News from Nowhere

VII

“Experience teaches us that it is much easier to prevent an enemy from posting themselves than it is to dislodge them after they have got possession”

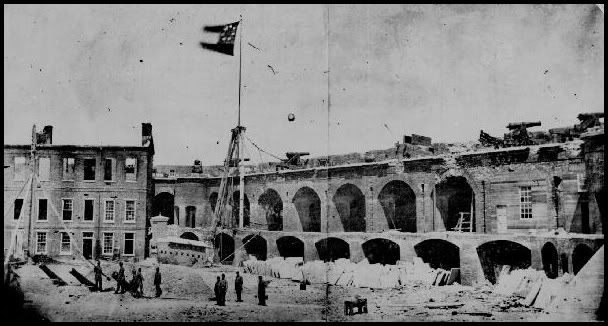

Marines at Siboney

On 4th June 1871, marines from the CSS Robert E. Lee led the preliminary landings onto Cuban soil, just outside the village of Siboney. The light-defended beaches had been prepared with naval fire and by the 6th, the entirety of V Corps was ashore, with only minor casualties. President Seddon telegrammed the marine commander, Captain Arthur McKee, congratulating him on a job well done. Such was the story presented in the Confederate papers. Little did the public know of the crucial aid provided by the Cuban guerrillas. On the 4th, 3,000 partisans, led by Maximo Gomez had engaged Admiral Negra’s land forces in a major diversionary attack outside Santiago, the capital of Oriente province. Despite years of combat experience, the Cubans were ill-equipped for conventional warfare. As such, their assistance to the Confederate landings cost them almost 500 dead and wounded in the face of fortified positions. On the 6th, General Braxton Bragg arrived outside of Santiago with his forces, including much needed artillery. Soon from both land and sea, the Confederates pounded Negra’s positions. On the 9th, Bragg offered terms, but the Admiral refused. Realising the port was vital to supplying the invasion, and aware of the need for a speedy campaign, Bragg ordered a full assault. The next day, the 1st Virginian and 3rd Georgian Brigades made their attack, with Gomez’s Cubans acting as skirmishers. As the advance began, Confederate officers mocked the cover and concealment tactics the partisans used, as they cautiously made their way through the long grass and hedgerows. As the infantry came within range of the Spanish rifles, the mocking promptly ceased.

At 1500 yards, the Spanish, hidden behind fortifications and inside makeshift redoubts, revealed themselves and unleashed a savage barrage of rifle fire, cutting down the neatly presented Confederate soldiers. The solid ranks proved easy targets, and if not for the order to advance at speed from an ageing Colonel Pickett, the attack might have been lost within minutes[1]. Although both sides were newly-armed with breech-loading rifles, the Confederates struggled to match their opponents for firepower. Outside of the senior officers and NCOs, V Corps comprised overwhelmingly of untried soldiers, with only childhood memories of the Secession. Meanwhile amongst the veterans, the neo-Napoleonic tactics of volley fire and solid lines were still seen as the most efficient battle winning tactics. As such no-one on the Confederate side was prepared for the ‘Cuban’ style of warfare. Arguably only Bragg’s use of his artillery advantage won the day, as the Spanish left flank crumbled under concentrated fire, allowing the Georgians to enter the town in the early afternoon. Aware defeat loomed, Negra laid down his arms. However not before ordering the remnants of his naval squadron to scuttle in the harbour. This not only denied the Confederates the warships themselves, but made the port of Santiago all but useless to Bragg’s campaign for the foreseeable future. A poor prize indeed for the almost 2,000 casualties inflicted on the allied forces in less than a week.

