I was a fan of Lords of Prussia and your French sequel is just as good if not even better. I love a nice in depth history book AAR. Early Modern Europe is a weak point for my historical knowledge so EU3 has never garnered my interest unless done nice and juicy like LoP or Milites' efforts. Very nice. Very much subscribed.

Lords of France: Roads to the Enlightenment

- Thread starter Merrick Chance'

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Lords of France

Consolidation, part two: Successes, chapter 2

Jean des Ursins, widely known as d'Ursine (the Bear) for his stubborn personality, continued the policies of Charles VII for a decade after his death

Consolidation, part two: Successes, chapter 2

Jean des Ursins, widely known as d'Ursine (the Bear) for his stubborn personality, continued the policies of Charles VII for a decade after his death

Unlike the upbringing of de Villenueve, Jean des Ursine spent nearly all of his life in the service of the French crown, and his time as the head of the diplomatic corps spanned through the reigns of Charles VI, Charles VII, and Francois I. This is because--again unlike de Villenueve--d'Ursine came from the north of France, and was the son of the incipient urban nobility.

Unlike the rebellious southern aristocrats, France's northern nobility had lived through the horrors of the 100 Years War and had seen the dangers of a France lacking in a strong central authority. And so, when des Ursins turned 18 he joined the French diplomatic corps and was stationed in the Holy Roman Empire. He earned the moniker 'The Bear' during his time as the ambassador to Cologne. In the election for who would be the elderman for the Hansa, only one of the candidates, Franz Schulz, was pro-French. Des Ursins took it upon himself to make sure that Schulz won the election, caring not that Schulz had little chances. He used spies, assassins, thieves, and agent provocateurs to ruin the reputations and lives of Schulz's opponents. Eventually the only two candidates were Schulz and a man named Freidrich Klein. Klein was far less popular among the town elders, but far richer. Des Ursins responded to this by ordering the burning of the Klein counting house, which absolutely destroyed Klein's wealth and led to a Francofile in the Hansa's governing structure. When Charles VI asked why Des Ursins went so far, and used so much French coin, in an operation which could have angered the Hansa and the Emperor. Des Ursins' response gave him his name and left such a strong impression that he became the head of France's diplomatic corps:

"I felt that it was necessary. If I felt that burning down the City was necessary, I would have done so."

The burning of the Klein counting house would become one of the origins myths of German nationalism, but D'Ursine's involvement in it was not verified until the 1700s

This incident gives us a great view into D'Ursine's personality: like de Villenueve and Charles VII, he had an immensely aggressive personality and a deep willingness to do whatever he felt was necessary. However, he shared Charles' pseudo-idealism and worried about what the side effects of Francois' unilateralism would be. It was lucky for D'Ursine, then, that Francois believed in D'Ursine's abilities and was willing to simply outlive him. This trust of D'Ursine's abilities was makes sense, given his several successes in the period, the first of which happened before Francois' coronation.

The anti-piracy force and the French military access pact

Henry VI opened a massive pandora's box when he started his aggressive piracy campaign against France. The profits gained by the privateers ended up being self-sustaining and privateer companies multiplied across first the Norman Coast and soon became a threat across the whole European Atlantic Coast. This led to an international problem which became worse after the beginnings of colonization, but more directly, it effected the French government's authority across the coast and, more directly, in the Duchy of Provence and the County of Armagnac.

This problem became far worse with the resurgence of the Barbary pirates in 1457. Fishing towns all along the Mediterranean were destroyed, the profitable Italian trade disrupted, and the Wine Orchards which dotted the French Mediterranean suddenly found themselves much poorer. This problem required action by Charles VII but also provided a major opportunity: a joint anti-piracy force could act as a support for French unity, and could show the unfaithful southern vassals a reason to support the French crown.

What followed was the kind of policy typical of Charles VII and d'Ursine: it brought the French crown the greatest power while keeping essentially keeping the status quo, it was drawn up by a pair of strategists who played a patient game. It was also the kind of policy which Francois looked at down the curve of his nose, though he didn't see it as actively dangerous: to Francois such a 'soft' policy essentially gained nothing and lost nothing.

The young Barbarossa, Scourge of the Mediterranean, actually participated in the attack which would create one of the strongest anti-piracy forces in the Sea. The ships (likely under the pay of the Mameluke Sultan or the Turkish Padishah) attacked and destroyed Sete, a fishing and wine town close to Montpellier. When the survivors of the attack came to Paris to voice their concerns, they were surprised that plans for a long-term and far reaching anti-piracy policy were already underway. The Anti-Piracy Force would include ships, inspectors, and personnel from all over the Kingdom, involve treaties which erased borders within the area which the Conseil deigned to call Greater France, and (and this was the icing on the cake), Sete would be rebuilt and made the center of the Mediterranean anti-piracy efforts.

The Greater France anti-piracy force would involve sailors and policemen from all over the French kingdom, as well as Burgundan sailors

The one issue which Francois had with the policy was d'Ursine's plan to use the military pact in order to entrap Burgundy. It was agreed by both the Charlesians and the Francoisi that Charles I of Burgundy had been acting far more aggressively as of late: he had allied with the Duke of Brittany in order to block that route of French expansion and had married one of his younger daughters to the Prince of Burgundy the Comte* d'Anjou. The way these two factions responded to cautious if clear Burgundan aggression differed greatly: d'Ursine and Charles VII sought to bring Burgundy farther and farther into the French fold, making actual aggression impossible (or at least obvious). Francois I planned on undermining Burgundy through counter-alliances. Just such a counter-alliance is the subject of the next major French diplomatic success of the era.

The Franco-Hapsburg Alliance

August I, the Holy Roman Emperor who (temporarily) ended the several-centuries old rivalry between Germany and France

I said earlier that Francois' untrusting and psychologically unilateralist thinking drove him to seek a farther ally, one who would give less security but would also weaken him less in the case of a betrayal, and one who would counteract the possibility of a Burgundan betrayal. As such, the first meeting he had with his Conseil was on the topic of allies that France could seek to counterbalance Burgundy. Two such allies came to mind for the Conseil: Bonde Sweden, and Hapsburg Austria.

Francois saw an alliance with the Hapsburgs as the easiest way to undermine Burgundy's attempt at a royal title: if he could make Burgundy look less like a potential rival to Germany's enemy France and more like a belligerent and aggressive power encroaching on Imperial territory. Luckily, the Austrians were already convinced that the Duchy had to go, after the Duchy's deftly made personal Union with the Duchy of Milan and her wars of aggression against the poorly led Dutch league (consisting of the Bishopric of Utrecht and the Counties of Gelre and Freisland). And seeing that the king Francois had been a good friend of Emperor August (and his son, Maximilian), the alliance was soon signed.

The alliance was soon sidetracked by the Turkish threat. The Ottoman Empire declared war upon the Kingdom of Hungary in 1460, which left the Emperor in a conundrum: he had a smaller army than both the Ottomans and the Duchy of Burgundy, and if he were to send his army against the Turks and, against all odds, win, he would leave himself open to destruction at the hand of the Burgundans.

The Emperor got around this problem by launching a war against the minor Christian states in order to cut Turkish supply lines and counterbalance any possible Turkish gains in Hungary. And, in order to make sure that the French government was making good on her alliance, he called her armies to arms.

Austria's war against Montenegro, Bosnia, and Serbia

Apologies for the incomplete entry. I'm probably going to compete this entry soon [IE tomorrow] and complete an entry on Francois' domestic successes to 1470 within the week.

*Comte is French for Count, similar to how Marquis is French for Mark or Margrave

Love the indepth reporting.

Have read several books on 100 year war from the english perspective.

Have read several books on 100 year war from the english perspective.

