The German Reich and the Second World War

Europe 1939

Europe 1939

Starting Year: 1936

Country: Germany

Difficulty: Hard (changed to Very Hard mid way through the game)

Version: For The Motherland v3.05

Mod: The Historical Plausibility Project 2.6.62a

Note: All links are in green. This post will be updated, and a new link inserted, for every new AAR related post made.

Table of Contents:

Part I - Prologue

Chapter 1 - Extracts from 'A short history of Germany in the 1930s'

Chapter 2 - Jane’s guide to the German Military, 1939 edition

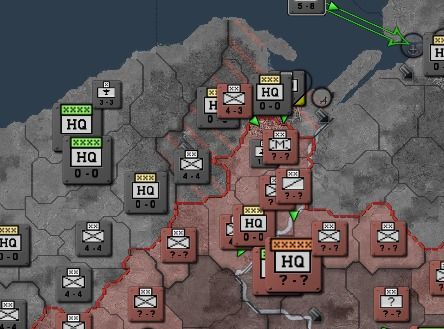

Part II - The Polish Campaign (1939)

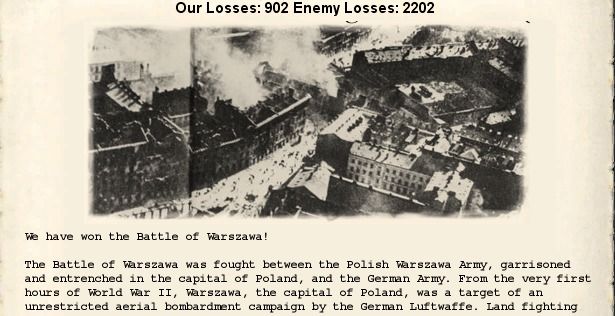

Chapter 3 - Case White

Chapter 4 - The opening days of the war

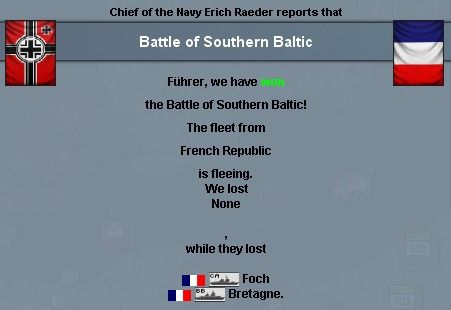

Chapter 5 - The Baltic battles

Chapter 6 - German national newspaper, 26 September 1939

Chapter 7 - The aftermath of the Polish campaign

Part III - The Phoney War

Chapter 8 - German National Newspaper, 17 October 1939

Chapter 9 - Operation Falcon

Chapter 10 - The Falcon Raids

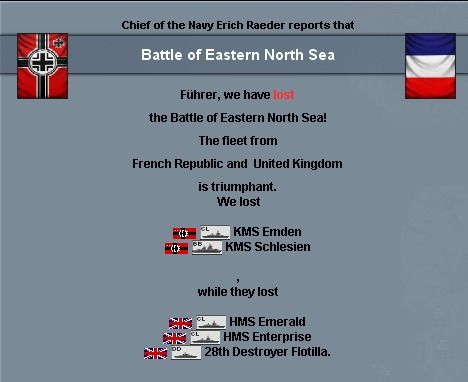

Chapter 11 - Action of 29th January 1940

Chapter 12- The final air battles of the Phoney War

