Who cares about infamy? Just make sure you're scary enough, and everybody will leave you alone.

Novum Romanum Imperium 2.0 -- a Vicky 2 AHD Conversion AAR

- Thread starter Avindian

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

And what about create some kind of decision which gives you cores in Germany (or even all Europe) in a similar way to Manifest Destiny does for the USA?

It could be justified with your story or some other stuff you think... and this way infamy will reduce a lot without avoid wars

It could be justified with your story or some other stuff you think... and this way infamy will reduce a lot without avoid wars

Who cares about infamy? Just make sure you're scary enough, and everybody will leave you alone.

Agreed. Read MorningSIDEr's Sokoto AAR if you want proof.

Actually, It'd be interesting if the North German Fed expanded from Lubeck and added all those German minors.

First, it'd give some clean borders and get rid of those minors, second, it'd generate another possible antagonist, and third, Bismarck and Co. might as well switch to them, which would make diplomatic relations really interesting

First, it'd give some clean borders and get rid of those minors, second, it'd generate another possible antagonist, and third, Bismarck and Co. might as well switch to them, which would make diplomatic relations really interesting

Who cares about infamy? Just make sure you're scary enough, and everybody will leave you alone.

Agreed. Read MorningSIDEr's Sokoto AAR if you want proof.

My standing house rule is not to break the infamy limit. (Although MorningSIDEr's AAR is excellent!) It's not a question of "Can I do it?" so much as "Is it fair and not too gamey?"

And what about create some kind of decision which gives you cores in Germany (or even all Europe) in a similar way to Manifest Destiny does for the USA?

It could be justified with your story or some other stuff you think... and this way infamy will reduce a lot without avoid wars

That might be feasible, but I lack the skill to create such a decision. If a reader wants to help me out with this, I'll consider it.

Actually, It'd be interesting if the North German Fed expanded from Lubeck and added all those German minors.

First, it'd give some clean borders and get rid of those minors, second, it'd generate another possible antagonist, and third, Bismarck and Co. might as well switch to them, which would make diplomatic relations really interesting

This would be the best of all possible worlds, in my opinion. I'm toying with allying the NGF, if the engine will let me, once 1885 gets here and I can play again.

That might be feasible, but I lack the skill to create such a decision. If a reader wants to help me out with this, I'll consider it.

If you could upload the text of the Manifest Destiny decision I could do it. It is only that this month I am not at home so I have no access to the game, but it is very easy. :blush:

If you could upload the text of the Manifest Destiny decision I could do it. It is only that this month I am not at home so I have no access to the game, but it is very easy. :blush:

I may do that when I get home; in any case, it's no big deal, since I won't be able to play for a while anyway.

I may do that when I get home; in any case, it's no big deal, since I won't be able to play for a while anyway.

As you want, in any case the story would be great, I am sure

As you want, in any case the story would be great, I am sure

+10 for Motke, that idiot Cyrus had it coming!

Thanks for the kind words!

Chapter 15: The rise of the Socialists

Note: This update begins a few minutes after the last one ended; you may want to read the last portion of that update to get caught up.

26 November 1868, office of the military correspondent of the Roman Times, Rome

Arturo Orsatti, the Minister of Security, could hardly control his laughter. Michele Zinna, the military correspondent, had been a private in Arturo's squad right after Arturo became a Lieutenant; even then, he'd been a jokester, and Arturo made sure that Zinna had gotten promoted whenever he did. Zinna never quite made officer, since not everybody appreciated his jokes, and he'd lost his right leg in a battle. That meant he was discharged from the army, but while being a great storyteller might have been a liability for some in the army, he made a fantastic journalist. A timid knock on the door interrupted their revelry. Zinna rose to answer the door. "Lieutenant! I am so sorry; I must have lost track of time. Minister Orsatti, a pleasure as always."

The Minister shook Zinna's hand and turned to leave, but stopped for a moment on the way out the door. "It's Marković, right?"

The sailor who'd just entered nodded. "Yes, sir. Nikolai Marković."

Orsatti opened his briefcase and handed the Lieutenant a file. "I think you'll be interested in what this has to say. One of my agents got this from Sarajevo. A hero should have a name, don't you agree?" The Minister of Security smiled cryptically and left.

Nikolai, remembering his manners, fought to open the file and put it under his chair. He looked up at Zinna, who had a pad of paper on his desk. "Sorry, Mr. Zinna. I'll look at this later."

Zinna shrugged. "If you want to look now, I can wait. There might be something good in there for your story anyway."

"Are you certain?" Zinna nodded; that was all the excuse Nikolai needed to tear open the file. As he read the first page, his eyes grew wide.

Name: Alekseyev, Nikolai Bogdanovich.

Birthplace: Sarajevo, Bosnia provincia

Date of Birth: 19 March 1840

Father: Alekseyev, Bogdan Sergeyevich, Russian diplomat, based in Sarajevo. Born 5 September 1780 in Vladimir, Russian Empire, died 15 October 1839 in Sarajevo of natural causes.

Mother: Alekseyeva, [last name before marriage unknown] Nina Andreyevna, Bosnian prostitute. Born 19 July 1791 [birthplace unknown], died 19 March 1840 in Sarajevo of natural causes, childbirth related.

Recorded date of marriage: 1 August 1838.

Notes on subject: Belongs to Jacobin revolutionary cell based in Palermo. Date of membership unknown. Fluent in many languages, skilled in hand-to-hand combat. Primarily an assassin; 10 confirmed kills, more suspected. Currently assigned to target Guillermo di Marco. Agent 5679-9048 (Alessandro, Cristoforo) will pose as di Marco's son. Second to navy for duration of assignment. Orders: Gain confidence of subject Alekseyev. Ascertain means and method of assassination. If possible, recruit Alekseyev; subject is not an enthusiastic Jacobin and may be willing to defect.

The remaining pages in the file contained almost every single activity Nikolai had participated in since his birth. His father was already under surveillance, as were all Russian diplomats at the time of the civil war, according to the file. A past. It may be sordid, but I have a past, for the first time! Before Nikolai closed the file, he noticed a handwritten addendum on the last page.

Subject is enlisted as a naval officer as of 1864. Further surveillance is terminated. Relevant biographical data will be forwarded to Marshal's office for entry; all other records are marked for deletion. -- Arturo Orsatti, Minister of Security.

He gave the file to me, but ordered it destroyed, so it would be removed from the records. He has done me a great kindness. I have a proper name now, and a father to be proud of!

Zinna waited until Nikolai put down the file. "Did you learn what you needed to?"

Nikolai grinned and nodded. "I'm ready, sir."

"Wonderful. Please state your name for the record."

"Nikolai Bogandovich Alekseyev. Lieutenant, Roman Navy."

Zinna raised an eyebrow, but continued with his questions. "Our readers are somewhat familiar with your history; Minister Orsatti briefed me on what I could say and what I could not. Let's talk about your assassination."

For a brief moment, Nikolai froze. Then he caught his breath. The assassination of me, not by me. "Well, sir, I'd hardly call it an assassination, as I appear to be breathing."

Zinna laughed at that one. "Very good, Lieutenant. Your attempted assassination."

Nikolai did his best to remember what happened. "Let's see. The Admiral caught my attention. He wanted me to interview one of our Mexican prisoners. I remember somebody grabbing me, whispering something into my ear, and then he stabbed me three or four times."

Zinna checked his notes. "According to one of the officers on the Da Vinci, it was 'True Jacobins do not fail in their tasks.'"

Nikolai shrugged. "That could be. I was sort of preoccupied, you understand."

The journalist smiled, then went to his next question. "Did you recognize the person who attacked you?"

"No. But then, I wouldn't have. Discipline within the Jacobins is very strict; I didn't even know the names of the people in my own cell, apart from my direct superior, and he's already been arrested. His Latin was perfect with no accent, which means he's educated; probably a native Italian, although not necessarily. Most Romans speak Italian in their everyday lives, as you well know." Zinna gestured for Alekseyev to continue. "He was taller than me, although there aren't many who're shorter. Other than that, I have no idea."

"What happened next?"

Nikolai smiled faintly. "The idiot tried to throw me overboard, into a boat he had. Unfortunately for him, my leg caught on some netting. A couple of sailors saw me go over and pulled me back up. They fired at the boat a couple of times, but he'd already gotten away. The Admiral decided he wanted the Jacobins to think I was dead, so he hid me below decks for a while."

Zinna whistled in appreciation. "Smart guy, the Admiral."

"When the Da Vinci returned to Rome, they left me in Jamaica. The Admiral wanted to make sure that I was going to be safe, and so he had me work at the naval base there. I was there until February of 1866. I was promoted to Lieutenant by the base commander and was attached to a supply ship going to provide food and supplies for our soldiers in Mexico."

"Sounds relatively normal, but you washed up in Houston in" -- Zinna checked his notes thoroughly -- "June of '66. What happened?"

Nikolai laughed. "A storm. A simple storm. I got pitched over the side and must have hit a rock or two. I have some luck." Zinna laughed too, then Nikolai went on. "Next thing I know, it's August of '66. I start to remember everything a couple of months later, but by then, I've 'joined' the army. I stayed there until the peace was announced, and now I'm here."

Zinna sat back in his chair and paused for a few moments. "That is one hell of a story, Lieutenant. I think you'll be on the front page, for sure."

Nikolai gasped. "You think so?"

"Definitely. Anyhow, it was nice to talking to you, Lieutenant."

Nikolai shook Zinna's hand and made for the rail yard. I've got to get to Palermo so I can get back on a ship. Who knows when war might break out again?

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

16 December 1869, office of the Minister of Security, Naples

Arturo Orsatti threw the newspaper down in disgust, and called for one of his deputies. The first to answer was James O'Connor.

"James, why in the hell do I keep reading this stuff in the papers?"

O'Connor was an easygoing sort, and in most cases would have made a quip and shrugged, but his boss looked angry. "We're doing the best we can, boss, but we don't have enough people with the Jacobins."

Arturo swore and threw some papers on the floor. He eyed O'Connor, who looked properly cowed. James had been part of the Foreign Ministry as a clerk for quite a while, and had gradually worked his way up. Of course, unbeknownst to his superiors, he was also an agent for the Ministry of Security. His job at the Foreign Ministry had been to analyze diplomatic correspondence to see if they could find Jacobin strongholds overseas. James had done fairly well -- he was instrumental in shutting down a cell in Puerto Rico -- but ever since Bismarck became Foreign Minister, he'd had access to less and less data. For whatever reason, Otto didn't trust James, and so Arturo had recalled him. James was now #2 in the Roman ministry as First Deputy Minister, although many of the Station Chiefs -- the departments were renamed to "stations" a few weeks earlier -- had more seniority.

Arturo glared at O'Connor for a few more moments, then surprised his deputy by sighing audibly. "I would give a lot to know who was the head of the Jacobins here in Rome. I truly would."

James nodded sympathetically. "So would I, sir."

"Hand me the military updates, if you would."

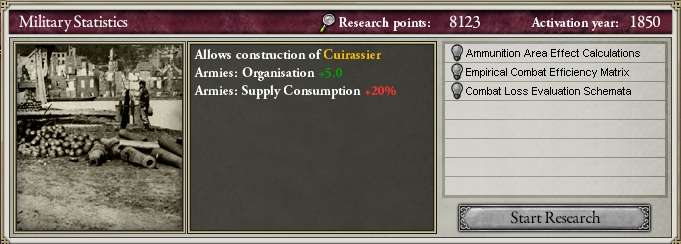

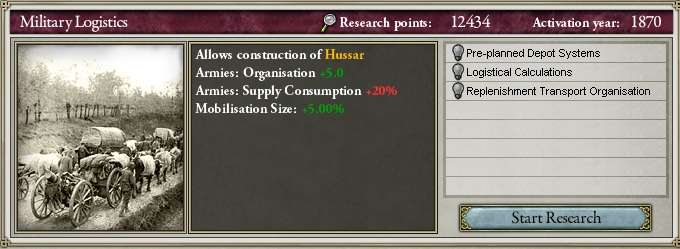

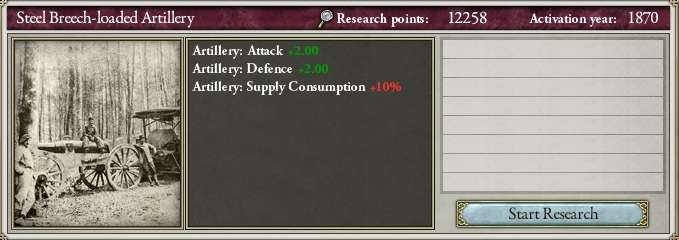

James handed over a sheaf of papers. The most recent trend had been improving supplies to the legions; a new system of Military Plans had just been completed, with the distribution of the breech-loaded artillery to all regiments have been finished in January. The next step was firming up Statistics, so that the quartermasters could get the right supplies to the right troops at the right time.

Arturo scanned the rest of the pages without too much incident -- the official promotion of Nikolai Alekseyev to Lieutenant Commander made him smile -- and then asked James directly for the foreign news.

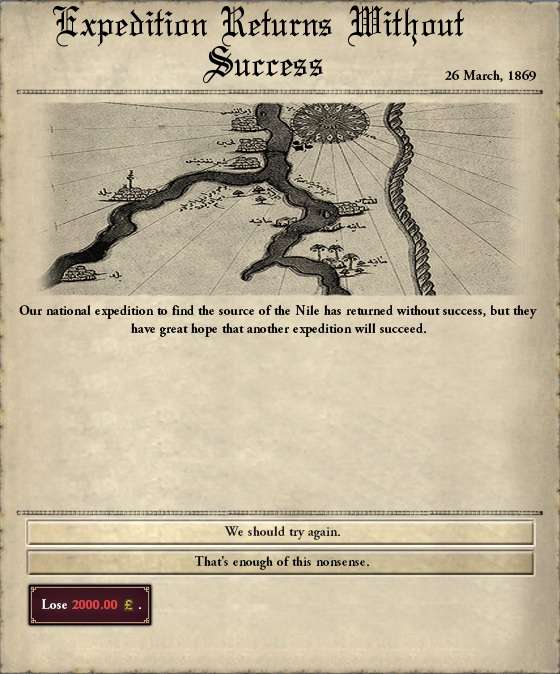

"First, our expedition to the Nile has had no luck. Thankfully, they returned without incident, but they've already requested more funding from the Senate."

Arturo scoffed. "2000 £ is a trifle; I'm sure the Senate will agree."

James nodded in agreement. "Moving on to recent conquests, Norway has taken Greenland and Iceland from Hamburg, Mexico has taken parts of Indiana, Tennessee, and all of Kentucky from Newfoundland, and German Pan-Nationalists have taken over in Bavaria."

"Have we stopped their intrusion into our territory at Linz?"

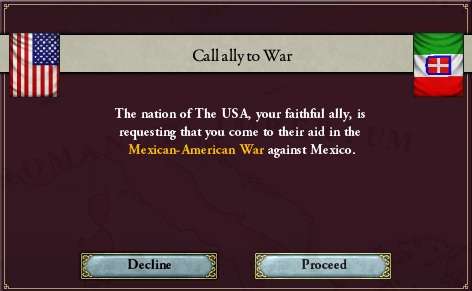

"Yes, sir. The Americans have also proclaimed that their 'Manifest Destiny' is to claim all land up to the Pacific. This will surely lead to war with Mexico."

"Which means we'll get called in." Arturo groaned. "First the Russians use us for their ambitions, now the Americans. When will they help us?"

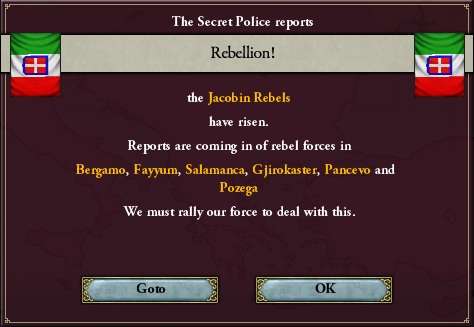

"I'm sure I don't know, sir. I do have a thought on to why there was a Jacobin rebellion recently, however."

Arturo looked at his deputy with a little more respect. "Go on."

"This." O'Connor tossed a newspaper on the desk.

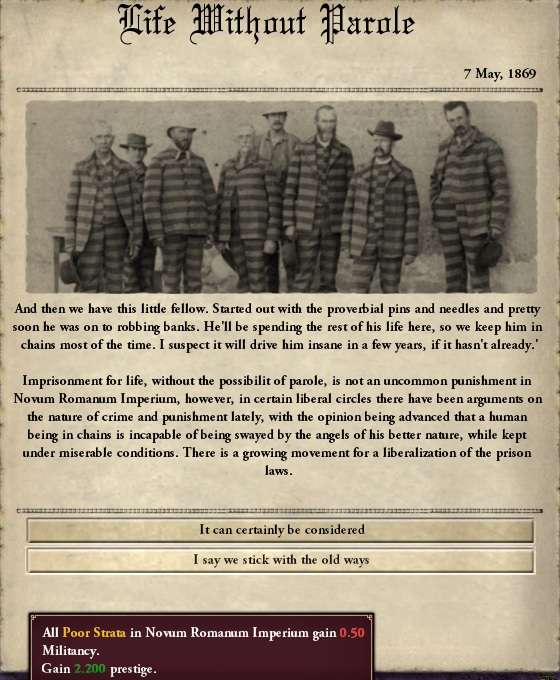

"I signed that order myself, James. These criminals must be kept in seclusion from good, hardworking members of society. Otherwise, how can we protect our citizens?"

O'Connor, being of a more liberal bent, thought carefully before responding. "Is it not better to rehabilitate than to punish? We might convert some of these criminals into productive citizens if they are given the chance for freedom."

Orsatti was unconvinced. "Men will do much for freedom, that is true, but one thing they will especially do is lie."

James considered pushing the point farther, but realized he was unlikely to get anywhere. "Perhaps you're right, sir. Is there anything else?"

"Not for now. Send orders to the legions to drive out these rebellious fools as quickly as possible."

"Yes, sir."

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2 January 1871, office of the Marshal, Florence

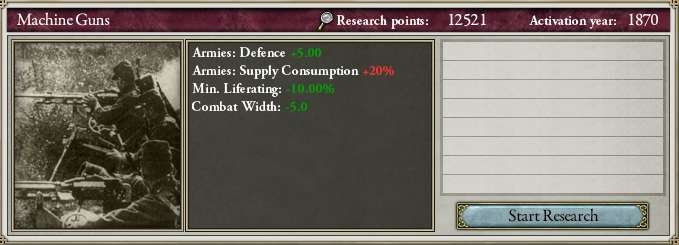

Trajan looked with satisfaction at the newest model of the Roman machine gun.

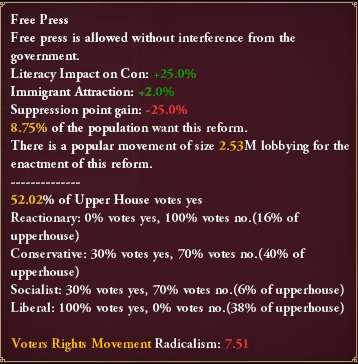

He was less happy that the newspaper from the day before had a detailed expose on the machine gun and its capabilities. This stuff should be kept quiet! It's that damned 'free press' law the Senate passed. There's no more office of Censorship!

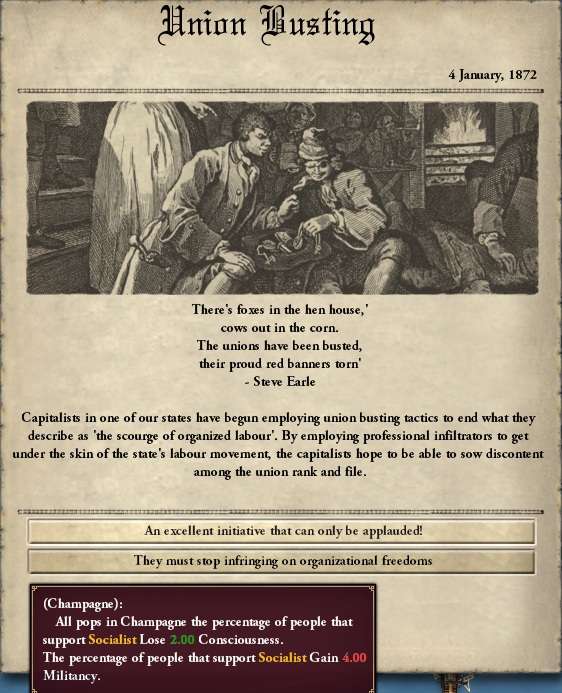

The Free Press Law, enacted by the Senate on 27 October 1870, was a reaction by some of the Agricolares, who'd been waiting for a chance to push this particular issue. The announcement of a second failure to discern the source of the Nile had generated a lot of anger; even though the sums were immaterial, the socialists continued to demand that the money was surely being misspent, and therefore that a proper accounting should be made, in public.

A second, smaller, Jacobin rebellion and a popular rumor that the excavation efforts in Egypt were 'cursed' convinced the conservatives and liberal to go along with it. For once, Bismarck and Trajan agreed on the issue, but it came to nothing.

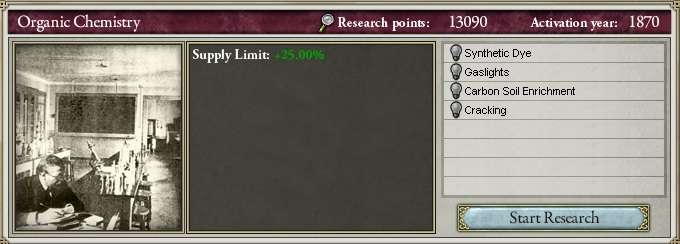

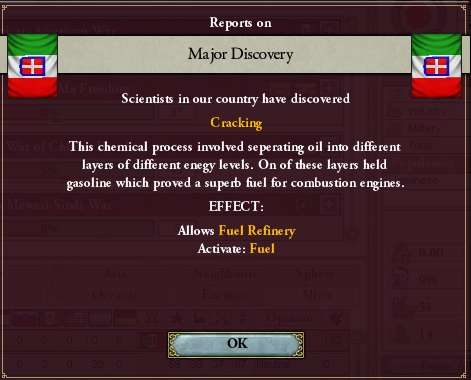

The very first article penned by a socialist in the Roman Times -- he'd signed his name only as "Scriba", or "scribe" -- insisted that funds stop being provided to the "overly large and authoritarian army" for new "tools of repression." Instead, the author exhorted new efforts be made in organic chemistry; well-lit streets would reduce crime, while more efficient fuel could make machines much more efficient.

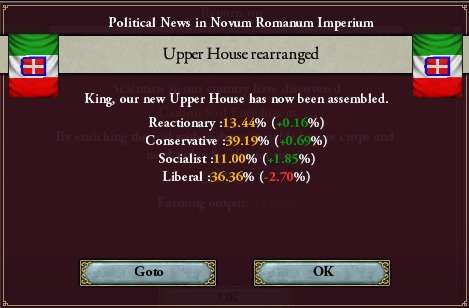

Trajan knew some of these discoveries had military implications too, but he'd been hoping for a new, modern cavalry corps. To Trajan, it just wasn't fair. The smallest faction in the Senate had far too much power, and with support by the liberals and even some conservatives, there was really almost no contest. As a member of the Imperial family, Trajan had no official faction affiliation, but he did have an institutional affiliation, and the socialists were his biggest threat, as he saw it. Trajan scanned the newspaper for the official results from the previous day's election.

Liberals: 40 seats

Conservatives: 39 seats [20 Pecuniares, 19 Militares)

Reactionaries: 14 seats

Socialists: 7 seats

Trajan grimaced. His brother had warned him that, if the Socialists got 10 seats, he'd have to give them a spot in the cabinet. Right now, the cabinet had one Protectores (Bismarck), two Pecuniares (Vickers and Disraeli), one Militares (Orsatti), and two Provincares (J.S. Mill and Cato). If Trajan did have a faction, he'd be Militares. That meant that the three largest parties controlled the cabinet, as it should be. Trajan liked most of his fellow cabinet members, except Disraeli (too formal) and Bismarck (too crazy.)

Even Bismarck at his craziest was better than a socialist; that was Trajan's worst fear.

A fear that might come to pass.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

21 November 1871, deck of the Da Vinci

Lieutenant Commander Nikolai Alekseyev didn't have an official role on his ship. He had plenty of sea duty, but hadn't really displayed any aptitude for any particular job. He was a naval officer whose best skills were writing and hand-to-hand combat; the navy had plenty of use for the former, but not the latter. Unfortunately for Nikolai, communications at sea was still handled by flags and signal lanterns. Eloquent writing in multiple languages was not a requirement for such communication. The XO typically used Nikolai wherever he was short handed, to get him experience at working at multiple duty stations, so at the moment, he was in charge of gunnery. Nikolai wasn't a great mathematician, so he relied heavily on his subordinates to get the job done, like any good officer.

Nikolai observed from the main gun as yet another Roman ship sank into Galveston Bay. "Gunny, why can't we hit the Mexicans?"

The gunnery sergeant spat over the side. "Sir, it's the Commodore in charge of the wooden ships. He insists they can still be useful, but the Mexicans are eating them alive. They're blocking our fire -- we'd be as likely to hit them as we would the enemy -- and so we have to stay quiet."

Nikolai swore in frustration. Like a lot of Romans, he resented the fact that the Romans were pulling the heaviest duty at sea in this war against Mexico. The Americans had fine infantry, which was good for them, but that wasn't very helpful when ship after ship got torn apart by coastal artillery and the Mexican navy.

The upside of this was that Nikolai didn't have much to do. He had his men run a drill and left them in the capable hands of the gunny while he went to the wardroom to report for his next assignment. He saluted the XO as he entered.

"Afternoon, Nikolai."

The XO was a British gentleman from Leeds named Thomas Wilson. "Afternoon, Tommy."

"Heard about the latest expedition to the Nile?" Nikolai shook his head. Tommy grinned. "It looks like we finally made it."

Nikolai let out a small cheer, and was about to reply, when the Admiral walked in. Roberto Filomarino, from Corsica, didn't really talk so much as growl his orders. "Gentlemen, have no choice but to retreat. We're going to Port Charles for now. Wilson, go talk to the communications officer and have him signal the rest of the fleet. Alekseyev, you'll write up the official report. I want it on my desk by the time we reach land."

Both officers nodded. After the Admiral dismissed him, Nikolai went to the wardroom and began to write. The navy had suffered a blow, to be sure, even if the losses were all wooden ships.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

18 May 1873, Imperial Palace, Rome

Emperor Constantine XII smiled as he read the letter from Prince Ferdinand. Ferdinand was 15 now, old enough to formally begin his duties in Constantinople, and he was writing almost every other week about the new sights and sounds. It was good to feel secure, with two sons of his own and Trajan's wife -- the daughter of the American President, Nellie Grant -- was also pregnant. The Farneses would rule, God willing, a while longer. With that thought, Constantine's smile faded. Perhaps I should say 'Mob willing.' The costly defeat at Galveston Bay had provoked a bitter reaction from the people of Rome, who were furious that Rome was fighting America's battles. The massive expenditures in the army and navy -- two corps of seven brigades each of Hussars for the army and a new fleet for the Caribbean, composed of 20 ironclads and 10 monitors -- hadn't helped either. The legions were getting the bulk of research funding, despite critical advances in civilian technology, such as Cracking.

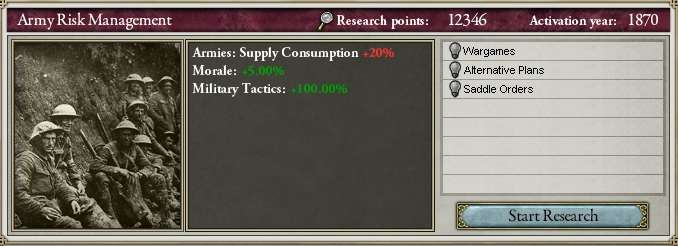

The army's major research programs -- the Hussars and a more systematic program of risk management -- attracted a great deal of resentment, especially when so many Romans either didn't have jobs or were paid insufficiently.

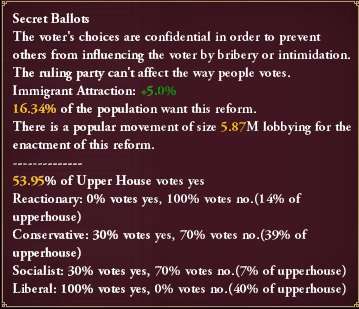

The Senate had voted for a controversial program of secret ballots for elections, but that wasn't enough. The socialists started to agitate more and more.

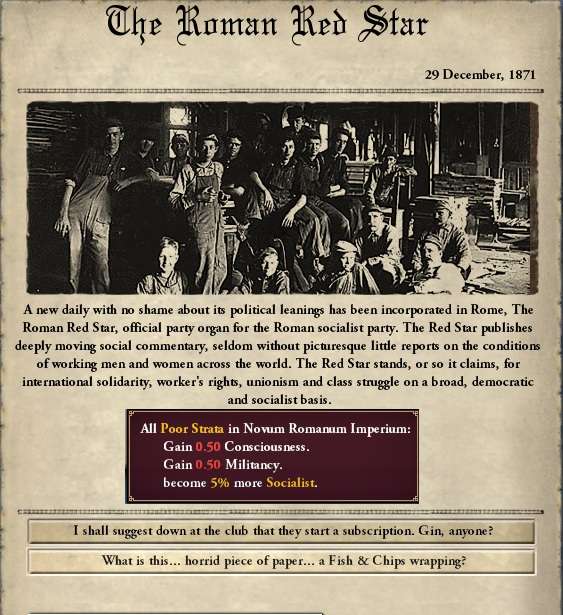

When no government aid was forthcoming, the socialists formed their own newspaper, the Rubrum Astrum, or "Red Star." The editor -- who went by the name of Veritas, or "truth" -- started his new paper with a bang, decrying the violent breaking up of trade unions by Roman legionaries.

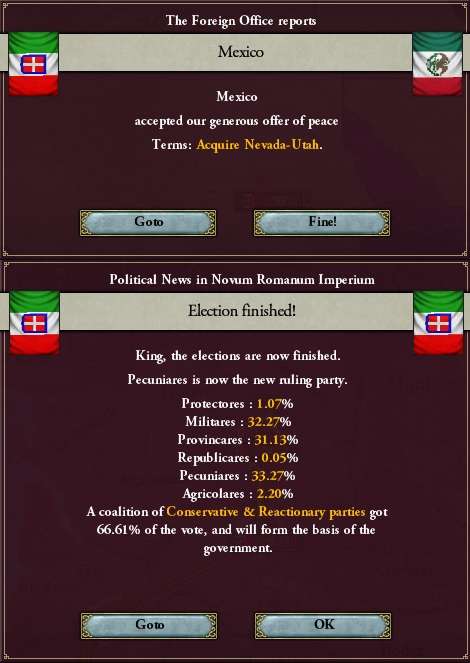

In January of 1873, the Socialists totaled nine seats in the Senate. If not for the seizure of Houston a few days later, and Mexico's capitulation in the war, the Senate might have won an impressive victory in the May elections that determined who would be Chancellor.

As it was, the socialists were a small but loud minority in the Curia. As Chancellor Disraeli had guessed, most of the farmers and soldiers turned out to be conservative, which prevented the socialists from naming their own Chancellor. Even better, the Agricolares could fairly be excluded from the government. There were no cabinet changes, which did please Constantine, who favored stability more than anything.

The only question was, how long would he have it?

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

That's it for another update. I may try to get another one done later this week, so keep your eyes peeled!

Sounds like you got a beating at the hands of the Mexicans. Good to see that someone can still pose a challenge to the mighty Novum Romanum Imperium.

I'm enjoying your story development as always.

I'm enjoying your story development as always.

USA finally breaks up Mexican authority some? Yay.

Of course, Nevada-Utah is nowhere near the rest of US territory, so it might be more trouble than it's worth.

Sounds like you got a beating at the hands of the Mexicans. Good to see that someone can still pose a challenge to the mighty Novum Romanum Imperium.

I'm enjoying your story development as always.

They were mostly wooden ships. I won a number of smaller engagements (1-3 Mexican ships sunk), but that one did kind of hurt. Some of those ships were (technically) 300+ years old!

Go German Pan-Nationalists, go!

Bavaria gone, a few hundred to go

Sorry to burst your bubble, but the Pan-Nationalists decided to visit the Roman Empire and they did not much enjoy their stay.

Interesting stuff - shame about the Mexican reversal. Personally I think Vicky 2's naval mechanics weigh too heavily on quantity over quality. Hell, with enough Clipper Transports you can take on the Royal Navy, apparently you drown them in burning wreckage.

Interesting stuff - shame about the Mexican reversal. Personally I think Vicky 2's naval mechanics weigh too heavily on quantity over quality. Hell, with enough Clipper Transports you can take on the Royal Navy, apparently you drown them in burning wreckage.

Eh, we'll press on

Chapter 16: For the Empire and Labor!

1 January 1874, office of the Roman Red Star, Paris

The celebration continued throughout the newspaper's office as results continued to come in. Several journalists saluted the paper's motto -- Pro Imperium et Laborem -- with their glasses. The editor chuckled to himself in satisfaction.

"For the Empire and Labor, indeed."

The editor, once known anonymously as "Scriba", was no longer anonymous. Iosif Stavros was born in Corinth, but like most Greeks of education and ambition, moved to Constantinople as soon as he was able. Unlike most members of the Agricolares, He was hardly a farmer born and bred -- his father was a very wealthy banker; his mother, distantly related to the hero Constantine Graecus, which gained Iosif the patent of nobility that enabled him to run for the Senate. He'd studied history and languages at the University of Constantinople, but it was his work during a summer recess that gained him the notoriety necessary for a political career.

Iosif, bored with his studies, spent one summer on a farm just outside the city for some extra cash. Stavros, although certainly privileged, had no qualms against manual labor, and he was trying to impress a pretty classmate with his manliness. What he found was his first socialist experience. Some of the laborers were furious with the owner of the farm, who had repeatedly denied them the funds to build a new barracks because "there was nothing wrong with the old one." Given that said barracks had half a roof, no plumbing, a dirt floor, and 10 beds for fifty laborers, Iosif didn't find the complaints all that unreasonable. The farmers, mostly illiterate, begged him to discuss the matter with the landlord. The landlord, at first respecting Iosif's pedigree and eloquence, quickly dismissed Stavros's demands. He fired Iosif the next day, as well as the small group that had asked him to argue on their behalf. At that very moment, Iosif's interest changed to the law, and his first case after graduating was a lawsuit against the greedy profiteer. The farmers got their barracks. This act of generosity garnered him notice among a small group of socialists in Constantinople; he moved to Paris shortly afterwards to be at the faction's headquarters, constructed on the largest grain farm in the Empire, near Paris.

Stavros believed in democracy very strongly; unlike some of the more violent members, he preferred to use political pressure and to win legitimacy through elections. The Red Star was his crowning glory, and he'd broken the story on Rome's attempt to annex part of Bavaria.

Stavros also wrote articles condemning even more funding for military expansion. His article on the new steel breech-loaded artillery was particularly venomous and scathing, citing an army spokesman who'd admitted no real need for new artillery so quickly after the last distribution of weapons.

His greatest triumph, however, was using his paper's growing influence to convince a number of wealthy Romans to vote socialist. He didn't even have to promise anything -- he simply stood by the principles he always had, and with his father's generous support, socialist support grew substantially. His reward? To become the first member of the Agricolares to hold a cabinet seat, with 11 seats going to the Socialists in the recently concluded elections.

Stavros really wanted the Foreign Ministry, or more specifically, wanted Bismarck out of it. He was unsuccessful. Instead, he was offered the Ministry of Education; Mill was one of the Senators defeated in the election, and he hadn't devoted much time or energy to his job. Stavros accepted the post with all the dignity it deserved; he was scheduled to leave for Rome at the end of the week. He was bound and determined to change the system in Rome, to win concession for workers all across the Empire, and to put an end to the constant wars the Empire was engaging in.

Maybe he wouldn't do it overnight, but Iosif Stavros was a patient man.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

7 June 1874, floor of the Senate, Rome

The first major victory for social reform would come from, of all places, the Protectores. Bismarck's pending war with Bavaria had a lot of people thinking about the army, which was how Stavros was able to convince the Senate to hear the pleas of a wounded old soldier from the war against Mexico. As the soldier bemoaned his injuries and the lack of adequate pay, many Senators cried, but one did not. Commander Nikolai Alekseyev, newly elected Senator from Sarajevo, looked with distaste at the veteran. Alekseyev was elected in absentia once the story of his heroism and fascinating history were printed in the Roman Times, which earned him a promotion and the patent of nobility that came with it. He was scheduled to be the executive officer for the new ironclad Italia, although some boiler problems kept the fleet in Rome for the moment.

Alekseyev begrudged none of his fellow servicemen their time in the Senate, and even agreed with the general idea of social reform. He was a registered member of the Militares, but his rather poor background made him sympathize with the Agricolares. This particular veteran, however, was no hero in Nikolai's eyes. He was, in fact, a deserter. His "glorious wound" had come when he'd tried to sneak off his post in Houston, only to be shot by a Mexican soldier. Nikolai didn't think that Stavros knew the veteran's background or his disgraceful conduct, but that made the example no less damning.

The worst part was, Nikolai knew that there were only two options. A number of prominent middle class businessmen -- mostly Pecuniares -- had proposed a minimum wage in the Curia. Disraeli brought this option to the Senate, but did it for his own purposes. The Provincares, in particular Spurius Porcius Cato, had forced through a bill which ended all subsidies in the Roman Empire, arguing that these subsidies were crippling the economy. When coupled with a tax cut -- the rates for poor, middle class, and rich were now 15%/25%/35% -- the bill passed with a huge majority.

Disraeli quickly recognized that this would generate unemployment, and given how much he relied upon conservative farmers and workers in the Curia, argued for the minimum wage to keep his constituency together. The Protectores, ever interested in crippling their foes and gaining a share of the most reactionary members of the Militares, proposed instead pensions for the elderly and disabled. Bismarck was no more a worker's rights advocates than Disraeli, but he knew that pensions, unlike the minimum wage, would affect soldiers. Stavros, a smart man in his own right, knew that a minimum wage would just mean fewer workers got hired. Therefore, he supported the pension plan, and brought in the Mexican War veteran, in exchange for a 5% increase for the rich tax rate. This would undercut Disraeli and Bismarck. In the end, Stavros proved the smartest of the three and got what he wanted.

Nikolai voted for the bill with all the other Militares, but he felt a bad taste in his mouth as he did. He couldn't help but think that, in all of these political intricacies, the welfare of the Empire was being ignored.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

12 January 1875, Munich, Bavaria

Magnus von Horgen, the exiled ex-Minister of Security, cackled with glee. That old fool Bismarck did exactly what I thought he would; he's declared war on Bavaria!

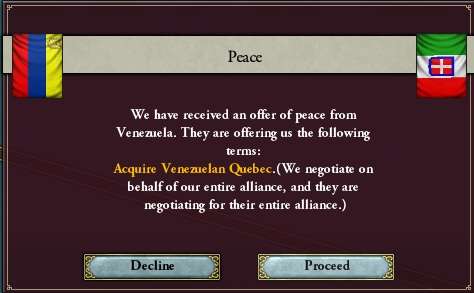

Horgen, as the leader of the Roman Whites, had been planning an uprising for some time, ever since the Empire had gone to war with Venezuela at the urging of the United States.

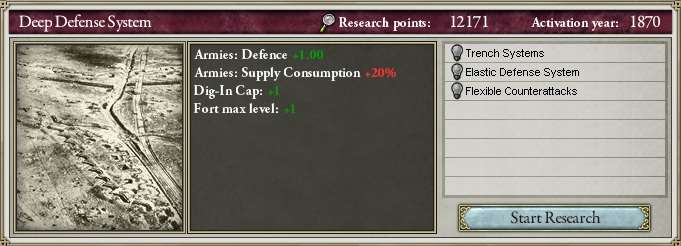

Arturo Orsatti had crippled most of Horgen's network within the Ministry of Security, and unlike the Jacobins, he didn't have the kind of resources or connections to work at a local level. He had eager followers and a thorough knowledge of Roman defenses, but that was it. Even worse, his spies in the Ministry of Education had told him that the army was redesigning all fortifications in a "deep defense system" to help local garrisons hold out against rebellions.

That meant he had to strike and strike soon. He still harbored some hopes of restoring the formerly awe-inspiring power and authority of the Roman Empire, if he could only find a suitable Emperor and, of course, dispose of the previous one. Maybe if I get rid of Constantine, Trajan, and Ferdinand, Gabriele will be more pliable? Magnus shook his head to clear it of such peremptory thoughts. First, he had to seize control of Rome. That meant initiating the revolution.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

22 April 1875, office of the Chief of the General Staff, Florence

Helmuth von Moltke grunted as he reviewed the Bavarian situation. General di Savoia, the nominal Chief of the General Staff, had gone to Rome to consult with the Emperor, leaving his capable General to deal with two rebellions and a war.

Situation on 13 January

Initially, the Bavarian regular army had held only one province: Nuremburg. A victory in Stuttgart easily defeated that, but mere days later, the Bavarian militia struck its own blow. If not for Roman machine guns, they might even have prevailed, outnumbering the legions 2 to 1.

The Battle of Munich -- and General Pallavicino -- was a scare for the legions. Much more terrifying was a second rising, this time by the Jacobins, who were dangerously close to Rome.

At first, Minister Orsatti suspected some sort of coordination between Horgen and the mysterious leader of the Jacobins, but that seemed very unlikely. That was why he'd come to the General Staff building after securing Naples. Orsatti sat across from Moltke as they considered possible suspects. Orsatti and Moltke were, in one fashion, of a kind -- both had risen through the ranks of the army, both had incurred political troubles for circumstances out of their control, and both were extremely serious about defending the Empire. Orsatti was particularly interested in getting rid of Horgen, as the reactionary movement centered very clearly around him. Moltke was most concerned about defeating Bavaria quickly; he had no fears regarding of the competence of the legions to deal with untrained zealots or insane terrorists.

Moltke ruminated about their victories in sieges as Orsatti reviewed the battle reports. The fall of Augsburg and Munich had triggered the first Bavarian offer of white peace, something Moltke would never have accepted. In fact, when reading the offer, he clearly recognized Bismarck's handwriting, a single emphatic "Hah!" in the margins.

As Orsatti flipped through the prisoner lists, he spotted an unusual name. "Helmuth?"

Moltke looked up from his papers. "Yes, Arturo?"

"My German is a little rusty. Is 'Todd' a common name?"

"No, not at all. Not in German. I believe it is normally English or Scottish."

Arturo started to show excitement. "But Kaiser, that is good German?"

Moltke nodded slowly. "It is our equivalent of Imperator. Why do you ask these questions? Do you have nothing better to do than get lessons?"

"I have a Todd von Kaiser on this list."

Now Moltke's face started to flush. "Do you know what Tod von Kaiser might mean?"

Orsatti smiled. "Death of the Emperor?"

"Precisely."

"I think my men should have a chat with Herr von Kaiser, don't you agree?"

Moltke nodded again. Orsatti left, determined to interrogate the prisoner himself. The German General was left alone to study the Battle of Nuremberg.

Our victory is all but certain. Ingolstadt has a month, maybe less. The Bavarian army is broken. Orsatti will put an end to the reactionaries, once and for all. This Empire may survive after all, survive and thrive.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

24 December 1875, Imperial Palace, Rome

Normally, Christmas Eve was not a public affair for the Farneses, even as the Imperial family, but in 1875, it was both Christmas Eve and a state wedding. Prince Ferdinand, unusually for the Imperial family, had married a commoner. His new bride was a lovely lass from Bologna named Olivia Donatelli. For the first time in a long time, the entire Cabinet attended a formal function. There was a lot to celebrate, including the ends to Rome's two wars and a Russian war over the annexation of Slovakia.

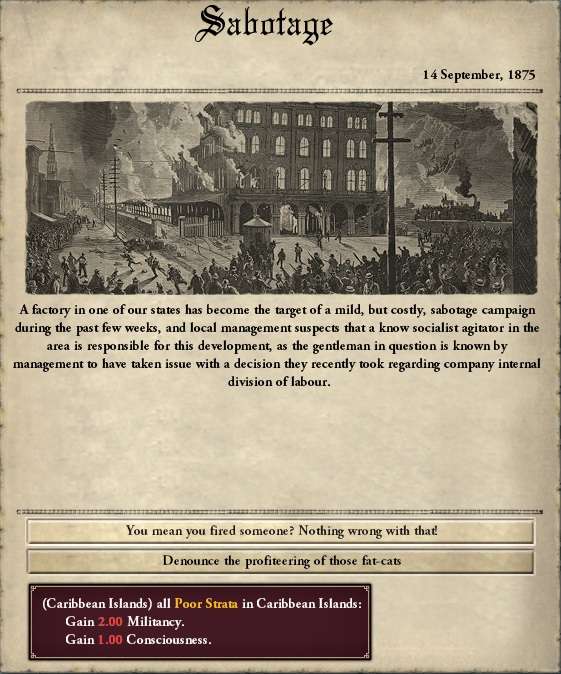

The one discordant note was a bomb in a factory in Jamaica; the perpetrators were quickly apprehended, but their appeal for leniency was quickly denied: they were executed at the Governor of Jamaica's order.

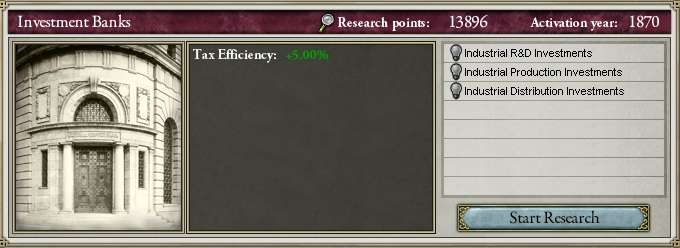

Even that didn't dampen the evening too much; while the party continued, some Senators hashed out the details of an Imperial finance plan for some prominent banks; these new banks, specializing in private capital, would help stimulate the Roman economy.

Arturo Orsatti checked his pocket watch as Caroline Sheridan used the restroom. He tapped his foot impatiently; the Emperor was going to confer a special promotion on Arturo for the arrest of Magnus von Horgen, aka Todd von Kaiser. His army rank would be Commander; although this didn't matter much in terms of his political power, as Arturo was still retired from the army, he still received the patent of hereditary nobility the rank conferred, and an increase in his pension too. Both were welcome, especially as Caroline and he were engaged as of a few weeks ago. Caroline finally came out, looked sheepishly at her fiancee, and both made their way towards the main ball room. Constantine XII smiled as he saw Orsatti and Sheridan enter the room.

"There we are, ladies and gentlemen! I remember when Trajan and I were little boys and we first heard about Arturo in the army. It's nice to be able to do something for a family friend. Come on, Laura, come and meet the hero!"

At that exact moment, three things happened.

Laura Datti, Empress of Rome, put on her glasses to spot the couple.

Arturo Orsatti's eyes widened in recognition; he thought he'd never met the Empress, but he was gravely mistaken.

Constantine XII looked in confusion as Arturo motioned for the guards and pointed at his wife.

Then, in one awful instant, the entire Empire changed. Arturo screamed at the top of his lungs, "That's her! That's the woman from the library! She's a Jacobin!" Laura Datti, her cover blown, extracted a dagger from her bodice, cut her husband's throat, and tried to jump out the window before getting shot by an alert guard right in the leg. Guards surrounded her, while Orsatti and his agents from the Ministry of Security spirited away the remaining members of the Imperial family. Constantine XII, on the other hand, crumpled to the floor, blood spurting from his neck. Laura knew her business, and made sure that her blow was a killing one. He was dead within moments.

Who was Emperor? Why had Laura Datti, devoted wife, mother, and Empress done this? Were the Jacobins finally done for once and for all?

For the answers to these -- and other questions -- look for the next update!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I was trying to find a good place to stop for a while; I know I've left you all on a tremendous cliffhanger, but the thing is, I'm leaving on Sunday and I'll be out of town until the end of June, away from my PC. I'll still monitor the thread, but I won't be able to update until the first week of July. I hope I've given you plenty to talk about!

*Leaves massive, epic cliffhanger*

"Okay all, I'll be gone for the rest of the month. Peace!"

So cruel Avi...

"Okay all, I'll be gone for the rest of the month. Peace!"

So cruel Avi...

*Leaves massive, epic cliffhanger*

"Okay all, I'll be gone for the rest of the month. Peace!"

So cruel Avi...

I have to make you'll all still be here when I get back.