II. Opening Gambit

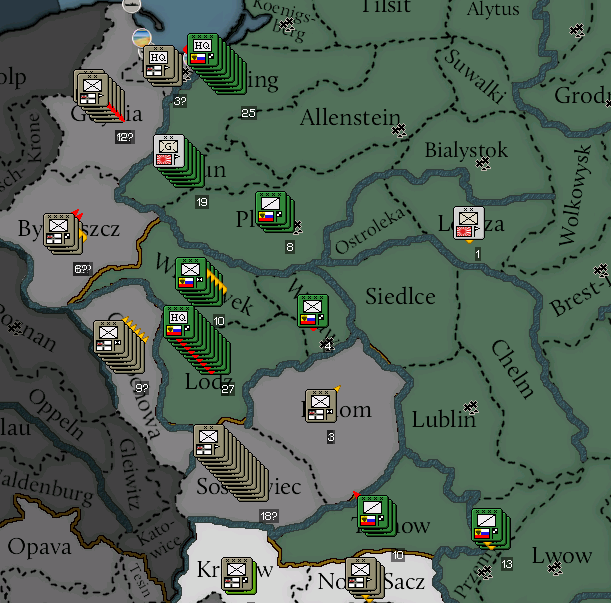

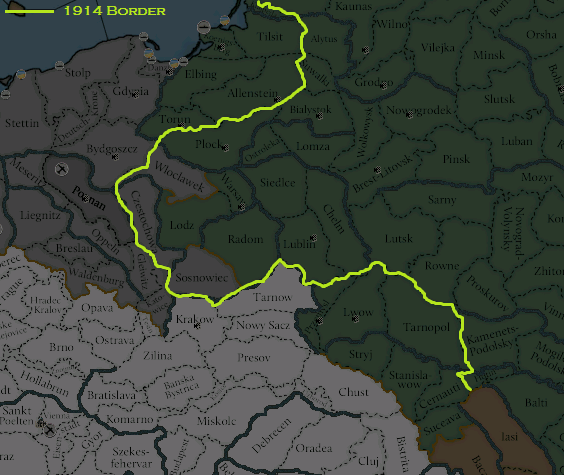

The Galicia Offensive. August 1914

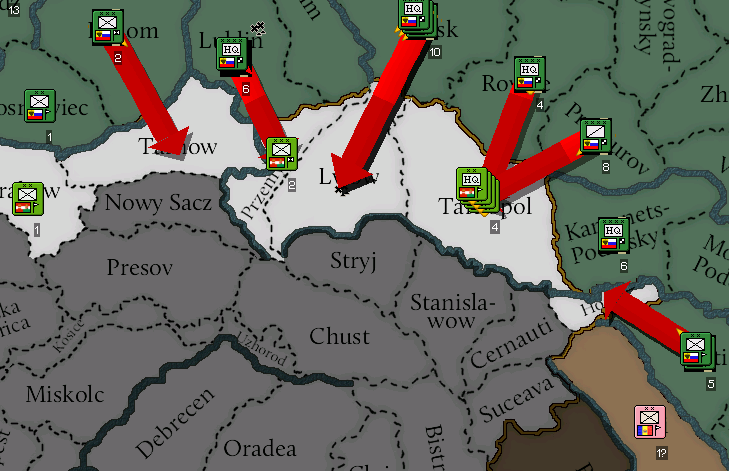

The Russian Empire endorsed her guarantee of independence to Serbia on 27th July 1914. The next day at dawn, (newly promoted) Marshal Brusilov ordered three full Armies to cross the border into Austrian Galicia. The rapid Russian response shocked the Central Powers. Unbeknownst to them, while general mobilisation had only begun three days earlier, the Tsar’s standing army, with some units travelling from as far afield as Siberia and Turkestan, had been moving towards the western frontier since the July Ultimatum had first been issued. Vladimir and STAVKA were counting on the element of surprise. They got it. Aiming for the key border towns of Tarnopol, Lemberg (Lwow) and Tarnow, half a million Russians had crossed into Austria-Hungary before a stunned Germany could even issue an official declaration of war on 30th July. Hotzendorf, the Austrian commander-in-chief was all but helpless to halt the human wave. Isolated border garrisons were pushed aside. Many surrendered immediately rather than face the gargantuan forces massed against them.

The first days of August saw vain delaying actions, as lone Austrian and German regiments attempted to distract STAVKA with pin-prick raids along the vast border. On 3rd August, Auffenberg led his Austrian 2nd Army, a hodgepodge of reservists, militia and soldiers rapidly transported from the Serbian front, against Meyendorf’s 5th Army, in an effort to save Tarnopol from encirclement. Russia’s first true battle of the Great War was a decisive victory. Outnumbering three to one, the Austrians were exposed on the flat Galician plains to massed artillery and flanking Cossack charges, forcing a rapid withdrawal. Confused by the simple sheer size of the Russian offensive, Hotzendorf gathered his forces where could, hoping to hold them at the much vaunted border fortresses. Informed by scouts of holes in the Austrian lines on 5th August, Grand Duke Nicholas ordered the cavalry to break off from his main force and punch through. Although reckless, the Russian commander-in-chief’s order paid off. On 10th August, a weary General von Irman led his vanguard into the streets of Lemberg which to his shock had been left undefended. Though not jubilant, the Polish and Ukrainian inhabitants welcomed the Russians to an open city.

The embarrassment of Lemberg was swiftly compounded. On the 12th General Belyaev’s 3rd Army pushed into Tarnow, while his scouts entered the suburbs of Cracow, only to be driven off by advancing German forces. The following day Brusilov declared Tarnopol his new headquarters having beaten a second delaying action led personally by Hotzendorf. Most shockingly however, was the fall of Przemysl the same day. The pride of Austria-Hungary’s Galician defences, Przemysl was an interconnected warren of trenches, barbed wire and bunkers designed to be the crux and command centre of any war against Russia. However the fortress maintained only a skeleton garrison in peacetime, as Vienna assumed they would have time to reinforce it before the arrival of enemy forces. Much of the perimeter unmanned, General Berkhman’s infantry poured in, capturing thousands of civilians yet to evacuate and many of Hotzendorf’s personal belongings. Indeed, the Austrian commander’s insistence on leading the defence of Tarnopol possibly saved him from capture at the fortress.

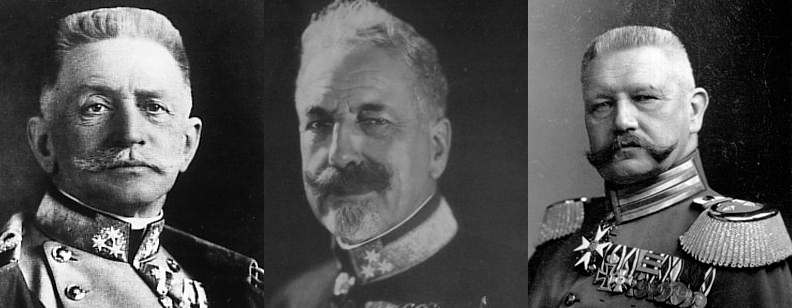

In little over two weeks, the Austrian position in Galicia had collapsed. Nicholas and Brusilov’s South-Western Front was almost at the Carpathians. In Budapest, the Hungarian Parliament rallied in anger and terror, with many convinced the Russians were only weeks from entering the city. In Vienna, the Emperor had been retired to bed on hearing of Przemysl’s fall, and his doctors called to administer a sedative. General Hotzendorf’s reputation as a commander had been shredded in only a matter of days. Although it is debatable how anyone else could have stopped the disaster, the fall of the ‘great fortress’ was a particular humiliation. Across the empire, people of all ranks were calling for his head, while messages were being passed through the German embassy, begging for help. Yet the Austrian Chief of Staff hung on. Ever persuasive, Hotzendorf convinced the Emperor via telephone and letter that he was needed to halt the Russians. In this he had the support of his former royal patron, Archduke Eugen.

Galicia after the Battle of Stanislawow. October 1914

Hotzendorf declared now that adequate forces were arriving at the front, he would stop Grand Duke Nicholas before he reached Stanislawow, the main gateway into Transylvania. By 20th August, Hotzendorf had assembled fourteen divisions to defend the city. Unlike in the frontier battles of the previous weeks, the Austrian’s had, numbers, terrain and, crucially, hundreds of new German machine guns to help in their defence. Meyendorf’s 5th Army began their attack on the 22nd, and quickly became bogged down. The Austrian trenches repulsed charge after charge, their machine guns and artillery causing devastation as the Russians marched in formation into the Carpathian foothills. By September the Austrian lines still held. Realising the Battle of Stanislawow could decide the entire Galician Campaign, both sides funnelled reinforcements into the meat grinder until 250,000 Austrians were facing off against 350,000 Russians. Despite terrible causalities, by the third week, Meyendorf, supported by Brusilov on his left flank and von Irman on his right, began pushing the Austrians back into the mountains. Suffering heavy losses themselves, and fearful of encirclement, Hotzendorf abandoned Stanislawow on 10th September, by now little more than a burning shell. Finally giving in to the by then unbearable pressure, Hotzendorf resigned at the beginning of October, to be replaced by Archduke Eugen, himself little more than a lieutenant to the recently shipped-in German General von Hindenburg.

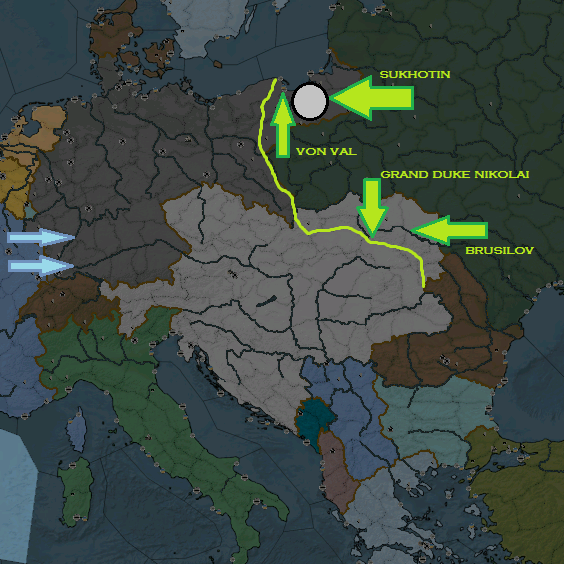

Equally as dramatic, the opening weeks in East Prussia were even more crucial the course of the conflict. Hours after Berlin’s declaration of war, General Mikhnevich’s 3rd Army marched virtually unopposed into Memel on the Baltic coast. The next day Marshal Sukhotin crossed the border, intent on cutting off the historic Prussian capital of Konigsberg before advancing onto Danzig. Initially, the Russian 1st and 2nd Armies, (some forty divisions) were opposed by only 70,000 Germans, commanded by General Sixt von Armin. This was due to Germany’s Schlieffen Plan, which proposed focusing the overwhelming majority of her forces against France in order to defeat her rapidly before turning attention to the Russians. However Russia’s rapid deployment was now causing chaos at German High Command. Despite Sixt von Armin’s successful delaying of Sukhotin at the First Battle of Allenstein in early August, the Kaiser and his commanders were horrified at the prospect of losing Konigsberg and feared a rapid march on Berlin by the Tsar’s armies. Soon two Armies, the entire strategic reserve plus precious forces from the Belgian advance were being transported across Germany to hold the line.

Commanders of the Austro-Hungarian Army: Hotzendorf, Archduke Eugen, Hindenburg

Despite overwhelming numbers, Sukhotin and General von Val struggled to pin down and out rightly defeat the smaller German army, amidst the marsh and woodlands of southern East Prussia. Every time the Russian generals focused their forces, Sixt von Armin was able to rapidly withdraw, only to attack his enemy from a new direction, often catching individual Russian columns on the march. Ironically it was the arrival of the western reinforcements in mid-August that doomed the German defence. Still outnumbered, Sixt von Armin was determined to keep his now 250,000-strong army together to provide an effective opponent. However now too unwieldy to maintain their hit and run tactics, by the 20th Sukhotin, supported by von Val and Mikhnevich (who had captured Tilsit several days previously), was able bring the Germans to battle. Outnumbering the enemy almost 2:1, the Russians broke Sixt von Armin at the Second Battle of Allenstein, seizing the town on the 28th and harrying the Germans towards Elbing.

The defeat only worsened the panic in Berlin, leading to yet more forces being redirected from the Western Front, where the advance had become bogged down on the outskirts of Brussels. At Elbing, General von Bulow now took command of the war in East Prussia. Much like at Stanislawow, the Battle of Elbing was a month long blood bath, as vast Russian formations bore down on heavily fortified defences. Even more so than in Galicia, the Tsar’s armies paid for every inch of ground with countless lives in what was the largest battle of the war so far. Nearly 600,000 Russians took part against 330,000 Germans. However eventually, despite a terrible cost, Sukhotin entered Elbing on 28th September. Only miles from Danzig and with Konigsberg and her 20,000 defenders now cut off, it was a major blow for German morale. However it had all but bled the North-West Front white. By the beginning of October, total Russian causalities in East Prussia and Galicia topped 350,000, while those left alive and uninjured were exhausted by two months of intense mobile warfare. Now, with Konigsberg threatened and Prussian honour sullied, the Russians would face the focus of the German war machine.

Second Battle of Allenstein. September 1914