Chapter 9: Preparations for a new war

17 February 1456, the Chancellor's office

Sextus Porcius Cato, Duke of Pisa, was in intense discussions with the current interim Chancellor of the Tuscan Empire, Marcus Tullius Cicero, Duke of Romagna. Sextus had developed a plan to try to Integrate Naples into the Empire more rapidly; by sending periodic bribes to key Neapolitan nobles, they would eventually allow an outright annexation of Naples. The only other notable event was Austria's war on Serbia. Although Austria took no land, they did force Serbia to isolate herself from the international community and pay a small indemnity.

That wasn't what the discussion was about, though. The Doge of Venice, apparently angry with Tuscany, had arranged to have the Pope excommunicate the Empire.

"Chancellor, this is serious. This could cause internal disorder as well as give any ambitious nation the right to attack us!"

Cicero briefly considered the situation. "I would say you're right, Sextus. We have two options; first, we can improve relations with the Pope. Second, we can improve relations with Venice and hope they see fit to lift the excommunication."

Sextus pondered. "I do not think the Emperor would approve of the first option. We've had a very strict policy of no relations with the Pope since Leo I's statue against him. Surely we could appeal to the Venetian love of money?"

Cicero smiled. "An excellent solution to our predicament, Sextus. It would seem you will be a good successor when the time comes. We will petition the Venetians to re-enter their trade league, and send periodic cash shipments to them."

Sextus nodded, and prepared the request to be forwarded. He also quietly continued to send small shipments to Naples -- the addition of new territory would help Tuscany in any wars that could result from the excommunication.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

4 January, 1457, the Imperial Throne Room

Sextus was preparing to give his first official report as the new Chancellor. Cicero's retirement party a few days earlier had been extremely lavish and tasteful. While he thought such expenses were a silly waste of capital, Sextus had to admit he'd had a good time. He'd even met a girl there -- although nothing was serious yet, she appeared to be quite prudently invested, an important facet in any marriage. He'd sent a formal request to her father, as was the proper thing to do.

He carefully perused his small pouch of documents. Everything was in order, just the way it ought to be. He entered the Imperial Throne Room.

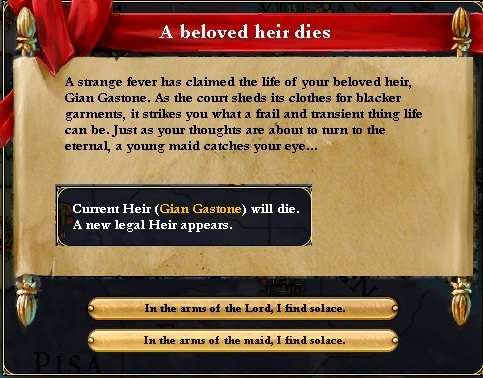

Prince Gian greeted him with a rather sloppy salute. He was hardly ever in the capital, as he showed a greater appreciation for the treasures of Rome than he ever did for leadership. Gian was particularly fond of plays, hardly a suitable occupation for any noble, let alone the heir to the throne. Privately, Sextus thought that another heir ought to be designated, but the Empress proved to be incapable of producing children. He shook his head in disgust when he was sure no one was looking.

"Your Imperial Majesty, I have today's report ready for you."

"Thank you, Sextus. Continue."

"Emperor, I've compiled a new overview of the nobility.

Gian Gastone Datti, Prince of the Empire and Duke of Rome

Marcus Tullius Cicero, Duke of Romagna

Agrippa Tullius Cicero, Duke of Ancona

Sextus Porcius Cato, Duke of Pisa

General Gian Gastone del Moro, Duke of Sicily

"We still have no new Duke of Siena -- for now, the Dowager Empress can handle affairs, but she has repeatedly sent messages through my office to ask you to appoint one." He looked expectantly at the Emperor.

The Emperor sighed. It was at times like this that he missed Cicero. The new chancellor had proven to be an effective diplomat and administrator, but showed almost no initiative. It wasn't a lack of ability or intelligence, but merely what he considered 'proper.' He never questioned an Imperial decision; of course, Julius liked loyalty, but without at least some resistance he feared that he might lose sight of the important matters. Julius asked Sextus directly for advice -- Sextus merely deferred the question, responding "I could not possibly offer any substantive options -- I am too new in my office."

