Derahan- Thanks for the kind words! I'll keep it up as long as I can, or until CK does something wacky.

OpenBlueJoe

OpenBlueJoe- Everyone has their own particular duchies/dynasties they like to play. I'll always have a soft spot for the Irish duchies personally. There's something gratifying about bringing the Kingdom of England to it's knees whilst playing the Irish. I've also enjoyed my time in the Motherland playing as the various princes over there and trying to sort out that mess. We'll have to see how the Regency plays out in the end. They've got a long way to go until Zavie takes the reins!

Laur- The Visigoths are certainly important to the history of the area, but for the time being I'm focusing on just getting my independence! Time will tell if the people of Spain will begin to speak Occitan.

And here is the promised Part 2!

Though it's a day late  o

o

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

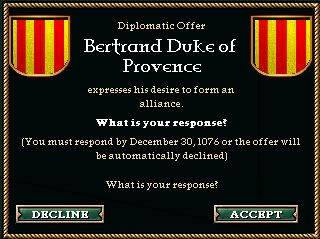

Chapter 2 - Tempore Angustiae - Part 2

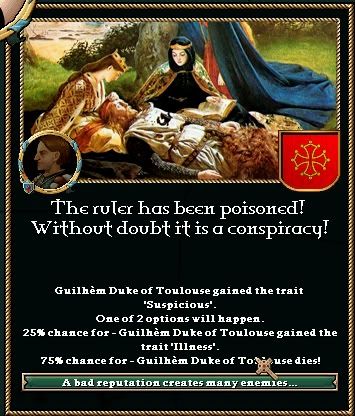

While the assassination of Guilhem de Toulouse and the subsequent institution of a Regency Council rocked the duchy to its very core, the immediate breakup, dissolution, and chaos that was expected to follow didn't seem to materialize. In fact, the remainder of 1071 was marked by a remarkable calm. This is thanks in no small part to the quick action of Raimond de Toulouse. As third in line to inherit the duchy, there was some expectation that Raimond might attempt to bypass his infant nephew to try and seize the throne for himself. In the beginning, some people even whispered quietly that it may have been Raimond himself that was responsible for the former duke's death. In the months that followed the assassination, however, Raimond, and to a lesser extent the rest of the regency council, demonstrated an incredible commitment to staying the course set by Guilhem. Frederi de Noailles made many trips to the Duchy of Aquitaine during 1072, all with seemingly innocent motivations. The truth was revealed, however, in a letter from Gui Guilhem d'Aquitaine, Duke of Aquitaine, to one of his vassals dated August 5, 1072. In it, the Duke of Aquitaine details the plans that he and the Regency Council for Zavie de Toulouse have been formulating with regards to the future of Southern France. The letter makes clear that it is now the intention of both the Duchy of Aquitaine and the Duchy of Toulouse to make every effort to gain their independence from the Capets of Paris.

In addition to the letter, an entry in the journal of Raimond de Toulouse from around the same time period records his happiness at "the glory that our Occitan brethren shall behold." (

la gloire que nos frères occitane verront). Historians have speculated that this might be the first reference made to what would become the "Kingdom of Aquitania" in later years. This self-styled kingdom was intended to incorporate all the Occitan people of Southern France under one banner. This has also led some scholars to conclude that one of the reasons the idea of independence was so appealing to nobles in Southern France was that it was based around a shared culture. To truly understand this, it's necessary to look at the composition of the French people in the 11th century. In the northern portions of the country, as well as the north-central portions, most of the peoples were either Norman or what was generally known at the time as "French", which was really a more generic term for anyone living in France at the time. In truth, even the Occitan peoples could be considered French. Most everyone in France in the 11th century was there as a result of the settlement of the Franks in what was then Gaul back in the 8th and 9th centuries, but dating back to as early as the fall of the Roman Empire. In fact, the divisions between Southern and Northern France can be traced directly to the Roman Empire. During Roman rule, Southern France was known as

Aquitania, while Northern France was known as

Gallia. This seeming division continued throughout the Carolingian Era as the people of Aquitania, or Occitania as it was now called, developed their own language, literature, and art which was separate from the rest of geographical France. In the 11th century, this difference had become even more exacerbated. Nobles in Southern France began to self identify as Occitan instead of French, which caused immediate disunity with Paris and the rest of Northern France. It was this sentiment that scholars believe Raimond de Toulouse and the Regency Council, with the help of the Duchy of Aquitaine, hoped to tap into to help foster their planned rebellion. As early as September of 1072, the Duke of Aquitaine and the Regency Council of Toulouse began issuing directives to their vassals to not deliver tax funds levied by the Parisian Capets to the Royal Crown, but instead to send it directly to their respective liege lords. This led to an increase in the wealth and prestige of both the Duchy of Aquitaine and the Duchy of Toulouse, but the rather blunt message it sent to Paris was not well received.

The call for mobilization has been viewed by some as an attempt by King Phillipe to disarm the rebellious Duchy of Toulouse, at least for awhile.

To say the Capets were angry with the behavior of their nominal vassals to the South was an understatement. Contemporary reports from the court of Phillipe Capet say that when he was informed of the latest happenings in Occitan France, he spewed his mouthful of wine out and ordered the servant to be flogged. This extreme behavior, even by Phillipe's standards, serves as an indication of just how problematic the situation between the North and South was becoming. The Capets, since their ascension to power, had always ruled the other nobles in France by virtue of their larger coffers and larger armies. To be virtually cut off from half of their income was a prospect that would make any Capetian noble begin to pale and search for a solution. To that end, Phillipe Capet did what had always worked in the past, and what he knew best...looked for a fight. It's not entirely clear what the logic was behind Phillipe's decision, but there are two main speculations as to why, in March of 1073, the Kingdom of France joined in the German Civil War on the side of the Emperor. In order to understand the implications of this move, the relationship between Germany and France needs to be fully understood. Ever since the division of Charlemagne's empire into three separate kingdoms, the area that was known as Lotharingia (Lorraine) had been fought over by the German and French peoples. The territory was eventually ceded to Germany in 939 by then King of East Francia, Otto I. The French kings, who are inheritors of the kingdom of West Francia have always been jealous of the territory, and sought to re-incorporate it into their realm. That is why the French involvement in the German civil war is so curious. In the 11th century, the Holy Roman Empire was a patchwork of powerful duchies, quite similar in makeup to France. Unlike France, however, the monarch in the Holy Roman Empire was unable to keep his vassals in line. Beginning almost directly after, and as some historians have said "directly because of", the Norman conquest of England the vassals of the Holy Roman Empire began to break away. The first was the Duchy of Toscana, followed closely by the Duchy of Carinthia. After a lengthy conflict with the reigning Emperor Henrich III Von Franken, both duchies were able to secure their independence. This move, which Henrich seemed to have hoped would preserve his remaining empire only served to embolden the remaining powerful vassals into rebelling themselves. In 1073, almost the entirety of Germany was up in arms against the Emperor, most notably the Duchies of Upper Lorraine, Bavaria, and Swabia.

It was into that quagmire that Phillipe Capet had decided to wade. As was mentioned earlier, there are two potential justifications that seem to make sense when one considers why the French king would want to entangle himself in Imperial politics. The first, and perhaps most simple, is that it would achieve a dual goal by giving the surly nobles of France a common enemy outside their borders that they could focus on. Additionally, it might allow the Kingdom of France to regain part of the long lost Lotharingia that it had ceded to the Germans so long ago. The other justification was a bit more of a gamble, which is one of the reasons that many scholars consider it to be unlikely but, nonetheless, it bears mentioning. Essentially, it can be argued that Phillipe Capet used the war as an excuse to call up the troops of Southern France to go fight in Germany, so that the respective nobles in the South would not be able to raise their troops against him. This rationale is largely discounted due to the fact that it would require Phillipe to assume that already disloyal vassals wouldn't see through the ploy and simply raise their troops at his request. It is known, however, that Phillipe had amassed the troops from his own demense on the borders of Rouergue and Aquitaine. Scholars have speculated that this was an attempt by Phillipe to threaten the Southern nobles into doing his will. This theory is further strengthened by the fact that hardly any of the Northern nobles had their troops similarly called to fight for the King.