Interlude

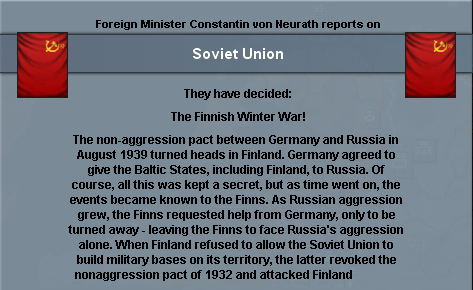

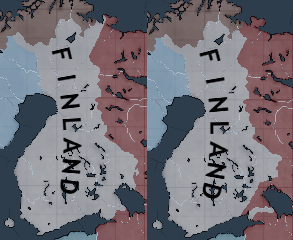

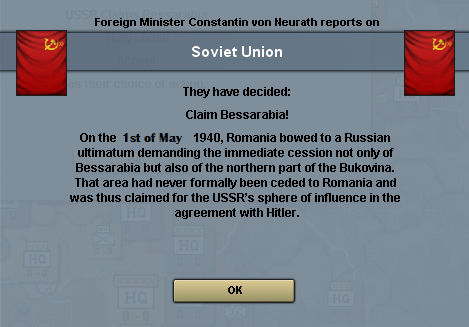

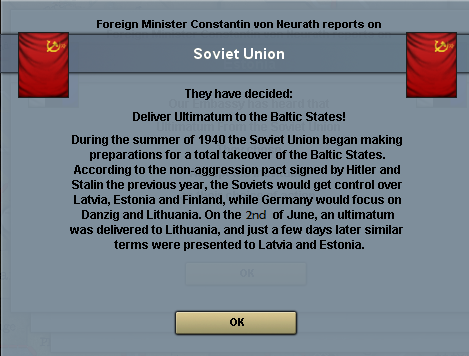

The Soviet Union and the Second World War

Part IV - The Campaign in the West (1940)

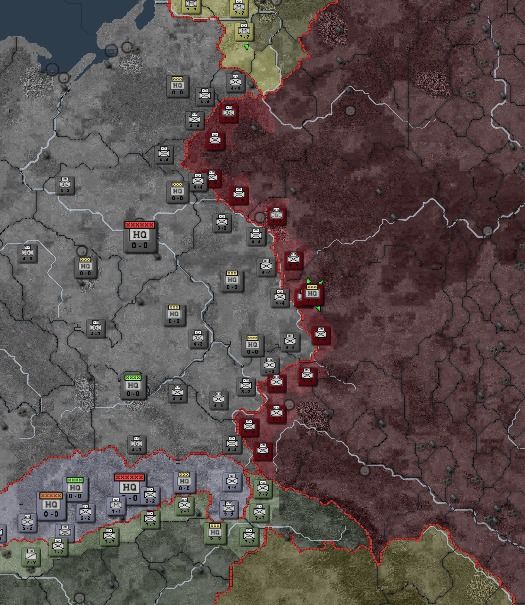

Chapter 13 - Case Yellow

Chapter 14 - Case Orange

Chapter 15 - Case Blue

The Battle of France

Chapter 16 - The battle of the frontier (18-24 May)

Chapter 17 - Panzer advance (25-31 May)

Chapter 18 - Battle of Brussels (1-7 June)

Chapter 19 - Two months in Holland

Chapter 20 - German National Newspaper, 11 August 1940

Chapter 21 - Battle of Hasselt Wood (28 August-20 September)

Chapter 22 - Operation Moltke (11 October - 1 November)

Chapter 23 - The Second Siege of Paris (11-29 November)

Chapter 24 - The Battle of Normandy (5 Dec-1 Jan) and Mopping up

Chapter 25 - The aftermath of the Battle of France

Interlude

Italy and the Second World War

Part V - Sideshows

Chapter 26 - Opening of the Second Battle of the Atlantic

Chapter 27 - The Yugoslavian campaign

Chapter 28 - Sideshows

Chapter 29 - Orders of Battle

Part VI - Case Barbarossa (1941)

Chapter 30 - Case Barbarossa

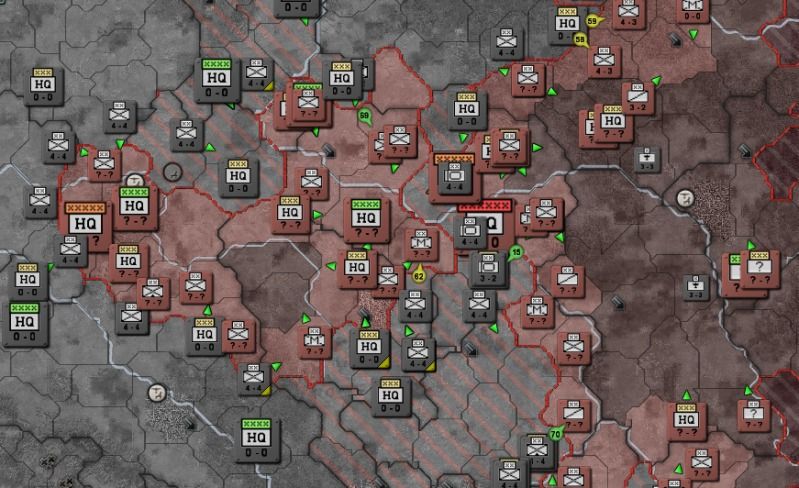

Chapter 31 - June

Chapter 32 - July

Chapter 33 - August: Strategy falters

Chapter 34 - Black September

Chapter 35 - National propaganda newspaper, 17 October, 1941

Chapter 36 - October: initiative shifts

Chapter 37 - November

Chapter 38 - December: another Christmas at war

Chapter 39 - Barbarossa: A retrospect

Interlude

The winter Olympics

Part VII - Case Wilhelm (1942)

Chapter 40 - Case Wilhelm

Chapter 41 - Operation Hoffmann (18 April – 12 May)

Chapter 42 - Exploit and preparation (13 - 25 May)

Chapter 43 - Operation Ludendorff (26 May – 6 June)

Chapter 44 - The Cauldron Battles (30 May – 13 June)

Chapter 45 - The fight continues (15 – 24 June)

Chapter 46 - Operation Hindenburg (25 June – 17 July)

Chapter 47 - A change of Command

Chapter 48 - Operation Paradox (13 - 26 August)

Chapter 49 - The battle of Lake Peipus (6 – 30 September)

Chapter 50 - Operation Paradox stage 2 (phase 3 and 4) (2nd Oct – 10 Nov)

Chapter 51 - Battle for Estonia (10 Nov 1942 – 19 Jan 1943)

Chapter 52 - 1942 in summary

Interlude

The United Kingdom and the Second World War

Part VIII - The winter battles

Chapter 53 - The Rebel problem

Chapter 54 - Fighting in the north

Chapter 55 - The Third Battle of Odessa (24 January – 22 March)

Interlude

World War

Part IX - Case Teutonic (1943)

Chapter 56 - Operation Teutonic

Chapter 57 - The Break-in

Chapter 58 - Mopping up

Chapter 59 - Completion

Chapter 60 - Summing up

Part IX - Case Clockwork (1944)

Chapter 61 - Christmas Planning Session

Chapter 62 - Master of the Dnieper (16 Feb – 28 March)

Chapter 63 - The Battle of Vesele (29 March – 22 April)

Chapter 64 - The Battle for the Crimea (23 April – 5 June)

Chapter 65 - The Battle of Boryspil (21 June – 20 July)

Chapter 66 - The breakout battle (20 July – 20 August)

Chapter 67 - The Battle of Kursk (1 September – 3 October)

Chapter 68 - Intermission and encirclement (4 October – 14 November)

Chapter 69 - The Battle of Kharkov (15 November – 4 December)

Chapter 70 - Operation Clockwork: conclusion

Interlude

The Axis powers and the Second World War

Part X - Case Armageddon (1945)

Chapter 71 - The build-up (Late 1944 - Early 1945)

Chapter 72 - Case Armageddon

Chapter 73 - The Donets campaign (1 March – 10 April)

Chapter 74 - The Alekseevka Offensive (9 April – 21 May)

Chapter 75 - The Moscow Offensive (1 – 26 June)

Chapter 76 - Treaty of Moscow

Chapter 77 - German National Newspaper, 8 July 1945

Part XI - Master of Europe

Chapter 78 - Various communications across the Reich

Chapter 79 - The Romanian Campaign (Operation von Mackensen) 20 September – 24 November 1945

Chapter 79 - Internal security in the conquered territories

Chapter 80 - Operation Magna Mater (10 December 1945 – 28 January 1946)

Chapter 81 - Operation Minerva (29 January – 18 April)

Chapter 82 - Masters of Europe

Interlude

Operation Faust

Part XII - The Battle of Britain (1946)

Chapter 82 - The opening battle (10 May 1946)

Chapter 83 - The Main Assault (12 May - 8 June 1946)

Chapter 84 - Operation Sea Lion II

Chapter 85 - Invasion (16 June – 27 June)

Part XIII - Operation Overlord (1946 - 1947)

Chapter 86 - The Battle of Calais (19 July – 4 August)

Chapter 87 - Victory in France (9 August – 1 September)

Chapter 88 - The next wave (1 September – 22 September)

Chapter 89 - The battles of St. Malo and Carentan (25 September – 6 November)

Chapter 90 - Operation Faust update

Chapter 91 - The Battle of Normandy continues (7 November – 27 December)

Chapter 92 - Winter: 1947 arrives

Chapter 93 - An anthology of OB West communications

Chapter 94 - Stalemate (2 February – 30 April)

Chapter 94 - Construction plans

Chapter 95 - Allied Breakout Offensive (3 – 9 May)

Chapter 96 - Betrayal (9 – 13 May)

Chapter 97 - Withdrawal (14 May – 20 June)

Chapter 98 - Operation Overlord casualty report, 21 June

Interlude

Case Faust

Case Clausewitz

International News, 24 June 1947

Part XIV - The tide turns (1947 - 1949)

Chapter 99 - Battles on the von Rundstedt Line (24 June – 13 July)

Chapter 100 - The July Offensive (4 – 31 July)

Chapter 101 - Withdrawal from the Don River bend (11 August – 28 September)

Chapter 102 - Battle of the Voroshilovgrad - Rostov line (2 October – 4 November)

Chapter 103 - The Italians and the Western Front (5 August – 15 November)

Chapter 104 - Case Bello Gallico (16 – 31 November)

Chapter 105 - Fall of the Regio Esercito (5 - 25 December)

Chapter 106 - Italian Armistice

Chapter 107 - Paulus Offensive (1 January - 19 February)

Chapter 108 - Battle of Neufchatel en Bray (14 – 31 March)

Chapter 109 - Battles of Picardy (1 - 23 April) and Amiens (14-18 May)

Chapter 110 - The von Kleist Offensive (6 – 26 April)

Chapter 111 - The Soviet counterstrike (27 April – 17 May)

Chapter 112 - All quiet on the Western Front (and in the east too) (June – September)

Chapter 113 - Redeployment and planning (September – 31 October)

Chapter 114 - Case Seydlitz (1 November – 31 December)

Chapter 115 - United Nations January Offensive (29 December 1948 – 1 February 1949)

Chapter 116 - Case Büffel Bewegung (31 December – 21 February)

Interlude

Interlude: The Far East and the Second World War

Part XV - Gotterdammerung (1949 - 1950)

Chapter 117 - Battle of Dnieper Bridgehead (8 March – 20 April)

Chapter 118 - Case Derfflinger: planning and preparation

Chapter 119 - Case Bodenplatte II (28 May - 1 June)

Chapter 120 - Vergeltungs Day (5 June)

Chapter 121 - Case Derfflinger: the opening battles (6 – 12 June)

Chapter 122 - The Battle of Italy (13 – 27 June)

Chapter 123 - Case Derfflinger: the fighting continues (17 June – 14 July)

Interlude

Interlude: Notice

Part XV - Gotterdammerung (1949 - 1950) continued

Chapter 124 - Operation Eagle (16 July - 1 August)

Chapter 125 - The Collapse of the Western Front (1 August – 31 December)

Chapter 126 - The end of the Eastern Front (August 1949 - February 1950)

Chapter 127 - The final battles (December 1949 – May 1950)

Part XVI - Epilogue

Chapter 128 - Extracts from 'The Second World War: A statistical study' by a well-known historian

Chapter 129 - Extracts from 'Europe: 1890 - 1960' by a well-known historian

Chapter 130 - Wargames

Europe 1950

Last edited: