Good to see this return, very good updates too. Rather worrying that war seems imminent with Mexico but seemingly the army is in good shape, the USCA has a new ally and apparently it will soon even have a fleet. Hopefully she will thus be able to give Santa Anna a bloody nose.

Libre, Soberana y Independiente - The Storied History of the Central American Navy

- Thread starter MastahCheef117

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Part IX - The Department of the Navy

When Bernardo Barillas was at the port - as he was every day - sitting, watching the ships dock and undock and load and unload their cargo - he was unsurprised and amused when he heard the newspaper boys yelling today: "¡Departamento de la Marina de Guerra establecido!" His ploy had worked. Sipping from his tea, sitting at a table outside of a local restaurant, he felt an onrushing wave of self-pride: he had, though not directly, established a Central American Navy.

He paid for his food, and as he was about to leave, he was met by a young man dressed in military uniform; however, it was a uniform he had not yet seen before. "You are Señor Barillas?" he asked. "Yes," Bernardo replied, somewhat stunned, "that would be me." The man nodded and smiled. "Then please, señor, follow me."

As he led him onto the street, he scrutinized the man's uniform more closely: on his shoulders were golden epaulettes, his uniform a darker blue than most others; a badge on his chest signified a rank Bernardo had not yet seen before. Soon they came to a carriage, headed by two horses, one brown and one black. The man opened the door, and allowed Bernardo to step foot inside. The man followed, closed the door, and signaled the driver off.

As the carriage continued on its way, Bernardo noticed the decreased density in which he saw people and houses on the side of the road. They were on the outskirts of town when they came to a stop. As they exited, Bernardo followed the man down a pathway to the porch of a house. They entered, and what happened next astounded Bernardo.

At the end of the room was a desk piled with dozens of papers. A man behind it sat, entranced with the work he was in. He wore the same uniform as the man that had lead Bernardo to this place: the badge on his chest, however, was different.

"Lieutenant, I have found the man we are looking for," said the uniformed guide. He stood at attention on one side of the desk, looking ahead. The man at the desk looked up, stood, and smiled. "And you must be Señor Barillas, no? I am Lieutenant Rios; welcome to the Department of the Navy."

Bernardo was astounded. He observed the room fully: behind Lieutenant Rios was a door, beyond which he could see several more desks, each one topped with dozens of papers with men working furiously. There was a telegraph in the corner, upon which a man was sending a message; men stood around, conversing and speaking with one another and the men at the desks. They all wore the same uniforms: a dark blue, some with epaulettes, some without, all a part of the Department of the Navy.

The first home of the Department of the Navy in 1838 - a photograph taken

by the previous owners of the house (date unknown, suspected around 1833)

The uniformed guide was then excused, and walked into the depths of the office. "So, Lieutenant, why have I been brought here?" Bernardo asked, his curiosity overtaking him. Rios, approaching the door to the busy room behind him, replied, "We have much to talk about, Señor Barillas."

Unsatisfied with too ominous an answer, Barillas silenced himself and followed Rios through the door. They crossed through the busy room - officially the fully-employed Department of the Navy - and came to another door. Painted, in thick, black letters, read the words "Sec., Department of the Navy"

The door opened, and Barillas, expecting to see a yet another blue-clad man sitting behind the desk that filled up most of the room, was mistaken. Instead, a man of medium height in a black overcoat and dark brown pants was in place. His hair was longer than the hair of most other men in the building, falling just short of his shoulders. His skin was abnormally light for a man living in the Republic; he was most likely an immigrant, of the son of immigrants from a place farther north of Spain in Europe.

Rios closed the door behind Barillas, leaving him alone with the Secretary. There was a silence as the two looked at each other: Barillas staring into the man's bright blue eyes, and the man staring right back. Then, he clapped his hands, rubbing them together, and smiled. "Hola, Señor Barillas. Please, have a seat."

