Prologue

The Turnismo

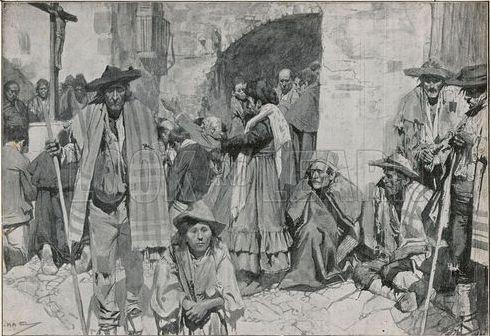

Allegory of the short-lived First Spanish Republic

The first republican experience of Spain was a very short and unstable one. In February 11, 1873, after the revolt of the army artillery corps and the subsequent Hidalgo Affair, the short reign of Amadeo I came to an end when, after the king’s abdication, the parliament declared the First Spanish Republic. However, serious internal problems like the Third Carlist War, the Cantonal Revolution and the Ten Year’s War in Cuba, together with the lack of support from the military officers led to a quick end of the republic. In 1874, less than two years after the beginning of the republic, the pronunciamento of General Martínez Campos in favor of the restoration to the throne of the Bourbon monarchy was the final straw, and in December 29, Alfonso XII was crowned King of Spain. Thus began the Restoration period.

Arsenio Martínez-Campos and the restored king, Alfonso XII

The restoration period began in Spain after almost a century of political instability and civil wars that made the country lose most of his massive colonial empire and lag even more behind the major European powers of the time, so it had the primary objective of achieving internal stability. This was accomplished using a system which received the name of Turnismo. It was the deliberate rotation of the Liberal and Conservative parties in the government, using massive electoral fraud, so no sector of the bourgeoisie felt isolated, and excluded all other parties from the scheme.

This system initially fulfilled its main objectives, and so Spain entered a time of prosperity not seen since the Age of Discoveries. These years were marked by large economic progress, and the national industry grew fast and strong due to harsh protectionist measures. It was a time of widespread and profound modernization of the country, and Spain managed to partially make up for the lost time.

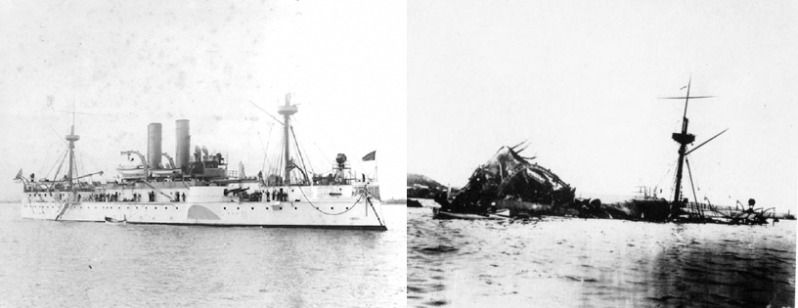

The USS Maine and its wreckage in the harbor of Havana

Fortunes began to change, however, when the USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor, taking the lives of 266 American sailors. Spain was already having problems with the Cuban rebels yet again since 1895, and US pressure for the independence of the island was mounting. The American media soon started to foster popular opinion into demanding a swift belligerent response. Spain refused an American ultimatum to leave Cuba on April 21, and the US Navy started a blockade of the island the same day. War was now inevitable, and Spain, against all odds, declared it on April 23.

The destruction of the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay

The Spanish-American War, lasting not even four months in 1898, was a short and bloody one. Spanish forces were pushed back on all fronts, and the American forces soon conquered Guam and Puerto Rico, and effectively assisted the Cuban and Filipino rebels in expelling the Spaniards. Defeated in all fronts and with its fleet in disarray, Spain sued for peace, and hostilities were halted in the twelfth of August.

The Treaty of Paris, signed in December 10, 1898, was a humiliation for Spain. The agreement gave control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, parts of the West Indies, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States in exchange for a payment of twenty million dollars. The once mighty Spanish colonial empire was now confined to a few remaining possessions in the western coast of Africa, and the nation was completely humiliated.

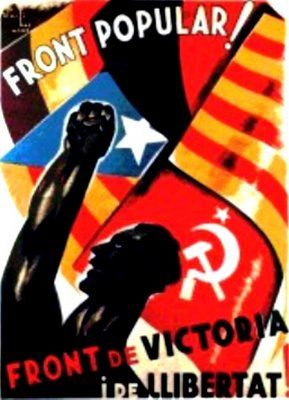

Stripped of its rich colonies and politically and military disgraced, the situation of Spain took a sharp turn downwards. With the government credibility undermined, the Turnismo was nearly overthrown when General Camilo de Polavieja tried, but failed to take power, and however this was not the end of the Spanish domestic problems. Aiming to regain its international prestige, Spain started a conflict with the Berber tribes of the Rif, in Morocco, but met stiff resistance and the need for recruitment and shipment of troops increased dramatically. This led to increasing social unrest, which culminated in what is known as la Semana Trágica, when, in the last week of July 1909, the working classes of Barcelona, incited by anarchists, socialists and republicans, rose in revolt against the conscription of troops to fight in the 2nd Melillan Campaign. Martial law was soon declared in the city, and a week of clashes between the militia and the Guardia Civil caused a bloodbath, with dozens dying and hundreds arrested, including the anarchist Francesc Ferrer, who was later executed by firing squad, until order was restored on August 2. The socialist UGT and the anarchist CNT unions attempted to initiate a general strike across the country to spread the revolt, but ultimately failed.

Remains of a Spanish garrison after the Disaster of Annual

The Spanish government opted to remain neutral throughout the Great War, and this most certainly contributed to delay the fall of the Turnismo, since Spain was by all means not fit for war, but the political rotation system, in power since 1874, was already obsolete and doomed. The Rif War started in 1920 when General Dámaso Berenguer decided to expand the Spanish exclave in Morocco. He advanced against the eastern territory, controlled by the Jibala tribes, but met little success, facing stiff resistance from the skilled Berber leader Abd el-Krim. The Spanish efforts culminated with disaster in the Battle of Annual, where el-Krim inflicted in them one of the worst defeats in the history of colonial wars, killing 8.000 Spanish soldiers and officers. By late August 1921, all the territories Spain had gained in Morocco since 1909 had been lost, and Melilla was only spared because the Berber leader feared intervention from other, stronger European powers would happen if he took the city. Spanish fortunes in the Rif did not improve, and the government, already discredited, had to blame someone for yet another failure, and the Armed Forces were chosen as the scapegoat. The military top officers felt cheated, because they were ordered to move into the desert without proper supplies and equipment, and a feud, after years of growing disagreement, began between the parliamentary government and the military.

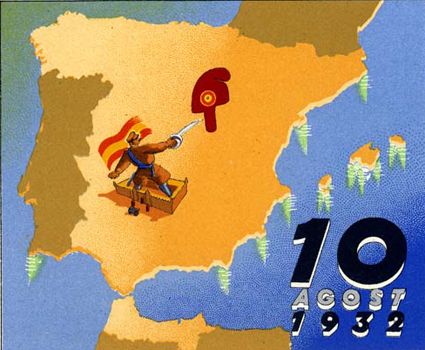

Coupists announcing the new government to a crowd in Madrid

The military discontent, the fear of anarchist terrorism or a proletarian revolution, and the rise of nationalism ended up causing great agitation amongst the civilians and the military. It culminated on September 13, 1923, when Miguel Primo de Rivera, Captain General of Catalonia, with support from the military leadership, which was inspired by Italian Fascism and Mussolini’s March on Rome, emitted a manifesto blaming the problems of Spain on the parliamentary system. Just as it happened in Italy with Vittorio Emanuele III, Alfonso XIII, probably seeing the coup would go ahead with or without his support, backed Primo de Rivera, and nominated him prime minister. His rise to power as de facto dictator of Spain ended the Turno system of alternating parties.