Regardless of his motivation however, both the Duchy of Aquitaine and the Duchy of Toulouse agreed to raise their troops for the king. Historians cannot seem to agree on why exactly both duchies, who months earlier were cementing a plot for independence, would easily and willingly hand over their troops to the king. Some speculate that it was Phillipe's troops that caused the traditionally proud and independent Raimond de Toulouse to bend to Phillipe's will. Others say it was merely a ploy by both Aquitaine and Toulouse to gain time to solidify their positions before declaring independence. Whatever the case may be, the events that happened after the deployment of Aquitaine and Toulouse's troops have led many historians to suggest that the identity of Guilhem's killer may not be so secret after all.

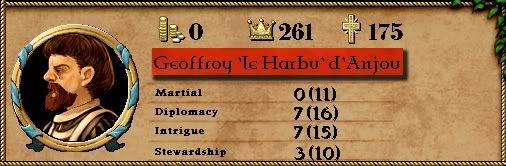

The Count of Foix, Peire-Barnard de Foix, has been shown to be a major royalist sympathizer despite his Occitan heritage.

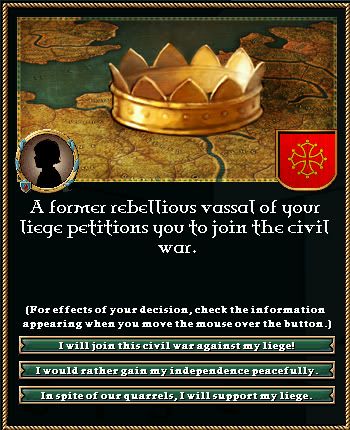

Every since the assassination of Guilhem, the Regency Council had been expending many resources trying to track down those responsible for his death. While no one has been able to conclusively link anyone to the assassination, several signs point to a conspiracy between the Capets and one of Guilhem's vassals. Shortly after one of the King's commanders took command, in association with Marshal Ugues, of the Toulousian troops the Count of Foix, Peire-Barnard de Foix, declared that he would no longer serve an infant or a Regency Council that defied its lawful sovereign. This threw the Regency Council into a panic. Frantically, riders were sent to recall Ugues de Toulouse and his troops to come to the defense of their duchy. Additionally, overtures were sent to the largest landowner in the duchy, Raimond-Barnard Trencaval who was Count of Carcassonne and Montpellier, to raise his troops in the event that Marshal Ugues could not return in time. A week or so later on April 10, 1073, there is a scouting report that showed the Count of Foix had amassed his troops along the border of Toulouse and was making fast progress towards the city. Curiously though, the Count of Foix never crossed the border. Historians have speculated as to the cause of his apparent hesitation, but one dominant theory has arisen to explain it. Historians have speculated that this apparent independent rebellion was actually financed and supported by the Capets in an attempt to cause the Duchy of Toulouse to collapse, or be replaced by the Count of Foix who is now known to have been a staunch supporter of the Capets that had secretly been sending money and messages to Phillipe throughout the majority of 1072 and 1073. Supporters of the "Capet Rebellion" theory point out that the reason Peire-Barnard mostly likely waited at the border was because he was following some sort of plan. The question then becomes, what was he waiting for? A letter from the Capetian commander accompanying the Toulousian troops and Marshal Ugues seems to provide an answer. In the letter, the commander talks about his reluctance to perform his "terrible duties" (devoirs terribles) for the King. He never makes reference to what the duties are, but scholars have speculated that the commander had been ordered to either arrest, or more likely kill, Marshal Ugues at some appointed time. They go on to surmise that he was then to take command of the remaining troops and march back towards Toulouse itself to join up with the Count of Foix's forces. Apparently, however, the commander either became too frightened to actually perform the task, or something prevented him from doing so.

This theory, as its critics would point out, has at least one major flaw. Even if the commander had assassinated or arrested Marshal Ugues, the problem of the troops remained. A large part of them were from Toulouse itself or the surrounding countryside. It seems unlikely, say the critics, that these troops would, first, willingly follow the man that had just killed or arrested their former commander, and, second, that they would then agree to march against their own families. Indeed, while critics of the "Capet Rebellion" theory acknowledge that it would fit nicely into the vast Capetian conspiracy that it was later painted to be, they feel that the true motivation is a much more simply and plausible one given the nature of French politics in the 11th century. In addition to his communications with Phillipe Capet, the Count of Foix also spent the majority of 1072 and early 1073 communicating with his neighbor, the Count of Montpellier and Carcassonne. Surviving letters between the two reveal a mutually held belief that a "change of leadership" was in order within the Duchy. It's speculated that the two Counts hatched a plot whereby the Count of Foix would replace young Zavie and the Regency Council as the ruler of the Duchy of Toulouse. It seems they also had planned to garner royal support for their action by returning the back taxes owed to the Crown. While the plot between Trevencal and de Foix was only hatched in 1072, there is evidence from surviving journals and other sources in Foix that suggest the Count of Foix had grown unhappy with the rule of the de Toulouse family long before he concocted his rebellion. This seems to lend further credence to those that suggest the Count of Foix was responsible, or at least complicit, in the assassination of Guilhem de Toulouse. Regardless of the planning, however, the plan did not play out the way the Count of Foix had hoped.

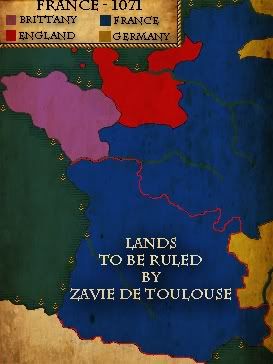

Pictured here is the territory of the Duchy of Toulouse. In red are the supporters of the Regency Council and infant Duke Zavie. In blue is the territory of the Count of Foix. In light blue is the territory of the Count of Carcassonne and Montpellier, Raimond-Barnard Trencavel. Green denotes territory outside the duchy.

Though he had plotted to help the Count of Foix overthrow young Zavie and his Regency Council, Count Trencavel ultimately refused to join either side.

While the Count of Foix waited on the border of Toulouse, presumably for the support of some ally, answers to the cries for help of the Regency Council finally reached the city. Toumas de Gourdon had been dispatched returned from meeting with Raimond-Barnard Trencavel and he finally returned with dire news...the Count would not be raising arms in defense of the Regency Council. Raimond de Toulouse was outraged when he heard the news, and immediately left the city to raise his own troops in Rouergue. Historians have speculated, however, that this was probably the best outcome the Regency could have hoped for, given the known royalist leanings of Count Trencavel. In fact, many credit the bright, young Toumas de Gourdon with convincing Trencavel to abandon his plan for joining with the Count of Foix and instead staying silent on the sidelines of the fight. Historians note that de Gourdon was noted for using the power of the church and fear of eternal damnation to convince otherwise stubborn people that their course of action might want to be re-considered. Scholars point out that this particular method of persuasion would have resonated well with the overly religious Raimond-Barnard Trencavel. Bishop de Gourdon, for his part, never mentioned what exactly took place in his meetings with Count Trencavel, it was reported that the only thing he was willing to say regarding the meeting was that, "God works in mysterious ways." (

Dieu travaille de façon mystérieuse). Whatever the case may be, we do know that Count Trencavel did not raise his troops either for or against the Regency Council. The second messenger that arrived in the city of Toulouse in May 1073 brought happier news. The rider sent to warn Marshal Ugues of the Count of Foix's treachery had arrived in time, and Marshal Ugues had already turned his forces around to meet the new threat. In fact, the rider reported that battle had been joined between the two forces a few days ago and that, when he left, Marshal Ugues had the better of the Count of Foix. This news was received with great joy in a city that had been living under the fear of impending siege for the past few weeks, and it is said that the church bells rang loudly while peasant and noble alike danced in the streets, praising God for the heroic Marshal Ugues. The celebration was short-lived, however, as only days later a messenger arrived with dire news.

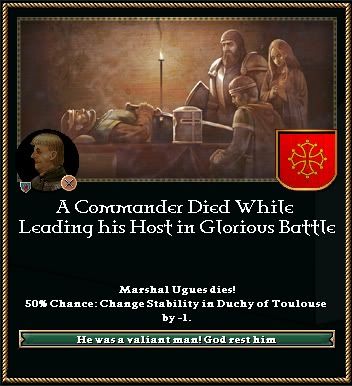

The death of the beloved Marshal Ugues caused much distress and saddness throughout the Duchy of Toulouse.

Details remain scarce as to what actually transpired, but from what detail do remain it seems as though Marshal Ugues fell victim to an ambush. Despite being Marshal for the Duchy of Toulouse, Marshal Ugues was only an average battlefield commander. Contemporary records indicate that while the marshal possessed above average skills as a combatant, his ability to employ advanced tactics and strategies was somewhat lackluster. This is especially important because, while not a tactical genius, the Count of Foix was known to be an above-average commander in the field. According to surviving accounts of the battle, on the third day Marshal Ugues was lured into charging the enemy's left flank, which gave way easily. Without regard for a potential trap, the marshal continued headlong into what ended up being the bulk of de Foix's reserves. The contingent of men that Marshal Ugues was leading, were quickly surrounded and decimated. When news of his death reached Toulouse it was said that Frederi de Noailles, head of the Regency Council in Raimond's absence, ordered the windows of the castle to be covered in black and that all the townspeople wear black for a full week to mourn the passing of Marshal Ugues. It once again seemed as though Toulouse might be facing a potential siege if the forces of Marshal Ugues were not able to continue the fight, absent their commander. As it turns out, however, fortune continued to smile down on Toulouse. Reports dated June 3, 1073, several days after news of Marshal Ugues death had reached the city, indicate that the forces of Gui Guilhem d'Aquitaine and Raimond de Toulouse had reached the battlefield and engaged the forces of the Count of Foix. Raimond de Toulouse, unlike Marshal Ugues, was a renowned military tactician and battlefield commander. It's said that when news of his arrival reached the Count of Foix's camp, some soliders deserted that very night. Raimond fully lived up to his reputation over the course of the next two days as the battle once again raged. At its conclusion, the entirety of the Count of Foix's forces were either captured or dead at the hands of the now revenge-minded Toulousians.

Raimond de Toulouse's victory over the Count of Foix's forces was a total one.

The castle of the County of Foix was an impressive structure, but cutoff from supplies it was a deathtrap to the few defenders that remained.