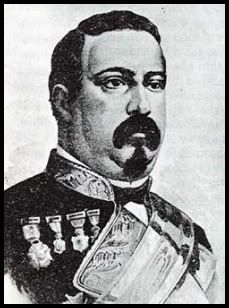

The Butcher of Bayamo, General Blas Villate

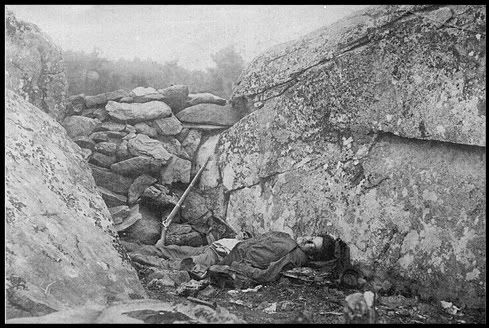

The Siege of Camaguey was a brutal meat grinder, evocative of the trench warfare seen at Washington and Wheeling during the Secession. For nine days, Bragg’s forces slowly hammered against the walls and barricades of Villate’s bastion. The heavy guns that had proven so vital at Santiago proved difficult to position in the muddy slopes around Camaguey, while the naval support was now unusable so far inland. As such fighting came down to traditional charges across, open and difficult ground. The 3rd Virginian Brigade were almost annihilated in one such charge on the fourth day, as they broke through the outer defences only to find themselves ambushed in the tight city streets. Over a third of the Spanish defenders were Cuban-born members of the fanatical Volunteer Force. Born to upper and middle-class families of peninsular stock, these young paramilitaries were the shock troops of colonial repression in Cuba, driven by personal and ideological incentive to smash the revolutionaries. Despite lacking in the discipline and experience of the regular forces, the Volunteers were fierce opponents. On the 10th, Bragg threw his entire army at Villate. This included the dismounted cavalry of Forrest’s Brigade, who charged with sabre and pistol up the slope towards the Spanish. Finally the demoralised regulars fell back, while many surrendered to the Confederates, fearful of guerrilla retribution.

Dead soldier of the 3rd Virginian - 4th July 1871

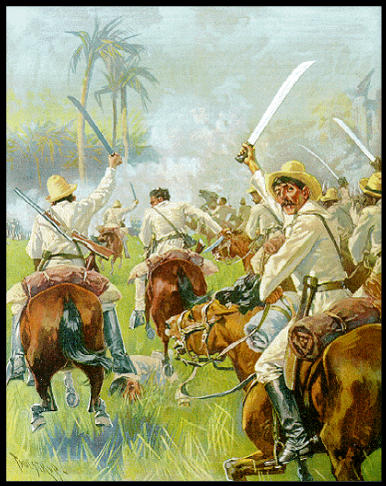

Camaguey was to be the bloody high-mark of the land war in Cuba. Campos had gotten word of Spanish forces building in Puerto Rico and decided on a multi-layered defence, to spare Havana the violence of early July. On 19th July, Forrest’s Tennessee horsemen, acting as Bragg’s vanguard, engaged the hussars of the elite Pavia Brigade outside the town of Sancti Spiritus in a mass cavalry battle unseen since the Crimean War. After several hours of charges and manoeuvre across the open grasslands, the hussars retreated. The Pavia Brigade would launch another attack on the Confederate forces two day later, however it was only a fleeting skirmish. General Campos was busy preparing defences throughout the loyalist western provinces and was keen to delay Bragg’s advance. On August 1st, the Confederates secured control of Santa Clara province after a week of mobile combat against the Pavia Brigade and several infantry regiments. Although the conclusion was never in doubt, the canny Spaniards made extensive use of guerrilla tactics. Time and again Bragg’s column were ambushed and pinned down by devastating rifle fire and light artillery. Another 1,300 men were killed or wounded, while the Spanish withdrew in good order, having suffered only a tenth as many casualties[3]. Despite these setbacks, by early August, the Army of the Antilles were approaching Havana and its impressive defences. On the 5th however, attention turned to the home front. The Spanish had struck Charleston.

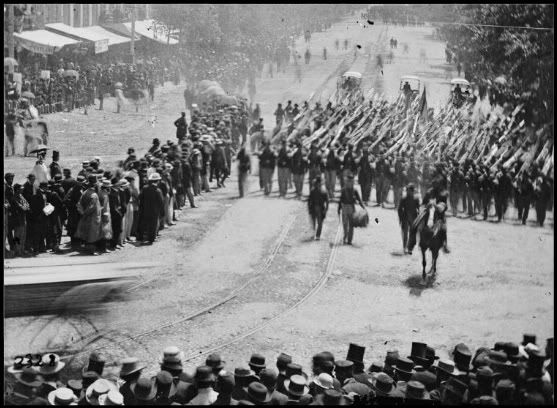

Charge of the guerrillas

[1] Pickett finally gets his glorious charge ITTL. Its hardly an easy victory, but he certainly wont have the horrors of Gettysburg on his conscience.

[2] All of this is in tune with how the Cubans got treated in the U.S during the Spanish-American War. There’s hundreds of articles portraying the guerrillas as little more than thieves, profiting off of the chaos of the American liberation (ignoring the decades of insurrection) to loot and gain position. This is despite overwhelming primary sources from U.S troops praising the Cubans as hard-working, brave and excellent fighters. The infamous yellow journalism worked both ways it seems.

[3] These lop-ended results are mainly down to my poor tactical skills and impatience. Also I focused on economic techs over military post-Secession. Meanwhile in terms of leadership and organisation Spain is way ahead of me. Add to that heavily dug-in forces and fortifications in hilly terrain and you see what happens.

Last edited: