Blood and Iron - An Interactive Prussian AAR

- Thread starter Tommy4ever

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

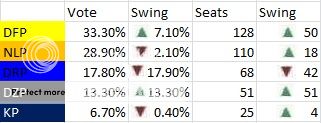

Final Results:

DFP: 15

NLP: 13

DRP: 8

DZP: 6

KP: 3

Total Votes: 45, an increase in the turnout by 7.1%.

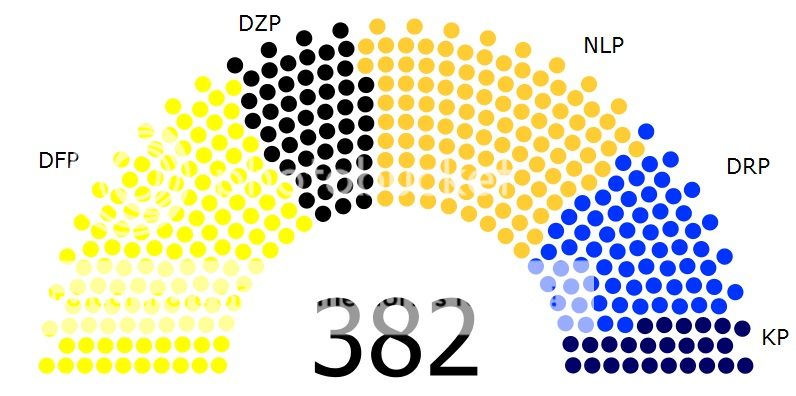

Composition of 382 seat Reichstag:

DFP: 128

NLP: 110

DRP: 68

DZP: 51

KP: 25

With 192 seats required for an absolute majority this election came very close to unseating the regime parties as the DFP won a plurality of the vote, becoming the Reichstag's largest party. But they fell short of being able to unseat the regime parties. Instead the NLP-DRP coalition is expanded to include the KP and keep the existing government in place, although it is due for a reshuffle.

DFP: 15

NLP: 13

DRP: 8

DZP: 6

KP: 3

Total Votes: 45, an increase in the turnout by 7.1%.

Composition of 382 seat Reichstag:

DFP: 128

NLP: 110

DRP: 68

DZP: 51

KP: 25

With 192 seats required for an absolute majority this election came very close to unseating the regime parties as the DFP won a plurality of the vote, becoming the Reichstag's largest party. But they fell short of being able to unseat the regime parties. Instead the NLP-DRP coalition is expanded to include the KP and keep the existing government in place, although it is due for a reshuffle.

This was a close call, though the stability and prosperity for Germany continues, I am worried about the next election though, but that is a long ways away. This is the best AAR I've read in a long time. :3

I shall hope that this election result will clearly show to the leadership of the NLP that they must turn away from their current path and return to the ideals of liberalism.

The Election of 1869

As Germans prepared for their first election as a unified country, still basking in their military triumph over France and Russia, not to mention the ecstasy that accompanied the announcement of unification there were still very important political battles to be fought. With Chancellor Bismarck intent on pushing through authoritarian measures to ensure the unity and stability of the new Empire in the Kulturkampf and the Anti-Socialist Laws and the future direction of the German Empire at stake Germany’s first elections were bitterly contested.

The results of the election appeared quite spectacular. The Chancellor’s own party was the greatest victim – losing half its share of the vote and almost as large a portion of seats – losing out to its traditional allies on right and left, as well as the DFP across North Germany and failing to penetrate the South. In the South a new, anti-Bismarckian formation arose in the form of the Centre Party which was opposed to authoritarianism and Prussian domination, the party established itself as the largest in the South German states but found little support beyond the Catholic community. Elsewhere the National Liberals and Conservatives managed to hold their share of the vote and make minor gains, mostly in the North – although the NLP had managed to find a following amongst strongly pro-Berlin Southerners. Finally, the DFP looked set to make a genuine bid for power as it amassed as much as a third of the vote – being the only party to find a broad base in both the North and South of the country it claimed to be Germany’s only truly national party.

Unfortunately for the liberals and quasi-Jacobins of the DFP their radicalism left them politically isolated despite of establishing themselves as the Reichstag’s largest party. Surviving the dilution of their vote caused by the unification, and the challenge of the DFP the Prussian dominated pro-Berlin elites who had led Germany to unification retained power – forming an alliance between the National Liberals, the Reich Party and the Conservatives with a razor thin majority in the Reichstag.

The results of 1869 had a major impact upon the National Liberals, despite merely hanging on to their share of the vote their political position had been much enhanced with the decline of their previous collaborators on the right and the absence of any alternative to their government. With the threat from the radicals of the left causing great concern the right of the NLP looked to take control of the party leadership. This involved a putsch against the party’s most senior leader, Max von Forchenback – the man who had been Prime Minister of Prussia since 1861 was identified as a sympathiser with the party’s more ideological and liberal wing and was ousted from any position of power, being relegated to the status of a back benchers. As several other members of the party’s left were picked off former Prime Minister of Hannover Rudolf von Bennigsen was established as the new leader of the party. Although only a little less liberal than von Forchenback himself, Bennigsen was willing to give the party’s right the power it craved whilst keeping the NLP a unified force. From this position of strength the NLP approached the Reich Party and the Conservatives.

Although Bismarck was allowed to remain Chancellor he did so on the condition that he separate any official ties to the Reich Party and accept a government dominated by NLP Ministers. With Bennigsen taking over as Prime Minister of Prussia, and being granted the newly created position of Vice Chancellor one half of the Ministerial positions in the new government were granted to NLP members, the remainder divided among the DRP, Conservatives and some handpicked independents. With the National Liberals achieving the total control of the economy they had sought coalition also agreed to pass through the policies of the Kulturkampf and the Anti-Socialist Laws.

In the face of the rise of an anti-regime opposition with impressive levels of electoral support the Prussians had bitten back with a radical turn of their own.

The results of this election were expected, but disappointing for all moderates nonetheless.

Though apparently free and fair, the forces of truth and justice were dealt a blow as the north grows increasingly reactionary and radical.

We shall see what comes of this..

Though apparently free and fair, the forces of truth and justice were dealt a blow as the north grows increasingly reactionary and radical.

We shall see what comes of this..

I shall hope that this election result will clearly show to the leadership of the NLP that they must turn away from their current path and return to the ideals of liberalism.

Indeed, but it equally shows that the DFP has to step back from the precipice of insanity and return to a more moderate -- though still undeniably radical -- strain of liberalism. Germany voted for a liberal majority government, and it was only the extremism exhibited by the DFP that prevented a NationalLiberale/Zentrum/DFP coalition.

Although I voted Zentrum, im glad to see Bismark stay on as Chancellor. I think that his realpolitik is the best foreign policy direction for Germany, and his leadership is something I respect. However, Kulturkampf is not so much a good idea, so I voted my consience on that. However, I wasnt as opposed to the Anti-Socialism law as my party platform states, but I guess that beggars can't be choosers. in any case, great update.

The National Liberals are sell-outs! Booo!

Says the Herren who once voted for the KP.

Played through the next section of the AAR. Update tomorrow as usual - looking forward to this one and the coming election.

Indeed, but it equally shows that the DFP has to step back from the precipice of insanity and return to a more moderate -- though still undeniably radical -- strain of liberalism. Germany voted for a liberal majority government, and it was only the extremism exhibited by the DFP that prevented a NationalLiberale/Zentrum/DFP coalition.

Or because the author wanted to keep Bismarck in power.

I would have to concur haha.Or because the author wanted to keep Bismarck in power.

Expected but still interesting results. Though that might have been the last time I vote for the NLP, barring anything spectacular they manage to achieve. Or a very good sounding platform XD

Indeed, but it equally shows that the DFP has to step back from the precipice of insanity and return to a more moderate -- though still undeniably radical -- strain of liberalism. Germany voted for a liberal majority government, and it was only the extremism exhibited by the DFP that prevented a NationalLiberale/Zentrum/DFP coalition.

I do agree with you, herr Tanzhang. I did not expect the DFP to win this election, indeed my vote was more in protest. Alas it would seem that didn't at all serve its purpose; the NLP have travelled farther right and the DFP are likely to remain as radical. It would seem the conservatives and reactionaries will continue to gain on the liberal divide.

I'll have to see whether or not I vote NLP next time... I don't like the look of this "putch" at all.

Sssshhhh!Says the Herren who once voted for the KP.

Can we do some wheeling and dealing in this AAR? I for one only voted DFP to see Austria be annexed into Germany. I'm sure there are some more of my fellow DFP colleges that did the same.

1869-1873

Three Hurrahs!

Three Hurrahs!

Following the unification and the re-election of a Bismarck led government, now dominated by the National Liberals, the German state struck out with impressive self-confidence as it looked to forge a new nation and raise Germany to the status of the world’s greatest power. The centrepiece of the government’s internal policy was the Kulturkampf directed against the power of the Catholic Church and specifically the powerful Ultramonatist tendency within it and ethnic minority populations. With the strength of the National Liberals within the government there was no moderating influence on the Kulturkampf.

In the first years after unification the measures of the Kulturkampf rapidly grew in their number and intensity – the Jesuits were banned and expelled from Germany, significant amounts of monastic lands were confiscated by the state, religiously run schools (in practise almost exclusively Catholic run institutions) were placed under heavy state supervision – some being wholly taken over by the state, any political statements by the clergy judged to be anti-statist were punishable by imprisonment (by 1873 just under one half of German bishops had been placed under imprisonment), all clerical appointments required the notification and agreement of the state, by the end of 1873 the German state was attempting to take over the training of all clergymen – thus instilling them with a German national outlook all associations from trade unions to social clubs based on religion and organised around the Church in Catholic areas came under suspicion. Although the French minority of Alsace-Lorraine and Luxembourg and the Danes of Schleswig-Holstein escaped the worst excesses of the Kulturkampf the Slavs of the East of the Empire witnessed the worst tyrannies of the policy as there were attempts to enforce the German language and break up all national based organisations. Internationally the Germans used their close relations with the Italian government to place heavy pressure on the Papacy to accept the effective Germanisation of the Catholic Church within the Empire – by 1874, in spite of heavy pressure the will of the Catholics had not yet been fully broken and the policy was becoming divisive even among the North Germans as many became uneasy with the zealotry of the liberals.

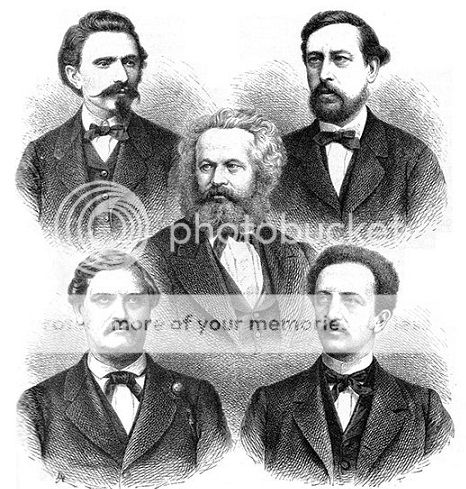

Top row: August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht of the SPAD, Middle: Karl Marx the most influential thinker of the German labour movement, Bottom row: Carl Wilhelm Tölcke and Ferdinand Lassalle of the ADAV

Just as the repression of the Catholics had not managed to crush the resistance of the Catholic community the Anti-Socialist Laws (the other centrepiece policy of the government) failed utterly to destroy the socialist movement – instead driving it towards unity and resistance. With openly organised trade unions and socialist parties banned the movement was forced into a status of semi-illegality as officials proved far less aggressive in their implementation of measures than they had in the case of the Catholics. In the face of adversity the various socialist currents – chief among them the SPAD and ADAV – banded together to form the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP) in 1872, adopting the explicitly socialist (although non-revolutionary) Gothe Programme.

Following unification the German government looked to massively expand the standing army so that the German Empire might reaffirm its almighty military position in continental Europe – the aim to make Germany powerful enough to face any two continental Great Powers alone. Accompanying the replenishment of losses sustained in the recent German War the standing army was increased from a pre-war level of 234,000 to 378,000 by the completion of the programme in the Spring of 1873 – an impressive increase in the size of the army by 61.5%, the German Army had made a clear commitment to its goal of military domination in Europe. However, the funding required by the land army meant that the navy – reduced to virtually nothing during the German War – received no attention leaving German shipping lanes, and the German shoreline under threat in any future conflict with a naval power.

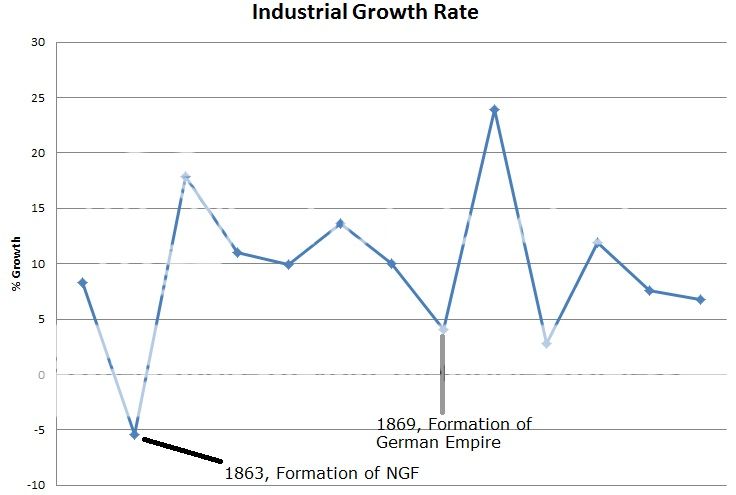

Economically the return to more overtly laissez faire economics from 1869 with the National Liberals gaining exclusive control over the state’s economic policies saw the transformation of Germany continue at pace. With the over exuberance of the first year of unification witnessing a mind boggling industrial growth rate of 23.9% the country returned to sobriety the following year as industry largely stagnated before a more stable but apparently decline growth rate settled in from 1871 through 1873. During this time the population of the Empire as a whole rose by 3.5 million whilst key social groups expanded noticeably with the class of industrialists growing from around 16,000 to 26,000 and industrial workers increasing in number by more than ¼ of a million to 920,000 – meaning that 8.1% of the population now consisted of industrial workers with the Rhineland, the area around Munich, Silesia, Saxony and above all Brandenburg being especially developed. The German economy surpassed Britain at the beginning of the 1870s and remained second only to America. The impressive nature of the German economy, and the growing power of the German nation was highlighted in 1871 with the inauguration of the Kiel Canal – which opened up a new shipping lane between the Baltic and North Sea, an incredible technical and economic achievement by any measure.

Germany’s diplomatic goals following unification were to isolate France, repair relations with Austria and break up the Franco-Russian alliance – the Bismarck controlled Foreign Ministry was to find successes beyond its wildest dreams in the early 1870s. With the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1870 marking a shift in Habsburg policy from an outwardly looking ambition to exert influence abroad to an inwardly looking eagerness for internal stability and security the Empire became far more passive and happily accepted German overtures of friendship through the 1870s as relations between the two Germanic Empires radically improved.

Germany’s diplomatic position among the Great Powers of Europe was enhanced massively by the role the Empire played in a major diplomatic crisis that erupted in the Balkans in the Summer of 1871 as Ottoman oppression of various Christian populations saw Russia call for war in order to separate their allies – the Eastern Christians – from the Empire. The prospect of an Ottoman collapse terrified the Austro-Hungarians who feared being surrounded by Russia and her allies and angered the British who had twice fought Russia in order to protect the integrity of the ‘Sick Man of Europe’. As Russian attempts to call upon her French ally to provide international backing resulted in Paris giving the Tsar the cold shoulder Germany played an impressive conciliatory role as Europe’s peacemaker.

A German diplomatic mission to Saint Petersburg – headed by Chancellor Bismarck himself – managed to convince the Tsar to gracefully step down from his calls for war in exchange for face saving measures taken by the Ottomans to end repression against the Christians of their Empire. The failure of the French to stand by their ally and the warm approaches of the Germans left the Franco-Russian alliance hanging by a thread. At the same time the Austro-Hungarians and British lapped praise on Berlin as the German reputation as Europe’s bad boy and the biggest threat to the balance of power began to subside in the light of the German role in averting war and saving the Ottoman Empire from Russian invasion.

With amicable relations with Britain, Austria-Hungary and even Russia the German diplomatic position was extremely strong. Things were only going to get better for the Germans as competing French influences were beaten out of the Low Countries – Belgium and the Netherlands agreeing to alliances and German influence expanded into Scandinavia where Denmark came wholly under German influence and Sweden agreed to an alliance. With the military alliance with Italy – a country almost rapid in its pro-German mania from the political elite down through the general populace – preserved France appeared to be in a strategically hopeless situation. Germany was surely safe from French attempts to reclaim Alsace-Lorraine.

Yet in times of collapse and desperation regimes can act with little apparent logic. Successive defeats to the Germans in the 1860s had shaken France and the Empire of Napoleon III to its very core. In 1860 France had been Europe’s greatest military power and most powerful economy (excluding Britain). In a little over a decade she had been completely outstripped by any and every measure by Germany. Having barely survived the flames of revolution in the aftermath of defeat in 1869 that had seen Alsace-Lorraine lost the French situation continued to decline rapidly in the early 1870s. With opposition at home becoming irresistible France’s diplomatic position came under dire threat. With his grip on power horrendously loose and the collapse of his regime an apparent inevitability Napoleon III had turned towards delusion. Believing Russia would honour her alliance, that the anti-Catholicism and expansionism of Germany would alienate Italy from her alliance with Berlin and bring Austria-Hungary into an anti-German League and that France still possessed great military power the Emperor recklessly declared war upon Germany calling for the liberation of the French populations on Germany’s Western frontier and of the Catholics of the German Empire.

This was a miscalculation on an incredible scale. Seeing the Franco-Russian alliance for the one sided pact that it was the Russians abandoned France, even the Swiss refused to march to war for a second time in half a decade. Germany alone, following its most recent military expansion, possessed the strength to crush the French Army – alongside its Italian, Danish, Dutch and Belgian allies it was clear within a couple of weeks that French defeat was totally unavoidable. The failure of French diplomacy and the country’s national stagnation had doomed it to the ranks of the second rate ‘Great’ Powers.

With the war breaking out in early August the regular French Army was overwhelmed within a matter of weeks – its last great stand coming near Brugge in North-Western Belgium. With the regular army in disarray France turned to its last line of defence – the mass conscripts who had saved France from destruction during the Revolutionary War eighty years before, yet even with the fervour of the new recruits the French suffered a horrendous defeat around Paris in which 85,000 men were lost. With the collapse of French power and the occupation of the Eastern third of the country one might have expected the German government to be riding high on the public enthusiasm for its victories.

Many conservatives had been growing increasingly uncomfortable with excesses of the Kulturkampf and the laissez faire economic policies of the government – creating a strong sense of resentment of the National Liberals among their allies. Moreover Bismarck tenuous position at the head of a National Liberal dominated government had seen the Iron Chancellor clashing ever more frequently with his NLP backers over both domestic and foreign policy issues – notably the NLP’s calls for Germany to expand its fleet and acquire an overseas colonial Empire. The stresses of war saw the cracks in the ruling coalition grow into deep fissures.

With it becoming increasingly clear that France was to be utterly defeated the National Liberals were taken over in a frenzy of imperialist and nationalistic chauvinism demanding that France surrender a substantial part of her colonial Empire in exchange for peace. Such a policy clashed with the conservative right that did not wish to lock Germany into an unbreakable cycle of hostility with France, nor acquire an overseas Empire that offered Germany little politically or economically aside from conflict with the British and worthless investment. With the government rapidly falling apart the Conservative Party and the Reich Party reunified after a decade of separation as the German Conservative Reich Party (DKRP) with the goal of capturing power independently of the National Liberals. In December 1873 the newly created DKRP withdrew its support for the government leading to Germany’s second election since unification.

How did a minority party leader even become PM?

So what all colonies did you get? Liberate Algeria?

So what all colonies did you get? Liberate Algeria?