.

When it comes to who lived there then we only know about people living in these areas from ancient sources. The first mentions of Germanic tribes dates to the first century BC, when Caesar campaigned in Gaul. As a huge part of the map would be uninhabited if one would only use certain information, PDX chose to extrapolate from the first mention back to our start date. Archaeology is a good indicator to track down any major population shifts or migrations from or to an area. What one shouldn’t forget is that such a fickle society also means that names could change, but they are the only names we have so it’s not that wrong to use a possibly later name for the same people (from whom that later name also emerged). This is however no longer possible when one has names like Heruli who seem to emerge from a mix of Sarmatian, continental Germanic (Goths) and Jutish people (possibly also others). In such a situation, using the name would lead to the wrong impression of a long-standing continuity that did not exist.

North-Eastern Germany and the Jastorf Culture

Since its introduction over a hundred years ago, the Jastorf culture has become a well-accepted concept. The Jastorf culture lasted from around 600 BC up to Christ’s birth and developed from the local Bronze Age culture with settlements and graveyards were continuing to be used throughout the transition. Nowadays, it is divided into two periods I (divided into a, b, c, d) and II (divided into a, b, c, d) of which the latter is characterised by southern influence from the La Tène culture; there was still influence from the Celtic south in the first phase, however. A century ago the second phase was divided in two and named Ripdorf (300 BC to 150 BC) and Seedorf (150 BC to 1 AD), but this would imply a major cultural shift that didn’t occur. La Tène culture mostly impacted the pottery, some tools and some jewellery (see [1.1]), while other cultural elements such as burial rites did not change in the long run.

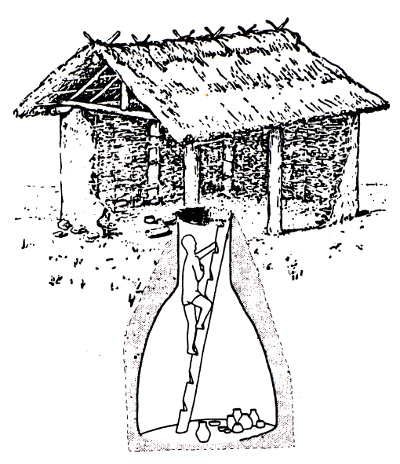

Jastorf’s characteristics are (apart from its pottery, tools and jeweller), cremation followed by burial the urn with the remnants in a simple earthen pit. During the early phase of La Tène influence other burial rites appeared, but vanished soon afterwards, leaving only the ‘ordinary’ Jastorf burial practice. Because all burials are the same until the 1st century BC, Jastorf is often considered to be a very egalitarian society with no clear elite. The burial sites are often very large in the core territory (see section about subdivision), e.g. Mühlen-Eichsen is the largest one with about 5000 burials (c. [1.2]). In its southern periphery (see section about subdivision) the cemeteries are smaller with Chörau being the exception. The Jastorf people lived in three-aisled byre-dwellings in its core territory, whereas the people lived in pit-houses in the southern periphery.

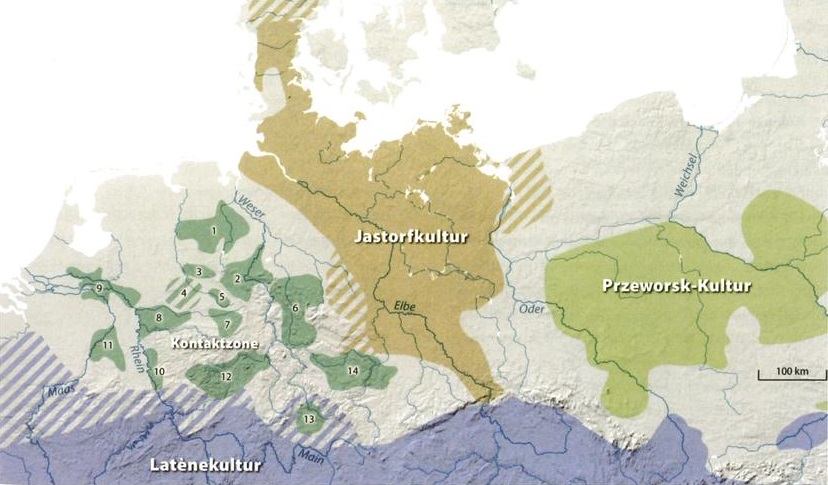

From [2.1]

There are some concepts about how to divide the Jastorf culture spatially (see figure "Divisions of Jastorf", [1.3]), but its core territory is north-eastern Germany, from which it expanded westwards, southwards and into Jutland. The southern periphery came into being at the end of the 6th century BC and replaced the preceding House-Urns culture. It is nearly identical to the core, the differences being the habitation type and the smaller burial sites. Reasons for this might be the lower population density in general and another geographical situation.

From [1.3]

Jastorf also expanded into the north, the west and to a lesser extent to the east in the 6th and 5th centuries BC. On the eastern periphery, Jastorf blended into the Pomeranian and later Przeworsk cultures, while on the northern periphery it did so into the Nordic iron age (c. [1.4], see the part about Scandinavia). The western periphery is somewhat different, as a drift away from Jastorf can be observed there with the appearance of La Tène influence. Some, therefore, place it among the cultures of the Contact Zone (see the part about NW-Germany and the Netherlands) during the period of our interest.

In the 2nd century BC, a migration from the east to the land of the southern periphery appears to have happened (c. [1.5]). Burials and settlements of the Przeworsk culture appear around the Saale river and to a lesser extent the Unstrut river (so-called Saale-Unstrut group), both regions with a lower population density. The number of migrants was relatively small, however, and around the time of Caesar’s campaigns these people leave again. Although the Przeworsk pottery had a much further extending distribution area, only one quarter of this pottery was used for Przeworsk burials and had stylistic influences from Poland. The other three quarters were a stylistic mix between Jastorf and Przeworsk. This phenomenon also spread further west to Hesse, where some Przeworsk settlements and burials were found in lowly populated peripheral areas; there are, however, no finds in or around the La Tène oppida or any other larger settlements.

blue: Przeworsk settlements, yellow: Przeworsk cemetries, black squares: Preworsk burials on Jastorf cemetries, black dots: Przeworsk pottery or pottery inspired by it. From [1.5].

Tribes of the Regions:

Discussion

There are only a few changes necessary here. The addition of the Hermunduri and Quadi should be made, and together with the Marcomanni they could represent southern periphery, as all three migrated in the late 1st century BC fitting with the archaeological evidence. Although there are areas of sparser population, there are Jastorf findings up to the border of the La Tène culture (in this case the Naumburger culture, which also had some Jastorf people mixing with them).

The Fosi should be far smaller, as they were first mentioned only by Tacitus as a ‘vassal’ of the Cheruskians. The Langobardians should also be smaller (as indicated by Tacitus) and located west of the Elbe, as they moved to the east during the Germanic campaigns. As the Chaucians should be more western (see section about NW Germany), adding the Suardones can fill the vacuum; they are related to Schwerin but otherwise there’s no way to link them to another positions. The Reudigni would take the position of the Chaucians then (as they cannot be linked to a region, too). The border of both would be extended further to the north to make them more in-line with the sub-groupings of Jastorf (see figure "Divisions of Jastorf").