Barillas, having been introduced to too many people in the past two minutes, was uneasy. He took a seat in the small wooden chair opposite of the Secretary's large comforted seat. "I, as you may have read on the door, am Secretary of the Navy Antonio Moreno. I have been put in command of the Department by President Morazán and Secretary of War Jaimes Torres. Naturally, you may already know that a large reason why I am employed in such a position, and why you are even here, is because you visited a certain Army recruiting station several days ago. It took one slip of paper to convince Morazán to spend quite a lot of pesos - about one hundred-fifty thousand, to be exact - to set us up a nice little home that the Ortega family kindly sold to us for a meager sum." At this, he picked up a tiny piece of paper from his desk and waved it in the air tiredly, raising his eyebrows in amusement.

"And now, we get to where I tell you the important news." Moreno stood and walked over to Barillas's seat. "We can't have a navy that is occupied with a bunch of pencil-pushing lieutenants sitting at a desk and a Secretary," he said, snorting, "we need leaders. We need men who can lead our ships - or lack thereof, at this moment - to battle, if fate ever called for it."

Barillas looked up at Moreno. "So, I'm guessing I'm to look for one who can lead our ships when they exist?"

Moreno's eyes, wide with anticipation, bore down on Barillas. "No, Señor. You are that new leader."

Barillas looked at him, doubtful, furrowing his brow. "What are you saying exactly, Secretary?"

Moreno walked back to his desk, sitting down and grabbing a pencil. "You are the first Captain of the Centroamericano de la Armada - the Central American Navy." He leaned over his desk and began writing. "You are excused, Captain. I expect to see you here at eight-o'clock tomorrow morning. We have much to do."

Barillas, having been employed, promoted and honored in a time span of less than ten seconds, was speechless. "Thank you, Secretary," he spoke awkwardly, and left.

****

When Bernardo Barillas was at the port - as he was every day - sitting, watching the ships dock and undock and load and unload their cargo - he was unsurprised and amused when he heard the newspaper boys yelling today: "¡Departamento de la Marina de Guerra establecido!" His ploy had worked. Sipping from his tea, sitting at a table outside of a local restaurant, he felt an onrushing wave of self-pride: he had, though not directly, established a Central American Navy.

He paid for his food, and as he was about to leave, he was met by a young man dressed in military uniform; however, it was a uniform he had not yet seen before. "You are Señor Barillas?" he asked. "Yes," Bernardo replied, somewhat stunned, "that would be me." The man nodded and smiled. "Then please, señor, follow me."

As he led him onto the street, he scrutinized the man's uniform more closely: on his shoulders were golden epaulettes, his uniform a darker blue than most others; a badge on his chest signified a rank Bernardo had not yet seen before. Soon they came to a carriage, headed by two horses, one brown and one black. The man opened the door, and allowed Bernardo to step foot inside. The man followed, closed the door, and signaled the driver off.

As the carriage continued on its way, Bernardo noticed the decreased density in which he saw people and houses on the side of the road. They were on the outskirts of town when they came to a stop. As they exited, Bernardo followed the man down a pathway to the porch of a house. They entered, and what happened next astounded Bernardo.

At the end of the room was a desk piled with dozens of papers. A man behind it sat, entranced with the work he was in. He wore the same uniform as the man that had lead Bernardo to this place: the badge on his chest, however, was different.

"Lieutenant, I have found the man we are looking for," said the uniformed guide. He stood at attention on one side of the desk, looking ahead. The man at the desk looked up, stood, and smiled. "And you must be Señor Barillas, no? I am Lieutenant Rios; welcome to the Department of the Navy."

Bernardo was astounded. He observed the room fully: behind Lieutenant Rios was a door, beyond which he could see several more desks, each one topped with dozens of papers with men working furiously. There was a telegraph in the corner, upon which a man was sending a message; men stood around, conversing and speaking with one another and the men at the desks. They all wore the same uniforms: a dark blue, some with epaulettes, some without, all a part of the Department of the Navy.

The first home of the Department of the Navy in 1838 - a photograph taken

by the previous owners of the house (date unknown, suspected around 1833)

The uniformed guide was then excused, and walked into the depths of the office. "So, Lieutenant, why have I been brought here?" Bernardo asked, his curiosity overtaking him. Rios, approaching the door to the busy room behind him, replied, "We have much to talk about, Señor Barillas."

Unsatisfied with too ominous an answer, Barillas silenced himself and followed Rios through the door. They crossed through the busy room - officially the fully-employed Department of the Navy - and came to another door. Painted, in thick, black letters, read the words "Sec., Department of the Navy"

The door opened, and Barillas, expecting to see a yet another blue-clad man sitting behind the desk that filled up most of the room, was mistaken. Instead, a man of medium height in a black overcoat and dark brown pants was in place. His hair was longer than the hair of most other men in the building, falling just short of his shoulders. His skin was abnormally light for a man living in the Republic; he was most likely an immigrant, of the son of immigrants from a place farther north of Spain in Europe.

Rios closed the door behind Barillas, leaving him alone with the Secretary. There was a silence as the two looked at each other: Barillas staring into the man's bright blue eyes, and the man staring right back. Then, he clapped his hands, rubbing them together, and smiled. "Hola, Señor Barillas. Please, have a seat."

Barillas, having been introduced to too many people in the past two minutes, was uneasy. He took a seat in the small wooden chair opposite of the Secretary's large comforted seat. "I, as you may have read on the door, am Secretary of the Navy Antonio Moreno. I have been put in command of the Department by President Morazán and Secretary of War Jaimes Torres. Naturally, you may already know that a large reason why I am employed in such a position, and why you are even here, is because you visited a certain Army recruiting station several days ago. It took one slip of paper to convince Morazán to spend quite a lot of pesos - about one hundred-fifty thousand, to be exact - to set us up a nice little home that the Ortega family kindly sold to us for a meager sum." At this, he picked up a tiny piece of paper from his desk and waved it in the air tiredly, raising his eyebrows in amusement.

"And now, we get to where I tell you the important news." Moreno stood and walked over to Barillas's seat. "We can't have a navy that is occupied with a bunch of pencil-pushing lieutenants sitting at a desk and a Secretary," he said, snorting, "we need leaders. We need men who can lead our ships - or lack thereof, at this moment - to battle, if fate ever called for it."

Barillas looked up at Moreno. "So, I'm guessing I'm to look for one who can lead our ships when they exist?"

Moreno's eyes, wide with anticipation, bore down on Barillas. "No, Señor. You are that new leader."

Barillas looked at him, doubtful, furrowing his brow. "What are you saying exactly, Secretary?"

Moreno walked back to his desk, sitting down and grabbing a pencil. "You are the first Captain of the Centroamericano de la Armada - the Central American Navy." He leaned over his desk and began writing. "You are excused, Captain. I expect to see you here at eight-o'clock tomorrow morning. We have much to do."

Barillas, having been employed, promoted and honored in a time span of less than ten seconds, was speechless. "Thank you, Secretary," he spoke awkwardly, and left.

****

@ morningSIDEr: We shall see

just caught up again, great set of updates and an interesting strategy. Wouldn't Colombia have been a better ally than Venezueala (which when AI run is much the weaker of the two) and Barillas is going to have a big job to generate a decent navy for you ... but then the title of the AAR leaves you little choice but to try to build one ... after all

Part X - The Six Frigates

For many Latin American countries, the United States had been a model of democracy, liberty, freedom, and effective, non-tyrannical government. The American Revolution, conducted against the world's greatest military power, had been successful. The people of America - not just of the United States, but of Mexico, of Central America, of Brazil, and Argentina, and Chile - could achieve anything.

This was how Central America would view itself for many years following its independence.

In the 1790s, proposals had been laid down in the United States for the building, construction, and deployment of six frigates to be commissioned into the United States Navy. These ships - to become the USS Constellation, Constitution, United States, Chesapeake, Congress, and President - would be finished and manned over a period of several years. In the Quasi War of 1798 to 1800, USS Constellation, under the command of Captain Thomas Truxtun, secured many victories against French privateers, the most known of which was fought against the 40-gun frigate L'Insurgente. The small conflicts in the Quasi War - in which only two of the six frigates, Constellation and the newly-commissioned Constitution had participated - had given the few commanders and seamen of the United States Navy valuable experience in combat, as well as lessons learned in the expansion of the world's newest formidable navy.

USS Constellation at sea. Her 38-gun armament was smaller than

the 44 guns of Constitution, President, and United States

It is widely believed among historians that President Morazán, Jaime Torres, Antonio Moreno, and Bernardo Barillas were widely inspired by the stories and lore of the first days of the United States Navy.

The first day of work was brutal for Bernardo Barillas, new Captain of the Central American Navy. He was bombarded by budget reports and political rhetoric, which he demanded be directed towards his secretary, a Corporal Hidalgo. Over time he had adjusted to his new life, a life he readily accepted if it would further the country he had been born into and lived in for quite some time, a country he loved dearly. He was perpetually found in the office of Secretary Moreno, where he was often met by Secretary Torres and were supplied with a box of cigars, a pile of budgetary papers and entire reports by Secretary Vega [of the Treasury]. They would talk for hours on end, of how to continue sufficient funding for the Navy, how to organize and establish a hierarchy within the Department, and how to begin going about building the Republic a navy from the ground up. As time went on, the conversations dwindled into small talk and, soon, nothing - the two of them, occasionally accompanied by Secretary Torres - as they sat did nothing, wordlessly writing out reports and requests and letters to be sent to the Department or other Departments or other sections of the government, dreaming in their heads a way to spark conversation, or doing absolutely nothing at all, enjoying the tobacco that Secretary Moreno had so generously supplied them with.

One day, however - it would be August 11, Captain Barillas would later recall - that when they entered Moreno's office for their daily conference, they found but a single letter on the oaken wood desk, sent from a Alexander Mueller, an immigrant from northern Germany. He claimed to be a shipwright and owner of a shipping company based in San Salvador. He had - though illegally, he admitted - built war-grade ships that would be able to withstand punishment from any privateers or pirates attempting to plunder them. He claimed he had experience with designing ships that could take punishment equivalent of a heavy frigate, and dish out just as much with a heavy, concentrated battery of guns. He was immediately invited to a conference with Barillas and Moreno.

****

"Ah, Captain Barillas! And Secretary Moreno; it is an honor to meet such men as yourselves."

Mueller had entered the room with nothing less than a grand entrance, strutting into a conversation involving cigars and papers while dressed for the occasion: he had a large-brimmed hat with a gleaming white feather plucked into its side, high, black boots, well-fitting pants and a clean, pressed vest over his shirt.

Barillas and Moreno shook hands and continued with the pleasantries. As Moreno sat, relaxed, in his usual chair, and Barillas swung a bare wooden seat from the corner, Mueller sat in the guest chair opposite Moreno. "Now, I hear the two of you have quite the obstacle?"

Moreno nodded, still smoking his cigar. Leaning back in his chair, he pointed at Mueller, cigar still between his fingers. "And it has been said that you have what it takes to get us past this obstacle?" he said amused, a wisp of smoke wafting into the air with the smell of pure tobacco.

Mueller smiled. "Then those that have said so could be quite right," he said enticingly. "Though my actions may be deemed illegal, I promise that they have only been done with the supreme intentions for the Central American state," he continued, nodding assuredly. "I have armed very trustworthy merchants with only the highest-quality ships that could fight like a man o' war if they had to. Protect against privateers, pirates, and the like. I've equipped a few of my own ships similarly as well."

This brought about a chuckle from Moreno. "And why is it then, Señor Mueller, that you have not come to us earlier? We established the Department months ago and have been notifying everyone from New Orleans to Santiago of our cause to establish a navy for the safety of the South American coast and the Caribbean?"

Mueller was struck, but quickly recovered. "Didn't want to react too quickly. God knows it could've been a ploy to catch people like me. Non-government men trying to do the right thing and strike back at the pirates. Naturally, I would've been viewed as immoral." Mueller then smirked, holding back his own chuckle. "Bad for business, you know."

There was a silence as the two Navy men observed Mueller, and Mueller observed back. Then Barillas, standing, said, "Señor Mueller, we have a proposition. If you wish to cooperate in our building and constructing of a navy, we will have the Court of the Republic drop any charges that may be made by the confessions you made to get yourself in this room today." Mueller observed the words, nodding and scratching his chin. He then nodded, assuring himself moreso than the two men he was conversing with, and smiled yet again. "Yes, I can agree to this. I will do anything for the Republic, as I have already done. I would do anything more for Central American than for Prussia. No respect for the ship, Prussia has. They believe that the Army is the central piece for any military. How wrong they are. I just hope they don't claim leadership over Germany one day."

Moreno and Barillas, eyeing one another and keeping themselves from laughing, nodded and m-hm'd to keep Mueller's attention. The meeting, however short and informal it had been, was a success.

A photograph of businessman

Alexander Mueller, dated 1857

****

Mueller would begin serving the government of Central America by bringing to Moreno's office several days later his blueprints for several ships that he had employed by his company. One type caught the eye of the two seamen immediately - a heavy frigate, fast enough to battle sloops and heavy heavy and powerful enough to out-battle a ship-of-the-line. The ships would be armed with a 46-gun main armament and would weigh in at over 2,300 tons.

Moreno and Barillas both wrote a letter to President Morazán stating the outcome of the meeting on August 11 and the plans they had already drawn up. Six frigates would be built - three frigates in the Caribbean, and three frigates in the Pacific. Two frigates would be built at Guatemala City, and one at San Salvador, both on the west coast. On the east coast, a much less densely-populated region, one frigate would be built at San Pedro Sula, one at Puerto Barrios, and one at Puerto Lempira.

The two frigates to be built at Guatemala City would be named Suerte - Luck - and Leopardo - Leopard. The frigate built at San Salvador would be christened as the Halcón - Falcon.

The frigate built in Puerto Barrios was to be named Unidad, Unity; the frigate in San Pedro Sula, Tiburón, Shark; and the frigate in Puerto Lempira, Primer Ministro, the Prime Minister.

Indeed, Central America was to have it's Six Frigates.

For many Latin American countries, the United States had been a model of democracy, liberty, freedom, and effective, non-tyrannical government. The American Revolution, conducted against the world's greatest military power, had been successful. The people of America - not just of the United States, but of Mexico, of Central America, of Brazil, and Argentina, and Chile - could achieve anything.

This was how Central America would view itself for many years following its independence.

In the 1790s, proposals had been laid down in the United States for the building, construction, and deployment of six frigates to be commissioned into the United States Navy. These ships - to become the USS Constellation, Constitution, United States, Chesapeake, Congress, and President - would be finished and manned over a period of several years. In the Quasi War of 1798 to 1800, USS Constellation, under the command of Captain Thomas Truxtun, secured many victories against French privateers, the most known of which was fought against the 40-gun frigate L'Insurgente. The small conflicts in the Quasi War - in which only two of the six frigates, Constellation and the newly-commissioned Constitution had participated - had given the few commanders and seamen of the United States Navy valuable experience in combat, as well as lessons learned in the expansion of the world's newest formidable navy.

USS Constellation at sea. Her 38-gun armament was smaller than

the 44 guns of Constitution, President, and United States

It is widely believed among historians that President Morazán, Jaime Torres, Antonio Moreno, and Bernardo Barillas were widely inspired by the stories and lore of the first days of the United States Navy.

The first day of work was brutal for Bernardo Barillas, new Captain of the Central American Navy. He was bombarded by budget reports and political rhetoric, which he demanded be directed towards his secretary, a Corporal Hidalgo. Over time he had adjusted to his new life, a life he readily accepted if it would further the country he had been born into and lived in for quite some time, a country he loved dearly. He was perpetually found in the office of Secretary Moreno, where he was often met by Secretary Torres and were supplied with a box of cigars, a pile of budgetary papers and entire reports by Secretary Vega [of the Treasury]. They would talk for hours on end, of how to continue sufficient funding for the Navy, how to organize and establish a hierarchy within the Department, and how to begin going about building the Republic a navy from the ground up. As time went on, the conversations dwindled into small talk and, soon, nothing - the two of them, occasionally accompanied by Secretary Torres - as they sat did nothing, wordlessly writing out reports and requests and letters to be sent to the Department or other Departments or other sections of the government, dreaming in their heads a way to spark conversation, or doing absolutely nothing at all, enjoying the tobacco that Secretary Moreno had so generously supplied them with.

One day, however - it would be August 11, Captain Barillas would later recall - that when they entered Moreno's office for their daily conference, they found but a single letter on the oaken wood desk, sent from a Alexander Mueller, an immigrant from northern Germany. He claimed to be a shipwright and owner of a shipping company based in San Salvador. He had - though illegally, he admitted - built war-grade ships that would be able to withstand punishment from any privateers or pirates attempting to plunder them. He claimed he had experience with designing ships that could take punishment equivalent of a heavy frigate, and dish out just as much with a heavy, concentrated battery of guns. He was immediately invited to a conference with Barillas and Moreno.

****

"Ah, Captain Barillas! And Secretary Moreno; it is an honor to meet such men as yourselves."

Mueller had entered the room with nothing less than a grand entrance, strutting into a conversation involving cigars and papers while dressed for the occasion: he had a large-brimmed hat with a gleaming white feather plucked into its side, high, black boots, well-fitting pants and a clean, pressed vest over his shirt.

Barillas and Moreno shook hands and continued with the pleasantries. As Moreno sat, relaxed, in his usual chair, and Barillas swung a bare wooden seat from the corner, Mueller sat in the guest chair opposite Moreno. "Now, I hear the two of you have quite the obstacle?"

Moreno nodded, still smoking his cigar. Leaning back in his chair, he pointed at Mueller, cigar still between his fingers. "And it has been said that you have what it takes to get us past this obstacle?" he said amused, a wisp of smoke wafting into the air with the smell of pure tobacco.

Mueller smiled. "Then those that have said so could be quite right," he said enticingly. "Though my actions may be deemed illegal, I promise that they have only been done with the supreme intentions for the Central American state," he continued, nodding assuredly. "I have armed very trustworthy merchants with only the highest-quality ships that could fight like a man o' war if they had to. Protect against privateers, pirates, and the like. I've equipped a few of my own ships similarly as well."

This brought about a chuckle from Moreno. "And why is it then, Señor Mueller, that you have not come to us earlier? We established the Department months ago and have been notifying everyone from New Orleans to Santiago of our cause to establish a navy for the safety of the South American coast and the Caribbean?"

Mueller was struck, but quickly recovered. "Didn't want to react too quickly. God knows it could've been a ploy to catch people like me. Non-government men trying to do the right thing and strike back at the pirates. Naturally, I would've been viewed as immoral." Mueller then smirked, holding back his own chuckle. "Bad for business, you know."

There was a silence as the two Navy men observed Mueller, and Mueller observed back. Then Barillas, standing, said, "Señor Mueller, we have a proposition. If you wish to cooperate in our building and constructing of a navy, we will have the Court of the Republic drop any charges that may be made by the confessions you made to get yourself in this room today." Mueller observed the words, nodding and scratching his chin. He then nodded, assuring himself moreso than the two men he was conversing with, and smiled yet again. "Yes, I can agree to this. I will do anything for the Republic, as I have already done. I would do anything more for Central American than for Prussia. No respect for the ship, Prussia has. They believe that the Army is the central piece for any military. How wrong they are. I just hope they don't claim leadership over Germany one day."

Moreno and Barillas, eyeing one another and keeping themselves from laughing, nodded and m-hm'd to keep Mueller's attention. The meeting, however short and informal it had been, was a success.

A photograph of businessman

Alexander Mueller, dated 1857

****

Mueller would begin serving the government of Central America by bringing to Moreno's office several days later his blueprints for several ships that he had employed by his company. One type caught the eye of the two seamen immediately - a heavy frigate, fast enough to battle sloops and heavy heavy and powerful enough to out-battle a ship-of-the-line. The ships would be armed with a 46-gun main armament and would weigh in at over 2,300 tons.

Moreno and Barillas both wrote a letter to President Morazán stating the outcome of the meeting on August 11 and the plans they had already drawn up. Six frigates would be built - three frigates in the Caribbean, and three frigates in the Pacific. Two frigates would be built at Guatemala City, and one at San Salvador, both on the west coast. On the east coast, a much less densely-populated region, one frigate would be built at San Pedro Sula, one at Puerto Barrios, and one at Puerto Lempira.

The two frigates to be built at Guatemala City would be named Suerte - Luck - and Leopardo - Leopard. The frigate built at San Salvador would be christened as the Halcón - Falcon.

The frigate built in Puerto Barrios was to be named Unidad, Unity; the frigate in San Pedro Sula, Tiburón, Shark; and the frigate in Puerto Lempira, Primer Ministro, the Prime Minister.

Indeed, Central America was to have it's Six Frigates.

Last edited:

A rather motley crew has thus been assembled and the first of the USCA's ships are under construction. I'm rather looking forward to reading about their first use in war.

Part XI - Impediments

The plans for the construction of the first six frigates of the Navy were set in stone for quite a while; it was the resources and funds, or lack thereof, that continually slowed and delayed their production. Construction on the first of the frigates, Suerte, had already halted before the keel was even laid. The government treasury, though must larger than it was two years before, was still too small to support the construction of all six frigates at the same time. The population of several of the cities were too small to keep powerful 46-gun frigates at the peak of construction speed. Numbers of cannon, ammunition and powder for said cannon, as well as masts, rigging, and the sheer amount of lumber needed for the construction of the six ships was too great. The cost of a single frigate amounted to nearly 1,000,000 Central American pesos (as of August 1838), almost one-fourth of the nation's total GDP, a paltry number within itself. Many within Congress became skeptical of the huge costs it would take to not only build these frigates, but to man and maintain them over long periods and distances. Members of both the Liberals and Conservatives began to break away and came into conflict with the pro-naval expansionists.

Among these breakaway politicians was Esteban Vega, Secretary of the Treasury and opponent to any further military expansion. Vega's position on the ordeal was not surprising; he had already vehemently opposed the already in-effect military alliance with Venezuela to the south, a quarrel that had gone relatively unnoticed on his part. Vega was enraged that President Morazán was about to, as he worded it, "ignore his points yet again" in the expansion of the navy that was to drain the treasury of a huge percentage of the country's budget. Vega had behind him a sizeable amount of Senators, and though not a majority, they would prove a difficult barrier to those pushing for the proper funding for the fledgling navy.

Esteban Vega, disgruntled Secretary of the Treasury who

felt betrayed by President Morazán and his Liberal allies

The Reactionary minority pushed violently for the funding for the navy to be allocated as quickly as possible. The Conservatives, though not as equally unified or determined, also supported the expansion. It was the Liberal party, generally one to preach general stability and unity, was the party that was torn between Morazán and his now-split cabinet and Vega's cause. Morazán argued that, despite the high cost of one frigate, the coffers would quickly be refilled and a commitment could be made to begin construction on another frigate. Vega, a master at economics, argued against this that the sudden, massive decrease in the GDP of the nation could bring about a recession that could, if handled crudely enough, destabilize the economy for an extended period of time: the frigates were simply not worth the risk, he said.

Bickering within the Congress and the President's own cabinet intensified as the month went past. It was not until September 5 that Vega relented, having lost the support of a number of Senators as well as making several blunders in his arguments that were attended by thousands. He quickly reshuffled his views on the subject and supported, albeit reluctantly and somewhat quietly, supplying the navy with the funds required to build the frigates.

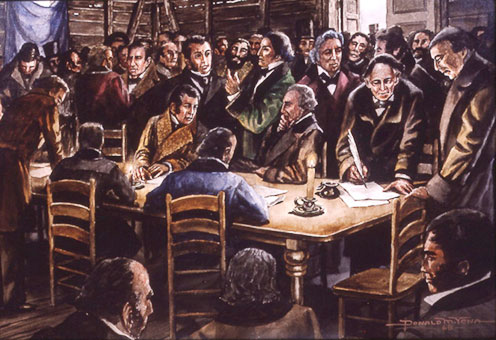

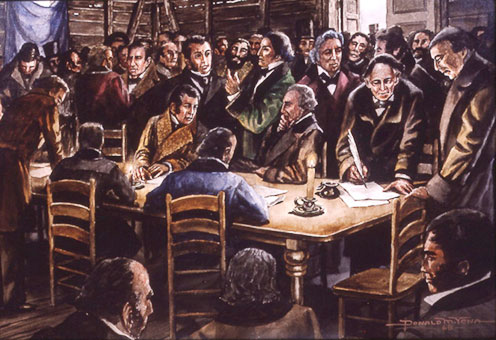

President Morazán (at right, signing parchment) authorizing the

funding for the construction of the six frigates, September 6, 1838

On September 23, with Alexander Mueller presiding over the occasion, the first frigate of the Central America Navy, Suerte, was laid down in Guatemala Harbor. It was to be but the first of many.

****

The plans for the construction of the first six frigates of the Navy were set in stone for quite a while; it was the resources and funds, or lack thereof, that continually slowed and delayed their production. Construction on the first of the frigates, Suerte, had already halted before the keel was even laid. The government treasury, though must larger than it was two years before, was still too small to support the construction of all six frigates at the same time. The population of several of the cities were too small to keep powerful 46-gun frigates at the peak of construction speed. Numbers of cannon, ammunition and powder for said cannon, as well as masts, rigging, and the sheer amount of lumber needed for the construction of the six ships was too great. The cost of a single frigate amounted to nearly 1,000,000 Central American pesos (as of August 1838), almost one-fourth of the nation's total GDP, a paltry number within itself. Many within Congress became skeptical of the huge costs it would take to not only build these frigates, but to man and maintain them over long periods and distances. Members of both the Liberals and Conservatives began to break away and came into conflict with the pro-naval expansionists.

Among these breakaway politicians was Esteban Vega, Secretary of the Treasury and opponent to any further military expansion. Vega's position on the ordeal was not surprising; he had already vehemently opposed the already in-effect military alliance with Venezuela to the south, a quarrel that had gone relatively unnoticed on his part. Vega was enraged that President Morazán was about to, as he worded it, "ignore his points yet again" in the expansion of the navy that was to drain the treasury of a huge percentage of the country's budget. Vega had behind him a sizeable amount of Senators, and though not a majority, they would prove a difficult barrier to those pushing for the proper funding for the fledgling navy.

Esteban Vega, disgruntled Secretary of the Treasury who

felt betrayed by President Morazán and his Liberal allies

The Reactionary minority pushed violently for the funding for the navy to be allocated as quickly as possible. The Conservatives, though not as equally unified or determined, also supported the expansion. It was the Liberal party, generally one to preach general stability and unity, was the party that was torn between Morazán and his now-split cabinet and Vega's cause. Morazán argued that, despite the high cost of one frigate, the coffers would quickly be refilled and a commitment could be made to begin construction on another frigate. Vega, a master at economics, argued against this that the sudden, massive decrease in the GDP of the nation could bring about a recession that could, if handled crudely enough, destabilize the economy for an extended period of time: the frigates were simply not worth the risk, he said.

Bickering within the Congress and the President's own cabinet intensified as the month went past. It was not until September 5 that Vega relented, having lost the support of a number of Senators as well as making several blunders in his arguments that were attended by thousands. He quickly reshuffled his views on the subject and supported, albeit reluctantly and somewhat quietly, supplying the navy with the funds required to build the frigates.

President Morazán (at right, signing parchment) authorizing the

funding for the construction of the six frigates, September 6, 1838

On September 23, with Alexander Mueller presiding over the occasion, the first frigate of the Central America Navy, Suerte, was laid down in Guatemala Harbor. It was to be but the first of many.

****

@ loki100: Mueller, although not ingame, will play a much larger part later on as well

@ morningSIDEr: We shall see

Last edited:

nice view on the political scheming behind the decision ... but presume this is not the end of the debate?

It did seem the idea of a USCA navy would sink long before the frigates themselves were built but thankfully there is enough support. For now anyway.