Lords of France

The General Estates Meeting of 1468

The General Estates Meeting of 1468

While Francois sent military advisers to what would be called the 1st War of Haemus (Haemus being the name of the region until the Turks renamed if after the Balkan woods. Note that in my first playthrough I saw Francois' low diplomacy meaning that he was headstrong, now I see it more as him being a complete curmudgeon and a hard man to like. Ergo I didn't send the Royal Army to fight in the War, which was all for the better because it came to nothing on both sides), most of the Valois court's focus was directed at another military issue: the issue being the defense of France herself.

The Report to the French king on the state of the militaries of France's rivals. The size of 'China's army is likely an approximation.

This issue presented itself at the beginning of 1464, when the Status of the Realm Report which Francois commissioned of D'Ursine was finished. It showed that while France was one of the richest kingdoms in the known world, alongside Castille and the Ottoman Empire, her army was sorely outsized by the Duke of Burgundy's army, as well as his new ally, the King of Aragon. This was made worse by the fact that, while the 45,000 man Army of Burgundy was controlled directly by Duke Louis, and while the 25,000 man army of Aragon was controlled by the Aragonese king, France's 54,000 man army was split between her and her vassals, with Francois only controlling half of his actual army.

The state of affairs of the French military. Note that, while the Burgandian* army was less well trained than any of the armies of France, her size and the fact that her troops were right at the gates of Paris severly limited French freedom of action

Thus, France's military problems were tightly tied up in her governance problems: she ruled over vassals which did not particularly like her, and any move on her part to centralize went against both the traditionalist factions in French politics but also the interests of the vassals themselves. It is here where Francois' caustic personality helped him a great deal: while his father was a feudalist at heart, and tempered his aggressive policies with a sincere belief in the ideology of feudalism. Francois was not constrained by such a belief: he was an administrator at heart and saw the constraints placed on him by his vassals just as they were: constraints. With this, we can say that Francois may not have been a king of modern France, but he was France's first modern king.

We can say that the story of Francois I's reign is one of centralizing authority. A series of events led to the passing of the Milice Acts across the country, a series of events characterized by Francois using all of the Medieval tools at his command to craft something similar to a modern state. Three major events, involving 3 major premodern institutions, led to the creation of France's modern military.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/88/Galileo_facing_the_Roman_Inquisition.jpg

The Swiss guard proved to be the first catalyst in a widespread reformation of the French army

The Swiss guard proved to be the first catalyst in a widespread reformation of the French army

The first step towards the kind of army prescribed in On Command required a massive reformation of the French army. De Villenueve did this by finishing the process he started in 1453: now, instead of mercenaries being inducted to the French army, de Villenueve started hiring mercenaries as instructors in the modern warfare tactics discovered in Italy and Switzerland.

As I said earlier, the strategy of On Command called for a defensive mode of warfare which would be augmented by an informational advantage created by light cavalry. This required a French military was more focused on light cavalry and heavy/ranged infantry as well as more officers. De Villenueve went to foreign lands for these new combat methodologies, but he stayed at home when recruiting officers.

The Swiss Guards, who are now known as the troops who guard the Pope, were in the 15th century the most elite soldiers in Europe as well as the most doctrinally advanced. The Schweitzergarde's use of pike square formations led to decisive victories against larger and better equipped foes again and again, most crucially in the Battle of Bern, in which Swiss mercenaries repelled a large force of Burgundan knights. The news of this battle deeply intrigued de Villenueve: if the well trained Swiss army could fight off the larger, albeit untrained, Army of Burgundy, then a French army utilizing similar strategies should be able to fight off the Burgundian army, and, almost as importantly, enforce Valois hegemony over the Kingdom of France**.

This occurred in parallel to a massive upsizing of the army. Francois had realized by this point, given the fast popularity of the Army Academy, that the best way to curry favor with the high lords*** and low lords of France would be to focus on the things that the Valois court was uniquely able to provide: the most important of these being military force. Increasing the size and abilities of the Valois military meant that

- The vassals, instead of being a possible threat (especially with news that the Duke of Provence wanted to ferment a rebellion), would now be totally in the sphere of Valois France

- The Duchy of Burgundy would be far less off a threat

- More of the French aristocracy would be involved in the military, and thus reliant on the government.

But how were these 8,000 new troops, as well as the rest of France's 30,000 man regular army, retrained? Shortly after news of the Battle of Bern, de Villenueve contacted the Stadtholder of the Bern canton about hiring a battalion of the Swiss guard to serve both as the Royal Guard for Francois I, but also in a training role. Although doing this led to the Treaty of Bern, in which France recognized and guaranteed the independence against any possible attackers, the benefit was unparallel. The French Royal Guard served primarily in the French Army Academy at Othe, training the French military in the methods of pike warfare. This allowed for a reformation of the French infantry, but how were the cavalry retrained?

The French Royal Guard was used primarily as a training force, teaching the new generation of French officers and soldiers the strategies of pike warfare

In de Villenueve's theoretical universe, a focus on defensive and heavy infantry wasn't enough: if the French army was focused entirely on heavy infantry and heavy cavalry, then she would be in a losing proposition: heavy cavalry were simply not fast enough for the kind of constant scouting/raiding operations that de Villenueve saw as necessary. Thus, a heavy/heavy army would lose the information advantage and thus the reactive abilities conferred upon the defensive. So clearly, a reformation of the French cavalry was required as well.

De Villenueve performed this reformation in two ways: by bringing the veterans of the Invasion of England back to France and promoting them to officers, and by hiring officers from his mercenary days, again as training officers. This was a political masterstroke--although transitioning from heavy to light cavalry posed the threat of an outcry connected to the image of the French knight, the Raiders of England were seen as the soldiers who helped end the 100 Years War, and had massive prestige. The Reformation of the French military had begun.

The possible outcry from a switch to chevauchee light cavalry was ameliorated by the prestige of the Raiders of England

The Reformation of France's military was a tremendous success: it produced Europe's first modern army, which wasn't reliant on mercenary soldiers or peasant levies. It increased the ability of the Army Academy to act as a unifying force within the Valois territories, and it enacted in practice what de Villenueve had been arguing for in theory. Lastly, it produced perhaps the most advanced army at the time, which served in several wars through the 1470s and brought great prestige to France and the Valois name.

The start of the Reformation of the French military in 1466, and its results in 1470, just in time for a decade of wars.

The French Inquisition

The Trail of Gallilaeo Gallili is one of the most famous events involving the Inquisition. However, the Inquisition was used differently in different contexts and was generally used against the peasantry.

Even with the reformation of the French military, the French provinces were still a patchwork. In the Early Modern period, France (as well as most other 'countries') had little common culture, barely had a common law, and barely had a common language. The Occitan Language (or Langue D'Oc) and the Provencal Language both competed with Cosmopolitan French through the early modern period. Furthermore, throughout the Occitan and Provencal regions of France, the Cathar heresy was still strong, which deeply undermined Valois authority in the provinces. Francois I saw all of these administrative deficiencies as problems to be dealt with aggressively and swiftly (Although I haven't explicitly said it, Francois I was deeply influenced by On Command and saw the administrative and cultural problems of France, as well as the enemies of France, as variables to be controlled rather than as, well, people[/color), and he attacked these deficiencies by creating the feared French Inquisition. In balance, Francois I's reputation as a tyrant probably has most to do with this institution, which ruined the lives of so many Hugenots.

France has historically been one of the largest players in Papal Politics, along with the Holy Roman Emperor. The Reconquista provided a rival power, however, a rival who would soon become one of the biggest forces in Catholicism: the Kingdom of Castille. The death of Pope Leo XI led to the election of the Archbishop of Almeria (Pious VII), a zealous man who had started out as a Chaplain for the King's Royal Guard. During his time by the King's side, he became a fierce proponent for the recreation of a Spanish Inquisition to administer the newly Christian Duchy of Granada (I don't know about DW, but in MMP2 Castille/Spain has a bad habit of vassalizing Granada rather than taking anything. Then they start loving them, except they can't diploannex them). Because of his success in converting the city of Huesca and his critical role in the creation of the Castillan Inquisition, he was put in charge of the Granadan Inquisition.