Tacitus also mentions the Nuithones, while Ptolemaios mentions Teutons for the area where I put the Nuithones. It could be an error by Ptolemaios or by Tacitus (or both), however Tacitus seems more reliable and the Teutons are already located on the Cimbric peninsula (I’d also say that Teutones would’ve been more famously mentioned than that). One can also fit their sites to another sub-group of Jastorf.

It is hard to assess which tribe (or whether they just joined an existing one) is related to the Saale-Unstrut group, but as there were only few people related to these the tribe they might have belonged to was quite small. The Naristi or Buri would be two candidates; the latter because they were said to speak Suebian (Tacitus) but were part of the Lugian confederation (Ptolemaios).

North-Western Germany, the Netherlands and the Contact Zone between Jastorf and La Tène

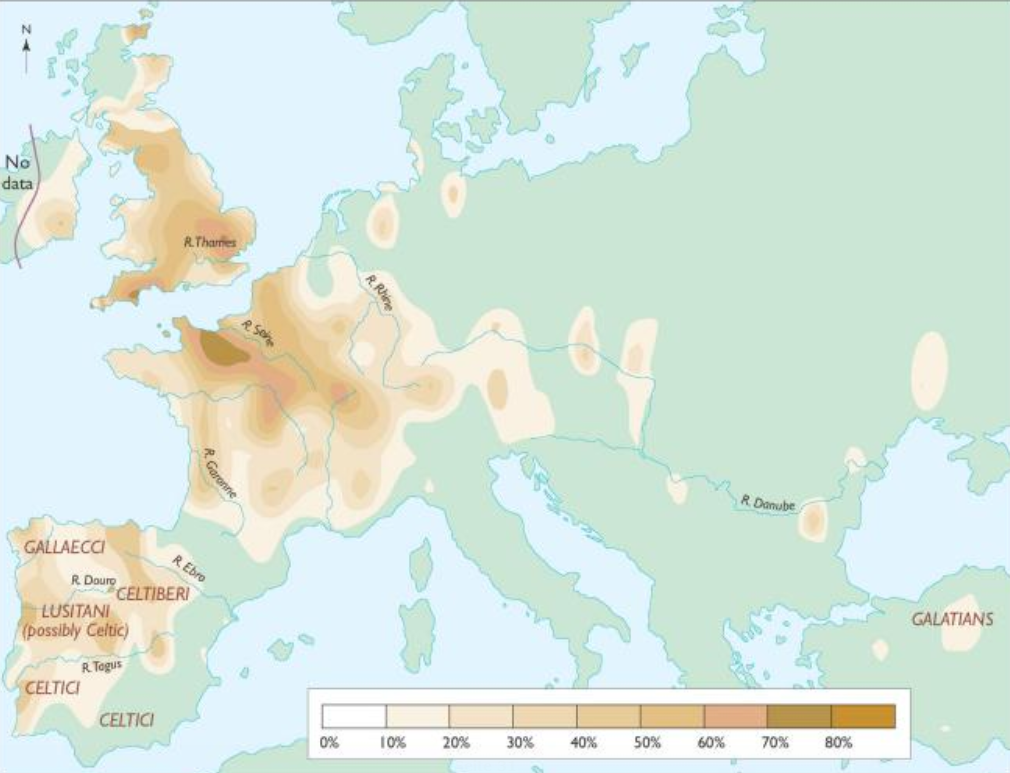

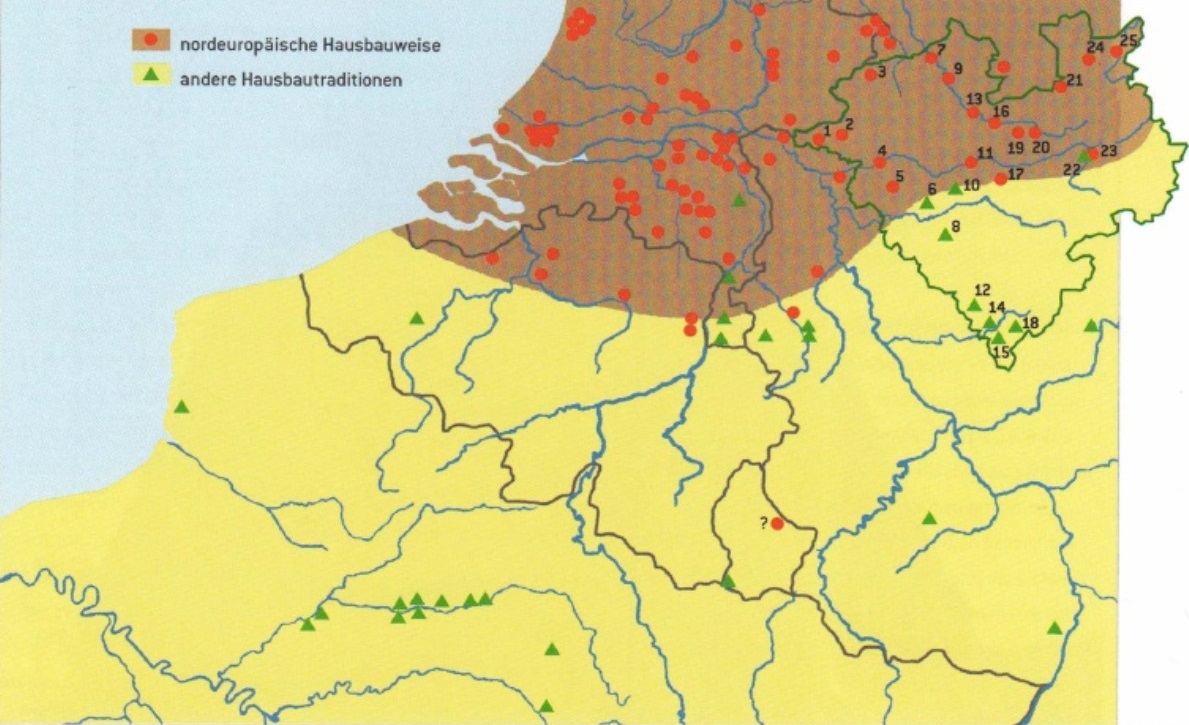

As I’ve already mentioned, the archaeology of north-western Germany is a ‘mess’ compared to the quite clear cut Jastorf concept. There aren’t any globally applicable characteristics. The Harpstedt-Nienburger group concept tried basing it on singular objects that were more widespread (mostly throughout the mid-Iron Age), however these haven’t been found in all areas of this zone, leading again to zones with no affiliation. Some, thus, extend the Harpstedt-Nienburger group to encompass all of north-western Germany and the Netherlands, but then the term becomes quite misleading. A more appropriate term is ‘Contact Zone between Jastorf and La Tène’ for this period. In fact, this is one of the few connecting elements; the influence of both well-defined cultures degrades the further away an area from the core of the respective cultures is (c. [2.1]).

According to Barry Cunliffe [2.2], the best way to look at the Europe of that time, is to see it as a series of peripheries of decreasing social and economic complexity the further one moved away from the Mediterranean. What can be deduced of the Germanic society of the 1st century BC and AD from Caesar and Tacitus gives the impression of communities differing little from the Celts of the fourth and third centuries BC. In other words, degree of social complexity cannot be taken as a distinguishing factor between Celt and German. This model neatly ties in with the Contact Zone, as generally speaking the ‘civilisation value’ (in-game term) decreases the further away from La Tène and the closer one to Jastorf is in this zone.

1) urn burial 2) bone bed 3) "Brandschüttungsgrab" - pyre burial with urn 4) "Brandgrubengrab" - pyre burial without urn. From [2.5].

From around 330 BC, the Late Iron Age or Celtic iron age started in the continental area [2.3], while the start is put to 300 or 270 BC for the Netherlands [2.4]. In the Late Iron Age, the burial customs changed through the adoption of Celtic-inspired ones (all four of figure "cremation types", c. [2.5]), new jewellery and art styles were introduced, and new technologies were adopted. The changes varied from region to region, creating a tremendous puzzle (c. [2.1] and [2.6]). Other phenomena tied to the burial rites are the sporadic appearance of Celtic influenced wagon burials (c. [2.7] and [2.8]) and highly furnished barrows mostly in Drenthe (e.g. Fluitenberg, c. [2.9]), possibly indicating the growth of elites from time to time in contrast to (east German) Jastorf, where burials were very egalitarian until the late 1st century BC. The Late Iron Age ends with a transition period (50 BC to 12 BC/16 AD), which was caused through the disruption created by Caesar’s Bello Gallico. The interaction between the people of the Contact Zone and Jastorf, then started to increase until Drusus started his campaign, causing another disruption. The first few situlae from the east were imported and adapted in this period [2.10].

From [2.6].

From [1.6]

Dark green: early form, lime: late form. From [2.10].

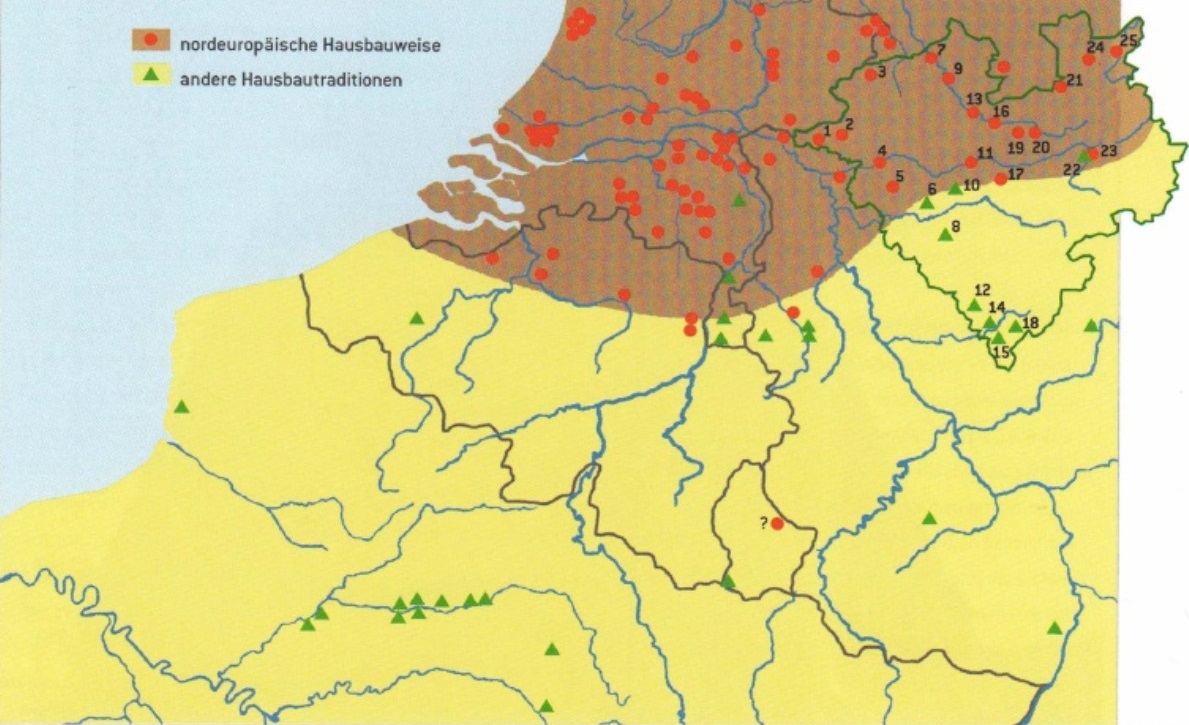

There were three main habitation types in the Contact Zone. Firstly, along the Dutch and the North Sea coastline, terps (dwelling mounds) were used with a quite high population density of 15 inhabitants per km².The Dutch terp region was colonised by inhabitants of the interior parts of the Netherlands in the 6th century BC, whereas the East Frisian terp region was settled in the 1st century BC by the people of the Wildeshausen Geest (c. [2.11] – [2.14]). In the terp region, excarnation by dogs and inhumation are rarely practiced, while cremation is assumed to have made up most burials [2.15]. Secondly, byre dwellings occurred in areas with sandy soil, where livestock was needed to fertilise the land (see figure, c. [2.16]). Lastly, in more arable regions (e.g. southern Westfalia), farmsteads specialised in either animal husbandry or agriculture appeared instead. Surpluses were sometimes produced which were stored in pits shaped like truncated cones [2.17]; this contrasts with Jastorf and the other two types. Additionally, some defensive sites were built (or re-built from older sites dating to the 6th and 5th centuries BC) in the more mountainous zones in the 4th - 3rd century BC, indicating some form of social organisation [2.18].

Byre dwelling

Farmstead. From [2.1].

red dots: byre dwellings, green triangles: other types. From [2.16].

I will now list a few groups of this area outside of the aforementioned Frisian Terp group and their characteristics, but they did not necessarily correspond to tribes, because of at times only small differences (c. [2.1] and [2.6]):

From [2.1].

Excursus: La Tène in Central Germany

Tribes:

Again, some tribes mentioned for this region will be presented. Etymologies for some will be given:

Discussion

One might now ask what we can deduce from all of this. Firstly, we have local developments which were influenced by foreign people but were unique, so that a large-scale migration bringing a ‘finished’ culture with them can be ruled out. From this the question arises how the majority of these people (or at least their elite) ended up speaking a Germanic language but still seemingly had a strong Celtic influence, because the tribal names are oft Germanised forms of Celtic words or words that could be interpreted as either. One could speculate that the people were slowly Germanised, i.e. that the number of Celtic speakers was higher in 300 BC and was lowered by assimilation over the next few centuries. This, however, has the problem that people of the same tribe would speak a different language and yet somehow needed to communicate with each other. Furthermore, the archaeology doesn’t show any hints towards such a process, while the Celtic world was even more influential in the Contact Zone in the Late Iron Age. This Celtic influence in the tribal names is something that speaks against a migration from far away (e.g. Scandinavia), as the name had to evolve at a place with a strong Celtic influence. Some even argue that the North-Sea Germanic pecularities were introduced from Brythonic [2.27], but what is certain that the people of that area had trade relationships with south-eastern England in the late Hallstatt - early La Tène period, facilitating language exchanges (see figure "Trade Routes and Atlantic Facade").

From [2.1].

In my opinion, the most conclusive argument on how to resolve this is a bilingual area or a Germanic and/or Celtic accent that was heavily influenced by the other. One shouldn’t forget that, before the ‘invention’ of modern standardised languages, people along border territories were still able to communicate with each other either by their accents fading into each other or bilingualism. E.g. Celtic in 300 BC had branched out into several groups, and someone from Ireland would’ve had troubles communicating with someone from Pannonia (c. e.g. [2.2]).

This still leaves the problem how to translate something like this into the game. The best way I came up with is to split basically along the La Tène line, i.e. Istvaeones, Ingvaeones, Germani and Cisrhenani as Germanics and Treverian (or perhaps rename it to Germano-Celtic) and (southern) Belgae as Celts. These groups would then need a decision to change their cultural affiliation, as the Contact Zone might have joined La Tène if it hadn’t been for Caesar’s Bello Gallico and some Celtic rebels went to Germania after their revolt against the Romans failed. For the Germanics, the condition could be tied to having a comparable civilisation and centralisation value like a Celtic neighbour, whereas the Celts could ‘degrade’ to Germanics by doing the reverse and reducing their civilisation value and centralisation. This should certainly hamper stability and take some time, i.e. a first larger bump and then a slow assimilation of the rest to the new culture and religion. A Celt becoming a German being less attractive is something that is also historical.

Based on the uniqueness of the Frisian Terp group, there’s no way around putting the Frisii there; a ‘migration’ from the west after 300 BC is contradicting archaeological evidence. The Chauci would then take the current position of the Frisians. Further to the south, the Bructeri would border the Chamavi and the Angrivarii, as the latter expelled the Bructeri in the 1st century AD. The Ampsivarii would inhabit a small area around the Ems river, as that is from where their name derives from. The Sugambri follow below the Bructeri and are bordered by the Usipetes and Tencteri to the west, because both those tribes were expelled by the Suebians and later on admitted by the Sugambrians during the Bello Gallico. This indicates that they bordered the Suebians and had prior contacts with the Sugambrians, but there’s no absolute certainty from where they came. Lastly, the Chatti together with their vassal the Batavi (c. description by Tacitus) get the rest. I’d say that the Batavi’s inclusion is warranted because of their fame.

Special thanks to @Wavey for squashing some textual errors.

Today @vanin and I are going to explore the ‘filthy barbarians’ of the cold north – also known as Germanics - with you. We decided to do this to write an overview of the ‘Germanic’ archaeology and written sources of the Pre-Roman Iron Age (pRIA) for all who are interested, to propose several improvements for Imperator’s map and to counter some misconceptions that have been circulating. Among these are this map of the pRIA, in which the House Urns culture, which vanished between 525 and 450 BC and wasn't a contemporary of the Oksywie culture, and a large gap between the Harpstedt-Nienburger and La Tène cultures is shown, although there were many findings in the latter region. The Harpstedt-Nienburger concept is also not very appropriate for the period of our interest, as it describes some inhomogeneous groups sharing two pottery styles of the middle pRIA (570 to 330 BC). Additionally, some space will be devoted to discussing the myths that are still overvalued by some in comparison to archaeological evidence.

To summarise this quite long thread:

Starting with what Germanics actually were in the view of ancient authors and our more modern interpretation, Germanics are introduced as speaking a Germanic language because there was not one but there were many ‘Germanic’ archaeological cultures; bilingualism is discussed in this regard, too. This is followed by the archaeology of four regions. Firstly, the north-east of Germany with the Jastorf culture, its peripheries and its expansion to the south, which lead to the replacement of the House Urns culture, are discussed. This is followed by the north-west of Germany and the Netherlands, which both built a quite inhomogeneous Contact Zone between the La Tène and Jastorf cultures. This zone was more advanced than Jastorf, and a strong Celtic influence on the region’s tribal names might indicate bilingualism there.

In the second part written by @vanin , the archaeology of Poland and Scandinavia is going to outlined. The section on Poland is centred around the question of what evidence there is that Germanics lived in the area, as well as around the Celtic influence and appearance of Celtic religious practices. Thereafter, the Scandinavian part is made up of Jutland’s relation to the Jastorf culture and the remote character of the Scandinavian peninsula for the first half of Imperator’s time frame. An ansatz for a Swedish and Norwegian setup based on ancient sources is proposed, as overemphasizing the medieval accounts of Jordanes and the medieval names of particular Swedish and Norwegian regions leads to the wrong impression that the Vikings had been living on the Scandinavian peninsula since time immemorial.

The proposed setup would look like this:

Who was Germanic?

Inventing a culture is a deed not many can claim, but Caesar did exactly this in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico. There he simply called everyone from east of the Rhine Germanic opposed to the Gauls west of the Rhine. When he describes the 'lifestyle' of these tribes, differences between his so-called Germans become apparent, e.g. he states that the Suebians lived only in small villages whereas the Ubians are described to have lived in oppida.

Caesar's definition of culture based on geography is far from our modern culture term, however. We consider customs, behaviour and language indicative for a somewhat abstract culture. Neither of these are easily accessible to us, as we lack self-written sources and we certainly do not know how many and who spoke which or what language. Archaeology can somewhat help us with customs, but we only see the unanimated used objects and not what was done with them.

Therefore, for the purposes of this text, a Germanic will be considered to be a person who spoke a Germanic language. This may sound straightforward, but not so, for many people in the past may have spoken more than a single language, one in their immediate community and another for communication with more distant neighbours. If Germanic was the language of the family, then they might be reasonably regarded as Germanic, but if they used Germanic only as a lingua franca to facilitate external interactions, then should they be called Germanic? Probably not. Otherwise in transitional regions, there might have been proper bi-lingual areas where two languages (or even more) were used on a daily basis. What were they? Probably calling them Celto-Germanic, Germano-Celtic or there like might be an appropriate way. As they need to be part of one culture group for in-game purposes, we can look to archaeology and determine whether or not they were closer to one group or to another one.

Short overview over the early Germanic language

Germanic is a part of the Indo-European (IE) language family. Pre-Germanic developed from IE and became later proto-Germanic, which is mostly placed around the middle of the first millennium BC (in the Kurgan and Anatolian hypotheses). This development was gradual, so it gives only a rough date when significant change happened. The first attested Germanic word(s) date(s) to the late 3rd century BC; they are the names of the Sciri and Bastarnae tribe. For the latter the name origin is still a matter of dispute, while it is less so for the Sciri.

In 300 BC, proto-Germanic was still spoken and underwent some more changes before it became Germanic. Two important ones are described by Grimm’s law and Verner’s law. Grimm’s law is dated to the early first century BC, as the Cimbri’s name would’ve been Chimbri if it had spread before that date (at least for the area from where they originated). It’s first attested when the Cheruski and a bit later the Chatti tribes are mentioned. Verner’s law is sometimes dated to after Grimm’s law had already become the norm, but others argue that it’d be too much change in a short period of time, so that they suggest Verner’s law occurred before Grimm’s law.

There are many theories about how the Germanic language spread, but only DNA studies in the next couple of years will probably give us enough hints to reconstruct its history. We only know in which regions Germanic constituted the majority’s (at least of the elite) primary language from the first century BC onwards based on the name evidence.

In 300 BC, proto-Germanic was still spoken and underwent some more changes before it became Germanic. Two important ones are described by Grimm’s law and Verner’s law. Grimm’s law is dated to the early first century BC, as the Cimbri’s name would’ve been Chimbri if it had spread before that date (at least for the area from where they originated). It’s first attested when the Cheruski and a bit later the Chatti tribes are mentioned. Verner’s law is sometimes dated to after Grimm’s law had already become the norm, but others argue that it’d be too much change in a short period of time, so that they suggest Verner’s law occurred before Grimm’s law.

There are many theories about how the Germanic language spread, but only DNA studies in the next couple of years will probably give us enough hints to reconstruct its history. We only know in which regions Germanic constituted the majority’s (at least of the elite) primary language from the first century BC onwards based on the name evidence.

