Signs of growing German aggression

The new Nazi regime in Berlin sent a wave of uncertainty throughout Europe. After a decade of reconciliation and concord with the likes of Ebert and Stresemann, Hitler presented a starkly aggressive face for the German state, with clearly revanchist intentions. Germany’s withdrawal from the League of Nations in October 1933 was the first concrete sign of this new direction. For Italy, Austrian sovereignty was most significant, and it was Italy that pressed Britain and France into action on the issue. On February 17th 1934 the three nations issued a joint declaration that they had a common view of the necessity of maintaining Austria’s independence and integrity in accordance with the peace treaties of Versailles and Saint-Germain. Italy followed up the three power declaration with practical steps. On March 17th it entered into the Rome Protocols with Austria and Hungary, providing for a consultative pact. This was more than commerce; it was in effect a warning to Germany. On the following day Mussolini was more explicit. He proclaimed to Rome and the world that Austria could rely on Italy for the defence of its independence. Chancellor Dollfuss took this guarantee with gratitude and promptly tightened his grip. On May 1st, the paramilitary Heimwehr closed the

Nationalrat as Dollfuss announced a new authoritarian constitution. The governing right-wing coalition was officially merged into the Fatherland Front, establishing a one-party state to the detriment of the Social Democrats, Communists, and crucially, the Austrian Nazi Party [1].

By July, Berlin believed the window was closing on a moderately painless union with Austria. The domestic Nazi Party had been driven underground with thousands fleeing north to form the SS Austrian Legion [2], while hundreds more languished in Vienna gaols. Deciding desperate times called for desperate measures, Hitler sanctioned a putsch proposed by the Legion’s leader Theodor Habicht and the Bavarian state government. On July 25th Legionnaires disguised in Austrian military and police uniforms seized the RAVAG radio building in Vienna and announced the overthrow of Dollfuss and his government. Learning of the plot, the Chancellor suspended a cabinet meeting and, unsure how to act, remained in the Chancery. There the Nazis found him and shot him down. Despite their apparent victory, the Legion lacked major popular support and as isolated pockets rose up across the country, they were swiftly put down by the Heimwehr and Bundesheer under order from the newly appointed Chancellor, Kurt Schuschnigg. By the 27th violence had stopped and all the putschists were either imprisoned, executed or had fled. Some 240 people lay dead. All this horrified Europe, but none more so than Mussolini. The Italian leader had looked upon Dollfuss as a friend and protégé and decided to act immediately.

Mussolini ordered four divisions, 100,000 men it total, to the Austrian border to guard against any further ‘complications’. He telegraphed the Austrian Government to assure them that Italy would strenuously defend Vienna’s independence. On the 28th he broadcast to the world that Dollfuss’ killers had ‘suffered the wrath of the civilised world’. For several weeks the embassies of Europe were a flurry of activity as diplomats raced back and forth; it seemed war was inevitable. On 7th August, Prime Minister Mosley took it upon himself to fly to Rome in an attempt to avert conflict. By the end of the month Hitler had denounced German involvement as a rogue action by Habicht and the Austrian Legion was disbanded; the crisis quickly died down. Nonetheless, Mosley’s ‘summer jaunt’ (as some in the British press derisively dubbed the excursion) would prove of critical importance to future events. At the Palazzo Venezia, the Labour prime minister and the Fascist dictator kindled a life-long friendship, and began one of the most unlikely partnerships in 20th century diplomacy [3]. On the issue of Hitler however, there proved differences. Mosley attempted to explain German desires to undue the terms of Versailles, while tactfully accepting Mussolini’s interests in Austria, while Il Duce was far blunter; ‘Hitler will create an army’, he said, ‘Hitler will arm the Germans and make war… I cannot stand up to him alone. We must do something and we must do something quickly’ [4].

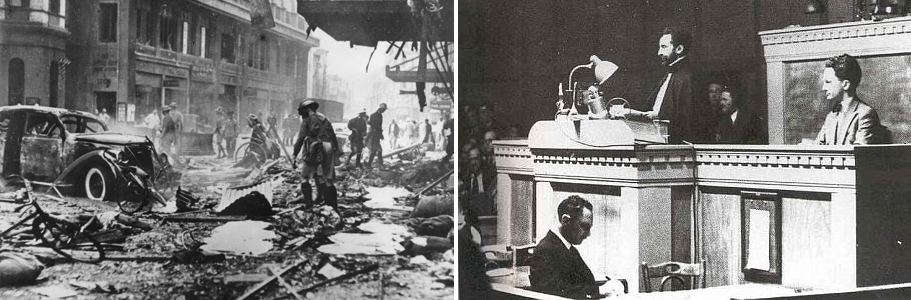

Austrian troops march through Vienna in the aftermath of the Putsch

The French proved more in step with the Italians than the British. Initially following the rise of Hitler, the French had been unsure how to react and had participated in the ultimately failed Four Power Pact of 1933 [5]. Led by their great elder statesman, Foreign Minister Louis Barthou, the failed Vienna Putsch produced a new focus in French diplomacy, namely the creation of an anti-German

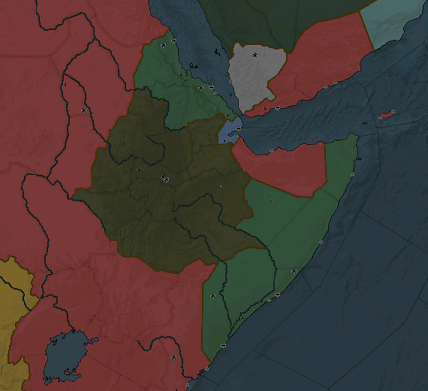

cordon sanitaire [6]. In January 1935, Barthou met with Mussolini in Rome. Alongside colonial matters in North and East Africa, the two men discussed Austria and the Rhineland, and the need for cooperation against Hitler. The discussions were marked by the extremely cordial relations between the two leaders, and on January 5th Barthou addressed Mussolini at a ceremony where the Italian dictator was presented the Legion of Honour; “You have written the fairest page in modern Italian history; you will bring assistance indispensable to maintaining peace”. Even better for Il Duce, Barthou left him with an unwritten guarantee of non-intervention on the issue of Abyssinia. That April, on the shores of Lake Como, the two men met once more, along with Oswald Mosley, to sign an official agreement reasserting a guarantee of Austrian independence. In private, Mussolini was able to gain an assurance of British discretion in East Africa as well. The meeting ended in good humour between all parties and despite the technical inaccuracy, most historians consider Como as the foundation of the Locarno bloc that would prove to dominate European diplomacy into the next decade [7].

Despite nods of consent from both Westminster and Paris, neither power seemed to be prepared for the swiftness of Italian action in Abyssinia in October. In reality, the invasion was the end result of increasingly violent border clashes stretching back to the first skirmish at Wal Wal the previous December. The French Government found itself under intense fire from the Left and anti-Italian circles as it stubbornly refused to take a stand on the issue. Mosley and Attlee on the other hand were somewhat blessed by the attention sapping headlines surrounding the King’s marriage crisis [8]. In the first days after the invasion, British representatives in Geneva were ordered to do everything they could to frustrate anti-Italian moves in the League of Nations, vetoing the League’s condemnation of Italy as the aggressor on October 7th and even putting forward proposals to legalise the invasion entirely under the anti-slavery protocols of Abyssinia’s accession agreement. While this move was narrowly rejected it left the League’s policy towards the conflict in utter disarray. By the time the war in Abyssinia reached the public consciousness, British policy on the issue had effectively created a fait accompli. The Government presented the invasion as a humanitarian intervention by Italy to prevent the slave trade and other barbarous practices and was to a certain extent successful, but nonetheless there was plenty of opposition to the conflict from a disparate range of groups.

(L) Addis Ababa in ruins following an air raid, (R) Haile Selassie puts his case before the League, December 1935

On October 31st George Lansbury spoke in Trafalgar Square to a crowd of almost ten thousand, marching in opposition to the war. In Parliament the Liberals were the first to come out against the Government’s position, quickly followed by some dissident members of the ILP. In mid-November Eden’s Conservatives followed, sensing that they had finally found a popular stance to take against a Government that increasingly looked like a shoe-in in the next Parliament. In the event however Labour’s early assumption of the moral high ground prevented a coherent opposition to Government policy, and the Abyssinia issue remained, as Churchill put it; ‘an issue in search of a crisis’. To Mussolini’s intense embarrassment, by the beginning of December the Italian advance in Abyssinia had begun to grind to a halt, slowed by the cautiousness of Marshal De Bono, logistical hitches, and continuous hit and run attacks on the overstretched columns. The easy campaign that looked all but assured a few months before now had the potential to be a draining struggle, even if there was little prospect of Italy suffering a repeat of the humiliation she suffered at Adowa forty years before. With this in mind Mussolini sent quiet feelers to both Paris and London indicating his willingness to come to a compromise peace. Mussolini’s action came as a huge relief to the Laval Government in France.

In early December the French entered into consultations with the Mosley Government in Britain, and on the 8th Barthou and the British Foreign Secretary Clement Attlee both flew to Rome to put a compromise peace to Mussolini. Under the terms of the proposal, Abyssinia would be dismembered. Italy would gain the best parts of Ogaden and Tigre, and economic influence over all the southern part of Abyssinia. In compensation, Abyssinia itself would have a guaranteed corridor to the sea, by acquiring the port of Assab from Italian Eritrea. The rump of Abyssinia would become a semi-autonomous region under the trusteeship of the League, although in reality this was intended to formalise British and French influence over the remains of the region. Thanks to British and French intervention, on the 21st December 1935 the brief conflict in Abyssinia came to an end through a cease-fire. The following day the League retroactively legitimised the invasion by accepting the responsibilities offered to it in the region and realising that the deal was their only chance of independence Emperor Haile Selassie signed the treaty on Christmas day. The Mosley Government’s secret diplomacy on the Abyssinia issue took the war’s critics by surprise, and when Mussolini announced that he was submitting to Anglo-French mediation on December 9th Mosley pulled off a public relations coup. Mosley’s insistence on the League’s involvement satisfied the internationalist wings of both the Labour and Conservative parties, and while the reduction of Abyssinia to a rump appalled some on the anti-colonialist left, the Government was able to claim that it was the best possible deal that could be made to save the nation from complete destruction [9].

The Christmas Resolution

----------------------

[1] All OTL

[2] Despite the name, more of a ramshackle terrorist group than a military unit.

[3] Mussolini and Mosley hit if off IOTL too.

[4] He said this IOTL as well, in the early 1930s Mussolini made a point of being Hitler’s nemesis.

[5] An effort by Mussolini to replace multilateralism in Europe with realpolitik dominated by Britain, France, Italy and Germany. Just as IOTL the powers were unsure of each other and the watered down final agreement achieved little.

[6] Due to butterflies the assassination attempt on Alexander of Yugoslavia isn’t carried out, sparing the King and Barthou as well.

[7] The Locarno Treaty was the earliest and best known tripartite effort to keep watch of Germany. As such by popular memory and media inconsistency TTL’s Stresa Front will be known as the Locarno Powers or bloc even though Como is where the real groundwork of the alliance is laid.

[8] More on this next time.

[9] The difference between this and the hated Hoare-Laval Pact of OTL? Well the Government is able to grab the moral high ground early on and the inclusion of a League mandate wins over a lot of internationalists, while Barthou has provided some solid political saavy to get many League members on side. Also the plan is never leaked meaning it is presented as a done deal before any critics can put the boot in.