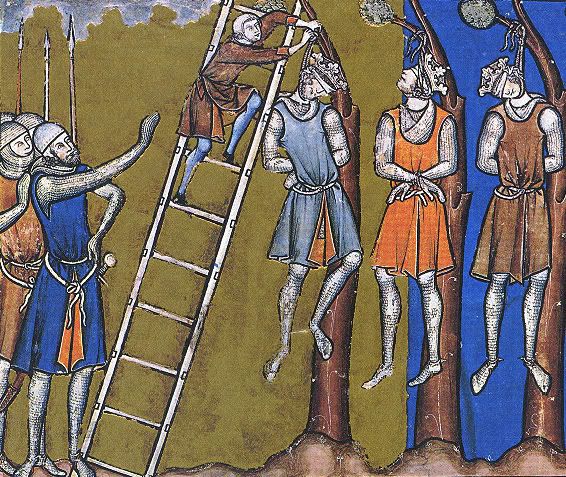

Raimond de Toulouse wasted no time in laying siege to the Count of Foix's castle, which, thanks to the battle the previous day was guarded by a skeleton garrison. Nonetheless, the Count of Foix succeeded in holding off the attackers with his men for over a month before, on July 24, 1073, he was taken prisoner by his own men who had been cut off from supplies for almost a month. Sources from the soldiers of the Toulousian army record that the Count was dragged from the castle kicking and screaming in his bed clothes, all the while cursing his men as traitors and cowards. The other, and perhaps more truthful account, recorded by Toumas de Gourdon, who had stayed with the besieging army, was that the Count of Foix was taken into the camp with all the dignities one could hope for a man of his station, and that he was treated with the utmost respect. But however much respect he was treated with during the surrender did not translate to his death. It was the custom, and to some degree the right, of noblemen in 11th century France to be granted death by beheading, which was considered more dignified than the traditional death by hanging used for criminals from the lower and middle classes. A surviving account from a soldier who witnessed the events tells us how Peire-Barnard de Foix, Count of Foix, met his end:

The traitor [Peire-Barnard de Foix] was brought to us by his soldiers on the morning of the 24th. He was met by the commanders in their tent, and then led to the center of camp where he was disrobed and beaten soundly with canes and sticks by the men there assembled. Throughout it all, he was able to hold his tongue. It wasn't until the Count [Raimond de Toulouse] ordered him stretched* that we heard his first cries for mercy and death. After that, a crown made by one of the camp blacksmiths was brought to him and affixed to his head by way of metal barbs which hooked the traitor's skin. He and his advisors were then dragged to the castle where they were hung with rope made from their own banners.

(Le traître a été porté à nous par ses soldats, dans la matinée du 24. Il a été accueilli par les commandants dans leur tente, et ensuite dirigée vers le centre du camp, où il a été déshabillé et battu à bon escient avec des cannes et bâtons par les hommes réunis là. Pendant tout ce temps, il a pu tenir sa langue. Il a fallu attendre le comte lui a ordonné étiré * que nous avons entendu ses premiers cris de miséricorde et de la mort. Après cela, une couronne faite par l'un des forgerons camp a été amené à lui et apposée sur sa tête par voie de barbes de métal qui accro peau du traître. Lui et ses conseillers ont ensuite traîné vers le château où ils ont été suspendus à la corde faite de leurs propres bannières.)

*Stretching was another name for the practice of attaching a rope to each of a person's limbs and pulling them in separate directions either with horses or a team of men.

This is a medieval artist's depiction of the execution of the Count of Foix. It should be noted that the vaunted "traitor's crown" was only worn by the Count of Foix (depicted in the middle) and was styled after the Capetian royal crown. Additionally, the men executed were hung from the parapets of Foix Castle, not from trees.

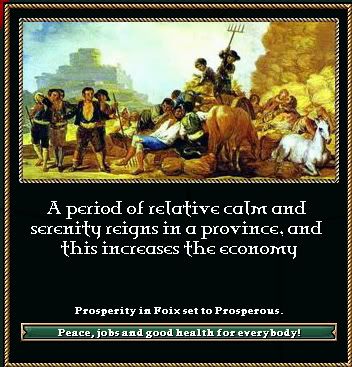

Shortly after the Count of Foix's execution on July 25, 1073, the young Zavie de Toulouse was formally invested by Toumas de Gourdon as the new Count of Foix. Some contemporary records show that the execution of the Count and the seizure of his lands in the name of Zavie by the Regency Council caused the other vassals to voice some complaints. None of these grew into any serious threat at the time, however, as the lesson taught to the Count of Foix served as a warning to the enemies of Toulouse both near and far that dissension would not be tolerated. The years of 1071, 1072, and 1073 proved to be a trying time for the Regency Council, but, for the time being it appeared as though they were once again the well-settled masters of the Duchy of Toulouse.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alright, there's the second part of Chapter 2 finished! I apologize for the brief delay in getting this posted, but I hope it was worth the wait. I plan to do a brief interlude covering the reign for Guilhem de Toulouse before I post the next full update. Comments, questions, and feedback always appreciated!