Archaeology of ‘Germanics’ and Germanic Tribes

For a long time, there was the assumption that a unified archaeological culture would indicate a unified culture and language of these people, however in modern times this is no longer thought to be true. Transition zones are included in modern models.

When it comes to who lived there then we only know about people living in these areas from ancient sources. The first mentions of Germanic tribes dates to the first century BC, when Caesar campaigned in Gaul. As a huge part of the map would be uninhabited if one would only use certain information, PDX chose to extrapolate from the first mention back to our start date. Archaeology is a good indicator to track down any major population shifts or migrations from or to an area. What one shouldn’t forget is that such a fickle society also means that names could change, but they are the only names we have so it’s not that wrong to use a possibly later name for the same people (from whom that later name also emerged). This is however no longer possible when one has names like Heruli who seem to emerge from a mix of Sarmatian, continental Germanic (Goths) and Jutish people (possibly also others). In such a situation, using the name would lead to the wrong impression of a long-standing continuity that did not exist.

North-Eastern Germany and the Jastorf Culture

Since its introduction over a hundred years ago, the Jastorf culture has become a well-accepted concept. The Jastorf culture lasted from around 600 BC up to Christ’s birth and developed from the local Bronze Age culture with settlements and graveyards were continuing to be used throughout the transition. Nowadays, it is divided into two periods I (divided into a, b, c, d) and II (divided into a, b, c, d) of which the latter is characterised by southern influence from the La Tène culture; there was still influence from the Celtic south in the first phase, however. A century ago the second phase was divided in two and named Ripdorf (300 BC to 150 BC) and Seedorf (150 BC to 1 AD), but this would imply a major cultural shift that didn’t occur. La Tène culture mostly impacted the pottery, some tools and some jewellery (see [1.1]), while other cultural elements such as burial rites did not change in the long run.

Jastorf’s characteristics are (apart from its pottery, tools and jeweller), cremation followed by burial the urn with the remnants in a simple earthen pit. During the early phase of La Tène influence other burial rites appeared, but vanished soon afterwards, leaving only the ‘ordinary’ Jastorf burial practice. Because all burials are the same until the 1st century BC, Jastorf is often considered to be a very egalitarian society with no clear elite. The burial sites are often very large in the core territory (see section about subdivision), e.g. Mühlen-Eichsen is the largest one with about 5000 burials (c. [1.2]). In its southern periphery (see section about subdivision) the cemeteries are smaller with Chörau being the exception. The Jastorf people lived in three-aisled byre-dwellings in its core territory, whereas the people lived in pit-houses in the southern periphery.

From [2.1]

There are some concepts about how to divide the Jastorf culture spatially (see figure "Divisions of Jastorf", [1.3]), but its core territory is north-eastern Germany, from which it expanded westwards, southwards and into Jutland. The southern periphery came into being at the end of the 6th century BC and replaced the preceding House-Urns culture. It is nearly identical to the core, the differences being the habitation type and the smaller burial sites. Reasons for this might be the lower population density in general and another geographical situation.

From [1.3]

Jastorf also expanded into the north, the west and to a lesser extent to the east in the 6th and 5th centuries BC. On the eastern periphery, Jastorf blended into the Pomeranian and later Przeworsk cultures, while on the northern periphery it did so into the Nordic iron age (c. [1.4], see the part about Scandinavia). The western periphery is somewhat different, as a drift away from Jastorf can be observed there with the appearance of La Tène influence. Some, therefore, place it among the cultures of the Contact Zone (see the part about NW-Germany and the Netherlands) during the period of our interest.

In the 2nd century BC, a migration from the east to the land of the southern periphery appears to have happened (c. [1.5]). Burials and settlements of the Przeworsk culture appear around the Saale river and to a lesser extent the Unstrut river (so-called Saale-Unstrut group), both regions with a lower population density. The number of migrants was relatively small, however, and around the time of Caesar’s campaigns these people leave again. Although the Przeworsk pottery had a much further extending distribution area, only one quarter of this pottery was used for Przeworsk burials and had stylistic influences from Poland. The other three quarters were a stylistic mix between Jastorf and Przeworsk. This phenomenon also spread further west to Hesse, where some Przeworsk settlements and burials were found in lowly populated peripheral areas; there are, however, no finds in or around the La Tène oppida or any other larger settlements.

blue: Przeworsk settlements, yellow: Przeworsk cemetries, black squares: Preworsk burials on Jastorf cemetries, black dots: Przeworsk pottery or pottery inspired by it. From [1.5].

Tribes of the Regions:

In the following, some tribes of the region together with their first mention are listed. Caesar’s Commentarii are dated to 58 BC to 51 BC, the Germanic campaigns are dated to 12 BC to 14 AD, Plinius left Germania before 59 AD and Tacitus’s Germania is dated to around 100 AD.

- Semnones (Ger. Camp., possibly even Caesar as ‘Suebi’)

- Langobardi (Ger. Camp.)

- Cheruski (Caesar)

- Fosi (Tacitus)

- Varini (Plinius)

- Hermunduri (Ger. Camp.)

- Marcomanni (Caesar)

- Quadi (Ger. Camp., their name is related to the north German word for bad, ‘quade’ or ‘quaad’)

- Nuithones (Tacitus)

- Suardones (Tacitus)

- Reudigni (Tacitus)

Discussion

There are only a few changes necessary here. The addition of the Hermunduri and Quadi should be made, and together with the Marcomanni they could represent southern periphery, as all three migrated in the late 1st century BC fitting with the archaeological evidence. Although there are areas of sparser population, there are Jastorf findings up to the border of the La Tène culture (in this case the Naumburger culture, which also had some Jastorf people mixing with them).

The Fosi should be far smaller, as they were first mentioned only by Tacitus as a ‘vassal’ of the Cheruskians. The Langobardians should also be smaller (as indicated by Tacitus) and located west of the Elbe, as they moved to the east during the Germanic campaigns. As the Chaucians should be more western (see section about NW Germany), adding the Suardones can fill the vacuum; they are related to Schwerin but otherwise there’s no way to link them to another positions. The Reudigni would take the position of the Chaucians then (as they cannot be linked to a region, too). The border of both would be extended further to the north to make them more in-line with the sub-groupings of Jastorf (see figure "Divisions of Jastorf").

Tacitus also mentions the Nuithones, while Ptolemaios mentions Teutons for the area where I put the Nuithones. It could be an error by Ptolemaios or by Tacitus (or both), however Tacitus seems more reliable and the Teutons are already located on the Cimbric peninsula (I’d also say that Teutones would’ve been more famously mentioned than that). One can also fit their sites to another sub-group of Jastorf.

It is hard to assess which tribe (or whether they just joined an existing one) is related to the Saale-Unstrut group, but as there were only few people related to these the tribe they might have belonged to was quite small. The Naristi or Buri would be two candidates; the latter because they were said to speak Suebian (Tacitus) but were part of the Lugian confederation (Ptolemaios).

1) Egon Heinz, Die Keramik der Jastorf-Kultur, 2015

2) Peter Ettel, Das Gräberfeld von Mühlen Eichsen, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Zum Stand der Ausgrabung, Aufarbeitung und Auswertung, 2014

3) Frank Nikulka, Zur Regionalisierung der Jastorf-Kultur Theoretische und methodische Grundlagen, 2014

4) Jes Martens, Jastorf and Jutland (On the northern extent of the so-called Jastorf Culture), 2014

5) Michael Meyer, Frühe "Germanen" in Hessen, 2012

6) Vladimír Salač, Zwei Beispiele des Beharrungsvermögens in den Eisenzeitinterpretationen: Die Oppida und die Markomannen, 2013

7) Jochen Brandt, Martin Schönfelder, Die Latènisierung der Jastorfkultur. Kulturkontakt als Folge germanischer Raum-Zeit-Konzeptionen, 2010

8) Harald Meller, Glutgeboren. Mittelbronzezeit bis Eisenzeit, 2015

2) Peter Ettel, Das Gräberfeld von Mühlen Eichsen, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Zum Stand der Ausgrabung, Aufarbeitung und Auswertung, 2014

3) Frank Nikulka, Zur Regionalisierung der Jastorf-Kultur Theoretische und methodische Grundlagen, 2014

4) Jes Martens, Jastorf and Jutland (On the northern extent of the so-called Jastorf Culture), 2014

5) Michael Meyer, Frühe "Germanen" in Hessen, 2012

6) Vladimír Salač, Zwei Beispiele des Beharrungsvermögens in den Eisenzeitinterpretationen: Die Oppida und die Markomannen, 2013

7) Jochen Brandt, Martin Schönfelder, Die Latènisierung der Jastorfkultur. Kulturkontakt als Folge germanischer Raum-Zeit-Konzeptionen, 2010

8) Harald Meller, Glutgeboren. Mittelbronzezeit bis Eisenzeit, 2015

North-Western Germany, the Netherlands and the Contact Zone between Jastorf and La Tène

As I’ve already mentioned, the archaeology of north-western Germany is a ‘mess’ compared to the quite clear cut Jastorf concept. There aren’t any globally applicable characteristics. The Harpstedt-Nienburger group concept tried basing it on singular objects that were more widespread (mostly throughout the mid-Iron Age), however these haven’t been found in all areas of this zone, leading again to zones with no affiliation. Some, thus, extend the Harpstedt-Nienburger group to encompass all of north-western Germany and the Netherlands, but then the term becomes quite misleading. A more appropriate term is ‘Contact Zone between Jastorf and La Tène’ for this period. In fact, this is one of the few connecting elements; the influence of both well-defined cultures degrades the further away an area from the core of the respective cultures is (c. [2.1]).

According to Barry Cunliffe [2.2], the best way to look at the Europe of that time, is to see it as a series of peripheries of decreasing social and economic complexity the further one moved away from the Mediterranean. What can be deduced of the Germanic society of the 1st century BC and AD from Caesar and Tacitus gives the impression of communities differing little from the Celts of the fourth and third centuries BC. In other words, degree of social complexity cannot be taken as a distinguishing factor between Celt and German. This model neatly ties in with the Contact Zone, as generally speaking the ‘civilisation value’ (in-game term) decreases the further away from La Tène and the closer one to Jastorf is in this zone.

1) urn burial 2) bone bed 3) "Brandschüttungsgrab" - pyre burial with urn 4) "Brandgrubengrab" - pyre burial without urn. From [2.5].

From around 330 BC, the Late Iron Age or Celtic iron age started in the continental area [2.3], while the start is put to 300 or 270 BC for the Netherlands [2.4]. In the Late Iron Age, the burial customs changed through the adoption of Celtic-inspired ones (all four of figure "cremation types", c. [2.5]), new jewellery and art styles were introduced, and new technologies were adopted. The changes varied from region to region, creating a tremendous puzzle (c. [2.1] and [2.6]). Other phenomena tied to the burial rites are the sporadic appearance of Celtic influenced wagon burials (c. [2.7] and [2.8]) and highly furnished barrows mostly in Drenthe (e.g. Fluitenberg, c. [2.9]), possibly indicating the growth of elites from time to time in contrast to (east German) Jastorf, where burials were very egalitarian until the late 1st century BC. The Late Iron Age ends with a transition period (50 BC to 12 BC/16 AD), which was caused through the disruption created by Caesar’s Bello Gallico. The interaction between the people of the Contact Zone and Jastorf, then started to increase until Drusus started his campaign, causing another disruption. The first few situlae from the east were imported and adapted in this period [2.10].

From [2.6].

From [1.6]

Dark green: early form, lime: late form. From [2.10].

There were three main habitation types in the Contact Zone. Firstly, along the Dutch and the North Sea coastline, terps (dwelling mounds) were used with a quite high population density of 15 inhabitants per km².The Dutch terp region was colonised by inhabitants of the interior parts of the Netherlands in the 6th century BC, whereas the East Frisian terp region was settled in the 1st century BC by the people of the Wildeshausen Geest (c. [2.11] – [2.14]). In the terp region, excarnation by dogs and inhumation are rarely practiced, while cremation is assumed to have made up most burials [2.15]. Secondly, byre dwellings occurred in areas with sandy soil, where livestock was needed to fertilise the land (see figure, c. [2.16]). Lastly, in more arable regions (e.g. southern Westfalia), farmsteads specialised in either animal husbandry or agriculture appeared instead. Surpluses were sometimes produced which were stored in pits shaped like truncated cones [2.17]; this contrasts with Jastorf and the other two types. Additionally, some defensive sites were built (or re-built from older sites dating to the 6th and 5th centuries BC) in the more mountainous zones in the 4th - 3rd century BC, indicating some form of social organisation [2.18].

Byre dwelling

Farmstead. From [2.1].

red dots: byre dwellings, green triangles: other types. From [2.16].

I will now list a few groups of this area outside of the aforementioned Frisian Terp group and their characteristics, but they did not necessarily correspond to tribes, because of at times only small differences (c. [2.1] and [2.6]):

- Pestruper Group (1; Meppen-Oldenburg-Cloppenburg-Vechta): barrows above the funeral pyres, signet neck rings (E10), complex pendants (Wölpe), long hollow humps, bronze earrings (bat ear shape)

- Eilshausener Group (2; Osnabrück-Bielefeld-Minden-Nienburg): mostly Brandgrubengrab – rarely Brandschüttungsgrab, brooches (Babilonie), Jöllenbeck-Lahde fibulae, the trade hub Schnippenburg was there

- Three small Münsterlander groups/regions (3-5), which are still being investigated

- Pipinsburg group (6; Göttingen-Hildesheim-Braunschweig-Nordhausen): ornate pendants (Manching-Hadmersleben/Amelungsburg), vividly ornated needles, pottery produced with turntables, flat Scheiterhaufengräber

- Paderborner region (7): triangular loom weights, pit silos, usage of Hessian coins, no bangles, no pottery created with turntables

- Lippe-Ruhr region (8; area between those rives up to Dortmund): few imported bangles, Hessian coins in its east, nearly no loom weights and turntables

- Wupper-Siegengebirge region (10): hard-burnt simple pottery, only few bangles, nearly no coins but a huge treasure was found at Stieldorf, defensive sites (refuge castles) of Erdenburg, Rennenburg and Petersburg

- Betuwe-Ijssel region (9; Nijmegen-Wesel-Arnheim): many bangles (partially self-produced), triangular loom weights, many slings and their projectiles, vanishes after the Bello Gallico

- Maas-Rur region (11; Roermond-Grevenbroich-Venlo-Nieuwegein): many bangles (partially self-produced), no own coins but foreign ones used for trade

From [2.1].

