Enewald said:

Who is this dirty separatist leading the secession?

Sadly, I never did take notes on who was the leader of Nicaea when prepping for this chapter on the developments of the Byzantines perspective.

Dr.Livingstone said:

Do you have the Lux Invicta DLC?

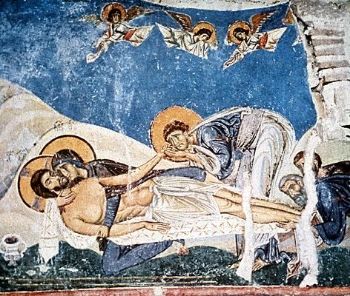

Oh heaven's no! I do not entertain such "alternative history" especially when the a-historicism is completely unforgiveable from my historical perspective. I mean, how the ERE would be "anti-Christian" is beyond me, and the eastern Mediterranean was the epicenter of Christianity by the second half of the second century and had come to dominate all the major urban Roman cities: Corinth, Athens, Constantinople, Nicaea, Aleppo, Jerusalem, and Alexandria by the third century. Plus the Roman "Cults" never had much power in the east.

Steven Hijmans article

"The Sun Which Did Not Rise in the East" (1996) shattered the old notions that the Cult of Sol Invictus had significant influence in the east, and on that aside, as someone who sort of "specializes" in the Cult religions, I have serious misgivings with "popular" keyboard warriors spewing laughable claims about the Cult Religions that no scholar accepts, like the idea the Mithraism goes back to the 6th or 5th century BCE and is a forerunner to Christianity, the earliest archeological records uncovered shows that the Cult emerged in the second half of the First Century, found along the Rhine River cities under the Roman Empire. The rise of internet revisionism by emotional bloggers is a serious threat to the proliferation of true historical knowledge, especially since many of us from an academic POV believe "they" are winning. Just like the conservative blogosphere's obsession with "Sharia" Law. If they actually studied Islamic Law and history, as I just barely covered in concentrated studies, they would know that Sharia Law is nothing more than the laws that govern a particular land/country: Turkey, Syria, Saudi Arabia, etc., all have different versions of "Sharia" which is not the monolithic entity that certain bloggers who shall not be named claim. :glare:

I understand the popularity of such a-historicism but I mean, as a historian, it would at least have to follow some sense of plausibility for me to consider (like the isolationist movement in the USA coming to power in 1940 and not getting involved in WWII and thereby allowing the plausibility of Germany's victory, which is still debatable, but the isolationist movement was so strong in 1940 that revisionist historians who I shall not name have even come up with the idiotic dribble that FDR and the pro-war lobby staged America's entry into WWII to counter their influence, like the "America First" Lobby). The Sassanids would have never been able to stop the expansion of Islam either...

As I always say, history only gets one run.

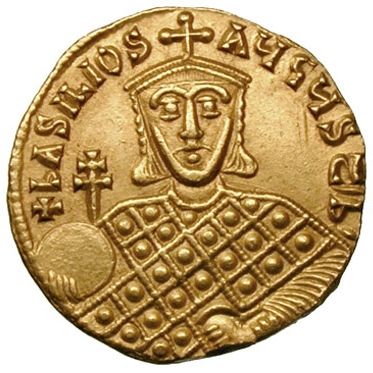

Well, Basil didn't want an easy life I am sure.

I can't off the top of my head how much civil discord Basil I had to deal with irl - but I seem to recall there was some? Or am I mis-remembering?

Basil I did face a lot of civil discontent during his reign, but his ability to win over the rebellious factions paved the way for the historical Macedonian Renaissance.