Colbert’s Early Administration, 1653-1670

From Lords of France, by A. de Tocqueville

Jean-Baptiste Colbert was the greatest economic actor in 17th century France besides Henri II. Born the son of common merchants, his family’s fortunes rose when his father entered the services of the Tocqueville’s Postage Company, and from there moved to the Ministry of the Treasury. Jean-Baptiste followed his father’s footsteps in the 1640s, joining the Treasury and later the Ministry of Trade in the early 1650s. Over the course of the Fronde he remained in rebel-occupied Paris, and at the end of the Fronde he negotiated on the side of the Parisian parlement and proved instrumental in the creation of the municipal provinces, although his original documents show a far more wide ranging set of reforms which rested on the idea of a degree of autonomy for the cities, reforms which did not reach the king but remained in Colbert’s head. For this, he was given an estate in Burgundy, the title of Marquis, and the undersecretariat of the newly formed Ministry of Taxes & Trade.

From this position, Colbert was able to deal with the new kind of French economy he had created in his Parisian negotiations. Focusing on several key cities, Colbert worked from the 1650s to the 1680s, sometimes alone, sometimes with the cooperation of other ministers (particularly Vauban), sometimes in conflict with other ministers (particularly Louvois the Elder), in order to increase the production of France in order to compete with her Medici and Habsburg rivals. In some cases this involved the continuation of Henrian policies, such as the Rhone Canal project, but in many cases it involved the repudiation of the Henrian spirit alongside a focus on Henrian letters.

Jean Baptiste Colbert, Minister of the French Kingdom from 1656-1695

It is ironic, then, that Jean-Baptiste would not have succeeded if it weren’t for Henri II. His father’s position in the treasury only came to him via the passing over of several aristocratic candidates, an event which would not have happened under previous monarchs. Furthermore, the Ecole d’Administration was created only a year before Jean Baptiste came of age, and he was able to rise so swiftly because the narrative of the ‘new man’, the intellectual bureaucrat who had such a strong imaginary presence in Henri’s regime, had already set up the rise of man such as Jean Baptiste.

On the council, Colbert faced the stubborn resistance of the Comte de Louvois, who viewed him as a bourgeois upstart and who opposed Colbert’s economic schemes, preferring more money be spent in the army. Furthermore he faced the resistance of the Duc d’Anjou, the secretary of Taxes & Trade and a friend of Louvois. This meant that Colbert rarely got anything, from taxes to spending, through the council, and after an outburst when he accused Louvois of Frondeurship, d’Anjou asked him not to attend the council meetings and instead assigned him to the Rhone Canal project. During this project Colbert met the already illustrious Vauban, and the two young (relatively, they were in their thirties which made them very young for the Council) reformers soon grew to appreciate each other’s skills. The lack of resources for the two men had for their respective projects (Vauban’s building of a star fort in Bresse and Colbert’s canal project) led to a form of barter between the two, wherein Colbert would petition local cities for funds to the star fortress and get a brigade of engineers for his canal.

The canal project did more than garner connections between him and Vauban, he was also able to see up close the way that the provinces were ruled, the relationship between the provincial rulers and the intendants, and he was able to experience the sheer number of ways one could make money if one were to give up some of their scruples. One of the ways that Colbert was able to fund the canal project on such a tight budget was the creation of an informal set of tolls which would allow traders to ship their wares along government ships. Through this and the use of Vauban’s engineers, Colbert was able to build the Rhone canal far ahead of schedule, and just in time for the beginning of the War of the Rhine.

The modern Rhone Canal, Vauban was only able to complete the southern portion, which connected Lyons to Montpelier. This was still a monumental achievement, on par with Henri’s connection of the Seine to the Scheldt

The War of the Rhine led to both the Duc D’Anjou and Louvois the elder leaving the Council (along with Louis XIII) to lead the French Army. The removal of Colbert’s rivals just as he was called back to the capital allowed Colbert to finally show his mettle to the King, though most of his efforts became embroiled in reinforcing the French army, but as he did that he was able to implement several of Louis’ proposed changes of the army. The creation of a set of regulators (lieutenant colonels) who made sure that each brigade and company were actually the size reported to the government cut down massively on fraud by colonels who artificially expanded their company rosters in order to line their pockets with the crown’s money.

This was hardly enough, though. The cost of both rapidly increasing the army, of transporting nearly 30,000 reinforcements to the frontlines, and of feeding the French army during a bad harvest (in all areas outside of the South, which was now going moving into the beginning of the Olive Oil Bust), swiftly ate into what savings the French state had and by the spring of 1666, the French state was already several hundred thousand livres in debt. By the end of the war, the debt would balloon to four million livres, but this was not the largest event for Colbert.

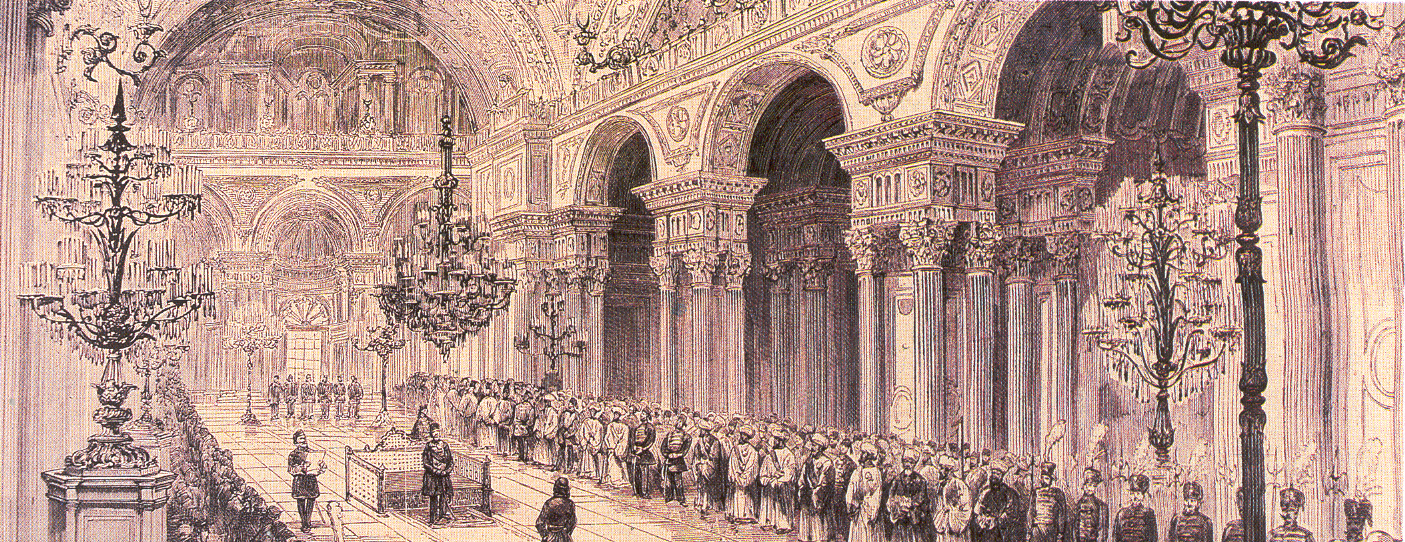

No, the most important event was the death of both Colbert’s rival and his superior, Louvois and d’Anjou, on the field of battle. These deaths both made Colbert the acting head of the Council, and with Louis’ permission, the right to fill the missing seats on the council with anyone he wished.

Colbert filled the council with men close to him, from Ponticherry for the Navy and the Colonies, to Rouissins for Forestry & Mines, to Vauban for the army. But his first issue was the imminent bankruptcy of France, which he managed to avoid in a flurry of activity which became his only mode of being. Bonds were released at 12% interest, which funded a large portion of the immediate French debt and were paid off within the next year by a new run of bonds at 10% (filled with another group of bonds at 8% and so on). Titles were sold, amneties and tax relief sold, and outside the municipal districts even mayorships were auctioned off. When Colbert reached the last outstanding debt, he paid it off via an old trick used by Finance Ministers through France’s history; he devalued the currency while taking out new loans and then immediately revalued it in order to pay those loans off. Colbert rose inflation to a massive degree in the last four years of the 1660s, but while the Livre was worth a half of what it was in 1650, he still managed to get through the decade without bankruptcy.

The Louis was the highest valued coin in the French currency in the 17th century. However its valuation was based entirely by decree, which allowed ministers to devalue and revalue the coins without actually minting new coins (which cost gold). Colbert’s trick involved lowering the Louis’ value to 80 sous while taking out new loans, and then paying those loans back with the new 100 sous Louis’ that he changed. This was a real tactic used by many Enlightenment and Renaissance ministers

The next crisis involved the creation of the province of Perche and the governorships system, and ended with Colbert’s total subsumption of his longer term goals into the service of the state. Colbert had stepped into the Parisian parliament with an idea; that the French government would be simplified, and that its medieval institutions would be eliminated in order to create a more efficient and liberated government. What Colbert ended up seeing, in the south of France and later in his life, was that things were not so easy. The provincial rulers, being picked from the local nobility, were deeply connected to other power structures, and to empower those below them or create power structures above them would provoke rebellion.

And so Colbert, who sought an efficient and simple government above all else, participated in the creation of a new structure of provincial government, the military governorships, who became the acting lords of France in the time of Louis XIII. France, in fact, became even more byzantine, with provincial lords being steadily weakened, both in the council, where their ministries were made smaller and replaced with other ministries which were either more broad [such as Colbert’s ministry which overlapped with the Treasury and the Trade Ministry], or more narrow [the army was actually given four separate ministries for the four branches of the French army--the infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineer groups], and in their provinces, where many of their roles were replaced by Governors (who gained the ability to pay for projects via tolls), who while more powerful and rich than their lordly counterparts represented a lower level of government. Beyond this, the intendants were given slightly more power while not having any connection to localities or provinces.

In time, this would lead to Henri III’s ability to remain a detached though absolute monarch via his manipulation of provincial and governmental authorities. But Colbert had fully realized that this was a temporary fix, that the creation of a new elite would not fix the problems of the old, and that a retrenchment would soon come to the fore.

But in the meantime, he had more authority to do as he wished.

Provincial rule from Henri II to Louis XIII

Sorry for lack of response to comments, my internet's been shoddy the last two days.

.jpg)