Excursus: La Tène in Central Germany

Although the confluence between the Rhine and the Main was one of the ‘birthplaces’ of the La Tène culture, its spread towards the north was quite limited. The border is often drawn based on the extend of the oppida civilisation. The northern most are the Dünsberg, the Amöneburg, the Heidetränke, the Steinsburg and the Menosgada oppida. Even before these oppida were built, the vegetal and plastic style of La Tène art had spread there in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, and one can therefore rightfully place them among La Tène as its northern periphery. The most notable difference between central and southern Germany is the absence of Viereckschanzen in the north (the northernmost point of their extent is the Finsterlohr oppidum). Except for the Amöneburg, which is related to the Dünsberg, all of these are a centre of their respective region (Heidetränke and Dünsberg had a different coinage system).

Based on numismatic evidence and Caesar’s descriptions, the Ubii are nowadays linked to the Dünsberg oppidum. Their name can be either based on the Germanic uβjaz or the Celtic uϕor/uϕer for superior [2.20]. Some 2,500 personal names from inscriptions show an overwhelming majority of Latin and Greek names (77% for civilians and 79% for soldiers); Celtic (6% and 7%) follows next and is more popular with persons from an earlier time, and Germanic (4.5% and 4%) is on the third place [2.21]. Likewise, there are three other tribes described as geographically Germanic by Caesar. The Nemetes, the Tribocci and the Vangiones settled in Alsace at Caesar’s time. Although the latter has a clearly Germanic name, which means people of the field and contrasts with the Nemetes’ Celtic name (people of the forest) [2.22], only La Tène objects have been found in Alsace dating to that time. Based on settlement continuity for at least the 1st century BC and AD, Vangiones serving as auxiliaries for Caesar, Celtic names and Celtic gods being prevalent in that region as well as Worms bearing their name (Civitas Vangionum) the conclusion can be reached that the Vangiones were part of the La Tène cultural sphere [2.23]. Germanic objects only appeared when the Neckarsuebi were resettled to the area around modern Ladenburg, but by then the Celts had been heavily Romanised.

Viereckschanzen - ritual rectangular ditched enclosures (Both from [2.2]).

Based on numismatic evidence and Caesar’s descriptions, the Ubii are nowadays linked to the Dünsberg oppidum. Their name can be either based on the Germanic uβjaz or the Celtic uϕor/uϕer for superior [2.20]. Some 2,500 personal names from inscriptions show an overwhelming majority of Latin and Greek names (77% for civilians and 79% for soldiers); Celtic (6% and 7%) follows next and is more popular with persons from an earlier time, and Germanic (4.5% and 4%) is on the third place [2.21]. Likewise, there are three other tribes described as geographically Germanic by Caesar. The Nemetes, the Tribocci and the Vangiones settled in Alsace at Caesar’s time. Although the latter has a clearly Germanic name, which means people of the field and contrasts with the Nemetes’ Celtic name (people of the forest) [2.22], only La Tène objects have been found in Alsace dating to that time. Based on settlement continuity for at least the 1st century BC and AD, Vangiones serving as auxiliaries for Caesar, Celtic names and Celtic gods being prevalent in that region as well as Worms bearing their name (Civitas Vangionum) the conclusion can be reached that the Vangiones were part of the La Tène cultural sphere [2.23]. Germanic objects only appeared when the Neckarsuebi were resettled to the area around modern Ladenburg, but by then the Celts had been heavily Romanised.

Viereckschanzen - ritual rectangular ditched enclosures (Both from [2.2]).

Tribes:

Again, some tribes mentioned for this region will be presented. Etymologies for some will be given:

- Tencteri (Caesar): Celtic tencteroi or Germanic tenhteraz, both mean the unified people [2.24]

- Usipetes (Caesar): Celtic uxsipits, luminous in the heights [2.24]

- Chamavi (Ger. Camp.): Germanised (Grimm’s law) Celtic of comavus/camavus-, the powerful [2.22]

- Sugambri (Caesar): various versions of their name, gambri either Germanic (avid) or Celtic from camavus, su- is a Celtic prefix for good or strong

- Chatti (Caesar indirectly, Agrippa's 1st governorship of Gaul): Germanised (i.a. Grimm’s law) Celtic of cassis (Celtic god; c. Baiocasses) [2.25]

- Batavi (Caesar): Fully Celtic (batav-) for fighter or Germanic batawiz = better, Batavian place names are Celtic (Batavodurum, Lugdunum, Batavorum, Noviomagius), there are Celtic person names like Briganticus but also Germanic ones like Chariovalda [2.21]

- Bructeri (Ger. Camp.): Germanic like brook/broek or Celtic brogilo (district, wood, c. Allobrogae), ending Celtic or Germanic see Tencteri

- Angrivarii (Ger. Camp.)

- Ampsivarii (Ger. Camp.)

- Frisii (Ger. Camp.): Germanic for free (Old Germanic fri, Gothic freis) [2.22]

- Chauci (Ger. Camp.): Germanic like Old Germanic hôh = high or might be Germanised Celtic with Grimm’s law (c. Irish Cauci or Celtiberian Cauca – modern Coca) [2.26]

Discussion

One might now ask what we can deduce from all of this. Firstly, we have local developments which were influenced by foreign people but were unique, so that a large-scale migration bringing a ‘finished’ culture with them can be ruled out. From this the question arises how the majority of these people (or at least their elite) ended up speaking a Germanic language but still seemingly had a strong Celtic influence, because the tribal names are oft Germanised forms of Celtic words or words that could be interpreted as either. One could speculate that the people were slowly Germanised, i.e. that the number of Celtic speakers was higher in 300 BC and was lowered by assimilation over the next few centuries. This, however, has the problem that people of the same tribe would speak a different language and yet somehow needed to communicate with each other. Furthermore, the archaeology doesn’t show any hints towards such a process, while the Celtic world was even more influential in the Contact Zone in the Late Iron Age. This Celtic influence in the tribal names is something that speaks against a migration from far away (e.g. Scandinavia), as the name had to evolve at a place with a strong Celtic influence. Some even argue that the North-Sea Germanic pecularities were introduced from Brythonic [2.27], but what is certain that the people of that area had trade relationships with south-eastern England in the late Hallstatt - early La Tène period, facilitating language exchanges (see figure "Trade Routes and Atlantic Facade").

From [2.1].

In my opinion, the most conclusive argument on how to resolve this is a bilingual area or a Germanic and/or Celtic accent that was heavily influenced by the other. One shouldn’t forget that, before the ‘invention’ of modern standardised languages, people along border territories were still able to communicate with each other either by their accents fading into each other or bilingualism. E.g. Celtic in 300 BC had branched out into several groups, and someone from Ireland would’ve had troubles communicating with someone from Pannonia (c. e.g. [2.2]).

This still leaves the problem how to translate something like this into the game. The best way I came up with is to split basically along the La Tène line, i.e. Istvaeones, Ingvaeones, Germani and Cisrhenani as Germanics and Treverian (or perhaps rename it to Germano-Celtic) and (southern) Belgae as Celts. These groups would then need a decision to change their cultural affiliation, as the Contact Zone might have joined La Tène if it hadn’t been for Caesar’s Bello Gallico and some Celtic rebels went to Germania after their revolt against the Romans failed. For the Germanics, the condition could be tied to having a comparable civilisation and centralisation value like a Celtic neighbour, whereas the Celts could ‘degrade’ to Germanics by doing the reverse and reducing their civilisation value and centralisation. This should certainly hamper stability and take some time, i.e. a first larger bump and then a slow assimilation of the rest to the new culture and religion. A Celt becoming a German being less attractive is something that is also historical.