Julius hoped it would get better, but for the meantime, he merely waved the issue off and asked Sextus to continue.

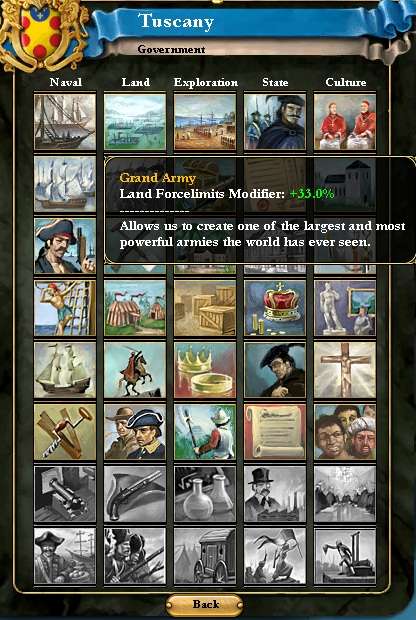

"Very well, my Emperor. We've begun raising additional forces to start a second Legion of 9,000 men while we simultaneously expand the navy. Surprisingly, nobody has taken advantage of Venice's decision thus far; still, I think you are wise to continue preparing for a potential war. Italy is quiet right now -- Savoy has recently started a war with Sardinia, but this should not be a big distraction. Lastly, on your order, I have hired a team to build a Constable in Palermo; maximizing Sicily's wealth will be a welcome boost to our economy. That is the end of my report. Was anything unclear?"

The Emperor shook his head and dismissed Sextus, who executed a very stiff bow, backed away, turned, and left. Julius I made a mental note to ask Cicero to speak to Sextus; the boy was much too rigid and tactful, nothing like his father had been. For a moment, he thought of his old friend, the late Marcus Porcius Cato Minor. He missed him almost as much as he missed his father.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

13 February 1457, the city of Leipzig, Saxony

Agrippa Tullius Cicero was irritated. Why was he in this backwater little town, instead of at home in Ancona, where he belonged? He suspected his father had something to do with this; while the elder Cicero was no longer Chancellor, he still kept in very close touch with the new Chancellor Cato and the Emperor. He had doubtless heard of Agrippa's... indiscretions with Leopold VIII's daughter, and since Emperor Julius had begun considering trying to make himself the true Holy Roman Emperor again, Saxony needed to vote for Tuscany.

Saxony was interested in voting for Burgundy -- even with the very best relations, Tuscany was considered far too infamous to be a legitimate candidate at this time. It would take some time before this could be changed. He still couldn't leave, though. Sextus had formally demanded that Agrippa actually speak to the Elector of Saxony and prepare a detailed report! Agrippa liked the beer and bratwurst, but German women were just too thick for his tastes. Not like Italian women, or even that little vixen from Austria...

He snapped out of his little daydream, sighed again, and rode to the palace in Saxony. Might as well get this trip over with...

