Chapter One: John V Palaiologos

January 10, 1356AD:

It was a mild day in Constantinople. The old city bustled with life, the sounds of market and wharf creating a din and the salty scent of sea carried in gusts by the breeze. John V Palaiologos stood on the balcony adjoined to his apartment and looked over Blachernae and his city. He was an ambitious young man of twenty three, and he saw opportunity. I shall be the great Palaiologos, he thought to himself, and today is a good day to start. He waved over a servant and summoned his council. There was work to be done: where to start?

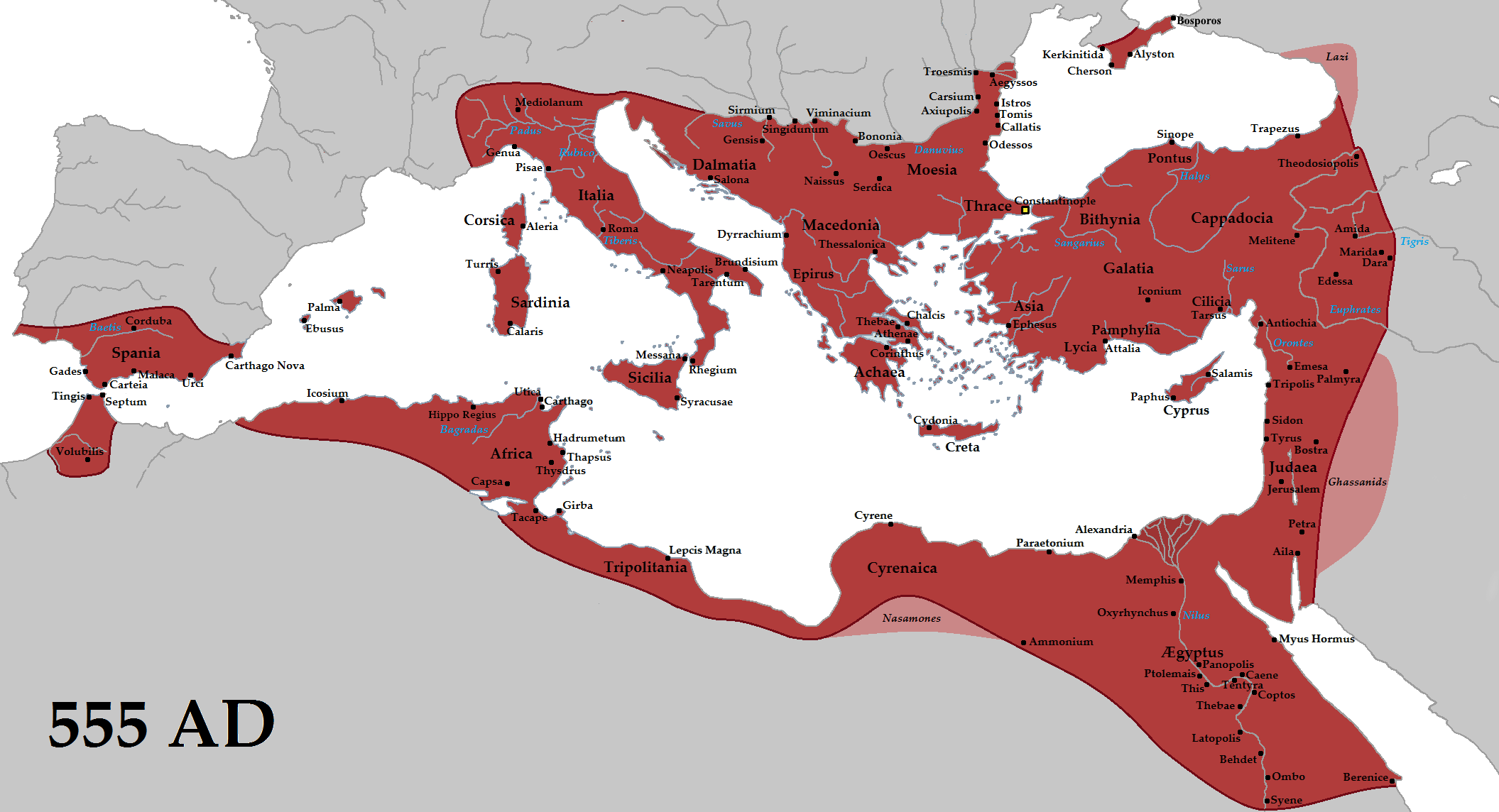

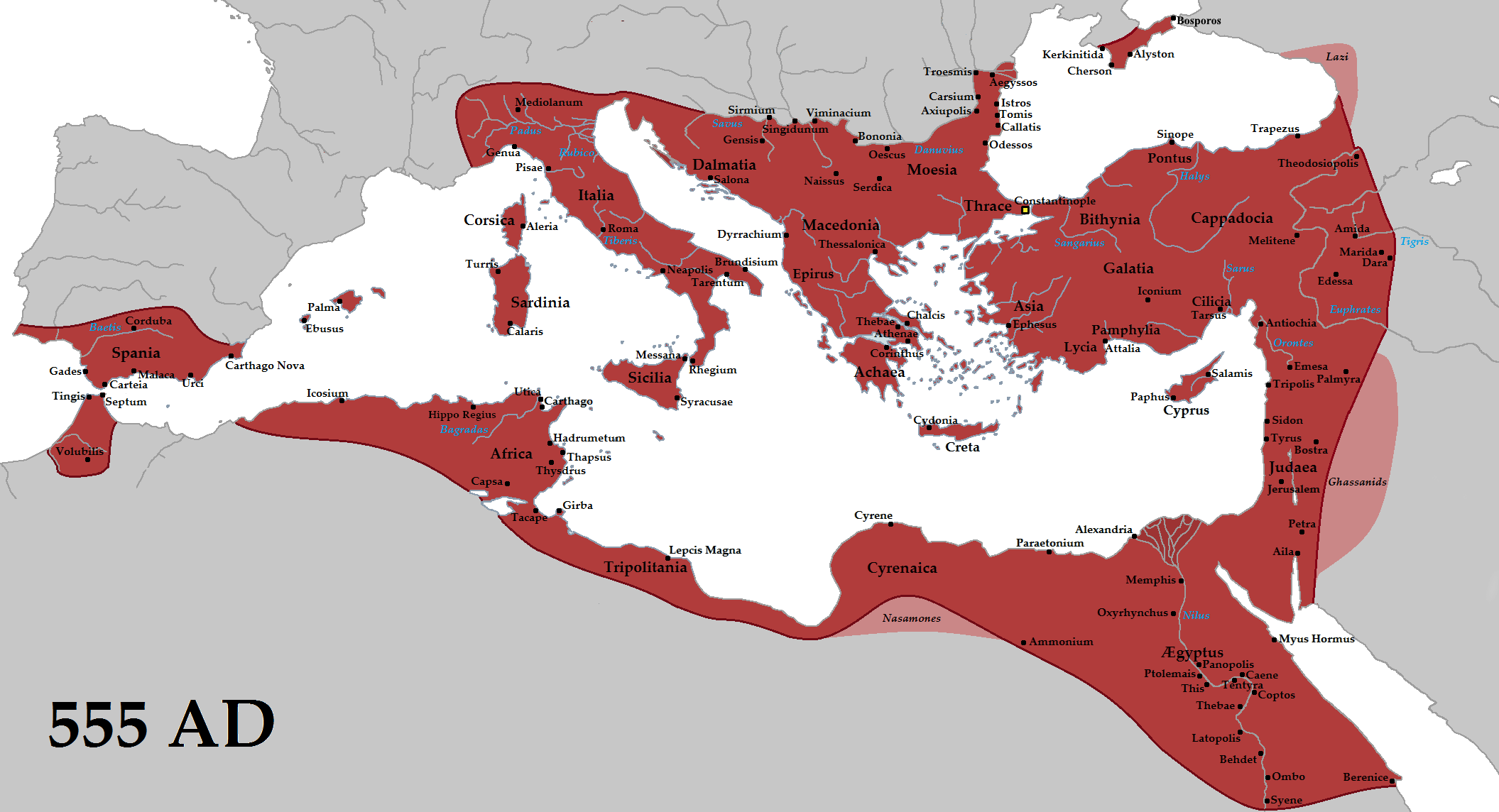

Byzantium in 1356 is smaller than it used to be, but it still has some strength: Constantinople is still a great city of Eastern Europe, while Edirne and Kozani are both respectable. Talking to his advisors, Bulgaria was mentioned several times as a worthy target, but John V was hesitant about expansion in the Balkans: he liked his chances in Asia Minor. First, however, he decided that he needed to improve Byzantium’s diplomatic position. It was well known at the time that many of the European kingdoms had disputed succession; royal marriages provided an opportunity to strengthen John’s legitimacy and influence. He sent word to his diplomats in Epirus and Serbia to offer royal marriages, which were promptly accepted.

By early March, John was ready to prepare Byzantium militarily for war. His predecessors were cautious men and favoured defensive tactics, but this would change if he was doing the invading. John’s announcement of his intentions to restore some of the old Byzantine provinces to his empire was met favourably.

May, 1356:

John had convened his council and the discussion was heated. Following his declaration of more aggressive foreign policy in March that year, relations with other nations in Asia Minor had deteriorated, particularly with Candar.

“We ought to annex Candar,” he said. “Send the messengers and ready our ships.”

“Your majesty, the Candarian King has a military alliance with the Mentese. It is likely that we would have to deal with both,” said Theodore, one of his trusted advisors.

John smiled, “I have a plan. According to my spies, Candar is impotent, its army only half the size of ours. When Mentese declares war upon us in defence of its ally, we shall crush it and then return north.”

“Your majesty, who shall command our forces? General Dimitros fell ill a month since and has not yet recovered. Shall we promote an officer?”

“I shall take command. It is true, is it not, that Caesar led his men and thereby won their respect: I shall do the same. Let it be known that Byzantium is not the decaying corpse ruled by old men, but a strong and youthful Empire entering a new age of glory!”

John V took command of the Byzantine army and set sail for the Mentese province of Mugla soon after his declaration of war upon Candar. His spies had informed him that Candar’s army would take some time to mobilise and ready itself, so he planned to first conquer Mentese before returning north. With four thousand troops he engaged the Mentese army, also of four thousand troops, forcing them to rout. Rather than pursue, the army lay siege to Mugla. A month later a thousand knights arrived by ship to bolster the Byzantine forces in Mugla.

The siege ended in December with the surrender of the defenders; Mugla was now occupied by Byzantium. John marched his men to the other province of Mentese, Antalya, to engage the remaining Mentese troops and secure control over the entire country. The battle was swift; the Mentese army was routed and destroyed. John acquitted himself as a capable leader, but the true test of his generalship was to come. The capital city of Mentese was under siege for ten months before it surrendered and the Mentese king accepted defeat and annexation. However, messages from Constantinople were grim: a Candar army had landed in Edirne and was besieging the city. To further complicate matters, the Mentese annexation had prompted the small kingdom of Saruhan to declare war on Byzantium. Very foolish.

January, 1358:

John sat in the large tent which had been his home for the past eighteen months. It paled in comparison to his palatial apartments, but his quarters were still luxurious and he was attended by servants.

“Your majesty, the Candarian army is besieging Edirne. Your council in Constantinople advises that it will fall in six months if the siege is not broken.”

“The insolent swine! Our foray into Mentese, however successful, has been too long. We must relieve the city. Is our fleet ready, Theodore?”

The advisor shook his head, “It is engaging the Candar fleet in the Sea of Varna. We shall have to wait.”

“I cannot wait while my kingdom is dirtied and damaged by my enemies. Send a message to the Ottoman sultan: we request military access.”

The sultan, surprisingly, agreed to let Byzantine troops march through his lands. The Ottomans were currently at war with England, Wales and Venice, amongst others, so perhaps it was to appease the Byzantines – in any case, John set out from Antalya to Manisa. The small Saruhan army was destroyed and John ordered his men to lay siege. As he could not afford to wait too long, but was wiser than to assault the fortified city, he sent a spy to bribe the defenders. There was no word of success or failure for a month, but finally the city surrendered in July that year and Saruhan was annexed.

The city of Edirne has fallen just days earlier, much to John’s anger. The Byzantine fleet was nowhere to be seen, so John marched through Turkish lands cross the narrow straight from Balikesir to Edirne, where he promptly destroyed the Candar army. While the army reoccupied the Byzantine province, John discussed strategy with his council. Candar was making insulting requests for a white peace, but John was set on complete annexation. He recalled the fleet from the Black Sea and shipped his army across to Kastamon, in the heart of Candar. Disaster struck, however, while he was besieging the Candarian provinces: the Mamluks, infidel scum, had declared war!

The defenceless Mugla and Antalya were quickly occupied by the Mamluks. The Byzantine fleet returned to the Sea of Marmara, where it defeated a larger Mamluk fleet and caused the deaths of thousands of Mamluk soldiers who were being transported. Alas, the Mamluks were vastly stronger militarily and another Mamluk army made it through to besiege Edirne. Once Kastamon had fallen to John’s army, he returned to fight the curs in Edirne. However, while marching through the Turkish countryside, his advisors managed to turn John’s mind from protracting an untenable war with the Mamluks: he sent a diplomat to meet the Mamluk commander to broker a peace in which the Mamluks gained Antalya and Mugla. It was a loss which he regrated, but upon his return to Constantinople, with Candar annexed and his empire at peace, John knew he had made the right decision.

He had even more reason to accept peace with the Mamluks and their allies when the sultan declared war on Byzantium in November 1361. A sizeable army of Turks crossed the border into Constantinople, engaging the Byzantine forces. Despite the defender’s advantage, John’s army suffered a loss and were forced to retreat into neighbouring Edirne, with the Ottomans in pursuit.

November, 1361:

The air is thick with dust kicked up by thousands of marching soldiers and cavalry. Constantinople lies behind them, and a pursuing Turkish army can be seen leagues away. It was a perilous retreat from the Battle of Constantinople, but John had managed to clear the enemy’s army and maintain an ordered retreat. The bedraggled men, however, knew that should the Turkish catch them in Edirne they would be slaughtered. John rode in the centre of the column: he needed a plan, and fast.

“The Turks will catch us tomorrow, your majesty. Have we any reinforcements that could assist us in a stand against them?” asked one of his officers.

“What reinforcements we had came to our aid in Constantinople; I fear we cannot survive another battle with the Turks – morale is too low, and the men are wearied,” replied the Emperor.

There was little to be done, John realised. If they could make it Edirne… but it was hopeless. Edirne was still a day’s march, and the Turkish vanguard would reach them before then. What would Justinian do, he mused. No, that wouldn’t do.

“We will disperse and minimise casualties. Send the men in many small groups into the countryside and mountains: if they make haste, the Turks will be unable to engage us again. I must make it to Edirne.”

John’s decision to disband his army was a desperate one, but also effective. Supply carts and some equipment was abandoned, but nearly all the soldiers were able to escape. John reached Edirne and had messages sent to his Wallachian allies, who were marching through Macedonia to Konzani. He would muster his forces there and then attack the Ottomans.

The Ottomans were now besieging Edirne, but John received news that Bolu had been captured by his forces. John continued raising an army in Konzani while negotiating with the main noble families in Byzantium: he called upon them to raise troops for the Empire, and was glad when they agreed. At what cost? He didn’t yet know, but the nobles delivered an army to him, which proved pivotal.

With his new forces and the help of his Wallachian allies, John expelled the Turkish from Edirne and then the rest of Byzantium. While he felt vengeful, bordering on punitive, he knew the cost of a protracted war with the Ottomans would be too great, so he settled for the annexation of Bolu and the cessation of hostilities. The war ended in 1364 after three years, and finally his empire was at peace. John now faced the high cost of maintaining his armies, so, under the advisement of his council, he disbanded ten thousand troops. The economy picked up again and he moved to consolidate power, and his reforms to Byzantine economic policy – a move towards free trade – proved successful and popular with the merchants.

A large revolt in Kastamon broke the peace in 1367. Candarian patriot rebels had risen up, and John suspected they were being funded by a foreign power. Eventually the revolt was put down, but not until the city of Kastamon had fallen to the rebels. A great consolation was the defection of Athens to his empire in May 1370 – Greek patriots had controlled the ancient city and decided to return to their former empire rather than the control of another. John seized the opportunity and recruited thousands of the rebels into an Athenian army, under Byzantine control.

It was 1371 and John V was in Manisa with the Byzantine army. His spies and informants told him that the Ottomans were under attack from Mamluks, Dulkadirians and various other infidels – he took amusement from this disunity in the Moslem world – which to him presented an opportunity. It was seven years since he had expelled the Ottomans from his homelands, and now he could have his revenge – and expand his empire. He declared war on the beleaguered Turks from his fortress in Masina and then marched onward to the Ottoman stronghold on the Aegean, Balikesir. A revolt in Masina drew half his troops, nine thousand men, back only a week after setting siege, but it was an acceptable diversion as the Ottomans posed no threat.

May, 1372:

John felt his bones creak and stroked his beard. It was almost twenty years since he had been inaugurated as Emperor, and he had spent most of that time leading his armies to glorious victory in Asia Minor. With a rueful smile he realised it had been six years since he had been in the Palace of Blachernae and longer still since he had taken in lungful of the aromatic scents of the Great Bazaar. Perhaps this would be his last campaign, he decided. Other officers had shown great promise and aptitude in leadership, so he knew his armies would be in good hands. Now was not the time to retire to court life, however.

He had taken Balikesir and the rebel threat in Manisa had been put down. He was in his tent: his army was on the move again, to take Denizli. The tent had seemed crude and uninviting years ago, but now he felt at home on the move, marching from province to province, conquering and bringing glory to House Palaiologos and his empire.

His favourite advisor, the veteran Greek, Theodore, had passed away the previous year during the siege. John didn’t like the manner of Theodore’s replacement, but the advice was sound: press the advantage and conquer the Ottomans.

By October 1373, the Ottomans had made peace with the Mamluks and now only had to contend with John’s armies. It was most displeasing that the Mamluks had wrested Bithynia from the Ottomans, as it was uncomfortably close to Constantinople and John had wanted to annex it, but the emperor was content to take the rest of the Ottoman territory. The end of the Ottoman campaign was in sight: the Turkish army had been totally destroyed, and only Angora stubbornly held out against the besieging army. John’s spymaster had disappointed him recently, or perhaps the Turkish garrisons were unusually loyal to the Sultan, for none had taken bribes to surrender early. Time was on the side of the Byzantines, as was God, at this point, however. Angora finally surrendered in November that year and now John could exact a terrible settlement on the utterly defeated Turks.

The Turks dragged out peace talks in Borsa into the new year, perhaps praying to their unholy god that the Byzantines would be struck down, but John finally achieved the peace he wanted. The Turkish women wailed and Sultan was teary-eyed when peace talks were concluded, for the Ottomans had been left with only one city, Bursa. John would have annexed all, but was advised that the Mamluks would attack Byzantium if he did so. In any case, it was a very strong settlement: the Ottoman threat had been dealt with decisively and conclusively.

John returned to Constantinople and received a hero’s welcome. Byzantium was ascendant, the people were saying. Historians were already calling John’s campaigns the Wars of Restoration, a name which the emperor was quite pleased with. He stayed a few months in Constantinople, reinforcing his armies and allowed the troops some time to enjoy the spoils of war. The Byzantine navy had not expanded at the rate of the Empire, so new galleons and transport cogs were constructed – a wise decision, hindsight would reveal.

August, 1374:

After eighteen years of near-constant war, John V was finally in his palace. The victory celebrations had died down, and some people were becoming irritating with the rambunctiousness of the returned soldiers. John didn’t quite feel at home in Constantinople, having been absent for so long. The faces in the court had changed and he found that during his absence the day-to-day running of the empire had fallen to a council of nobles – several of whom he did not know. They were all gracious and sycophantic when he entered the room, but John felt out of place. He was a warrior-emperor, a general and strategist, not a bureaucrat. He took to walking the streets of his grand old city, remembering some of the antic he had got up to as a child. Fair Constantinople was well, he decided. The decay and sense of lost glory had dissipated, and he could feel the city breathe in the winds of change and vitality. It was his destiny to restore Byzantium and that thought filled him with a great sense of purpose and confidence.

Constantinople received a diplomat from the Byzantine vassal, Morea, in late 1374 requesting military aid. The small Grecian nation clung to Balkan Peninsula like a shrub to a cliff-face. Venetian ships were seen sailing the Eastern Mediterranean, to Crete and Rhodes, almost constantly, passing the coast of Morea. Meanwhile, their northern neighbours Achaea were making deals with western powers. As such, John V and his council felt that it was time to retake the old Byzantine provinces in Greece. Late in 1374, John set sail with eight thousand soldiers from Constantinople to Achaea, declaring war. The Byzantine forces in Athens moved west through rugged countryside.

The small Greek nation was no match for the Byzantine army and was defeated by April 1375. Other powers were now involved, however.

March, 1375:

A messenger hurried to John’s tent where he was waved through by the guards.

“Your majesty, I have serious news.”

John nodded, “Do tell.”

“Burgundy has formally declared war on our glorious empire!”

John blinked and looked at his advisors, who were standing around a large wooden table, pointing at maps.

“Burgundy? Heavens, isn’t that the Frankish kingdom thousands of miles west of us?”

“I’m afraid so, your majesty,” replied a frowning officer.

“Why ever would they declare war on us?”

There was some whispering amongst the officers. “Well?”

“When you declared war on Achaea, their allies Epirus joined them in war. It appears that Lorraine had guaranteed Epirus, and Burgundy is one of Lorraine’s allies. As such, Burgundy and Lorraine are now at war with us.”

“I see.”

Another messenger rushed in while John was stroking his beard and thinking about how this news affected his Greek Campaign. “Yes?”

“Your majesty, Bohemia has declared war on our glorious empire. The Holy Roman Emperor is calling upon his Christian brethren to join him.”

“Westerners,” sighed John. “These days it seems like an emperor can hardly conduct his affairs without getting in trouble with some nation or other. Very well, we shall see which Romans shall prevail.”

To John’s surprise, a Burgundian fleet, convoying five thousand soldiers, entered the Aegean Sea. The Byzantine fleet, stationed in Athens, set out to greet them. After a short battle the smaller foreign fleet was defeated and two ships were captured. The Byzantine navy pursued them to the Gulf of Naples, but the ships managed to escape. On land, however, the provinces of Epirus were less fortunate and fell to Byzantine troops in a matter of months. To his disappointment, John decided it would be too much to annex both provinces, taking Messolonghi in a peace treaty brokered with the Bohemians. The Greek Campaign was concluded. 1376 did not see peace for Byzantium, however, as the Eretnids and their allies promptly declared war.

The ten thousand strong army in Anatolia engaged the Eretnids in Sinope before moving into Yazgod. Joh sailed out of Athens to besiege the Karaman provinces of Hamid and Conya. The tricky infidels made use of their light cavalry to elude the larger Byzantine armies on several occasions, but this served only as a diversion, as their cities fell none the less. Karaman was fully annexed in April 1377. The Eretnid capital, Yazgod, had also fallen to Byzantine troops by this point. Weariness overwhelmed John on the path from Conya to Kayseri, as the Dulkadir joined the war on the side of the Eretnids, so the aging emperor retired to Angora to oversee the war from well behind the front lines.

Aside from rebel incursions from bordering Bithynia, the war progressed strongly in Byzantium’s favour. The Dulkadir cities were taken, and it was only a matter of time until both the Eretnids and Dulkadirs were totally conquered.

Dulkadir was fully annexed in December 1378. With increasing frequency, messages arrived from the council of Constantinople urging the emperor to diplomatically prudent: his aggressive actions, though justified, were evidently giving Byzantium a bad name. Infamy be damned, the old East Roman Empire deserved to be restored. The Eretnids were annexed in 1379, so the Byzantine armies now turned to putting down revolts of Turkish patriots.

Byzantium, 1380

Interesting news arrived in early 1380 from far flung Albion. Apparently the Scots had conquered the English; John smiled at hearing the news. He was not the only sovereign making a name for himself.

John V will be back in Chapter Two for more excitement-packed conquest.