VI: Vindico

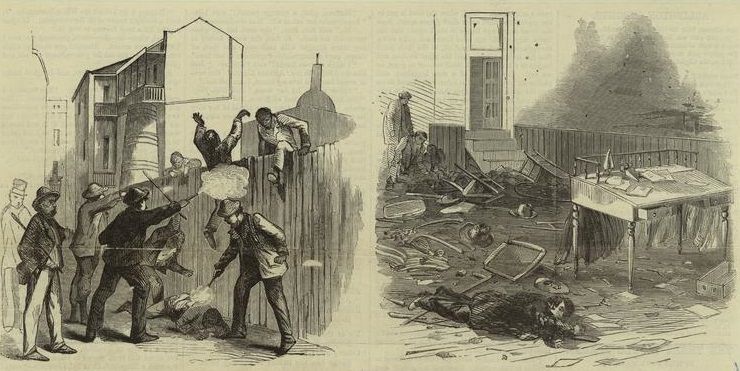

Scenes of Destruction in the Former Confederacy

The United States had won a mighty victory in 1863. It had preserved its young republic and finally abolished slavery, removing the great paradox that had vexed the Founding Fathers. The question was could the victory be made actual and permanent? Could it be proved the mighty effort had been worthwhile? In the end the purpose of the war had surpassed secession, even emancipation. For many it had been a war for democracy, liberty, equality; for the last, best hope on Earth. Not just the living but the half a million dead seemed to implore for a future worth the cost. The opportunity seemed promising. The South lay prostrate and passive, even hopeful perhaps, craving civil government and settlement after the chaos and ruin of the Confederate experiment. And then there were the African-Americans, the freemen of the North and the ex-slaves of the South. Hundreds of thousands had served the Union, as soldiers, sailors, scouts, labourers and tens of thousands had died in that service. They had earned the citizenship they longed for; if nothing else victory needed to mean the end to the Southern racial hierarchy, surely? It was this multitude of hopes and fears that lay on Lincoln’s shoulders. He had seen the Union through the worst conflict in its history and now before his first term as president was even ended he would have to captain America’s next project, the great Reconstruction.

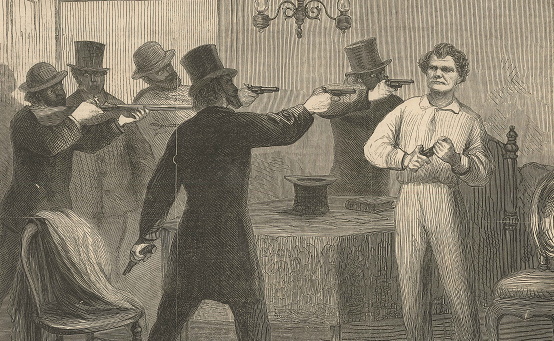

An interruption was to come however. On September 17th, only hours after news of the Pensacola Capitulation had broken, the noted Maryland actor and Confederate sympathiser John Wilkes Booth approached Lincoln near Anderson Cottage, his retreat on the outskirts of the capital. The President was walking on a public path with his wife and had no reason to be suspicious until Booth drew his pistol at point blank range. The assassin yelled ‘Deo Vindice!’ and pulled the trigger [1]. The pistol backfired and, perhaps in a gut reaction in defence of his beloved Mary, Lincoln punched Booth square in the face, downing the gunmen with a broken jaw before bodyguards could intervene [2]. Beyond Mary’s nerves and Abraham’s bruised knuckles the Lincolns escaped unscathed. Others were not so lucky. Booth had only been part of a larger conspiracy to decapitate the Union leadership. While George Atzerodt, charged with killing Vice-President Hamlin lost his nerve, his colleague Lewis Powell approached the home of William Seward, the Secretary of State. Claiming to the servants he was bringing an urgent telegram he gained entry to the house. He shot not only Seward but his son and Assistant Secretary, Frederick who attempted to rush Powell on hearing the first gunshot. Both men died within minutes [3]. Powell would be caught two days later and eventually executed for the crime alongside Booth and Atzerodt.