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

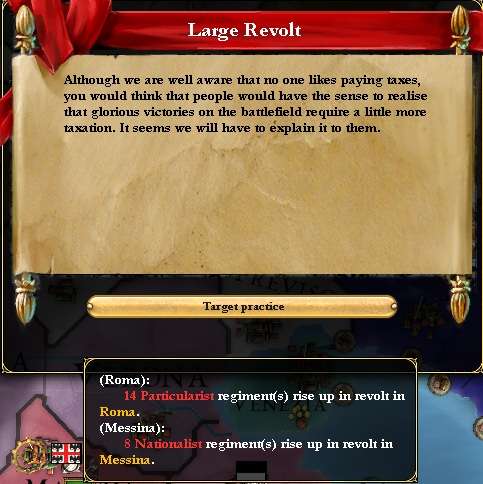

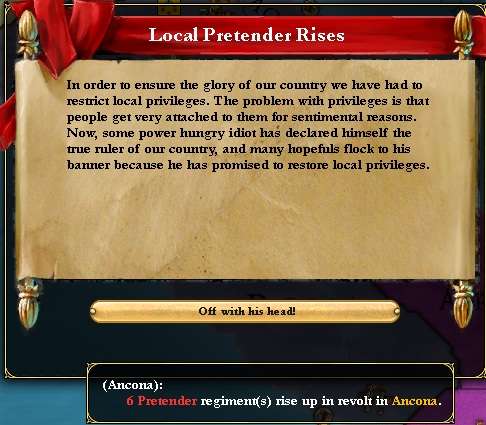

18 September, 1457, Messina, Sicily, outside the camp of Legio II 'Sicilia'

General del Moro mopped his brow. He'd hoped becoming Duke of Sicily would mean the good life for a while. Instead, almost constant revolts in both Palermo and Messina demanded his attention. He'd even had to call for assistance from the Emperor's Legion, which currently was under the command of one of his younger sons, Bartolomeo. Although he did not officially rate the title of "General," Gian Gastone trusted his son implicitly, and planned to leave his Duchy to his son one day. He'd thought placing his loyal son in command of the First Legion -- the one most likely to see combat -- would free him to retire, unofficially. Instead, it was his son with nothing to do.

Achille d'Agnesi was the Sicilian traitor that was trying to make his Duchy disappear. The General had already won multiple battles against him, but they were almost always bloodier for him than for the Sicilian, who knew the land very well. The General had over a dozen wounds from this campaign alone -- more than he'd had the entire war to take Sicily in the first place.

While he rested after the latest bloodbath, he took a look at the diplomatic dispatches. He liked this new kid in the Chancellor's office, Sextus Cato. His dad was a hero to every Italian soldier; Sextus wrote very crisp and neat reports, easy for even an old soldier to read. This one was only one sentence long.

While Milan and Savoy remain at war over Sardinia, Aquelia has sneakily invaded and captured Sardinia for herself.

del Moro had to admire that. It was exactly what he would have done. Now, Milan and Savoy were fighting over a prize neither one could ever have, because Aquelia, ostensibly Savoy's ally, betrayed Savoy and scooped it up. He chuckled.

A few months back, a specialist hired by the University of Rome taught he and his troops some new marksmanship techniques. del Moro always enjoyed learning new methods of fighting, even if they did not make as big an impact as he would have liked. Still, compared to the rest of the world, the 7th Manual of the Army (often called "Land 7" for short) made Tuscany a leader in military thought.

He had one final bit of paperwork; an expense report for the army. This did not make him laugh. The Master of the Imperial Mint, Count Giuliano Chigi, had been unable to pay off the Imperial debt from the last war, and had asked all departments to scrimp and save. At least he didn't have any budget cutbacks, but he wanted to buy some new swords for some of his men. For now, though, it wasn't in the budget. These Sicilian swords were pretty nice -- perhaps he could capture some.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

24 January 1460, the Chancellor's office

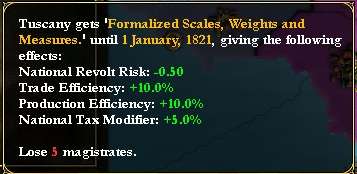

Sextus finished carefully archiving his reports from the past few years. He was still stunned that his father had no detailed record keeping! The grateful Emperor Julius I had authorized a large expenditure to not only establish such a system, but sent five of his most capable Magistrates to assist Sextus in creating a new system of Weights and Measures that would surely benefit the Empire greatly.

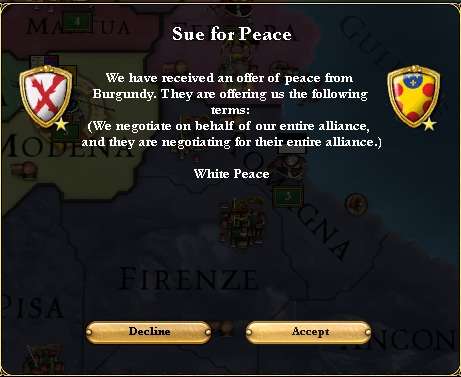

Sextus thumbed through some of the foreign affairs telegrams. The war between Savoy and Milan ended very badly for Milan -- although Milan had not lost land, they were diplomatically isolated. Aquelia had also punished Ferrara, with the help of Burgundy, and created the newly independent Modena. Austria was now Defender of the Roman Catholic Faith.