Based on the uniqueness of the Frisian Terp group, there’s no way around putting the Frisii there; a ‘migration’ from the west after 300 BC is contradicting archaeological evidence. The Chauci would then take the current position of the Frisians. Further to the south, the Bructeri would border the Chamavi and the Angrivarii, as the latter expelled the Bructeri in the 1st century AD. The Ampsivarii would inhabit a small area around the Ems river, as that is from where their name derives from. The Sugambri follow below the Bructeri and are bordered by the Usipetes and Tencteri to the west, because both those tribes were expelled by the Suebians and later on admitted by the Sugambrians during the Bello Gallico. This indicates that they bordered the Suebians and had prior contacts with the Sugambrians, but there’s no absolute certainty from where they came. Lastly, the Chatti together with their vassal the Batavi (c. description by Tacitus) get the rest. I’d say that the Batavi’s inclusion is warranted because of their fame.

1. Bernhard Sicherl, Zur kulturellen Gliederung Westfalens in der späten Eisenzeit, 2015

2. Barry Cunliffe, The Ancient Celts, 2018

3. Jürgen Gaffrey et al., Von der "Guten alten Zeit" – Chronologie, 2015

4. Stijn Arnoldussen, Iron Age habitation patterns on the southern and northern Dutch Pleistocenecoversand soils: The process of settlement nucleation, 2010

5. Bernhard Sicherl et al., Spiegel der noch Lebenden, 2015

6. Bernhard Sicherl, Namenlose Stämme – Nordwestdeutschland am Vorabend der römischen Okkupation, 2009

7. Birte Reepen, Archäologische Untersuchungenzu eisenzeitlichen Wagengräbern im nordwestdeutschen Raum, 2011

8. Jürgen Gaffrey, Ein Wagengrab in Westerkappeln, 2015

9. Annet Nieuwhof et al., Von Reichen und Armen - Eliten im archäologische Befund/Over rijken en armen - elites in het archeologisch onderzoek, 2013

10. Bernhard Sicherl, Frühe Situlen im Westen, 2015

11. Annet Nieuwhof, Mans Schepers, Living on the Edge: Synanthropic Salt Marshes in the Coastal Areas of the Northern Netherlands from around 600 BC, 2016

12. Annet Nieuwhof et al., Leben mit dem Meer: Terpen, Wierden und Wurten/Leven met de zee: terpen, wierden en wurten, 2013

13. Annet Nieuwhof et al., De late prehistorie en protohistorie van Holoceen Noord-Nederland, 2009

14. Jan F. Kegler, Sonja König, Hohe Hügel, fester Grund? Wurten als Grundlage der dauerhaften Besiedlung der südlichen Nordseeküste., 2016

15. Annet Nieuwhof et al., Of dogs and man. Finds from the terp region of the northern Netherlands in the pre-Roman and Roman Iron Age

16. Stephan Deiters, Siedlungswesen, 2015

17. Bernhard Sicherl, Kegelstumpfgruben der Eisenzeit, 2015

18. Jens Schulze-Forster, Die Burgen der Mittelgebirgszone. Eisenzeitliche Fluchtburgen, befestigte Siedlungen, Zentralorte oder Kultplätze, 2009

19. Jens Schulze-Forster, Wie Keltisch ist der Dünsberg, 2013

20. Stefan Zimmer, 2006 Ubier, Sprachlich, 2006

21. Joh. Leo Weisgerber, Die Namen der Ubier, 1968

22. Norbert Wagner, Lemovii, Helvecones*, Batavi, Βατίνοι, Chamavi, Cherusci Stammesnamen zwischenGermanen und Kelten, 2015

23. Ralph Haussler, Worms und die Vangiones. Fakten und Fiktionen, 2007

24. Stefan Zimmer, Usipeten, Usipier und Tenkterer Sprachlich, 2006

25. Norbert Wagner, Lat.-germ. Chatti und ahd. Hessi Hessen, 2011

26. Dietz, Karlheinz, Chauci (in Der Neue Pauly), 2006

27. CoverJohn Hines, Nelleke IJssennagger, Frisians and Their North Sea Neighbours, 2017

2. Barry Cunliffe, The Ancient Celts, 2018

3. Jürgen Gaffrey et al., Von der "Guten alten Zeit" – Chronologie, 2015

4. Stijn Arnoldussen, Iron Age habitation patterns on the southern and northern Dutch Pleistocenecoversand soils: The process of settlement nucleation, 2010

5. Bernhard Sicherl et al., Spiegel der noch Lebenden, 2015

6. Bernhard Sicherl, Namenlose Stämme – Nordwestdeutschland am Vorabend der römischen Okkupation, 2009

7. Birte Reepen, Archäologische Untersuchungenzu eisenzeitlichen Wagengräbern im nordwestdeutschen Raum, 2011

8. Jürgen Gaffrey, Ein Wagengrab in Westerkappeln, 2015

9. Annet Nieuwhof et al., Von Reichen und Armen - Eliten im archäologische Befund/Over rijken en armen - elites in het archeologisch onderzoek, 2013

10. Bernhard Sicherl, Frühe Situlen im Westen, 2015

11. Annet Nieuwhof, Mans Schepers, Living on the Edge: Synanthropic Salt Marshes in the Coastal Areas of the Northern Netherlands from around 600 BC, 2016

12. Annet Nieuwhof et al., Leben mit dem Meer: Terpen, Wierden und Wurten/Leven met de zee: terpen, wierden en wurten, 2013

13. Annet Nieuwhof et al., De late prehistorie en protohistorie van Holoceen Noord-Nederland, 2009

14. Jan F. Kegler, Sonja König, Hohe Hügel, fester Grund? Wurten als Grundlage der dauerhaften Besiedlung der südlichen Nordseeküste., 2016

15. Annet Nieuwhof et al., Of dogs and man. Finds from the terp region of the northern Netherlands in the pre-Roman and Roman Iron Age

16. Stephan Deiters, Siedlungswesen, 2015

17. Bernhard Sicherl, Kegelstumpfgruben der Eisenzeit, 2015

18. Jens Schulze-Forster, Die Burgen der Mittelgebirgszone. Eisenzeitliche Fluchtburgen, befestigte Siedlungen, Zentralorte oder Kultplätze, 2009

19. Jens Schulze-Forster, Wie Keltisch ist der Dünsberg, 2013

20. Stefan Zimmer, 2006 Ubier, Sprachlich, 2006

21. Joh. Leo Weisgerber, Die Namen der Ubier, 1968

22. Norbert Wagner, Lemovii, Helvecones*, Batavi, Βατίνοι, Chamavi, Cherusci Stammesnamen zwischenGermanen und Kelten, 2015

23. Ralph Haussler, Worms und die Vangiones. Fakten und Fiktionen, 2007

24. Stefan Zimmer, Usipeten, Usipier und Tenkterer Sprachlich, 2006

25. Norbert Wagner, Lat.-germ. Chatti und ahd. Hessi Hessen, 2011

26. Dietz, Karlheinz, Chauci (in Der Neue Pauly), 2006

27. CoverJohn Hines, Nelleke IJssennagger, Frisians and Their North Sea Neighbours, 2017

Special thanks to @Wavey for squashing some textual errors.

Last edited:

- 3

- 1

![bell beaker yamnaya[1].jpg bell beaker yamnaya[1].jpg](https://forumcontent.paradoxplaza.com/public/451227/bell beaker yamnaya[1].jpg)