III. 1836-1837: The Road to War

In the spring of 1836 Grand Duke Ludwig II, ready to push forward with his plans to expand Hesse-Darmstadt's power and influence, called together his Council of Advisers and laid out his plans for the coming year. He explained that in order to advance on the stage of German affairs the Grand Duchy would have to increase it's economic base and become an industrial power in the vein of Prussia. Of course, the Grand Duchy suffered from a lack of the resources necessary to achieve that goal and would always do so until it was able to acquire them by the only route open to it- force. To that end he charged them to assist him with two goals: the creation of a professional army for the Grand Duchy and the dramatic expansion of the militia from 10,000 men to 50,000. As if this wasn't enough to spring on them given the limited financial and material resources of the Grand Duchy, Ludwig also added that he would expect this new force to be ready to be "put to use" by next year.

Ludwig's plans immediately caused quite a bit of consternation amongst his advisers. This military buildup was not completely out of the question if given time, but in just one year? Where would the money come from? What good would it do to raise an army if you couldn't then afford to equip it properly or pay it, much less send it out on campaign?

The Crown Prince

In general any kind of protest to any plan of the Grand Duke's was rare as he, after all, could do whatever he wanted, but in this he did face some opposition. Surprisingly it came from his eldest son, the Crown Prince Ludwig. The Prince's concerns were mainly economic and he stated a fear that the state could not afford a military buildup and would end up bankrupted. He, having already known full well for some time his father's plans to use this new armed force in a war of aggression, also cautioned against what Hesse-Darmstadt's larger neighbors would think about the Grand Duchy trying to flex some military might. Hesse-Darmstadt, he said, was not meant to be an industrial or imperial power and it would be better for the nation to continue on as is.

While a great many among the council of advisers sided with the Crown Prince (I'll leave it up to the reader to decide if they actually agreed with him or simply knew on which side their bread would be buttered in the future), a roughly equal number enthusiastically supported the Grand Duke's plan. Interestingly enough, this faction was headed up by the Grand Duke's second son, Prince Karl. Karl, who had recently married into the Prussian royal family, had spent some time in the Prussian military and had seen first hand what a strong, professional army could do. A military-minded sort, he waved away the economic difficulties facing his father's plan and was nothing but enthusiastic about the prospect of turning Hesse-Darmstadt into a military powerhouse.

Prince Karl

The Grand Duke, naturally, was not impressed with the dissenting opinions and ordered his plan put into motion. That being done, all that was left to do was work out how it could be done. The Grand Duke did, however, bend slightly to economic necessity in that he agreed that the Grand Duchy could not support a full-time professional army larger than 10,000 men (he had originally hoped for 30,000). Immediately the call went out across Hesse-Darmstadt for volunteers for the Grand Duchy's first professional standing army.

By the end of the summer the full 10,000 had been recruited. No expense had been spared in their outfitting and training. The force that paraded by the Ducal Palace bore modern Prussian arms and equipment and had been drilled under the supervision of Prussian advisers. Prior to the parade the Grand Duke, attended by his sons Ludwig, Karl, and 13 year-old Alexander, had personally presented each of the army's 10 regiments with a standard that bore the Hessian royal lion over the national colors. Beneath the lion was the motto of the nation and now of it's army:

Gott, Ehre, Vaterland.

Headquarters of the new Royal Army and of the 1st Infantry Regiment

Hesse-Darmstadt now had a professional army to bolster it's militia force completing step one of the Grand Duke's plan. Next would be the increase of the militia which was to be renamed the National Guard. However, before any headway could be made in that area, the Grand Duke had to deal with a minor financial complication. The formation of the army had not been cheap. The Prussians had not given away the arms and equipment being carried by Hesse-Darmstadt's soldiers, and the advisers that had trained them certainly had not worked for free. Of course, a headquarters for the army had to be built as well as barracks for the 10 infantry regiments raised. Nor was this the end of the cost as, after all, these professional soldiers had to be fed and paid by the government. The end result was that the state's ledgers went into the red and money was pouring out of the treasury. The Council of Advisers warned the Grand Duke that a serious financial crisis would occur if something was not done.

The Grand Duke, not about to see his plans derailed before they had really begun, acted quickly and began looking for ways to right the financial situation. He could not raise taxes to overcome the difficulty as the people were already forced to give up 48% of their income as it was. Compelling them to give more would be ruinous to them, especially the poorer farmers. The only option as he saw it was to cut government spending, and he accordingly made adjustments which put the nation's ledgers back into the black and caused howls of protest from the University of Giessen's directer who suddenly found his funding dramatically cut.

The other major cut in spending made by the Grand Duke was to the constabulary force and it was this that would have the most lasting impact. A good many of Hesse-Darmstadt's constables (the predecessors of the national police force) had joined the army for it's better pay, so numbers were down when the cuts in funding came down. Little money was provided to bring the numbers back up and salaries were set at an all time low. As a result, what men could be gotten for the job were often not the most desirable candidates. Crime, which had never been a real problem in the Grand Duchy, began to rise in urban areas and would develop into a serious problem in coming years.

A lithograph printed in Darmstadt lampooning the new constables

With money going into the treasury once again instead of out, the Grand Duke was ready for the expansion of the National Guard. However, the economic situation once again began throwing up roadblocks. Treasury funds were low and the state was barely turning a profit. One member of the Council of Advisers stated (rather accurately) that it would take a decade or more for them to be able to afford the arming of an additional 40,000 guardsmen. The Grand Duke's plans ground to a halt in the face of this difficulty as no amount of consternation on his part could put money into the treasury.

The situation would remain thus until the early part of 1837 when an advancement in the technological field offered an opportunity to shore up the treasury. In February of that year, working off of a Prussian design, engineers at the University of Giessen designed a new steam locomotive engine. This might not have been anything of import as Hesse-Darmstadt had not one inch of railway, but the Grand Duke saw an opportunity and began shopping the new design around Europe. The design was eventually purchased by the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont and the Grand Duke found himself with more than enough funds to finally expand the National Guard.

Doing so was not easy, however. Hesse-Darmstadt had never had a National Guard force larger than 10,000 and indeed it often could not find even that many men willing to sign up. In order to guarantee that he got his 40,000 new recruits, Ludwig II issued a decree in late February that all of Hesse-Darmstadt's communities were required to provide men for the National Guard; the number being determined by the size of the community. Outrage rippled through the rural communities at this forced enlistment, especially once it became obvious that the majority of the forced recruitment would be done amongst the poor rural areas.

While Hesse-Darmstadt allowed no political freedoms and controlled information through a state-run press, it did allow for the people to come together in public gatherings. People across Hesse-Darmstadt's rural areas flocked now to such meetings in protest of the government's action. This is another area where the lack of a strong constabulary was felt. In the past, constables had gathered at these meetings both to intimidate and to report on what was said. There was little to no such supervision now and people began to speak out against the Grand Duke's decree fervently. A protest movement began to take shape in the rural community led by a lawyer and former soldier named Heinrich von Gagern. In the ensuing years he would become the focal point of the Liberal political movement in Hesse-Darmstadt.

Heinrich von Gagern

Apparently oblivious to the unrest in the countryside, Ludwig II followed his forced recruitment decree with another ordering the new members of the National Guard to assemble for training immediately. This new decree was met with even more fervent protest than the last. How could the Grand Duke call them away from their farms now before they had even the chance to plant their crops? How would their families survive while they were away? The mood rapidly turned dark with many declaring that they should refuse the Grand Duke's call and resist him by force if necessary. Only through the efforts of cooler heads such as Heinrich von Gagern was talk of rebellion quenched. In the end, the new National Guardsmen reported for duty, but they left communities seething with resentment behind them.

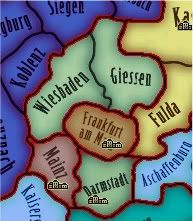

By April Ludwig had his army and a 50,000 man National Guard that was nearing the completion of it's training. All he needed now was an enemy to pit it against. He needed a nation that was close by, rich in resources, and (most importantly) not a member of the German Confederation as attacking a member state would put Hesse-Darmstadt at war with the entire Confederation. These criteria really left him with only one choice: the British client state of Hanover. The army was given it's marching orders and war was declared on April 15, 1837.