SovietAmerika: You said "oh well" to Wood being president instead of Harding, which suggests disappointment about the change, and I'm surprised anyone would prefer Harding over... basically anyone.

Kaiser_Mobius: I left the outcome of the war largely in the hands of the AI. Unfortunately, the AI seemed to pick option_a 100% of the time, regardless of the "ai_chance" line, so I had to turn to... other methods.

Nikolai: Heh, you may have noticed I left it on a rather deliberate cliffhanger. :closedeyes:

Chapter II - Hail to Thee in Victor's Crown - Part V

The army's planned crackdown of the general strike was envisioned to be country-wide in its scope, testifying both the rapidity of the army's recovery from the crushing defeats of 1918 and the extent of working class resentment toward the government due to hyperinflation. The soldiers who marched toward the strikers' barricades in Paris, in Lyon, in Bordeaux, and elsewhere had performed similar actions in the previous two years again and again, and many had grown especially adept at breaking through picket lines and brawling with stubborn workers. Many of these men were veterans of the Great War, survivors hardened by the devastation of battle or embittered by their time in German concentration camps. Many had chosen, often insisted, to remain in the armed forces; as trying as military life was, in many instances it was a vast improvement over the prospect of unemployment and homelessness facing millions of other, discharged men. When hyperinflation destroyed the wage system, army life, with guaranteed rations, shelter, uniforms, and power over others, became one of the most desirable jobs imaginable.

As the army was called in again and again to break strikes, resentment naturally grew. But in many instances, so too did understanding. As much as a soldier might hate a worker for forcing him to use violence to disperse an angry mob, suffering the insults and injuries all in the name of serving France, sympathy was present. In many instances, the people these soldiers were sent against were their family, their friends, or their former comrades in arms. After all, the workers merely wanted a decent wage and a decent life, free of the ineptitude and insensitivity of the government that had lost the war. During the tense standoff in the three days between their arrival and the order to attack, soldiers began fraternizing with the workers, reminiscent of the remarkable Christmas meeting between German and French soldiers in 1914.

It was a scene played out a thousand times all across France. Soldiers would rise in the early morning to the call of their officers. Receiving their instructions to break the strike, the soldiers would form up, marching with weapons at the ready and fixed bayonets toward the barricades the workers set up. Caught unprepared, workers would hurry up to the picket lines, arming themselves as best they could with a hodge-podge of firearms, machine tools, and loose debris. The officers would loudly proclaim the government's order to disperse. A stony silence would follow, soldiers and workers glowering across a no-man's land, brandishing weapons. A second warning would be given, again unheeded. The order to take aim rang up, rifles snapping to attention. A brief pause, then the order to fire. There the story diverged.

In some places, shots rang out. Lined up like a firing squad, the soldiers' fired with deadly accuracy. Workers fell dead and injured, blood flowed. Chaos would erupt as the firing continued with automatic precision. Men and women ran for cover, fighting back as best they could. Soldiers would advance, wielding the bayonet and butt of their rifles to clear away any obstacles. But in many places, too many for any general's liking, the soldiers heard their order to fire and hesitated. The workers might flinch and recoil, expecting the worst, only to be met by eerie silence as the soldiers continued to look down the sights of their weapons. The order to fire would be repeated, in varying degrees of anger and violence depending on the officer in command. Some men turned their guns upon their leaders, others simply put aside their guns and seized their commanding officers, accompanied by the cheers of the stunned and emboldened strikers.

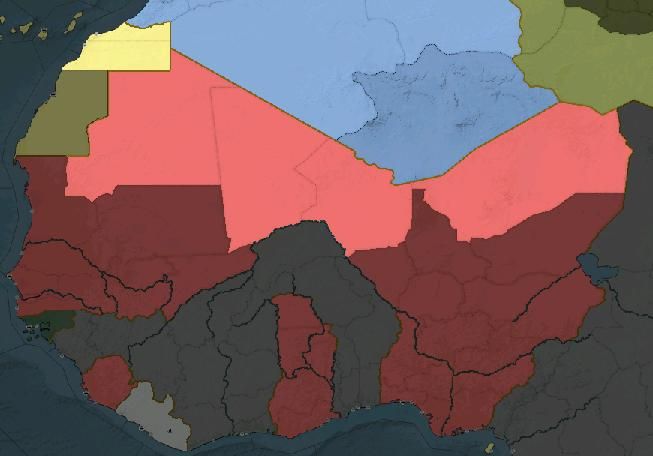

All across France the crackdown unraveled, and pandemonium erupted in Foch's headquarters in Paris. News flooded in at an overwhelming pace. Pitched battles broke out across the country; worker against soldier, soldier against soldier. Some regions were cleared without trouble, while others had gone ominously quiet. Smoke billowed over the cities and great industrial plants of the nation, and gunfire echoed in the air as if it were the Great War all over again. The worst disturbances rocked central France, a thin band running south from the Channel ports to Paris, then across toward Lyon and down to Marseille. By noon of the first day, Foch and Petain knew their plan had backfired stupendously. Instead of a general strike, the generals now faced a revolutionary civil war.

The events that unfolded on March 5, 1921 are too great and chaotic to be recounted here. Fighting continued the next day, by which time opposing forces began to coalesce in organized fashion. The army had fractured into three groups: loyalists battling the strikers and still obeying the high command's orders, the revolutionaries who cooperated with or protected the strikers from attack, and the deserters, who wanted no part in the turmoil enveloping the nation. Paris remained a war zone, but revolutionary soldiers and workers had seized control of Brest, Orleans, Lyon, Marseille, and much of Lorraine. Union leaders, low-ranking officers, and socialist politicians began emerging to bring some sense of organization to the tumultuous, ad hoc revolutionary front. Calls for the overthrow of the 'bourgeoisie' and 'reactionaries' began ringing out and members of the PFC began calling for the formation of a new state along Bolshevik lines. The army in turn appealed to the traditional elements, warning of the destruction of French society if the rebels could not be defeated. Mob-like militias on both sides began to organize around the professional soldiers, and gunfights and shootouts began to grow into full-fledged battles as artillery, armored cars, tanks, and airplanes were deployed to the fighting.

The death toll began to rise, and so too did the level of destruction. Cities already brought to a standstill by the strike were faced with a critical breakdown in basic utilities. Rail lines and roads were closed as armies of rebels and loyalists battled for control of strategic points. Foreign observers would remember piles of garbage and other refuse appearing in the once majestic Parisian boulevards, adding a new stench to the lingering clouds of smoke from recent fighting. But the country was too large and the forces on both sides of this revolution too small for coherent battle lines to be formed. Usually, convoys of soldiers and workers would rush from place to place, claiming control of a city and perhaps deposing any officials or looting badly-needed supplies before moving on. Towns and cities could change hands again and again without a shot being fired, as bewildered farmers and townsfolk looked on passively.

Both the military high command and the newly-formed revolutionary front remained in Paris, determined to personally oversee the outcome of that undecided test. Thus, the course of the turmoil seemed now to rest on the outcome of the battle for the capital. The situation for Foch and Petain, however, was grim. With the transportation network cut off in the chaos and so much of the army already committed to the suppression country-wide, few reinforcements could be spared for the relief of the beleaguered units already present. Paris had been hit heavily by the wave of defections, and only the last-minute intervention of a convoy of armored cars had saved the central districts from being overrun in the first days. But, outnumbered and surrounded, faced with declining morale and overwhelmed by the magnitude of the crisis, it seemed only a matter of time before the government loyalists were defeated.

By March 12, General Foch had begun to lose heart. Underestimating the strength of the strikers from the very beginning, he was unprepared to cope with the scale of the problem facing him. As order broke down, the responsibilities of governing the nation fell more and more on his shoulders, and it was not a task this weary soldier relished. But Petain remained determined to see this through to the end. On March 13, he passionately rejected Foch's suggestions of retreating from the capital and stormed out of headquarters, intent on establishing a new forward command post nearer the front lines. Petain's convoy of armored cars was ambushed along the way and was shot dead trying to break through. The general's death destroyed what was left of Foch's resolve, and he sadly informed Clemenceau that the fight for Paris was lost. The duo escaped the city under cover of darkness for the safety of Calais and the remnants of the British Expeditionary Force still present there after giving an order for all remaining loyalists to retreat as best they could. The flight of General Foch and President Clemenceau left the faltering loyalist resistance rudderless and demoralized. The rebels filled the vacuum they left behind with probing caution. When the magnitude of the loyalist collapse became apparent, the revolutionaries hastily assembled a new provisional government in the capital, proclaiming the death of the corrupt Third Republic and the formation of the French Union.

This new Provisional Government of the Union was a fractious, unsteady affair. At its top, it was dominated by radical leftists of the Bolshevik style, members of the new PCF communist political party. Both the Executive Chairman Zéphyrin Camélinat and Council Chairman Marcel Cachin were members of the communist party, as was the pro-Bolshevik Director of Foreign Affairs Louis Frossard and Director of Public Safety Alfred Rosmer. Tempering these leftist radicals were men of more moderate views, particularly the center-leftist Charles Dumont, former Finance Secretary in 1913, and General Maurice Sarrail, perhaps the only general with outspoken leftist sympathies who had skillfully exploited the chaos as an opportunity to revitalize his career after the defeats of the Great War. But beneath the new executive cabinet was the Workers Council, an amorphous mass people selected from the multitude of unions, soldiers committees, and regional communes, formed in the first chaotic moments of the revolution and largely without organization or qualification to govern but nevertheless convinced of its legitimacy to represent the people of France. Dominated by the CGT, the syndicalist trade union, the prospect of an internal division akin to what had befallen Russia was not out of the question. But, swept up in emotion of this historic revolutionary triumph, the Left remained, for the time being at least, united in this new socialist state.

Kaiser_Mobius: I left the outcome of the war largely in the hands of the AI. Unfortunately, the AI seemed to pick option_a 100% of the time, regardless of the "ai_chance" line, so I had to turn to... other methods.

Nikolai: Heh, you may have noticed I left it on a rather deliberate cliffhanger. :closedeyes:

-----

Chapter II - Hail to Thee in Victor's Crown - Part V

The army's planned crackdown of the general strike was envisioned to be country-wide in its scope, testifying both the rapidity of the army's recovery from the crushing defeats of 1918 and the extent of working class resentment toward the government due to hyperinflation. The soldiers who marched toward the strikers' barricades in Paris, in Lyon, in Bordeaux, and elsewhere had performed similar actions in the previous two years again and again, and many had grown especially adept at breaking through picket lines and brawling with stubborn workers. Many of these men were veterans of the Great War, survivors hardened by the devastation of battle or embittered by their time in German concentration camps. Many had chosen, often insisted, to remain in the armed forces; as trying as military life was, in many instances it was a vast improvement over the prospect of unemployment and homelessness facing millions of other, discharged men. When hyperinflation destroyed the wage system, army life, with guaranteed rations, shelter, uniforms, and power over others, became one of the most desirable jobs imaginable.

As the army was called in again and again to break strikes, resentment naturally grew. But in many instances, so too did understanding. As much as a soldier might hate a worker for forcing him to use violence to disperse an angry mob, suffering the insults and injuries all in the name of serving France, sympathy was present. In many instances, the people these soldiers were sent against were their family, their friends, or their former comrades in arms. After all, the workers merely wanted a decent wage and a decent life, free of the ineptitude and insensitivity of the government that had lost the war. During the tense standoff in the three days between their arrival and the order to attack, soldiers began fraternizing with the workers, reminiscent of the remarkable Christmas meeting between German and French soldiers in 1914.

It was a scene played out a thousand times all across France. Soldiers would rise in the early morning to the call of their officers. Receiving their instructions to break the strike, the soldiers would form up, marching with weapons at the ready and fixed bayonets toward the barricades the workers set up. Caught unprepared, workers would hurry up to the picket lines, arming themselves as best they could with a hodge-podge of firearms, machine tools, and loose debris. The officers would loudly proclaim the government's order to disperse. A stony silence would follow, soldiers and workers glowering across a no-man's land, brandishing weapons. A second warning would be given, again unheeded. The order to take aim rang up, rifles snapping to attention. A brief pause, then the order to fire. There the story diverged.

In some places, shots rang out. Lined up like a firing squad, the soldiers' fired with deadly accuracy. Workers fell dead and injured, blood flowed. Chaos would erupt as the firing continued with automatic precision. Men and women ran for cover, fighting back as best they could. Soldiers would advance, wielding the bayonet and butt of their rifles to clear away any obstacles. But in many places, too many for any general's liking, the soldiers heard their order to fire and hesitated. The workers might flinch and recoil, expecting the worst, only to be met by eerie silence as the soldiers continued to look down the sights of their weapons. The order to fire would be repeated, in varying degrees of anger and violence depending on the officer in command. Some men turned their guns upon their leaders, others simply put aside their guns and seized their commanding officers, accompanied by the cheers of the stunned and emboldened strikers.

All across France the crackdown unraveled, and pandemonium erupted in Foch's headquarters in Paris. News flooded in at an overwhelming pace. Pitched battles broke out across the country; worker against soldier, soldier against soldier. Some regions were cleared without trouble, while others had gone ominously quiet. Smoke billowed over the cities and great industrial plants of the nation, and gunfire echoed in the air as if it were the Great War all over again. The worst disturbances rocked central France, a thin band running south from the Channel ports to Paris, then across toward Lyon and down to Marseille. By noon of the first day, Foch and Petain knew their plan had backfired stupendously. Instead of a general strike, the generals now faced a revolutionary civil war.

The events that unfolded on March 5, 1921 are too great and chaotic to be recounted here. Fighting continued the next day, by which time opposing forces began to coalesce in organized fashion. The army had fractured into three groups: loyalists battling the strikers and still obeying the high command's orders, the revolutionaries who cooperated with or protected the strikers from attack, and the deserters, who wanted no part in the turmoil enveloping the nation. Paris remained a war zone, but revolutionary soldiers and workers had seized control of Brest, Orleans, Lyon, Marseille, and much of Lorraine. Union leaders, low-ranking officers, and socialist politicians began emerging to bring some sense of organization to the tumultuous, ad hoc revolutionary front. Calls for the overthrow of the 'bourgeoisie' and 'reactionaries' began ringing out and members of the PFC began calling for the formation of a new state along Bolshevik lines. The army in turn appealed to the traditional elements, warning of the destruction of French society if the rebels could not be defeated. Mob-like militias on both sides began to organize around the professional soldiers, and gunfights and shootouts began to grow into full-fledged battles as artillery, armored cars, tanks, and airplanes were deployed to the fighting.

The death toll began to rise, and so too did the level of destruction. Cities already brought to a standstill by the strike were faced with a critical breakdown in basic utilities. Rail lines and roads were closed as armies of rebels and loyalists battled for control of strategic points. Foreign observers would remember piles of garbage and other refuse appearing in the once majestic Parisian boulevards, adding a new stench to the lingering clouds of smoke from recent fighting. But the country was too large and the forces on both sides of this revolution too small for coherent battle lines to be formed. Usually, convoys of soldiers and workers would rush from place to place, claiming control of a city and perhaps deposing any officials or looting badly-needed supplies before moving on. Towns and cities could change hands again and again without a shot being fired, as bewildered farmers and townsfolk looked on passively.

Both the military high command and the newly-formed revolutionary front remained in Paris, determined to personally oversee the outcome of that undecided test. Thus, the course of the turmoil seemed now to rest on the outcome of the battle for the capital. The situation for Foch and Petain, however, was grim. With the transportation network cut off in the chaos and so much of the army already committed to the suppression country-wide, few reinforcements could be spared for the relief of the beleaguered units already present. Paris had been hit heavily by the wave of defections, and only the last-minute intervention of a convoy of armored cars had saved the central districts from being overrun in the first days. But, outnumbered and surrounded, faced with declining morale and overwhelmed by the magnitude of the crisis, it seemed only a matter of time before the government loyalists were defeated.

By March 12, General Foch had begun to lose heart. Underestimating the strength of the strikers from the very beginning, he was unprepared to cope with the scale of the problem facing him. As order broke down, the responsibilities of governing the nation fell more and more on his shoulders, and it was not a task this weary soldier relished. But Petain remained determined to see this through to the end. On March 13, he passionately rejected Foch's suggestions of retreating from the capital and stormed out of headquarters, intent on establishing a new forward command post nearer the front lines. Petain's convoy of armored cars was ambushed along the way and was shot dead trying to break through. The general's death destroyed what was left of Foch's resolve, and he sadly informed Clemenceau that the fight for Paris was lost. The duo escaped the city under cover of darkness for the safety of Calais and the remnants of the British Expeditionary Force still present there after giving an order for all remaining loyalists to retreat as best they could. The flight of General Foch and President Clemenceau left the faltering loyalist resistance rudderless and demoralized. The rebels filled the vacuum they left behind with probing caution. When the magnitude of the loyalist collapse became apparent, the revolutionaries hastily assembled a new provisional government in the capital, proclaiming the death of the corrupt Third Republic and the formation of the French Union.

This new Provisional Government of the Union was a fractious, unsteady affair. At its top, it was dominated by radical leftists of the Bolshevik style, members of the new PCF communist political party. Both the Executive Chairman Zéphyrin Camélinat and Council Chairman Marcel Cachin were members of the communist party, as was the pro-Bolshevik Director of Foreign Affairs Louis Frossard and Director of Public Safety Alfred Rosmer. Tempering these leftist radicals were men of more moderate views, particularly the center-leftist Charles Dumont, former Finance Secretary in 1913, and General Maurice Sarrail, perhaps the only general with outspoken leftist sympathies who had skillfully exploited the chaos as an opportunity to revitalize his career after the defeats of the Great War. But beneath the new executive cabinet was the Workers Council, an amorphous mass people selected from the multitude of unions, soldiers committees, and regional communes, formed in the first chaotic moments of the revolution and largely without organization or qualification to govern but nevertheless convinced of its legitimacy to represent the people of France. Dominated by the CGT, the syndicalist trade union, the prospect of an internal division akin to what had befallen Russia was not out of the question. But, swept up in emotion of this historic revolutionary triumph, the Left remained, for the time being at least, united in this new socialist state.