After a highly successful career in the Granadan Inquisition, he was made a Cardinal in 1464. This put him in a perfect place to become Pope with the death of Leo XI. Unlike the Humanism of Leo XI, Pious VI's reign led to widespread adoption of Inquisitorial methods throughout Europe. These Inquisitions were set up for different reasons in different countries: in Granada and Lithuania, the Inquisition was legitimately used in the fashion that Pious VI probably intended: as a force against heresy so widespread that it threatened the very existence of these states. But in Austria, England, and France, the Inquisition simply turned into the private security force of the state, attacking dissent and cultural minorities.

Francois I made plans to adopt an inquisition under Papal pressure in the early 1460s, but it was only after seeing its implementation in Austria that he was fully converted to the concept: he was especially interested in the hierarchy between the Austrian and Hungarian Inquisitions, through which the Austrian Arch-Duchy exerted control over the people of Hungary. He saw the adoption of an Inquisition in the same light as he saw the expansion of the army: as a way to exert control over the provinces as well as over his vassals. But he went farther than Maximillian: the tendency in Austria to use the Inquisition mainly for petty repression was repeated and magnified within Northern France, where Francois used them against tax evaders and rebellious local aristocrats (The effects of this repression I will get into in the next section[/gold]). In Southern France, however, they were used to combat the Cathar heresy and actually did put an end to the sect within a year.

This led to contrary effects in Southern and Northern France: in Northern France the Inquisition enforced, above all, incest laws, which broke up the institution of the family-run plantation. In the South, however, the Inquisition attacked the Cathar heresy, a Gnostic-inspired sect started in the 12th century. Because the Cathars were found primarily in the cities, the Inquisition sought the support of the nobility, going so far to as to abolish the autonomy of several cities (breaking a tradition that had lasted centuries). But in both the North and the South, the effect was the same: the French Aristocracy was subjugated under the thumb of the government: in the north through force, and in the south through surrender.

Note that I also got +1 centralization and +1 aristocracy from the decision

The General Estates Meeting and the Milice Act

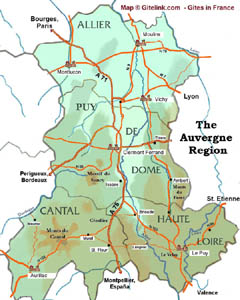

This all led to a strikingly different situation from the last General Estates meeting. The Estates meeting of 1458 required a massive military victory for Charles VII to assert even a basic amount of control. In 1468, Francois had won no war, fought no battle, and yet he was entering the newly constructed parliament in Auverne in a far better position than his father had ever been. He was now in charge of an actualized and centralized state, his army was stronger than all of his vassals combined, and the French Inquisitions were firmly under the control of Ile de France.

Better yet, the Academy of the Army of France had proved immensely popular with the sons of the French high-lords. Not only was it likely the best educational institution in France outside of the Parisian University, it was at the head of the dynamic and prestigious French Army, and it allowed a fast track for an important governmental position. So Francois I could leverage the popularity of the Academy in order to subjugate his vassals further. The Milice Acts, of which we have drafts dating back to before the reformation of the French Army, put the French King in control of all of the militaries of the French kingdom, including city garrisons, anti-piracy forces, and most importantly, the armies and navies of her vassals. These acts were the sole focus of Francois when it came to the

Although Francois assigned d'Ursine to arranging the Estates meeting through most of the 1460s, d'Ursine was, simply, not interested. Unlike de Villenueve, who was a reformer at heart, d'Ursine saw Francois' actions as foolhardy, arrogant, and generally bad for the Kingdom. So, with each assignment given, d'Ursine reminded Francois that the Cabinet members had almost total autonomy and that if the King wanted a more compliant ambassador he would have to fire his current one. This led to several yelling matches but little actual action. It also almost led to the death of the King's precious legislation.

The very first point of discussion in the General Estates was brought up by the Duke of Bourbon, on the subject of the economic security of the realm (This relates to a failure on Charles VII's part, which I will get to in the next section). Although Francois had planned for this section to last merely a day, the Duke of Bourbon as well as the Counts of Armagnac and Foix kept a discussion going about the failure of the Valois government to bring any of the riches attained in the last, expensive stretch of the 100 Years War to the vassals, and demanded that the King recognize not only the political but also the economic independence of his vassals, and back this recognition up with a yearly subsidy.

The King would have none of this. He was barely able to pay for the Kingdom's yearly expenses plus the cost of the newly expanded bureaucracy and military anyway, and the costs asked of the subsidy would break him. But he didn't know when the next Estates meeting would be: that meeting may have been his only chance to adopt the Milice Act.

It was after a week and a half of discussion on economic topics that Francois decided to veto the legislation crafted to that time. This provoked an outroar, with the Duke of Provence nearly shouting down his King. Francois, never a man for diplomatic speeches, was nearly boiling over with rage at being treated as an inferior, and the parliament would have gotten ugly if it weren't for the sudden and unexpected intervention of d'Ursine.

D'Ursine argued that the largest expense that most of the vassals had was the expense accrued by their armies. This was deficient: the amount of actual force added by these small corpses barely brought any real security to the vassals, even as they were nearly bankrupted by the costs of these 4,000 man armies. It made the most sense, since the French government had the largest military infrastructure, to delegate the duties of protecting the realm to the King. "But who will protect us from the King?" asked the Duke of Bourbon. Well, responded d'Ursine, none of the vassals could scarcely defend themselves now if the King were to threaten their realms. The levies used by most of the vassals (with the exception of the troops of the County of Foix) couldn't even defeat the Valois army one on one, let alone outnumbered.

And it was with this point that Francois laid the last stroke: he laid down the basics of his Milice Act, with a sold addendum: that the sons of any of the French Highlords would be given free admission to the Academy of the French Army, and guaranteed a higher level position. The proposition was met with widespread applause; the Militia Acts were passed and they were a success both in the short run and the long run. In the short run, the General Estates meeting of 1468 left France in with a larger state than ever before, and it left a huge and immensely competent French army to deal with the wars of the 1470s. But that wasn't all: in the long run, the Academy would indoctrinate the future generations of High Lords.

The effects of the General Estates Meeting of 1468

*Jesus god I just now realized that Burgundian was the right demonym for person living in Burgundy. So sorry!

**With the estates meeting happening, names may start getting confusing. Right now (until a point that will come very soon) when I say "The Kingdom of France" I mean France and her vassals. When I say "the French government", "the Valois court", or use the term France when talking about the relations between the Valois court and some other foreign government I mean the country France sans her vassals.

***IE the French vassals and the various counts in Southern France

Responding to people/Reading List entry

The early modern period is...weird, to say the least. What's mostly taught to high schoolers is that the Reformation and colonization happened during it, but there's so much more. The period interests me more as a social scientist than as a historian: you have all these societies stumbling towards something like modernity. Thank you for your support!

I agree with you about the 'bigness' of France. The issue, as I said, is that most people play AARs as hyper-rational, all seeing gods rather than as the rulers of actual countries. Historically, France was in kind of the same position as Ming: she had a ton of potential power but couldn't use it because her governance structure was a mess. EU3 (up until DW) does a poor job of simulating such a structure, but I'm trying to create it.

And now, the reading list! It's been commented multiple times in Lords of Prussia and Lords of France that I 'write like a real historian' or something similar. This partially has to do with the major in history/polisci I just completed, but moreso has to do with the kinds of books I read: since '08 I've pretty much only read History and Social Science books. In the cases of AARs, this gives me an advantage: histories tell me what did happen during the period, and give me a sense of what's plausible during this period. Social science books tell me how the structures I'm talking about act in general, which lets me fill in the gaps once I go too far off the historical rails. So here are the books I've been reading for this AAR:

General French Histories

I was a fan of Lords of Prussia and your French sequel is just as good if not even better. I love a nice in depth history book AAR. Early Modern Europe is a weak point for my historical knowledge so EU3 has never garnered my interest unless done nice and juicy like LoP or Milites' efforts. Very nice. Very much subscribed.

The early modern period is...weird, to say the least. What's mostly taught to high schoolers is that the Reformation and colonization happened during it, but there's so much more. The period interests me more as a social scientist than as a historian: you have all these societies stumbling towards something like modernity. Thank you for your support!

This is a fantastic AAR. Usually I scroll over France AARs because I "There big and powerful, and most likely boring", but I saw MM. I liked it so much I'm going to go read lords of Prussia

I agree with you about the 'bigness' of France. The issue, as I said, is that most people play AARs as hyper-rational, all seeing gods rather than as the rulers of actual countries. Historically, France was in kind of the same position as Ming: she had a ton of potential power but couldn't use it because her governance structure was a mess. EU3 (up until DW) does a poor job of simulating such a structure, but I'm trying to create it.

And now, the reading list! It's been commented multiple times in Lords of Prussia and Lords of France that I 'write like a real historian' or something similar. This partially has to do with the major in history/polisci I just completed, but moreso has to do with the kinds of books I read: since '08 I've pretty much only read History and Social Science books. In the cases of AARs, this gives me an advantage: histories tell me what did happen during the period, and give me a sense of what's plausible during this period. Social science books tell me how the structures I'm talking about act in general, which lets me fill in the gaps once I go too far off the historical rails. So here are the books I've been reading for this AAR:

General French Histories

- L'Ancien Regime by Franz Funck-Bretano. Written in the 20s, this is one of the older 20th century histories of the period. Unfortunately there's a reason that it's such an obscure text now: Funck-Bretano had an unabashed love for feudalism, and it comes through in a lot of his writing. However, since I'm lacking in a general history of France through the whole early-modern period, I'm defaulting to this as well as another small book called

- History of France by de Sauvigny and Pinkney. Unfortunately this text is perfect for me: no clear ideological bias, just the facts, but it's short as hell for the period it has to deal with and isn't helpful for much other than gathering names.

- The Origins of Political Order by Francis Fukuyama. An instant classic on political development, his section on the rent seeking French nobleman is going to be a huge help when I get fully into the early modern era

- Bureaucracy by James Q. Wilson. Another great book on its topic, Wilson argues in it that the so called 'pathologies' of bureaucracy aren't really pathologies at all, rather they are a product of bureaucratic institutions having different motivations than, for instance, firms.

- Decoding Clausewitz by Jon Sumida. A great book on the subject, I'd recommend to anyone interested in the topic.

- The Sun King by Philip Mansel. A short little book on the relationship between Louis XIV and Versailles, this won't come up until later (I hope to skim over the Reformation since it won't direct effect France, in order to get to the period after the 30 Years War)

- When the World spoke French by Marc Fumioldi. A pretty interesting intellectual history of the French Enlightenment through the eyes of foreigners. Probably better in the original French, too much of the floweryness of French academic prose comes through and I'm not a fan of that style.

Last edited:

You=Winning

=D

thanks!

Sorry for the gap in entries, I've been unmotivated since the "Sad State of Affairs", and furthermore the autosave function has eaten my (NEARLY FULL AGGGH) post twice. By this point it's been nearly 2 weeks since I played the section I'm writing on, so I'm going to

The great failure of the transition period

Those who are experts on French royal history will note that my depiction of Francois I doesn't meet with his traditional portrayal. Francois the Tyrant, as was his moniker after the early 16th century, exists in French history as a specter similar to Henry VIII or Ivan the Terrible exist in English and Russian histories: he was a wildly authoritarian force within the Kingdom, centralizing power to himself, power which rarely was used for the benefit of the people. This came out of the ideological vacuum which existed before the French Revolution: without any of the humanizing factors that the concepts of liberalism, socialism, or conservatism created, power politics reigned. The only ideologies that existed as a check to power within Western Europe at this time were Christianity and Feudalism.

Francois had a deep dislike for feudalism, which he saw as an inefficiency, and he didn't seem particularly Christian either: he was unique amongst the Kings of Europe in that his personal Castle was the only Royal castle without a personal chapel. So, without these forces there was nothing left but bare authoritarianism. This isn't to say that the institutional creations of Francois were short lived: the reorganization of the French military created a structure that stayed with France for centuries, with minor tweaks here and there, and the Inquisition would last until the end of the Religious Wars in France. But for all of the new institutions created by Francois, he still created a remarkably brittle state which remained in a precarious situation until emergence of absolutist forms of monarchy in the 16th century. Why?

Because none of the institutions created by Francois benefitted or supported the people. Military reorganizations, increased taxation, the creation of a tax extracting bureaucracy, all of these things supported and were for the government. This led to anger from the undermined classes, which are exemplified in the 2 major crises of the period, one foreign, the other domestic: these were the Bourbon Debt Crisis and the Parisian Tax Riots, respectively.

The Bourbon Debt Crisis

The 100 Years War hit the center of France the hardest--as her resources were diverted to the more important periphery--and gave her the least. The House of Bourbon, situated in their duchy in the very middle of the French Kingdom, gained nothing from the gains of the French government, the new anti-piracy policy, or (given her position in the middle of the country) the new Army Academy. However, she was very much effected by the decreasingly friendly Franco-Burgundian relations, as the Duchy of Burgundy was right at her border.

But through the 100 Years War and the 1450s, the Duke Arnaud Bourbon was a model vassal: going so far as to arrange the French-Burgundian alliance himself, pay for mercenaries to serve as coastal garrisons, but most importantly, he offered to pay, out of pocket, for the French invasion of England. How did the Duke of a small, agricultural province afford such a massive expenditure? By borrowing from his vassals, at generous rates, with the idea that he would gain some of the spoils from England. This assumption came true for a short time: Charles VII agreed to pay off the Duke's first payment at extensive cost to himself, with the suggestion that he may pay the second payment as well. Duke Arnaud returned to his Castle with glee in his heart.

The First Bourbon Debt Crisis, averted

Charles VII died, likely from liver failure, during a feast held in his honor on New Years Day, 1460. This traumatic death led Francois even more towards an austere administration; there were no grand feasts under Francois' reign except in the cases of General Estates Assemblies. But more importantly to the province of Bourbonnais, Francois was far less likely to profligately spend money on his vassals without some other objective: he gave the Orleanais massive wine subsidies, for instance, because Orleans was key to the security of Paris. Bourbonnais was no where near as important as Orleans from a security standpoint, and unlike Provence the Duke de Bourbon was a historical ally and Francois saw no need to bribe him.

When Arnaud came to Paris the second time, asking for money, he was an old man. Barely able to finish a sentence without coughing violently, Arnaud was allowed to make his request without interruption for an hour. At the end of the pathetic display by the Duke, the young and arrogant King Francois asked a simple question before he ended the hearing:

"Why would I pay you, when my own people have so many needs to be met?"

Which set a precedent wherein Francois saw the vassals not as a part of his jurisdiction, but rather as 'variables' to be controlled. For Arnaud, this statement crushed him: he died on the way back to his capital, and his young son Jean-Jacque de Bourbon avowed himself as an enemy of the Crown.

I seriously got this event twice

Those who have read my entries will understand that Francois retained bad relations with his estates throughout his rule. This rivalry was started by the Bourbon debt crisis: because of it, Francois lost someone who could have been his greatest ally.

One of my really crappy maps. This shows the relations between France and her vassals, including the semi-independent Orleans. Shades of blue indicate good relations, shades of red indicate bad relations

The Parisian Tax Riots

As I said in my introduction, much of the policy made in France before the Revolution occurred in an ideological vacuum: in absence of moderating ideological forces, a single-minded lust for power drove the policies of Francois. We can see this most easily through Francois' policies that led to the Parisian Tax Riots. The Parisian Tax riots, contrary to the name, were about more than merely taxes: they were about the King's oppressive measures against the nobility, his misuse of his new Inquisitorial power, and the lack of growth in the French economy while the French government grew rapidly. But the tax riots were also about taxes.

Another poorly made map showing tax increases through the Kingdom. Blue means no tax increases were had, yellow means a tax increase from 10-20%, orange means a 20-40% increase, and red means a 50%+ increase in taxes

As I said before, one of Francois' first acts as King was to ban the chartering of markets and ports without a tax assessor. But he went farther than that: before Francois ascended to the throne there were two tax assessors, in Paris and Toulouse. By 1470 every province north of Blois had a tax assessing firm, connected to the loosely chartered General Bank (or Banque Generale). This lowered on frivolous spending in the provinces but also greatly increased the French crown's money.

The French treasury in 1471, right before her War of Conquest. For contrast, I made less than 30 ducats a month in the 1450s

The problem was that Francois went too far. The fact that merely assessing his provinces taxes increased his funds gave him the impression that his provinces were severely undertaxed. And so he set Manchini in charge of the Banque Generale as well as the Cosmopolitaine Inquisition, and ordered him to set up a tax code for the Northern provinces which would maximize the funds gained by the government. This led to overtaxation, to the degree that revolts within the North were a consistent threat to the Valois royalty. But Francois didn't see these revolts as a problem: rather he saw them as signs of success--the people were temporarily enraged at having to pay taxes, sometimes for the first time. And so, instead of lowering taxes, Francois worked on measures to attack the dissent caused by taxes. He attacked burgher dissent using 'carrots' and benefits, and attacked peasant dissent via 'sticks', or the Inquisition. It ended up being the 'stick' that hurt the King the most

The protection of French Merchants

The French mercantile elite was one of the groups most heavily targeted by the new taxes: unlike the Nobility, they had little power within the court but they had much taxable wealth. Thus, Parisian burghers were a massive group in the newly forming anti-taxation movement in the French north. This is because the taxes came in at a time when the French merchants were suddenly facing renewed competition. Italian and German traders mostly stuck to their, richer, centers of trade, which left the French with a free reign within Paris through the 1460s. Why a 'free' reign? Because the effects of the 100 Years War were still being felt through England. With the South-East impoverished and the South-West disconnected from the government, an alliance of local petty-gentry and Londoner traders rebelled against the incompetent Regency Council in a civil war that lasted a decade.

Now that's what I call good policy!

But in 1468, the Yorkshire Treaty between the self titled Republic of London and the House of Lancaster ousted the hated Regency Council and put, in its place, King George I, a King who, while he was able to crush republican elements within a few short years, still supported the mercantile elite. For the first time in 10 years, English merchants were again to be found in Venice, Seville, Stockholm, and Paris. This weakened the profits of French traders while they were being increasingly taxed. Furthermore, the profits of Paris had, by 1468, started to attract richer noblemen, who formed their own trading guilds and were competing with the French burghers. Francois responded to this with, as I said, a 'carrot'. He ordered a protection of Parisian merchants from competition with foreign and noble traders, and banned aristocrats from mercantile acts. This (temporary) separation of noble and mercantile powers won burgher support for Francois, to the degree that many burghers became the first Tax Assessors.

The Protection of French Merchants Act. The restriction of aristocratic mercantile activities was consistently renewed (with the exception of New France)

The Inquisitorial Crisis

As I said, the Inquisition was used in the South in a similar fashion to the Spanish Inquisition, rooting out the Cathar heresy and attacking the small communities of French Jews which dotted the Occitan countryside. However, in the North they were used in an altogether different context: they were used to enforce tax codes. Inquisitors and Clergymen were hired by the state to sing praise of the glory of paying ones King, and the image of the Tax Collector was often accompanied in the Early Renaissance by an Inquisitor who would threaten hellfire and brimstone if a community didn't pay their levy.

I realize that I didn't show the slider effects of the Inquisition. Here they are!

Through the 1460s, Manchini developed an extensive law of how much any group of people should pay: taxes were to be paid communally, which had the side effect which meant that they were mostly paid by the lower classes. However, there were exceptions to this rule: large estate owners had to pay a certain amount, as did religious minorities. Inquisitorial support meant that those who were found to be tax evaders were tortured until they reaffirmed their love of the French King. This went on for the better part of the decade, giving the French crown money at the loss of international prestige (the Papacy definitely disliked the misuse of the Inquisition). This was until the Excommunication of Aix-En-Othe.

The Excommunication of the Mayor of Aix-En-Othe, and the rest of the town

Aix-en-Othe was a small town to the southwest of Paris. Its mayor, a clever man with friends in the local tax assessing firm, found multiple loopholes which allowed his town to nearly completely avoid their taxes. Each year for 5 years, the Inquisitor and the Tax Collector would come, and he would give a total of 50 florins (In game=.05 ducats), an amount that was roughly a tenth of what the province should have been paying. When Mancini found this out, he made the decision to use the Inquisition to excommunicate the whole town. This nearly destroyed the community. Hundreds left, the mayor committed suicide, and Orleanais noblemen bought most of the town's land.

When this was found out, it cause an uproar throughout France. If the King could simply excommunicate his subjects, who was next? The act led to widespread calls for the sacking and trial of Manchini, as well as a tax riot in Paris led by local noblemen and peasants and numbering 20,000 strong. Although Francois kept Mancini as his interior minister, the incident led him to undo his taxation policies, and it greatly effected his personality.

The Aix-en-Othe crisis

Been considering trying MMP, looks good so far, keep it up!

yeah, MMP is great. Even with the fact that DW used a lot of Magna Mundi's innovations, it still has a lot of other things (like Estates meetings) that make it the AAR writer/social scientist's dream.

I have a question for everyone who plays MM: how do you take a colonization route without getting the awful Naval Provisionings idea? I really can't take any NI's that don't move me towards one of my advanced National Ideas (for those who don't know, Liberte Egalite Fraternite, Naval Glory, QFTNW, Scientific Revolution and Glorious Arms all require 4 ideas of their type in MM. Some ideas, like Cabinet, count towards multiple advanced NIs, ergo I took it first), and if I need a naval idea (I do) I'm taking Advanced Shipwrights because that moves me towards scientific revolution. But having a New France is also rather important to me and this AAR: in Lords of Prussia I wasn't playing a Colonizing power, and having a colony will give me something extra to write about (as if I don't have enough)

First and foremost, Rest in Peace Magna Mundi the Game. I guess I'll never write that MMtG historybook AAR. In its place I dedicate this AAR to the game that could have been.

Now, without further a due, we return to your irregularly scheduled AAR.

The War of The Vendee League

The Situation and the Order of Battle

The 1470s began on a dark note for the Francois I government. Although she was (militarily) stronger than ever before, the Parisian Tax Riots both demolished France's international repute ('Troubles in X', which forces you to choose between either 5-10K rebels or a 10 prestige malus, triggers a lot when you have provinces with 'high' or 'very high' taxes, occurred several times in the 1460s.) and took the better part of a year to put down. The continuing diplomatic campaign against Burgundian legitimacy seemed to be getting worse every day, as the Duchy announced that they had inherited the Duchy of Milan.

oh no!

But the worst news of the year came in the winter of 1472: the English had declared war upon the Bretons.

English soldiers besieging Morbihan.

The Breton-English war was nominally over a claim to the County of Finistere. In reality, it was made as a domestic move (to retake England's place in the international scene and show the strength of English arms), as a way to drag Brittany's ally Scotland into another War, and as a way to undo the embarrassment of Treaty of London by reestablishing a base on the Continent.

This move violently startled the French government: if the English were to take Finistere--or worse, vassalize Brittany--then all of the gains made in the 1450s and 60s would be for naught. However, the war brought an opportunity: the Duchy of Burgundy and the Kingdom of Aragon (both previous Breton allies) had reneged on their alliance following the English declaration of War. This meant that the French could destroy one of the possible 'variables' in an imagined Franco-Burgundian War: the threat of a flanking by the Duchy of Brittany. Furthermore, the Duchy of Brittany had constructed what would have been an impressive anti-French League of Vendee, involving Burgundy, Savoy, Lorraine, and Aragon. Without Burgundy and Aragon though, a war against Brittany meant that France could possibly defeat 3 foes who, though unimportant in and of themselves, could possibly turn on France in critical moments.

But right now, because of wars afflicting Brittany and Savoy, the combined force of the League amounted to less than 20,000 men, separated my hundreds of miles. France had the advantage of interior lines, as well as the advantage of an army far larger than her opponents. She had every advantage besides one: she was going on the offensive, which put de Villenueve on edge. The cabinet meeting discussing possibilities of offensives into Savoy, Lorraine and Brittany thus led to a break in what had been a cross-generational alliance between de Villenueve and the King.

French Generals in 1472, and the Generals becoming an independent corporate force following their separation from the King.

The King argued that, although the Kingdom's objectives were far reaching (total conquest of Lorraine, Savoy, and Brittany), France's numeral advantage, technological advantage, and doctrinal advantage meant that victory would be assured. De Villenueve countered by saying that the doctrinal advantage given by On Command wouldn't apply he applied here: On Command very strongly suggested defensives over offensives. And victory wasn't what De Villenueve was worried about: what he was worried about was that thousands upon thousands of French soldiers would die, regardless of how good that tactics of the campaigns would be. It soon became clear to de Villenueve and the French Marshals that even though Francois I spoke about the strategies present in On Command, he didn't truly understand them and his misunderstanding would lead to a huge mass of deaths. At the same time, however, controlling the French hinterland was immensely important because it would allow France to keep most of her armies posed against her true enemy, the Duchy of Burgundy.

However, the belligerent and aggressive style of Francois' war plans prompted a move towards independence by the Marshals. De Villenueve, acting as head of the army, designated Francois I as the Commander in Chief of the Lorainian Front, leaving the Breton front for himself and the first valedictorian of the French Army Academy, the Comte Crevecouer. Hailing from the north of France, de Crevecouer chose to leave his life of luxury as the heir to a massive estate after reading On Command, and instead moved to Othe to study in the Academy, focusing on tactical applications to de Villenueve's strategic vision. The Savoyard front was given to the Auvergnian Marshal, Charles de Rochemaure, for reasons I will get into in the next section. The French order of battle was as follows:

The position of French armies at the beginning of the War of the Vendee League. Note that a new general would be promoted to lead the Armee de l'Est, which besieged Vendee, and 5,000 men were trained to supplement the Royal Army.

The Strategy

The objectives were, first, to engage and destroy the enemy armies, and secondly to subjugate the whole of each enemy's territory. In Brittany, a series of military governorships and local governments would be set up to prepare the Breton provinces for incorporation into the French country. In Savoy and Lorraine, problematic province governors would be replaced with more cooperative locals, but the goal for these duchies was vassalization and incorporation into the French kingdom, so more brutal strategies were ruled out. In Savoy in particular, Auvergnan and Provencal noble generals were told that any counties well governed by the French army would pass to them.

The Savoyard Theatre

The first army to engage was the Savoyard army. Knowing that the Army of Flandres was coming to them, they hoped to minimize political losses by having the battle occur as close to the French border as possible. Furthermore Duke Antonio of Savoy knew that supply wouldn't be a problem for France: unlike the Breton or Lorainian theatres, the French would be able to supply by sea via their naval dominance, and Antonio knew that the Francophone villages would side with the French, almost completely negating the necessity for supply lines.

However, de Rochemaure's (not Rochemause as the picture says) cavalry saw the Savoyard army advancing and were able to inform the French well ahead of time, and so the Army of Flandres maneuvered around the lumbering Army of Savoy and continued towards Turin, forcing the enemy back without a casualty. This continued for several days, with the French army outmaneuvering the Savoyard army again and again, while keeping her supply lines and attacking her enemies. The Battle of Turin ended up happening 2 weeks after the initial invasion into Piedmont, with a well rested French army fighting against an exhausted Savoyard force. The Army of Savoy collapsed, and the rest of the Savoyard campaign consisted of besieging of the remnants of the Savoyard army and buying over the Savoyard populace.

The Savoyard Campaign was effectively over within a month

The Lorainian Theatre

The Loranian Campaign took a little bit longer: though Lorraine's army was just as poorly trained, her army was larger and had positioned itself farther into the Loranian countryside, with spies and scouts ready to inform their army of the Royal Army's position. Unlike de Rochemaure, Francois attacked his enemy head on, leading to the Battle of Harville several miles west of the city of Metz, by the Riene Forrest. Although Lorraine had started to implement pikes into her infantry, the full consequences of pike tactics had been lost on the Lorainian generals, leading them to ask why the Royal Army had deployed without her 3,000 cavalrymen, and, foolishly thinking that the French army had lost several regiments in the march, ordered an en masse charge that led to the deaths of hundreds of Loranian infantry and many cavalry.

The Battle of Harville

Francois' cavalry, then refreshed and unbattered by the battle, harried the Lorainian soldiers all the way back to Lothloringen, the capital. There, starved and beaten, the Army of Loraine surrendered to the cavalry captain Louis de la Motte d'Airan, whom I will call the Comte d'Airan. This decisive victory showed to all of Europe the superiority of French arms, and went a long way in undoing the damage dealt to French prestige by the excesses of the Cosmopolitaine Inquisition. Lastly, the victory at Lothloringen led to the promotion of the Comte d'Airan to the rank of General, and he was swiftly put in command of the Armee de l'Est, both as a way to fix the deficit of leadership there (although the Army de L'Est was acting admirably without a major general at the helm and was the first army to finish a siege during the war) and as a way to put a general who followed Francois' strategic vision into the ranks of the Marshals.

The Surrender at Lothloringen

The Breton Theatre

Brittany was an all together different situation than the other 2 theatres I've mentioned. Loraine was a small duchy, and French attacks in to it could use the Provencal county of Barrois as a base of operations. Savoy was similarly laid out to the French countryside and contained many communities who pledged their allegiance to France. Brittany, on the other hand, was an all together different matter. For decades, the Dukes of Brittany had been centralizing their rule and uniting their people against the specter of the French Kingdom meant that the Armees de l'Est et de Nord would be fighting on hostile ground, and the Paimpont Forest of Arthurian legend provided a perfect place for the Breton army to withdraw to in the possibility of defeat (Or something: the Breton army disappeared for like a year and then reappeared. No clue how this happened.). Moreover, the Army of Brittany had been following advances made in France, and On Command was widely read among the officer corps, and his lessons were deftly applied against the French army. Rather than face the far larger French and English armies head on, the Armee de Breton dispersed into the wilderness, attacking French supply lines, her hospitals, her camps.

This all angered de Villenueve to no end. After telling his King not to engage in an offensive campaign, after writing a book on the advantages on defensives, he was being faced with an enemy who knew, precisely, how to implement his strategies against him, and he had no clue how to beat them. During the winter of 1472, de Villenueve kept the Marshals up, night after night, reading military histories for a way to defeat an enemy as deeply entrenched as the Duke of Brittany. It ended up being Mancini, the widely hated and sadistic head of the French 1st Department (Covering Culture, Taxes, and the Inquisition), who had a solution, related to his own past in the Inquisition: the lands of Brittany would be forcefully Francofied via a colonization by French elites. Breton nobles would be demoted, relocated, or killed.

Unsurprisingly, the tactics used by both sides of the war in Brittany led to much bloodshed. The Breton front ended up taking the lives of 15,000 French soldiers, more than half of the total casualties. The effects on the Breton countryside were similarly disastrous: whole towns and estates were swallowed up, in fire and blood, and when confronted with the massive Painpont Forest, a massive deforestation campaign was implemented.

With all this said, the campaign to destroy the enemy army went well at first. The sneak attack that Francois I had arranged for was successful: the Armee de l'Est caught the army guarding Vendee by surprise, and was able to destroy them in a single blow.

The campaign of Vendee ended in a single battle, the rest of the troops scattered into the Painpont Forest

The campaign to destroy the Armee de Breton was far more difficult. Duke Jean II harried the Armee de Nord for weeks, until he was finally forced to fight with his back to the hills. Unlike his foolish allies, Jean II did not march directly into French pikes, instead he entrenched himself in a position and used his longbowmen to do as much damage as they could. What he did not anticipate was that the French light cavalry would march through the hills and attack his rear, which sent his army into a well organized withdrawal but cost the Breton Duke his life.

Jean II was but the first Duke to die to foreign steel during the 1470s

Jean's nephew, Pierre II was barely older than 17 when he was given the Crown in Morbihan at the news of his uncle's death. With a fire in his heart, he ordered an advance to attack the French army in the passes of the Painpont Forest. The battle was a disaster: the Armee de Nord, though spread over several roads, was able to keep its composure and place its pikes towards the enemy, and the Breton soldiers died in their thousands. For a short time, the battle of Painpont meant that the Breton army was inoperable.

The Battle of Painpont Forest

The War's End

This is good, because as time dragged on, the most deadly force for the French reared its ugly head: disease, starvation, and attacks by militas led to the deaths of thousands of Frenchmen in the Duchy of Brittany. For the next two years, the soldiers of France besieged fortresses, bought off local lords, fought against Breton partisans, and so forth. By 1475, critical enemy fortresses in Lorraine, Savoy, and Brittany were taken and the process of treaty making started. D'Ursine, who'd stayed by his King's side for the better part of the Lorainian campaign, had by 1475 convinced his King to vassalize Loraine and Savoy and add them to the ranks of the General Assembly. By doing so, he'd entrenched the General Assembly's power for multiple generations. However, by his diplomatic abilities he was also able to extract major concessions from the Vendee league, which essentially paid the cost for the war.

The Peace treaties with the Savoyard and Lorainian belligerents

Brittany was destined for a different fate: she was forced to give up most of her provinces, who were steadily colonized through the rest of the 1470s and 80s. In a single stroke, Francois I had eliminated every threat to him in the war and succeeded beyond his wildest dreams.

The First treaty of Vendee

I've been wondering about this AAR: although this section is mostly going over things present in EU3, should I have 'Beginners Corners' like Narwal AARs, to explain Magna Mundi mechanics? Would that make the AAR more accessible to non-MM players?

Now, without further a due, we return to your irregularly scheduled AAR.

The War of The Vendee League

The Situation and the Order of Battle

The 1470s began on a dark note for the Francois I government. Although she was (militarily) stronger than ever before, the Parisian Tax Riots both demolished France's international repute ('Troubles in X', which forces you to choose between either 5-10K rebels or a 10 prestige malus, triggers a lot when you have provinces with 'high' or 'very high' taxes, occurred several times in the 1460s.) and took the better part of a year to put down. The continuing diplomatic campaign against Burgundian legitimacy seemed to be getting worse every day, as the Duchy announced that they had inherited the Duchy of Milan.

oh no!

But the worst news of the year came in the winter of 1472: the English had declared war upon the Bretons.

English soldiers besieging Morbihan.

The Breton-English war was nominally over a claim to the County of Finistere. In reality, it was made as a domestic move (to retake England's place in the international scene and show the strength of English arms), as a way to drag Brittany's ally Scotland into another War, and as a way to undo the embarrassment of Treaty of London by reestablishing a base on the Continent.

This move violently startled the French government: if the English were to take Finistere--or worse, vassalize Brittany--then all of the gains made in the 1450s and 60s would be for naught. However, the war brought an opportunity: the Duchy of Burgundy and the Kingdom of Aragon (both previous Breton allies) had reneged on their alliance following the English declaration of War. This meant that the French could destroy one of the possible 'variables' in an imagined Franco-Burgundian War: the threat of a flanking by the Duchy of Brittany. Furthermore, the Duchy of Brittany had constructed what would have been an impressive anti-French League of Vendee, involving Burgundy, Savoy, Lorraine, and Aragon. Without Burgundy and Aragon though, a war against Brittany meant that France could possibly defeat 3 foes who, though unimportant in and of themselves, could possibly turn on France in critical moments.

But right now, because of wars afflicting Brittany and Savoy, the combined force of the League amounted to less than 20,000 men, separated my hundreds of miles. France had the advantage of interior lines, as well as the advantage of an army far larger than her opponents. She had every advantage besides one: she was going on the offensive, which put de Villenueve on edge. The cabinet meeting discussing possibilities of offensives into Savoy, Lorraine and Brittany thus led to a break in what had been a cross-generational alliance between de Villenueve and the King.

French Generals in 1472, and the Generals becoming an independent corporate force following their separation from the King.

The King argued that, although the Kingdom's objectives were far reaching (total conquest of Lorraine, Savoy, and Brittany), France's numeral advantage, technological advantage, and doctrinal advantage meant that victory would be assured. De Villenueve countered by saying that the doctrinal advantage given by On Command wouldn't apply he applied here: On Command very strongly suggested defensives over offensives. And victory wasn't what De Villenueve was worried about: what he was worried about was that thousands upon thousands of French soldiers would die, regardless of how good that tactics of the campaigns would be. It soon became clear to de Villenueve and the French Marshals that even though Francois I spoke about the strategies present in On Command, he didn't truly understand them and his misunderstanding would lead to a huge mass of deaths. At the same time, however, controlling the French hinterland was immensely important because it would allow France to keep most of her armies posed against her true enemy, the Duchy of Burgundy.

However, the belligerent and aggressive style of Francois' war plans prompted a move towards independence by the Marshals. De Villenueve, acting as head of the army, designated Francois I as the Commander in Chief of the Lorainian Front, leaving the Breton front for himself and the first valedictorian of the French Army Academy, the Comte Crevecouer. Hailing from the north of France, de Crevecouer chose to leave his life of luxury as the heir to a massive estate after reading On Command, and instead moved to Othe to study in the Academy, focusing on tactical applications to de Villenueve's strategic vision. The Savoyard front was given to the Auvergnian Marshal, Charles de Rochemaure, for reasons I will get into in the next section. The French order of battle was as follows:

The position of French armies at the beginning of the War of the Vendee League. Note that a new general would be promoted to lead the Armee de l'Est, which besieged Vendee, and 5,000 men were trained to supplement the Royal Army.

The Strategy

The objectives were, first, to engage and destroy the enemy armies, and secondly to subjugate the whole of each enemy's territory. In Brittany, a series of military governorships and local governments would be set up to prepare the Breton provinces for incorporation into the French country. In Savoy and Lorraine, problematic province governors would be replaced with more cooperative locals, but the goal for these duchies was vassalization and incorporation into the French kingdom, so more brutal strategies were ruled out. In Savoy in particular, Auvergnan and Provencal noble generals were told that any counties well governed by the French army would pass to them.

The Savoyard Theatre

The first army to engage was the Savoyard army. Knowing that the Army of Flandres was coming to them, they hoped to minimize political losses by having the battle occur as close to the French border as possible. Furthermore Duke Antonio of Savoy knew that supply wouldn't be a problem for France: unlike the Breton or Lorainian theatres, the French would be able to supply by sea via their naval dominance, and Antonio knew that the Francophone villages would side with the French, almost completely negating the necessity for supply lines.

However, de Rochemaure's (not Rochemause as the picture says) cavalry saw the Savoyard army advancing and were able to inform the French well ahead of time, and so the Army of Flandres maneuvered around the lumbering Army of Savoy and continued towards Turin, forcing the enemy back without a casualty. This continued for several days, with the French army outmaneuvering the Savoyard army again and again, while keeping her supply lines and attacking her enemies. The Battle of Turin ended up happening 2 weeks after the initial invasion into Piedmont, with a well rested French army fighting against an exhausted Savoyard force. The Army of Savoy collapsed, and the rest of the Savoyard campaign consisted of besieging of the remnants of the Savoyard army and buying over the Savoyard populace.

The Savoyard Campaign was effectively over within a month

The Lorainian Theatre

The Loranian Campaign took a little bit longer: though Lorraine's army was just as poorly trained, her army was larger and had positioned itself farther into the Loranian countryside, with spies and scouts ready to inform their army of the Royal Army's position. Unlike de Rochemaure, Francois attacked his enemy head on, leading to the Battle of Harville several miles west of the city of Metz, by the Riene Forrest. Although Lorraine had started to implement pikes into her infantry, the full consequences of pike tactics had been lost on the Lorainian generals, leading them to ask why the Royal Army had deployed without her 3,000 cavalrymen, and, foolishly thinking that the French army had lost several regiments in the march, ordered an en masse charge that led to the deaths of hundreds of Loranian infantry and many cavalry.

The Battle of Harville

Francois' cavalry, then refreshed and unbattered by the battle, harried the Lorainian soldiers all the way back to Lothloringen, the capital. There, starved and beaten, the Army of Loraine surrendered to the cavalry captain Louis de la Motte d'Airan, whom I will call the Comte d'Airan. This decisive victory showed to all of Europe the superiority of French arms, and went a long way in undoing the damage dealt to French prestige by the excesses of the Cosmopolitaine Inquisition. Lastly, the victory at Lothloringen led to the promotion of the Comte d'Airan to the rank of General, and he was swiftly put in command of the Armee de l'Est, both as a way to fix the deficit of leadership there (although the Army de L'Est was acting admirably without a major general at the helm and was the first army to finish a siege during the war) and as a way to put a general who followed Francois' strategic vision into the ranks of the Marshals.

The Surrender at Lothloringen

The Breton Theatre

Brittany was an all together different situation than the other 2 theatres I've mentioned. Loraine was a small duchy, and French attacks in to it could use the Provencal county of Barrois as a base of operations. Savoy was similarly laid out to the French countryside and contained many communities who pledged their allegiance to France. Brittany, on the other hand, was an all together different matter. For decades, the Dukes of Brittany had been centralizing their rule and uniting their people against the specter of the French Kingdom meant that the Armees de l'Est et de Nord would be fighting on hostile ground, and the Paimpont Forest of Arthurian legend provided a perfect place for the Breton army to withdraw to in the possibility of defeat (Or something: the Breton army disappeared for like a year and then reappeared. No clue how this happened.). Moreover, the Army of Brittany had been following advances made in France, and On Command was widely read among the officer corps, and his lessons were deftly applied against the French army. Rather than face the far larger French and English armies head on, the Armee de Breton dispersed into the wilderness, attacking French supply lines, her hospitals, her camps.

This all angered de Villenueve to no end. After telling his King not to engage in an offensive campaign, after writing a book on the advantages on defensives, he was being faced with an enemy who knew, precisely, how to implement his strategies against him, and he had no clue how to beat them. During the winter of 1472, de Villenueve kept the Marshals up, night after night, reading military histories for a way to defeat an enemy as deeply entrenched as the Duke of Brittany. It ended up being Mancini, the widely hated and sadistic head of the French 1st Department (Covering Culture, Taxes, and the Inquisition), who had a solution, related to his own past in the Inquisition: the lands of Brittany would be forcefully Francofied via a colonization by French elites. Breton nobles would be demoted, relocated, or killed.

Unsurprisingly, the tactics used by both sides of the war in Brittany led to much bloodshed. The Breton front ended up taking the lives of 15,000 French soldiers, more than half of the total casualties. The effects on the Breton countryside were similarly disastrous: whole towns and estates were swallowed up, in fire and blood, and when confronted with the massive Painpont Forest, a massive deforestation campaign was implemented.

With all this said, the campaign to destroy the enemy army went well at first. The sneak attack that Francois I had arranged for was successful: the Armee de l'Est caught the army guarding Vendee by surprise, and was able to destroy them in a single blow.

The campaign of Vendee ended in a single battle, the rest of the troops scattered into the Painpont Forest

The campaign to destroy the Armee de Breton was far more difficult. Duke Jean II harried the Armee de Nord for weeks, until he was finally forced to fight with his back to the hills. Unlike his foolish allies, Jean II did not march directly into French pikes, instead he entrenched himself in a position and used his longbowmen to do as much damage as they could. What he did not anticipate was that the French light cavalry would march through the hills and attack his rear, which sent his army into a well organized withdrawal but cost the Breton Duke his life.

Jean II was but the first Duke to die to foreign steel during the 1470s

Jean's nephew, Pierre II was barely older than 17 when he was given the Crown in Morbihan at the news of his uncle's death. With a fire in his heart, he ordered an advance to attack the French army in the passes of the Painpont Forest. The battle was a disaster: the Armee de Nord, though spread over several roads, was able to keep its composure and place its pikes towards the enemy, and the Breton soldiers died in their thousands. For a short time, the battle of Painpont meant that the Breton army was inoperable.

The Battle of Painpont Forest

The War's End

This is good, because as time dragged on, the most deadly force for the French reared its ugly head: disease, starvation, and attacks by militas led to the deaths of thousands of Frenchmen in the Duchy of Brittany. For the next two years, the soldiers of France besieged fortresses, bought off local lords, fought against Breton partisans, and so forth. By 1475, critical enemy fortresses in Lorraine, Savoy, and Brittany were taken and the process of treaty making started. D'Ursine, who'd stayed by his King's side for the better part of the Lorainian campaign, had by 1475 convinced his King to vassalize Loraine and Savoy and add them to the ranks of the General Assembly. By doing so, he'd entrenched the General Assembly's power for multiple generations. However, by his diplomatic abilities he was also able to extract major concessions from the Vendee league, which essentially paid the cost for the war.

The Peace treaties with the Savoyard and Lorainian belligerents

Brittany was destined for a different fate: she was forced to give up most of her provinces, who were steadily colonized through the rest of the 1470s and 80s. In a single stroke, Francois I had eliminated every threat to him in the war and succeeded beyond his wildest dreams.

The First treaty of Vendee

I've been wondering about this AAR: although this section is mostly going over things present in EU3, should I have 'Beginners Corners' like Narwal AARs, to explain Magna Mundi mechanics? Would that make the AAR more accessible to non-MM players?

Last edited:

I've been wondering about this AAR: although this section is mostly going over things present in EU3, should I have 'Beginners Corners' like Narwal AARs, to explain Magna Mundi mechanics? Would that make the AAR more accessible to non-MM players?

Another great AAR! It would be fantastic if you could, I've tried getting into MMU a couple of times but it is somewhat overwhelming.

I very interesting and detailed history book AAR here which I'm really enjoying.

I never read your Lords of Prussia AAR, but might give it a read after this.

I never read your Lords of Prussia AAR, but might give it a read after this.

Another great AAR! It would be fantastic if you could, I've tried getting into MMU a couple of times but it is somewhat overwhelming.

Great! My first one is probably going to be on the vassals system, to explain the general estates meetings. I'm a big fan of the way that vassals are implemented in EU3, and I haven't really experienced as prolonged a House of High Lords (what you get when you have 3+ vassals)...it's a huge counter to French early predominance, and once I explain it, you'll see that I actually made a really silly choice in vassalizing Lorraine and Savoy, because it put me into a worse vassal problem than I had before.

I very interesting and detailed history book AAR here which I'm really enjoying.

I never read your Lords of Prussia AAR, but might give it a read after this.

Thank you, for the comment and the reading Lords of Prussia possibly thing!