The only other major event of the last few years was a new education program in Siena. Recognizing that territory inside the Damned German Empire was often carefully guarded, and fearing an ultimatum,the Emperor had moved the National Focus to Siena to Promote Cultural Unity. It seemed to work, although this meant reduced revenues and no army construction for a short time in Siena.

He sat down to prepare a detailed report on the new Weights and Measures system; he knew the Emperor appreciated specific and accurate statistics and depended on them to make a decision.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2 January 1461, the Imperial Throne Room

Emperor Julius I was getting tired of funerals. 1460 had been such a productive year -- Messina received a Constable and the world was otherwise peaceful. His excommunication had not been lifted -- Cologne now controlled the Papacy -- but he would rather rot in purgatory than even consider apologizing to the Pope. He began to realize how corrupt the Pope was; perhaps the entire Catholic System needed some serious reform? This thought struck him powerfully. After a quite moment of reflection, he returned to the day's earlier events.

Two nobles had been buried that day -- Duke Gian Gastone del Moro, General of the Empire, and Count Vitale Buti, Imperial Tax Collector. The General had died from repressing yet another revolt.

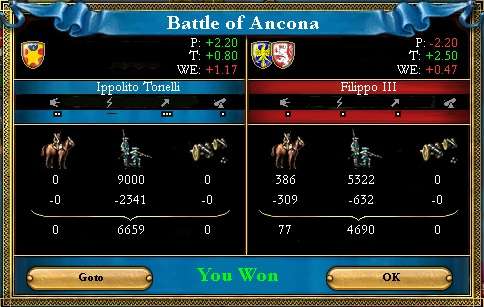

The Emperor was confident he could Centralize control no further. Bartolomeo del Moro succeeded his father as Duke of Sicily, but had requested that another General be hired -- Bartolomeo was still quite young, 22 years of age, and many felt it was improper for such an inexperienced fighter to be a general. He hired the late General's second in command, Ippolito Tonelli. A capable leader, he could move his troops with speed, conduct sieges, and was particularly skilled in training his archers. His only shortcoming was a lack of appreciation for the shock tactics of cavalry. Nonetheless, General Tonelli would be a fine substitute.

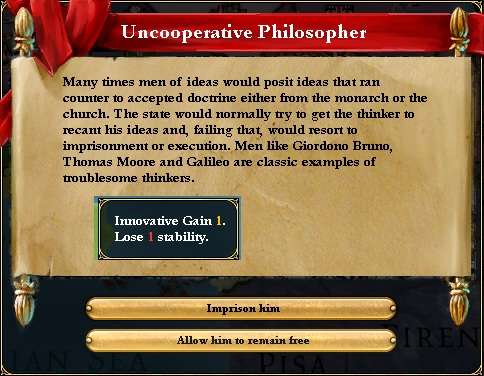

Valeri Buti, as Tax Collector, was extremely unpopular. It was something of a relief when it turned out he hadn't been assassinated; rather, he'd eaten some very bad pork, the result of an insistence that he only eat raw food. He contracted a very nasty disease and died shortly thereafter. Buti's replacement, a brilliant Philosopher named Bonaventura Bizzelli, was, in some circles, considered even brighter than Constantine.

The Emperor simply didn't like Bizzelli as well, though. He wasted his time on useless metaphysics and silly theological conundrums. Although the rest of Europe fawned over his logic and reason, the Emperor privately thought him an idiot blowhard who hid his actual faults by using cumbrous and dense language. Still, his prestige and credibility was useful.

