Report to the Treasury on the causes of French non-industrialization

Written by Henri de Saint-Simon, Undersecretary of the Bureau of Machines and the Arts. Presented to the National Treasury on the 6th of June, 1787, Year VIII

I. Introduction

The prolonged economic crisis of the Revolution has spurned some to ask: why has France remained such an economic laggard? Why is the most culturally, intellectually, and military advanced country in the world incapable of supporting a steel industry large enough to arm her armies, incapable of paying her debts even though she borrows at ludicrously low rates from her sister republics, incapable of competing with the insignificant island-nation to her north?

In short, why has France no industry for herself, why is commerce still such a weak element of the French economy, why does France not possess the modern economy which Britain has crafted for itself over the last thirty years?

This is a difficult question, but I will do my best to explain the industrial situation in France, going back to the origins of French commerce during the reign of Louis XIII. This section will be both a broader discussion of the nature and limitations of the French economy, as well as a discussion of elements specific to Louis XIII’s reign. It will be the first in a five section report on the state of the French economy, historically, and what can be done to solve it’s problems.

First, I will argue that the nature of French ‘non-industrialization’ is overstated, and argue that we often compare ourselves to an idealized view of both contemporary and historical England. Secondly, I will give a tripartite discussion of the limitations in the French economy, limitations which were exacerbated by Louis XIII but preceded him.

II. French Industrialization

The first issue one must tackle when one asks ‘why has France not industrialized’ is what exactly the question means. The presumption that France remains the wholly agrarian feudal society of the 14th century is certainly not true now, nor was it true a century ago. France is a highly diverse economy, and to characterize the whole of it is to make an egregious mistake. Those who say that France has not industrialized are surely not speaking of France’s artisanal workshops, or her luxury goods industries which remain the most advanced in the world. No they speak to a specific form of industrialization, the industrialization which we imagine has occurred in Britain.

What does this mean? What do we imagine in Britain when we say that it has industrialized? When we speak of industrialization we speak of the British textile industry, the British steel industry, we imagine vast factories which employ hundreds of workers, all working in specialized tasks, all powered with coal. In short, the proponents of the English model assume that Adam Smith described the British economy as it was in 1775, rather than describing the kind of economy he thought it should move towards.

The whole world looks at Manchester and sees an unparallel level of industrialization. While this is true, it is a mistake to presume that all of Britain is like Manchester

So let us say that, firstly, the English economy is no where near as advanced as we have led ourselves to believe, and secondly, that France’s economy is not as much of a laggard as we fear. We imagine Britain to be populated by massive factories, but our spies have found only five textile and steel firms which employ more than five hundred workers, located in Manchester and southern Wales. Yes, France retains the same rural industry that she has had for centuries but that has led to a highly diversified labor market. In the countryside, households are not merely agrarian actors but also work in arms manufactories, finish textiles, and create a large number of other minor but necessary goods such as leather, spades, and furniture.

Furthermore, in the cities France has a highly educated and skilled set of artisans who have provided the world with some of the best craft items. Our fine glassworks, silk industry, and construction industries all benefit from an unmatched level of craftsmanship. Lastly France’s industrial technology is not lagging as much as we fear in Paris. The last five years have seen the opening of chemical plants, soda factories, and machine works throughout France, all of which are mostly new inventions. Furthermore, in specific areas such as Normandy we have seen the beginnings of widespread use of industrial machines such as carding machines and looms. Lastly, French labor is as much as 47% cheaper in France as in England, and the French worker, bolstered by their well trained brethren, produce fine goods.

This is not to say, however, that France does not have considerable setbacks. And many elements of the French economy which have been her strength since the rule of Louis XIII are now chokepoints in French industrialization.

III. Elements of Backwardness in the French Economy

Ironically, many of the elements furnished by Louis XIII, which helped France become the strongest economy in the world in the early 18th century, are elements which now hold us back as we enter the 19th. These include many elements which I will attempt to disaggregate, but they include the dependence of the French economy on artisanal and luxury goods which is related to the lagging consumption levels of the French worker, the system of tolls, and lastly, the system of guilds and corporations which both survive due to and promote the first two systems.

A) Artisanal and Luxury Items

Over the last century the main product of the French economy has been high quality luxury goods. From silk tapestries and mahogany furniture to hunting pistols and watches, the luxury market has formed 24% of all purchases and 73% of all manufactures in France since the sales tax was instituted, which can be presumed to be only slightly inflated in an economy recovering from a recession. While this has been seen as a positive, it both indicates a larger problem and makes the resolution of that problem more difficult. The problem is that the French artisan economy is wholly oriented around the consumption of an elite few who can afford items like silk or mahogany rather than the people. This has its origins in the early development of our country since Colbert’s economic regime.

Colbert, looking to revive the French city, gave duty free accessibility to colonial goods to each of the French municipalities so long as they went to the artisanal industries of France. Soon, naturalized silk was used all along Flanders and in the Lyon area. Finishing gems from Quebec accounted for a third of Parisian exports during the later 17th century, while naturalized porcelain became a major aspect of the Marseillaise economy.

As the skills involved in the production of these manufactures became more and more common, a larger proportion of the French artisan population became dependent on buying from the colonies and selling to the aristocracy. We can see this issue of industries producing for the gentry and the bourgeoisie outside of these cities out of the growth of the high-end wine industries in Bordeaux and Toulouse and the development of the river yacht in Nantes. This, along with laws which empowered the corporations in the cities, strengthened the French economy and helped it become the greatest exporter in Europe from the 1680s to the 1720s.

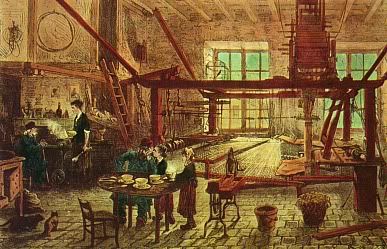

The Lyons silk industry expanded from 500 to 1,500 workers over the 17th century

But while this was a strength in the decades past, the reliance of a few well paid workers making products for a few well paid consumers has become a chokepoint for the development of more important mass production industries. Furthermore there has been intense opposition to the introduction of machines due to the focus on high quality craft goods.

This focus on luxury items underlines another paradoxical problem in the French economy--low labor costs has led to low consumption levels among the poor. The French peasant or proletarian, who pays most of his wages into the cost of rents, bread, and taxes, has never had the money for the finer goods produced in Flandres, Lyons, or Paris. And while the subsequent turn in the French countryside to industry as a means of furthering household income, this has meant two things:

1-It has worsened the general inadequacy of peasant finances

2-Because they are unaware of the necessity of saving, it has led to a situation where a downturn in any one industry leads to province wide effects in employment.

IV. Tolls

Tolls have always been an aspect of France; inter-provincial tolls have been in place since the Renaissance. But they have become a larger problem since Colbert, desperate for funds, allowed for tolls to be implemented at the sub-provincial level towards the development of specific projects. They began in Elsass, the Basque provinces, and Provence and each of these tolls helped fund Vauban’s planned fortresses. But as this was opened up, other towns and cities sent petitions for tolls, and soon France was split into hundreds of toll areas. And while this promoted important infrastructural projects at first, such as the expansion of the Nantes port, the development of paved roads, and the funding of the National Guard, since 1730 and the further expansion of tolls they have become the single greatest enemy to any industrial strategy Paris could conceive of.

Toll regions in France, 1786

Tolls have made the cost of long distance transport insurmountable, and have thus been the eternal opponent to economies of scale and has kept firms too small to benefit from the specialization that Smith argues for. Beyond this, the fragmented nature of the French market has made it impossible for the whole of France to compete with British goods, leaving those provinces who

do directly compete for markets (notably Normandy, Flandres, and Brittany) facing a state of chronically failed industry. And though attempts have been made in the king’s lands before the revolution and in the liberal parliaments of the Gascony and Normandy afterwards to lower or eliminate tolls, most republics have retained the tolls put in place during the Colbert administration.

The tolls also relate to the strength of France’s oldest industry--smuggling. The informal “Smuggler’s Guild”, which specialized not only in shipping goods illegally across borders sans-tolls but also in counterfeit currency and goods, was formed in the decade after the dissolution of the Jansenists and included some of the most nefarious criminals that the world has ever seen. It is rumored that the fortunes of Garcon “Le Chat” de Paris, the fifth leader of the Guild, numbered in the millions of livres, to the degree that he was able to challenge the King’s Faction in the Paris parliament in a proxy war that led to his execution. Furthermore, it has become impossible to do business in many sectors of the French economy without recourse to smuggling. In certain areas of southern France, it is cheaper to import iron from

Russia than it is to use iron from the mountains seventy kilometers away. Under such conditions, the goods suitable for the domestic market are the luxury goods I discussed earlier, whose dramatic price can absorb the frankly ridiculous transportation costs that French policy has imposed on the economy--even if one is moving something which has been supported, like silk, along state roads, transportation and tolls still account for 70% of the cost of manufacture.

The last two issues I have described are economic in their causes and their effects, but the reasons for their continuation is wholly political. The continued survival of three institutions from the Ancien Regime, the guilds, corporations, and provinces, has made any systemic reform of France’s industrial organizations all but impossible.

V. Guilds, Corporations, ‘Republics’

I may be voicing unpopular views to this court today, but I believe that the largest reason for the continuation of these irrational economic policies in our Grand Republic is the survival of provincial power in the form of the Republics, and the strength of guilds and corporations(

1). These organizations, which do not serve the whole of the public but merely the interests of their constituents, lead to a polity which virulently defends unnecessary and economically irrational privileges. In order to move to a more modernized economy, we must bring these elements to heel and strengthen our criminally weak central government.

The issue is that the privileges associated with municipal or provincial rule, and the unearned power that the guilds and corporations have in our society, are both products of specific circumstances which have passed.

Colbert’s desire to help the French economy in the wake of the Olive Oil Crash led to an extra-ordinary focus on both the cities and the colonies as a means of growth. I have noted before that Colbert gave the municipal districts a massive decrease on duties from colonial goods, but that is not the whole of the policy he crafted. In order to sate the unrest brought along with increased production (and, in Flandres, to ease the pain of the province’s split between Amiens-et-Nord and Flandres proper), Colbert allowed a major expansion of the guilds as well as a major expansion of their role in the city governments of Paris, Flandres, and Lyons. The Great Corporations of Paris were unilaterally increased from 12 to 24, and the Flemish Guilds were given their own parliament with equal representation to the King’s decisions and the provincial estates!

(2) The guilder syndics were thus given the authority and respect they felt they deserved, which allowed them to step production up to a large degree.

Furthermore the Syndics set up several trade schools in the skilled fields of weaponsmithing, engineering, and tapestry-making. All of these schools were excellent purveyors of age-old techniques, but as time wore on these became highly conservative institutions. While the tapestry-makers extended their field further into other forms of textiles, they have made sure that such ‘base’ industries as cotton-working and linens stayed out of Flandres, and the weaponsmiths of Bruges still teach their men how to make matchlock pistols!

The ‘pushing out’ of large-scale industry in Flandres, which is still the de facto most industrialized republic of France, is but one example of the highly negative effects that guilder and corporate power has had in France. Each of the guilds, regardless of region, has aided and abetted in

sabotage of new machinery, has attacked the implementation of new techniques, and has further supported the smugglers. It is clear that they feel threatened by the new world we are increasingly stepping towards, and that they will do whatever they can to stop our progress towards that world.

The Parliament of Auvergne voting to retain their tolls

The Republics are just as, if not more complicit in the reproduction of the institutions of the Ancien Regime. The continuation of the tolls in the Federation d’Auvergne was passed almost entirely through the votes of the family of Tours d’Auvergne, who personally collect the taxes levied at the customs houses. We can see other horrid examples of tolls in the Federation du Rhone’s use of them to surround the city of Lyons.

The Founding Father of this Republic, Monsieur de Boheme, has argued that the establishment of localized governance and localized governance is supportive of democracy. Well I say to hell with democracy! These democratic institutions have held our nation back, for no one can consider past their own limited views and consider the interests of the whole of the people, of the whole of our Republic! In summation, I suggest a return to the institutions of the First Republic, and the foundation of a rationalized and skillful bureaucracy to rule the nation in the name of the nation! (3)

1-Note that Guilds and Corporations refer to the same entities; guild is a French transliteration of the Flemish term Gilde, though the two began to have different connotations shortly before the revolution, as the corporations became more dominated by the radical compaignons while the gildes became more powerful in the Flemish parliament

2-Flandres had a unique governmental system under the Ancien Regime. It possessed a provincial estate which was similar, structurally, to the general estates--it had three estates consisting of the 1st estate (clergy), 2nd estate (aristocrats), and third estate (the ‘bourgeoisie’, which in this period had the specific dual meaning of city-dwellers but also meaning the whole of the population). This parliament would not be unique if it weren’t the only one of its kind until the era of the Grande Republique. Beyond this, there was another branch discussed by Saint Simon, the Syndic’s Council, which was elected by all the recognized guilds of Flandres, which was the largest electorate in the world outside of the English Republic even if it was largely limited (metalworkers, for instance, were not represented until the 1740s). The last branch was composed in the office of the Governor of Flandres, who represented the King’s will. This three branch system was largely illusory during the Ancien Regime, the Estates and Governor voted together almost all of the time.

3-This report led to the demotion of Saint Simon to national representative shortly after its release.Marc Bloch was way better...until he got shot by the Gestapo