Execution of Powell, Booth and Atzerodt at Fort McNair, Washington DC, December 7th 1863

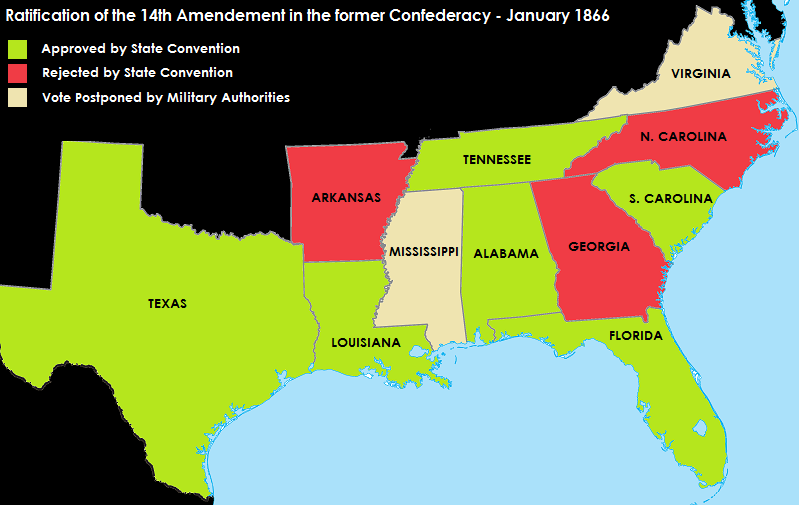

The murder of the Sewards not only robbed the State Department of two of its finest minds but coming so soon after the war’s end poisoned Lincoln’s message of reconciliation. Many, particularly in the Radical Republican camp believed the conspiracy had been a ‘fail-safe’ concocted by the Confederate leadership. Calls for treason trials against Davis and others rose in volume with even the President himself, grieving over the loss of a close friend, debating the possibility for several days before deciding against it. He was insistent the Union would be rebound without recrimination and, taking advantage of Congress’ autumn break, he set about it swiftly. Lincoln’s offer to the South, based on the model established in wartime Louisiana, was lenient. States would be readmitted to the Union following ten per cent of the population pledging allegiance to the United States, ratifying the upcoming Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery and granting suffrage to all black men who were literate or had fought for the Union. Confederate veterans would also be barred from the conventions creating the new state constitutions [4]. The Ten Per Cent Plan and limitations on suffrage outraged Radicals who by now dominated Congress. When they returned in December, led by Senator Charles Sumner and Representative Thaddeus Stevens, they were ready to do battle with Lincoln.

In early 1864 the White House and Congress were embroiled in a crisis. In January the Radicals had passed the Wade-Davis Bill, requiring the majority of a state’s male population to pledge allegiance (known as the Ironclad Oath) before re-admittance, only for Lincoln to veto it. In retaliation both Houses refused to sit Congressmen from states already readmitted, namely Louisiana, Tennessee and Virginia, and promised to do likewise to other Southern states [5]. Lincoln had hoped to swiftly reinstate the South but he now made use of military governors to keep Reconstruction strictly under Presidential control, granting loyal politicians like Andrew Johnson military rank to oversee the project. Although he was the ‘Great Emancipator’ and beloved by many in the party ranks, the President was becoming increasingly isolated from the Republican mainstream, which in turn had moved closer to the Radical position during the war. This finally was made clear in March when the Thirteenth Amendment, a long sought after goal of the Republican Party was held up in the House of Representatives. It was not Democrats and conservatives who were delaying it but in fact Thaddeus Stevens.

Thaddeus Stevens (L) and Charles Sumner (R)

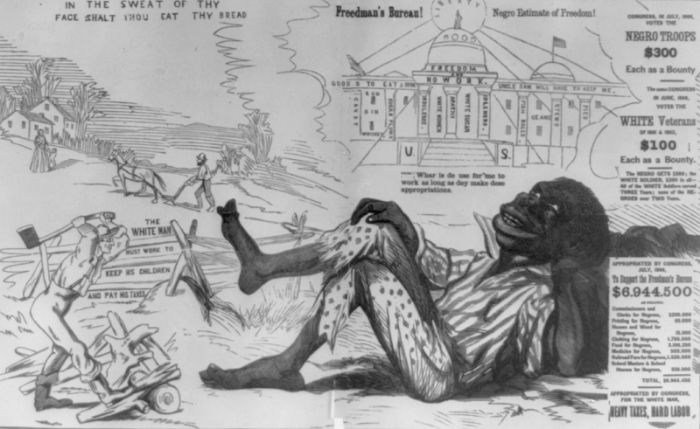

The crisis had now reached a point were those most dedicated to abolition were willing to hold off in the name of spiting the President. Lincoln realised a solution had to be found and gathered the Party leadership to talk. Over several weeks of compromise and graft the President, Sumner and Stevens came to a result. The Ten Per Cent Plan would stay; in return a new Amendment would be brought through granting universal suffrage to black men. Further details for Reconstruction were laid out, with Lincoln reassuring the Radicals of his intentions. A Freedmen’s Bureau would be established to help ex-slaves and white refugees. This would range from education to legal aide to land distribution. The latter was the most controversial. Although no land was to be seized in peacetime, large tracts taken under the wartime Confiscation Acts were to be parcelled out to blacks and whites alike [6]. This was to avoid charges of advantaging freemen (it didn’t work) and in an effort to cut off poor whites from the landowner aristocracy who were seen to be the instigators of the war. The Republicans, Lincoln included, also no doubt hoped the creation of a smallholder class in the South would increase support for their Party in the region. 1864 was an election year after all. The final part of the land plan although accepted by Congress and the general public for the most part would haunt Lincoln’s historical legacy and that was the handing of land in the Indian Territory over to black settlers.

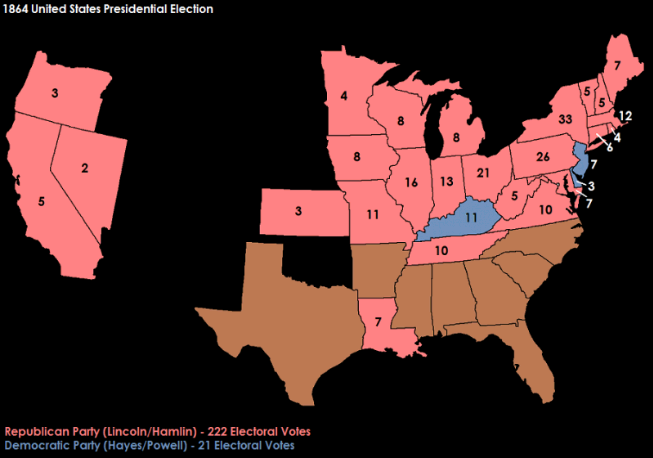

Although the Five Civilised Tribes of Oklahoma had not uniformly sided with the Confederates, thousands of Native Americans had joined the rebellion while many tribal leaders had signed treaties of alliance or neutrality with Montgomery. Primarily this had been amongst the Cherokee and Choctaw, who suffered the majority of the seizures, prompting violence between the tribes and Union soldiers under the command of General Grant who had originally suggested the idea to Lincoln. Over the next decade thousands of black families migrated to the region under Freedmen’s Bureau supervision. This trend would continue at a weaker pace following the Bureau’s abolition and by 1900 the ‘Indian Territory’ would have an African-American majority. With the standoff between Lincoln and Congress now over, the Republicans prepared for the upcoming November elections. There was still distrust of the President in some Radical circles, and John Fremont, the party’s first presidential candidate in 1856 and a vocal critic of Lincoln announced he would put himself up as a candidate in May. There was also a small but significant campaign to draft General Alexander Clemens, the main hero of the Union war effort, as the Republican candidate. However when the Party gathered in Baltimore the threat to Lincoln’s re-nomination proved illusory. Fremont soon discovered much of his support had come from Copperhead Democrats hoping to spoil the all but assured Republican victory and at the convention failed to get into double digits on the ballot. Clemens meanwhile gained 25 votes on the first ballot, prompting him to make a speech confirming his support for President Lincoln. Following a revision Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin were officially endorsed on the first ballot with all but seven votes.