Thinking of Constantine reminded him of his Chancellor, Sextus Cato. Julius had come to appreciate Sextus's eye for detail and voluminous knowledge of every arcane law in the Empire. He was very shrewd, but never presumed to step out of turn. He'd even been willing to offer criticism recently, but only in the most respectful manner. For his faithful service, Sextus had been awarded the Duchy of Siena; young Cato now had two Duchies, the only man in the Empire who could say that.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

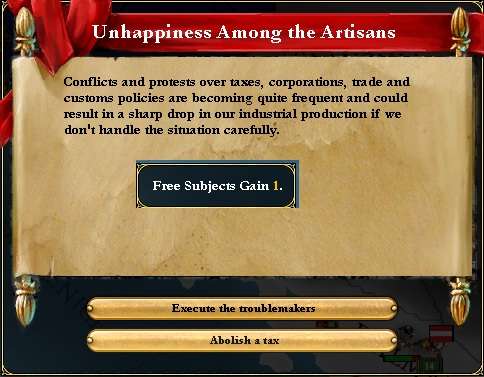

15 March 1462, a gathering of artisans in Rome

Publius Porcius Cato, the younger brother of the Chancellor, had renounced public life to become a blacksmith. He thought only manual labor was honest labor, and his goods were prized throughout Europe. The nobles were particularly pleased with his work; it was refreshing to buy from a fellow noble (Publius was a Baron; Sextus had offered him the family Duchy of Pisa when he got the Duchy of Siena but Publius turned him down) and who was far more educated than the average blacksmith.

Just when he thought he could completely escape public life, however, a group of his fellow artisans had asked him to serve as their voice and present a petition to the Emperor. There was a lot of complaints about the high taxes on artisans recently; they couldn't even sell their businesses without the permission of the local Baron! Publius had agreed to serve as their representative, and was now waiting in the Imperial antechamber for an audience.

The first official to see him was Sextus. "Brother, what brings you to the capital? You have no official reports to present for many months now."

Publius explained his petition (privately annoyed that the only legitimate reason his brother could come up with was for a report) as Sextus frowned. "Brother, I must advise against this. As a Baron, you certainly have the right to request an audience, and I will see it is granted, but the Emperor has been particularly irritated with the Prince recently and may be in a foul mood. You might get executed."

Before Publius could register any surprise about his brother's concern, Sextus continued, "Of course, that could cause considerable harm to our family's reputation."

That seemed more like Sextus. Publius knew his brother loved him, and he loved his brother, but Sextus refused to show any emotions in public. It just wasn't proper. Publius insisted on seeing the Emperor, Sextus nodded, and showed him in.

The Emperor was indeed in a foul mood. Prince Gian had finally gotten it into his head that he could be an Emperor himself -- and he promptly disappeared, ostensibly on Imperial business in Constantinople. It had been three weeks since he had any word of his son, so Julius I was not particularly pleased to see Publius.

"Publius, your brother tells me you have a concern you need to bring to my attention?"

Publius took a deep breath. "Your Imperial Majesty, the artisans in the Empire are tired of the arbitrary taxes some of your less scrupulous nobles have been charging. In particular, a tax on salt instituted by the late Count Buti is still on the books; the Master of Mint Count Chigi insists it continue until the Imperial debt is paid off."

"Baron Cato, the Master of the Imperial Mint is well within his authority to approve or repeal taxes as he sees fit; I happen to agree that we do need to pay off this debt to relieve the burden of interest on the Imperial treasury."

Publius swallowed, hard. He knew if he pushed too hard, he could very well end up with his head on the chopping block, and that his brother would even sign the death warrant. "Emperor, the artisans do not object to doing their patriotic duty and paying their taxes. What they object to is an unauthorized tax that appears solely to enrich the recently departed."

The Emperor was startled. He asked Sextus to check the records; within three minutes, Sextus had returned and presented a report. "Emperor, I fear my brother is right. Although the tax is officially part of the code, Count Buti simply changed the numbers on his revenue reports without actually providing this revenue; he always evaded any attempts to investigate, calling it his noble prerogative to hold funds until you requested them. I regret I had not caught this sooner, Emperor, as we could have saved much trouble."

Julius I considered the new evidence, and with a stroke of his pen, abolished the tax.

"Publius, you have done your fellow artisans a great service. Are you certain I cannot persuade you to join your brother in government service?"

Publius shook his head, ruefully. "Unfortunately not, My Emperor. My clients would be greatly displeased, and my apprentices are already overworked. I would only ask that you consider relying on my foundry to supply any future needs you might have in the future."

