X. The Expansionism of Ephron the Younger

It was nary two months since the dust of the Achaean Civil War had settled when an Egyptian envoy delivered a declaration of war. To understand the import of the Achaean-Egyptian wars at that time, one should bear in mind that the Second Punic War was in its thirtieth year, having equally exhausted both sides’ strength but not their stubbornness, and that the Seleucid Empire had already become irrelevant on the world stage, useful only in checking Parthian expansion towards the Greek world. Egypt and the Achaean League were thus the two great powers, at liberty to reshape the map of the world around them, and they were once again in conflict.

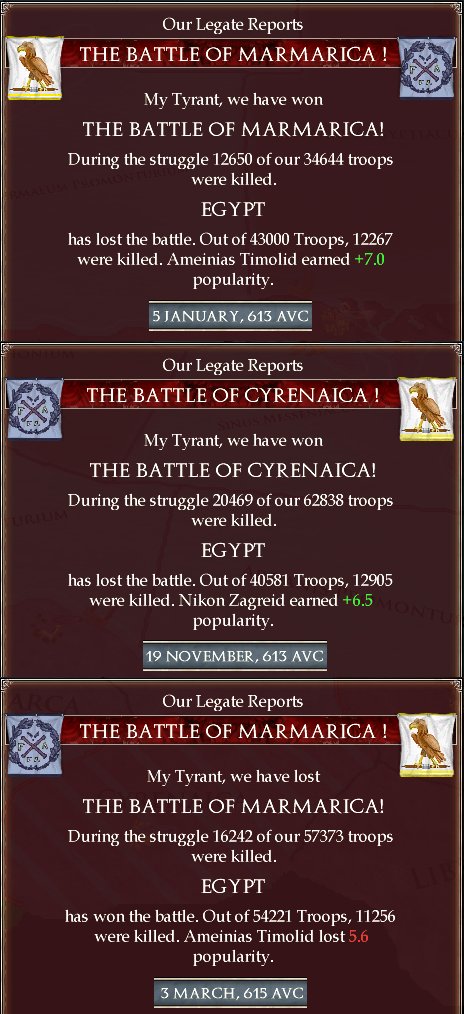

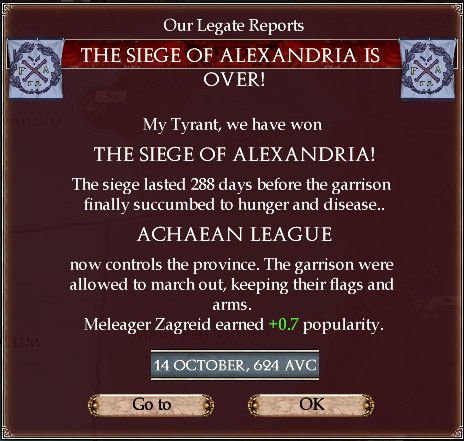

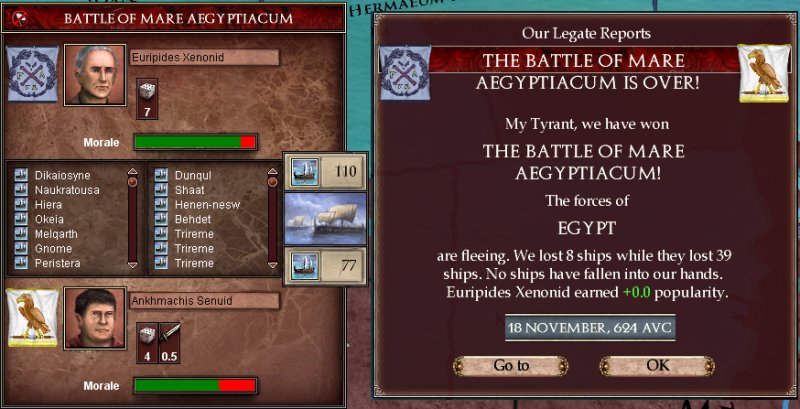

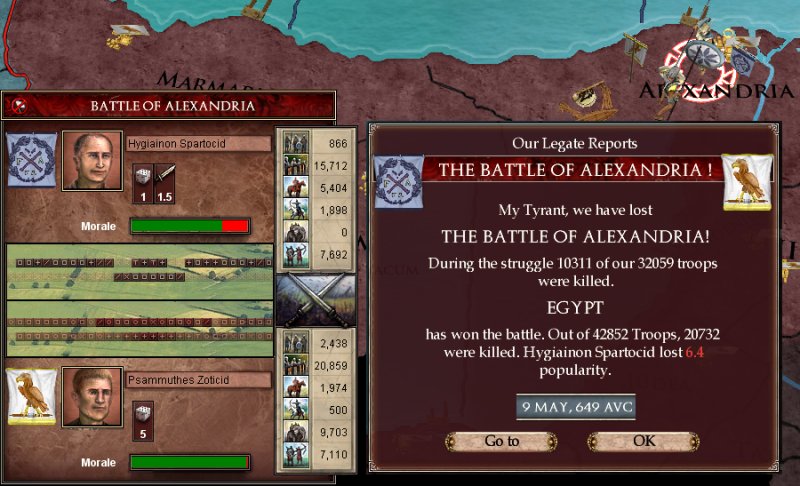

The war was fought in two theatres: Cyrene and Lydia. The Egyptian fleet had not recovered from its previous defeat, and so the Achaeans ruled the waves. However, that was of limited use with the Egyptian numerical superiority on land, apart from an easy occupation of Cyprus. The Achaean strategy was, of necessity, defensive, striking with concentration of force at the Egyptians whenever they were assaulting a city or whenever they appeared weak, and retreating when faced with overwhelming numbers. Even so, the difficulty of maintaining such a concentrated effort meant that many battles were fought that were far bloodier than the League could stomach; but on the whole, Egyptian casualties were far higher than the Achaean ones, and the Egyptian generals were vexed in their efforts to occupy Achaean lands for any protracted periods of time. So, after two years the Pharaoh agreed to an offer of gold for peace. The Achaean treasury being, as it so often was, overflowing, it was sensible policy to spend a small part of it to save untold thousands of lives from death on the battlefield with no prospect of territorial gain.

Meanwhile, the Roman republic was falling apart, with former client peoples declaring their independence and forming petty kingdoms or republics from the north of Gaul to the south of Italy. Carthage faced some splinter movements of its own, with Sardinia and parts of Africa having seceded from the Republic, but at least its armies had succeeded in taking the war to Gaul.

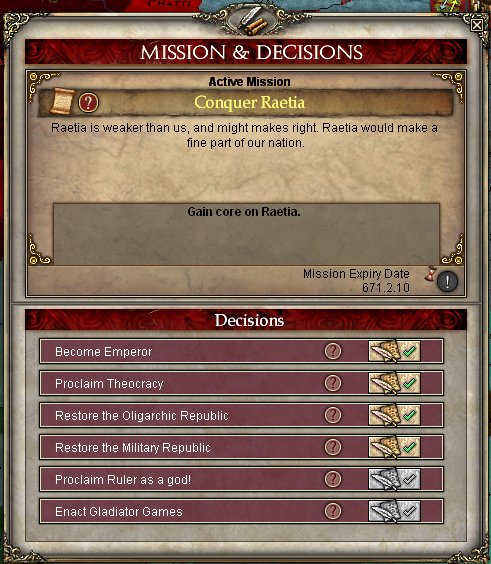

It was against that backdrop that Ephron decided to act aggressively and expand the Achaean League to Italy – for only by the strength provided by such territorial expansion could Egypt be countered in the long run. The Raetian tribes were the first to be invaded, since their colonies were in friction with the Achaean ones in Taurisci.

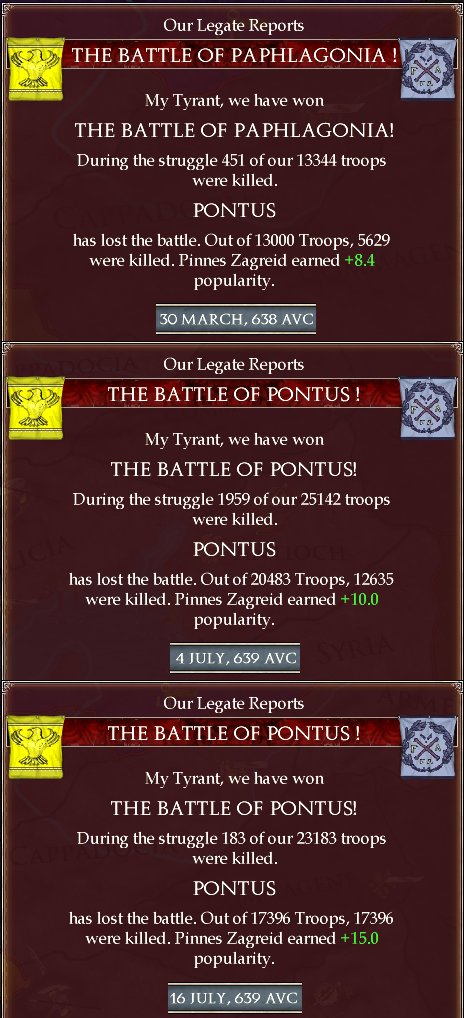

The war was short, and the Achaean League was content to take control over the colonies in question, rather than outright annex the Raetians. Such restraint was shown not so much out of fear for a Roman reaction, than because Rhodes called the League to help in a defensive war against Pontus. The latter had invaded Bithynia, which could not stand up to the might of the Pontic armies. But when the Achaean League joined the war, Pontus hastened to make truce with Bithynia, at a symbolic price.

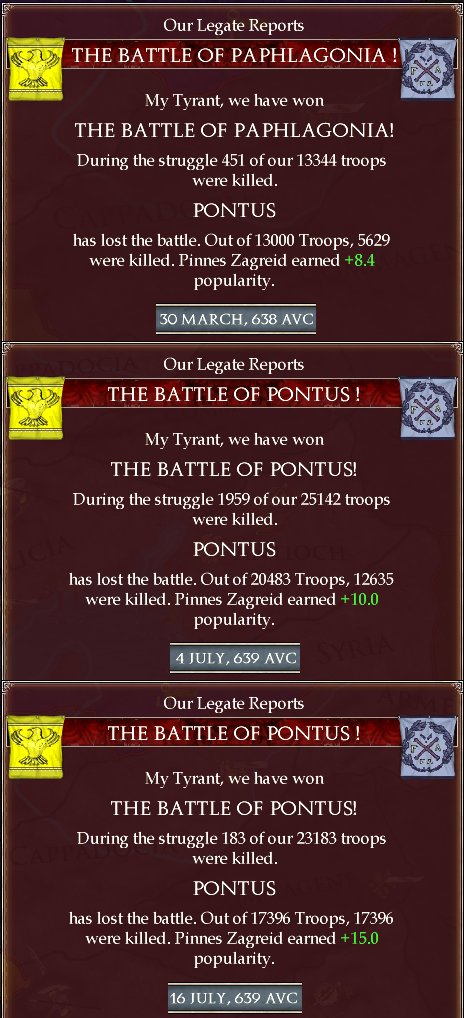

The Achaean League, Rhodes, Macedonia and the Seleucid Empire remained at war with Pontus. But the Seleucids were soon engulfed in a civil war, which made them unable to contribute to the allied effort.

The Achaean armies, marching through Bithynia, invaded Pontus and proved their clear superiority in a series of battles that culminated with the occupation of the Pontic capital.

By November 639AVC, the Pontic king had come to his senses and accepted the Achaean terms.

While war raged in distant Pontus, Achaean armies were also operating against the Seleucid rebels along the Danube and in Phrygia. They were successful enough that the League took control of Dardania before the rightful Seleucid king could snuff out the rebellion. But with war winding down in the east, Ephron once again turned his attention to the west. Syracuse, which had previously annexed Brutium, was experiencing some turmoil, with the rabble running loose in the city and the kingdom in chaos. It seemed like the only humane solution was to incorporate it into the Achaean League, and two armies were dispatched for that purpose. Soon after the League ended its participation in the Seleucid civil war, Syracuse was convinced by force of arms to join the great league of Greek cities.

Unfortunately, the stabilizing presence of Achaean troops was not enough to quell the citizens’ unrest right away; but the neighbouring Sicilian cities saw the possibility for improvement and voluntarily accepted Ephron’s rule.

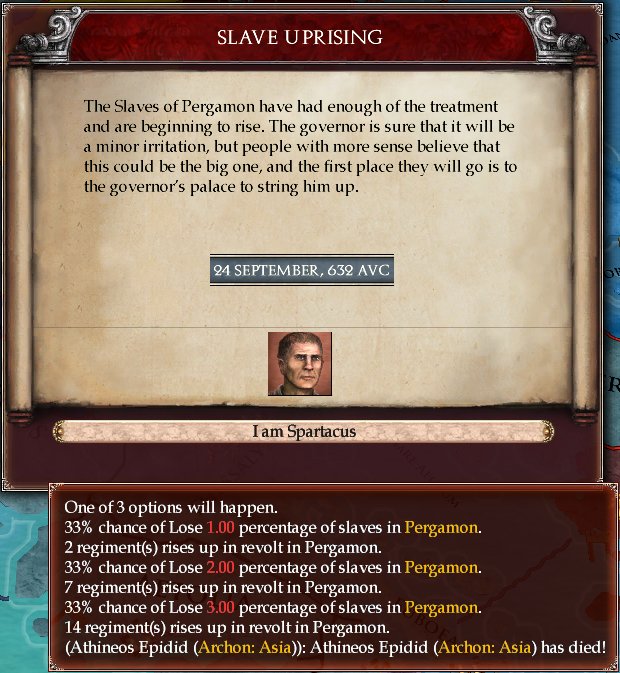

For the next two years, the League was at peace. The armies were given time to regroup and recruit, while trade was normalized. However, an unexpected source of friction would plant the seeds of future wars that would drastically reshape the map of Greece.

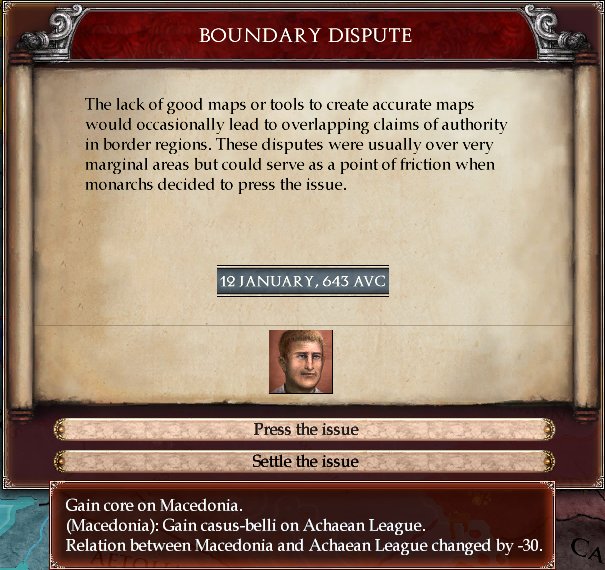

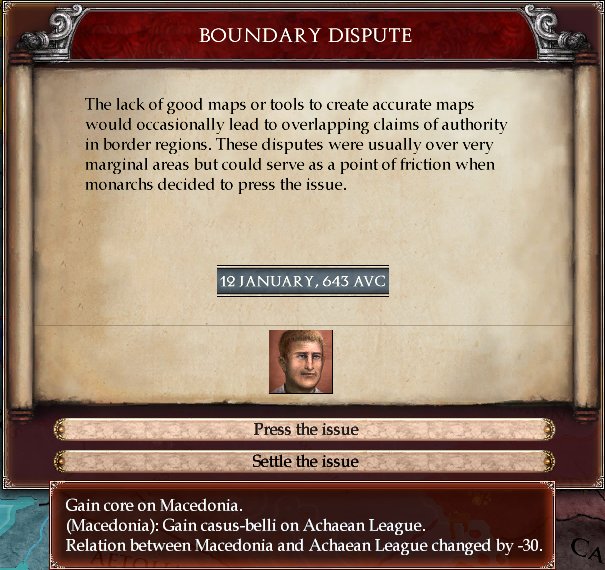

Ephron had been given a strong reason to interfere in Macedonian affairs. Moreover, Egypt was in the throes of a civil war, albeit a not very threatening one for the reigning pharaoh.

But before starting a war so close to home, Ephron was determined to complete his plan of expansion in the west. After the armies had been assembled, it only took a few months for the north Italian tribes to be brought under Achaean control. With the Magna Grecian League having actually occupied Rome and the Carthaginians gaining ground in Gaul, it seemed like the Roman Republic was done for. But the Romans were obstinate, even without their capital, and would not give the Carthaginians the satisfaction of gaining an inch of Roman land through a peace treaty.

Finally, on 30 October 644AVC, the Carthaginian senate had had enough. After 40 years of war, famine and anarchy, 40 years that saw both republics bleed continuously and lose lands to local uprisings, the Second Punic War was ended. Rome paid Carthage 10 gold.

Before the year was over, Ephron declared war on Macedonia, citing the boundary dispute as a casus belli. Bithynia and the Seleucid Empire took Macedonia’s side. Within a year, Achaean forces had almost complete control in Europe.

Macedonia was forced to cede two of its three provinces. Bithynia was forced to cede all its European territories, four provinces out of its five in total. The Seleucids were the last holdouts, when Egypt decided to intervene. However, it was too late to prevent the fall of Phrygia, after which the Seleucids agreed to cede their last Danubian colonies to the Achaean League. The final act of the Great Game was over.