Despite efforts to make it a biracial organisation, the Freedmen's Bureau was the target of near constant racist criticism

The Democratic convention did not take place until August in Chicago and proved a dismal affair. The Party had been divided since the 1860 election, first between northern and southern factions and then following secession between War Democrats and Peace Democrats. A Republican administration, led by a popular President and endorsed by several prominent generals like Clemens and Grant, had crushed the Confederacy decisively. Now that Lincoln and the Radicals had put aside their differences there seemed to be nothing stopping a crushing GOP victory at the polls, particularly as much of the South would not be taking part in the election. The assumed frontrunner Governor Horatio Seymour of New York vocally declined nomination as did former President Franklin Pierce, a man often considered one of the worst leaders in American history and who had openly supported the Confederacy [7]. That such a man would be approached at all shows the level of desperation within Democratic ranks in 1864. Eventually a ticket was cobbled together with Major General Henry ‘Gunner’ Hayes being nominated for President and Senator Lazarus Powell of Kentucky chosen as his running mate. Hayes, touted in the campaign as the conqueror of Virginia was chosen to appease War Democrats and capitalise on his popularity with common soldiers, while Powell supposedly appealed to Peace Democrats and the Border States.

However Hayes had ultimately been replaced in Army affection by Clemens, while Powell was rabid in his criticisms of Lincoln to the point the Kentucky Assembly had attempted to have him impeached in 1863. The two men, far from balancing the ticket only contradicted each other. Hayes, trying to tap into Andrew Johnson’s tough rhetoric promised he would see the South pay for the rebellion unlike that flip-flopping Lincoln. Powell meanwhile declared the Republicans tyrants who had installed a Negro dictatorship backed by Union thugs, thugs assumedly like Hayes. The Democratic campaign was chaotic, its only clear points being opposition to black suffrage and the character assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The Republicans meanwhile provided a detailed plan for Reconstruction that would be implemented by an experienced President and an experienced Congress. This would include tariffs to protect domestic industry and ‘internal improvements’ the keystone of American Whiggism to literally rebuild the shattered South. The GOP had the support of abolitionists, New England liberals, industrialists, smallholders, African-Americans, radicalised former Democrats like Nathaniel Farnsworth and the lion’s share of Union veterans who numbered almost one million former soldiers and sailors. The only thing surprising about the result was that Powell actually won his home state.

----------------

[1] The Confederate national motto; translates loosely as ‘God is my vindicator’.

[2] Lincoln was a strong man and is actually enshrined in the Wrestling Hall of Fame for his ridiculous 300-1 record. If the Secret Service weren’t there I’m sure he would have tombstoned Booth through a picnic table.

[3] Both Sewards were very lucky to survive IOTL, with Frederick actually having the assassin’s revolver pressed into his temple only for the chamber to jam and the assassin run rather than pull the trigger a second time. His father on the other hand survived numerous stabs to the neck thanks to a brace his doctor had given him a few days earlier.

[4] Trying to figure out what Lincoln intended for Reconstruction is difficult but these are the main points he mentioned prior to his death IOTL.

[5] Kentucky and West Virginia are not considered part of Reconstruction.

[6] This was part of the Bureau’s original intent but Andrew Johnson used his presidential authority to hand all land confiscated back to its original owners. Lincoln praised the wartime farms set up and run by ex-slaves so I imagine he would be fine with it en masse in peacetime.

[7] Pierce was approached IOTL too, the Democrats really were that desperate.