The Emperor nodded. "I will do that, Baron Cato. Thank you again for bringing this to my attention; have a pleasant evening."

Publius bowed, shook his brother's hand, and left for Pisa. When Sextus had gone on and on about Imperial justice, Publius had thought his brother just an over-enthusiastic employee; he had to admit to himself that he was wrong.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

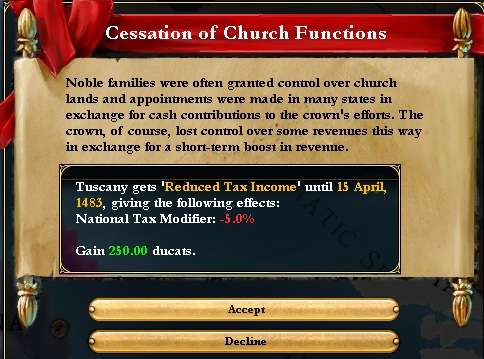

15 April 1463, the office of the Master of the Mint, Guliano Chigi

Count Chigi, an extremely excitable man, was even more excited this day. He'd paid of the debt a few days earlier, and was now told he would get a big influx of currency from some kind of church-political nonsense.

A couple of months ago, he'd authorized the construction of some marketplaces. With another 250 ducats, the navy and army could be even further expanded than they were now! Some Carracks could be a useful addition; he could even redistribute revenues to new technical research.

Count Chigi was trembling as he signed the order -- how could life possibly get any better?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

6 February 1464, the Chancellor's office

The Chancellor sighed and shook his head. Chigi was getting a little too hyperactive again. He could barely read the purchase order, but thankfully he'd already spoken with the technicians at the University of Florence's business school. They'd recently provided him with some plans for a new Workshop; five were immediately ordered, thanks to the surplus from the Emperor's decision to collect the money from the Church lands immediately as one lump sum.

He did have one concern though; his agents informed him that Ragusa was on the verge of collapse. As a vassal of Tuscany, the King of Ragusa had pleaded for funds, but the Emperor had declined, saying that Tuscan imperial funds were for Tuscans only.

Sextus privately thought that the Emperor thought the arrangement was more trouble than it was worth; he would probably abandon his stewardship over Ragusa at the first opportunity. Sextus admitted this was probably a sound move.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

15 June 1466, the Imperial Throne Room

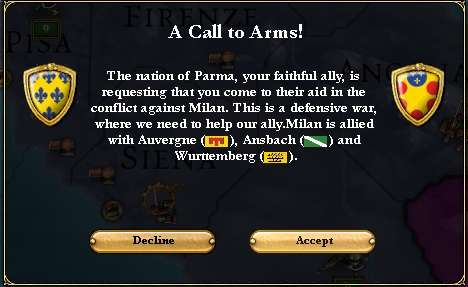

The Emperor was pacing back and forth. 1465 had been a banner year for academic accomplishment -- Trade Depots and Training Fields were invented by some clever scholars, and while none had been built, the Emperor knew that new technologies were always valuable,even if sometimes it was indirectly so. However, a series of unexpected diplomatic moves by Austria had created an unusual opportunity.

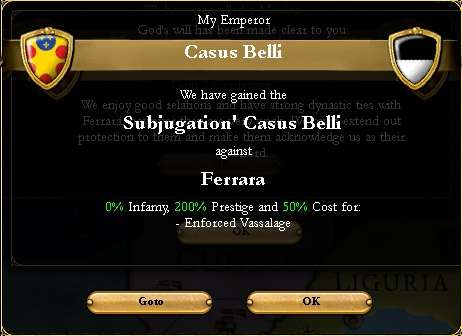

Two months ago, Agrippa Tullius Cicero, still grumbling about his "interment" in Saxony, had reported that the heir of the Elector of Saxony had died in a freak hunting accident. He'd asked if the Emperor wished to press a claim of his own. However, before the Emperor could respond, a second more urgent letter notified him that Austria had already done so, and that the Emperor of Austria was also the Elector of Saxony now. Fuming, he'd thrown away his plans to convince an elector to vote for him yet again. That's when he had an idea -- perhaps the Emperor would look the other way if he tried to subjugate Ferrara?

A forged document, prepared by the court Philosopher, Bezzini

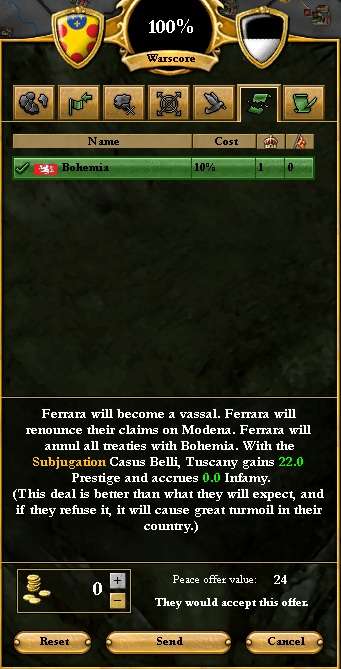

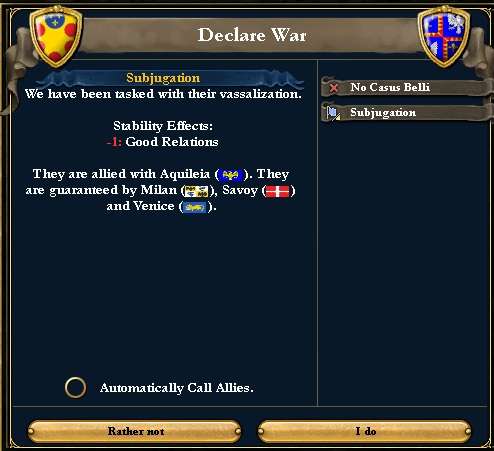

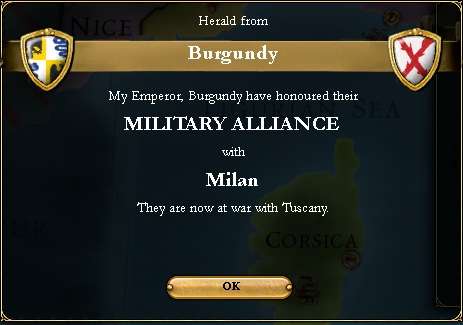

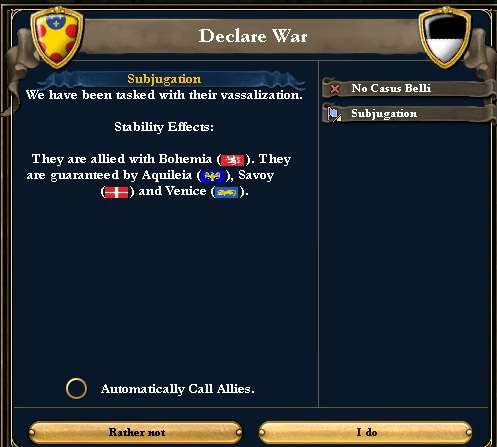

With this semi-legal casus belli (the Chancellor did not dream of contradicting the Emperor), the Emperor ordered Sextus to prepare an official declaration of war and deliver it to Ferrara personally. Sextus was busily at work, so the Emperor had time to consider this. Bohemia was allied directly to Ferrara; Savoy, Aquelia, and Venice had all guaranteed it's independence.

Still, by vassalizing Ferrara, they would not be "unlawfully" claiming territory and thus the Emperor could not intervene before or after the surely quick and successful war, a powerful motivation to declare war. After a few more minutes, the Chancellor entered the room, showed the declaration to the Emperor, who signed it, and Sextus set out for Ferrara.

War had come again to the Empire of Tuscany, and this deceptively minor war would bloom out of control.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

That's the end of Chapter 9. I've officially decided to break Chapter 10 into two parts; I will try to have the first part done by this weekend.

I'm going to make a silly mistake with Naples in the next update or two -- if anybody guess what that mistake is (it's vaguely hinted in this update), they can create a character, as our friend Michaelangelo had in the past. Who knows? Maybe they'll also become Chancellor and die a few years later!